Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2020: Findings from a 50-State Survey

As the COVID-19 pandemic expands, needs for health insurance coverage through Medicaid and CHIP will increase for people who get sick and who lose private coverage due to the declining economy. Increasing enrollment for the 6.7 million uninsured individuals who are eligible for Medicaid and facilitating enrollment for the growing numbers of individuals who will become eligible for Medicaid as they lose jobs and incomes decrease will help expand access to care for COVID-19-related needs and health care needs and more broadly. States can adopt a range of options under current rules to increase Medicaid eligibility, facilitate enrollment and continuity of coverage, and eliminate out-of-pocket costs. States can seek additional flexibility through waivers. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act provides states additional options and enhanced federal funding to support state response.

This 18th annual survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) provides data on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2020. The survey findings highlight state variation in policies that affect individuals’ ability to access coverage and care amid the COVID-19 public health crisis. They also provide examples of actions states can take to expand eligibility and simplify enrollment to respond to the COVID-19 epidemic. Further, the survey findings highlight how changes under the ACA to expand Medicaid eligibility and streamline enrollment and renewal processes have better positioned the Medicaid program to respond to a public health crisis such as COVID-19.

Key Findings

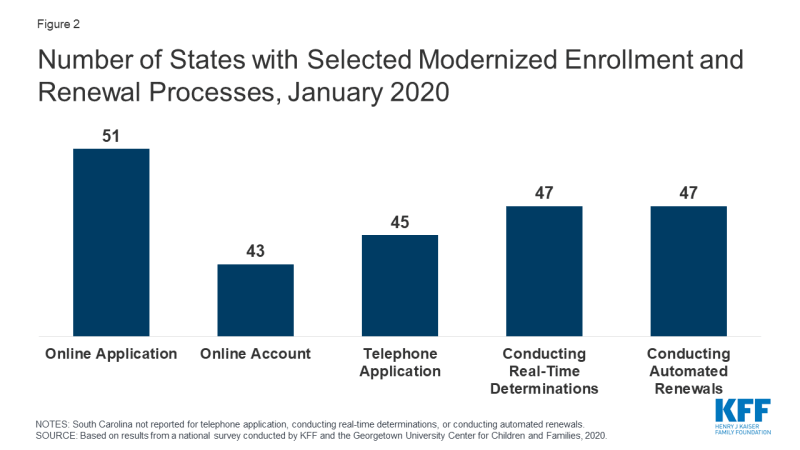

More individuals can access Medicaid coverage in states that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults than states that have not expanded. Across eligibility groups, eligibility levels are higher in expansion states compared to non-expansion states (Figure 1). In 2019, two additional states (Idaho and Utah) implementedhe ACA Medicaid expansion, bringing the total to 36 states that extend eligibility to low-income adults with incomes up to at least 138% federal poverty level (FPL, $29,974 for a family of three) as of January 2020. Eligibility for children and pregnant women held steady in 2019, with median income levels of 255% FPL and 205% FPL across all states, respectively, as of January 2020. Eligibility for parents and other adults remains very limited in the 15 states that have not implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion. In non-expansion states, the median eligibility level for parents is just 41% of the FPL ($8,905 for a family of three), and, with the exception of Wisconsin, other adults are not eligible regardless of their income level.

Figure 1: Median Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits based on Implementation of Medicaid Expansion as of January 2020

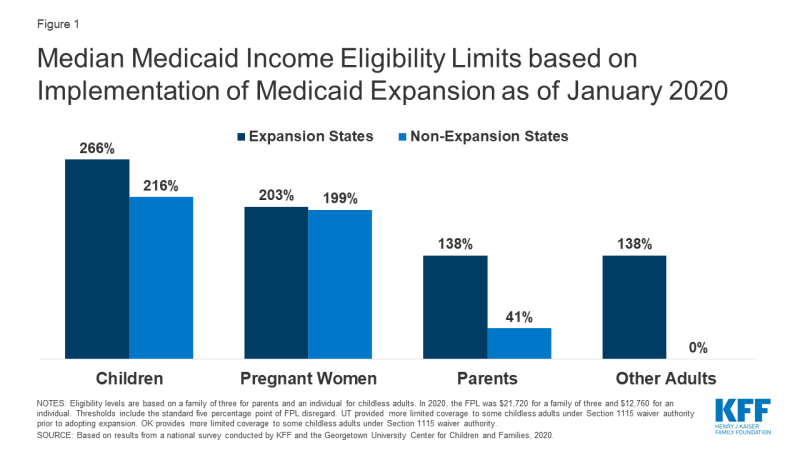

Largely because of the ACA, individuals can apply for Medicaid and CHIP online or via phone, and states can connect individuals to coverage quickly through real-time eligibility determinations and renewals using electronic data matches. In addition to expanding coverage to low-income adults, the ACA established streamlined, electronic data-driven enrollment and renewal processes across states and made enhanced federal funding available to states for system upgrades to implement these processes. As of January 2020, online and phone applications and renewals have become largely standard across states, and most states (43) provide online accounts that enable enrollees to manage their coverage (Figure 2). In contrast, prior to the ACA, individuals could only apply online in two-thirds of states and by phone in one-third of states. Further, as of January 2020, nearly all states are able to make real-time determinations (defined as within 24 hours) and to conduct automated renewals through electronic data matches, with some states achieving high rates of real-time determinations and automated renewals. These advancements mean that individuals may be able to access Medicaid and CHIP coverage more quickly with less administrative burden as coverage needs increase in response to COVID-19.

