2013 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2013 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health is the fifth in a series of surveys designed, conducted, and analyzed by the Kaiser Family Foundation in order to shed light on the American public’s perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes about the role of the United States in efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. This latest survey updates trends from Kaiser’s previous surveys dating back to 2009, and explores new questions including the public’s perception of the “bang for the buck” of U.S. aid and its ability to promote self-sufficiency in developing countries, views of spending reductions in the context of the federal budget deficit, and more detail on people’s sources of information, including how much news they report hearing about specific global health issues. For the first time, the survey also includes some more detailed questions on perceptions and awareness of polio.

A few key highlights from the survey are described here, and a more detailed set of findings and charts can be found below.

Summary Of Key Findings

As the country continues to climb out of economic recession and policymakers battle over the federal budget and national debt, Americans’ basic level of support for current levels of U.S. spending on efforts to improve health for people in developing countries has held relatively steady in recent years. Six in ten say the country spends either too little or about the right amount on such efforts, while three in ten say we spend too much. While there are some partisan differences in attitudes towards U.S. global health spending, these differences are much smaller than other surveys have found on questions of domestic health care policy.

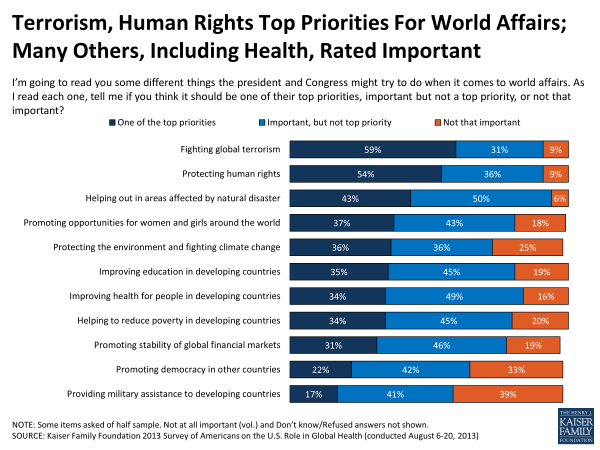

Improving health in developing countries is one of many priorities the public sees as important for the President and Congress to address in world affairs, but not the top one. Fighting terrorism tops the list of priorities, followed by protecting human rights and helping out in areas affected by natural disasters.

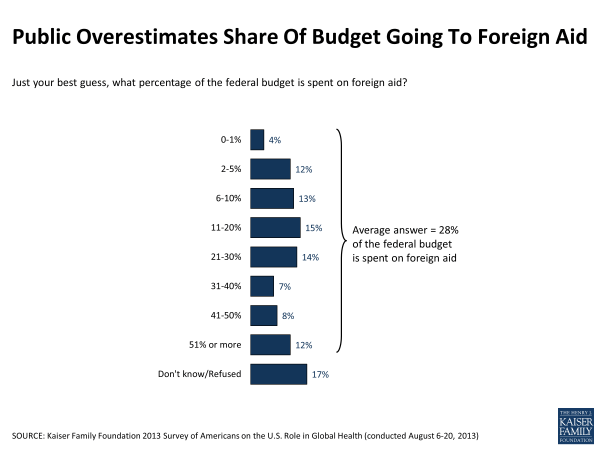

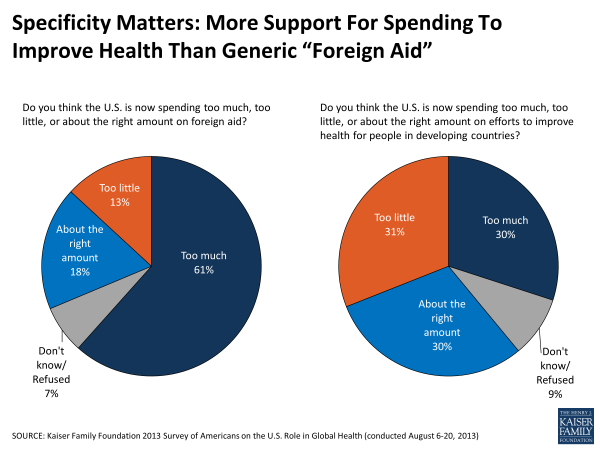

As previous Kaiser surveys have found, misperceptions persist about the size of U.S. foreign aid and how aid is directed. On average, Americans think 28 percent of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid, when it is about 1 percent. Further, four in ten think a major part of U.S. foreign aid is given directly to developing countries to use as they see fit, when in reality most U.S. aid is directed to specific program areas. As we’ve seen in the past, people are more supportive of foreign aid spending when a specific purpose is mentioned – in this case, improving the health of people in developing countries – than they are of the idea of foreign aid in general.

