Medical Debt Among People With Health Insurance

How Does Medical Debt Become a Problem for People with Health Insurance?

Similar to the overall population, most of those we interviewed were insured as they incurred medical debt – most of them under job-based group health plans. All expected that health insurance would protect them from financial ruin if they would ever face a serious illness or injury, but that turned out not to be the case. Various features of their coverage contributed to medical debt problems, and are examined in more detail below.

In-Network Cost-Sharing

By far, the leading contributor to medical debt among people interviewed was cost-sharing for covered services received by in-network providers and facilities. Of the 23 people interviewed 17 reported high cost-sharing burdens. To some extent, “high” can be measured objectively, but affordability also depended on an individual’s income and other characteristics.

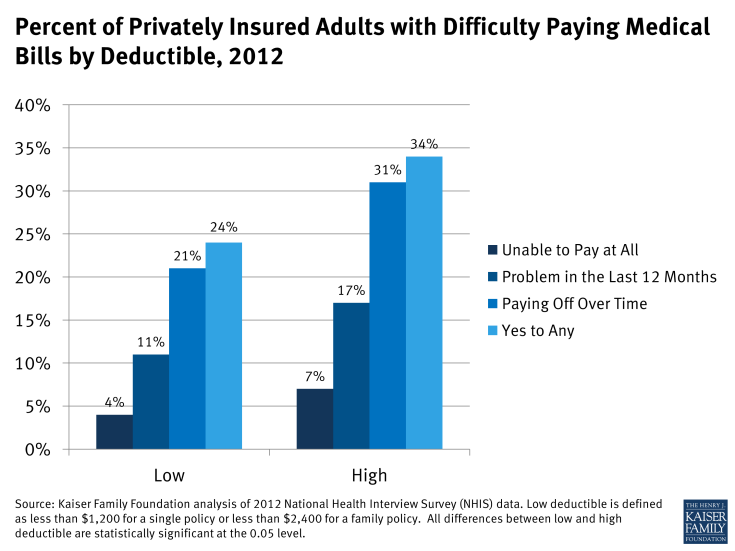

Case studies illustrated that cost-sharing need not be extremely high to be unaffordable. However, other research confirms that medical debt problems among the insured increase with higher levels of cost-sharing. For example, NHIS data show people in higher-deductible health plans are more likely (34%) to have difficulty paying medical bills compared to people in lower-deductible health plans (24%).

The amount of cost-sharing required under health insurance plans has risen steadily for years. As recently as 2006, only 10 percent of covered workers in group health plans faced an annual deductible $1,000 per person or more; today it 38 percent.1 For nine of our interviewees, the health plan annual deductible was $1,000 per person or less.

Figure 3: Percent of Privately Insured Adults with Difficulty Paying Medical Bills by Deductible, 2012

This trend in rising cost-sharing reflects a tradeoff in affordability of premiums and level of protection provided by a plan. However premium savings to an individual or family can be more than offset if they must satisfy the annual deductible or out-of-pocket limit on cost-sharing. Studies find that among people reporting problems paying medical bills, the average medical debt for the family was $6,500 in 2010.2 While many of the people we interviewed had medical bills in excess of that amount, six had unaffordable medical bills that totaled $5,200 or less. From their experiences, we observed several reasons why even a few thousand dollars in annual, in-network cost-sharing proved problematic:

Medical bills high relative to income and savings

Studies of medical bill burdens often use as a benchmark bills that exceed 10 percent of household income, though this level was selected somewhat arbitrarily.3 Twenty of the people we interviewed had medical bills exceeding this threshold. For those with limited incomes, even modest amounts of cost-sharing were unaffordable. Prescription drug copays were a struggle for Dorothy, for example. She earned $34,000 annually. The copays for her drugs totaled $150 each month, or more than five percent of her annual income. Then, when she was unexpectedly hospitalized and had to pay a $2,000 deductible in addition, the bills were simply more than she could manage.

None of the individuals interviewed had sufficient savings to pay their portion of covered, in-network medical bills. In this respect, they were similar to most Americans. According to the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, most U.S. households have very limited liquid assets (checking, savings, and money market account balances). See Table 3. The amount of liquid assets declines sharply as income declines. For those with incomes below 400% of the federal poverty level (two-thirds of the U.S. population), most have far less than $3,000 cash on hand. Taking into account other unsecured consumer debt (e.g., credit card and medical debt, but not mortgage or auto loans), most households with incomes below 400% of FPL have net negative financial assets. That is, their consumer debt exceeds their cash on hand. As a result, even modest deductibles and copays could pose affordability problems, particularly if cost-sharing expenses recur, as for chronic health conditions.

