Women’s Connections to the Healthcare Delivery System: Key Findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey

Introduction

Women’s ability to access the care they need depends greatly on the availability of high quality providers in their communities as well as their own knowledge about maintaining their health through routine checkups, screenings, and provider counseling. This brief presents findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey, a nationally representative survey of women ages 18 to 64 on their health status, relationships to regular providers and sites of care, and the frequency at which they receive routine preventive care. The Kaiser Family Foundation has conducted surveys on women’s health care in 2001, 2004, 2008, and 2013. This brief focuses on findings from the newest 2017 survey and presents some findings compared to earlier years.

Health Status

The vast majority of women report good or excellent health, but higher shares of older and poorer women experience health problems.

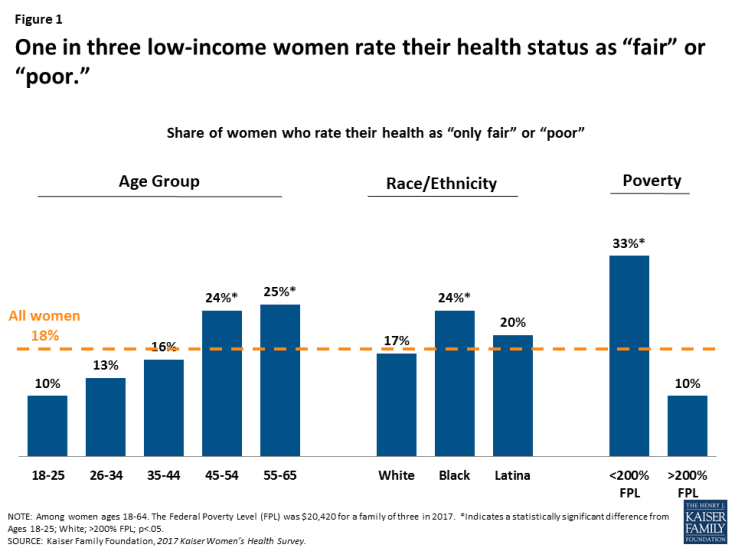

When asked to describe their own health, most women (82%) rate it positively (excellent, very good, or good). Conversely, almost one in five women (18%) describe their health as “only fair” or “poor.” As women age, they are more likely to rate their health as fair or poor. Higher shares of low-income women and Black women also report fair or poor health (Figure 1). A third of low-income women rate their health as fair or poor. Some of these women have high healthcare needs, yet they are more likely to lack coverage or the means to afford the care they require.

Many women are managing chronic conditions or living with disabilities that limit daily activities.

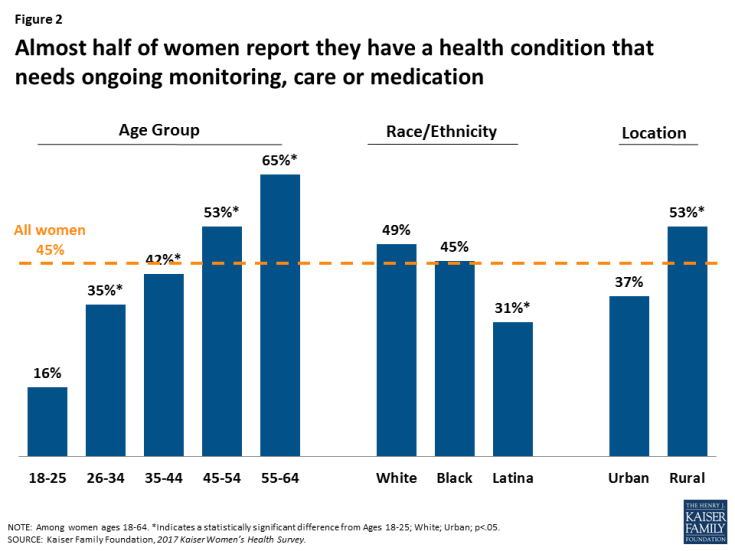

Nearly half of non-elderly adult women report they have a health condition that requires some degree of ongoing care, monitoring, or medication (Figure 2). This rate rises steadily with age, increasing to two-thirds (65%) of women ages 55-64.

