The Rising Cost of Living Longer: Analysis of Medicare Spending by Age for Beneficiaries in Traditional Medicare

A companion article to this report, entitled “Medicare Per Capita Spending By Age And Service: New Data Highlights Oldest Beneficiaries” has been published in the journal Health Affairs.

In the context of ongoing discussions about the federal budget and national debt, policymakers, experts, and the media have called attention to the nation’s growing aging population and the implications for Medicare and the federal budget. At the same time, geriatricians and other providers who care for older patients are giving greater attention to the question of how best to meet the needs of an aging population. Between 2010 and 2050, the United States population ages 65 and older will nearly double, the population ages 80 and older will nearly triple, and the number of nonagenarians and centenarians—people in their 90s and 100s—will quadruple.1 The aging of the population has important implications for future Medicare spending because beneficiaries ages 80 and older account for a disproportionate share of Medicare expenditures. According to the Congressional Budget Office, population aging is expected to account for a larger share of spending growth on the nation’s major health care programs through 2039 than either “excess spending growth” or subsidies for the coverage expansions provided under the Affordable Care Act.2

To inform discussions about Medicare’s role in providing coverage for an aging population and to assess the relationship between Medicare spending and advancing age, this report takes an in-depth look at patterns of Medicare spending by age, overall and by type of service.3 Using the most current Medicare spending data available for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare in 2011 and trends since 2000, the analysis explores the following questions:

- To what extent does Medicare per capita spending rise with age among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, and at what age does per capita spending reach its peak before starting to decline?

- How does per capita spending for specific Medicare-covered services vary by age for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare over age 65, and how have these patterns changed over time?

- Has Medicare per capita spending for older beneficiaries (ages 80 and older) been increasing over time, after controlling for inflation?

- What is the pattern of per capita spending by age among decedents, and how does spending on decedents affect the pattern of per capita spending among traditional Medicare beneficiaries overall?

This analysis is based on data from a 5 percent sample of Medicare claims from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) from 2000 to 2011 (the most recent year available when this analysis was conducted) that includes all Medicare-covered claims for services covered under Parts A, B, and D. The analysis excludes beneficiaries who are age 65 because some of these beneficiaries are enrolled for less than a full year; therefore, a full year of Medicare spending data is not available for all people at this year of age. The analysis focuses on Medicare beneficiaries over age 65 rather than younger adults who qualify for Medicare because of a permanent disability to develop a better understanding of the relationship between Medicare spending and advancing age.

This study examines patterns of Medicare spending among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare rather than in Medicare Advantage plans because comparable data on Medicare spending by service are not available for this population (Medicare spending for Medicare Advantage enrollees takes the form of monthly capitation payments which are not based on actual service utilization4). Because we lack comparable data for the 25 percent of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2011, it is not possible to assess whether patterns of service use and spending in traditional Medicare apply to the Medicare population overall. More information about the data, methods, and limitations can be found in the Methodology.

Key Findings

Medicare Per Capita Spending By Age Among Traditional Medicare Beneficiaries Over Age 65 in 2011 and Trends, 2000-2011

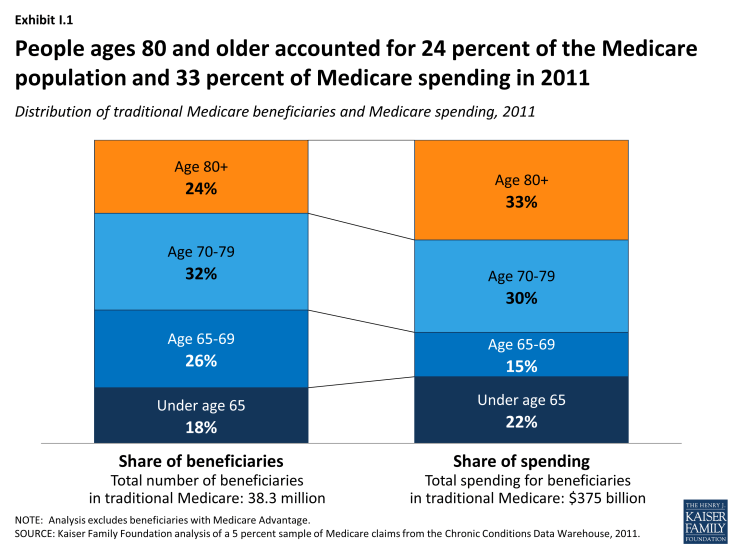

- Medicare’s octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians account for a disproportionate share of Medicare spending. In 2011, beneficiaries ages 80 and older comprised 24 percent of the traditional Medicare population, but 33 percent of total Medicare spending on this population (Exhibit I.1). In contrast, beneficiaries between the ages of 65 and 69 comprised 26 percent of the traditional Medicare population, but just 15 percent of total Medicare spending.

