Telemedicine and Pregnancy Care

|

Key Takeaways

|

|

Introduction

While global trends show maternal morbidity and mortality improving, the U.S. stands out as one of the only countries where maternal morbidity and mortality have actually worsened over the last few decades. The U.S. has lagged behind other high-income countries, often attributed to poor access to prenatal care, high rates of chronic disease, and the highest rate of skipping necessary health care due to cost barriers. Poorer obstetrical outcomes are particularly pronounced among Black women and American Indian/Alaska Native women, as well as women living in rural areas. Ten million women in the U.S. live in rural counties where obstetricians are scarce and pregnant people often must travel significant distances to access care due to hospital closures. A recent study found that rural residents have a 9% greater likelihood of severe maternal morbidity/mortality than their urban counterparts because of factors including workforce shortages, transportation barriers, the opioid epidemic and limited access to specialty care.

Telemedicine, or telehealth, is one proposed method to address these disparities, defined broadly as the provision of health care services by health care professionals, using technology to exchange information in the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease. In fact, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has endorsed telemedicine to improve maternal morbidity and mortality, encourages OBGYNs to adopt these technologies. ACOG writes that telehealth opportunities “enhance, not replace, the current standard of care.” This brief outlines how telemedicine is currently used in obstetrical care, how these services are financed and regulated, and reviews federal efforts to expand the use of telemedicine, particularly to address maternal health disparities.

Telemedicine in Obstetrical Care

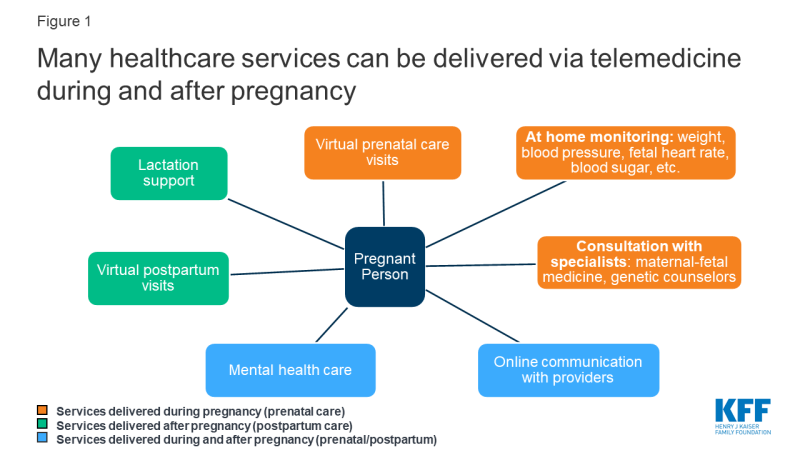

A broad range of pregnancy-related services can be offered via telemedicine. Telemedicine has been used for innovative approaches to prenatal/postpartum care, at-home monitoring for conditions like diabetes and hypertension, and for phone/video consultation with specialists (i.e. high-risk obstetricians, lactation consultants, mental healthcare providers) (Figure 1).

Utilization for pregnancy-related care is very low. Using a sample of outpatient medical claims of reproductive age women enrolled in large employer plans, KFF analyzed telemedicine utilization within the following domains of pregnancy-related care: supervision of normal and high-risk pregnancies, mental health disorders associated with pregnancy and lactation services.1 Of all de-duplicated claims analyzed within pregnancy-related care, just 0.1% were delivered via telemedicine. The majority of telehealth encounters took place over the phone, while a minority took place online. Examples of the claims delivered via telemedicine included visits for lactation complications, postpartum mood disturbances, postpartum follow up and routine prenatal care. These data do not include uninsured patients or patients with public insurance, and also may not capture services delivered using bundled payment plans for pregnancy care.