Among households with higher incomes – greater than 400% FPL – liquid assets are higher. The median amount of cash on hand for this income group is $12,000. Taking into account other unsecured consumer debt, however, most have net liquid assets of $5,200 or less.

|

Table 3. Median Household Liquid Assets and Net Financial Assets by Household Poverty Level

|

||

|

Income

(% Poverty Level)

|

Liquid Assets

|

Net Financial Assets

|

|

<100%

|

$100

|

$0

|

|

100% – 250%

|

$670

|

-$488

|

|

250% – 400%

|

$2,740

|

-$3,000

|

|

>400%

|

$12,000

|

$5,200

|

|

Source: KFF Analysis of Survey of Consumer Finances data, 2010.

|

||

Typical group health plan cost-sharing levels today exceed the amount of liquid cash balances most households have on hand. In group health plans, the average annual deductible in 2013 is $1,135 for single coverage; then additional cost-sharing expenses applied until the annual OOP maximum is reached. In 56% of group health plans today, the annual OOP maximum is less than $3,000 for a single person.4 Thus cost-sharing resulting from a single surgery could rapidly deplete liquid cash assets for most people. As high-deductible health plans become more prevalent, potential problems compound. In 2013 38% of workers have annual deductibles in excess of $1000 (single) and 43% have annual OOP maximums greater than $3,000. For many people covered under these plans, even with income above 400% FPL, an extended illness or chronic condition could easily result in unaffordable medical bills.

Cost-sharing “multipliers”

Many health plans are identified by the level of their annual deductible – for example, the “PPO 500.” The number signifies a single person’s potential deductible expense for a single plan year. In evaluating the protection offered by a policy, people may tend to focus on a single number – the annual deductible or annual limit on out-of-pocket cost-sharing (the OOP limit) – without realizing that this does not necessarily represent the extent of possible cost-sharing liability. In fact, individuals and families can incur multiples of these expense amounts, as several people we interviewed experienced.

Some examples of cost-sharing “multipliers” are listed below.

Treatments spanning two plan years – Several people interviewed had treatment that began toward the end of one plan year and continued into the next, effectively doubling their cost-sharing liability for a single treatment episode. George, for example, had surgery scheduled for the last month of a plan year; the following month he experienced post-operative complications, necessitating a second surgery. As a result he satisfied two annual deductibles and one and one-half annual OOP limits within a period of 4 months. Some health plans (though not George’s) include a carry-over feature that credits care received in the final months of a plan year toward the next plan year’s annual deductible.5

Family-level cost-sharing – Under family policies, cost-sharing expenses can also double if more than one person makes significant claims in a year. Elsie, for example, was covered by a health plan with $1,000 deductible per person. Once her son was born, his expenses were subject to a separate $1,000 deductible. Beyond the deductible, both mother and son were liable for additional cost-sharing expenses, up to an annual OOP limit. The year after giving birth, Elsie required surgery and her son was hospitalized twice before he turned three. By then, the family cost-sharing bills reached $20,000.

Cost-sharing for chronic conditions – Finally, it was common for cost-sharing bills to accumulate year after year when people had chronic conditions. While some could manage bills for a while, over time financial burdens compounded and became too great. Sonya, for example, struggled with repeated deductibles and copays over 16 years as she sought treatment for her child’s autism. Seventy-two million working age Americans have at least one chronic health condition.6 People with chronic conditions are much more likely to have high financial burdens for two consecutive years (29% to 56%, depending on the chronic condition) compared to those with no conditions or acute conditions (14% to 15%).7

Extremely high cost-sharing

Some people were covered by health plans that required very high cost-sharing for covered services, beyond what is required under typical health plans or what would be allowed under private plans starting in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act. For example, three of the people interviewed were covered by health plans with an annual out-of-pocket (OOP) limit on cost-sharing liability in network of $10,000 per person. One of these was a non-group plan; the other two were job-based group plans.