Figure 2: Almost half of women report they have a health condition that needs ongoing monitoring, care or medication

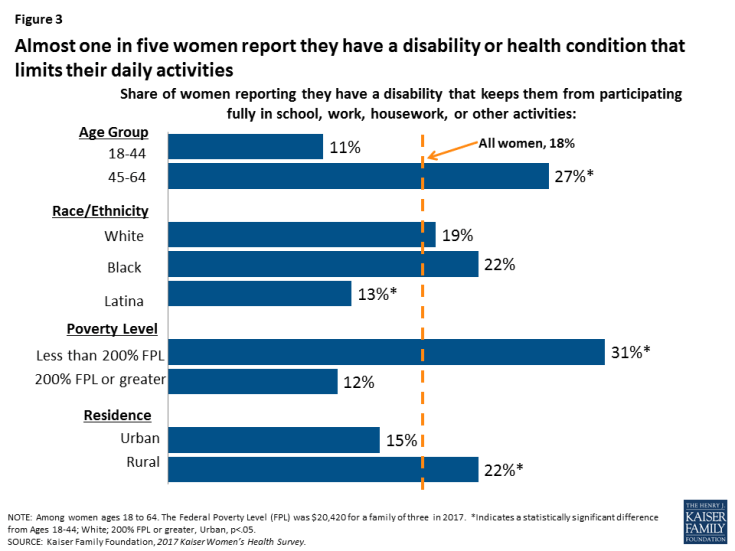

Almost one in five women (18%) say they have a disability or condition that keeps them from participating fully in work, school, or other activities (Figure 3). As with other health status indicators, this increases as women age and is more common among rural women (22%) compared to those who live in urban environments (15%).

Figure 3: Almost one in five women report they have a disability or health condition that limits their daily activities

Usual Source of Care

The vast majority of women have seen a medical provider in the past two years.

Nine in ten (90%) women have seen a doctor or provider in the past two years, remaining constant from 2013 (91%). However, fewer uninsured women (67%), Latina women (81%) and women with incomes less than 200% FPL (85%) have recent visits for medical care than the average (data not shown).

Eight in ten women report they have a usual place they go to and a clinician they see for care.

A usual source of care is associated with increased use of preventive care and better health outcomes. Eight in ten women report they have a usual place of care and a regular clinician they see for care (Table 1). Rates are higher among older women, rising to 90% among those ages 55 to 64. White and Black women also are more likely to identify a usual site of care or provider compared to Latina women. Most women with private insurance report a regular place (87%) or clinician (84%) they go to for care, as do women with Medicaid (84% and 78%, respectively). Uninsured women are much less likely to have stable connections to care, with just about half reporting they have a regular place (55%) and clinician (49%) for care.

| Table 1: Share of women who identify a regular place or clinician they go to for care, by selected characteristics | |||||||||||

| All Women | Age Group | Poverty Level | Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| 18-25 | 26-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | <200% FPL | ≥200% FPL | White | Black | Latina | ||

|

Share of women reporting a place they usually go to when they are sick or need advice about health

|

83% | 73% | 74% | 84%* | 88%* | 90%* | 79%* | 85% | 85% | 83% | 73%* |

| Share of women reporting a regular clinician they see for care | 79% | 64% | 69% | 82%* | 86%* | 90%* | 73%* | 83% | 82% | 86% | 66%* |

| NOTES: Among women ages 18-64. The Federal Poverty Level (FPL) was $20,420 for a family of three in 2017. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from 18-25, ≥200% FPL, White; p<.05. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. |

|||||||||||

About 46% of women have more than one provider (not including a dentist or mental health professional) they see on a regular basis. This is much less common among women age 18-25 (27%), Latina women (28%), and uninsured women (22%). The most common types of secondary providers are Ob-gyns (46%) and other medical specialists (33%).

