Medicaid and Family Planning: Background and Implications of the ACA

Usha Ranji, Yali Bair, and Alina Salganicoff

Published:

Introduction

Introduction

Medicaid plays a primary role financing health care services and facilitating access to a broad a range of sexual and reproductive health services for millions of low-income women of childbearing age. Today it is the single largest source of public funding for family planning services, far exceeding the funding levels of the Federal Title X family planning program.1 States have long-been required to include family planning services in their Medicaid programs, but the shifts in health care delivery and reforms brought on by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are changing how these services are provided. While the ACA offers an opportunity to expand access to family planning services, it has challenged many family planning providers serving low-income populations to participate in changing systems of care in new ways. This brief reviews the role of Medicaid in financing and enabling access to family planning services for low-income women; discusses how states have expanded access to these services with Medicaid; and highlights future programmatic challenges in the context of the health care delivery and coverage reforms resulting from the ACA.

Medicaid and Women

Women make up a sizeable share of Medicaid enrollment. This is due to eligibility requirements that have roots in the welfare program formerly known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and efforts to expand insurance coverage to low-income pregnant women dating back to the 1980’s. In 2011, the most recent year for which there is national enrollment data, but prior to the 2014 ACA Medicaid coverage expansions, women and girls 15 and older represented a third of all Medicaid beneficiaries compared to a fifth for men (Figure 1).2

Among the 19.4 million women ages 15 and older with full Medicaid benefits in 2011, those in their reproductive years (ages 15 to 49) accounted for 70% of enrollment nationwide.3 For these 13.5 million women, Medicaid played a crucial role in coverage for family planning services and pregnancy-related care. The proportion of women enrolled in Medicaid who are reproductive age varies by state, ranging from 61% in New Jersey to a high of 80% in Delaware. These variations reflect differences in median income as well as state-defined program eligibility criteria, including for pregnancy-related care (Appendix 1).

Issue Brief

Medicaid Family Planning Policy

The manner in which family planning services are financed and organized is unique within the Medicaid program. All state Medicaid programs must offer some level of family planning benefits, and health care providers and pharmacies are not permitted to charge cost-sharing for family planning services. In most cases, beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid managed care networks may obtain family planning services from the provider of their choice (as long as the provider participates in the Medicaid program) even if they are not considered “in-network” providers. The federal government matches state family planning contributions to all participating providers at 90%, which is generally a higher rate than that offered for other services. This payment policy has been an incentive in state efforts to expand coverage for family planning services to individuals who have not been otherwise eligible for full scope Medicaid coverage.

Benefits

Family planning is classified as a “mandatory” benefit under Medicaid, meaning that all programs must cover family planning, but states have considerable discretion in identifying the specific services and supplies that are included in the program. There is no formal definition of family planning in the Medicaid program. Rather, federal law generally allows payment for “family planning services and supplies furnished (directly or under arrangements with others) to individuals of child-bearing age (including minors who can be considered to be sexually active) who are eligible under the State plan and who desire such services and supplies.”1 Contraception is one of the primary services included as family planning, and most states offer broad coverage for prescription contraceptives in their Medicaid programs.

Over time, the clinical context of family planning has evolved to include a broader array of services, such as health education and promotion, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, and services that facilitate fertility preservation.2 These services are classified as “related family planning services” and also qualify for a 90% federal match if they are provided in the context of a visit to obtain family planning services (often synonymous with contraceptive care). Today, state Medicaid family planning programs may be limited to only those services that directly prevent or delay pregnancy or they may include additional benefits that facilitate reproductive decision-making or fertility preservation. For example, while all states cover prescription contraceptives under the family planning benefit, some states also pay for over-the-counter supplies and drugs, counseling, and STI screening and treatment.3 While state Medicaid programs make determinations about the services that they will cover, for many women, particularly those enrolled in capitated managed care arrangements (discussed further in this brief), coverage policies are established through the contracts that plans sign with the state program. In addition, plans can use medical management techniques to limit or exclude specific benefits by using prior authorization requirements, concurrent review, or similar practice. This allows a plan or issuer to determine the frequency, method, treatment, or setting for the provision of a particular health service. For example, in the case of contraception, providers or a Medicaid program can rely on generics or direct patients to first try less expensive methods before moving on to more costly methods that may be more effective.

