Data Note: Balancing on Shaky Ground: Women, Work and Family Health

Women now comprise nearly half of the nation’s workers, and 70% of mothers with children under age 18 are in the labor force.1 In September 2014, the U.S. Census Bureau released national statistics on poverty and income, reporting that 16% of women live below the poverty line and that median earnings for women are only 78% of men’s earnings, a gap that has persisted for several years.2 Policy makers across the political spectrum have forwarded proposals to shore up economic security for “working families.”3 ,4 ,5 Much of the national discussion has focused on policies related to income, such as minimum wage, tax credits, salary transparency, job training, and the wage gap, all of which are important issues for women. For many working women, economic security also encompasses health issues, including workplace benefits such as insurance coverage, paid sick leave, and paid family leave.

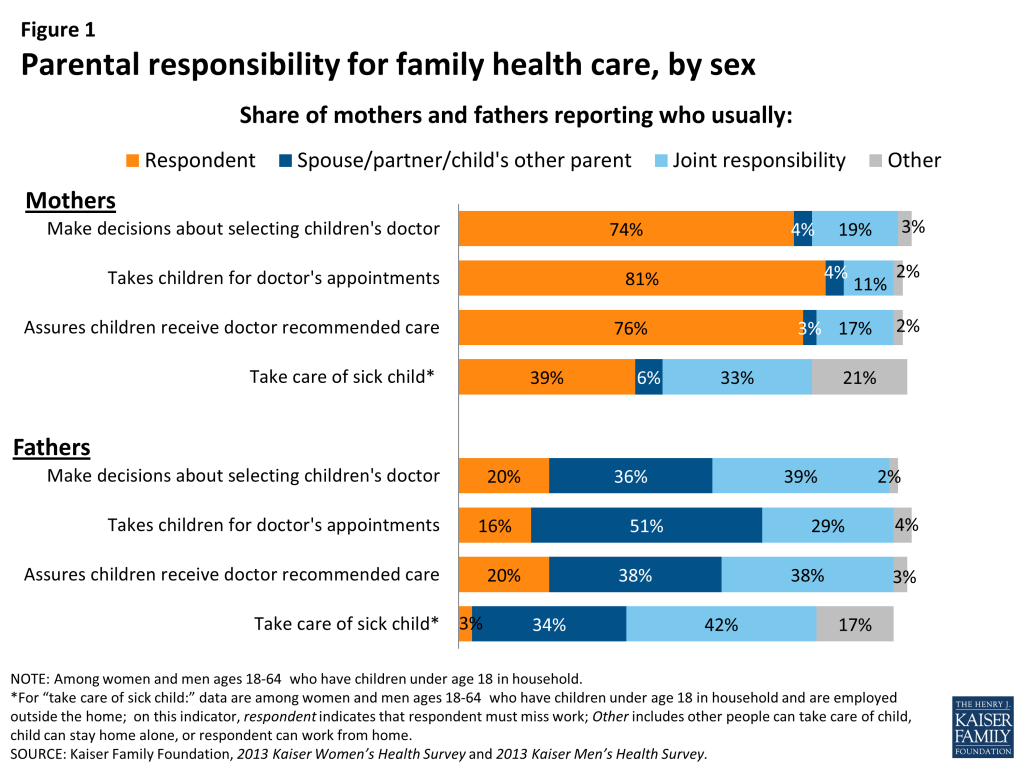

In most households, women are the managers of their families’ health, as illustrated clearly in Figure 1, which is based on data from a recent national Kaiser survey of women and men about their health care experiences. Among mothers, about three-quarters report that they are the ones who take charge of health care responsibilities such as choosing their children’s provider, taking them to appointments, and following through with recommended care, compared to approximately a fifth of fathers.

This gender difference extends to working parents as well. Four in ten working mothers (39%) must take time off and stay home when their children are sick, over ten times the share of men (3%). Fathers also agree that moms are the leaders of children’s health care needs, though a substantial share of both mothers and fathers say they share responsibility for these tasks.