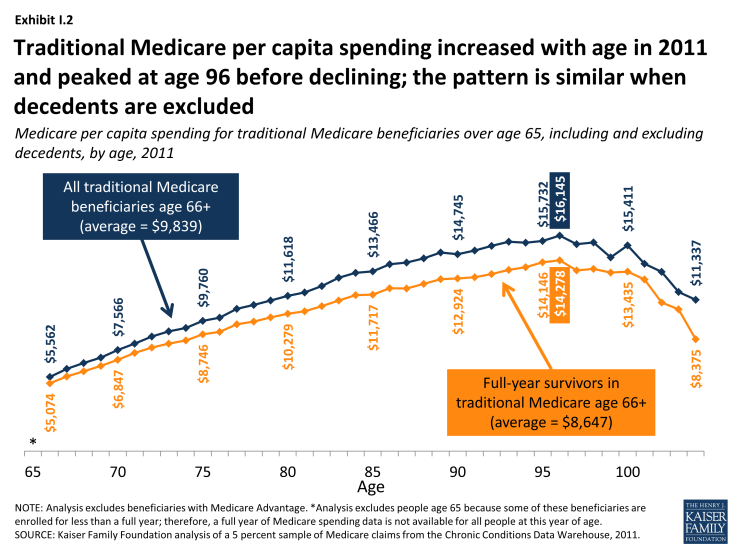

- In 2011, overall Medicare per capita spending increased with age, peaked at age 96, and then declined gradually for the relatively small number of beneficiaries at older ages (Exhibit I.2). Average Medicare per capita spending in 2011 more than doubled between age 70 ($7,566) and age 96 ($16,145).

Exhibit I.1: People ages 80 and older accounted for 24 percent of the Medicare population and 33 percent of Medicare spending in 2011

Exhibit I.2: Traditional Medicare per capita spending increased with age in 2011 and peaked at age 96 before declining; the pattern is similar when decedents are excluded

- The increase in Medicare per capita spending as beneficiaries age can be partially, but not completely, explained by the high cost of end-of-life care. Medicare per capita spending among survivors in 2011 (excluding beneficiaries who died during the year) also rises with age and peaks at age 96 ($14,278) before falling—but the averages are higher when decedents are included (Exhibit I.2).

- The pattern of Medicare per capita spending for beneficiaries who died in 2011 is markedly different; it declined steadily with age, falling from $43,000 among 70-year-olds to under $20,000 among centenarians. Yet because of higher death rates among older beneficiaries, average per capita spending among beneficiaries who die at older ages has a greater influence on the estimates of average spending among all beneficiaries at older ages.

- Between 2000 and 2011, Medicare per capita spending peaked at older ages, and was higher at the peak age in 2011 than in 2000, after controlling for inflation. Medicare per capita spending peaked at age 92 in 2000 ($9,557 in inflation-adjusted 2011 dollars), rising to age 96 by 2011 ($15,015 excluding Part D spending and $16,145 including Part D spending).

- Over time, the difference in Medicare per capita spending between beneficiaries ages 80 and older and younger beneficiaries has widened. In 2011, Medicare per capita spending was 2.5 times greater for 85-year-olds ($13,466) and 3 times greater for 95-year-olds ($15,732) than for 66-year-olds ($5,562).

- Between 2000 and 2011, Medicare per capita spending grew faster for beneficiaries ages 90 and older than for younger beneficiaries over age 65, both including and excluding spending on the Part D prescription drug benefit beginning in 2006. Including Part D spending, per capita spending grew at an average annual rate of 5.8 percent for beneficiaries ages 66 to 69 over these years, rising to 7.3 percent among beneficiaries ages 90 and older.

Patterns in Traditional Medicare Per Capita Spending for Selected Medicare-covered Services in 2011 and trends, 2000-2011

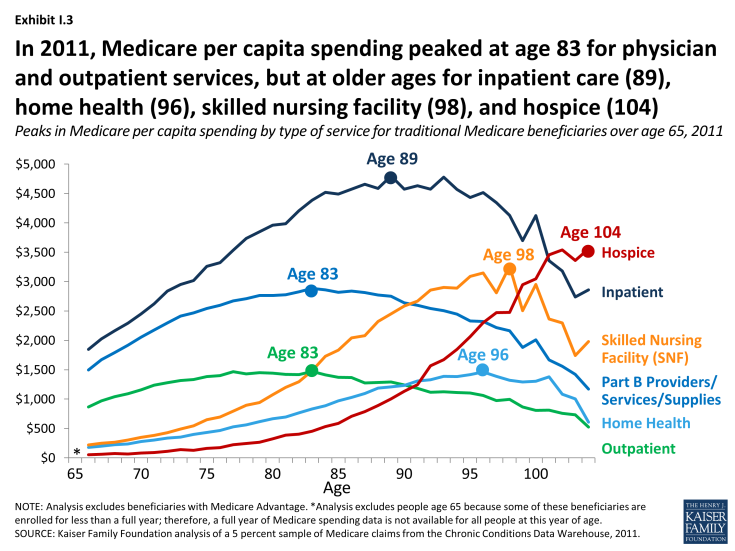

- The amount of average Medicare per capita spending on many Medicare-covered services in 2011 generally increased with age for beneficiaries in their 70s and 80s and then began to decline for older beneficiaries; the main exceptions were skilled nursing facility (SNF) and home health per capita spending, which increased for beneficiaries in their 90s before declining, and hospice spending which generally increased with age through the 90s and beyond (Exhibits I.2 and I.3). In contrast, per capita Part D drug spending was roughly constant among beneficiaries in their 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s.