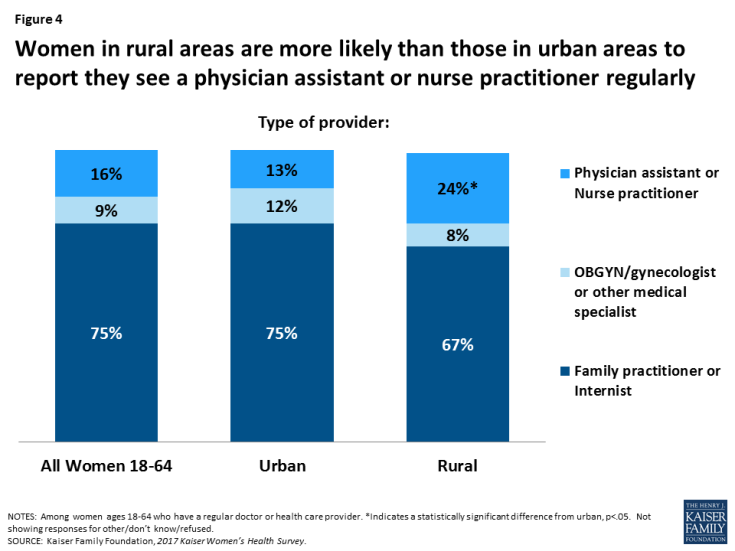

A higher share of women living in rural areas see a physician assistant or nurse practitioner for routine care than those living in urban communities. Most women who report having a regular provider say their provider is an internist or family practitioner (75%). This is true in all locales, but there are some differences. Nearly one in four (24%) women in rural settings say their regular provider is a physician assistant or nurse practitioner, compared to 13% of women who live in urban environments. (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Women in rural areas are more likely than those in urban areas to report they see a physician assistant or nurse practitioner regularly

About one in ten women reported they did not obtain care when they needed it because they lacked a regular provider or a provider would not accept her insurance plan.

While most women have a regular provider, over one in ten do not, which can hinder their ability to obtain timely care. Among uninsured women, a quarter (26%) stated they delayed or went without care because they did not have a regular provider (Table 2). This was also the case for 18% of women with Medicaid and 16% of Latinas. Younger women also reported this barrier at higher rates than older women. Younger women with insurance were also more likely to report trouble finding a provider that would take their insurance. Provider participation in Medicaid in some states is much lower than for private insurance, and nearly three in ten women (29%) with Medicaid stated they had difficulty finding a provider that would accept their coverage.

| Table 2: Barriers to care for women, by selected characteristics | ||||||||||||

| All | Insurance Type | Race/Ethnicity | Age Group | |||||||||

| Share of women reporting they delayed or went without care in past 12 months due to: | Private | Medicaid | Uninsured | White | Black | Latina | 18-25 | 26-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | |

| Didn’t have a regular doctor or provider | 12% | 8% | 18%* | 26%* | 11% | 10% | 16%* | 20%* | 16%* | 10% | 11%* | 6% |

| Had difficulty finding a provider that would accept her insurance plan | 12% | 8% | 29%* | _ | 11% | 10% | 13% | 18%* | 16%* | 8% | 11% | 9% |

| NOTES: Among women ages 18-64. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from Private, White, Ages 55-64, p<.05. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. |

||||||||||||

Site of Care

Most women seek care at doctors’ offices, but clinics are important sites of care for underserved communities, particularly for women of color and those without insurance.