Medicaid and sterilization

Most Medicaid programs pay for sterilization services. Federal law requires that Medicaid programs impose a 30-day waiting period between the time a woman signs a consent form for sterilization and the time when the procedure may be performed. This policy is a response to coercive practices used to sterilize certain groups of women–particularly those with mental illness and women of color–during the 1970s and earlier in the 20th century. This policy was put in place to assure that women have had time to thoroughly weigh their options prior to consenting to this permanent decision. While serving as an important protection to women, the waiting period policy has also, in some cases, impeded access to sterilization, particularly for women seeking to have the procedure done during the post-partum hospital stay.4

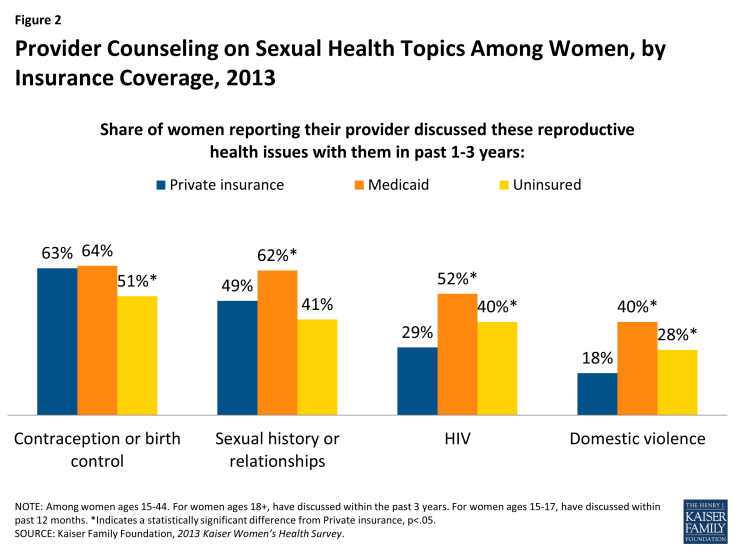

In April 2014, the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued the report, Providing Quality Family Planning Services (QFP), the first joint agency recommendations targeted for service providers outlining the elements of high quality family planning care. The recommendations identify and define a core set of family planning services for women and men; describe how to provide services; and encourage the integration of a family planning visit with preventive services. The OPA and CDC recommend that core family planning care include services to prevent pregnancy and space births. One of the most important developments in this framework was the attempt to direct women to the most effective and appropriate contraceptive methods. In addition, the core family planning services also include the provision of pregnancy testing and counseling, basic infertility services, STI and HIV services, and other preconception services such as screening for obesity, smoking, and mental illness.5 While these services are recommended as elements of high quality family planning care there is no requirement that all state Medicaid programs offer them to their beneficiaries. In 2013, however, women with Medicaid coverage were more likely than women with private insurance to report they had spoken with a provider about sexual history, HIV and intimate partner violence (Figure 2).6

Financing

To encourage states to expand the family planning services offered under Medicaid, the federal government has paid for 90% of state expenditures for all family planning services and supplies since 1972.7 In addition, federal policy specifically prohibits cost sharing for any family planning services. Although expenditures for family planning services and supplies comprise only 0.03% of overall Medicaid program expenditures, with this relatively modest investment, Medicaid has become the leading source of public financing for family planning services for low-income women.8 Over the course of the last quarter-century, Medicaid’s importance as a source of public financing for family planning has risen considerably, accounting for just 14% of all public funds spent to provide contraceptive services and supplies in 1999 and rising to 75% in 2010, far surpassing funding levels from the federal Title X family planning safety net program.9,10 This shift has been largely attributable to programmatic changes in Medicaid that have allowed states to establish separate programs to provide coverage for a limited set of Medicaid funded family planning services to low-income women who do not qualify for full scope Medicaid benefits (discussed in a following section). Title X funding has been reduced for the past few decades, making it challenging for the program to keep up with the rising costs of delivering care.