There are several important caveats to Americans’ support for U.S. global health spending. Current economic conditions make people wary of increasing spending abroad, and when it comes to contributing to deficit reduction, larger shares of the public support cuts in overseas aid compared with domestic programs like Medicare, Medicaid, public education, and Social Security. Further, most Americans do not think U.S. aid aimed at improving health delivers a good “bang for the buck,” and only about a third think it increases self-sufficiency in developing countries.

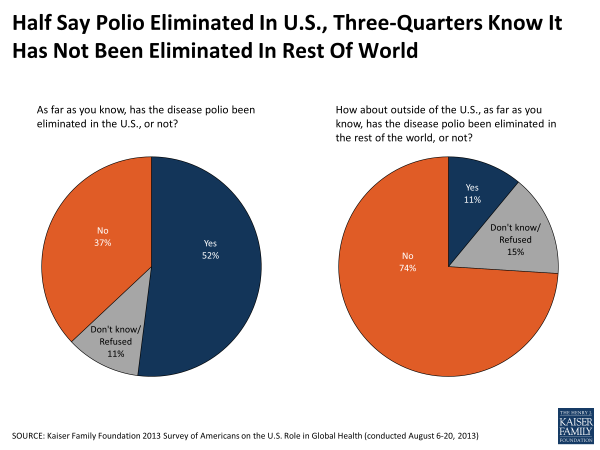

An ongoing challenge for those looking to increase the public’s level of interest in and support of global health is grabbing their attention, and there are some signs that the visibility of global health issues has declined in recent years. News media continues to be the public’s top source of information on global health, and there is great variation in how much people report hearing in the news about specific health issues in developing countries, with hunger and malnutrition at the top of the list. Few say they’ve heard much about tuberculosis or polio from the news media. Still, public awareness of the global challenge of polio is high; three-quarters are aware that the disease has not been eradicated worldwide.

Priorities For U.S. In World Affairs, Priorities Within Global Health

Terrorism, Human Rights Top Public’s Priorities For U.S. In World Affairs

Improving health in developing countries is one of many priorities the public sees as important for the president and Congress to address in world affairs. At the top of the public’s list, more than half see fighting global terrorism and protecting human rights as a top priority, followed by disaster relief. Following these are a cluster of issues seen as top priorities by more than a third of the public, including promoting opportunities for women and girls, protecting the environment and fighting climate change, improving education, improving health, and reducing poverty in developing countries. After two wars, these priorities rank higher for the public than promoting democracy and providing military assistance to developing countries.

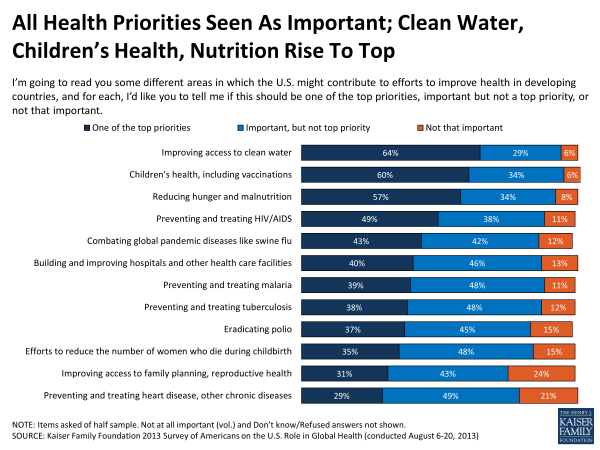

Within Health, All Priorities Seen As Important; Clean Water, Children’s Health, Hunger Rise To Top

When asked about a variety of different priorities for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries, large majorities believe each area is important, and between three and six in ten say each should be “one of the top” priorities. Highest on the list of those considered top priorities are basic needs such as improving access to clean water and reducing hunger, along with children’s health and vaccinations.

Given growing attention to polio eradication worldwide, this year’s survey included some more detailed questions about the disease. While eradicating polio does not rank high on the public’s list of priorities for U.S. involvement in improving health in developing countries, awareness of the global challenge of polio is relatively high. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of the public are aware that polio has not been eradicated around the world. Public awareness is somewhat less accurate when it comes to the status of the polio epidemic at home. About half (52 percent) are aware that the disease has been eliminated in the U.S., but nearly four in ten (37 percent) mistakenly believe it has not been eliminated in the U.S., and another one in ten (11 percent) are unsure.

