Medigap Reform: Setting the Context for Understanding Recent Proposals

Introduction

In recent years, policymakers have focused on a wide range of options to inform the national debt reduction debate, including proposals to help reduce Medicare spending by reforming the current Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap) market. Due to Medicare’s relatively high cost-sharing requirements, the vast majority of beneficiaries have some source of coverage that supplements Medicare, including 9 million Medicare beneficiaries who purchase Medigap policies. Some beneficiaries with Medigap policies also have other sources of supplemental coverage, including coverage from employer or union-sponsored retiree health plans, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or Medicare Advantage plans.

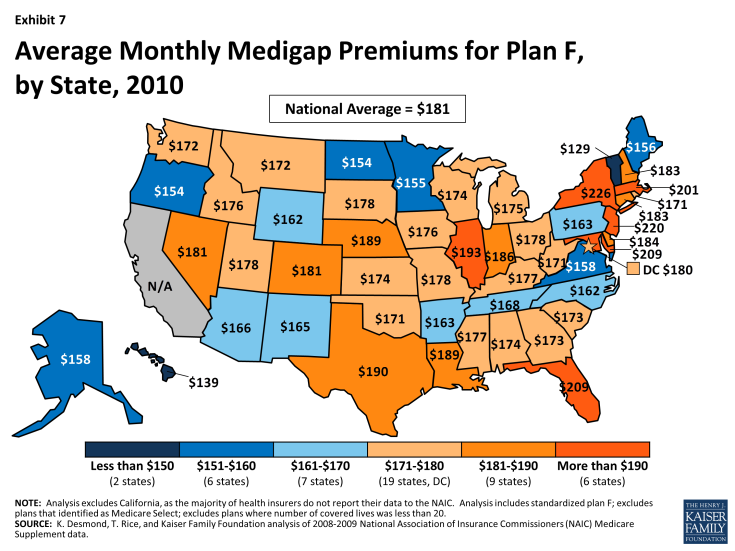

Nationwide, nearly one in four of all Medicare beneficiaries had a Medigap policy in 2010, including beneficiaries with multiple sources of supplemental coverage (Exhibit 1). Among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare (excluding people in Medicare Advantage), more than one in four (26%) has a Medigap policy.1 In some states, enrollment is much higher than the national average. As described later in the brief, about half of all beneficiaries in five states had a Medigap policy (IA, KS, ND, NE, and SD). Most Medigap enrollees (86%) live on incomes below $40,000 per person, and nearly half (47%) have incomes below $20,000 per person.

Exhibit 1. Nearly one in four Medicare beneficiaries had a Medigap policy as a supplemental source of coverage in 2010

This issue brief contextualizes recent proposals to change Medigap plans in order to understand how they may affect Medicare beneficiaries, using recently available data. The brief begins with an overview of Medigap’s role in providing supplemental coverage for Medicare beneficiaries. It then presents the most current data available on Medigap enrollment and premiums, by state, beneficiary characteristic, and plan type,2 and describes recent Medigap proposals that have emerged as part of efforts to reduce Medicare spending.

Medigap’s Role for Beneficiaries

Medicare provides broad protection against the costs of many health care services, but has relatively high cost-sharing requirements and significant gaps in coverage. Traditional Medicare has deductibles for Parts A (inpatient) and B (physician and outpatient) services, 20 percent coinsurance for most Part B services, coinsurance for inpatient hospital and skilled nursing facility stays exceeding 20 days, and no maximum on the amount beneficiaries could incur in out-of-pocket costs each year (Table A1). As a result, most beneficiaries covered under traditional Medicare have some form of supplemental coverage to help cover cost-sharing expenses required for Medicare-covered services.

Since the early years of the Medicare program, a substantial share of the Medicare population has relied on Medigap to help with Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements. Medigap enrollees tend to include beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who do not have access to an employer or union-sponsored retiree health plan and beneficiaries who are not poor enough to qualify for Medicaid. Medigap policies have helped to shield beneficiaries from sudden, out-of-pocket costs resulting from an unpredictable medical event, and have allowed beneficiaries to more accurately budget their health care expenses, which is important to a population living on fixed incomes. Because Medicare and private Medigap insurers generally coordinate payments to providers, Medigap also minimizes the paperwork burden for beneficiaries. In most cases, there are no claims to check or bills to pay. Even with Medigap, beneficiaries often incur significant out-of-pocket expenses for services that are not covered by Medicare (such as dental and long-term care) and for costs associated with prescription drug coverage offered separately by Part D plans.