Family Planning Providers

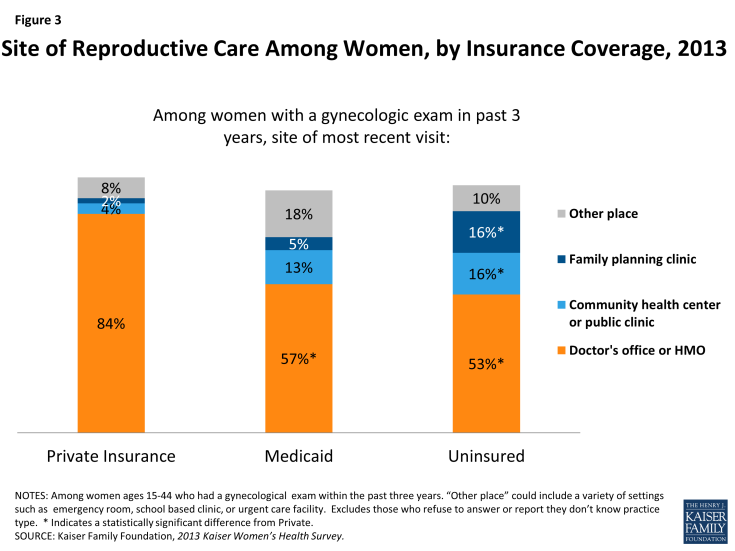

Women receive their sexual and reproductive health care from a range of providers, including private physicians, federally qualified health centers, family planning clinics, health departments and other clinics. According to the Kaiser Women’s Health Survey,11 women with Medicaid coverage and uninsured women are more likely to rely on community health centers and family planning clinics, than those with private insurance (Figure 3). However, office-based physicians or HMOs are still the leading sites of gynecologic care for women. About eight in ten women of reproductive age with private insurance (84%) receive gynecologic care at a doctor’s office or HMO, compared to about half of women with Medicaid coverage (57%) and uninsured women (53%).

Managed Care

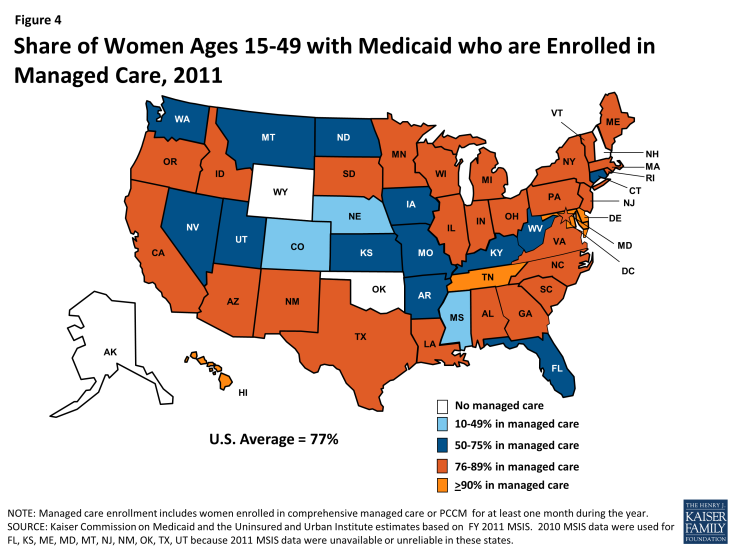

In their efforts to expand access to providers, coordinate care, and control spending, many state Medicaid programs have turned to managed care delivery systems to provide care. These arrangements can be broadly organized into either fully capitated networks of limited providers or more loosely structured primary care case management systems where a primary care provider is a gatekeeper to care. Today the vast majority (77%) of reproductive age women receiving full scope Medicaid coverage are enrolled in some type of managed care arrangements (Figure 4). This ranges from no women in managed care in Alaska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Wyoming to 13% in Mississippi to most women in this age group in Tennessee, Hawaii, Delaware, and Maryland (Appendix 2).12

Many states require Medicaid beneficiaries to enroll in managed care and receive services from a defined network of providers, but a few states allow women to choose to between a managed care plan or a fee for service system. In cases where managed care enrollment is mandatory, women enrolled in these plans may seek family planning care from the provider of their choice – even if they are outside the plan network — as long as the provider participates in the Medicaid program in their state. However, implementation of this federal “freedom of choice” provision13 has been challenging for patients, providers and health plans. Medicaid beneficiaries are often unaware that they have a choice of family planning provider and there is no clear standard about who (health plan or the state) is responsible for informing them about their provider options. Providers and health plans often have had difficulty negotiating and setting appropriate reimbursement for family planning services. This is particularly challenging to implement for those enrolled in fully capitated networks where provider payments are bundled and/or provided in advance, making reimbursement to out-of-network providers more complicated.

