Women and HIV in the United States

Key Facts

- Women have been affected by HIV since the beginning of the epidemic and face unique challenges in accessing optimal prevention, care and treatment resources.1,2 In 2018, women accounted for about 1 in 5 (19%) new HIV diagnoses in the U.S.3

- Women of color, particularly Black women, have been especially hard hit and represent the majority of women living with HIV as well as the majority of new infections among women.4,5

- However, there has been some significant progress with new HIV diagnoses declining 24% among women since 2010.6

- Despite this progress, HIV prevention opportunities may not be reaching women effectively. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a highly effective medication, prevents acquisition of HIV but uptake has been slow among women in the U.S.7

- While there are promising new signs, with data indicating that HIV infections are now falling among women, including among Black women, addressing the epidemic’s impact on women in the U.S., particularly women of color, remains critical to ensuring that these trends continue.8,9

Overview

- Today, of the more than 1.1 million people living with HIV in the U.S., 258,000, or 23%, are women.10

- Women with and at risk for HIV face several challenges to getting the services and information they need, including socio-economic and structural barriers such as poverty, cultural inequities, and intimate partner violence (IPV). In addition, women may place the needs of their families above their own.11,12,13,14,15

- Women accounted for 19% (7,139) of new HIV diagnoses in 2018, a 24% decrease since 2010.16

- In 2018, there were 4,106 new AIDS diagnoses (AIDS being the most advanced form of HIV disease) among women, representing 24% of all AIDS diagnoses in that year. An AIDS diagnosis suggests someone who was living with HIV for a long time before being diagnosed or suboptimal engagement in care. Like new HIV infections, new AIDS diagnoses among women are on the decline, likely linked to fewer new infections, better engagement in care, and earlier diagnoses.17

Age

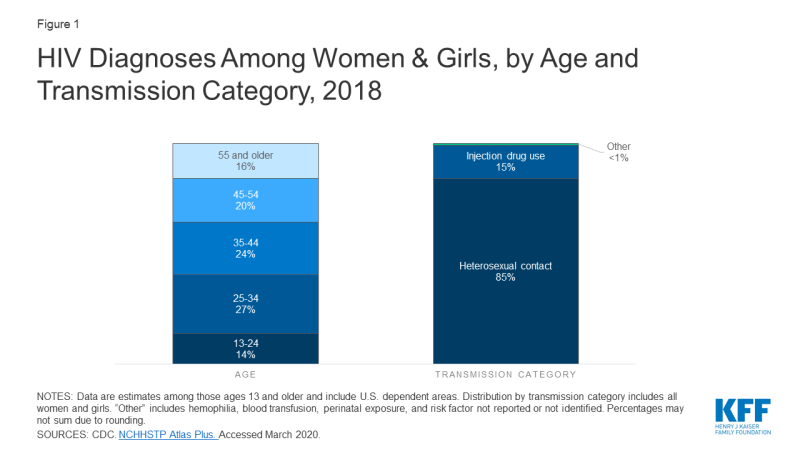

- Women ages 25-34 accounted for the largest share (27%) of HIV diagnoses among women in 2018, followed by those ages 35-44 (24%). Most women (85%) who were diagnosed in 2018 acquired HIV through heterosexual sex (Figure 1).18

- Women are diagnosed with HIV at slightly older ages than men are. Men ages 13-34 accounted for 60% of HIV diagnoses among men in 2018, while women in the same age group accounted for 40% of HIV diagnoses among women in 2018.19

Race/Ethnicity

- Women of color, particularly Black women, are disproportionately affected by HIV, accounting for the majority of new HIV infections, the greatest prevalence, and highest rates of HIV-related deaths among women living with HIV in the U.S.20