The structure of Medigap policies has become more uniform and regulated over the years to help beneficiaries more easily compare policies and to address concerns about the marketing and quality of Medigap policies. Several laws since the 1970s – and in particular, the Social Security Disability Amendments of 1980 (also referred to as the “Baucus Amendments”) and the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1990 – changed the requirements and standards for Medigap policies, including standardizing benefits, limiting the duration of exclusions for pre-existing conditions, and requiring minimum medical loss ratios.3,4 As a result, today Medicare beneficiaries can enroll in one of 10 plan types, and all plans of the same letter are required to offer the same benefit package, facilitating an “apples-to-apples” comparison (Table A2).5 Two Medigap plans – C and F – cover both the Part A and the Part B deductible, thus providing “first-dollar” coverage for all Medicare-covered services.6

Enrollment in Medigap Plans

Enrollment in Medigap has been relatively stable since 2006, despite the rising enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans during this time frame.7 In 2010, nearly one in four (23%) Medicare beneficiaries nationwide had a Medigap policy.8 Beneficiary characteristics are drawn from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Cost and Use File and plan enrollment is from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC).

All Medigap Plans

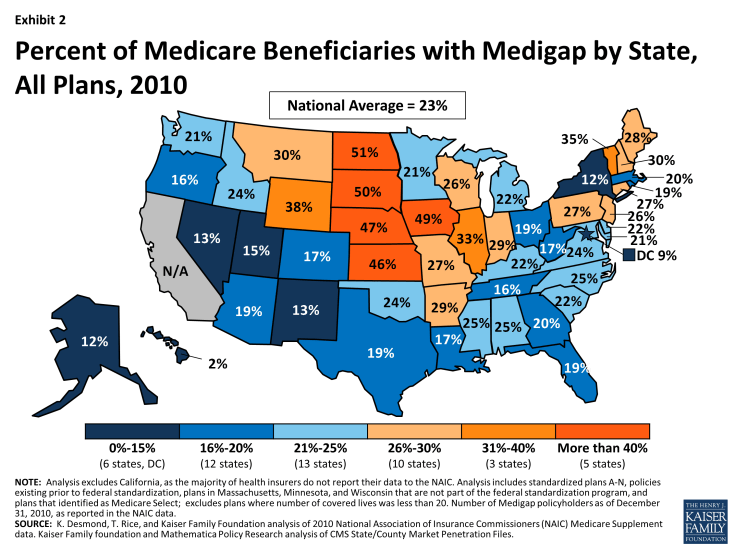

- The share of beneficiaries with a Medigap policy varies across states, ranging from 2 percent of beneficiaries in Hawaii to half of all beneficiaries in North Dakota (Exhibit 2; Table A3). Penetration was highest in the Midwest and Plains states; nearly half of all beneficiaries in five states had a Medigap policy to supplement Medicare in 2010 (IA, KS, ND, NE, and SD). A larger share of beneficiaries who purchase Medigap policies than others on Medicare live in rural areas (28% versus 23%) and are in relatively good health (82% versus 73%).

- About 4 million beneficiaries with a Medigap policy also have other forms of supplemental coverage, including more than 2 million with employer-sponsored coverage (Exhibit 1).