Medicaid Family Planning Programs

Over 20 years ago, states began establishing special demonstration programs that allowed them to offer Medicaid eligibility for a limited scope of services or to a specific population. For several years, these narrow scope programs were established as Section 1115 waivers, time-limited research demonstration projects that had to be approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to give states the flexibility to waive certain Medicaid rules so they can design new systems to expand and improve their Medicaid programs. Several states have used waivers to provide coverage for family planning services only to women and men who do not qualify for full Medicaid benefits. Federal rules required that the programs must be budget neutral, meaning that they may not cost the federal government any more than they would have otherwise paid the state absent the change. They also required that the effectiveness of the change be evaluated.

Initially, family planning waiver programs extended coverage for family planning services to women who no longer qualified for Medicaid due to changes in income or because they were no longer eligible for maternity coverage. Other states opted to extend coverage to low-income women of reproductive age, regardless of their prior Medicaid eligibility status. In 2011, at least 3.5 million women ages 15 to 49 obtained Medicaid-covered family planning services through family planning waivers.14 While the waiver system was instrumental in expanding access to family planning services, states were required to renew them every five years, which posed a significant financial and administrative burden on states. As “research and demonstration” programs, the waivers have been subject to rigorous evaluation and have proven cost-effective and successful in improving public health outcomes.15,16, 17 In the more than 20 years that states have been operating these program, they have moved out of the realm of demonstration projects and are now functioning as safety net family planning programs in many states, particularly in California which has the nation’s largest enrollment.

Recognizing the importance of these programs and the administrative challenges that states faced in initiating and renewing their waivers, the ACA included a provision that enabled states to establish family planning expansion programs by permanently amending their Medicaid state plans, known as a State Plan Amendment (SPA) without the need for federal renewal. In response, many states have converted their waiver programs to SPAs rather then seeking renewal of their waivers and others have newly decided to establish SPAs to broaden access to family planning services for low-income women. Today, more than half of states have established programs that extended Medicaid eligibility for family planning services to people who would not otherwise qualify for Medicaid, and as of January 2016, 14 states have adopted family planning SPAs (Appendix 3). Income-based eligibility is the only approach used in SPAs.

State Profile: Family PACT in California

California’s Family Planning, Access, Care, and Treatment (Family PACT) Program was originally established by the California legislature in 1996 and funded through the California State General Fund. When the state transitioned the program to a Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver, the state received federal matching funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). In 2011, after the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) created the SPA option, California incorporated the Family PACT Program into its Medicaid program. Family PACT is by far the largest family planning expansion program in the nation, serving 1.83 million men and women in Fiscal Year 2011-2012. The program provides a variety of services, including contraceptives, counseling, and STI testing to women and men, it also provides mammograms to women 40 and older. It is estimated that over half (54%) of women ages 15-44 in need of publicly funded contraceptive services received these services through Family PACT in FY 2011-12.18 In 2009, the Family PACT program was estimated to have averted approximately 200,041 unintended pregnancies. The state also estimated that each unintended pregnancy averted saved the public sector approximately $5,469 in medical, welfare, and other social service costs for the woman and their child. Over five years, Family PACT saved the public sector approximately $14,111 per averted pregnancy, for a total of nearly $4.08 billion in savings.19

The ACA, Medicaid Expansion, and Family Planning

In 2010, the ACA paved the way for the biggest Medicaid policy changes since the program’s inception in 1965. The ACA allows states to broaden Medicaid eligibility, creating a foundation of coverage for nearly all low-income Americans with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($11,770 per year for an individual in 2015). Prior to the ACA, women could qualify for Medicaid only if their incomes were very low and they belonged to one of Medicaid’s categories of eligibility – pregnant, parent, senior, or disability. Many low-income women would qualify only after becoming pregnant. With the ACA’s elimination of the categorical eligibility, low-income women who are not pregnant nor have children could qualify for Medicaid coverage. The 2012 Supreme Court ruling on the ACA, however, effectively made this Medicaid expansion optional for states, resulting in inconsistent coverage policies across the nation. As of January 2016, 31 states plus DC have expanded eligibility for Medicaid, while the remaining 19 states are not moving forward with the ACA Medicaid expansion at this time.1

