Getting into Gear for 2014: Shifting New Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies into Drive

Connecting People to Coverage through Streamlined Enrollment Processes

The ACA envisions seamless and timely access to the continuum of coverage options regardless of where or how someone applies. To achieve these objectives, the ACA establishes new expectations for simplifying the application process, coordinating enrollment, and moving toward paperless verification of eligibility. Many of these changes accelerate successful state strategies in harnessing technology to make the process work better for both individuals and state agencies.

Applying for Coverage

The ACA requires Medicaid, CHIP, and the new health insurance Marketplaces to adopt a single, streamlined application that screens eligibility for all coverage options. To this end, HHS created a consumer-tested model application, which states can customize to better fit their programs. For example, states can substitute state agency names, logos, and phone numbers. States can also eliminate questions that aren’t applicable, such as how long a child has been uninsured in a state that does not impose a waiting period in CHIP. Alternatively, states may develop their own single, streamlined application, subject to HHS approval. However, alternative applications may only include questions relevant to the eligibility and administration of all of the insurance affordability programs, and only for individuals who are applying for coverage.

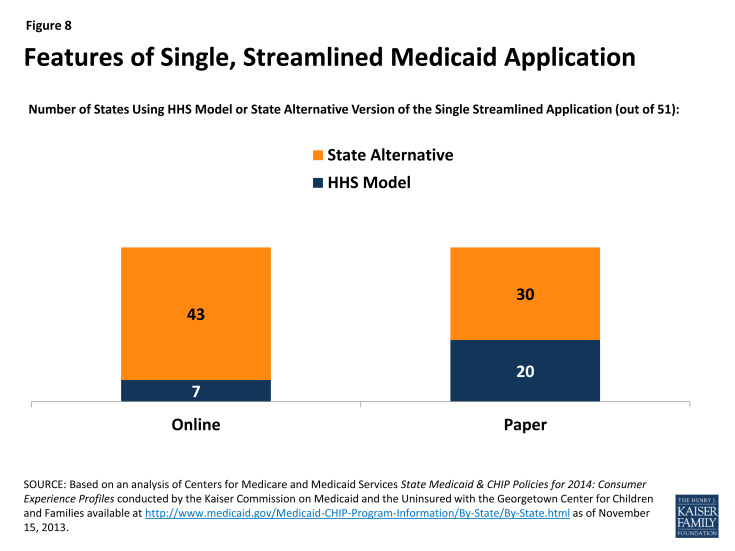

Most states (43) will use a state alternative online application, while seven (7) will adopt the HHS model online application. Fewer states (30) are using or plan to use a state alternative for their paper application (Figure 8). In 32 of the states using an alternative application, the version that is initially available will need further revisions to fully comply with the ACA standards, for example, by removing questions that are not relevant to eligibility. Notably, in 15 states, multi-benefit applications are available that allow individuals to simultaneously apply for health coverage and other benefits such as food or childcare assistance. Like the alternative application, a multi-benefit application must ask the relevant questions for all health insurance affordability programs. It must also clearly indicate which questions are optional for determining eligibility for health insurance coverage only.

State Medicaid agencies are required to make the single streamlined application available through multiple modes, including online, by phone, and on paper by January 1, 2014. As of October 1, 2013, 43 of 50 reporting states have deployed a single, streamlined application through their Medicaid agency, with 43 state Medicaid agencies having a paper version in place and 36 having launched an online version. The seven (7) remaining reporting states are in the process of developing their single, streamlined applications with nearly all anticipating completion by January 1, 2014 (Appendix Table 4). In the interim, these states are continuing to utilize their existing Medicaid applications and individuals who may be eligible for premium tax credits are being directed to apply through the federal Marketplace.1 Looking ahead states will continue work to make the single streamlined application available through all required modes, although some state agencies may not have all of these avenues available until later in 2014. In these cases, CMS is working with states to develop mitigation plans to help ensure consumers can connect to coverage.

