Medicare’s Role for Older Women

Medicare is the federal health program that provides health coverage to 50 million Americans ages 65 and older and younger adults with permanent disabilities. While Medicare plays an important role for nonelderly people with disabilities, Medicare is also a critical source of retirement security for 22.4 million women ages 65 and over, who tend to have lower incomes and more chronic conditions than older men. More than half (56%) of all older Medicare beneficiaries are women; two of every three beneficiaries ages 85 and older are women. As policymakers consider changes to Medicare to reduce the national deficit and control rising health costs, older women have much at stake in the outcome of discussions about the program’s future.

Medicare’s Structure

Medicare helps pay for basic medical care, and is organized into four distinct parts:

- Part A covers inpatient hospital care, skilled nursing facility care after a hospital stay, hospice and home health services.

- Part B covers physician services, outpatient hospital care, mental health services, home health, x-rays, diagnostic tests, durable medical equipment, and preventive services.

- Part C (Medicare Advantage) provides benefits covered under Parts A and B (and often Part D) through private health plans, such as HMOs and PPOs.

- Part D provides prescription drug coverage through private plans (stand-alone drug plans and Medicare Advantage plans), with additional premium and cost-sharing subsidies for beneficiaries with limited incomes and assets.

Health and Long-Term Care Needs

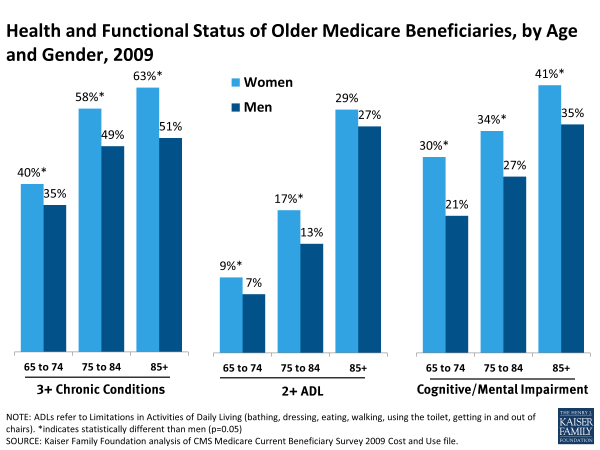

Older women on Medicare have significant health needs. Women live longer than men, on average, and a greater share of older women than older men face health and functional problems. Older women experience some multiple chronic conditions (such as arthritis, osteoporosis, and hypertension) at higher rates than older men, and this gender gap persists as they age. (Exhibit 1).

In addition, older women have higher rates than older men of functional impairments, such as limitations in activities of daily living, and cognitive impairments, such as memory loss and dementia, that can hinder their ability to live independently. Many older women also lack the social supports needed to live independently. They are considerably more likely than their male counterparts to be widowed (44% versus 14%) and live alone (38% versus 19%). As women age and their health needs grow, these social challenges translate into greater use of long-term care services and supports. Older women represent seven in 10 (72%) of all Medicare beneficiaries living in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term care facilities. Yet Medicare only offers time-limited coverage for long-term care services provided in facilities or in the community. This coverage limitation exposes many women to high out-of-pocket spending when they can no longer live independently and need care for extended periods of time.

Income and Financial Security for Older Women

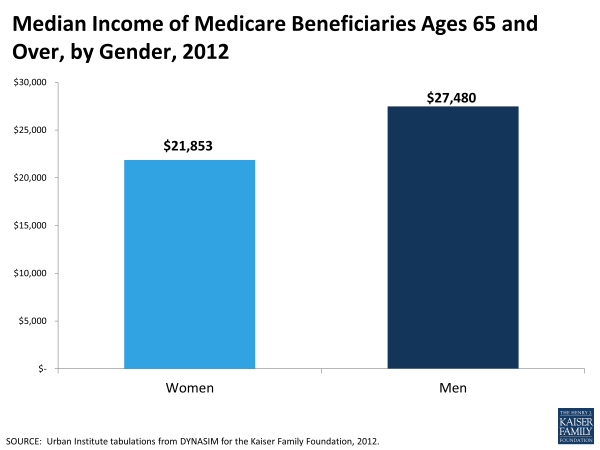

Older women receive lower average Social Security and pension benefits than men, primarily because they had lower-paying jobs than men during their working years and because many worked part-time or left the workforce for periods of time to raise families or care for aging family members. Among Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older, women have lower median per capita income than men ($21,853 compared to $27,480 in 2012), as well as lower median combined value of financial assets and retirement savings ($65,802 versus $93,371 in 2012) (Urban/KFF analysis). (Exhibit 2).