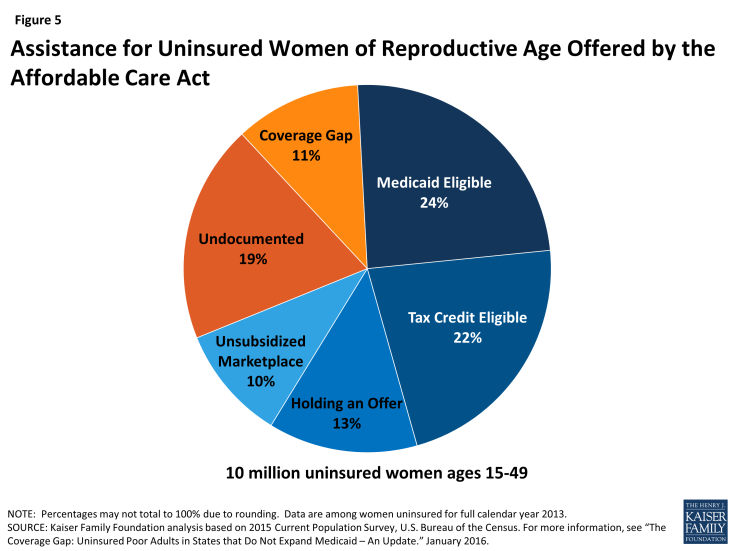

Of the 10 million women ages 15 to 49 who were uninsured during 2014, it is estimated that about 4.7 million qualify for either Medicaid or ACA marketplace subsidies and could gain coverage as the ACA becomes fully implemented in the coming years. An additional 1.1 million women with incomes below the federal poverty level have no pathway to affordable coverage, however, because they live in a state that is not expanding Medicaid. It is likely that there are at least an additional 1.9 million women of childbearing age who will remain ineligible for Medicaid or marketplace participation due to their immigration status (Figure 5).2

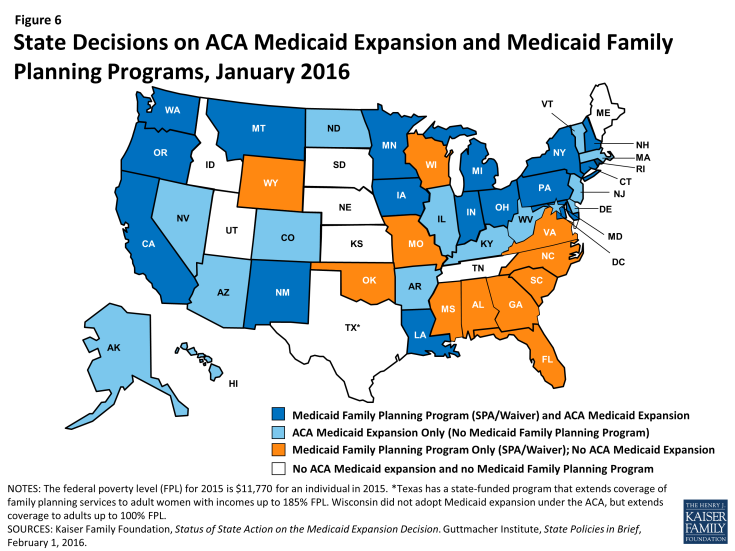

State decisions about implementing the ACA Medicaid expansion have important policy and fiscal implications for family planning. Of the five states with the highest number of uninsured individuals, only California and New York have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion and the remaining three, Texas, Florida and Georgia, have not.3 Currently, of the 28 states with Medicaid family planning programs, 17 are in states that have also moved forward with ACA Medicaid expansions and 11 are in states that have not chosen to expand Medicaid (Figure 6). In states that implement the ACA Medicaid expansion, individuals who were relying on family planning providers as their primary source of care will gain coverage for a full range of health care services and have access to a broader network of health care providers.