Exhibit I.3: In 2011, Medicare per capita spending peaked at age 83 for physician and outpatient services, but at older ages for inpatient care (89), home health (96), skilled nursing facility (98), and hospice (104)

- In 2011, Medicare per capita spending on hospital inpatient services increased more than 2.5 times from $1,848 among 66-year-olds to $4,799 among 89-year-olds before declining among older beneficiaries. While per capita inpatient spending peaks at age 89, spending on inpatient care is relatively similar for beneficiaries between the ages of 84 and 97 (plateauing at around $4,500 per beneficiary).

- Despite a gradual reduction in Medicare per capita spending for Part B providers, services, and supplies for beneficiaries beginning in their mid to late 80s, per capita spending continues to climb into the mid-90s due to persistent levels of inpatient hospital spending and a sharp rise in skilled nursing facility and hospice spending in the late 80s and 90s. Between ages 86 and 96, Medicare per capita spending on skilled nursing facility services increased by more 50 percent (from $2,043 to $3,149) while per capita spending on hospice tripled (from $706 to $2,299).

- The relatively high per capita spending among beneficiaries in their mid-to late-90s in 2011 is influenced by skilled nursing facility (SNF), hospice, and (to a lesser extent) home health spending; excluding spending on these services, overall per capita spending peaks at age 89.

- Inpatient hospital care accounted for the largest share of per capita spending among traditional Medicare beneficiaries ages 66 and older in 2011, with the exception of centenarians for whom hospice spending comprised the largest share of their total Medicare per capita spending. As beneficiaries grow older, per capita spending on physician services accounts for a declining share of per capita costs.

Implications

This analysis shows Medicare per person spending rising steadily with age, more than doubling between ages 70 and 95 in 2011, and peaking at age 96, before declining for the relatively small number of beneficiaries at relatively older ages. The cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries who died in 2011 contributes to higher average per capita Medicare costs at all ages, but does not alter the pattern of per capita spending nor does it affect the peak age of Medicare spending in 2011. And over time, Medicare per capita spending has peaked at older ages, from age 92 in 2000 to age 96 in 2011, based on inflation-adjusted dollars.

As adults live into their 80s and beyond, they are more likely to live with multiple chronic conditions and functional limitations, and this combination (compared to having chronic conditions only) is associated with a greater likelihood of emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations as well as higher Medicare spending for inpatient hospital, skilled nursing facility, and home health services.5 Thus, it is not surprising that Medicare per capita spending is higher, on average, for older beneficiaries compared to those in their 60s and 70s. At the same time, the pattern of increasing per capita spending until beneficiaries are in their mid-90s raises questions as to whether beneficiaries are getting the appropriate mix of services as they age and whether more could be done to improve the management and delivery of medical care for aging Medicare beneficiaries.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) launched several payment and delivery system reforms that could alter patterns of care and spending for people on Medicare. Several of these initiatives aim to maintain or improve the quality of patient care and lower costs by reducing unnecessary care, managing care for high-need, “at risk” patients, and treating beneficiaries in the most appropriate (least cost) setting.6 The ACA also included provisions that aim to reduce unnecessary, preventable hospitalizations, better manage transitions following hospitalizations, and improve care management for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.7 Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced it would provide payments to physicians who manage care for beneficiaries with two or more chronic conditions.8 These efforts potentially could lower costs and improve care for Medicare patients, including the oldest old.

Consistent with other studies documenting higher costs for patients at the end of life, this analysis shows that Medicare per capita spending was nearly 4-times greater among beneficiaries who died in 2011, on average, than among those who lived the entire year. Yet the analysis also shows that Medicare per capita spending among decedents declines with age, suggesting that patients, families, and providers may be opting for less intensive and less costly end-of-life interventions for beneficiaries as they grow older. This possibility is consistent with the finding that average per capita spending on hospice services among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare increases with age, due to both a larger share of beneficiaries electing hospice at older ages and higher per capita hospice costs for older than younger Medicare beneficiaries who elect hospice care.

As the U.S. population ages, the increase in the number of people on Medicare and the aging of the Medicare population are expected to increase both total and per capita Medicare spending. The increase in per capita spending by age not only affects Medicare, but other payers as well. In fact, other studies have documented increases in both Medicaid and out-of-pocket spending by age, primarily attributable to the cost of long-term services and supports that are not covered by Medicare.9,10 Further work is needed to better understand the social, medical, and long-term care needs of older Americans and how best to address those needs. Focusing on ways to improve the management and coordination of care for high-need, high-cost patients, many of whom are among Medicare’s oldest beneficiaries, will be essential to meet the needs of an aging population.