Prenatal Care: Reducing the Need to Travel

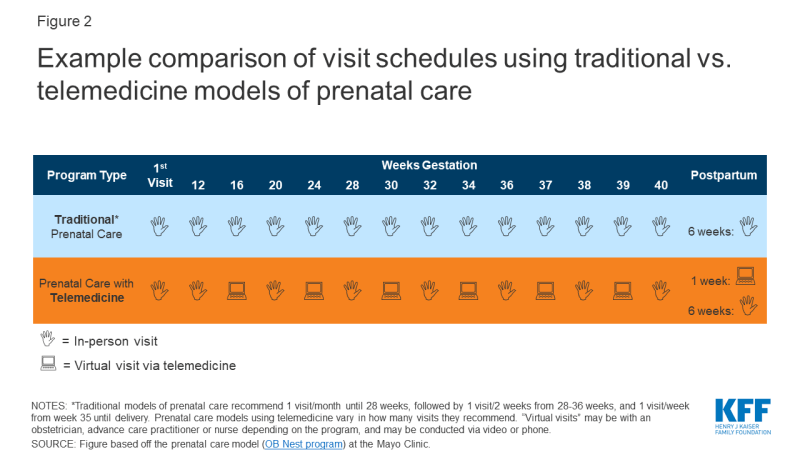

Traditional prenatal care models recommend upwards of 14 in-person visits2 throughout pregnancy. This requires significant travel time and time away from work or family responsibilities. But only some prenatal visits truly require in-person care, like those for ultrasounds, lab testing and vaccinations. Many visits are to provide patient education, answer questions and monitor maternal and fetal vitals, measurements that could be taken at home if given the supplies. Research suggests that fewer prenatal visits are safe for low-risk pregnancies. In response, some medical centers have started to use telemedicine “virtual visits” via videoconference or phone to replace some in-person visits. Patients are given instructions and supplies to monitor blood pressure, weight, fetal heart rate and fundal height at home. These programs allow for patients to maintain continuity of care with their OB providers, while partaking in parts of their care from home or a convenient location. This can be especially helpful for patients who need to travel long distances to care, or have barriers to taking time off from work or family responsibilities. Figure 2 provides an example of how a virtual prenatal care schedule may compare to traditional care.

Figure 2: Example comparison of visit schedules using traditional vs. telemedicine models of prenatal care

Currently, the vast majority of prenatal care in the U.S. happens in-person, but there are some medical centers who have begun to implement telemedicine in their prenatal care (Table 1). Research shows comparable pregnancy outcomes between telemedicine and traditional care groups, with the caveat that in one program, patients using virtual visits had a higher incidence of preeclampsia than in traditional care. Telemedicine was also saved patients time and potentially lowered visit-related costs to the patient.

| Table 1: Examples of Prenatal Care Programs Using Telemedicine | ||

| Provider (State) | Description | Program Evaluation |

| Mayo Clinic (NY) |

|

|

| MultiCare (WA) |

|

|

| University of Utah (UT) |

|

|

| George Washington University (DC) |

|

|

At-Home Monitoring

High risk pregnancies can also benefit from telemedicine, particularly through use of at-home monitoring for high blood pressure and diabetes, which is then transmitted to their providers. Studies show patients value at-home monitoring, as it allows for active participation in their care and promotes self-efficacy. For patients with diabetes, at-home monitoring of blood sugar may allow for fewer visits to diabetes specialists, and improved health-related quality of life. A review of 7 studies found the use of telemedicine for blood sugar monitoring was as effective as standard care in achieving glucose control in pregnancy. Multiple studies of women with gestational diabetes showed similar pregnancy outcomes between telemedicine and traditional care.

Hypertension management normally requires frequent in-person checks.3 With telemedicine, patients may monitor their blood pressure at home, with results sent to their providers who can decide if they need in-person evaluation. Two studies of women with hypertension in pregnancy (both prenatal and postpartum) found at-home blood pressure measurement was feasible in detecting spikes in blood pressure and acceptable to most patients. More research is warranted to compare blood pressure control and pregnancy outcomes between telemedicine and traditional in-person models.

Consultation with Specialists

Many rural areas lack access to specialists, in particular maternal-fetal medicine doctors (MFMs) (high risk obstetricians). In fact, in 2010, there were only 1,355 MFMs across the entire U.S., with nearly all in urban centers. With telemedicine, patients and their local prenatal care providers can videoconference with a MFM or other specialist rather than traveling to see them in-person. Specialists can not only evaluate patients remotely and recommend management plans using this technology, but can even review ultrasound imaging as a remote technician conducts the exam. Telemedicine can also connect patients to genetic counselors, fetal cardiologists, and diabetes educators (Table 2).