Views Of U.S. Spending On Foreign Aid And Efforts To Improve Health In Developing Countries

Confusion About Foreign Aid Spending Persists; Providing Accurate Information Has The Potential To Change Views

Consistent with previous Kaiser polls, the 2013 survey finds that the vast majority of the public overestimates the size of the federal budget that is spent on foreign aid, with just four percent correctly saying that foreign aid makes up one percent or less of the federal budget. A majority give answers above 10 percent, and on average, Americans answer that 28 percent of the budget is spent on foreign aid.

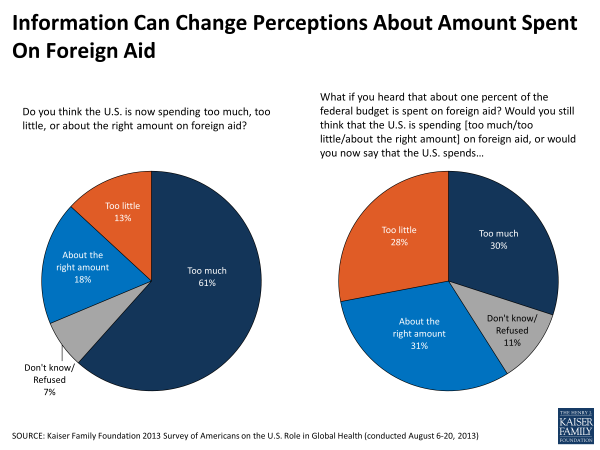

As previous Kaiser surveys have shown, spending on “foreign aid” continues to be unpopular, and in this survey, six in ten think the U.S. is now spending too much on foreign aid, and just 13 percent say the country is spending too little. However, we also find that providing people with accurate information has the potential to move opinion significantly. When survey respondents are told that only about one percent of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid, the share saying the U.S. spends too little more than doubles (from 13 percent to 28 percent), while the share saying we spend too much drops in half (from 61 percent to 30 percent).

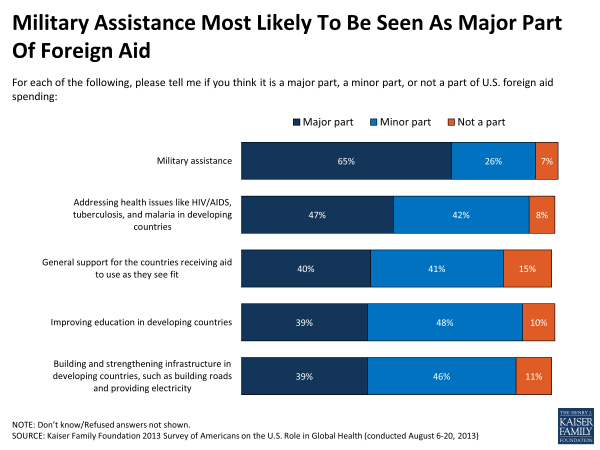

When it comes to the types of things U.S. foreign aid money is actually spent on, the public perceives a variety of components as making up this spending. At the top of the list, 65 percent think military assistance is a “major part” of U.S. foreign aid spending, and nearly half (47 percent) say the same about addressing health issues in developing countries. Around four in ten (39 percent) see improving education and building and strengthening infrastructure as major parts of U.S. foreign aid spending. In addition to these specific areas, 40 percent believe a major part of foreign aid is given to developing countries to use as they see fit. In fact, most U.S. foreign aid spending goes to specific program areas (such as agriculture, disease prevention, and maternal health, among others), and most aid does not go directly to governments, but rather to local or international non-governmental organizations, including to U.S.-run programs, in developing countries.1

Specificity Matters: More Support For Spending On “Improving Health” Versus “Foreign Aid”

Kaiser surveys have consistently found that Americans are more likely to support U.S. spending for global health specifically than they are when asked about foreign aid more generally. In the current survey, about six in ten say the U.S. is now spending too little (31 percent) or about the right amount (30 percent) on efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, while three in ten say the country is spending too much.