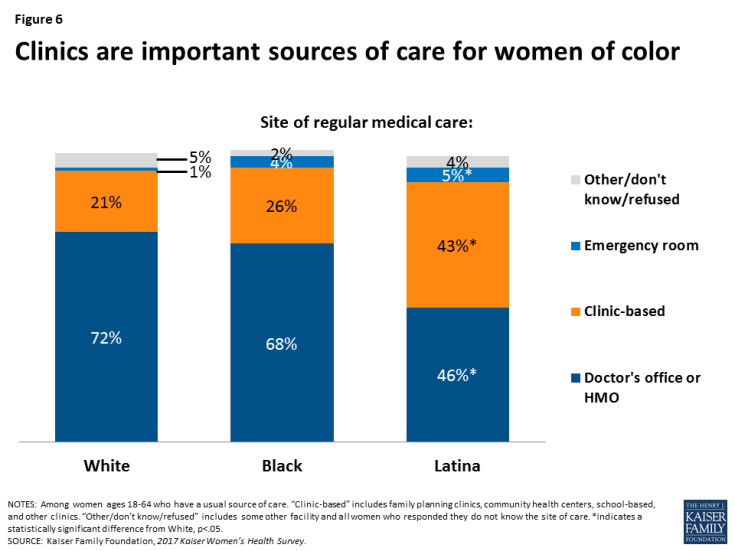

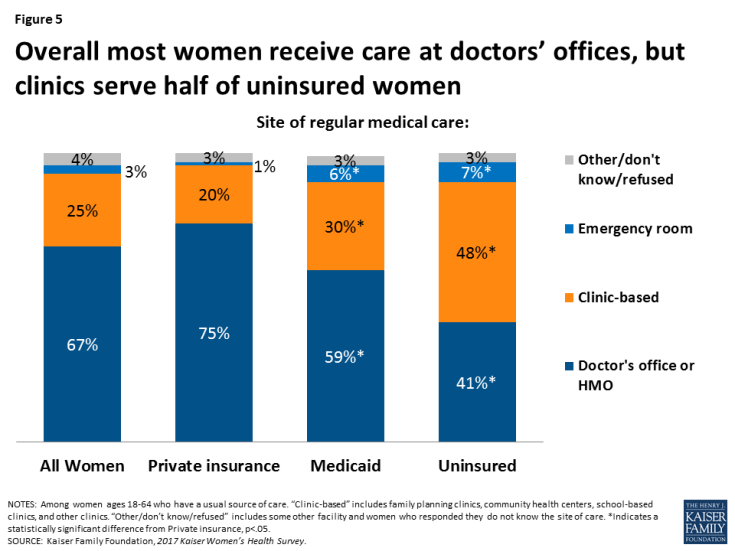

Two-thirds (67%) of women ages 18-64 with a usual source of care state they obtain their care at a doctor’s office or HMO (Figure 5). Another quarter obtain care at a clinic, such as a community health center. A small share (3%) cite the emergency room as their site of care. The pattern is similar among women with Medicaid, albeit a slightly lower share going to doctors’ offices (59%) and higher share going to clinics (30%). For uninsured women, the pattern is notably different, with almost half (48%) seeking care at a clinic. Women of color report also doctors’ offices as their leading site of care (Figure 6), but a considerably higher share of Latina women (43%) rely on clinics compared to White women (21%).

Figure 5: Overall most women receive care at doctors’ offices, but clinics serve half of uninsured women

There is a lot of discussion about how to reduce the inappropriate use of the emergency room for primary care services. While this is more common among women with Medicaid (6%) and those who are uninsured (7%), it still reflects a very small fraction of the population.

General Check-ups and Provider-Patient Counseling

Provider visits can give women an opportunity to talk with clinicians about a broad range of issues, including preventing illness, the role of lifestyle factors, and management of chronic illnesses. Under the ACA, new plans must cover at least one annual “well woman visit,” which the IOM Committee on Clinical Preventive Services for Women recommended could specifically cover a range of topics, such as assessment of diet and physical activity, preconception care, prenatal care, and screening for STIs.

The majority of women have had a recent checkup or well woman visit.

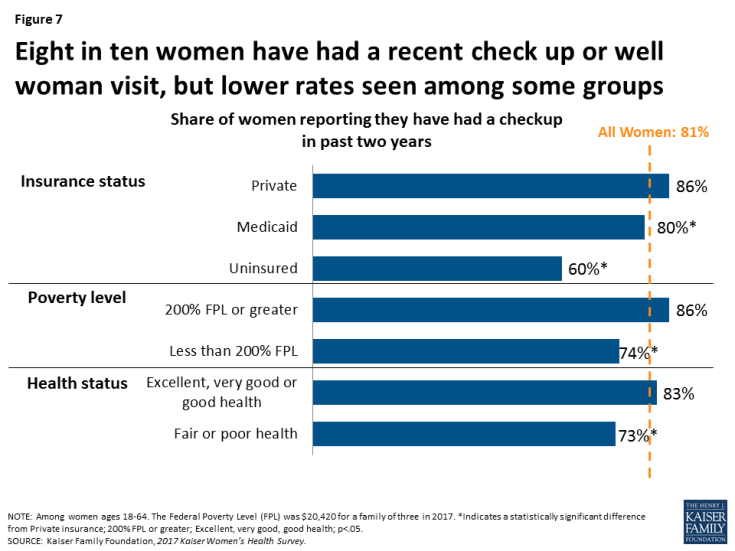

Eight in ten (81%) women have had a well-woman visit in the past two years (Figure 7), remaining constant from 2013 (82%). However, uninsured women (60%), women with incomes less than 200% FPL (74%), and women in poorer health (73%), are less likely to have had a recent checkup. Rates are similar among racial groups, although Black women (91%) report they have had a recent well woman visit at a higher rate than White (81%) or Latina (78%) women do.

