What Coverage and Financing is at Risk Under a Repeal of the ACA Medicaid Expansion?

As discussion about repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) unfolds, questions emerge about how a repeal may affect Medicaid. The specific effects would depend on many factors that are currently unknown, including whether there is a replacement for the ACA, what happens to federal Medicaid expansion funding, and whether broader changes to the underlying financing structure of the Medicaid program are made. While it is difficult to quantify the specific effects of a repeal given these unknowns, this issue brief examines the changes in coverage and financing that have occurred under the Medicaid expansion to provide insight into the potential scope of coverage and funding that may be at risk under a repeal. It finds:

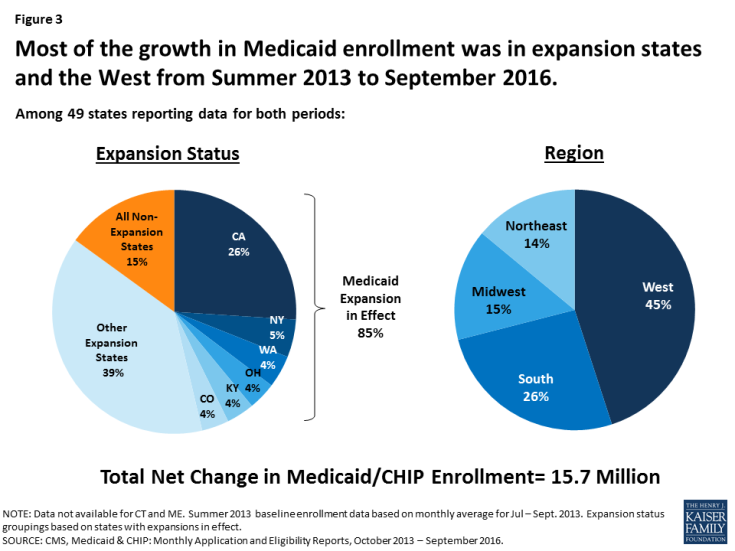

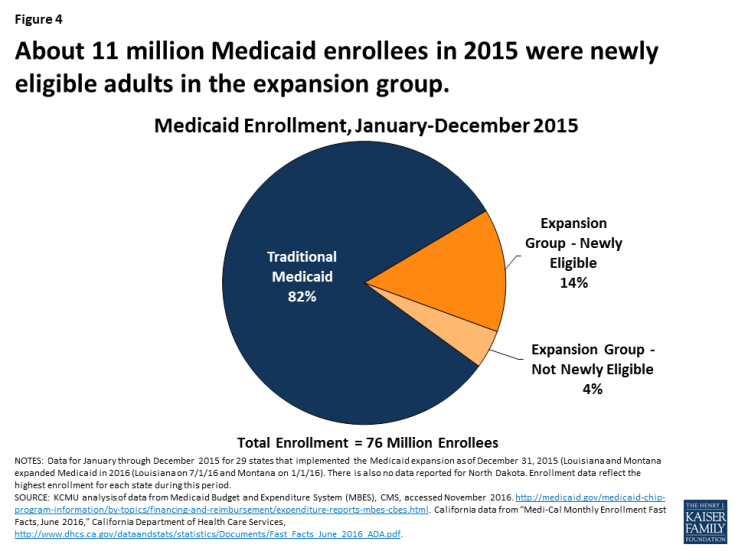

- In 2015, an estimated 11 million enrollees were adults made newly eligible by the expansion who could be at risk for losing Medicaid coverage. However, the scope of coverage losses among this group would depend on the specifics of the repeal and any replacement plan as well as actions by individual states. The Medicaid expansion made many parents and other adults newly eligible for the program, as there was no option for states to cover most adults without children through Medicaid before the expansion. This eligibility expansion, along with outreach and enrollment efforts associated with the ACA, led to large increases in Medicaid enrollment. Between Summer 2013, just prior to the ACA, and September 2016, there was a net increase in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment of 15.7 million people. In 2015, an estimated 11 million Medicaid enrollees were adults made newly eligible by the expansion. This number has likely continued to grow since 2015 as enrollment has continued to increase and additional states have expanded, including Louisiana and Montana.

- Loss of Medicaid coverage could reverse the progress in reducing the uninsured. The Medicaid enrollment gains contributed to a fall in the uninsured rate among nonelderly individuals, which declined from 16.6% in 2013 to a historic low of 10% in 2016.

- As a result of the enhanced federal funding for expansion, expansion states have received $79 billion in federal funding from January 2014 through June 2015. The ACA Medicaid expansion provides enhanced federal funding for newly eligible adults with no or little state matching dollars. Alaska, Louisiana and Montana, had not claimed spending for the expansion group during this period.

Why did the ACA Expand Medicaid?