Coordinating Enrollment Across Health Coverage Programs

Coordination between Medicaid, CHIP, and the Marketplace will be key for achieving the ACA’s no wrong door approach to coverage. States have the option to decide whether the Marketplace (State-based (SBM) or Federally-facilitated (FFM)) will determine eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP or assess potential eligibility and send the case to the Medicaid and CHIP agency for a final determination.2 To facilitate coordination across programs and prevent individuals from having to provide information more than once, state agencies and Marketplaces are expected to electronically transfer an account with all of the individual’s information promptly and without undue delay and are not allowed to request any information or documentation that the individual has already provided.

Coordination processes will vary based on whether the Marketplace has the authority to assess or determine Medicaid eligibility. For example, if an individual applies through a Marketplace that determines Medicaid/CHIP eligibility, the Marketplace will make a final eligibility determination and transfer the account of any eligible individual to the Medicaid/CHIP agency for enrollment, without a second review of eligibility. In contrast, if an individual applies through a Marketplace that assesses Medicaid/CHIP eligibility, it will transfer the account for any individual assessed as potentially eligible for Medicaid/CHIP for a final determination by the Medicaid/CHIP agency. If determined eligible for Medicaid/CHIP, the individual will be enrolled. If determined ineligible for Medicaid/CHIP, the agency will transfer the individual’s account back to the Marketplace for a review of eligibility for premium tax credits. As a result, some individuals may be transferred back and forth between coverage programs before they are determined eligible. Among the 34 federal or partnership Marketplace states, as well as Idaho and New Mexico (which are initially relying on the FFM to handle Marketplace eligibility and enrollment), the FFM will assess Medicaid/CHIP eligibility in 24 states and make final Medicaid/CHIP eligibility determinations in 12 states. In seven (7) of these 12 states, the FFM will make determinations temporarily until the state’s Medicaid/CHIP eligibility system is able to meet the ACA requirements (Appendix Table 5).

The ability to electronically transfer individual accounts between state Medicaid/CHIP agencies and the Marketplaces is in various stages of development. All but two (2) of the 17 states with SBMs share an integrated or linked technology system that determines eligibility for all insurance affordability options and facilitates the next steps for enrollment. However, in states using the FFM, electronic transfers of individual accounts between the Marketplace and Medicaid/CHIP agencies are essential for coordinating enrollment. Due to ongoing technological challenges with the FFM, these transfers have been delayed. As such, alternative strategies have been put into place. For example, until the FFM can begin transferring electronic accounts to state Medicaid and CHIP agencies, it is sending batches with basic data on individuals the FFM has assessed as potentially eligible for Medicaid/CHIP. Similarly, if a state Medicaid/CHIP agency is unable to screen for premium tax credits and transfer the account to the FFM it can advise potentially-eligible individuals to apply directly through the FFM. Moving forward, implementing electronic account transfers will be key to minimizing burdens on consumers and ensuring that they only need to submit a single application, as envisioned by the ACA’s no wrong door approach to coverage.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

Beginning in January 2014, states are expected to rely on trusted electronic data sources rather than paper documentation to verify eligibility. Only when information cannot be obtained through an electronic data source or is not ‘‘reasonably compatible’’ with information provided by the consumer can additional information, including paper documentation, be requested. To facilitate electronic verification, states are expected to establish data linkages with federal and state data sources. A federal data hub provides access to information from multiple federal agencies including the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). In addition, states are commonly accessing databases that collect state wage information, unemployment compensation information, vital statistics, and eligibility data for other public programs. Ultimately the goal is for these data interfaces to provide real-time or immediate access to data, however, in some cases, data may continue to be exchanged in a process that “batches” requests for information for multiple people on a daily or other periodic basis. In these instances, data is also returned in batches, which may result in a lag before the requested data is available and can be used to verify eligibility. When this is the case, states may pend or hold the application until the data is received and reviewed. Alternatively, some states may use the data to verify eligibility after they have enrolled the individual based on his/her self-attestation.