Figure 7: Eight in ten women have had a recent check up or well woman visit, but lower rates seen among some groups

Most women reported that they went to an internist or family practitioner (43%) or an Ob-gyn (40%) for their well woman visit. There are differences by age group. Among women ages 18-44, almost half (47%) reported seeing an Ob-gyn and 37% saw an internist or family practitioner for their well woman visit. Among women ages 45 to 64, 50% reported going to an internist or family practitioner and 31% to an Ob-gyn. About one in ten women (12%) report that they saw a nurse practitioner or physician assistant for their well woman visit, with no significant differences by age group.

Rates of counseling on health behaviors are highest for diet, exercise, and nutrition.

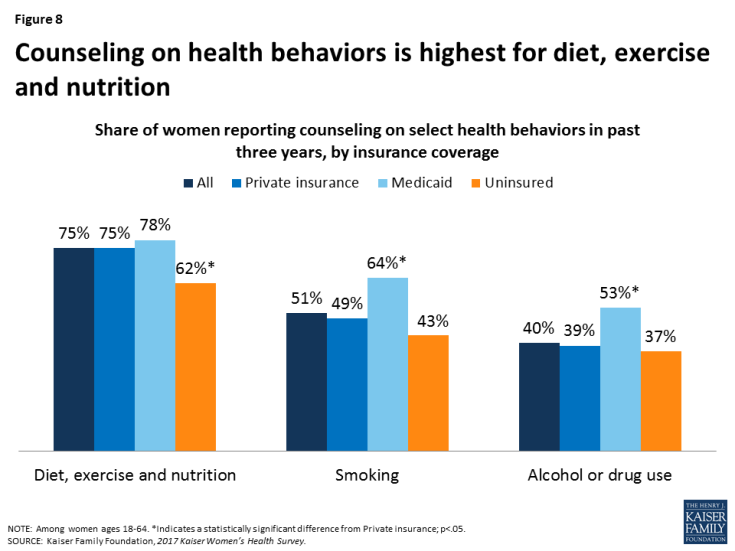

Counseling on health-related behaviors such as diet, smoking, and alcohol use can be an important component of women’s primary care. Consistent with other national trends, the highest rate of preventive counseling addresses diet and nutrition, which 75% of women have discussed with a provider in the past three years (Figure 8). Only half (51%) of women report having discussed smoking and four in ten (40%) have discussed alcohol or drug use with a provider in the past three years. Across the board, women covered by Medicaid report the highest rates of counseling. In addition, younger women and those in poorer health have higher counseling rates compared to their counterparts (Table 3).

| Table 3: Counseling rates on select health behaviors, by age group and health status | |||||||||

| All Women | Age Group | Health Status | Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| 18-44 | 45-64 | Fair or poor | Excellent to good | White | Black | Latina | |||

| Diet, exercise, and nutrition | 75% | 75% | 74% | 80%* | 73% | 73% | 82% | 75% | |

| Smoking | 51% | 54% | 47%* | 60%* | 49% | 50% | 57% | 51% | |

| Alcohol or drug use | 40% | 46% | 34%* | 44% | 40% | 37% | 45% | 46%* | |

| NOTES: Among women ages 18-64. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from 18-44, Excellent to good, White; p<.05. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. |

|||||||||

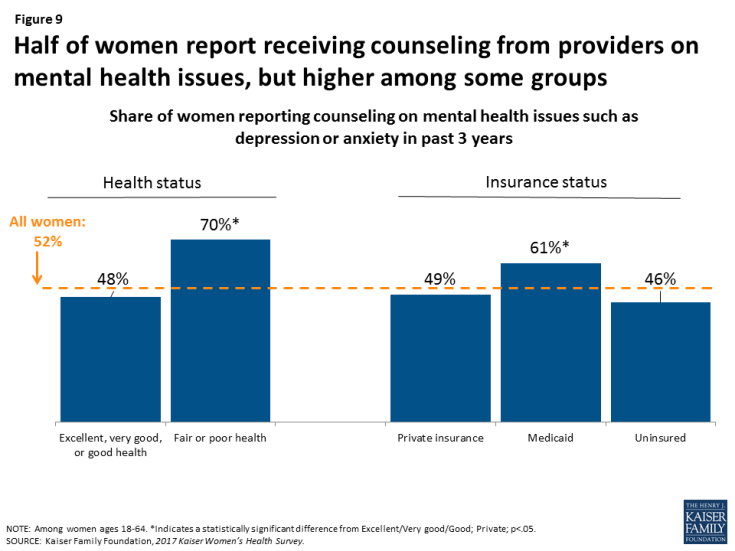

Half of women have talked recently with a provider about mental health issues, representing an increase since 2013.

