What Could a Medicaid Per Capita Cap Mean for Low-Income People on Medicare?

|

Key Take-Aways |

|

Policymakers are giving serious consideration to proposals, such as the American Health Care Act (AHCA),1 that would fundamentally change the structure and financing of Medicaid – the federal-state program that provides health coverage for 70 million low-income Americans, including one in five people on Medicare. Federal financing for Medicaid would be converted to a per capita cap model (such as under the AHCA) or block grant, both of which aim to limit and make more predictable federal spending on Medicaid and provide states more flexibility in their management of Medicaid spending. Such a change could affect low-income people on Medicare because Medicaid help cover Medicare’s premiums and cost-sharing, and pays for services not covered by Medicare, such as nursing home care.

Under current law, the federal government matches state Medicaid spending at a rate determined by a formula set in statute. Federal spending increases in response to the rise in the cost of providing care to enrollees, with no limit on total federal contributions.

In contrast, under a block grant or per capita cap model, federal Medicaid spending would rise at a specified growth rate, irrespective of the actual rise in Medicaid spending in a state. Limits on federal spending could put pressure on states to limit Medicaid spending over time, if Medicaid spending increased faster than the growth in federal contributions, potentially affecting 11 million seniors and people with disabilities on Medicare, who account for a disproportionate share of Medicaid spending.

This brief discusses the potential implications of Medicaid per capita cap or block grant proposals for low-income seniors and people with disabilities on Medicare. It also describes how the per capita cap model proposed in the AHCA could potentially affect low-income people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid. This brief will be updated as the bill is modified or other pieces of relevant legislation are introduced.

1. Why could the debate over Medicaid per capita caps or block grants matter for people who are covered by Medicare?

Medicare is a federal program that provides health insurance for 57 million people – 48 million seniors and 9 million younger adults with significant disabilities – but the Medicaid program makes Medicare affordable for the 11 million people on Medicare with very low incomes (6.5 million seniors and 4.6 million people under the age of 65 with significant disabilities). Medicaid pays Medicare premiums and cost-sharing for 8 million low-income people, and pays Medicare’s premiums (but not cost-sharing) for others. In addition, Medicaid provides benefits that are not covered by Medicare, such as nursing home care and home and community-based long-term care that would otherwise be unaffordable for seniors with low incomes. These benefits are specified under Title XIX of the Social Security Act (Medicaid) rather than Title XVIII (Medicare), which is why a change to Medicaid could affect low-income people on Medicare.

Low-income people on Medicare also receive assistance with premiums and out-of-pocket costs for prescription drug plans through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program; however, Part D LIS is financed by Medicare, rather than Medicaid and as a result would not be affected by a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant.

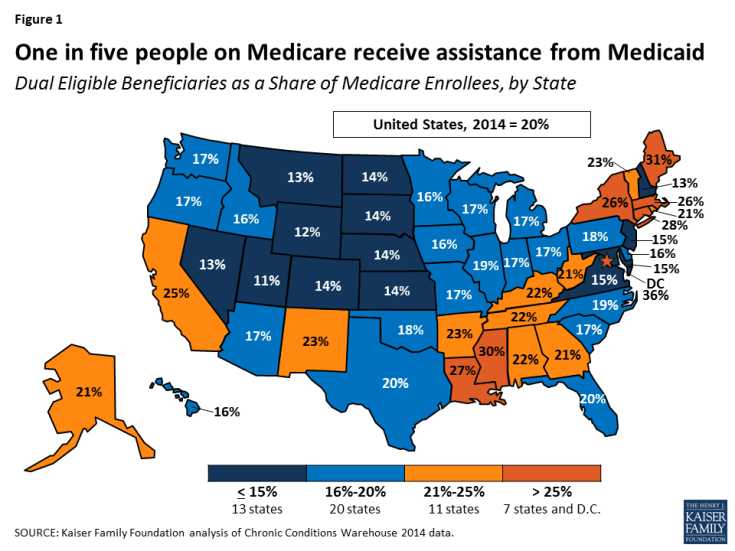

Low-income people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid comprise 15 percent of all people on Medicaid, ranging from 9 percent in Utah to 28 percent in Maine, and comprise 20 percent of all people on Medicare (Figure 1; Table 1). Federal and state Medicaid spending on low-income people on Medicare totaled $146.9 billion in 2011, most of which (62%) was for long-term care.