Medicare Benefit Gaps and Cost Sharing

Despite providing important benefits, Medicare has gaps in coverage and does not cover hearing aids, eyeglasses, or dental care, nor does the program cover extended nursing home stays or personal care needs. In addition, Medicare charges relatively high cost sharing, including deductibles of $1,184 per benefit period for Part A inpatient care, $147 for Part B medical services, and $325 for Part D drug benefits. In addition, many Medicare benefits, including physician visits and prescription drugs, are subject to copayment or coinsurance. Medicare Parts A and B also have no limit on out-of-pocket spending.

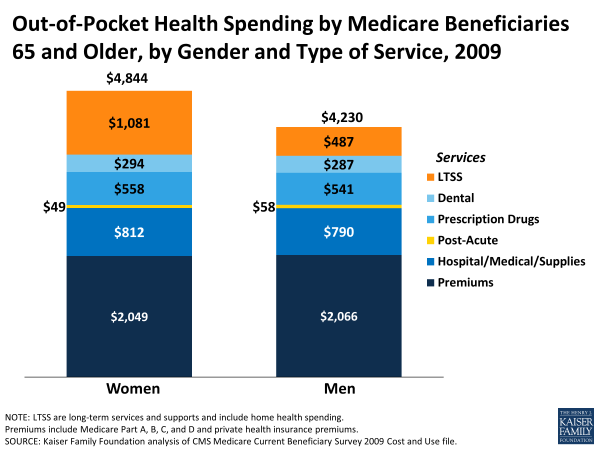

Exhibit 3: Out-of-Pocket Health Spending by Medicare Beneficiaries 65 and Older, by Gender and Type of Service, 2009

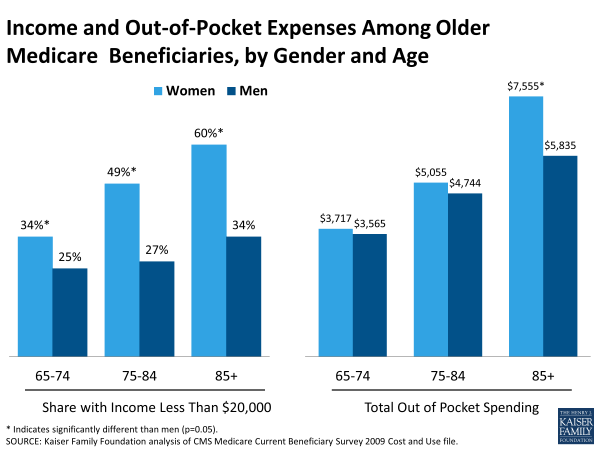

These gaps in benefits and cost-sharing requirements, together with spending for premiums for Medicare and supplemental coverage (described further below), can translate into high out-of-pocket expenses for people on Medicare. On average, older women spent more on health care (including premiums) than older men in 2009 ($4,844 versus $4,230), a greater financial burden given their lower incomes. Notably, older women spent more than twice as much on average for long-term services and supports (LTSS). (Exhibit 3) For all older Medicare beneficiaries, out-of-pocket spending escalates as they age, but women ages 85 and older have considerably higher out of pocket costs than older men, largely due to their higher health and social needs and greater use of long-term care services. Often the need for these services comes at the time when women have fewer resources. Among women ages 85 and over, out-of-pocket spending amounts and the share with low incomes are higher than for younger women and men of all ages on Medicare (Exhibit 4).