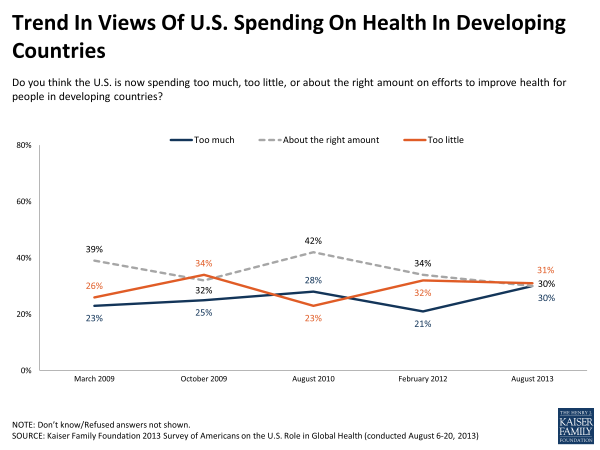

Attitudes towards the amount of U.S. spending on health in developing countries have held relatively steady in recent years over the course of the country’s economic recovery and battles over the federal budget and deficit. The share who say the U.S. is spending “too much” on these efforts is somewhat higher in 2013 than it was in 2012, but is close to the level measured in 2010.

Public Believes U.S. Global Health Spending Protects Health At Home And Improves U.S. Image, But Moral Reason For Giving Trumps Self-Interest

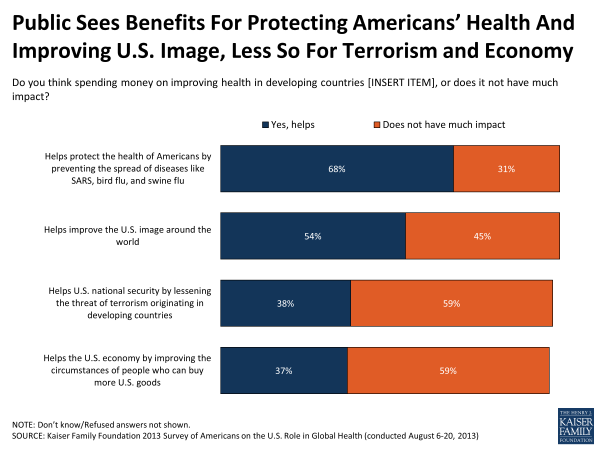

Nearly seven in ten believe that U.S. spending on health in developing countries helps protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases, and over half believe such spending is helpful for improving the U.S. image around the world. The public is somewhat less convinced that U.S. global health spending helps U.S. national security or the U.S. economy, with close to four in ten saying it is helpful in these areas and about six in ten saying it doesn’t have much impact.

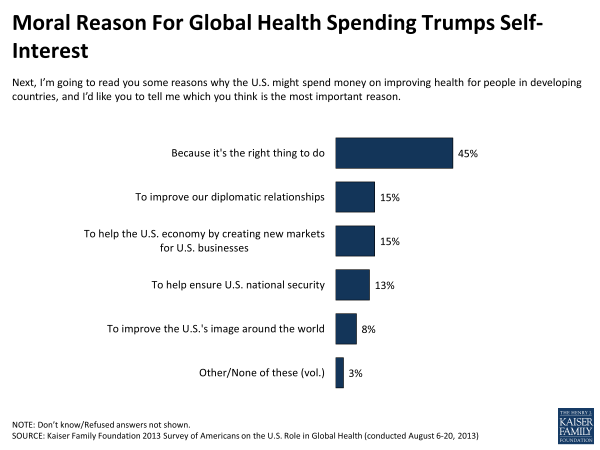

While many recognize these potential benefits at home, the moral argument ranks higher than self-interest arguments among the public in terms of reasons for giving aid. Nearly half say the most important reason for the U.S. to spend money on improving health in developing countries is “because it’s the right thing to do,” while far fewer choose reasons related to U.S. diplomacy, economy, or security.