The health plan OOP maximum generally limits the amount of cost-sharing a person is responsible for in a year for in-network care. However, in at least two cases, the OOP limit was not, in fact, the maximum amount of cost-sharing that could apply. Under Gwen’s plan, for example, the OOP limit was in addition to her $3,000 annual deductible, not inclusive of that amount. Under Richard’s plan, the OOP limit did not apply to outpatient copays. His $40-per-visit-copay for physical therapy (three times per week for an extended period) added almost another $500 per month ($6,000 per year) to his medical bills.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation 2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey, most employer sponsored health plans have an annual OOP maximum on cost-sharing. For most plans, the annual OOP maximum is less than $3,000 per person; only 4 percent of covered workers are in plans with an OOP maximum of $6,000 or more. Under job-based plans today, however, most OOP limits are not all-inclusive. For about one-in-three workers enrolled in PPO plans with an OOP limit, the annual deductible does not count toward the OOP limit. And for most workers in plans with OOP limits today, cost-sharing for prescription drugs does not count toward the OOP limit.8

Out-of-Network Care

Another common problem observed in the case studies involved medical bills arising from care received out-of-network. Seven of those interviewed had unaffordable medical bills for out-of-network care. These bills proved particularly problematic for several reasons:

Fewer cost-sharing protections

Some health plans – usually HMOs – require all care to be received by network providers in order to be covered. Most others will cover out-of-network care, but at a lower level. Gwen and George’s case offered an example: Under their plan, a $3,000 annual deductible and $10,000 OOP maximum (in addition to the deductible) applied for in-network care; but amounts doubled for out-of-network care. With these high limits, George incurred $26,000 in out-of-network cost-sharing in less than one year.

“Inadvertent” out-of-network care

Often people received out-of-network medical bills from providers whom they never met or did not choose. This happened frequently among those who were hospitalized. Ben, for example, incurred unexpectedly high medical bills from a surgery, and almost one-third of what he owed was to the anesthesiologist, whom he met for the first time the day of the operation. Ben had been careful to select a surgeon and a hospital in his plan network; it didn’t occur to him that other doctors practicing within the hospital might not also be in network. “I found out one thing. Anesthesiologists are not part of the medical group. They’re not with anybody’s network. I guess they figured out if you need surgery, hey, you’re stuck with us! That was a surprising thing to me. It was only later I realized they’re not in any network.” Kris was another person who chose an in-network facility, but was billed by doctors working in the hospital who weren’t in the same network. “Most of what I owe is to doctors who treated me while I was hospitalized and I never saw them again out of the hospital. One allergist’s bill was close to $1,200 – that was my portion. I wish I knew why he was so expensive. He just came in the room twice and gave me a sheet saying what I should and shouldn’t do – he didn’t even write me a prescription. The doctor who was treating me in the hospital wanted to consult with this allergist. I didn’t contact him directly or select him.”

Gwen and George faced a somewhat different situation. Following surgery, George was so frail his doctor recommended recovery in the inpatient rehabilitation unit of the hospital. However, that unit was independently owned and operated by a separate company that did not participate in the plan network. Gwen was told the unit was out-of-network, but in light of her husband’s frail condition (and in light of substandard care they believed he had received previously from another in-network rehab facility) she felt she had no other choice. George’s share of the inpatient rehab bill alone was $23,000.

In general, hospitals do not require physicians to participate in the same plan networks as a condition of receiving hospital privileges, and health plans do not require hospitals to have such agreements with hospital-based physicians, though most plans acknowledge these specialties are critical to an adequate network precisely because patients have no choice in selecting them.9 Health plans report difficulty negotiating network agreements with hospital-based physicians (such as anesthesiologists, radiologists, and emergency physicians) and note these specialties are the most aggressive in seeking higher fees and typically have exclusive agreements with one or more hospitals in an area.10

Balance billing

In addition to Ben and Kris, Kieran had difficulty paying unexpected high medical bills that included balance billing. His wife, Jenna, experienced complications during her pregnancy and was hospitalized several times. Several doctors who treated her and the baby were out-of-network and billed the family more than insurance determined was reasonable. Out-of-network providers are not required to limit charges to the amount allowed by a health plan. When they don’t, patients can be liable for the balance of the charge above what their health plan allows in addition to higher cost-sharing. U.S. consumers pay an estimated $1 billion annually in balance billing charges.11 A study of Californians covered under job-based group plans found 11 percent experienced balance billing; among those who were hospitalized, 17% received at least some out-of-network care.12

