Shaping the U.S. Global Health Policy Agenda: Key Considerations for the Future

As we enter the last two years of President Obama’s final term, with a newly reshaped Congress after the mid-term elections, what is in store for U.S. global health policy? What are the key issues in need of attention and will they be addressed now or have to await the arrival of a new President 2017? Will the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa change the equation? Here’s our pick of eight questions that together, are likely to shape the future of the U.S. response.

How Should the U.S. Balance a Shifting Burden of Disease with the Unfinished MDG Agenda? Currently, U.S. global health programs are squarely targeted on traditional global health challenges – the “MDG agenda” of tackling major communicable diseases such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis, and maternal and child health and family planning and reproductive health – even as new global health challenges have emerged and the global burden of disease has shifted. While the traditional agenda still represents the primary health challenges facing the region of sub-Saharan Africa and some of the poorest countries around the world, in all other regions, the most pressing health challenges come primarily from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. This shifting burden has led some to call for more U.S. investment in global NCD efforts while others have worried that such investments could come at the expense of the remaining global health agenda and the poorest of the poor. These questions and the pressure to pivot U.S. programs and funding will likely become even more pronounced as the global community moves into the post-2015 era and the burden of disease continues to shift even further.

What Can We Learn from Ebola? The biggest global health story of 2014 took everyone by surprise: an epidemic of Ebola (primarily in three West African countries) that quickly grew to a truly unprecedented size. The epidemic spilled across national and regional borders, generating fear and, eventually, a global response including sizeable financial and personnel contributions from the U.S. government. Many have pointed to the lack of investment in health systems in the highly affected countries as being the key reason for the spread of Ebola there and the subsequent global repercussions. Until now, U.S. investments in and programmatic focus on strengthening health systems, especially the kinds of basic public health capabilities that would help address emerging health threats such as Ebola, have been fairly meager. Recognizing that country capacity for preventing, detecting and responding to emerging threats was limited, the U.S. did launch a new effort earlier this year (and before anyone was talking about Ebola in West Africa) called the Global Health Security Agenda to bolster these capacities along with 30 partner countries. Will recent events end up having a lasting effect on the U.S. Global Health Security Agenda, and on U.S. support for strengthening health systems? Will the emergency Ebola funding included in the FY2015 budget support GHSA objectives, and will it translate into meaningful progress on improving basic public health capabilities in the developing world?

Who Will Lead the U.S. Response? When President Obama first took office, he created the Global Health Initiative (GHI), intended to foster “a more integrated approach to fighting diseases, improving health, and strengthening health systems”, and provide a comprehensive U.S. government strategy for global health. The GHI also sought to move toward a more centralized governance and leadership structure for U.S. global health programs. These steps were based on the Administration’s diagnosis that the U.S. approach to global health had become overly siloed, with programs funded, implemented, and evaluated along separate, parallel lines. However, after several years of halting progress and intra-agency tensions, the GHI was effectively abandoned in 2012, and its overall legacy is decidedly mixed. At this point, the structure of U.S. global health programs has returned in large part to its pre-GHI state, and there is no clear leadership structure. With no real overarching leader for U.S. global health programs, who will drive the agenda going forward?