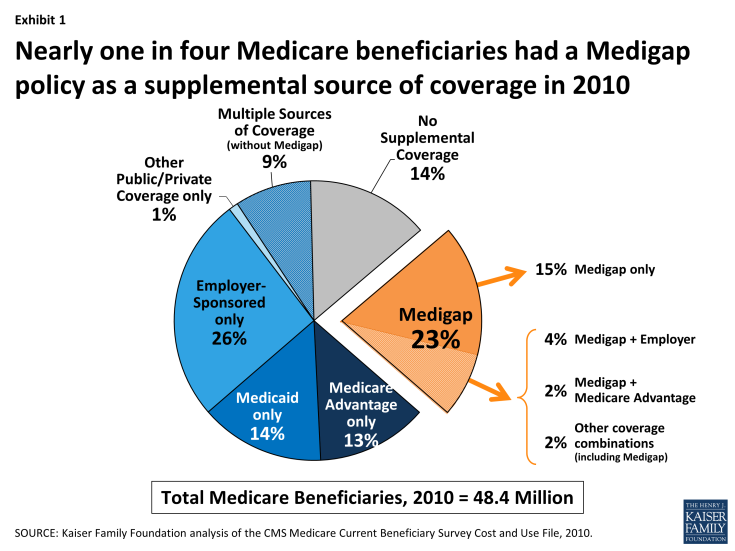

- The vast majority of individuals with Medigap (86%) have incomes below $40,000, and nearly half (47%) have incomes below $20,000 (Exhibit 3). A smaller share of Medigap policyholders than beneficiaries with employer-sponsored coverage have incomes above $40,000 and a smaller share of Medigap policyholders than beneficiaries with Medicaid have incomes below $20,000.

Exhibit 3. Distribution of Income of Medicare Beneficiaries, by Source of Supplemental Coverage, 2010

- Younger Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities are less likely than seniors to have Medigap because federal law does not require insurance companies to offer Medigap plans to disabled beneficiaries and because many beneficiaries who are under the age of 65 and disabled qualify for Medicaid to supplement Medicare; however, some states have open enrollment periods with guaranteed issue requirements for beneficiaries under the age of 65 with disabilities.9

Medigap Plans with First-Dollar Coverage

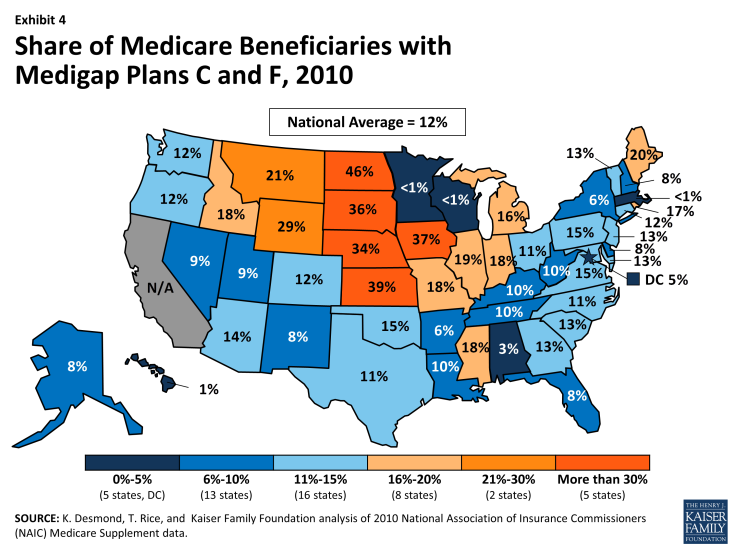

- Nationwide, about 12 percent of Medicare beneficiaries had plans C or F in 2010, plans with first-dollar coverage that covers both the Part A and Part B deductibles. The share of Medicare beneficiaries with Medigap plans C or F varies greatly by state (Exhibit 4). In 5 states, more than one-third of Medicare beneficiaries had Medigap plans C or F (IA, KS, ND, NE and SD), while in 4 states, less than 2 percent of beneficiaries had Medigap plans C or F (HI, MA, MN and WI).10