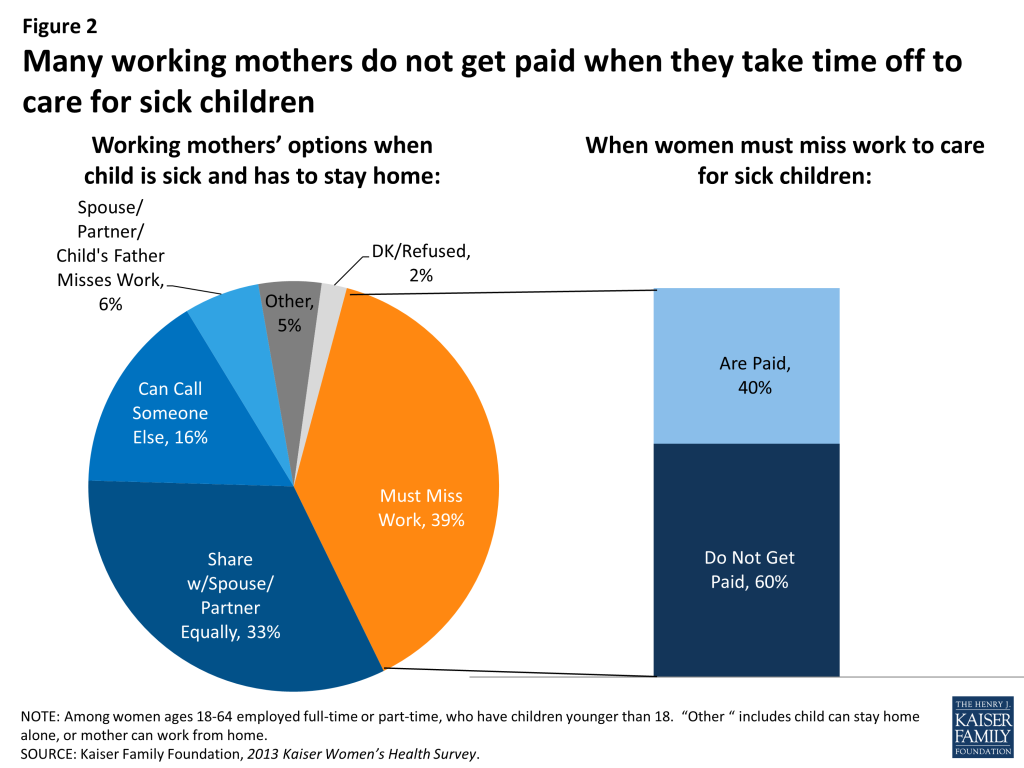

Caring for children’s health has tangible economic consequences, especially for women. Among the mothers who do not have other child care options and must miss work when their children are sick, 60% are not paid for that time off (Figure 2), up significantly from 45% in 2004.6 When two-thirds of school aged children nationally miss at least one school day during the year because of illness or injury, and nearly one-fifth miss more than a week, this is a common occurrence.7