Most Support Participation In International Efforts

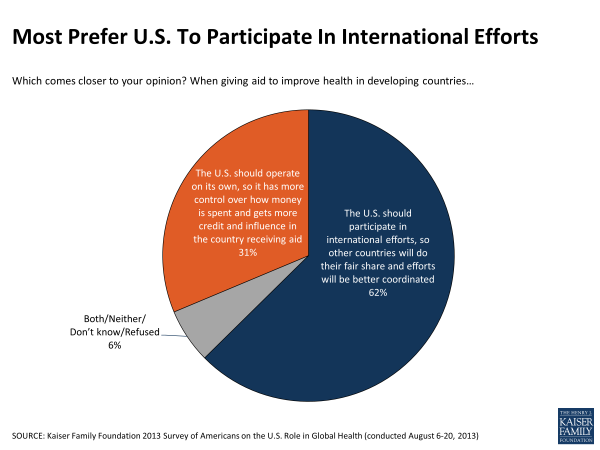

When it comes to how the U.S. should go about providing aid to improve health in developing countries, over six in ten say the country should participate in international efforts, so other countries will do their fair share and efforts will be better coordinated. About half as many (31 percent) feel that it’s better for the U.S. to operate on its own, so we have more control over how money is spent and get more credit and influence in the countries receiving aid. This desire to participate in international efforts may be related to the fact that half of Americans believe the U.S. is already contributing more than its fair share to global health efforts compared to other wealthier countries, while just 13 percent think the U.S. is doing less than its fair share and three in ten say the U.S. share is about right.

Caveats To Support For Spending; Perceived Barriers

Caveats To Support For Current Level Of U.S. Spending On Global Health: Concerns About Economy, Desire To Protect Domestic Programs, Skepticism About Whether Spending Will Lead To Progress

While six in ten Americans say that the current level of U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries is either too low or about right, economic concerns continue to make the public wary of the idea of increasing spending abroad. Since 2009, a solid majority of the public has said that given the serious economic problems facing the country and the world, the U.S. can’t afford to spend more money on health in developing countries, while a much smaller share have said the current economic conditions make it more important than ever for the U.S. to increase such spending.

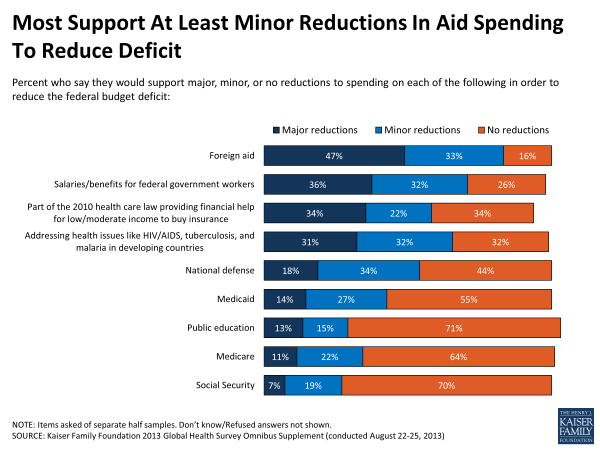

Another important caveat to support for current levels of spending is that the public is much more likely to back reductions in spending on overseas aid in order to reduce the deficit than they are to support cuts in domestic programs like Medicare, Social Security, and public education. Nearly half say they would support major reductions to spending on foreign aid as a way to reduce the federal budget deficit, and another third would support minor reductions. While fewer say they would support major reductions in “spending to address health issues like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria in developing countries” versus the generic “foreign aid,” still over six in ten support major or minor reductions. By contrast, more than half say they would support no reductions to spending on public education, Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid in order to reduce the deficit.

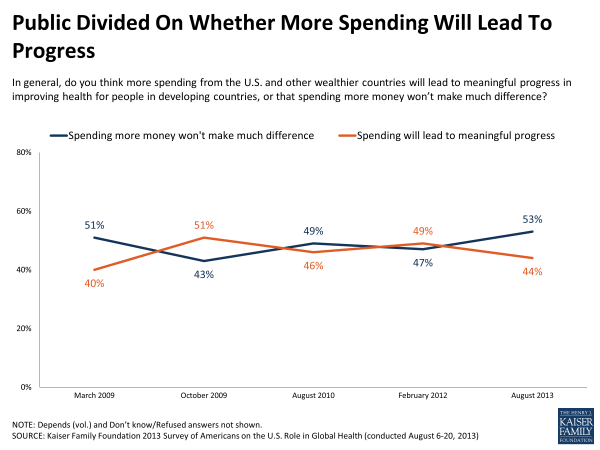

Since 2009, the public has also been divided as to whether more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health in developing countries or won’t make much difference. In 2013, 44 percent believe spending will lead to progress, while just over half say it won’t make much difference.