Figure 6: State Decisions on ACA Medicaid Expansion and Medicaid Family Planning Programs, January 2016

In the states that have not expanded their full scope Medicaid programs under the ACA, Medicaid family planning programs have the potential to play a significant role for low-income individuals, mostly women, who will not have a pathway to affordable coverage and will likely remain uninsured. For some low-income women living in these states, the Medicaid family planning programs will provide them with access to a limited set of health care services, including contraception and other preventive services. For the women living in the nine states that have chosen not to expand their full scope Medicaid programs and do not have Medicaid family planning expansion programs, safety net programs, charity care, and emergency departments will likely be their only sources of care. In all states, however, there still will be a sizable minority of individuals who remain uninsured for a variety of reasons, including immigration status and the absence of affordable coverage options. These women will also depend on the services of safety-net providers for care.

State Profile: Expanded Access to LARCs in Colorado

Colorado has adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion for low-income residents up to 138% FPL. Colorado, however, does not have a separate family planning expansion program. The state is large and geographically diverse, with populations in need of subsidized family planning services located both in dense urban centers and remote rural areas. Approximately one in four women living in the state have incomes below 150% of the federal poverty level and more than half of these are below the age of 25. In 2008, prior to the passage of the ACA, the state created the Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CFPI). This program is separate from Medicaid and was designed to increase access to family planning and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) in particular, for low-income, uninsured women in the state, including those who might not have qualified for Medicaid prior to the ACA expansion.4 Using a combination of significant private donations and public Title X funds, the state invested in provider infrastructure, patient education and outreach and coverage for effective (but expensive) long-acting reversible contraceptives. Despite its success, the future of this program is not secure, as the state is currently debating whether to use state funds to continue the CFPI. In 2010, the Colorado Department of Public Health chose reduction in unintended pregnancy as a “winnable battle” and identified this as one of the prevention division’s top two priorities. The state’s efforts have paid off according to the Department of Public Health, which credits the family planning program with prevention of 27,000 unintended pregnancies annually.5

States that have chosen to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion for low-income adults are required to define benefits for newly eligible beneficiaries through the Alternative Benefit Plan (ABP) mechanism. The ABP may also be used to define a different scope of benefits from specific populations in traditional full scope Medicaid programs, resulting in variations in benefits between covered populations within states and between states. In the ACA Medicaid expansion states, many women receiving services through Medicaid family planning programs may qualify for a broader set of services through full scope ACA Medicaid eligibility expansions. The law specifies that individuals who are newly eligible for coverage under the ACA Medicaid expansion receive a benchmark benefit package that must include ten “essential health benefits,” including preventive services at no cost to the patient. 6

Preventive services now are defined to include all of the 18 FDA approved contraceptive methods, as prescribed, as well as all of the services recommended by the federally commissioned U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which include counseling on STIs and HIV and screening for breast and cervical cancers. However, this may vary from what is covered for women who would have been eligible for either full scope Medicaid or a Medicaid family planning program prior to the ACA expansions (Appendix 4). This is because the package of services that states may offer through their traditional full scope Medicaid program and through Medicaid family planning programs are not required to comply with the ABP. Some states may not cover all FDA approved contraceptives or all of the USPSTF services under those programs since there are no specific federal minimum requirements for traditional full scope Medicaid to do so.

State Profile: State-funded family planning program in Texas

Texas runs a state-funded program called the Women’s Health Program (WHP) that provides family planning services to women between 18 and 44 years of age with incomes up to 185% FPL who are not pregnant. The WHP originated in 2007 as an 1115 Medicaid Family Planning Waiver Demonstration. Since its inception in 2007, the program has grown ten-fold from 9,300 enrolled women to 132,000 women at its peak in August 2011. In 2011, the range of providers eligible to participate in the program plummeted when the Texas legislature directed the Health and Human Services Commission to establish the “Affiliate Ban Rule,” which prohibited organizations performing abortions, including all Planned Parenthood affiliated clinics, from participating in the WHP. As a result, on March 15, 2012, CMS informed Texas that the state waiver would not be extended or renewed because the Affiliate Ban Rule” did not comply with CMS’ “freedom of choice” policy which permits Medicaid beneficiaries the option of getting their care from any participating Medicaid provider. In order to maintain the WHP, Texas transitioned it from a federally and state funded Medicaid waiver demonstration to a program funded with state-only funding and without any federal support or affiliation with Medicaid. The program offers a limited scope of services, including counseling, certain screening services, and free contraceptives. The number of family planning organizations funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services fell from 76 to 41 in the past two years and even some of the largest organizations continuing to receive funding have lost up to 75% of their budgets.7 It has been estimated that tens of thousands of low-income Texas women have lost access to family planning services and other women’s health services, possibly resulting in an increase in unplanned pregnancies around the state. 8