Eligible individuals may face barriers to maintaining coverage at renewal or when states conduct periodic data matches between renewals. States must renew coverage every 12 months and try to complete renewals using available data before requesting information from an enrollee. When a state requires additional information to complete a renewal, it must provide the enrollee at least 30 days to verify eligibility before terminating coverage. Between annual renewals, enrollees generally must report changes that may affect eligibility, such as fluctuations in income, which are more common among the low-income population. States also may conduct periodic data checks to identify potential changes between renewals, which 30 states reported doing as of January 2020. When states identify a potential change, they must request information to confirm continued eligibility. In contrast to the minimum 30 days provided at renewal, a number of states provide only 10 days from the date of notice for enrollees to respond to information requests for potential changes in circumstances. Eligible individuals may lose coverage at renewal or when these periodic data checks occur if they do not respond to information requests in required timeframes. Enrollees may face a range of challenges to these requests, particularly when given limited time to respond. States can delay or suspend renewals and periodic data checks as one strategy to promote stable coverage as part of COVID-19 response efforts. To access enhanced federal funding under Families First Coronavirus Response Act, states must provide continuous eligibility for enrollees through the end of the month of the emergency period unless an individual asks to be disenrolled or ceases to be a state resident.

Some states have adopted policy options to facilitate enrollment in coverage and promote continuity of coverage. For example, 31 states use presumptive eligibility for one or more groups to expedite enrollment in Medicaid or CHIP coverage by providing temporary coverage to individuals who appear likely eligible while the state processes their full application. In addition, 32 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid or CHIP, enabling them to maintain coverage even if their households have small fluctuations in income. Further, 35 states take into account reasonably predictable changes in income when determining eligibility for Medicaid and 12 states take into account projected annual income for the remainder of the calendar year when determining ongoing eligibility at renewal or when an individual has a potential change in circumstances. Some states also have adopted processes to improve communications with enrollees. For example, 10 states reported taking proactive steps to update enrollee address information, and 24 states report routinely following up on returned mail by calling and/or sending email or text notifications. Additional states could take up these policy and processes as part of COVID-19 response efforts.

Premiums and cost sharing are limited consistent with federal rules that reflect enrollees’ limited ability to pay out-of-pocket health care costs. Under federal rules, states may not charge premiums in Medicaid for enrollees with incomes less than 150% FPL and cost-sharing amounts are limited. Only five states charge premiums or cost sharing for children within Medicaid, while most separate CHIP programs (32 of 35 states) charge premiums, enrollment fees, and/or copayments. Similarly, few states charge premiums, enrollment fees, or other monthly contributions for parents or other adults in Medicaid. However, several states have obtained waivers to impose premiums or other charges in Medicaid for parents or other adults that federal rules do not otherwise allow, and two-thirds of states (35 states) charge copayments for parents and other adults. States can waive or eliminate out-of-pocket costs in response to COVID-19.

Responding to COVID-19

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, the federal government and some states were taking actions to add eligibility requirements and increase eligibility verification for Medicaid coverage. The administration approved waivers in several states to allow work requirements and other eligibility restrictions and released guidance for new “Healthy Adult Opportunity” demonstrations that would allow for such requirements and other changes. Recent court decisions set aside or struck down work requirements and suggested that similar approvals are likely to be successfully challenged in litigation. The administration also indicated plans to increase eligibility verification requirements as part of program integrity efforts. Outside of Medicaid, other policy changes were contributing to downward trends in coverage, including decreased federal funding for outreach and enrollment and shifting immigration policies. However, given increasing health care needs stemming from COVID-19, states and Congress are taking action to expand eligibility, expedite enrollment, promote continuity of coverage, and facilitate access to care.

States can take a range of actions under existing rules to facilitate access to coverage and care in response to COVID-19. They can take some of these actions quickly without federal approval. For example, they can allow self-attestation of eligibility criteria other than citizenship and immigration status and verify income post enrollment. They can also provide greater flexibility to enroll individuals who have small differences between self-reported income and income available through data matches. Further, they can suspend or delay renewals and periodic data checks between renewals. States can take other actions allowed under existing rules by submitting a state plan amendment (SPA, which is retroactive to the first day of the quarter submitted). Changes states can implement through a SPA include expanding eligibility, adopting presumptive eligibility, providing 12-month continuous eligibility for children, and modifying benefit and cost sharing requirements, among others. Beyond these options, states can seek additional flexibility through Section 1135 and Section 1115 waivers.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act provides additional options for states and increases federal funding for Medicaid, subject to states meeting certain eligibility and enrollment requirements. Specifically, it provides coverage for COVID-19 testing with no cost sharing under Medicaid and CHIP (as well as other insurers) and provides 100% federal funding through Medicaid for testing provided to uninsured individuals for the duration of the emergency period associated with COVID-19. The law also provides states and territories a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate for Medicaid for the emergency period. To receive this increase, states must meet certain requirements including: not implementing more restrictive eligibility standards or higher premiums than those in place as of January 1, 2020; providing continuous eligibility for enrollees through the end of the month of the emergency period unless an individual asks to be disenrolled or ceases to be a state resident; and not charging any cost sharing for any testing services or treatments for COVID-19, including vaccines, specialized equipment or therapies.