A structural change to Medicaid financing could have significant implications for low-income people on Medicare because Medicaid plays a major role in providing and financing benefits to low-income people that Medicare does not cover, and because the cost of their care accounts for a disproportionately large share of Medicaid spending. Most low-income people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid have incomes below the federal poverty level ($12,060 per year for an individual in 2017) and have little in savings or other assets, and for these people, Medicaid plays an important role in helping to make Medicare more affordable. For example, premiums for Medicare Part B ($121.80 per month) would comprise 12 percent of the income of someone living at the poverty line in 2017, and this amount does not include the cost-sharing that someone would incur for using Medicare-covered services or the costs of care not covered by Medicare, such as nursing home care.

2. What are the characteristics of people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid?

By definition, people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid have relatively low incomes, but they also differ from others on Medicare in their demographic composition, medical and long-term care needs, and service utilization. Women comprise the majority (60%) of all low-income people on Medicare who receive additional assistance from Medicaid (Table 2). Medicaid also plays an important role for people on Medicare who are younger than age 65 and have a significant disability: half of Medicare’s under-age 65 population receives assistance from Medicaid. While most people with both Medicare and Medicaid are seniors, about four in ten are under age 65 and qualified for Medicare because of a disability in 2012.

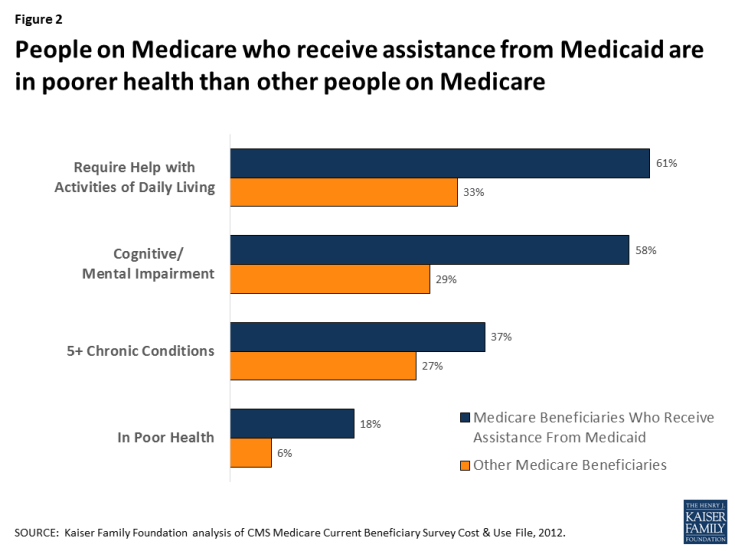

Low-income people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid tend to have more chronic conditions, cognitive limitations and functional limitations than others on Medicare: about six in ten (61%) need assistance with one or more activities of daily living (versus 33% of other people on Medicare), more than half (58%) have a mental condition or cognitive impairment (versus 29%), one-third (37%) have five or more chronic conditions (versus 27%), and about one in six (18%) rate their health status as poor, more than three times the rate among other people on Medicare (6%; Figure 2).

Figure 2: People on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid are in poorer health than other people on Medicare

