How Much Is Enough? Out-of-Pocket Spending Among Medicare Beneficiaries: A Chartbook

As part of efforts to rein in the federal budget and constrain the growth in Medicare spending, some policy leaders and experts have proposed to increase Medicare premiums and cost-sharing obligations. Today, 54 million people ages 65 and over and younger adults with permanent disabilities rely on Medicare to help cover their health care costs. With half of all people on Medicare having incomes of less than $23,500 in 2013, and because the need for health care increases with age, the cost of health care for the Medicare population is an important issue.1

Although Medicare helps to pay for many important health care services, including hospitalizations, physician services, and prescription drugs, people on Medicare generally pay monthly premiums for physician services (Part B) and prescription drug coverage (Part D). Medicare has relatively high cost-sharing requirements for covered benefits and, unlike typical large employer plans, traditional Medicare does not limit beneficiaries’ annual out-of-pocket spending. Moreover, Medicare does not cover some services and supplies that are often needed by the elderly and younger beneficiaries with disabilities—most notably, custodial long-term care services and supports, either at home or in an institution; routine dental care and dentures; routine vision care or eyeglasses; or hearing exams and hearing aids.

Many people who are covered under traditional Medicare obtain some type of private supplemental insurance (such as Medigap or employer-sponsored retiree coverage) to help cover their cost-sharing requirements. Premiums for these policies can be costly, however, and even with supplemental insurance, beneficiaries can face out-of-pocket expenses in the form of copayments for services including physician visits and prescription drugs as well as costs for services not covered by Medicare. Although Medicaid supplements Medicare for many low-income beneficiaries, not all beneficiaries with low incomes qualify for this additional support because they do not meet the asset test.

Because people on Medicare can face out-of-pocket costs on three fronts—cost sharing for Medicare-covered benefits, costs for non-covered services, and premiums for Medicare and supplemental coverage—it is important to take into account all of these amounts in assessing the total out-of-pocket spending burden among Medicare beneficiaries. Our prior research documented that many beneficiaries bear a considerable burden for health care spending, even with Medicare and supplemental insurance, and that health care spending is higher among older households compared to younger households.2

This new analysis builds on prior work to examine out-of-pocket spending among Medicare beneficiaries, including spending on health and long-term care services and insurance premiums, using the most current year of data available (2010) from a nationally representative survey of people on Medicare. It explores which types of services account for a relatively large share of out-of-pocket spending, which groups of beneficiaries are especially hard hit by high out-of-pocket costs for services and premiums, and trends in out-of-pocket spending on services and premiums between 2000 and 2010.

Data and Methods

The analysis is based on data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Cost and Use file from 2000 to 2010 (the most recent year of data available). The dataset includes detailed information on Medicare-covered and non-covered services, utilization, and spending, including spending by Medicare, Medicaid, third-party payers, and out-of-pocket payments by beneficiaries. The types of services included in the MCBS are dental, home health, inpatient hospital, long-term care facility, medical providers and supplies, outpatient hospital, prescription drugs, and skilled nursing facility. The MCBS does not include spending and use for personal care services and supports, which can be a significant expense for people on Medicare who require long-term services and supports (LTSS) in the community. Therefore, any out-of-pocket spending on personal care and support delivered in the home or the value of unpaid personal care and support services is not included in the out-of-pocket spending estimate for home health services.

The analysis excludes beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, totaling 10.8 million or 22 percent of the 48.4 million Medicare beneficiaries represented in the 2010 MCBS, because the MCBS does not include reliable utilization and out-of-pocket spending data for this population, which would introduce significant bias if this population was included in the analysis.

To estimate total out-of-pocket spending per beneficiary in traditional Medicare, including premiums and services, we calculate for each sample person the sum of out-of-pocket spending on insurance premiums for Medicare Parts A and B and supplemental insurance coverage and medical and long-term care services reported in the MCBS. These amounts are averaged across the entire sample of traditional Medicare beneficiaries and weighted to be representative of the traditional Medicare beneficiary population or specific subgroups of beneficiaries. References to “total out-of-pocket spending” in this analysis always include both premiums and service spending. We also often refer to the separate components of total spending (either out-of-pocket spending on services or premiums) in presenting results.

For analysis of high out-of-pocket spending, we divide traditional Medicare beneficiaries’ total out-of-pocket spending (including services and premiums) into quartiles and deciles, and estimate the share of beneficiaries overall and by subgroup who have spending in the top quartile and top decile of total out-of-pocket spending. For a more detailed discussion of methods, data, and limitations, see Methodology.