Most plans must adhere to the Mental Health Parity Act, which requires that plans cover mental health treatment and treatment for other medical conditions equally. Depression and anxiety affect many women in particular over their lifetimes, and the USPSTF recommends depression screening, but there is not a recommendation for frequency. Half (52%) of women report having discussed mental health issues, such as anxiety or depression, in the past three years, up from 41% in 2013 (Figure 9). In 2017, about half of White (53%), Black (52%), and Latina (49%) women report they discussed mental health issues with a provider in the prior three years, up from 42% of White and Black women and 39% of Latina women in 2013. As with other counseling topics, the rate is higher among women who are sicker or covered by Medicaid. There were no significant differences by age.

Figure 9: Half of women report receiving counseling from providers on mental health issues, but higher among some groups

There has been an increase in patient counseling over the past several years.

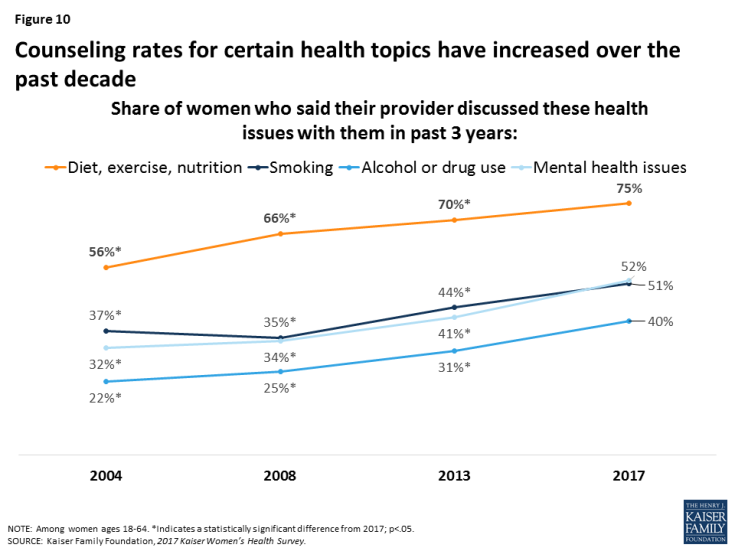

The share of women who report they have spoken with a provider about various health issues has risen over the past decade. In 2004, a third (32%) of women reported recently speaking with a provider about mental health issues, rising to more than half of women (52%) in 2017 (Figure 10). Provider counseling on smoking increased similarly from 37% in 2004 to 51% in 2017. Diet, exercise, and nutrition remains the most frequently discussed health issue, and while there has been a lot of attention about provider roles in curbing alcohol and drug misuse in light of the current opioid crisis, counseling on alcohol or drug use continues to be the least discussed issue.

Screening Tests

Use of preventive services can lead to early identification of conditions when they are more responsive to early interventions. This is especially true for some types of cancers and cardiovascular conditions. For example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends routine mammograms and pap tests to identify breast and cervical cancers respectively. The USPSTF also recommends regular screenings for colon cancer for women ages 50 and older. All of these services are covered by most private plans under the ACA’s preventive services coverage requirements and by most state Medicaid programs.

Rates of preventive screening tests are higher among women with insurance.