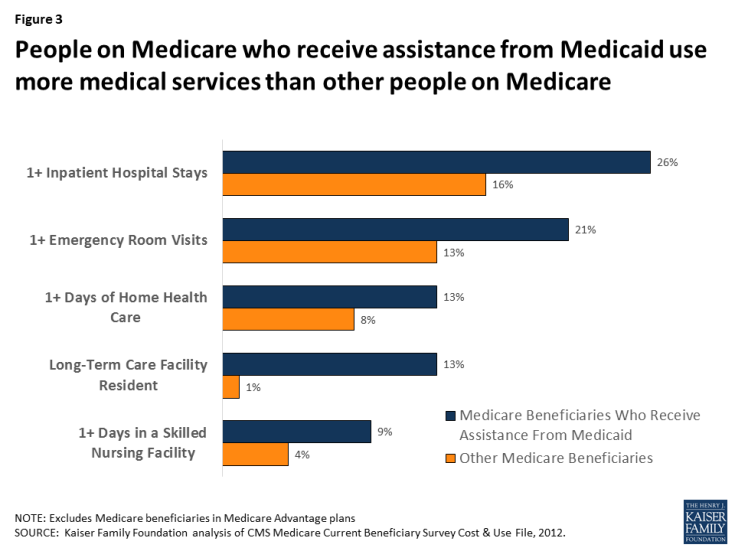

As a result of having greater medical, functional, and cognitive needs, low-income people with both Medicare and Medicaid also use more health care services than others on Medicare, including hospital stays, emergency rooms, home health care and skilled nursing facility stays (Figure 3). With relatively high rates of cognitive and physical limitations, it is not surprising that a substantially larger share of low-income people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid live in a facility, such as a nursing home or mental health facility (13% versus 1% of other people on Medicare).

Figure 3: People on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid use more medical services than other people on Medicare

3. How does the federal government help to finance Medicaid under current law?

The Medicaid program is jointly financed by the federal government and states. State spending for eligible beneficiaries and qualifying services is matched by the federal government. The federal share of Medicaid is determined by a formula set in statute, and is structured so that the federal government pays a larger share of program costs in poorer states. The formula for federal contributions, known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), results in federal contributions that range from 50 percent to 74 percent in 2017.

Under current law, federal contributions increase with the number of people covered and the rise in enrollees’ health and long-term care costs. The federal government pays more for sicker people with higher health care costs and pays less for healthier people with lower health care costs, as it does with Medicare. The federal contributions under Medicaid follow state spending and are not capped annually or per person.

4. How would a per capita cap or block grant change federal financing of Medicaid for low-income people on Medicare?

The idea behind converting Medicaid to a per capita cap or block grant would be to make federal spending for Medicaid more predictable while providing states more flexibility in their management of Medicaid spending. With a Medicaid per capita cap, such as that proposed in the American Health Care Act (AHCA), the federal government would provide states a fixed amount per Medicaid enrollee, with no limit on the number of people who can enroll in each state’s Medicaid program. The amount provided by the federal government would be the same amount for each person in a category, irrespective of the person’s actual health care costs, and would be based on the state’s average per capita spending for people in that category in the base year, growing at a specified rate over time.

Under a Medicaid block grant, the federal government would provide states a fixed amount that would not vary by the number of Medicaid enrollees. Unlike a per capita cap, federal funding for Medicaid under a block grant would not be based on enrollment. However, similar to a per capita cap, federal funding under a block grant would not vary with the health needs or actual costs of the individuals enrolled in states’ Medicaid programs, and it would be based on average spending in a base year and grow at a specified rate over time. Importantly, under the AHCA, as amended, states would have the option of receiving a block grant for certain populations, but not for the elderly, blind and disabled.

The AHCA would change federal funding for Medicaid financing to a per capita cap model. Enrollees would be divided into five categories, with separate allotments for each category: elderly (65+), blind and disabled, children, adults who gained Medicaid coverage as a result of the state’s Medicaid expansion under the ACA, and non-expansion adults. Each state’s average per person spending in fiscal year 2016 would serve as the base year and would be trended forward to 2019 by the medical care component of the consumer price index (CPI-M). In future years, the annual per capita allotment would be inflated by CPI-M+1 for the elderly, and blind/disabled populations and by CPI-M for other Medicaid populations.

Federal financing for virtually all Medicaid benefits, including nursing home care, would be included in the allotment under the AHCA, but financing for assistance with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing provided by Medicaid to low-income people on Medicare would appear to continue to be provided as under current law and would not be included in the per capita allotment. Congress is seeking to pass the AHCA through budget reconciliation, which requires any change to have a budgetary impact. The bill does not include changes to mandatory Medicaid benefits and coverage groups; such a change might not be allowable under budget reconciliation rules if it did not have a direct impact on the federal budget. However, it is possible that the Secretary of Health and Human Services could use his authority to provide states more latitude.2,3,4

5. Why might states consider reducing Medicaid spending for low-income people on Medicare?

A potential concern with per capita caps and block grants is that federal funding may not keep pace with state Medicaid programs’ growth in health care costs. If this concern is borne out, states might feel pressure to consider options for reducing Medicaid spending for seniors and younger people on Medicare with disabilities who account for a disproportionately large share of Medicaid spending. Although low-income people on Medicare accounted for just 15 percent of the Medicaid population, they accounted for 33 percent of Medicaid spending in 2012.5