Key Findings

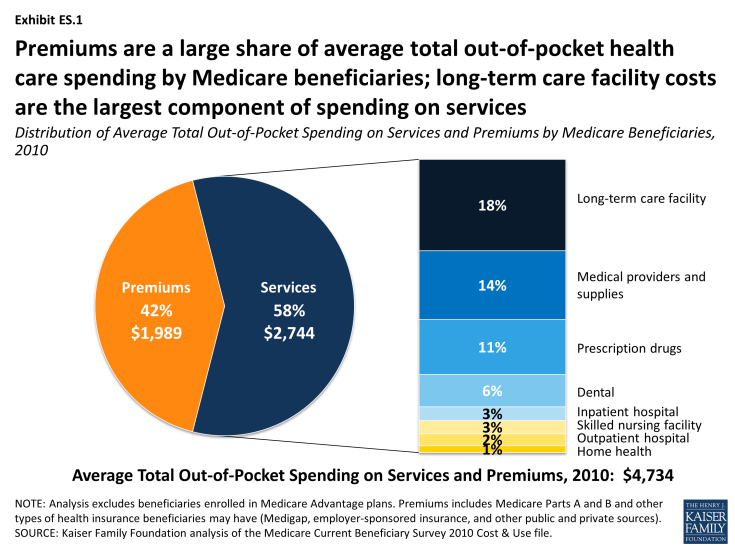

In 2010, Medicare beneficiaries spent $4,734 out of their own pockets for health care spending, on average, including premiums for Medicare and other types of supplemental insurance and costs incurred for medical and long-term care services.

- Premiums for Medicare and supplemental insurance accounted for 42 percent of average total out-of-pocket spending among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare in 2010 (Exhibit ES.1).

- Of the remaining 58 percent of average total out-of-pocket spending on services, long-term facility costs are the largest component (accounting for 18 percent of total out-of-pocket spending), followed by medical providers/supplies (14%), prescription drugs (11%), and dental care (6%). Neither long-term care services and supports nor dental services are covered by Medicare.

Out-of-pocket spending rises with age among beneficiaries ages 65 and older and is higher for women than men, especially among those ages 85 and older.

- Out-of-pocket spending tends to increase with age; in 2010, beneficiaries ages 85 and older spent three times more out-of-pocket on services, on average, than beneficiaries ages 65 to 74 ($5,962 vs. $1,926).

- On average, women on Medicare pay more out of pocket for services and premiums combined than men on Medicare ($5,036 vs. $4,363, respectively, in 2010), and this difference grows somewhat wider with age. Women ages 85 and over spent an average of $8,574 in 2010 on services and premiums while men ages 85 and over spent an average of $7,399 in total. This difference is primarily attributable to higher long-term care facility costs among older women.

As might be expected, beneficiaries in poorer health, who typically need and use more medical and long-term care services, have higher out-of-pocket costs, on average. This is the case whether measured by self-reported health status, number of chronic conditions or limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs), or use of services, such as hospitalizations, post-acute care, and long-term care.

- Average out-of-pocket spending on services rises as beneficiaries’ health status declines, and rises with the number of functional impairments and chronic conditions. For example, average out-of-pocket spending on services by beneficiaries in poor self-reported health was 2.5 times greater than among beneficiaries who said they were in excellent health ($4,505 vs. $1,774, respectively, in 2010). Similarly, beneficiaries with three or more ADL limitations spent five times more on services as those with no ADLs or IADLs in 2010 ($7,737 vs. $1,528, on average).

- Beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have relatively high out-of-pocket spending on services compared to beneficiaries with certain other conditions ($8,305, $5,841 and $5,439, respectively, on average in 2010), but their higher costs are driven by use of different types of services. For example, for people with Alzheimer’s disease, long-term care facility costs accounted for a majority of their average out-of-pocket costs in 2010, while those with ESRD faced higher out-of-pocket costs for medical services.

Just as Medicare spends more on beneficiaries who use more Medicare-covered services, more extensive use of services leads to higher out-of-pocket spending. This is especially true for beneficiaries who have multiple hospitalizations and post-acute care use and those who live in long-term care facilities.

- Average out-of-pocket spending on services rises with the number of hospitalizations; Medicare beneficiaries with one hospitalization in 2010 paid $4,475 out of pocket on services, on average, while those with two or more hospitalizations paid $6,216.

- Patients with a hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge spent roughly $1,200 more on services than those with only one inpatient stay in 2010 ($5,687 vs. $4,475, respectively, on average), including higher spending for medical providers and supplies, inpatient hospital services, and skilled nursing facility (SNF) services.

- Among beneficiaries who were hospitalized in 2010, those who received post-acute care in a SNF had significantly higher out-of-pocket spending on services than those who were discharged without SNF care ($9,508 vs. $3,645, respectively, on average); this was especially the case for long-term care facility residents with an inpatient stay and post-acute SNF care. Among beneficiaries with an inpatient stay followed by a skilled nursing facility stay, average out-of-pocket spending on SNF services was seven times greater among facility residents ($4,258) than among community residents ($595) in 2010.

- The small share of beneficiaries who live in long-term care facilities face significantly higher out-of-pocket spending on medical and long-term care services than those in the community (averaging $17,534 and $1,858, respectively, in 2010). While most of their spending on services is for long-term care facility expenses, facility residents also incur higher costs for inpatient hospital and post-acute care services than beneficiaries living in the community.