Evaluations of these programs show that remote consults are generally feasible, acceptable to patients, and can save patients time and money on travel. Telemedicine may also increase access to specialty care for patients who may otherwise forgo this care due to lack of availability in their communities. Having specialists accessible via telemedicine may also encourage local providers to maintain care of their high-risk patients and safely facilitate more deliveries in nearby hospitals.

| Table 2: Telemedicine Specialist Consultations in High-Risk Pregnancies | ||

| Provider (State) | Description | Program Evaluation |

| University of Pittsburgh Medical Center UPMC (PA) |

|

|

| University of Arkansas Medical Sciences (UAMS) “ANGELS” program (AR) |

|

|

| STORC: Solutions to Obstetrics in Rural Communities (TN, GA, NC, AL) |

|

|

| Children’s Hospital Colorado (CO) |

|

|

| NOTES: MFM = Maternal Fetal Medicine doctor. Among many others, the following medical centers have also implemented telemedicine for MFM consultations: University of Virginia, Medical University of South Carolina, University of North Carolina Medical Center, University of Iowa, Washington University in St. Louis, University of New Mexico, Women’s Telehealth, West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, The Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. | ||

Communication with Providers

Telemedicine can also facilitate direct communication with providers, via online platforms or web-based apps. For example, participants in the Mayo Clinic telemedicine program can message nurses and peers through an online platform. Similarly, on Due Date Plus, a free mobile app created by Wyoming Medicaid patients can directly access nursing support. This app also includes pregnancy education, appointment reminders and information about Medicaid benefits and providers. A study of 85 app users compared to over 5000 non-users found app use was associated with a lower risk of delivering a low birth weight infant and a higher likelihood of completing prenatal care appointments.

Postpartum Visits

Postpartum care is key to addressing not only the physical well-being of the patient after delivery, but also their emotional and social well-being, breastfeeding concerns, contraceptive needs, birth spacing and any ongoing chronic disease management. However, the postpartum period, is often overlooked. Traditionally, patients wait 6 weeks before their postpartum visit, even though problems may arise before then. ACOG now recommends contact with the patient within 3 weeks of delivery, but up to 40% of women do not attend any postpartum visit. Use of telemedicine in postpartum care could help address this, through use of app-based support, enhanced phone or text communication with providers, and at-home blood pressure monitoring.

Most programs using telemedicine for prenatal care have a postpartum telemedicine visit built into the program. For example, patients enrolled in MultiCare’s program see a nurse practitioner via a virtual visit at 1 week postpartum, and their doctor in person at 6 weeks postpartum. Patients in the Mayo Clinic program have a phone call with a nurse at 1 week postpartum, before seeing their doctor in clinic at 6-8 weeks. Patients in these telemedicine programs already have monitoring equipment at home, which means they can monitor their blood pressure postpartum, important in delayed preeclampsia.

Lactation Support

Several telemedicine platforms allow individuals with breastfeeding difficulties to access lactation consultants from their home or a nearby telemedicine “hub” (Table 3). These “telelactation” services allow clients to message consultants (typically International Board Certified Lactation Consultants), and participate in virtual visits by phone or videoconference. This model can offer benefits over in-person care, including increased convenience, eliminating travel costs and allowing for more timely delivery of services, often within minutes or hours of when the need arises. Virtual visits can be challenging, however, especially for those with inadequate internet access and limited computer literacy.

| Table 3: Examples of Telelactation Services | ||

| Platform | Services Available | Cost & Coverage |

| Amwell |

|

|

| Maven |

|

|

| Pacify |

|

|

| Lactation Link |

|

|

| Texas WIC |

|

|

| LiveHealth Online |

|

|

| Nest |

|

|

| NOTES: IBCLC = International Board Certified Lactation Consultants. WIC = Women, infants and children program. SOURCE: Uscher-Pines et al. The emergence and promise of telelactation. 2017. |

||

A recent review of 23 articles from 2000 to 2018 evaluated lactation support delivered via phone calls, videoconference, text messaging, mobile apps and interactive websites. While evidence in the field is limited due to small sample sizes, researchers found telelactation services were feasible and associated with user satisfaction. In a study of 10 mom-baby pairs who videoconferenced weekly with a lactation consultant, 100% of women were comfortable talking about breastfeeding via videoconference and found the service helpful. Sound quality and connectivity issues were cited as barriers. Further, in a study of 724 women, those who received weekly telephone support from lactation consultants were significantly more likely to continue breastfeeding at 1 and 2 months postpartum as compared to those with standard care.

Obstetrics & Mental Health

Many individuals require mental health services while pregnant or postpartum. This could include help for mood disorders, including postpartum depression and anxiety, postpartum psychosis, trauma, and substance use disorders. Some medical centers have started to offer telemedicine mental health services alongside pregnancy care. The Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) offers behavioral health telemedicine visits for pregnant/postpartum patients living outside the Charleston area, and accepts most insurance plans. The University of Arkansas Medical Sciences will expand their Women’s Mental Health Program in the upcoming year, to include telemedicine services for pregnant patients. Yale University received a large federal grant to study the use of telemedicine for substance use disorders in pregnancy.