Interestingly, though George owed thousands of dollars for his non-network care, he incurred very few balance billing charges. The couple’s health plan participated in a “Multiplan” agreement – essentially an independently organized provider network that supplemented the regular plan network. Nearly all of the non-network providers who cared for George participated in the Multiplan network. As a result, George’s health plan agreed to reimburse based on that network’s fee schedule and the providers agreed to refrain from billing above that amount.13

Another interviewee, Morgan, also escaped balance billing from non-participating providers. Morgan also chose an in-network hospital for his surgery, and then inadvertently received out-of-network care from doctors who practiced in that hospital. However, Morgan’s insurance policy included a feature that protected him from balance billing from non-network providers while in a network hospital. His insurance simply paid the entire billed charge of the non-network doctors. Morgan didn’t realize his policy included this feature until the bills arrived, though was thankful for it. Health insurers generally are not required to include such coverage of non-network balance billing.

Health Plan Coverage Limits or Exclusions

For several people interviewed, medical debt arose when health insurance simply did not cover the care they needed. Dillon, for example, was hit by an uninsured motorist in 2003. The accident totaled his truck and left him with chronic back pain and depression. His insurance, through a large employer health plan, didn’t cover the extensive physical therapy he needed; nor did it cover dental care needs – which, although unrelated to the accident, were also extensive. Dillon estimates his unpaid medical bills over several years reached $10,000-$20,000.

Maisy’s medical debt related to her husband’s mental health conditions. He suffered from panic attacks, depression and addiction, requiring extensive inpatient treatment and rehab over a period of six years starting in 2002. Claims following a suicide attempt weren’t covered by her large employer health plan, which excluded treatment for self-inflicted injuries. Maisy also expressed concern that under her policy, other inpatient stays were subject to strict utilization review and her husband was rarely allowed to remain inpatient for more than a few days. She worried this limited the effectiveness of treatment, prolonging his illnesses. By 2010 his medical bills reached nearly $30,000 and Maisy had to declare bankruptcy. Mental health parity regulations issued in 2010 prohibited separate day and visit limits on mental health care different from those applied to other covered benefits. Final regulations issued in 2013 also prohibit exclusions for treatment related to mental illness, such as attempted suicide.14

Safiya’s medical debt resulted when she reached the annual limit of coverage under her job-based health plan. Her employer, a fast food chain, provided a so-called “mini med” plan that limited coverage to just a few thousand dollars per year. When she found a breast lump and needed a biopsy, she quickly reached her plan limits and was left to pay $5,200 out-of-pocket. Another woman, Katherine, reached the lifetime limit on her policy in 2006 after she had been in extensive treatment for breast cancer. She spent several years trying to pay the non-covered medical bills, which totaled $35,000, but ultimately had to file for bankruptcy.

Sonya’s child was diagnosed with autism at age four. She said her family has “lived medical bills ever since.” She sought care from various specialists, speech therapists, and alternative medicine practitioners. In a number of cases treatments were simply not covered by her health plan provided through her husband’s large employer. Her medical bills for the autism treatment, in addition to those incurred by other family members, reached $60,000 over 16 years, leading her to file for bankruptcy.

Unaffordable Premiums

Two people we interviewed amassed substantial medical debt as a result of their non-group health insurance premiums.

One was Morgan, 51, a self-employed artist in Tennessee. Since 2005, he has been covered by a non-group policy he purchased for himself and his family. Initially he found both the premiums and cost-sharing affordable. But over the years, premiums increased steeply and Morgan tried to offset increases by raising the annual deductible. By 2009 his monthly premium for family coverage had reached $1,200 and his annual deductible was up to $5,000 per person. That year Morgan learned he had prostate cancer. Surgery was scheduled late in the year, so he had to satisfy two annual deductibles within a few months. He used credit card cash advances to pay the insurance premiums, but finance charges quickly inflated what he owed. They used nearly all of his retirement savings (about $10,000) to catch up, and then fell behind again. In mid-2010, he made the difficult decision to drop his wife from the policy, which cut the premium in half. By that time, though, their debts had reached $35,000. A few months later, the family filed for bankruptcy. Morgan describes his situation this way,

“Some people just drop coverage and go to the ER and pay nothing. But I was trying to do the right thing and stay insured. It’s so frustrating that I came close to ruining myself financially to do that. I spent thousands keeping my family insured. I have friends in Canada. They’re shocked to hear I pay more for health insurance than for my mortgage. It’s unnerving at times to look at the numbers. When I do my taxes and enter my health insurance costs, my tax software says ‘Are you sure? This seems high.’ Like a slap in the face. One year my health expenses were over $20,000 and my adjusted gross income was $25,000.”

