How Many Employers Could be Affected by the Cadillac Plan Tax?

As fall approaches, we can expect to hear more about how employers are adapting their health plans for 2016 open enrollments. One topic likely to garner a good deal of attention is how the Affordable Care Act’s high-cost plan tax (HCPT), sometimes called the “Cadillac plan” tax, is affecting employer decisions about their health benefits. The tax takes effect in 2018.

The potential of facing an HCPT assessment as soon as 2018 is encouraging employers to assess their current health benefits and consider cost reductions to avoid triggering the tax. Some employers announced that they made changes in 2014 in anticipation of the HCPT, and more are likely to do so as the implementation date gets closer. By making modifications now, employers can phase-in changes to avoid a bigger disruption later on. Some of the things that employers can do to reduce costs under the tax include:

- Increasing deductibles and other cost sharing;

- Eliminating covered services;

- Capping or eliminating tax-preferred savings accounts like Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), or Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs);

- Eliminating higher-cost health insurance options;

- Using less expensive (often narrower) provider networks; or

- Offering benefits through a private exchange (which can use all of these tools to cap the value of plan choices to stay under the thresholds).

For the most part these changes will result in employees paying for a greater share of their health care out-of-pocket.

In addition to raising revenue to fund the cost of coverage expansion under the ACA, the HCPT was intended to discourage employers from offering overly-generous benefit plans and help to contain health care spending. Health benefits offered through work are not taxed like other compensation, with the result that employees may receive tax benefits worth thousands of dollars if they get their health insurance at work. Economists have long argued that providing such tax benefits without a limit encourages employers to offer more generous benefit plans than they otherwise would because employees prefer to receive additional benefits (which are not taxed) in lieu of wages (which are). Employees with generous plans use more health care because they face fewer out-of-pocket costs, and that contributes to the growth in health care costs.

The HCPT taxes plans that exceed certain cost thresholds beginning in 2018. The 2018 thresholds are $10,200 for self-only (single) coverage and $27,500 for other than self-only coverage, and after that they generally increase annually with inflation. The amount of the tax is 40 percent of the difference between the total cost of health benefits for an employee in a year and the threshold amount for that year.

While the HCPT is often described as a tax on generous health insurance plans, it actually is calculated with respect to each employee based on the combination of health benefits received by that employee, and can be different for different employees at the same employer and even for different employees enrolled in the same health insurance plan. While final regulations have not yet been issued, the cost for each employee generally will include:

- The average cost for the health insurance plan (whether insured or self-funded);

- Employer contributions to an (HSA), Archer medical spending account or HRA;

- Contributions (including employee-elected payroll deductions and non-elective employer contributions) to an FSA;

- The value of coverage in certain on-site medical clinics; and

- The cost for certain limited-benefit plans if they are provided on a tax-preferred basis.

The inclusion of FSAs here is important. FSAs generally are structured to allow employees the opportunity to divert some of their pay to pretax health benefits, which means that they can avoid payroll and income taxes on money they expect to use for health care. Employees often are permitted to elect any amount of contribution up to a cap (which is $2,550 in 2015), which means that the amount of benefits for an employee subject to the HCPT in a year could vary depending on their FSA election.

The amount and structure of the HCPT provide a strong incentive for employers to avoid hitting the thresholds. The tax rate of 40 percent is high relative to the tax that many employees would pay if the benefits were merely taxed like other compensation, and the ACA does not allow the taxpayers (e.g., the employer) to deduct the tax as a cost of doing business, which can significantly increase the tax incidence for for-profit companies. Further, to avoid the perception that this was a new tax on employees, the HCPT was structured as a tax on the service providers of the health benefit plans providing benefits an employee: insurers in the case of insured health benefit plans; employers in the case of HSAs and Archer MSAs; and the person that administers the benefits, such as third party administrators, in the case of other health benefits. While it is generally expected that insurers and service providers will pass the cost of the tax back to the employer, doing so may not always be straightforward. Because there can be numerous service providers with respect to an employee, the excess amount must be allocated across providers. In some cases, it may not be possible to know whether or not the benefits provided to an employee will exceed the threshold amount until after the end of a year (for example, in the case of an experience-rated health insurance plan), which means that service providers may need to bill the employer retroactively for the cost of the tax they must pay. Amounts that employers provide to reimburse service providers for the HCPT create taxable income for the service provider, which the parties will want to account for in the transaction. The IRS has requested comments on potential methods for determining tax liability among benefit administrators, including a way that could assign the responsibility to the employer in cases other that insured benefit plans. The proposed approach could simplify administration of the tax.