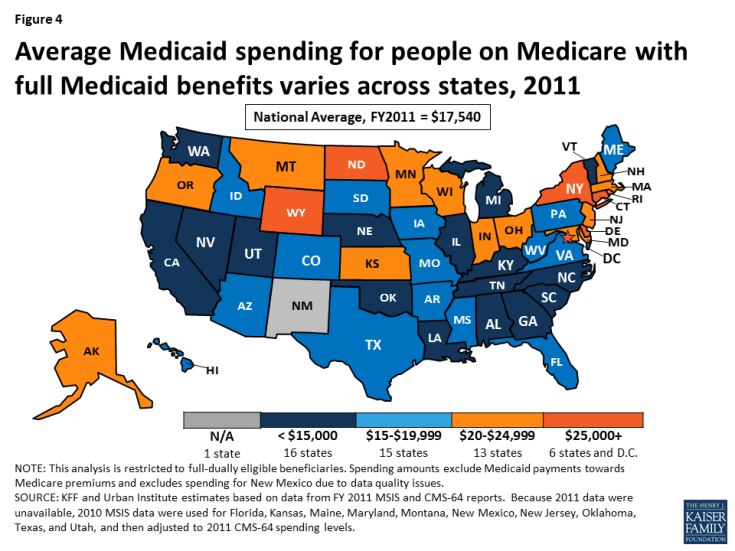

On a per person basis, Medicaid spent $17,540 on each person on Medicare who receives full Medicaid benefits (excluding amounts spent on Medicare premiums), on average, in fiscal year 2011 (Table 3). For about half of the people with both Medicare and Medicaid, Medicaid spent less than $4,000 per person but Medicaid spending exceeded $40,000 per person for 15 percent of the low-income people on Medicare.

Federal funding under a per capita cap model, such as that in the AHCA, would provide allotments based on states’ average Medicaid spending in the base year, which in 2011, ranged from a low of $10,607 (SC) to $32,051 (WY) for people on Medicare (Figure 4; Table 3). However, a per capita cap model would also lock-in variation in spending across states that may or may not persist in the future. States that are able to reduce their average Medicaid expenditures over time for seniors and younger adults with disabilities may be able to achieve savings under the per capita cap approach, while states that already adopted strategies to reduce average spending per enrollee may have fewer opportunities to achieve savings in the future. Additionally, states that incur higher average costs over time due, for example, to a rapidly aging population, may need to find other sources of revenue or reduce costs under a per capita cap model, possibly by reducing provider payments or eliminating coverage for optional services or populations.

Figure 4: About one-quarter of low-income people on Medicare receiving assistance from Medicaid are in Medicare Advantage plans

6. What potential changes could states make under a per capita cap or block grant that could affect low-income people on Medicare?

The possible effects of Medicaid per capita cap or block grant proposals on low-income people on Medicare would vary depending on the details of the proposal. States could, for example, decide to scale-back or eliminate optional services, such as dental care, vision care, and home and community-based services (HCBS), just as they can under current law in the absence of a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant. While some proposals would explicitly require states to maintain coverage of mandatory services, such as nursing home care, other proposals would provide states more flexibility with regard to which services to cover. The AHCA would not change the services that states are required to cover for seniors and people with disabilities. Such a change to mandatory services might not be allowable under budget reconciliation rules if it did not have a direct impact on the federal budget.6,7,8

In addition to scaling back optional benefits, states could restrict the eligibility criteria for populations that they are not required to cover. Under current law, states are required to provide Medicaid assistance to all who qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or the Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs),9 and have the option to also provide coverage to other groups of people with low-incomes, which many states have opted to do. For example, in 2015, 44 states covered people who need long-term care and have incomes up to 300 percent of the SSI level (225% of the federal poverty level) through the special income rule. To reduce state Medicaid spending, these states could opt to not cover these optional populations, which would result in fewer people qualifying for Medicaid long-term care coverage.