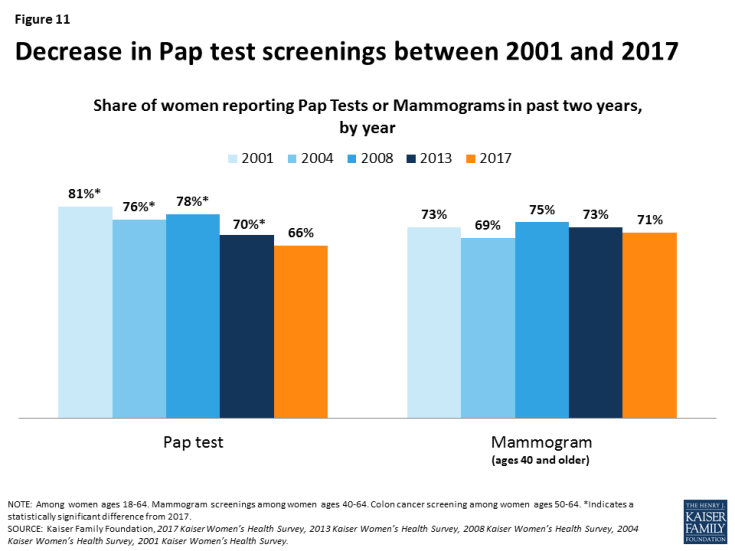

Most women have had cancer screenings in the past two years, including mammograms (71%) and Pap tests (66%), with variation by age group. Rates of Pap tests have been decreasing since 2001, likely due to changes in the recommendations and guidelines for cervical cancer screening, which reduced the frequency and narrowed the age group for testing compared to earlier guidelines (Figure 11). Rates of screening for colon cancer remain lower, with four in ten (41%) women ages 50 or older reporting a recent colorectal screening.

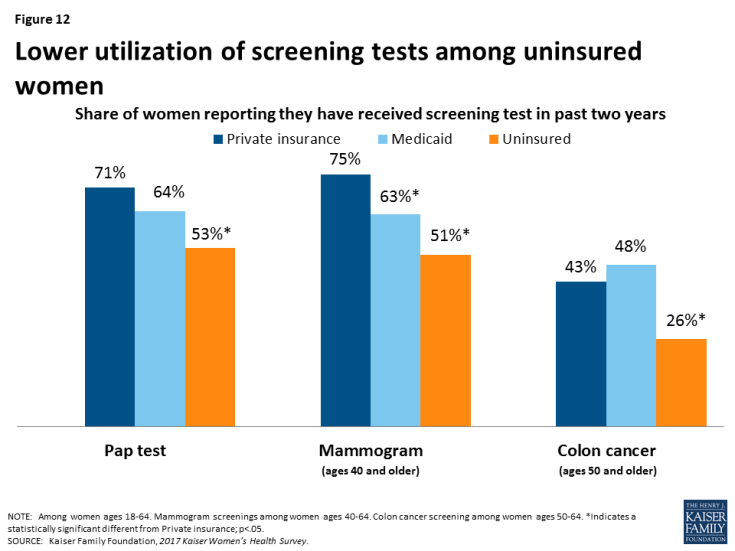

Uninsured women have consistently lower use of all screening tests (Figure 12). While 75% of women, age 40 and older, with private insurance and 63% of women with Medicaid have had a mammogram in the past two years, only 51% of uninsured women age 40 and older did. Just over half of uninsured women (53%) have had a Pap test in the past two years, compared to 71% of women with private insurance and 64% of women covered by Medicaid. Among women age 50 and older, rates of colon cancer screenings are highest among women covered by Medicaid (48%) and women with private insurance (43%), compared to a quarter (26%) of uninsured women.

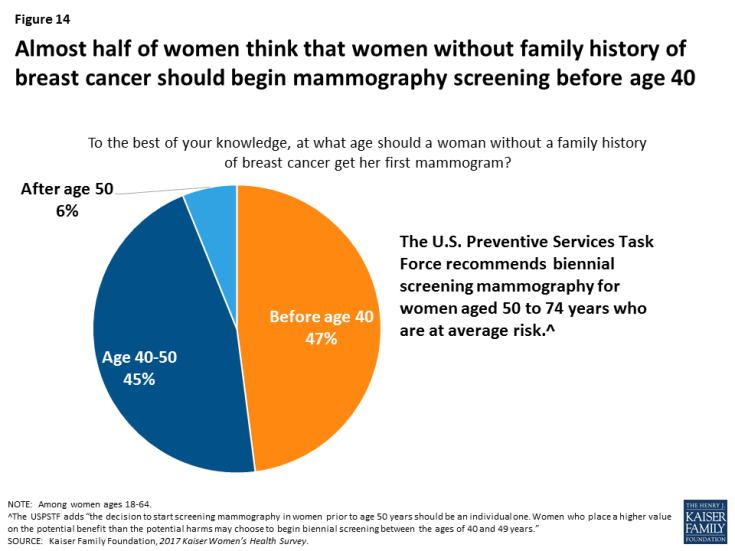

Many women think that women should begin screening tests for breast and cervical cancers at an earlier age than recommended by national groups.