Future Challenges

In the coming years, state choices about whether or not to expand full scope Medicaid eligibility under the ACA or whether to establish or maintain limited scope Medicaid family planning programs will shape how most low-income women gain access to family planning services. Furthermore, the range of available benefits and contraceptive methods may vary for women who have Medicaid funded family planning services. Those who qualify for the full scope Medicaid under the ACA expansion may have benefits that differ from those who qualify based on either traditional full scope Medicaid rules or through Medicaid family planning programs. Services that are claimed as a “family planning service,” will continue to be exempt from cost sharing charges, and states may claim a 90% federal match for beneficiaries enrolled in traditional full-scope Medicaid or a Medicaid family planning program. The federal government pays at least 90% of the cost for all services delivered to beneficiaries who qualify under the ACA Medicaid expansion.

The following sections highlight key challenges facing state and federal Medicaid officials, policy makers, and providers as they shape Medicaid-funded family planning services in the future.

Ensuring Contraceptive Choices for Women

Variations in Coverage across Medicaid eligible groups: Federal ACA rules and state level Medicaid policy decisions have created multiple coverage populations that are subject to different eligibility rules and benefit packages. Federal statute requires states to cover “family planning services and supplies,” but does not specifically define these services. States have a fair amount of flexibility in defining the specific family planning services and could offer different levels of benefits for different groups of women depending on the type of Medicaid program they qualify for. As discussed earlier, the ACA defines a set of essential health benefits that must be offered to newly eligible individuals under the Medicaid ACA expansions, but there is no minimum requirement for the specific servcies that traditional full scope Medicaid must offer. In particular, women who obtain ACA Medicaid coverage are entitled to no-cost coverage of the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives, while traditional Medicaid programs are not required to cover the full range. Furthermore, women covered in ACA Medicaid plans receive no-cost coverage for other preventive services such as screening for cervical and breast cancers, which are considered “optional” under traditional Medicaid, although many states have chosen to cover these services.1 A standardized federal definition of family planning services could facilitate state policymaking in this arena, but in the absence of such guidance, some have proposed that the essential health benefits required in ACA Medicaid expansions could be a reasonable benchmark for standardization. In addition to state Medicaid benefits rules, Medicaid managed care plans typically employ cost reduction or utilization management techniques that can further differentiate family planning benefits offered to Medicaid beneficiaries, particulary when it comes to contraceptives. This could result in a range of benefits that are available to women enrolled in different plans or living in different parts of the same state.

Medical Management: Another key issue for family planning care is medical management under pharmacy benefits. The FDA has identified 20 different contraceptive methods, and the contraceptive coverage rule specifies that plans must cover all methods, as prescribed.2 Women enrolled in these plans must be offered coverage of their method of choice without cost sharing, but coverage of these methods can be restricted by other means. Contraceptive drugs and supplies in Medicaid and in most health plans are treated as a prescription drug benefit and are subject to the same formulary restrictions as other drugs. Contraceptives are often subject to formulary cost reduction strategies such as step therapy or “fail-first” trials. These methods require patients to try a variety of methods or generic brands, and often to prove “failure” of a particular method in order to obtain coverage for a higher tier or more expensive therapy. In the case of contraception, the contraceptive “failure” could mean an unintended pregnancy, and could result in higher costs for the Medicaid program in the long-run. A California law addresses some of the potential ambiguity of medical management limitations by requiring that all private plans and Medicaid managed care plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing.3

Religious Exemptions: As the health care system moves toward more integrated care, centered on primary care, sensitive services such as family planning may require careful attention. This is especially true for women who are enrolled in faith-based plans or providers that have religious objections to some or all methods of contraception. Medicaid programs are faced with ensuring appropriate and timely referrals for women enrolled in faith-based health plans or provider networks that may limit women’s access to services by exercising a “conscience exemption.” Meaningful implementation of the federal freedom of choice provision in Medicaid managed care plans has become increasingly important as enrollment in faith based networks grows. This means that assuring that women have access to services meet the full range of their health care needs, including sexual and reproductive care, while maintaining confidentiality and quality, which will continue to be important to the women who receive services funded by the Medicaid programs across the nation.