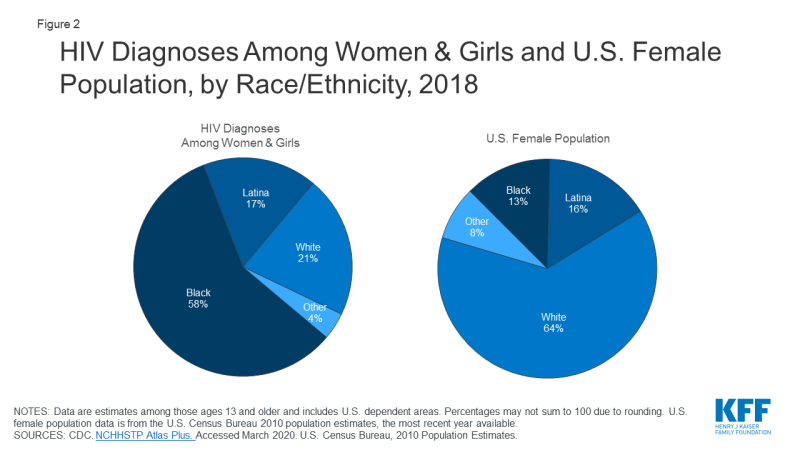

- In 2018, Black women accounted for over half (58%) of HIV diagnoses among women, while only accounting for 13% of the female population; white women accounted for 21% and Latinas 17% of HIV diagnoses among women (Figure 2).21,22,23 Recent data indicate that, as with women overall, HIV diagnoses among Black women are also on the decline, decreasing by31% between 2010 and 2018.24

- HIV incidence rates are much higher for Black women and Latinas than for white women. In 2016, the rate of new HIV infections for Black women was 15 times higher than the rate for white women (24.2 per 100,000 compared to 1.6); the rate for Latinas (4.9) was 3 times higher.25 Rates of women living with an HIV diagnosis follow a similar pattern. 26

- The likelihood of a woman being diagnosed with HIV in her lifetime is significantly higher for black women (1 in 54) and Latinas (1 in 256) than for white women (1 in 941).27

- In 2017, HIV was the 7th leading cause of death for Black women ages 25-44 and was the 18th leading cause of death among white women in this age group.28 Black women accounted for the greatest share of deaths among women with a diagnosed HIV infection in 2017 (58%), followed by white women (21%) and Latinas (15%).29

- When asked how concerned they were personally about becoming infected with HIV, a survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS found that 21% of women in the U.S. say they are “very” or “somewhat” concerned.30 An earlier survey found that Black women are much more likely to say they are concerned than white women and that Black women are also more likely to express concern about an immediate family member acquiring HIV.31

Transmission

- As seen in Figure 1, women are most likely to contract HIV through heterosexual sex (85% in 2018), followed by injection drug use (15%).32 Heterosexual transmission accounts for a greater share of HIV diagnoses among Black women and Latinas (92% and 87%, respectively) compared to white women (65%); injection drug use accounts for a greater share of diagnoses among white women (34%).33

- Mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the U.S. has decreased dramatically since its peak in 1991 due to the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), which significantly reduces the risk of transmission from a woman to her baby (to 1% or less).34,35 Still, some perinatal infections occur each year, the majority of which are among Black women, and there continues to be missed opportunities for preventing mother-to-child transmissions, such as testing late in pregnancy.36,37

Reproductive Health

- HIV interacts with women’s reproductive health on many levels.

- Studies have shown that HIV is transmitted more efficiently from men to women during heterosexual sexual intercourse. In addition, women with other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are at increased risk for contracting HIV. 38,39

- Women with HIV are at increased risk for developing or contracting a range of conditions, including human papillomavirus (HPV), which can lead to cervical cancer, and severe pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).40

- Research efforts are exploring a number of new HIV prevention technologies which could be particularly beneficial for women, such as cervical barriers and microbicides.41

- In addition, family planning sites provide an important entry point for reaching women at risk for and living with HIV. A majority of women of reproductive age (59%) report that a family planning as a site of reproductive care services; 41% say it is their only source of care.42

Geography

- HIV’s impact varies across the country and, in some states, the epidemic is more likely to affect women than in others.

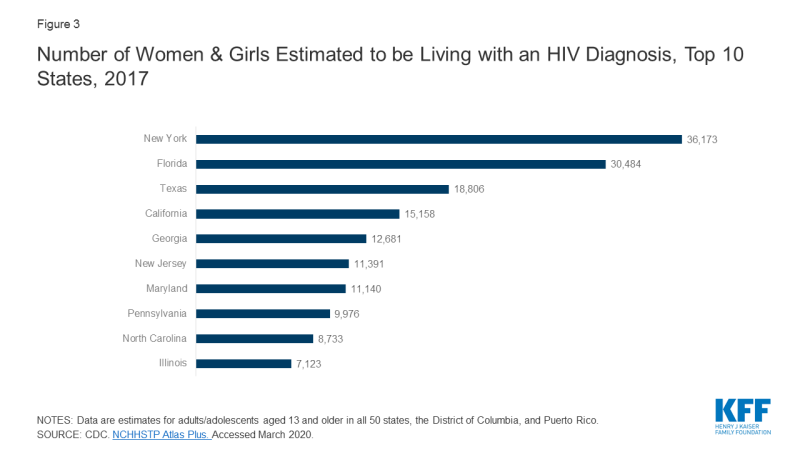

- Ten states account for the majority of women living with an HIV diagnosis (67% in 2017); with 5 states accounting for nearly half (47%) (Figure 3). While the District of Columbia has far fewer women living with an HIV diagnosis (3,848 in 2017), the rate per 100,000 women living with an HIV diagnosis is nearly 7 times the national rate for women (1,214.8 per 100,000 compared to 169.9 per 100,000 nationally).