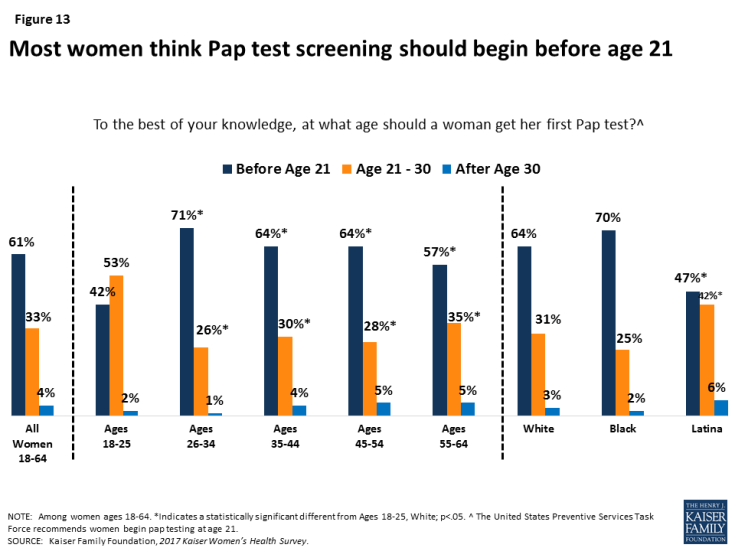

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends cervical cancer screenings for women age 21-65 by Pap smear every three years for women with normal screenings (Table 4). However, most women (61%) think that a woman should get her first pap test before the age of 21 (Figure 13). Young women ages 18-25 as well as Latinas are more likely to state that screening should begin between 21 and 30 years old. Some of the generational difference may be because recommendations for Pap screening have changed in the past decade, and older women may still recall the older guideline, which did recommend that women begin pap screening at a younger age.

The USPSTF recommends breast cancer screenings for women without a family history for women ages 50 and older every two years. However, guidelines surrounding mammography have been debated fiercely in recent years. Professional organizations vary in their recommendations, and some still recommend screening beginning at age 40 or 45. Regardless, almost half (47%) of women say that a woman without a family history of breast cancer should get her first mammogram before the age of 40 (Figure 14). This is more common among young women 18-25 (64%) compared to women ages 26-34 (48%), 35-44 (34%), 45-54 (43%), and 55-64 (51%). This is also more common among low-income women (54%) than among their higher income (43%) counterparts (data not shown).

Figure 14: Almost half of women think that women without family history of breast cancer should begin mammography screening before age 40

| Table 4: USPSTF national recommendations for preventive cancer screenings for average risk women | ||

| Screening Service | Population | Frequency |

| Breast cancer screening | Women ages 50-74* | Mammography every 2 years. |

| Colorectal cancer screening | Adults age 50 – 75 | Varies based on procedure. |

| Cervical cancer screening | Women age 21 – 65 | Pap smear every 3 years for women age 21 – 65 or combination of Pap smear and HPV test every 5 years for women age 30 to 65. |

| NOTES: *The USPSTF adds “the decision to start screening mammography in women prior to age 50 years should be an individual one. Women who place a higher value on the potential benefit than the potential harms may choose to begin biennial screening between the ages of 40 and 49 years.” | ||

Conclusion

Most women report having a place and provider where they seek care, and most have had a recent doctor’s visit. However, connections to the delivery system are more tenuous for low-income and uninsured women, who are less likely to report a recent visit or regular site of care. Private doctors’ offices continue to be the most common site of care for women. Nonetheless, clinics play a critical role for many, especially women of color, women insured by Medicaid, and the uninsured. This is particularly important in light of recent public policy debates about whether public funding should be eliminated for specialized family planning clinics, such as Planned Parenthood that also offer abortion services.

The ACA prioritized prevention by requiring insurance plans to cover without any out of pocket costs routine checkups and several screening tests for women. Most women report they have had a well woman visit in the past two years, but similar to other measures, rates are lower among low-income and uninsured women. While the share of women that received provider counseling on various health issues has increased since 2013, just about 40-50% of women report they have talked to a provider about mental health, smoking, and alcohol or drug use in recent years. There is also very little awareness about national recommendations for initiation of routine screenings such as the Pap test and mammogram.

This brief was prepared by Usha Ranji, Caroline Rosenzweig, and Alina Salganicoff of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The authors would like to thank Anthony Damico, an independent consultant, for his assistance with survey analysis.