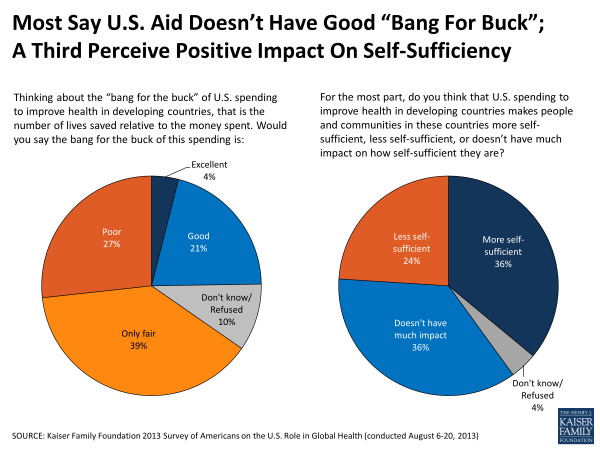

Skepticism about whether spending will lead to progress may be related to the fact that most Americans don’t believe U.S. spending on health in developing countries delivers a good return on investment, and only about a third think it improves self-sufficiency.

Two-thirds of the public rates the “bang for the buck” of U.S. spending on health in developing countries as “only fair” or “poor,”, while just a quarter say it is “good” or “excellent.” And while just over a third of the public believes such spending helps make people and communities more self-sufficient, an equal share believes this type of aid doesn’t have much impact on self-sufficiency, and roughly a quarter say it decreases self-sufficiency.

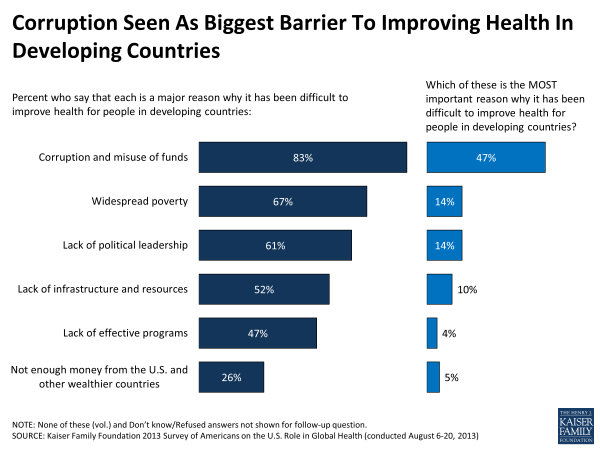

Corruption Perceived As Biggest Barrier To Progress

Another finding that has been consistent in Kaiser surveys: The public sees corruption as the biggest barrier to progress on global health. In the latest survey, 83 percent say corruption and misuse of funds is a “major reason” why it has been difficult to improve health for people in developing countries, and nearly half say it is the most important reason. Perhaps because of this concern about corruption, two-thirds of the public (66 percent) think the U.S. should have the primary role in determining how U.S. aid is spent in developing countries to ensure tax dollars are well spent, while just about a quarter (27 percent) say it’s better for the developing country governments to make decisions about how aid is spent since they know their country’s problems best.

Section 4: Attitudes Towards U.S. Global Health Spending By Party Identification

As is the case when it comes to most questions involving federal spending, attitudes towards U.S. spending on efforts to improve health in developing countries differ somewhat by individual political party identification. However, these partisan differences are much smaller than we find on questions of domestic health care policy and spending. For example, Republicans are 15 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say the U.S. currently spends too much on health in developing countries, but still over half of Democrats, Republicans, and independents say such spending is either too little or about right.

| FIGURE 17: VIEWS OF CURRENT LEVELS OF U.S. GLOBAL HEALTH SPENDING BY PARTY ID | ||||

|

Total

|

Democrats

|

Independents

|

Republicans

|

|

| Do you think the U.S. is now spending too much, too little, or about the right amount on efforts to improve health for people in developing countries? | ||||

| Too much |

30%

|

24%

|

30%

|

39%

|

| About right |

30

|

29

|

31

|

32

|

| Too little |

31

|

40

|

30

|

20

|

| TOTAL TOO LITTLE OR ABOUT RIGHT |

61

|

69

|

61

|

52

|

Some underlying partisan differences in perceptions of the impact of U.S. spending on health in developing countries may help explain the small but measurable differences in support for spending. For example, while a majority of Democrats believe that more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health, two-thirds of Republicans feel that more spending won’t make much difference. Democrats are also more likely than Republicans to believe that U.S. aid helps people and communities in developing countries to become more self-sufficient, while Republicans are more likely to perceive a negative impact on self-sufficiency. Republicans and independents are more likely to believe U.S. spending on health in developing countries delivers a “poor” bang for the buck, though even among Democrats, relatively few see such spending as offering a good return on investment.