The ACA’s coverage provisions built on and attempted to fill gaps in an insurance system that left many without affordable coverage. This system had built up over time and included employer-based coverage for many—but not all—workers and their families, Medicaid coverage for certain categories of low-income people, directly-purchased coverage for a small number of people who bought policies on the non-group market, and Medicare for most people over age 65 as well as some younger people with disabilities. Under this system, many were ineligible for coverage or could not afford coverage that was available. In 2013, 44 million nonelderly people were uninsured. The majority who lacked coverage were poor and low-income adults (28% of the non-elderly uninsured had incomes below poverty and 62% had incomes below 200% of poverty in 2013). The main reason that most people said they lacked coverage was cost.1

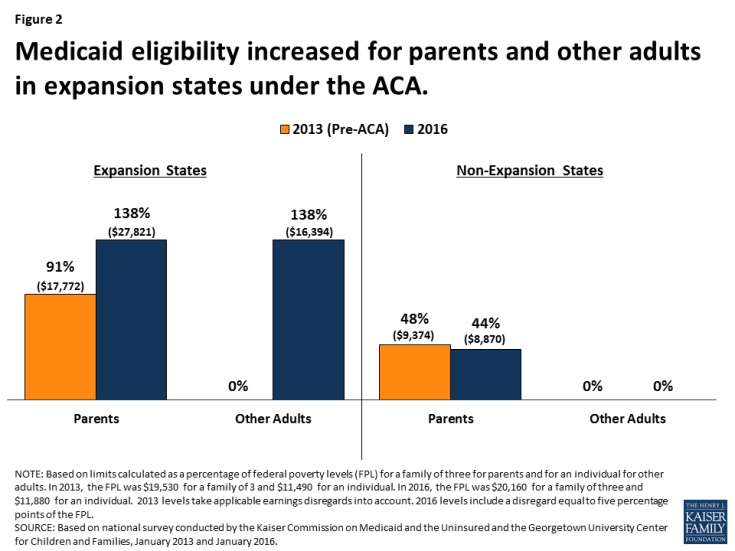

The ACA Medicaid expansion was designed to fill gaps in coverage for low-income adults. Prior to the ACA, Medicaid eligibility for adults was very limited resulting in large numbers of uninsured poor adults. Income eligibility limits for parents were very low in most states, often below half the poverty level, and other non-disabled adults generally were not eligible regardless of their income. The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility for parents and other adults to 138% FPL (about $16,000 for an individual or $28,000 for a family of three). Through this expansion and other changes, the ACA intended to establish a national minimum eligibility threshold in Medicaid of 138% FPL for nearly all individuals under age 65, making Medicaid the base of coverage for low-income people within the ACA’s broader coverage system. As enacted, this expansion was to occur nationwide beginning in January 2014. However, a 2012 Supreme Court ruling effectively made the expansion a state option.

In designing the ACA, expanding Medicaid was determined to be the most efficient and cost effective way to extend coverage to very poor adults. Medicaid had an existing role for the low-income population, and was already an operating program that could be extended rather than newly developed. Medicaid programs had experience providing coverage with low cost-sharing and comprehensive benefits suitable for a very low-income population. In addition, per capita spending in Medicaid is lower compared to private insurers after adjusting for the greater health needs of Medicaid enrollees.2

What Coverage is at Risk Under a Repeal of the Medicaid Expansion?

