How Much (More) Will Seniors Pay for a Doc Fix?

Unless Congress takes action prior to April 1, 2015, Medicare will be forced to cut the amount physicians are paid by 21 percent, the result of a payment formula known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) enacted as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. In all likelihood, the new Congress won’t let this cut happen. Lawmakers have passed stop-gap legislation 17 times to override the SGR, both to prevent physicians from seeing a drop in their Medicare payments and to guard against potential physician access problems for beneficiaries. None of these short-term “doc fixes” replaced the SGR outright.

Last year, Members of Congress in the House and Senate on both sides of the aisle came to consensus on a long-term alternative system for setting physician fees. This proposal, now back on the table, would give physicians a choice of receiving performance-based payments from Medicare or added payments if they participate in delivery models that account for both spending and quality. But, as in prior years, lawmakers have yet to come to agreement on the vexing issue of financing—and how to cover the federal cost of $175 billion over 10-years for this SGR replacement, as estimated by CBO. Among the more contentious issues is whether beneficiaries should pay more than they already would to help offset this cost to the federal government.

Medicare beneficiaries automatically contribute to the cost of repealing the SGR

Often overlooked in these discussions is the fact that, under current law, beneficiaries would automatically absorb their share of Part B costs associated with replacing the SGR. Take the Part B premium, for example, which, by design, is set to cover 25 percent of Part B spending. For every one dollar increase in Medicare Part B spending for physician and other Part B services, Medicare beneficiaries pay 25 cents in Part B premiums and Medicare pays the other 75 cents. In other words, both beneficiaries and Medicare would automatically incur costs that result from an SGR repeal—just as they have for previous SGR fixes.

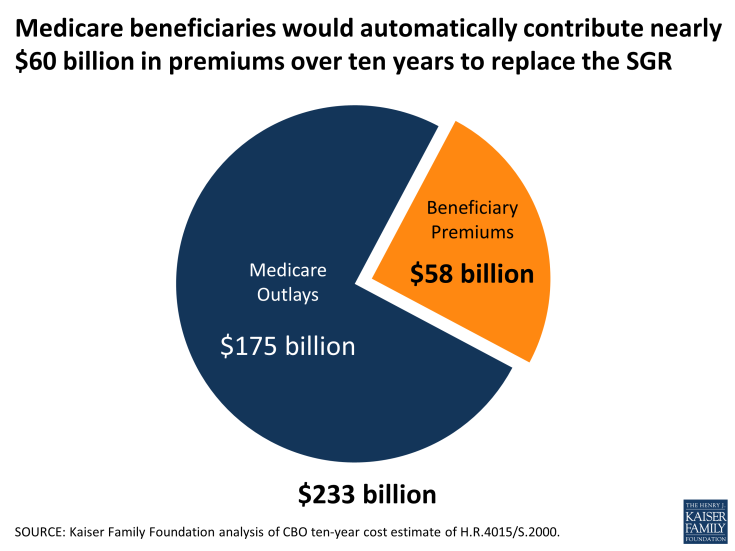

We estimate that Medicare beneficiaries would automatically contribute $58 billion dollars over the next ten years in Part B premiums to replace the SGR along the lines of the leading bipartisan proposal (Figure 1).1 This $58 billion is likely a conservative estimate of beneficiary out-of-pocket spending associated with the proposed SGR repeal because it does not take into account the effects on Part B deductibles and coinsurance payments in traditional Medicare. These beneficiary out-of-pocket costs come on top of the $175 billion in new costs to the federal government, making the combined true cost of replacing the old payment formula at least $233 billion.

Figure 1: Medicare beneficiaries would automatically contribute nearly $60 billion in premiums over ten years to replace the SGR

How Will Congress Offset the Budgetary Cost of the ‘Doc Fix’: Who Will Pay?

With strong interest in coming together to adopt the bipartisan alternative to the SGR, and finding a way to pay for it, one option under discussion would require beneficiaries to assume a portion of the $175 billion federal price tag, above what they will automatically pay in premiums and cost-sharing. Examples of proposals with a direct cost to current or future beneficiaries include those that would raise the Part B deductible and home health copayments for people just coming on to Medicare, adopt more income-relating of Medicare Part B and D premiums, and prohibit first-dollar supplemental Medigap coverage. Also on the table could be proposals to redesign Medicare’s deductibles and coinsurance (e.g., creating a single deductible and uniform coinsurance). The effects of these proposals on beneficiaries would depend on their health needs and financial circumstances.

Proposals to raise out-of-pocket costs for people on Medicare are controversial not only because seniors vote, but also because half of all people on Medicare live on incomes of about $23,500 or less and seniors spend 3-times more than younger households on health care, as a share of their household budgets.

Other ways to pay for the SGR replacement have also been floated, including proposals that would achieve Medicare savings by reducing Medicare payments to health care providers or health plans or negotiating lower prescription drug costs. In addition, some have proposed to look beyond Medicare for either savings or revenues, or strike a deal to fully or partially waive the pay-go budget requirements. At the risk of understating the case, none of these financing proposals is a slam-dunk.

Is SGR patch #18 on the horizon, or will a deal finally be struck?

With the clock now ticking, it remains unclear how or if lawmakers will come to agreement on financing, despite the bipartisan, bicameral consensus on an alternative payment system for physicians. This is the primary reason why Congress has been adopting short-term (cheaper) solutions, rather than a permanent fix. If financing were not an issue, the SGR would likely have been replaced a long time ago. In the absence of consensus on offsets, SGR patch #18 could be fast approaching. Or, just maybe, Congress will bypass the patch and produce the real deal.

Endnotes

To derive these estimates, we divided $175 billion (CBO’s cost estimate of 10-year outlays for H.R.4015/S.2000) by 75 percent (Medicare’s share of Part B spending) to calculate total new Medicare spending for the alternative physician payment system—$233 billion. Under current law, beneficiary premiums would cover 25 percent of total costs, or $58 billion over ten years. In 2015, as in prior years, Part B premiums have taken into account increases in Part B spending due to the SGR overrides. Therefore, in 2016 and future years, the actual increase in the monthly Part B premium is likely to be incremental relative to 2015 levels (but not relative to current law which would result in an actual reduction in Part B premiums – and potentially serious physician access problems). For example, according to the most recent Medicare Trustees report, the standard 2016 monthly Part B premiums are estimated to increase by $1.60,which assumes a fee-schedule update of 0.6 percent from 2015 (comparable to the 0.5 percent update in H.R. 4015/S.2000).