Other Factors Unrelated to Insurance

Case studies revealed other factors that contributed significantly to medical debt. Serious illness can often be associated with a decline in income, making it harder for people to afford medical bills. In addition, people faced with serious illness were hampered in their ability to track medical expenses, challenge denials and correct mistakes, adding to what they owed. Finally, provider collections practices, as well as patients’ personal desire to pay their providers, led many people to rely on credit card financing or other drastic financial measures that had the effect of compounding their debt problems.

Income loss due to illness

In 18 of the 23 case studies, a significant reduction in household income resulted when the patient was too sick to work or a working family member had to quit or reduce hours to care for the patient. This frequently happens when a serious illness or injury occurs. For example, research finds that between 40 and 85 percent of cancer patients stop work during initial treatment, with absences ranging from 45 days to six months.15 Another study found that breast cancer survivors’ income fell on average by $3,600 five years after diagnosis; by contrast, a typical worker’s earnings increase over a five-year period, on average by $1,800.16 People interviewed for this report cited income loss as a key factor making it harder to afford the sudden onset of medical bills.

Kieran and Jenna’s struggled to pay more than $20,000 in medical bills from her illness and complicated pregnancy, and struggled even more when she had to quit her job due to illness. That cut the income for this family of six from $90,000 to $70,000 annually. Kieran emphasized what the loss of that second income meant. “With four kids, there’s always something – lunch money, something – and we couldn’t make it without her pay. Then when the medical bills started, things got out of control.” He took a part time job at CarMax and he and his son mowed lawns on weekends, but they had to cut back on a lot. “When my son broke his glasses, he had to wait a year before we could afford to get new ones. None of us went to the dentist for two years. We let one of the cars go.” Eventually Kieran and Jenna had to declare bankruptcy.

For Richard and his family, the income drop wasn’t as great, but the end result was similar. Richard suffered a traumatic leg fracture during a sporting event in 2007. At the time his $130,000 annual income provided a comfortable living for his family of four. But the leg injury required repeated surgeries, some with complications, and extensive physical therapy over the next four years. During extended treatments Richard had to go on short term disability, reducing his income to just $500 per week. He estimates he lost $12,000 in earnings in 2007, $6,000 in 2010, and almost $5,000 in 2012. Over those years, his medical bills reached $30,000, and he had to file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy. Under the court order, Richard must pay $1,000 per month to his creditors for five years.

Challenges to effective self-advocacy

Nearly all of those interviewed commented on the difficulty of managing medical bills. Most described the sheer number and frequency of bills and statements they received as “overwhelming.” Most also found bills and insurance statements were confusing or failed to provide sufficient information to describe a claim, what had been paid, what was still owed, and why. Several commented on how difficult it was to distinguish between new bills and repeated invoices for older, unpaid bills. Others observed that while the initial provider invoice would list and describe each billed service, subsequent invoices for unpaid balances usually didn’t itemize, instead just showing the total dollar amount owed.

Of those we interviewed, Stuart was one of the most meticulous in managing medical bills. His wife required several specialized surgeries over two years that had to be performed at a university hospital, 60 miles from their home. Between worrying about his wife and money and driving 120 miles per day, Stuart said managing the bills was a struggle. He described receiving multiple bills from the same provider. One bill, from a radiologist for a scan, appeared to be a duplicate of one Stuart had already paid so he set it aside. Only when he heard from a collections agent several months later did he realize the bill was for a separate scan. During that period, Stuart also needed a screening colonoscopy for himself. The ACA requires this screening service to be covered in full, but when the insurance statement came, the deductible had been incorrectly applied.17 When he called the insurer he was told it was his responsibility to work with his doctor to resubmit the claim with additional documentation in order for cost-sharing to be waived. Eventually Stuart got this sorted out, too, but with everything else going on it took effort. As he put it, “I’m a pretty easy going person, but I can understand how some people go postal over this stuff.” Stuart’s state operates a Consumer Assistance Program that will help residents resolve disputes and appeal denied claims, but he was not aware of this program.