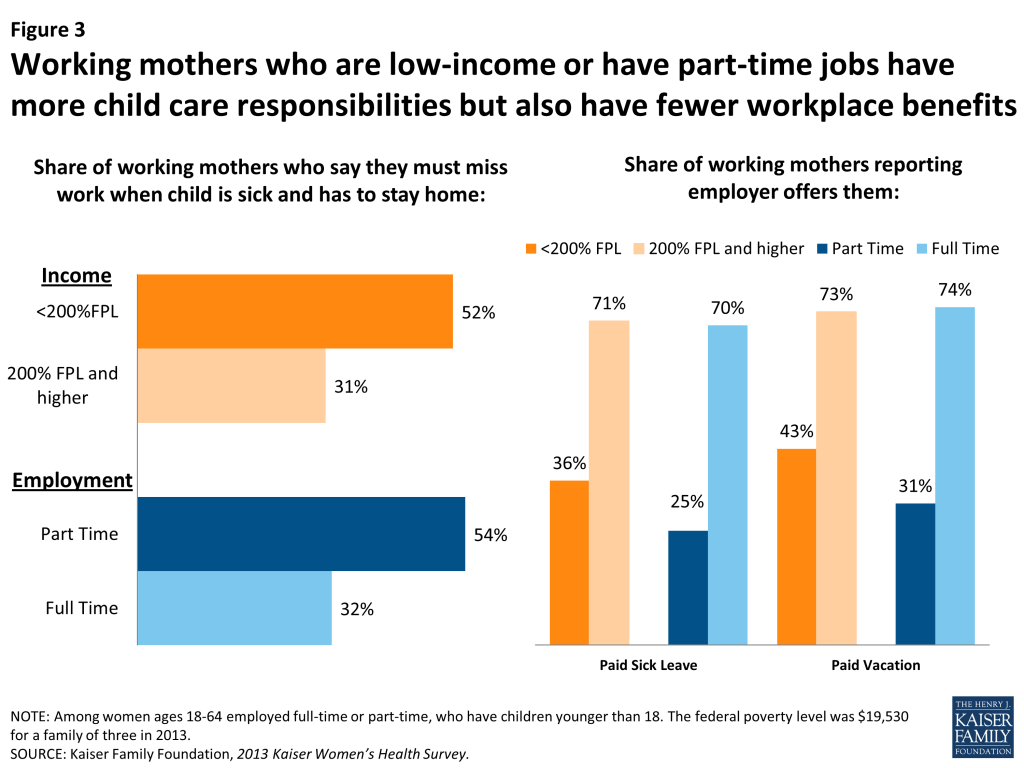

Workplace benefits are an important part of the story. So called “fringe benefits” such as paid leave and health insurance can help employees meet their personal and family health care needs while also fulfilling their work responsibilities. About six in ten working moms report that they are offered paid sick leave (56%) and paid vacation (61%).8 For mothers on the lower end of the economic scale and those in part-time jobs, the need for these supports is even greater. More than half must take time off when their children are sick, compared to about a third of their higher income and full-time counterparts, who are more likely to have others to help with childcare (as well as have money to pay for sitter services). Yet, there is a large disparity in workplace benefits, with offer rates of paid sick leave and paid vacation significantly lower among mothers who are low-income or part-time employees (Figure 3).

A public policy response that addresses women’s economic security and “balance” with health, family, and work issues has been elusive. Nationally, the landmark Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) that gives eligible employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to care for seriously ill family members, the arrival of a child, and job protection when an employee returns from family or medical leave has been in place for more than 20 years. As a result of the law’s protections, millions of workers have benefited from job security while caring for loved ones. Despite the important safeguards the law provides, many working women simply cannot afford to take extended leave without pay.

There have been a number of efforts to build upon the FMLA and enact national paid leave policy; however, they have largely stalled in a polarized Congress. Proponents urge that paid leave would provide employees with greater financial security when they must take an extended leave for medical reasons or to care for an ailing family member or new child.9 Opponents cite concerns about the impact of new federal requirements on local government and employers as well as the financial implications a new benefit would have on wages and employment.10 Most of the policy action has been at the state and local levels. Three states (California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island)11 have enacted laws offering eligible employees partial paid family leave.12 In addition to paid family leave, the last few years have seen some momentum at the local level for paid sick days. Since it was first passed by voter initiative in 2006 in San Francisco, several more cities across the nation as well as two states (Connecticut and California), have enacted some form of paid sick days, which enables women to get paid time off when they or their children get a minor illness and need to stay home for short periods. Paid sick days allow workers to take time off for medical appointments or to address a health condition for themselves or a family member without losing pay. Several of these laws also specifically allow workers to use paid sick days for reasons related to sexual assault or domestic violence.

Women have always been the primary caregivers for their family’s health needs, be it for their children, parents, or other family members. Despite the consistent rise in the share of women participating in the workforce, there has been relatively little policy response to the often dueling responsibilities that women have to their families and to their jobs. For many women, missing work when their children have a cold or upset stomach has a cost. The price is especially high for low-income working mothers, who have fewer childcare and financial resources, and often limited workplace benefits. For these women, who must balance workplace and family health responsibilities with the fewest supports, the current system leaves them on shaky ground.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Women of Working Age, 2013. ↩︎

- U.S. Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the U.S., 2013. Wage gap data represents the dollar earnings ratio between women and men who are full time, year round workers. ↩︎

- Office of U.S. Senator Mike Lee, Family Fairness and Opportunity Tax Reform, accessed October 5, 2014; Lee M. and M. Rubio, A Pro-Family, Pro-Growth Tax Reform, Wall Street Journal, September 22, 2014. ↩︎

- White House Summit on Working Families, 2014. ↩︎

- Office of U.S. Senator Deb Fischer, Fischer, Collins, Ayotte, Murkowski Offer Amendment to Help Address Gender Pay Discrimination, 2014. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Women and Health Care: A National Profile, 2005. ↩︎

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), National Quality Measures Clearinghouse, Missed School Days, 2013. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. ↩︎

- National Partnership for Women and Families, The Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, February 2014. ↩︎

- The National Coalition to Protect Family Leave, Paid Leave, accessed October 13, 2014. ↩︎

- The state of Washington has also passed a law providing paid leave to care for the arrival of a child, but it has not yet been implemented and there is no projected date for implementation. ↩︎

- National Partnership for Women and Families, State Paid Family Leave Insurance Laws, October 2013. ↩︎