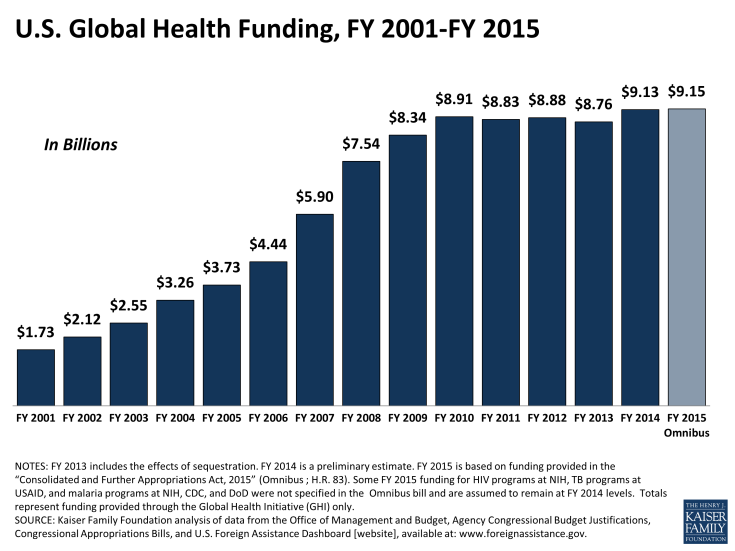

Will Funding Rise to Meet Global Health Priorities? The economic crisis of 2008 and subsequent recession ushered in an era of federal budget austerity, which in turn affected funding for global health. Following a decade of remarkable growth, U.S. global health funding began to level off after 2010 (see graph), though it generally has fared better than some other sectors. The FY 2015 budget bill just introduced in Congress continues this trend, maintaining overall global health funding at current levels. Still, within an essentially fixed budget, this has meant that current priorities have sometimes had to compete with one another and there is little room for funding new or expanded programs, resulting in an increasingly zero sum game. Looking ahead, the fiscal environment is likely to get even tighter in the new Congress. What will this mean for the future of U.S. global health programs, especially with continuing, and in some cases growing, unmet needs? Will funding for global health continue to do relatively well, compared to other sectors?

Will Bipartisanship be Sustained? Support from Democrats and Republicans alike has been one of the hallmarks of U.S. global health policy, most notably seen in PEPFAR, first created by President Bush in 2003, and reauthorized twice by Congress on a bipartisan basis, including in 2008 and again in 2013, the latter being a time when few other pieces of legislation were passed. In addition, as noted above, even though global health funding has plateaued, it has fared relatively well compared to some other areas because of bipartisan support. And even issues that have historically been caught in the partisan crossfire, such as family planning, have also benefited from some bipartisan support. With the loss of some key Congressional global health champions on both sides of the aisle in recent years, including in the most recent election, it is not yet clear how global health will fare.

How Will the U.S. Manage Country Transitions and “Graduation” from U.S. Assistance? Countries receiving U.S. global health assistance have experienced enormous income and demographic changes over the last several decades. In the past decade alone, more than 30 countries have transitioned from low to middle-income status and many others are on the cusp of making such a transition. Today, the majority of the global poor now live in middle-income countries rather than low income ones. In addition, many countries that have historically been aid recipients are increasingly able to use domestic resources to respond to their health needs. As such, global health donors, including the Global Fund, GAVI, and the U.S., are struggling to adjust to these broad trends, and face many challenges to moving in this direction. These include how best and when to begin transferring financial and technical oversight of global health programs to country partners, including civil society; how to ensure that country progress in health is not negatively affected with a reduction in U.S. support; and how to address health inequities that may persist – or reach populations whose needs may not be being met by their government – in countries that otherwise would be candidates for transitioning from U.S. support.

What is the Future of PEPFAR? PEPFAR is the largest health program in the world focused on a single disease and by far the largest program in the U.S. global health portfolio. It has been widely heralded as a major success, helping to stem the tide of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa and other hard hit areas. Now in its second decade, PEPFAR remains a cornerstone of the U.S. global health response and is expected to announce new global HIV targets next year. But there are ongoing questions and concerns about how it continues to work towards the goal of achieving an “AIDS Free Generation” in an era of shrinking resources, requiring it to “do more with less” while HIV needs remain significant and deep disparities persist for some populations and within some countries. In addition to resource constraints, other challenges facing the program include: how to continue to support a shift from an “emergency” response to a sustained, country-led model; how to strike the right balance in funding and programming between HIV treatment, prevention, and care, between bilateral HIV programs and the Global Fund, and between HIV and other parts of the U.S. global health portfolio; and how to set new, ambitious targets for the future.

How Should the U.S. Address the Links Between Human Rights & Health? Human rights and health are integrally linked. While promotion of human rights is a stated goal of U.S. foreign and national security policy, the link between human rights and health has only gained more attention within U.S. programs and policy recently. This has been driven by the experience of PEPFAR, which has sought to provide HIV interventions to many who are marginalized and stigmatized within their countries and communities, including men who have sex with men and sex workers, as well as the challenge of addressing gender-based violence among women. In addition, there has been growing awareness of the stigma, discrimination, and violence faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals, both within and outside of the health sector, which compromise their ability to access needed health services and can adversely affect health status. In many countries, including those that receive U.S. health and development assistance and/or are key strategic partners of the U.S., the barriers faced by LGBT individuals include discriminatory laws and policies. Recent actions to further criminalize same sex behavior and/or restrict the rights of LGBT persons and their supporters in several countries that are top aid recipients of U.S. support have raised questions about how the U.S. should respond, including whether the U.S. should suspend or redirect aid or implement new policies to govern its assistance.

Given the outsized role of the U.S. in global health, the way in which the U.S. addresses these key issues will have major implications not just for U.S. standing in the world but also for the future trajectory of global health. Key moments to watch will include ongoing negotiations on the budget, the start of the next Presidential campaign, and ultimately, the 2016 election.