How the High-Cost Plan Tax Works

Let’s take an employer that, in 2018, offers employees an HSA-qualified health plan with a total annual premium of $7,800 ($650 monthly) for single coverage. The employer makes an annual contribution of $780 to HSAs established by its employees, and offers a FSA plan where employees can elect to contribute up to $2,700 (the estimated legal maximum) for the year through payroll deduction. Employee A enrolls in single coverage under the plan for all 12 months but does not elect to contribute to an FSA while employee B enrolls in single coverage under the plan for all 12 months and elects to make the maximum FSA contribution. For employee A, the monthly health benefit cost would be the sum of $650 for the health plan premium and $65 (one-twelfth of the annual HSA contribution by the employer), or $715. Because this is less than the monthly threshold amount for single coverage of $850 (one-twelfth of $10,200), no HCPT would be owed for employee A. For employee B, the monthly health benefit cost would be the sum of $650 for the health plan premium, $65 (one-twelfth of the annual HSA contribution by the employer) and $225 (one-twelfth of the annual FSA contribution), or $940. Because this is more than the monthly threshold amount for single coverage of $850, there would be a HCPT for employee B for the month equal to 40 percent of the health benefit cost in excess of the threshold. The excess amount in this case is $90 ($940 – $850), and 40 percent of the excess is $36. The annual HCPT owed for employee B would be $432.

To illustrate the impact of the HCPT, we created a simple model of future plan costs, based on the distribution of employer-sponsored plans from the 2015 Kaiser/HRET Employer Health Benefits Survey (EHBS), and estimated the share of employers with plans that could be expected to hit the HCPT threshold in 2018, 2023 and 2028 if plan premiums grew at a range of reasonable rates. The EHBS has information about plan premiums, and employer contributions to HSAs and HRAs, but generally does not ask about the details of other health benefits offered to employees. While we can identify which employers make an FSA option available to employees, we do not have information about permitted or actual contribution levels.

Our estimates focus on the self-only plan threshold because the EHBS asks about premiums for a family of four while the HCPT threshold for family coverage applies to any family enrollment (such as couple or single plus one) other than self-only. We assume that premiums and employer contributions to HSAs and HRAs would rise five percent annually, which is consistent with estimates of future health care cost increases. We also present tables showing how the results would change if premiums, HSA and HRA contributions were to grow annually at four and six percent. Employers in the EHBS provide information about their largest plan for up to four plan types (health maintenance organization, preferred provider organization, point of service plan, high deductible health plan combined with a savings option) and we assess the cost each plan option separately to determine if the cost would exceed the HCPT threshold. We do not have information that would allow us to make adjustments permitted by the ACA for plans with older workers, plans in certain industries, or multiemployer plans, which means we may be somewhat over-counting the percent of these firms reaching the threshold. Other limitations are discussed in the methods (see below).

Two sets of estimates are presented. The first is based on the premiums for health coverage plus employer contributions for HSAs and HRAs, while the second includes the effects of FSA plans as well to illustrate how FSA elections impact the number of plans affected. We assume that employees offered an FSA option are permitted to elect contributions up to the maximum allowed by law, and that some employees do so.

The purpose here is to look at the share of current plans that might meet the definition of “high cost” over time, assuming modest premium growth and no changes to the plan. We do not attempt to estimate the share of employer plans that will actually be assessed under the HCPT, as we believe its high tax rate and potentially complicated structure will encourage most employers to make plan adjustments to avoid the tax for as long as they can. These estimates can be understood as the share of employers who have plans where the cost for some employees will exceed the thresholds for the HCPT, presenting employers with a choice of whether to pay the tax or (more likely) restructure their benefits to avoid it.