Spending on premiums, a significant component of total out-of-pocket spending among Medicare beneficiaries, varies less across subgroups of the Medicare population than spending on services. Unlike out-of-pocket spending on services, premium spending does not vary by health status or utilization, though it does vary somewhat by age, income, and source of supplemental coverage.

- While there is little variation in premiums among those ages 65 and over, premiums tend to be lower for beneficiaries under age 65 than among beneficiaries ages 65 and over, on average. This is most likely related to the fact that a relatively large share of Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 is also covered by Medicaid and thus not liable for premiums.

- Average premiums are generally similar for beneficiaries with incomes above $20,000, but lower for beneficiaries with lower incomes, most likely due to three factors: 1) lower-income beneficiaries with Medicaid typically do not pay premiums; 2) lower-income beneficiaries with full Medicaid benefits have little need for supplemental coverage; and 3) lower-income beneficiaries without Medicaid may not be able to afford supplemental insurance.

- Among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, those with a Medigap supplemental insurance policy pay more in premiums for this additional coverage, on average, than beneficiaries with employer-sponsored retiree health benefits ($2,166 vs $1,335, on average, in 2010). Not surprisingly, premiums are considerably lower for beneficiaries with Medicaid and those with no supplemental coverage.

Analysis of ‘high out-of-pocket spenders’ finds a disproportionate share of certain groups, including older women, beneficiaries living in long-term care facilities, those with Alzheimer’s disease and ESRD, and beneficiaries who were hospitalized, in the top quartile and top decile of total out-of-pocket spending (including both services and premiums). In 2010, one in four beneficiaries spent at least $5,244 out of pocket on medical and long-term care services and premiums (the top quartile), and one in ten spent at least $8,235 (the top decile). Average total out-of-pocket spending among the top quartile—$11,530 in 2010—was more than twice as much as the average among all beneficiaries ($4,734), while among the top decile, it was four times as much ($19,236).

- Long-term care facility costs are a major component of spending for beneficiaries in the top quartile of total out-of-pocket spending, accounting for more than one-fourth of their average out-of-pocket spending in 2010; indeed, seven out of ten beneficiaries living in long-term care facilities are in the top quartile. But it is not just long-term care facility spending that drives higher out-of-pocket costs; higher spending on medical providers and supplies, prescription drugs, and dental services also contribute to relatively high spending among those in the top quartile.

- Overall, four in ten women ages 85 and older are in the top quartile of total out-of-pocket spending on services and premiums, compared to only one-third of men ages 85 and older. These differences are attenuated but not eliminated when looking at out-of-pocket spending among community residents only.

- A disproportionate share of beneficiaries ages 85 and older are in both the top quartile and decile of total spending on services and premiums, compared to younger beneficiaries. Nearly four in ten beneficiaries ages 85 and older are in the top quartile versus just over two in ten of those ages 65-74.

- More than four in ten beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and ESRD were in the top quartile of total out-of-pocket spending in 2010, and nearly four in ten with Parkinson’s disease.

- Close to half of beneficiaries with two or more hospitalizations (45%) and more than half of those with an inpatient stay and a SNF stay (54%) were in the top quartile of total out-of-pocket spending in 2010.

Between 2000 and 2010, average total out-of-pocket spending among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare increased from $3,293 to $4,734, a 44 percent increase.

- During this period, total out-of-pocket costs increased at an average annual growth rate of 3.7 percent; the average annual growth rate between 2000 and 2010 was higher for premiums (5.8%) than for services (2.4%).

- Over these years, the average annual growth rate in out-of-pocket spending fluctuated, but trended down after 2006. Total out-of-pocket spending among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare grew at an average annual rate of 5.0 percent between 2000 and 2006, but fell to 1.8 percent between 2006 and 2010. This downward trend in the annual rate of growth in average total out-of-pocket spending also applies to both services and premiums. Out-of-pocket spending on services increased at an average annual growth rate of 3.5 percent between 2000 and 2006, but this growth rate dropped to 0.9 percent between 2006 and 2010; for premiums, the average annual growth rate decreased from 7.6 percent between 2000 and 2006 to 3.2 percent between 2006 and 2010.

Implications

The typical person on Medicare in 2010 paid about $4,700 out of pocket in premiums, cost sharing for Medicare-covered benefits, and costs for services not covered by Medicare. Even with financial protections provided by Medicare and supplemental insurance, some groups of Medicare beneficiaries incurred significantly higher out-of-pocket spending than others, which could pose challenges for those living on fixed or modest incomes. Out-of-pocket spending tends to rise with age and number of chronic conditions and functional impairments, and is greater for beneficiaries with one or more hospitalizations, particularly those who receive post-acute care.

Efforts to prevent unnecessary hospitalizations and readmissions and improve the coordination of post-acute care could not only help to reduce Medicare spending but also help to reduce out-of-pocket spending among beneficiaries with the greatest needs. Monitoring trends in out-of-pocket spending among people on Medicare in the coming years will be important in understanding whether such efforts are making a difference.