Private Insurance Coverage of Contraception

Insurance coverage of contraceptive services has been the focus of policy attention by state and federal policy makers as well as in the courts over the past two decades. In 2012, all new private plans were required to cover, without cost-sharing, the full range of contraceptives and services approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as prescribed for women.1 For the first time, federal standards created a minimum set of benefits for most health plans regulated by the federal government (self-insured plans, federal employee plans) and states (individual, small and large group plans), including contraceptive coverage for women with no cost-sharing. This new requirement, however, has been at the center of a heated policy debate that culminated in the Supreme Court ruling on the religious rights of employers that object to contraception. At this time, the issue has not yet been resolved as additional cases are working their way through the courts, and may end up, yet again, at the Supreme Court. This issue brief explains the rules for private insurance coverage of contraceptives at the federal and state level and discusses key issues regarding the provision and coverage of contraception by private insurance plans.

Background

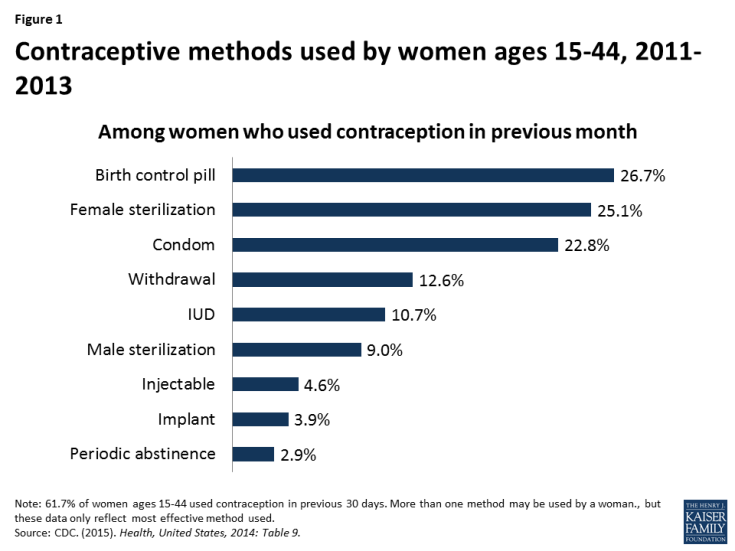

Access to contraception is a key element in shaping women’s health and well-being. Contraception is most notably used for family planning, but also to control symptoms associated with menstruation, endometriosis, and acne.2 Nearly all women (99%) have used contraceptives at some point in their lives and 62% of women are currently using at least one method.3 Of the more than 60 million women in their childbearing years (ages 15 to 44), 7 in 10 are sexually active and do not want to become pregnant.4 The most common form of contraception among women currently using contraception is the pill (26.7%) followed by female sterilization (25.1%) and male condoms (22.8%) (Figure 1).5 Use of long acting reversible contraception (LARCs) has been increasing over recent decades with the introduction of new intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants.6 Efficacy of various methods ranges from greater than 99% effective with IUDs, to 91% with oral contraceptive pills, and 82% with condoms.7 According to the CDC, 6.9% of women of reproductive age are sexually active but are not using contraception, placing them at increased risk for unintended pregnancy.8

Unintended pregnancies account for almost half of all pregnancies in the US.9 Women who use contraception incorrectly, experience gaps in contraceptive use, or do not use contraception are at particular risk for experiencing an unintended pregnancy, but no method is 100% effective. Approximately one quarter (23%) of women using contraception had a period of at least 1 month in the prior year when they were not using a contraceptive method.10 Insurance coverage of contraception has been shown to increase utilization of contraception, increase use of more effective methods, and decrease out-of-pocket costs for women.