The AHCA would appear to retain current law financing for Medicare premiums and cost-sharing assistance, with the federal government providing matching funds under the current formula for this assistance. This separate financing structure provides less of a financial incentive for states to scale back premium or cost-sharing assistance relative to other proposals that would incorporate these benefits into a per capita cap or block grant. If states pared back these benefits, people with low-incomes could have difficulty affording Medicare.

7. How could a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant affect federal spending on Medicare?

A Medicaid per capita cap or block grant would not directly affect federal Medicare spending for low-income people on Medicare, which totaled $187 billion in 2012.10 Low-income people on Medicare would still be entitled to all services covered under Medicare Parts A and B, as well as prescription drug coverage under Medicare Part D, including assistance under the Part D LIS program.

However, a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant could have ripple effects that indirectly affect low-income people’s use of Medicare-covered services and Medicare spending, if federal funding for Medicaid does not keep pace with health care costs, or states look to reduce spending for other reasons. If states scaled back optional benefits, or tightened eligibility for optional populations, costs could be shifted to low-income seniors and people with significant disabilities. Similarly, if states reduced cost-sharing assistance by tightening eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs, for example, then low-income people on Medicare who no longer qualify for cost-sharing assistance might go without needed care or postpone treatment due to cost concerns.

Given their low-incomes, people with both Medicare and Medicaid may not be able to shoulder these costs and instead forgo needed care or postpone treatments. Higher cost-sharing requirements for low-income people, in the short-term, could lead to reductions in service utilization and lower Medicare spending, but could also result in higher rates of preventable hospitalizations and emergency room visits down the road – expensive services covered by Medicare.

Additionally, if more people become uninsured prior to going on Medicare as a result of changes made to Medicaid, Medicare spending could rise. Research has shown that people who are uninsured prior to going on Medicare use more health care services and incur higher Medicare spending once they are on Medicare, than if they had health insurance before going onto Medicare.11

8. How could a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant affect providers that serve people with both Medicare and Medicaid?

It is not clear how Medicaid payments to health care providers on behalf of low-income people on Medicare would change under a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant. Under a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant, states could be under financial pressure to reduce provider payment rates, to the extent that they able to do so, if federal funding for Medicaid does not keep pace with health care cost growth or states otherwise need to reduce Medicaid spending. Reductions in provider payment rates could directly affect the providers that treat low-income people on Medicare who receive assistance from Medicaid, particularly nursing homes and other providers of long-term services and supports for whom Medicaid is a primary source of revenue.

Reductions in payment rates could also affect providers who accept Medicaid payments as cost-sharing for Medicare services, including hospitals, physicians, health centers, and clinics. Today, many states pay less to providers than the total amount of due for Medicare cost-sharing since states are only required to pay the amount that would have been paid if Medicaid covered the service instead of Medicare, and Medicaid payments to providers are often lower than Medicare payments.

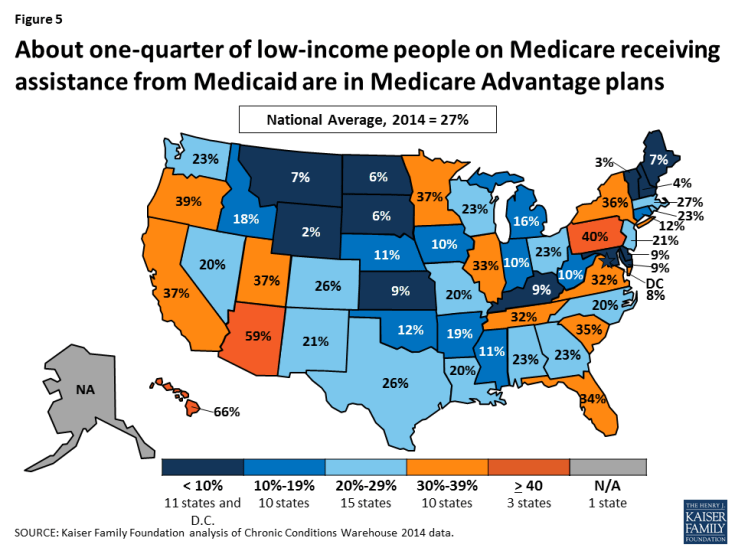

9. How could a Medicare per capita cap or block grant affect Medicare private plans and people enrolled in the plans?

A Medicaid per capita cap or block grant could potentially affect Medicare Advantage plans that, as of 2014, provided benefits to as many as 3 million low-income people on Medicare who were also covered by Medicaid (Figure 5). This includes 2.3 million enrollees who receive assistance from Medicaid with premiums only and 0.7 million who are eligible for cost-sharing assistance and other Medicaid benefits. Similarly, a per capita cap or block grant could affect Medicare Part D drug plans and their enrollees.