Most others interviewed were not able to effectively track bills and resolve mistakes, including Gwen, who works in the health care industry and considers herself knowledgeable about health claims. But between caring for her frail husband and working full time as the sole breadwinner, she simply couldn’t manage. According to records Gwen provided, she received 125 different bills over a four-month period. Two claims were for ambulance transportation, one of which was denied. Gwen doesn’t know why. The insurance statement says non-emergency ambulance services are not covered, though an earlier ambulance claim was covered; it would appear the second claim was coded differently, but the statement doesn’t provide sufficient information to know for sure. Gwen could have appealed this denial, but didn’t pursue the matter. She also could have appealed her health plan’s decision to cover George’s inpatient rehab care out-of-network on the grounds that no other in-network facility was able to provide the level of care George needed, but she simply lacked the time and energy.

Studies show that consumers often don’t – or can’t – effectively resolve disputes with health plans or other payment errors. A Kaiser Family Foundation national survey of consumer experiences with health plans found a majority (51%) of insured, non-elderly adults reported some type of problem with their health plan, such as claims denials or difficulty obtaining referrals. Most consumers experiencing a problem had to try for a month or longer to fix it or they couldn’t satisfactorily resolve it at all.18 Especially when people are sick, managing insurance problems can be a challenge and many give up. Another study found that even when problems generated out-of-pocket costs to the patient of more than $1,000 or led to a serious decline in health, fewer than 40 percent of individuals complained to their health plan, and only rarely (3%) did they file complaints with state regulators.19 Consumers report they want and need help, but many don’t know where to turn. In the Kaiser survey, 89% of consumers didn’t know the agency that regulates health insurance in their state; 84% wanted an independent entity where they could seek help.

Medical debt collections

Most of the people we interviewed ended up in debt collections. Typically hospitals and other health care providers expected to be paid within 90 days of invoice. After that, it is common for unpaid bills to be referred to collections.20 Of the 23 people interviewed, 21 reported that at least some providers referred their debt to collections. Medical bills account for the majority of debts that are referred to third-party collection agents21 and for 17 percent of debts that are re-sold in the debt buying industry.22

Some bills may be referred to collections mistakenly. One study estimates that in 2010, 9.2 million Americans were contacted by a collections agency due to a billing mistake.23 Stuart was amazed at how quickly and automatically providers sent debts to collections. Though he had negotiated a payment plan with the hospital and had paid every installment on time, after 90 days the balance due was nonetheless referred to a collections agency. When he called the hospital to ask why, he was told it was an automatic practice and advised to ignore the collections notices and continue making payments directly to the hospital. Another bill that Stuart had paid in full was mistakenly sent to collections. It was up to Stuart to document the mistake in order to clear up this dispute.

For most we interviewed, being contacted by a debt collector was a new and unpleasant experience. A few people reported aggressive and harassing practices, such as late-night calls. Collections actions prompted many to take drastic steps to pay; sometimes these actions compounded their problems.

Credit card financing of medical debt

Most of those interviewed used credit cards to finance at least a portion of their medical debt. A 2007 study indicates that among low- and middle-income households with credit card debt, 29% report that medical expenses contribute to that debt. These so-called “medically indebted” individuals generally have much higher levels of credit card debt compared to consumers who have no medical bills on their credit card balances (“non-medically indebted.”) They are also twice as likely to have been called by bill collectors.

Charlene’s family became uninsured in 2009 when her husband lost his vision, job, and health benefits. The following year, their teenage daughter was hospitalized after an accident and in 2011, Charlene needed surgery. Hospital bills totaled $23,000. Though the hospital’s web site notes a charity care program, the only relief offered Charlene was a two-year payment plan with $800 monthly installments. When she said she couldn’t afford payments, the billing office urged her to pay with a credit card. She put several thousand dollars on the card, but then stopped when she saw how finance charges were adding to the total. Finally, Charlene took most of her retirement savings and emptied her daughter’s college fund to pay some of her debts.

Several others were encouraged to use special medical credit cards that can be used to pay bills for participating providers and that waive finance charges if bills are paid off within a specified period, such as 6-18 months.24 Other people elected to use credit cards on their own out of a sense of duty to pay providers who were caring for them. Still others relied on credit cards to finance day-to-day household expenses in order to free up cash to pay medical bills. In the end, however, most expressed regret over credit card financing because interest charges and late fees added significantly to what they owed.