The ACA’s Contraceptive Coverage Requirement

The ACA is the first law to set coverage requirement for health insurance across all markets – individual, small group, large group and self-insured plans. Individual, small and large group plans are regulated by the state, whereas self-insured plans are regulated by the federal government under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

Before the ACA, coverage for prescription contraceptives was generally widespread in the private and public sectors, but not universal. Unless a state had a contraceptive coverage mandate, insurers and employers could choose whether or not to provide coverage for contraception. In 2000, a ruling by the Employment Equal Opportunity Commission found that employers that covered preventive prescription drugs and services, but did not cover prescription contraceptives were in violation of the Civil Rights Act.11 Currently, 28 states require insurance plans to cover contraceptives, with a wide range of coverage and cost-sharing requirements, and exemptions among these mandates.12 State laws, however, fell short of universal coverage as they only applied to state regulated plans, but not self-funded plans where 61% of covered workers are insured.13 In addition, they did not place contraceptives in a special class that was protected from cost-sharing.

More than half of women in the United States are insured through an employer-sponsored plan, either as the primary beneficiary or as a spouse or dependent. The 2010 Kaiser/HRET survey of employers reported that 85% of large firms covered prescription contraceptives in their largest health plans14, although they may have charged cost-sharing, the amount of which can vary greatly by employer and type of plan. Only a small share of women has historically purchased insurance directly from an insurance company on the individual market, but this share is growing as previously uninsured women can now purchase coverage through ACA Marketplaces.

The ACA made contraceptive coverage a national policy, by requiring most private health insurance plans to provide coverage for a broad range of preventive services including FDA-approved prescription contraceptives15 and services for women without cost-sharing. Since the implementation of the ACA’s contraceptive coverage provision, fewer women are paying out of pocket for contraceptives.16 For example, the share of reproductive age women experiencing out-of-pocket spending on oral contraceptive pills declined from 20.9% in 2012 to 3.6% in 2014. This decline accounts for nearly two-thirds (63%) of the drop in out-of-pocket spending on retail drugs during this time period.

While most health plans are now required to provide contraceptive methods and counseling to women with reproductive capacity with no out-of-pocket costs, there are certain conditions that must be met. Women must be enrolled in a non-grandfathered plan17 and they must get services from an in-network provider. 18

In addition, the federal regulations implementing the preventive services coverage requirement explicitly permit plans and issuers to use reasonable medical management to control cost and promote efficient delivery of care.19 This applies to coverage of all preventive services, not just contraceptive care, but contraceptive services in particular had been documented as being unevenly covered by some plans because of how medical management was being interpreted by insurers.20 Examples of medical management tactics include, but are not limited to, categorizing brand and generic drugs and devices in tiers based on either cost, type and or mode of delivery; steering consumers to generic equivalent drug options; requiring provider authorization to acquire a preferred brand drug; requiring a consumer to first try a lower tier formulary drug or therapy to treat a medical condition before they will pay for an alternative drug or therapy for that condition (step therapy); and limiting quantity and or supply.

In response to reports about gaps in contraceptive coverage attributable to medical management policies,21 the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued new guidance in May 2015 which clarifies that at least one form of all 18 FDA-approved methods of birth control must be covered without cost-sharing. If a provider recommends a specific option or product, plans must cover it without cost-sharing as well. Insurers may use reasonable medical management, however, to limit coverage to generic drugs when a generic version exists, and can impose cost-sharing for equivalent branded drugs. Plans are required to have a “waiver” process for women who have a medical need for contraceptives otherwise subject to cost-sharing or not covered.22

Exemptions and Accommodations

As mentioned above, women enrolled in “grandfathered” plans may not be covered for the full range of contraceptives without cost-sharing. In order to be classified as “grandfathered,” plans must have been in existence prior to March 23, 2010, and cannot make significant changes to their coverage (for example, increasing patient cost-sharing, cutting benefits, or reducing employer contributions). In 2014, 26% of workers covered in employer sponsored plans were still in grandfathered plans,23 and it is expected that over time almost all plans will lose their grandfathered status.