Estimates

Looking first at the expected costs for just plan premiums plus employer contribution to HSAs and HRAs, we estimate that about 16 percent of employers offering health benefits would have at least one health plan that would exceed the $10,200 HCPT self-only threshold in 2018, the first year that plans are subject to the tax (Table 1). The percentage would increase to 22 percent in 2023 and to 36 percent in 2028.

| Table 1: Share of Employers with At Least One Plan Hitting Threshold | |||

| Year | HCPT Self-Only Threshold | Premium, HSA, HRA | Premium, HSA, HRA & FSA |

| 2018 | $10,200 | 16% | 26% |

| 2023 | $11,800 | 22% | 30% |

| 2028 | $13,500 | 36% | 42% |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis | |||

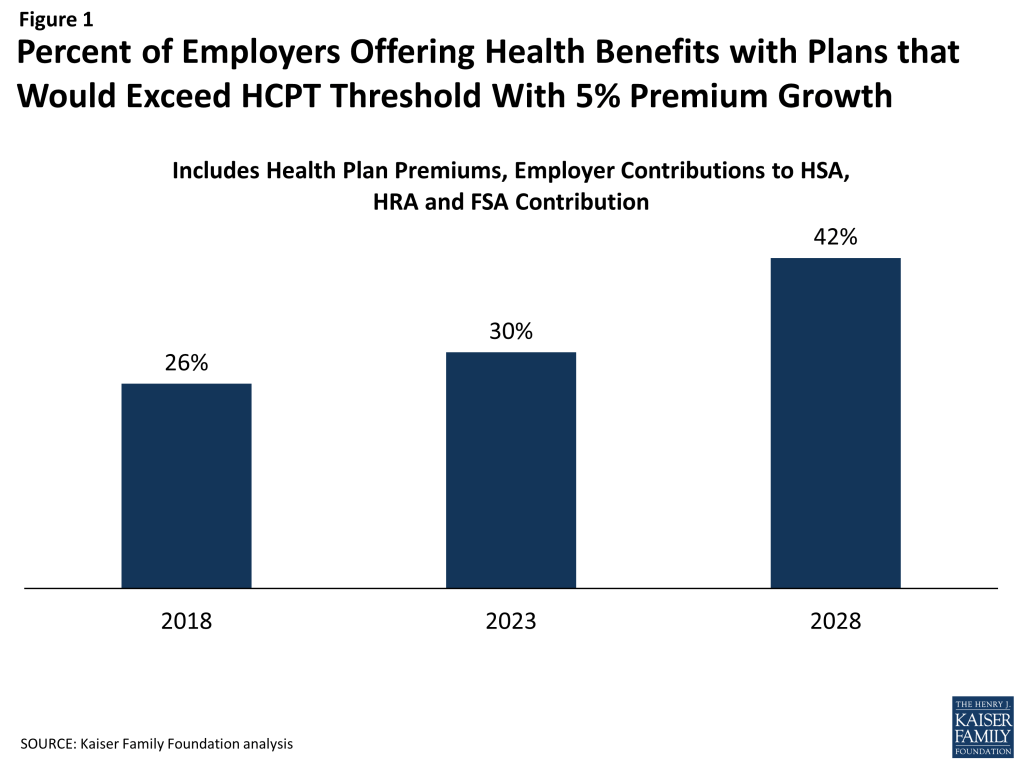

These percentages rise significantly when we consider the impact that FSA options can have: up to 26 percent in 2018, 30 percent in 2023 and 42 percent in 2028 (Figure 1).

This should not be surprising since the maximum FSA contribution levels (estimated to be $2,700 in 2018, $3,100 in 2023 and $3,600 in 2028) are quite large and generally are additive to other benefit costs for employees that elect to contributions. As we noted above, not all employees offered an FSA option will make the maximum contribution, and some will make no contribution, which means that the threshold will be reached for some employees and not for others with the same plan choices. For example, consider two employees offered a PPO with a premium of $9,000 in 2018 and an FSA option that permits a payroll deduction of up to $2,700. If one employee elects not to contribute to the FSA, the threshold is not met for that employee and no tax is owed. If the other employee contributes the full amount, the threshold is hit and a 40 percent tax is assessed on the excess ($1,500) allocated between the administrators or the PPO and the FSA (if they are different). For the percentages above, we count a plan as exceeding the threshold if an employee who elected the maximum FSA contribution would cause the plan to exceed the threshold for that employee. Because large firms (200 or more workers) are much more likely than smaller firms to offer an FSA, large firms are much more likely to have a plan that exceeds the HCPT threshold when FSA contributions are considered (Table 2).