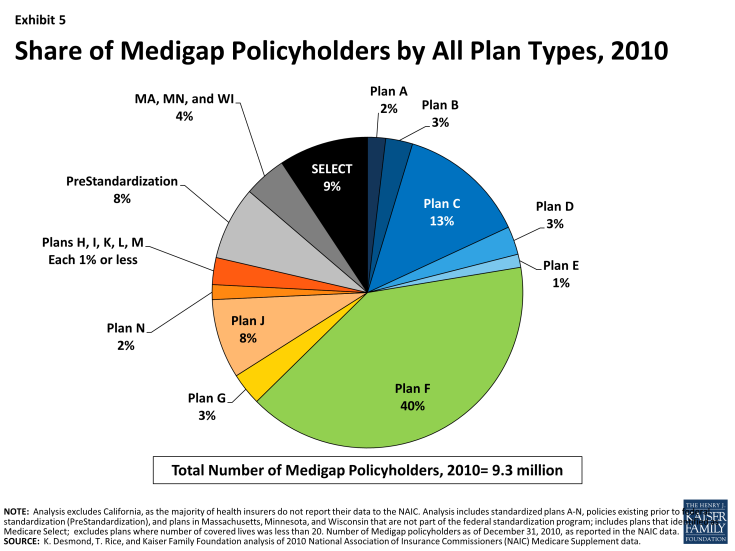

- The majority of people with Medigap (54%) had first-dollar coverage with either plan C or plan F in 2010 (13% and 40%, respectively; Exhibit 5). A small share (8%) of people with Medigap were in pre-standardized plans that were issued prior to the federal standardization of Medigap in 1992. Another eight percent are in plan J, which is no longer available to new policyholders and included prescription drug coverage prior to the inception of the Medicare Part D prescription drug program in 2006. Plans M and N, established in June 2010, had more than 144,000 policyholders by the end of 2010.

- The share of Medigap policyholders with plans C or F varies by state (Table A3). In 26 states, more than half of the people with Medigap had plan F. In another two states, Rhode Island and Michigan, more than half of the people with Medigap had plan C.

Premiums for Medigap plans

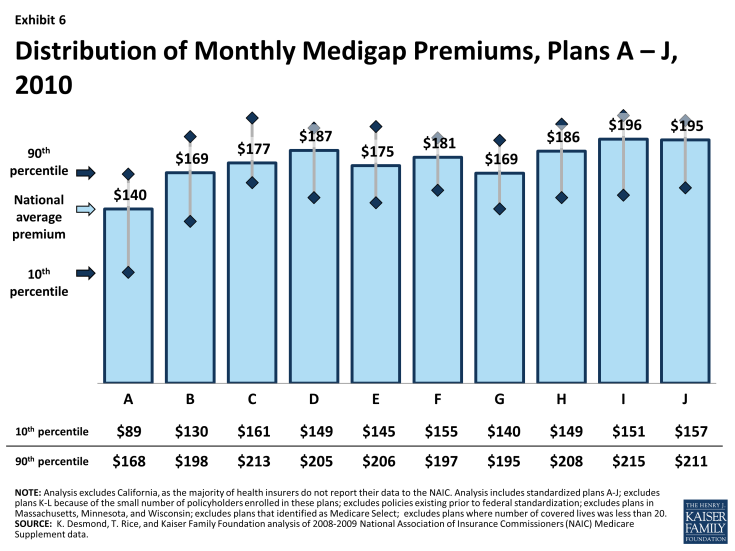

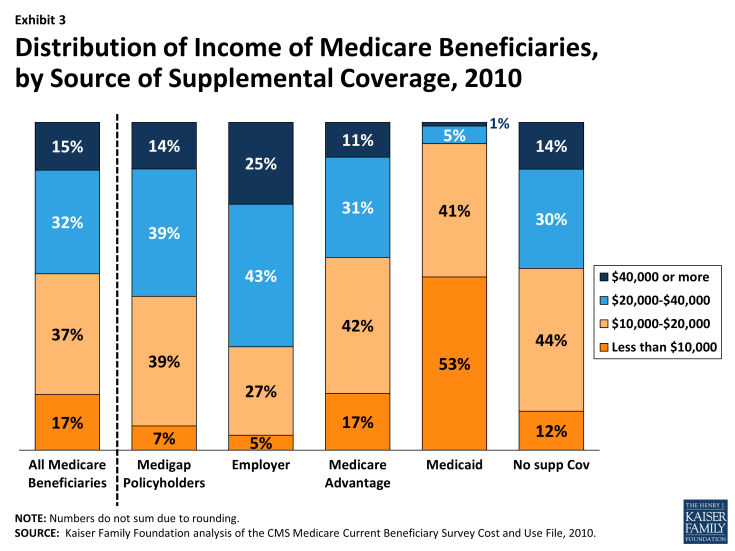

Beneficiaries with Medigap generally pay a monthly premium for their coverage, in addition to their Medicare premiums (Part B and D).11 People with Medigap paid an average of $183 per month in premiums for their policy in 2010, with wide variations across states and by plan type (Table A3). Even when ignoring the least expensive (in the bottom decile) and most expensive (in the top decile) states, average premiums can vary by as much as $79 per month across states for the same plan, despite a standardized benefit package (Exhibit 6). For example, the average plan F premium across all states is $181 per month. Average plan F premiums range from a low of $129 per month in Vermont, to a high of $226 per month in neighboring New York (Exhibit 7); both Vermont and New York require premiums to be community rated, indicating that states’ rating rules do not seem to exclusively determine whether states’ average premiums are relatively low or high.12 In 80 percent of states, the average monthly premium for plan F was between $155 and $197. Similarly, average plan C premiums nationwide are $177 per month, and in most states, the average monthly premium for Plan C was between $161 and $213 (Table A3).