Patients can also access mental health clinicians through Amwell, an online platform offering video visits to diagnosis and treat postpartum depression. This service is accessed completely online, rather than in conjunction with an in-person health system. An initial psychiatry visit costs $199. Follow up visits cost $95; Amwell accepts many private insurance plans but does not accept public insurance at this time.

Research to support use of telemedicine for prenatal/postpartum mental health is limited. A systematic review (10 studies) showed cognitive behavioral therapy via telemedicine (phone, email, app/websites) overall resulted in improvements in maternal depression, although the quality of evidence varied. Preliminary data from another systematic review (4 studies) on telemedicine for postpartum mood disorders suggested improvement in symptoms at 3-12 months post-intervention. The crossover between reproductive health and psychiatry constitutes a growth opportunity in telemedicine, especially given that outside of pregnancy, tele-mental health is reimbursed more often than other specialties.

Cost Considerations

It remains unclear how many of the aforementioned telemedicine services in obstetrics are financed and how cost compares to in-person care. For medical centers experimenting with video visits for prenatal care, these virtual visits may be able to be included as part of a bundled care model, as is the case for the Mayo Clinic OB program. For practices using fee for service models, it is less clear how the cost of using telemedicine would compare to an in-person prenatal care visit. An important consideration when using telemedicine to consult with specialists is for referring providers to ensure consulting providers are in-network for their patients.

For at-home monitoring in pregnancy, purchasing of the monitoring devices poses a challenge to implementing this care model. While some medical practices provide devices free of charge to patients for home monitoring, others require the patients purchase equipment out of pocket, which is prohibitive for low-income patients. This may involve purchasing a scale, blood pressure cuff, fetal doppler monitor and glucometer, not to mention having access to a smartphone or computer with reliable internet.

Coverage Regulations

While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires private insurance plans4 and Medicaid expansion programs5 to cover maternity care without cost sharing to the patient, including prenatal screenings and lactation consultations, there is no federal requirement to reimburse for telemedicine, or telemedicine in pregnancy. Each state regulates and reimburses for telemedicine differently, and regulations differ between public and private insurance plans. In a recent committee opinion, ACOG encouraged insurance companies to provide clear guidelines regarding telehealth coverage and reimbursement, as variation in payment models poses a barrier to telehealth implementation.

Medicaid

In 2018, Medicaid financed 42% of all births in the U.S., including 65% of births for Black women, 59% of births for Hispanic women, and 77% of births for women under 20 years old. Under federal law, Medicaid must cover pregnancy-related services and provide 60 days of postpartum coverage for women with incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty line (FDL), while many state Medicaid programs extend eligibility beyond this income level. While maternity care services may be covered in-person, few states require coverage if delivered via telemedicine.

Only a handful of state Medicaid programs specifically address obstetrical care in their telemedicine reimbursement laws; some choose to explicitly cover services like video visits with an OBGYN or behavioral health provider in pregnancy, real-time OB ultrasounds via telemedicine, and at home monitoring during pregnancy for certain conditions (Table 4). Meanwhile, North Dakota’s Medicaid program specifically excludes coverage of live video services for use in case management for high-risk pregnancies. Only 19 state Medicaid programs reimburse for telemedicine services delivered to the patient in their home, therefore limiting the reimbursement of tele-lactation services and at-home monitoring in pregnancy. Most states do not specifically mention pregnancy-related care in their Medicaid reimbursement laws and policies, meaning these technologies may be out of reach for low-income women.

| Table 4: Examples of State Medicaid Programs that Require Coverage of Some Telemedicine Services in Pregnancy | ||

| State | Required to cover | Eligible conditions include: |

| AZ | Live video | Services within obstetrics/gynecology and behavioral health |

| IL | At-home uterine monitoring | Pregnancies after 24 weeks complicated by multiple gestations or preterm labor |

| At-home blood pressure monitoring | For pregnancies complicated by pregnancy-induced hypertension (does not cover patients with chronic hypertension) | |

| MA | Live video | Behavioral health services for pregnant/postpartum patients |

| MO | At-home monitoring | Pregnancy but only if other risk factors present like documented history of care access challenges, documented history of missed appointments, etc. |

| TX | At-home monitoring | Pregnancy, diabetes, hypertension |

| VA | Live video | Specialty procedures like obstetric ultrasound |

| At-home monitoring | Pregnant women who are injecting insulin | |

| NOTES: This is not an exhaustive list of telemedicine services covered during pregnancy under Medicaid. Rather, this list highlights only those states that specifically mention pregnancy-related conditions in their telemedicine laws. SOURCE: Center for Connected Health Policy. State Telehealth Laws & Reimbursement Policies. Fall 2019. |