Figure 5: About one-quarter of low-income people on Medicare receiving assistance from Medicaid are in Medicare Advantage plans

If states under fiscal pressure respond by reducing the number of people on Medicare who would be eligible for Medicaid assistance, then federal payments to Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D drug plans could decline. The capitated payments received by Medicare Advantage and Part D plans under current law are adjusted for the health status of the plans’ enrollees, with an automatic bump up in payments for enrollees who qualify for assistance from Medicaid. This payment bump is intended to help compensate plans for these enrollees’ typically higher than average Medicare spending, and higher spending than can be explained by their health conditions. If fewer Medicare Advantage and Part D enrollees were eligible for Medicaid, then plans would not receive the increase in payments for these enrollees, which would reduce federal payments to plans and could weaken the incentives for plans to enroll low-income people.

10. How could the effect of a per capita cap or block grant for low-income people on Medicare vary across states?

If federal payments to states for Medicaid are modified through a per capita cap or block grant, some states could face greater challenges than others in meeting the needs of an aging population, depending on state changes in demographics, population needs, and the growth in health and long-term care costs. Neither a per capita cap nor block grant model would take into account changes in the specific health and long-term care needs of a given state’s population. As a consequence, both models would likely have different effects across states.

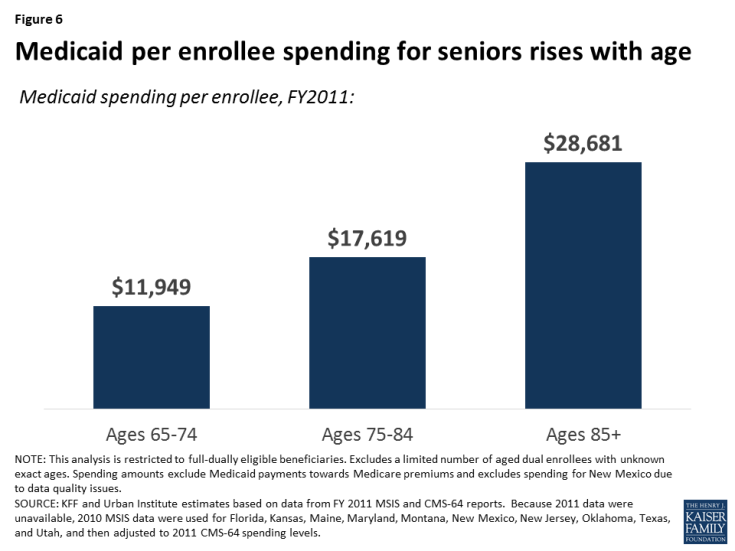

The impact on a given state could depend on a number of factors, including changes in the demographics and mix of high-cost versus low-cost enrollees since the per enrollee payment would be based on average costs in the base year. For example, under either a Medicaid per capita cap or block grant model, states with a growing share of high-cost enrollees (e.g., nursing home residents) could face more fiscal pressure than states with relatively low average costs, and the former states may need to find other funds to maintain benefits or reduce Medicaid spending if they have trouble covering their Medicaid costs. The aging of seniors on Medicaid, in particular, could affect how states fare under a per capita cap or block grant because average Medicaid costs rise with age – with costs for seniors ages 85 and older more than two-times larger than for younger seniors between the ages of 65 and 74, on average (Figure 6).

The impact of a block grant or per capita cap would also depend on underlying costs drivers that may vary across states. For example, states that experience a relatively rapid increase in labor costs (e.g., for nurses and home care workers) may have greater difficulty absorbing costs than other states, if federal contributions are capped. The effect for any given state would also vary with the growth in average health care and long-term care costs per person, and states in which Medicaid costs grow relatively rapidly would be more challenged than other states to find the resources to care for their residents.

This issue brief was funded in part by The Retirement Research Foundation.