- Twenty-five (25) counties account for almost half (44%) of all women living with an HIV diagnosis in the U.S. Bronx County, New York had the greatest number (9,960) and highest rate (1,576.5 per 100,000) of women living with an HIV diagnosis. 43

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and HIV

- Women living with HIV are disproportionately affected by intimate partner violence (IPV), including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse compared to the general population. 44,45 Intimate partner violence (IPV), sometimes referred to as domestic violence, has been shown to be associated with increased risk for HIV among women, as well as poorer treatment outcomes for those who are already infected.46,47

- Among all U.S. women, 36% report having experienced IPV, including rape, physical violence, and/or stalking in their lifetime; among HIV positive women in the U.S., IPV is even more prevalent, with 55% reporting having experienced IPV.48,49,50

- In many cases, the factors that put women at risk for contracting HIV are similar to those that make them vulnerable to experiencing trauma or IPV; women in violent relationships are at a 4 times greater risk for contracting STIs, including HIV, than women in non-violent relationships, and women who experience IPV are more likely to report risk factors for HIV.51 These experiences are interrelated and can become a cycle of violence, HIV risk, and HIV infection.

- It has also been suggested that women are at risk of experiencing violence upon disclosure of their HIV status to partners.52

HIV Prevention

- The CDC recommends routine HIV screening for all adults, including women, ages 13-64, in health care settings, as well as repeat screening at least annually for those at high risk. The CDC also separately recommends all pregnant women be screened for HIV, and that those at high-risk for HIV have repeat HIV screening in their third trimester. Testing of newborns is also recommended if the mother’s HIV status is unknown.53

- While nearly half (49%) of women in the U.S. ages 18-64 report having been tested for HIV at some point, just 1 in 6 (18%) report that they were tested in the past year. Black women are much more likely to report having been tested in the past year compared to white women (21% compared to 6%).54

- The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends HIV testing (including specifically for pregnant women), IPV screening, many STI screenings, and PrEP which means that most insurers are required to cover these services without cost-sharing.55,56

Access to Care & Treatment

- There are a number of sources of care and treatment for women with and at risk for HIV in the U.S., including government programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, and the Ryan White Program for those who are eligible.

- Looking across the spectrum of access to care, from HIV diagnosis to viral suppression, reveals missed opportunities for reaching women. Among women living with HIV in the U.S., 9 in 10 (89%) were aware of their HIV status; however, many were tested late, many years after acquiring HIV, suggesting missed prevention opportunities. Moreover, only 65% have been linked to care and just 51% are retained in regular care and are virally suppressed.57

- In 2017, among women who are HIV positive, 22% were tested for HIV late in their illness – that is, simultaneously diagnosed with HIV and AIDS – a similar share as men (21%).58

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a highly effective medication, prevents acquisition of HIV, but uptake has been slow among women in the U.S., suggesting potential barriers to the provision of PrEP for women. In 2016, women accounted for only 4.7% of PrEP users in the U.S.59

Future Outlook

While data indicate that HIV incidence among women in the U.S. is falling, addressing the epidemic’s impact on women remains of critical importance in ensuring these encouraging trends continue. While there are a number of sources of care and treatment for women with HIV, including new coverage opportunities under the Affordable Care Act, half of women are not engaged in care and treatment and challenges remain. Looking forward, it will be important to continue to assess an evolving, epidemiological, scientific, and policy landscape. Of particular note, whether the White House initiative to “End the HIV Epidemic” in the U.S., impacts coverage and access to prevention, care, and treatment for women with and at risk for HIV will be critical to monitor.

Endnotes

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2018, Vol. 30; November 2019.

CDC. Kaiser Family Foundation Special Data Request.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed February 2020.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2018, Vol. 30; November 2019.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States 2010-2016, Vol. 24, No 1; February 2019.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. MMWR, HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis, by Race and Ethnicity – United States, 2014-2016; October 2018.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2018, Vol. 30; November 2019.