Overview of Recent Proposals to Modify Medigap Coverage

Various proposals and recommendations have emerged in recent years that would restrict, limit and/or penalize Medigap coverage, generally in the context of broader proposals to reduce federal spending (Table 1).13 These proposals and recommendations to change Medigap coverage are often motivated by several studies that find most Medicare beneficiaries with Medigap use more Medicare-covered services and incur higher Medicare costs than beneficiaries without supplemental coverage.14 For example, a study from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) showed that spending for Medicare beneficiaries with Medigap policies was 33 percent higher than for beneficiaries without supplemental coverage.15 Researchers have also found that health care spending grew at a faster rate for beneficiaries with Medigap than for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare with no supplemental coverage.16 These studies are consistent with numerous studies that show individuals use fewer services – both necessary and unnecessary – when confronted with larger cost-sharing requirements.17

Prohibiting first-dollar Medigap coverage is therefore projected to reduce total Medicare spending and beneficiary spending, because exposure to higher cost-sharing requirements would lead enrollees to use fewer health care services.18 Requiring beneficiaries to pay higher cost-sharing, however, could also lead to higher aggregate spending over the long term for some vulnerable subpopulations, such as the chronically ill, beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and low-income seniors, if they forgo necessary services as a result, and use more high-cost, acute care services in the future.19

Many proposals and recommendations would prohibit Medigap plans from providing first-dollar coverage by requiring plans to include deductibles for Part A and Part B services. Such proposals are designed to discourage utilization (and reduce spending) by exposing beneficiaries to greater costs when they seek medical care. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated in its 2013 report Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2014 to 2023 that barring Medigap policies from paying the first $550 in cost-sharing liability and limiting coverage to 50 percent of the next $4,950 in out-of-pocket costs could achieve $58 billion in savings from 2015 to 2023.20 Under this approach, beneficiaries with Medigap could be expected to use fewer Medicare-covered services due to higher cost-sharing requirements, which would lead to a decrease in both average Medigap premiums and Medicare Part B premiums. Analyses have found that most Medicare beneficiaries with Medigap policies would be expected to pay less for their health care overall, but enrollees in relatively poor health would be more likely to face higher overall health care costs.21

Other proposals would apply a premium surcharge (or excise tax) on Medigap premiums. For example, President Obama’s budget for fiscal year (FY) 2014 proposed applying a surcharge on Part B premiums that would be equivalent to about 15 percent of the average Medigap premium on new beneficiaries that purchase Medigap policies with “particularly low cost-sharing requirements,” beginning in 2017.22 The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) estimated that this proposal would save approximately $2.9 billion between 2017 and 2023, or approximately $7 billion over 10 years. The CBO estimated in its 2008 report Budget Options, Volume 1: Health Care that imposing a 5 percent excise tax on all Medigap insurers could achieve savings of about $12.1 billion over ten years.23 In general, this approach is designed to discourage the purchase of Medigap policies, but may not have much of an effect on utilization or spending for individuals who choose to purchase a policy with the added fee.

| Table 1. Comparison of Recent Medigap Proposals and Recommendations | ||

| Date Introduced |

Proposal Authors

|

Medigap Provision

|

| April 29, 2013 | Brookings Institution, Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform | Would require Medigap plans to have an actuarially-equivalent co-pay of at least 10 percent. |

| April 18, 2013 | Bipartisan Policy Center | Would require Medigap plans to include a deductible of at least $250, cover no more than 50 percent of beneficiaries’ copayments and coinsurance, and provide an out-of-pocket limit no lower than $2,500, beginning in 2016. |

| April 10, 2013 | President’s FY2014 Budget | Would introduce a surcharge on Part B premiums that would be equivalent to about 15 percent of the average Medigap premium for new beneficiaries that purchase Medigap policies with “particularly low cost-sharing requirements,” beginning in 2017. Current beneficiaries, and individuals who become eligible for Medicare prior to 2017, would not be subject to the premium surcharge. |