| Table 2: Share of Employers with At Least One Plan Hitting Threshold By Firm Size | |||

| Year | HCPT Self-Only Threshold | Premium, HSA, HRA & FSA | |

Small Firms (3-199 workers) | Large Firms (200 or more workers) | ||

| 2018 | $10,200 | 25% | 46% |

| 2023 | $11,800 | 29% | 56% |

| 2028 | $13,500 | 41% | 68% |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis | |||

The assumed rate of premium growth also has a large impact on these estimates, particularly in the later years (Table 3). The HCPT thresholds increase with inflation, so what matters over the longer run is the difference between the growth in benefit costs and inflation. With our inflation assumption of 2.7 percent annually between 2018 and 2028, a four percent annual growth in health plan costs would reduce the 2028 percentage to 29 percent when FSA offers are considered, while a six percent annual growth in premiums would increase the percentage to 54 percent. This wide range shows how sensitive the effects of the tax are to premium growth in excess of inflation, and how those effects compound over time.

| Table 3: Share of Employers with At Least One Plan Hitting Threshold, Different Premium Growth Assumption | ||||

| Year | HCPT Self-Only Threshold | Premium, HSA, HRA & FSA | ||

4% Premium Growth | 5% Premium Growth | 6% Premium Growth | ||

| 2018 | $10,200 | 24% | 26% | 27% |

| 2023 | $11,800 | 26% | 30% | 38% |

| 2028 | $13,500 | 29% | 42% | 54% |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis | ||||

Discussion

Our estimates suggest that a meaningful percentage of employers would need to make changes in their health benefits to avoid the HCPT in 2018, and that this percentage grows significantly over time unless employers are able to keep heath plan cost increases at low levels. In fact, 19 percent of employers already in 2015 have a plan that would exceed the HCPT threshold when FSA offers are considered; these firms would need to reduce their current plan costs over the next several years to avoid the tax. We estimate that by 2028, 42% of employers would have plans where costs would exceed the threshold for some or all employees. To the extent that health plan premiums continue to grow faster than inflation – a likely scenario – the share of employers affected by the HCPT will grow and eventually reach 100 percent. To avoid the tax, an employer would have to keep plan costs below the threshold and contain growth in costs over time to no more than inflation.

In addition to raising revenue to fund the expansion of coverage under the ACA, the HCPT provides powerful incentives to control health plans costs over time, whether through efficiency gains or shifts in costs to workers in the form of higher deductibles and other patient cost-sharing.

The design of the HCPT also has several implications for how employers structure and administer their health benefits, including:

The potential complexity of the tax may cause employers to simplify their health benefit offerings. The tax is calculated on total costs for an employee across health benefit programs but assessed separately against coverage providers. For employers that use multiple providers for health benefits, the employer and service providers may not know until the end of the year whether or not they owe a tax or how much it may be. The potential complications associated with allocating the tax burden and managing reimbursements to insurers (and potentially other services providers) may encourage employers to simplify their benefit arrangements and reduce the number of options that employees have and the number of coverage providers involved. The IRS is considering an option where the employer could be considered the benefit provider (and therefore the party that owes the tax) for most benefit arrangements, including self-funded health plans, although this would not be possible where there is an insured health plan (where the tax is assessed against the health insurer).

The HCPT threshold may be passed for some employees of an employer but not for others if employees are able to choose different amounts of benefits. This may make employers reluctant to give employees the ability to select benefit options that have the potential to trigger the tax. One current benefit that may be at particular risk is the option to contribute to an FSA because, as currently structured, it allows employees to add up to several thousand dollars to their benefit costs. These plans are separate from the core health insurance options provided by employers, so limiting or eliminating them provides a way for employers to lower costs without affecting the plans that most employees rely upon and value the most. Employers also may consider reducing other ancillary health benefit options (e.g., critical disease or hospital indemnity plans) offered on a pre-tax basis if the cost of the core health insurance plans approach the HCPT thresholds.