States are submitting verification plans to CMS, which outline the electronic data sources and procedures they will use to verify eligibility criteria. For the majority of states, the heightened reliance on electronic verification requires a redesign of business practices to implement a real-time, data-driven approach to verification. Each state must file a plan with CMS describing the agency’s verification policies and procedures including the data sources used at application and renewal, the frequency of data checks, and how the state determined the usefulness of electronic data sources.3 While there is no formal process for federal approval, the verification plans are used to confirm state implementation of the new standards established by the ACA, and will be used for quality and audit purposes going forward.4 As of November 15, 35 verification plans have been approved and made publicly available.

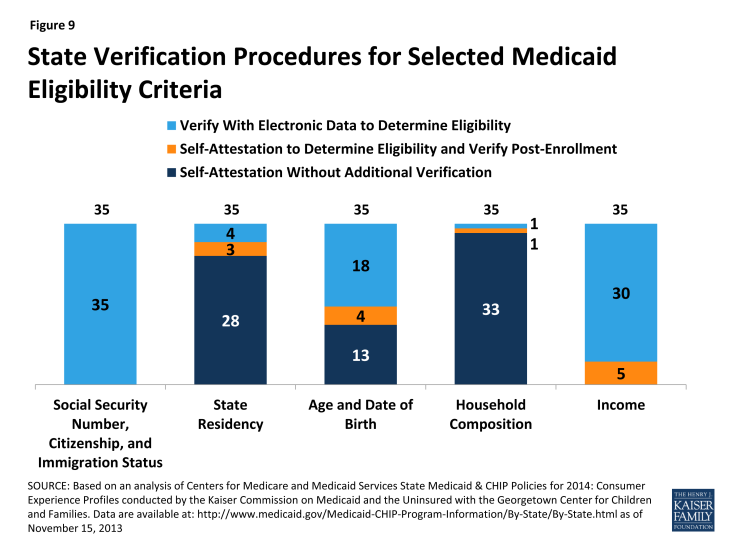

States continue to have the option to accept self-attestation for all non-financial eligibility criteria except where otherwise required by statute. Under law, states must verify Social Security Numbers (SSNs), citizenship, and immigration status. For other non-financial aspects of eligibility (e.g., state residency, age/date of birth, and household composition), states have more flexibility and may choose 1) to rely on self-attestation without additional verification, 2) rely on self-attestation to make the eligibility determination and verify post-enrollment, or 3) verify data to determine eligibility. For pregnancy, states must accept self-attestation, although they may request verification if multiple babies are expected. If states verify non-financial eligibility criteria, they are expected to use electronic data and eliminate or minimize requirements for paper documentation at both application and renewal. Even in states accepting self-attestation without further verification, the state may have access to electronic data for some people (for example, if the consumer is also enrolled in SNAP), which may be used to confirm eligibility.5 Moreover, states always have the option to verify any data that it considers questionable. All 35 reporting states will verify SSNs, citizenship, and immigration status through federal data sources as required by law. Most states plan to rely on self-attestation of state residency (28 of 35) and household composition (33 of 35). In contrast, the majority of the reporting states (22 of 35) plan to verify age and date of birth, with 18 verifying data to make the eligibility determination and 4 doing so post-enrollment (Figure 9 and Appendix Table 6).

For income, states must verify financial information from an electronic data source; however, this can be done post-enrollment after the state determines eligibility based on the individual’s attestation.6 States also may accept self-attestation for certain types of income that cannot be verified through an electronic source. All 35 reporting states will verify income through electronic sources, with 30 states doing so to determine eligibility and five (5) states verifying income post-enrollment (Figure 9 and Appendix Table 7). In addition, 23 states will be conducting routine ongoing post-enrollment checks of financial information to identify changes in income over time, although the frequency of these checks varies. Consumers are still required to report changes that may impact their eligibility.