| February 26, 2013 | Brookings Institution, The Hamilton Project24 |

Would apply an excise tax of up to 45 percent on Medigap plan premiums. |

| February 19, 2013 | Erskine Bowles and Former Sen. Alan Simpson | Would prohibit Medigap and TRICARE for Life plans from covering the Medicare deductible and no more than 50 percent of the base coinsurance, up to the initial limit; in the interim, would apply a surcharge to the Part B premium of Medigap plans. |

| January 24, 2013 | Sen. Orrin Hatch | Would limit Medigap plans from providing first-dollar coverage for cost-sharing. |

| December 17, 2012 | Joseph Antos | Would change Medigap plans so that policyholders are sensitive to the cost of their medical care. Would modify rules to require insurers to offer Medigap coverage whenever beneficiaries apply for it. |

| December 12, 2012 | Sen. Bob Corker,S. 3673 | Would require the NAIC to review and revise the Medigap benefit packages to allow for revised benefit packages to be implemented by January 1, 2015. Revised plans would be prohibited from covering the unified deductible and more than 50 percent of the cost-sharing after the unified deductible. Medigap policies could not be issued after December 31, 2016 to beneficiaries who previously were not covered by a Medigap policy. |

| November 13, 2012 | Center for American Progress | Would prohibit Medigap plans from covering the first $500 of beneficiaries’ cost-sharing for beneficiaries with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty level, with exemptions for primary care and care for chronic disease. |

| June 2012 | Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) | Recommended applying a surcharge on Medigap plans and other supplemental insurance. |

| March 15, 2012 | Sens. Rand Paul, Lindsey Graham, Mike Lee, and Jim DeMint | Would prohibit all Medigap policies as of January 1, 2014. |

| February 16,2012 | Sens. Richard Burr and Tom Coburn | Would prohibit Medigap plans from covering the first $500 of beneficiaries’ cost-sharing and limit coverage above $500 to 50 percent of the next $5,000 of Medicare cost-sharing. |

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicare and the Federal Budget: Comparison of Medicare Provisions in Recent Federal Debt and Deficit Reduction Proposals,” October 2013. | ||

Almost since the Medicare program’s inception, Medigap policies have been an important source of supplemental insurance for beneficiaries due to Medicare’s relatively high cost-sharing requirements and significant gaps in coverage. Almost one in four (23%) beneficiaries rely on Medigap to supplement their Medicare coverage, half of whom enroll in plans C or F that provide first-dollar coverage. About half of beneficiaries in five states have Medigap as a source of supplemental insurance; in these same five states, one-third of all beneficiaries have elected plans C or F, which provide first-dollar coverage. Medigap policies help to shield beneficiaries from sudden, out-of-pocket costs, allow beneficiaries to more accurately budget their health care expenses, and minimize the paperwork burden for beneficiaries.

Some policymakers have proposed changes to Medigap in the context of broader efforts to reduce federal spending. Some proposals would prohibit Medigap plans from providing first-dollar coverage, while other proposals would apply a premium surcharge on Medigap premiums to discourage the purchase of the policies. Often these proposals are motivated by studies that find most Medicare beneficiaries with Medigap use more Medicare-covered services and incur higher Medicare costs than beneficiaries without supplemental coverage. Exposing Medigap enrollees to higher cost-sharing, by either prohibiting first-dollar coverage or discouraging the purchase of Medigap policies through a surcharge, is projected to reduce total Medicare spending and beneficiary spending, because studies show that individuals use fewer services when confronted with larger cost-sharing requirements. However, for some vulnerable populations, requiring beneficiaries to pay higher cost-sharing could increase spending over the long term, if they forgo necessary services and as a result use more high-cost, acute care services in the future.

Whether a premium surcharge or a prohibition on first-dollar coverage, such policies could have a disproportionate effect on middle-income beneficiaries who are not poor enough for Medicaid, nor have access to employer-sponsored retiree health care. Either policy could also have a disproportionate effect on beneficiaries in Midwest and Plain states with relatively high Medigap enrollment. Striking a balance between the goals of achieving savings, without imposing financial barriers to care, will be challenging as policymakers grapple with the dual issues of rising program costs and the national debt.