||

Private Insurance

No states specifically require private insurance plans to cover pregnancy services in their telemedicine reimbursement laws. However, in approximately half of states, if telemedicine services are shown to be medically necessary and meet the same standards of care as in-person services, private insurance plans must cover telemedicine services if they would normally cover the service in-person, called “service parity.” Fewer states require “payment parity,” meaning telemedicine services are reimbursed at the same rate as equivalent in-person services. Before utilizing telemedicine services during pregnancy, patients would need to check with their insurance carrier for coverage information, as these services are not explicitly required to be covered. KFF’s brief on telemedicine in sexual and reproductive health goes into further detail on how states regulate telemedicine more generally, including licensing/malpractice concerns, online prescribing laws, and reimbursement/coverage of services.

Access and Policy

The majority of pregnant individuals do not have access to telemedicine services at this time. Only a handful of medical centers have adopted telemedicine into their prenatal care schedules. While more have incorporated telemedicine services for specialist consults, including MFMs, lactation consultants and psychiatric care, utilization is minimal. Aside from insurance considerations, barriers to initiating a telemedicine program include significant planning time and start-up costs, reliable broadband connections both at the site of the provider and the patient, HIPPA compliance, and integration into the electronic health record. This can be particularly challenging in low-resource and rural settings; however, efforts are in place by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to increase internet access for use in telehealth for these populations. Clinicians must also ensure they are licensed to practice in other states (if applicable), and their malpractice insurance covers telemedicine.

A few states have included telemedicine interventions in their plans for addressing maternal health care disparities. For example, the Montana Obstetric and Maternal Support program launching in 2020 received $10 million from the federal government to address maternal health disparities; the program will focus in part on expanding telehealth interventions, including connecting rural patients and clinicians to OBGYN specialists in urban communities. Similarly, Maine is one of 10 states to receive a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid funded grant to tackle opioid use disorder in pregnancy; part of their approach will include use of telehealth to increase provide capacity across the state. Other states have introduced legislation to expand telemedicine’s use. In 2019, New Jersey proposed bills to create telemedicine practice standards for midwives and genetic counselors. Texas proposed multiple telemedicine projects, including researching the costs/benefits of reimbursing prenatal and postpartum care, establishing a program to treat mood disorders in pregnancy and requiring hospitals to have obstetricians available by telemedicine or in-person at all times, but these efforts all failed to pass. At a federal level, several bills addressing maternal morbidity and mortality have included telemedicine interventions, all of which are currently referred to or in committee (Table 5).

| Table 5: Federal Maternal Health Legislation that Incorporate Telemedicine | ||

| Bill | Cosponsors | Telemedicine Interventions Proposed |

| Rural Maternal and Obstetric Modernization of Services Act (Rural MOMS) (S.2373 and H.R. 4243) | Bipartisan | Would expand telemedicine obstetric and postpartum services in rural areas |

| Maternal Health Quality Improvement Act of 2019 (H.R.4995) | Bipartisan | Would create telehealth network grant programs for rural areas |

| MOMMIES Act (S.1343) | Democrat | Would study the efficacy of using telemedicine in maternity care for Medicaid beneficiaries (including demographics of users, health outcomes, patient satisfaction and cost savings) |

| Healthy MOMMIES Act (H.R.2602) | Democrat | |

| NOTES: As of January 2020, all bills have been either referred to or are being discussed in committee. | ||

Looking forward

Despite low utilization at this time, there are a myriad of ways telemedicine can be integrated into prenatal and postpartum care. These technologies could be particularly useful in addressing rural-urban health disparities in maternal care, by improving access to specialists like MFMs and mental health providers, enabling at-home monitoring of hypertension and diabetes, and reducing transportation barriers. While these interventions hold great promise in improving access and maternal/infant health disparities, major implementation challenges persist. Nearly half of births in the U.S. are financed by Medicaid, however state Medicaid programs rarely require coverage for telemedicine services in pregnancy, limiting utilization in a significant portion of the pregnant population. In addition, limited internet access among low-income and rural populations and high startup investments for health systems pose challenges to telemedicine’s implementation. Federal and state efforts to support use of telemedicine services for maternity care exist, but expansion of these services will likely depend on decisions regarding insurance coverage and reimbursement. Broadening the reach of telemedicine to more underserved communities may help improve maternal and infant health outcomes.