Certain religious employers have a religious objection to some or all contraceptive methods and may be “exempt” from the ACA contraceptive coverage mandate. Specifically “religious employers”, primarily churches and other institutions of worship are exempt. Exempt employers do not have to include contraceptive coverage for their workers and their dependents in their health plan.

There is also an “accommodation” available to nonprofit religiously-affiliated organizations and closely held24 for-profit corporations that object to contraceptive coverage on religious grounds25 Under the accommodation, an eligible employer does not have to contract, arrange, pay or refer their employees for contraceptive coverage. The health carrier used by the nonprofit employer or closely held for-profit employer must notify the policyholders, and provide separate coverage of contraceptives, at no cost, to the policyholders. Unlike an exemption, female employees and the female dependents covered by the plans of a nonprofit or closely held for-profit employer choosing an accommodation are entitled to the full contraceptive coverage from their insurance carrier.

Looking Forward

Today, millions of women now have coverage for the full range of contraceptive methods without cost-sharing; however, some women will continue to experience gaps in coverage. Federal and state regulators have an important role to play in ensuring the federal standards are applied accurately and fairly, meaning all women can access contraceptive services. In May 2016, the Supreme Court remanded Zubik v. Burwell, sending 7 cases brought by religious nonprofits objecting to the contraceptive coverage accommodation back to the respective Courts of Appeal. The Court instructed the parties to work together to “arrive at an approach going forward that accommodates petitioners’ religious exercise while at the same time ensuring that women covered by petitioners’ health plans “receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage.”26 It is not clear whether the Trump Administration will maintain the contraceptive coverage policy.

Awareness of the Federal Standard Among Women and Providers

A recent HHS study estimates that 55 million women have private insurance coverage that includes no-cost coverage for contraceptive services and supplies.27 While the number of individuals who have gained coverage for no-cost preventive services is large, public awareness of the preventive services requirement is relatively low. In March 2014, three and half years after the rule took effect, less than half the population (43%) reported they were aware that the ACA eliminated out-of-pocket expenses for preventive services.28 A Kaiser Family Foundation study on plan coverage of contraceptives identified that some providers may not know how to correctly code all visits related to contraceptive services as a preventive service so the patient is not billed for the service.29 For the contraceptive coverage requirement to reach all women enrolled in private plans, additional public and provider education is needed.

Role of States in Expanding Coverage

States have historically regulated insurance and many have mandated minimum benefits for decades. Contraceptive coverage is no exception. Since the passage of the ACA, some states have looked to strengthening and expanding the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. For example, in 2014 California passed the Contraceptive Coverage Equity Act of 2014 which requires plans to cover prescribed FDA-approved contraceptives for women without cost-sharing. The law specifies that a plan does not have to cover more than one therapeutic equivalent of a contraceptive drug, device, or product, as long as at least one is covered without cost-sharing. Contraceptives with the same chemical formulation and delivery mechanism are therapeutically equivalent. Starting in January 2016, plans in California will be required to cover the cooper IUD (Paragard) and all three hormonal IUDs (Mirena, Skyla and Liletta), because none of the IUDs are therapeutically equivalent. The ACA requires plans to cover Pargard, and only one hormonal IUD.

In 2015, Oregon passed a law that requires insurers to pay for a 3 month supply of contraceptives when first prescribed, followed by a 12 month supply of contraceptives regardless of whether the woman was insured by the same plan at the time of the first dispensing.30 This law applies to oral contraceptive pills, the patch and the vaginal ring. In June 2015, the D.C. mayor signed a similar measure which would require health insurers that offer coverage of prescription birth control pills to cover a 12-month supply dispensed at one time. Congress has 30 days to review this bill.