The significant tax rate, which would likely be borne by the employer (either directly or through reimbursing tax paid by coverage providers), may cause employers to limit employee choice generally and even among core health insurance offerings. Discussions about employee health benefits often focus on giving employees choices and sometimes focus on making employees aware of costs by having them pay all of the additional costs if they select more expensive plans. Under the HCPT, a significant additional cost for plans that exceed the threshold is borne in the first instance by the employer, who may be reluctant to permit employees to elect these plans if it can be avoided. Employers could structure the employee contributions for plans above the threshold so that they include a surcharge, which would pass the tax incidence on to the employees who selected the plans. Doing so would require knowing before the beginning of the year if, and (perhaps roughly) by how much, the options selected by an employee would exceed the threshold. This approach would be possible for an employer sponsoring multiple plan options on its own or offering insured health benefits through a private exchange (where the insurers could collect the additional contribution).

Employers considering this design would need to assess whether, and which, employees would be willing to pay a high surcharge to elect these more expensive benefit options. Plan choice generally results in employees that are less healthy selecting more comprehensive benefit options, and putting a surcharge on these options would increase the adverse selection against these plans, increasing their costs. If the additional contribution for an employee was small (for instance, the excess cost above the threshold is modest), enrollment may not fall too much, but if the additional contribution was large, or grew larger over time, enrollment in the more expensive options would likely shrink and skew less and less healthy. This could affect the viability of these plan options.

We expect employers to make modifications to their health benefit plans over the next several years to avoid or delay hitting the threshold for the HCPT. While some will need to move more quickly than others, the tax will be an important contrast for a large share of employers within the next decade.

Methods

We used information about the premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance from the 2015 Kaiser/HRET Employer Health Benefits Survey (EHBS) to estimate the percentage of employers that would have at least one health plan that would be subject to the High Cost Plan Tax (HCPT) assuming certain future rates of premium growth. The EHBS is an annual survey that collects information about health benefits offered by about 2,000 employers with three or more employees.

The EHBS collects information from responding employers about their largest plan for up to four plan types — health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), point of service plan (POS), and high deductible health plan offered with a savings account (HDHP/SO). An HDHP/SO is a plan with a single deductible of $1,000 or more offered with a health reimbursement arrangement (HRA), or a health plan that qualifies the employee to make contributions to a Health Saving Account (HSA). The EHBS asks respondents for the premium for single coverage and for a family of four for their largest plan in each plan type. For HDHP/SOs, the amounts that employers contribute to employees’ HSAs or make available to employees through HRAs are also collected. Periodically, including in 2015, the EHBS asks about whether or not the employer sponsors a flexible spending account (FSA) but does not obtain information about participation or the amounts contributed.

For the estimates, we took the single premium for each health plan offered by responding employers and increased them by five percent annually. We also looked at alternate scenarios with a four percent and a six percent increase. For HSA qualified plans we added the amount that employers contribute to employees’ HSAs to the premium. For high deductible health plans offer with an HRA, the survey collects information about the amounts employers make available to employees but not the amounts that are actually contributed. To be conservative, we added one-half of the amount that employers make available through the HRA to the plan premium. The HSA and HRA amounts were also increased by the percentages above. A five percent annual growth rate is roughly consistent with the historic trend for these contributions. For employers that reported offering an FSA, we added the maximum contribution amount permitted for an FSA to the estimated premium for each plan type except HSA qualified plans for each of the three years. We did not add the FSA amount to the premium for HSA qualified plans because generally a person cannot establish an HSA if they have an FSA that could reimburse expenses before the plan deductible is met. We used the maximum contribution amount because we were looking to see if the cost for the plan could exceed the threshold for an employee. The total costs for each plan for 2018, 2023 and 2028 were compared to the estimated HCPT thresholds to determine if any plan offered by an employer would hit the threshold.

To calculate the HCPT thresholds, we assumed that inflation increase annually by 2.7 percent between 2018 and 2028. This is consistent with the assumptions used in the 2015 Medicare Trustees Report. We also used the Trustee’s assumed annual inflation from 2015 to 2028 to calculate the maximum FSA contribution amounts.