| FIGURE 18: VIEWS OF IMPACTS OF U.S. GLOBAL HEALTH SPENDING BY PARTY ID | ||||

|

Total

|

Democrats

|

Independents

|

Republicans

|

|

| In general, do you think more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health for people in developing countries, or that spending more money won’t make much difference? | ||||

| Will lead to meaningful progress |

44%

|

55%

|

45%

|

31%

|

| Won’t make much difference |

53

|

42

|

53

|

67

|

| For the most part, do you think that U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries makes people and communities in these countries more self-sufficient, makes them less self-sufficient, or doesn’t have much impact on how self-sufficient they are? | ||||

| More self-sufficient |

36

|

44

|

36

|

30

|

| Less self-sufficient |

24

|

20

|

25

|

29

|

| Doesn’t have much impact on self-sufficiency |

36

|

33

|

36

|

39

|

| Next, thinking about the “bang for the buck” of U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries, that is the number of lives saved relative to the money spent. Would you say the bang for the buck of this spending is…? | ||||

| Excellent |

4

|

6

|

3

|

2

|

| Good |

21

|

23

|

24

|

16

|

| Only fair |

39

|

42

|

37

|

41

|

| Poor |

27

|

20

|

28

|

33

|

Visibility Of Global Health Issues And Sources Of Information

Declining Attention And Visibility Of Global Health Issues

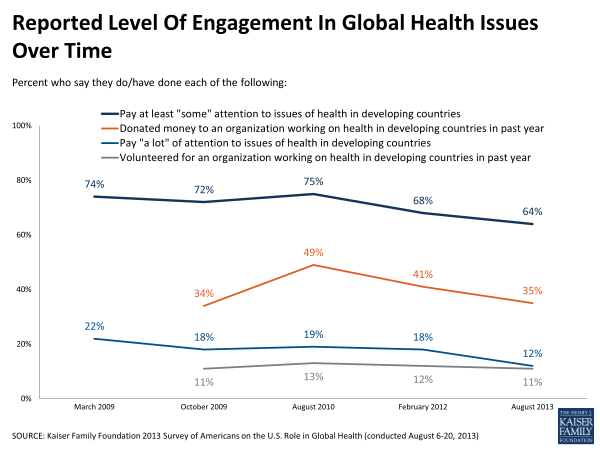

The public reports engaging in global health issues on various levels, but there is some indication that the level of visibility and attention has declined somewhat in recent years. In 2013, close to two-thirds of the public say they pay at least “some” attention to issues of health in developing countries, but just 12 percent say they pay “a lot” of attention. Each of these shares is down 10 percentage points from March 2009. About a third of the public reports having donated to an organization working on global health issues in the past year, down from a high of 49 percent in August 2010 (the year of the Haiti earthquake), and similar to the level measured in 2009. Eleven percent say they have volunteered for an organization working on health in developing countries in the past year, a share that has held steady since 2009.

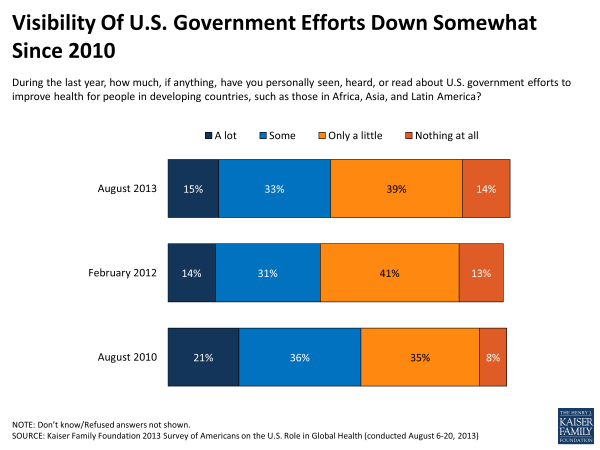

Over half of the public reports hearing “only a little” or “nothing at all” about U.S. government efforts to improve health in developing countries over the past year, while a third say they’ve heard “some” and just 15 percent say they’ve heard “a lot.” Visibility of U.S. government efforts in this area are similar to 2012, but still somewhat lower than 2010, when more than half said they had heard “a lot” or “some” about these efforts.