Confidentiality and Consent for Minors and Young Adults

Prior to the ACA, young adults had the highest rates of uninsurance among all age groups.31 A provision of the law allows young adults to remain covered through their parents’ health insurance through age 26. While this expansion in coverage benefits young adults, young women and teens may face additional barriers to contraceptive services as a result. Confidentiality is a priority for teens and young adults. In a national survey, 71% of women 18 to 25 rated confidentiality about use of health care such as family planning or mental health services as “important.” Despite the importance of confidentiality, awareness of this practice was low among this age group, as only 37% of women knew that private insurers typically send an EOB to primary policy holders, often a parent. Awareness is even lower among teens ages 15 to 18, where only 24% reported knowing that EOBs were typically sent to the home.32 Confidentiality also remains an issue for adult women who may be insured as a dependent through their spouse’s insurance Concerns over confidentiality may prompt some women to not use their private insurance to cover the cost of contraception and instead seek contraceptive services from publicly funded clinics, or forgo their preferred contraceptive methods.33 This creates additional barriers for women seeking contraception, placing them at increased risk for unintended pregnancy.

Some states have enacted laws aimed at protecting confidentiality for women and girls insured as dependents but they are limited to plans that are regulated by the state (small and large group and individual plans and not self-funded plans).34 In 2013 California passed a law, effective January 2015, requiring insurance companies to honor requests for confidential communications when individuals receive sensitive health care services, including contraception, or when disclosure could lead to danger. Similarly, in 2013, Washington amended regulations that prohibit insurers from disclosing EOBs to policyholders for all services for which minor patients may consent, unless the patient expressly authorizes disclosure. Colorado also amended regulations effective in 2014 to require insurers to protect the privacy of adult dependents, but not minors. Insurers in Colorado must communicate directly with the adult child or adult dependent so that protected health information is not sent to the policyholder in the form of an EOB without prior consent. Other states have developed other strategies to try to protect the privacy of dependents insured by a primary policyholder.

State laws regarding minors’ consent to contraceptive services pose another barrier.35 Half the states (26 states and the District of Columbia) explicitly allow all minors ages 12 and older to consent to contraceptive services. An additional 20 states explicitly allow only certain categories of minors to consent to contraceptive services and 4 states have no relevant policy or case law. Private clinics and doctors need to abide by any state laws regarding parental notification or minor consent. However, federal Title X protections take precedence over state requirements for parental consent or notification, allowing minors to receive family planning services at Title X clinics without parental involvement.36 So minors enrolled in plans that include Title X clinics in the network will be able to use their insurance and receive confidential services.

Access to Over the Counter Contraceptives without Doctor’s Prescription

The ACA only requires insurance plans to cover prescribed female contraceptives without cost-sharing and has no requirement for plans to cover over the counter methods including condoms, spermicide, and progestin-based emergency contraception (which is only covered with a prescription). Proposals to extend over the counter (OTC) status for oral contraceptives to expand women’s access to contraception, beyond progestin-based emergency contraceptive pills, have been gaining attention. FDA approval, however, is required to move more contraceptives over the counter, and members of Congress have introduced legislation addressing this issue.37 One bill seeks to waive fees and give priority FDA review specifically for manufactures seeing over the counter status for oral contraceptives to women 18 and older. A different bill specifies that if the FDA approves oral contraceptive for OTC, the ACA would be amended to include insurance coverage with no cost-sharing for these pills.

In addition, there have been efforts at the state level to broaden access to hormonal contraceptive. In 2013, California passed a law that allows pharmacists to prescribe pills, vaginal ring, and the patch for women. While this law does not change the OTC status for contraceptives, it allows women to access some prescription contraceptives without a doctor visit and still receive insurance coverage free of cost-sharing for these contraceptives. The law is expected to be fully implemented by the end of 2015. Oregon passed a similar law in July 2015 which allows pharmacists to prescribe hormonal oral contraceptives and the patch.