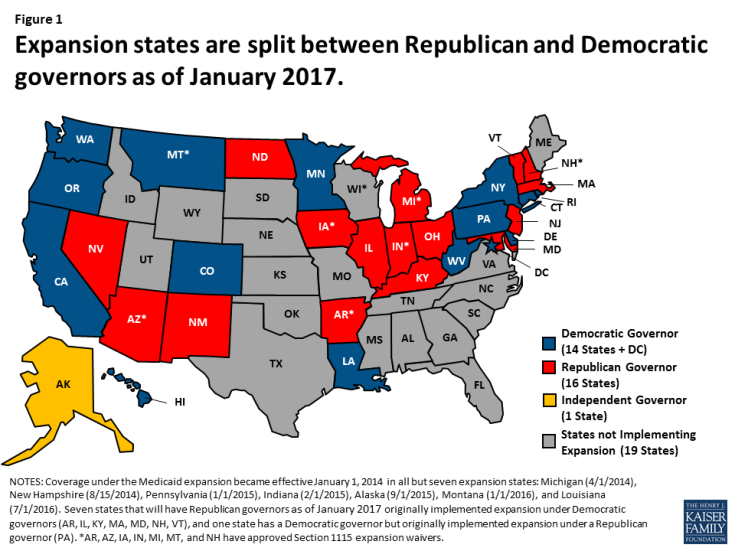

Under a repeal, many low-income parents and other adults could potentially lose eligibility for Medicaid. As of December 2016, 32 states including the District of Columbia implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion to adults. By January 2017, half (16) of the expansion states will have a Republican governor (Figure 1). Prior to the Medicaid expansion most states limited Medicaid eligibility for parents to less than the poverty level, and there was no option available to states within to cover other non-disabled adults within Medicaid (Appendix Table 1). As such, in expansion states, median eligibility increased from 91% to 138% FPL for parents ($27,821 for a family of three) and from 0% to 138% FPL for other adults ($16, 394 for an individual) (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 1 for state by state eligibility levels). In contrast, in non-expansion states, median eligibility for parents remains below half the poverty level and at 0% FPL for other adults.3 What would happen to eligibility levels would depend on the specifics of changes to federal eligibility rules under a repeal, including whether states would still have an option to cover adults, as well as other state choices. If states returned to their pre-ACA 2013 eligibility levels or lower, many parents and other adults would lose Medicaid eligibility in expansion states.

Figure 1: Expansion states are split between Republican and Democratic governors as of January 2017.

Figure 2: Medicaid eligibility increased for parents and other adults in expansion states under the ACA.

Decreases in eligibility would lead to declines in Medicaid enrollment, particularly in expansion states. Since the ACA coverage expansions were implemented starting in 2014 through September 2016, net Medicaid and CHIP enrollment has increased by 15.7 million, or 28% with the majority of growth occurring in expansion states. This growth included enrollment of newly eligible adults as well as children and adults who were previously eligible but not enrolled. Most growth was in large states in the West that expanded Medicaid (Figure 3). States that expanded Medicaid had over three times greater enrollment growth compared to non-expansion states (36% vs. 12%), although there was variation across states. If parents and adults were to lose eligibility for Medicaid, there would be declines in Medicaid enrollment, and most of these declines would likely be in areas that experienced the largest growth under expansion.

Figure 3: Most of the growth in Medicaid enrollment was in expansion states and the West from Summer 2013 to September 2016.

About 11 million Medicaid enrollees who were made newly eligible by the ACA Medicaid expansion would be at risk for losing Medicaid coverage if states no longer have an option to extend Medicaid eligibility to low-income adults and if federal enhanced financing is withdrawn under a repeal. The majority (82%) of Medicaid enrollees are eligible through pathways that existed prior to the ACA (e.g. children, pregnant women, elderly and individuals with disabilities). In addition, a small share of enrollees in the expansion group were eligible for Medicaid through pre-ACA expansions to adults.4 However, in 2015, about 11 million enrollees were adults in the expansion group who were made newly eligible by the ACA Medicaid expansion, accounting for 14% of all Medicaid enrollees (Figure 4 and Appendix Table 2 for state by state enrollment). Since 2015, this number has likely grown as enrollment has continued to increase and additional states have expanded, including Louisiana and Montana. Moreover, as of January 2016, an estimated 6.4 million adults were eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled, which include many newly eligible adults.5

Figure 4: About 11 million Medicaid enrollees in 2015 were newly eligible adults in the expansion group.

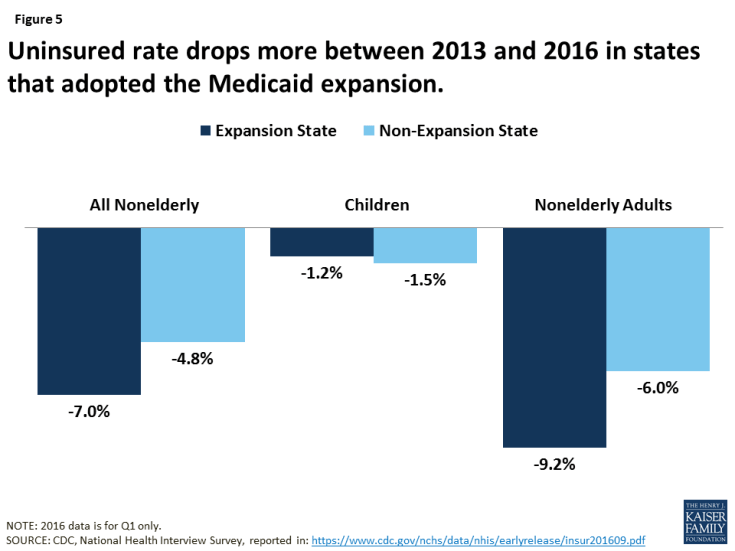

Uninsured rates could rise due to losses in Medicaid coverage, but, the extent of such losses would depend on what other coverage options may be available. Medicaid enrollment gains have played a significant role in decreasing the uninsured rate. Since implementation of the ACA, the uninsured rate among the nonelderly has fallen from 16.6% to a historic low of 10% in early 2016.6 Over 17 million more people have health coverage in 2016 compared to 2013, as the number of nonelderly uninsured dropped from 44 million to 27 million. Because the ACA coverage expansions mostly target adults, who have historically had higher uninsured rates than children, nearly the entire decline in the number of uninsured people has occurred among adults. Moreover, the decline in the uninsured rate for adults was larger among Medicaid expansion states compared to non-expansion states (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Uninsured rate drops more between 2013 and 2016 in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion.