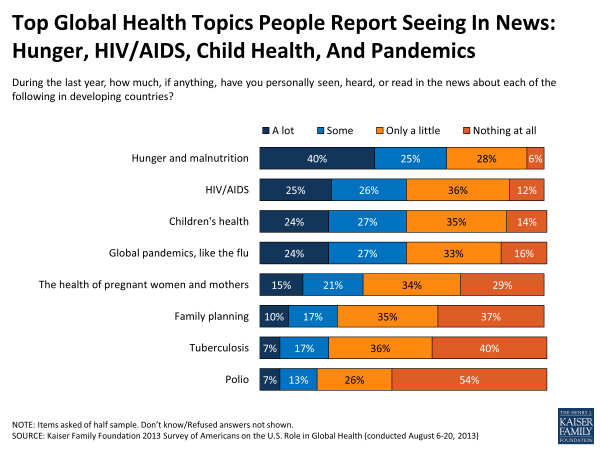

U.S. government efforts, there is variation in how much the public reports hearing in the news about specific global health issues and problems. Most prominently, nearly two-thirds say they have heard “a lot” or “some” in the past year about hunger and malnutrition in developing countries. Just over half report hearing news about HIV/AIDS, children’s health, and global pandemics like the flu, while somewhat fewer report hearing something about maternal health. Less visible issues include family planning, tuberculosis, and polio.

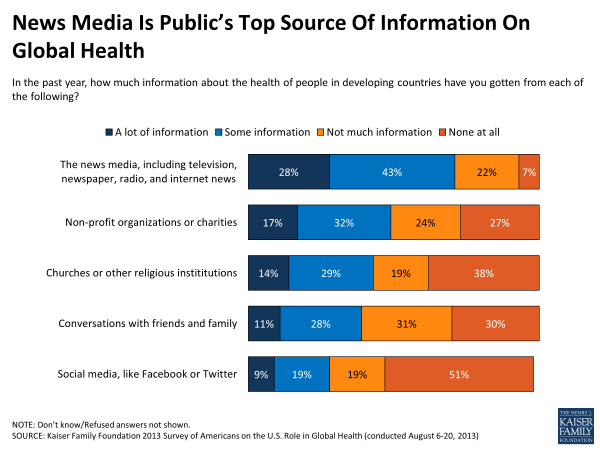

News Media Top Source Of Information

As it is on many topics, the news media remains the public’s top source of information on global health, with seven in ten saying they have gotten “a lot” or “some” information about the health of people in developing countries from news media sources in the past year. Behind the media as sources of information are non-profit organizations, churches and other religious institutions, and conversations with friends and family. Social media ranks at the bottom of the list as a source of information, with just 28 percent saying they’ve gotten “a lot” or “some” information about health in developing countries from sites like Facebook or Twitter in the past year. Young adults are somewhat more likely than others to report getting information about global health from social media (47 percent of those ages 18-29 say they’ve gotten at least “some” in the past year), but news media is still the top source, far outranking social media for Americans of all ages.

With the news media as their top source of information on issues of health in developing countries, many Americans say they would like to hear more from this source. Fully half say the news media spends too little time covering global health issues, while just 12 percent say the news media spends too much time on the topic and a third say the amount of coverage is about right. When it comes to the content of that coverage, Americans report hearing a fairly even mix of positive and negative stories. Overall, 28 percent say they’ve heard only or mostly positive news stories about global health in the past year (such as stories about successful programs), and a similar share – 26 percent – say they’ve heard only or mostly negative stories (such as those about corruption).

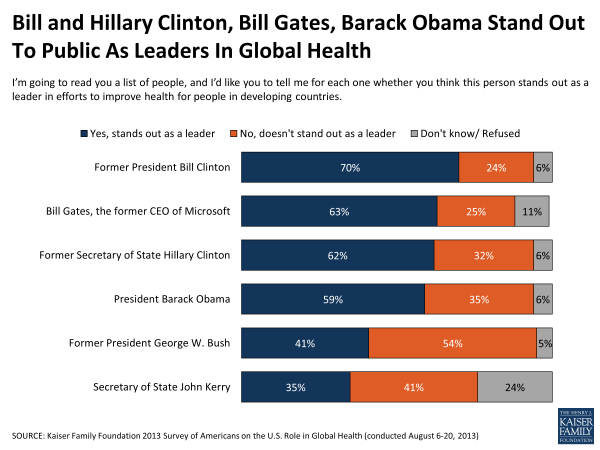

Bill And Hillary Clinton, Bill Gates, And Barack Obama Stand Out As Leaders In Global Health

When asked about various people who might be perceived as leaders in efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, Bill Clinton tops the list, with 70 percent saying the former president stands out as a leader in this area. He is followed closely by philanthropist and former Microsoft CEO Bill Gates, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and President Barack Obama. Fewer see former president George W. Bush or current Secretary of State John Kerry as leaders in global health.