Coverage of Contraception for Men

While the ACA requires private insurance plans to cover FDA-approved contraceptives as prescribed for women without cost-sharing, this requirement does not include methods used by men: vasectomy and male condoms.38 Because the ACA provisions on contraceptive coverage only address services for women, tubal ligation and tubal implant are covered without cost-sharing, but there is no equivalent requirement to cover vasectomies without cost-sharing. In their recommendations for the provision of high quality family planning service, the CDC and the Office of Population Affairs have clearly stated that offering women and men the full range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods is a critical element of high quality care and emphasize the importance of contraceptive choice in reducing couple’s risk of unintended pregnancy.39 In addition, for many women, condoms or a vasectomy may be their preferred method. Over 22% of women report that male condoms were their primary contraceptive method and 9% of women report relying on their partner’s vasectomy.40 (Figure 1) Furthermore, condoms are the only method that protect against STDs, including HIV. Federal or state legislation, or action by insurance plans to voluntarily expand coverage for men would be needed to address this gap.

Oversight

State regulators and the federal government have a role in the oversight of private plans including covered benefits, coverage appeals, and network adequacy.

Covered Benefits and Appeals

State regulators have the responsibility to oversee most private health insurance plans while the Department of Labor oversees self-funded plans. State regulators and the federal government can monitor contraceptive coverage as required by the ACA when reviewing plan documents for rate review. While most states have taken action to develop review processes that meet federal standards, CMS reviews plans in five states that have been determined not to have an adequate rate review process.41

At this time, this oversight does not appear to include review of the insurance carrier’s waiver process for the coverage of contraceptive methods that are not included in the plans formulary for no-cost coverage. Federal guidance requires plans to have a “waiver” process for patients who have a medical need for contraceptives otherwise subject to cost-sharing or not covered.42 A KFF study found that none of the insurance carriers reviewed had established a formal process for policy holders to file a waiver contesting limitations on coverage for preventive services beyond their usual appeal process.43 The use of the standard appeal process can create a time delay for women seeking timely contraceptive services which could increase women’s risk of unintended pregnancy. This is particularly problematic for women who need timely access to emergency contraceptives not covered under the policy.

Network Adequacy

Another important provision related to all preventive services including contraceptive services is network adequacy. The provider networks of the Marketplace plans determine where enrollees can seek medical care. Many states have laws to help ensure that networks are adequate to meet consumers’ needs.44 The ACA also requires that consumers in Marketplace plans have a “sufficient choice of providers,” defined in the regulations as a right to networks that are sufficient in the “number and types of providers, including providers that specialize in mental health and substance abuse services, to assure all services will be accessible without unreasonable delay.” Narrow networks may make finding an available provider offering reproductive health services challenging for some women, especially if distance, time, and transportation barriers exist.

Marketplace plans must also include in their networks essential community providers (ECPs) that serve predominantly low-income, medically underserved individuals, including Title X clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers. ECPs often provide services that are specifically developed to address the health needs of low income individuals, including language services, patient support services, coordination of health and social services, and location in a low-income community. As noted above, minors can receive family planning services without parental involvement at Title X clinics. For women, particularly low-income women and women of color, clinic-based providers, family planning clinics and health centers are important sources of reproductive and sexual health care. Over one-quarter (28%) of women enrolled in Medicaid and 43% of uninsured women reported they had their most recent gynecological visit at either a clinic or health center.45 As many of these women gain insurance through Marketplace or employer-sponsored plans, community-based providers will continue to play an important role in reproductive health care.

It is unknown the extent to which state regulators and CMS are monitoring and enforcing federal and state network adequacy and ECP inclusion in Marketplace plans. As carriers are permitted to change networks during a plan year, the inclusion of ECPs in networks could change in the middle of a plan year. It is important to consider how federal and state oversight of the inclusion of ECPs can be ongoing and not just at the time of certification as a Qualified Health Plan.

Conclusion

The ACA has expanded contraceptive coverage without cost-sharing to millions of privately insured women across the nation. Ongoing consumer and provider education, continued oversight at the state and federal levels, and the resolution of the remaining legal challenges will determine how the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement is fully implemented.