CDC. Fact Sheet: HIV Among Women; January 2020.

CDC. Supplemental Surveillance Report. Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States 2010–2016 Vol 24. No. 1. February 2019.

CDC. Fact Sheet: HIV Among Women; January 2019.

White House. Presidential Memorandum Establishing a Working Group on the Intersection of HIV/AIDS, Violence Against Women and Girls, and Gender-related Health Disparities; March 2012.

Denning P and DiNenno E. “Communities in Crisis: Is There a Generalized HIV Epidemic in Impoverished Urban Areas of the United States?” August 2010.

HRSA. CAREAction Newsletter: Ryan White Providers Address HIV/AIDS Among African American Women; September 2012.

Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), and Women: An Emerging Policy Landscape, 2019.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

Among those ages 13 and older.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Population Estimates.

CDC. Fact Sheet: HIV Among Women; January 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

Hess KL et al. “Lifetime Risk of a Diagnosis of HIV Infection in the United State.” Annals of epidemiology, Vol. 27, No. 4; April 2017.

CDC. Slide Set: HIV Mortality, 2017.

CDC. Slide Set: HIV Surveillance in Women, 2018 Preliminary.

Analysis from additional data. KFF. Health Tracking Poll – March 2019: Public Opinion on the Domestic HIV Epidemic, Affordable Care Act, and Medicare-for-all; March 2019.

The Washington Post/KFF. 2012 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS; July 2012.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

Nesheim S et al. “A Framework for Elimination of Perinatal Transmission of HIV in the United States.” Pediatrics, Vol. 130, No. 4; September 2012.

CDC. HIV Among Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children, March 2019.

Whitmore SK et al. “Correlates of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in the United States and Puerto Rico.” Pediatrics, Vol. 129, No. 1; January 2012.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data, Vol. 24, No. 3; June 2019.

CDC. Fact Sheet: HIV Among Women; March 2019.

See: https://www.womenshealth.gov/hiv-and-aids/living-hiv/hiv-and-womens-health; last updated January 2019.

See: https://www.womenshealth.gov/hiv-and-aids/living-hiv/hiv-and-womens-health; last updated January 2019.

HIV.gov. Microbicides webpage: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/hiv-prevention/potential-future-options/microbicides; updated May 2017.

Frost JJ et al. “Specialized Family Planning Clinics in the United States: Why Women Choose Them and Their Role in Meeting Women’s Health Care Needs.” Women’s Health Issues, Vol. 22, No. 6; November 2012.

CDC. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. Accessed March 2020.

CDC. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief, November 2018.

CDC. Intersection of Intimate Partner Violence and HIV in Women, February 2014.

CDC. Intersection of Intimate Partner Violence and HIV in Women, February 2014.

E. L. Machtinger, J. E. Haberer, T. C. Wilson, and D. S. Weiss. “Recent Trauma is Associated with Antiretroviral Failure and HIV Transmission Risk Behavior Among HIV-Positive Women and Female-Identified Transgenders.” AIDS and Behavior. 16:8(2012): 2160–2170.

Matthew J. Breiding, Jieru Chen, and Michele C. Black. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: Intimate Partner Violence in the United States – 2010. Atlanta, GA, 2014.

Machtinger, E.L., et al. (2012) Psychological Trauma and PTSD in HIV-Positive Women: A Meta-Analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 16(8): 2091-2100.

CDC. Intersection of Intimate Partner Violence and HIV in Women, February 2014.

CDC. Intersection of Intimate Partner Violence and HIV in Women, February 2014.

Andrea Carlson Gielen, Karen A. McDonnell, Jessica G. Burke, and Patricia O’Campo. “Women’s Lives After an HIV-Positive Diagnosis: Disclosure and Violence.” Maternal and Child Health Journal. 4:2(2000):111-119.

CDC. MMWR, Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings, September 2006.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of CDC’s National Health Interview Survey data, 2017.

PrEP coverage without cost-sharing may not begin until 2021.

For more detail on the role of the USPSTF and coverage of these services see the following factsheet on HIV testing for an example: Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV Testing in the United States. June 2019. https://www.kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/hiv-testing-in-the-united-states/

CDC. Fact Sheet: HIV Among Women; January 2020.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data, Vol. 24, No. 3; June 2019. HIV diagnosis data are estimates from 41 states and the District of Columbia.

CDC. MMWR, HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis, by Race and Ethnicity – United States, 2014-2016; October 2018.