States are relying on a variety of data sources to verify eligibility criteria. States have latitude to determine if a particular income data source is “useful” but neither the age nor cost of obtaining the data can be used as a reason to continue requiring paper documentation. SSNs and citizenship will be verified via an electronic match with the SSA, while immigration status will be verified through the DHS Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) database. Frequently-used data sources for other non-financial eligibility criteria include the SSA, the Public Assistance Reporting Information System (PARIS), and state databases, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), vital statistics, and public assistance records for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and SNAP. The most common data sources that states will use to verify income at application, renewal and post-enrollment include the IRS, SSA, state wage data, state unemployment data and commercial databases that provide payroll information for some employers, such as TALX (also known as the Work Number) (Appendix Table 8).

States may set “reasonable compatibility” standards to address situations in which self-attested income and electronic sources are inconsistent. In Medicaid and CHIP, data are always considered reasonably compatible if the individual’s self-attested income and the electronic data source are both at, below, or above the income standard—in these cases, the difference does not impact eligibility. In cases where self-attested income is above the standard and electronic data are below, or vice versa, states have flexibility to define when inconsistencies between the two sources are considered reasonably compatible. If the difference between the electronic data and the consumer’s self-attestation is within the reasonable compatibility standard, the self-attestation is used. If the data are not reasonably compatible under this standard, the state may accept a reasonable explanation of the difference and/or request paper documentation of income

- For cases in which self-attested income is below the income standard, but electronic data sources show income above the standard, 27 of the 35 reporting states have set a reasonable compatibility standard. If the data are not within the reasonable compatibility standard, 26 of the 35 states will ask for a reasonable explanation of the difference before requesting paper documentation, while nine (9) will always request paper documentation to verify income.

- For cases in which self-attested income is above the income standard, but electronic data sources show income below the standard, the vast majority of states are not setting a reasonable compatibility standard. Thirty (30) of 35 reporting states will accept the self-attestation, deny Medicaid eligibility, and screen for eligibility for premium tax credits, regardless of the size of the discrepancy between the attestation and the electronic data source. One state (NJ) will also accept self-attested income if the difference is no more than 10 percent, the state’s reasonable compatibility standard. Given that individuals may overstate their income if they are not aware that certain income and pre-tax contributions (e.g., dependent care expenses) should not be counted, this policy may result in a Medicaid denial and determination for premium tax credits even though the individual is, in fact, eligible for Medicaid. Three (3) states ask for a reasonable explanation of the difference before requesting paper documentation, while two (2) will always require paper documentation to verify income and process the eligibility determination.

|

Table 1: Reasonable Compatibility Approaches Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application

|

|

|

Total Number of States Reporting

|

35

|

|

If attestation and data are both

|

|

|

Below the income limit, determined eligible for Medicaid

|

35 (required)

|

|

Abovethe income limit, determined ineligible for Medicaid and screen for advance premium tax credits

|

35 (required)

|

|

If attestation is below and data are above the income limit:

|

|

|

Determine eligible for Medicaid if within reasonable compatibility standard

|

27

|

|

If not within the reasonable compatibility standard:

|

|

|

Ask for reasonable explanation from individual

|

26

|

|

Require paper documentation of income

|

9

|

|

If attestation is above and data are below the income limit:

|

|

|

Determine ineligible for Medicaid, screen for advance premium tax credits

|

30

|

|

Ask for a reasonable explanation of the difference from the individual*

|

3

|

|

Require paper documentation of income

|

2

|

|

*Note if the reasonable explanation is not sufficient, states may ask for paper documentation.

Source: Based on analysis of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services State Medicaid & CHIP Policies for 2014: Medicaid/CHIP Verification Plans conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured with the Georgetown Center for Children and Families. Data are available at: http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-State/By-State.html

|

|