Out-of-pocket spending by women ages 85 and older averaged $7,555 in 2009, compared to $5,835 for men ages 85 and older, while 60 percent of women ages 85 and older had annual incomes below $20,000, compared to 34 percent of men ages 85 and older. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 made some improvements in Medicare coverage that may reduce some out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries, including the elimination of cost sharing for many preventive benefits important to women’s health, such as screenings for cancer, chronic diseases, and osteoporosis, and the addition of a new no-cost annual wellness visit. The law also phases out the Part D drug benefit’s coverage gap, commonly known as the “doughnut hole,” by 2020.

Supplemental Health Insurance

To help cover Medicare’s benefit gaps and cost sharing, the majority of people on Medicare have some form of supplemental health insurance, either as a benefit from their employers, coverage that they purchase separately, or through Medicaid because they are poor.

Employer-Sponsored Insurance supplements Medicare for many retirees and spouses, and also covers some working seniors for whom the employer plan (rather than Medicare) is their primary source of insurance because they or their spouse are still working. A smaller share of older women than older men on Medicare have employer-sponsored coverage (36% versus 42%, respectively), largely due to the nature of women’s workforce participation prior to their retirement when they were more likely to work part-time or part year and therefore less likely to qualify for retirement benefits.

Medigap insurance policies are typically purchased directly by beneficiaries to help cover Medicare cost-sharing requirements; 22 percent of older women on Medicare have a Medigap policy, compared to 19 percent of older men.

Medicare Advantage plans provide all Medicare-covered benefits and many offer additional benefits, such as limited vision care. About one quarter of both older women (27%) and older men (25%) are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.

Medicaid is the federal-state health program for the poor and a critical source of supplemental coverage for 18 percent of older women on Medicare. In total, 9 million elderly or disabled Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes and limited resources also qualify for Medicaid; these beneficiaries are often referred to as “dually eligible.” In 2009, women comprised more than two-thirds (68%) of dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid enrollees ages 65 and older.

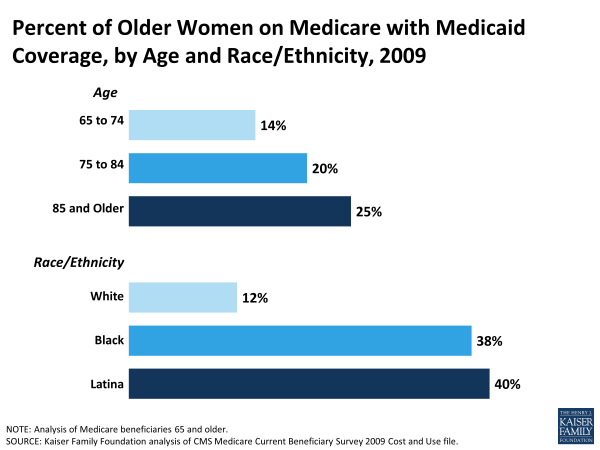

One quarter of women ages 85 and over and about four in 10 Black and Latina women on Medicare are also enrolled in Medicaid, largely due to their lower average incomes (Exhibit 5). In addition to being poorer, dually eligible beneficiaries tend to have worse health status and face more intensive health care needs than the general Medicare population. More than six in 10 (62%) of all older women in nursing facilities are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid.

No supplemental coverage is a concern for nearly one in ten (9%) older women on Medicare. Those without supplemental coverage typically report more cost-related barriers to care and lower rates of utilization than do beneficiaries with supplemental coverage.

Exhibit 5: Percent of Older Women on Medicare with Medicaid Coverage, by Age and Race/Ethnicity, 2009

Looking to the Future

Medicare plays a key role in health and retirement security for older women. Despite the importance of this coverage, gaps in benefits and high cost sharing lead many Medicare beneficiaries, particularly older women, to spend a substantial amount on their health and long-term care needs.

The future of Medicare is a key element of ongoing deficit reduction discussions. While some changes to Medicare under consideration could help to preserve Medicare for future generations of women, policy changes that would increase out-of-pocket medical spending could have a disproportionate impact on older women, many of whom have limited capacity to absorb additional costs given their high health needs and low incomes. The significant role that Medicare plays for elderly women underscores the importance of sustaining the program and the ongoing need to find ways to address the health needs and related financial challenges arising from health and long-term care expenses facing women as they age.