What Financing is at Risk Under a Repeal of the Medicaid Expansion?

The law provided enhanced federal funding for states to implement the Medicaid expansion. Under current law, Medicaid provides a guarantee to states for federal matching payments. The federal share of Medicaid is determined by a formula set in statute that is based on a state’s per capita income. The formula is designed so that the federal government pays a larger share of program costs in poorer states. The federal share (FMAP) varies by state from a floor of 50% to a high of 74% in 2016, and states may receive higher FMAPs for certain services or populations. The ACA provided states 100% federal funding for the costs of adults made newly eligible under the Medicaid expansion from 2014-2016 with the federal share phasing down to 95% in 2017 and to 90% by 2020 and beyond.

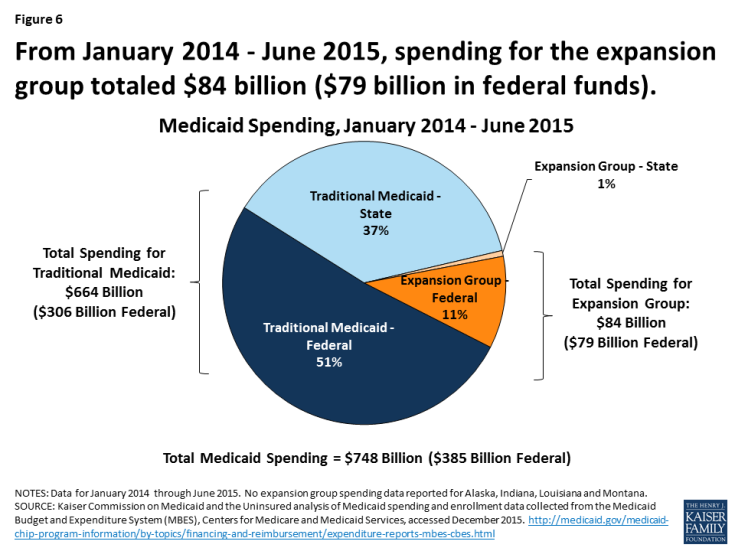

Under a repeal, states could potentially lose access to the enhanced federal funding made available for the Medicaid expansion. From January 2014 through June 2015, spending for the new adult group was $84 billion for the expansion group, accounting for about 12% of total Medicaid spending across all states over the period (Figure 6 and Appendix Table 3 for state by state spending). Nearly all expenditures for the new adult group ($79 billion out of $84 billion) were paid for with federal funds, reflecting the enhanced federal match for newly eligible adults.7 In contrast, federal funds comprised 58% of the costs for the traditional Medicaid population over the same period. Some states that implemented the expansion after January 2014, including Alaska, Louisiana and Montana, had not claimed spending for the expansion group during the data collection period.

Figure 6: From January 2014 – June 2015, spending for the expansion group totaled $84 billion ($79 billion in federal funds).

Broader economic gains states have realized as a result of the Medicaid expansion could be affected. National, multi-state, and single-state studies show that states expanding Medicaid under the ACA have realized budget savings, revenue gains, and overall economic growth despite Medicaid enrollment growth initially exceeding projections in many states.8 Studies show that states have achieved net positive economic impacts from increased employment; increased revenues to hospitals, physicians, and other providers; decreases in uncompensated care; and savings in other states programs, such as state-funded behavioral health or corrections.

Conclusion

As a new Administration and Congress debate a repeal of the ACA, it is important context to note that many Americans have favorable opinions of many individual provisions in the ACA with 8 in 10 (and two-thirds of Trump voters) who have a favorable opinion of giving states the option of expanding their existing Medicaid program to cover more low-income uninsured.9 Thirty-two states have implemented the Medicaid expansion, and as of January 2017, 16 of these states will have Republican governors. While it is difficult to quantify the specific effects of a repeal of the ACA Medicaid expansion given the many uncertainties that remain at this time, examining the changes in coverage and financing that have occurred under the Medicaid expansion provides insight into the potential scope of coverage and funding that may be at risk under a repeal. Experience to date suggests that under a repeal of the Medicaid expansion, many low-income parents and other adults would be at risk for potentially losing eligibility for Medicaid, which might contribute to increases in the number of uninsured, depending on what coverage options are available under a repeal. Moreover, states could lose access to the enhanced federal funding made available for newly eligible adults under the Medicaid expansion and face increased costs associated with rises in uncompensated care and spending in state programs for the uninsured.