Provider Networks: Medicaid family planning programs will continue to be an important avenue for ensuring access to reproductive health services for low-income individuals during these transitional periods. In states with Medicaid family planning programs, health centers are more likely to offer clients access to a wide range of contraceptive options than health centers in states without public family planning programs.4 Family planning health centers can play a critical role in ensuring continuity of care for low-income women of reproductive age who need reproductive health services over a long period of time. States have established network adequacy rules that are designed to assure that provider networks include the full range of providers that Medicaid beneficiaries need to address their health needs. Furthermore, the inclusion of existing family planning providers in both Medicaid managed care and other service delivery networks can be an effective strategy to maintain continuity of care and consistent contraceptive use in settings that offer high quality confidential services. Women seeking care within networks or out of network through federal “freedom of choice” rules may want to continue seeing family planning providers to meet their contraceptive care needs. Another important consideration for network adequacy however, is low provider payment, leaving providers to struggle with the costs of delivering services in many regions or providers who do not participate in the program due to low payments.

Payment Issues

Low Rates: On average, state Medicaid programs pay providers much lower reimbursement than private insurers and subsequently Medicaid provider reimbursement has not kept up with the cost of delivering services.5 Payment levels vary between states and access to providers has been particularly challenging in the states that pay the lowest rates.6 Payment levels also vary between programs, with some states paying higher reimbursement in family planning expansion programs compared to full scope Medicaid. With millions more women joining the Medicaid program under the ACA’s expansion, there will be more demand for provider availability. Addressing payment rates is an important factor in securing access to providers for women with Medicaid coverage.

Post Pregnancy Contraception: More than half of repeat pregnancies with short pregnancy intervals (less than 18 months) are unintended. Close spacing of pregnancies puts women and their children at greater risk for complications such as low birth weight, preterm birth and preeclampsia.7 An estimated 14 to 35% of adolescent mothers become pregnant again within one year of delivery, despite intention to use contraception.8 Sterilization and long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) such as IUDs are the most effective methods for preventing pregnancy, and access to LARCs has been recommended by a number of professional associations for post-partum women. Historically, IUDs have been among the most expensive contraceptive methods, and access to post-pregnancy sterilization and LARC methods for some post-partum women has been complicated because payment for obstetric services is typically “bundled.” This means that the costs of the LARC and the insertion and related services may not be accounted for in that “bundled” payment, and consequently there is a disincentive for providers to offer this highly effective but costly method to post-partum women. A number of states have initiated policies to facilitate reimbursement of LARCs to post-partum women but it is still difficult to administer in many states.9 Access to sterilization has been challenging for some women with Medicaid who are still in the hospital after a delivery because they may have not met the 30-day waiting period requirement, a policy designed to protect them from coercion.

Discounted Drug Pricing: Many family planning clinics and safety net providers that participate in Medicaid rely on Medicaid program discounts as well as the 340B Drug Pricing Program to get the best prices for contraceptive supplies for women. The 340B program, established in 1992 to provide discounted prescription outpatient drugs for safety net providers, has grown over time, involving a larger and more diverse set of providers such as family planning clinics.10 Clinics that participate in the 340B program must follow an increasingly complex set of regulations from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the agency that administers the 340 B program as well as CMS, which administers Medicaid. Family planning providers have relied on 340B contraceptive discounts to maximize resources when caring for patients with diverse payer sources. Currently, providers that use 340B pricing must do so for all prescriptions, but some representatives of family planning clinics are advocating for structural changes that would allow providers and Medicaid programs the flexibility to decide how and when to apply 340B discounts on an individual case basis. They are claiming these changes would help states and providers maximize resources and keep up with the changing drug coverage and reimbursement landscape.

Assuring Continuity and Quality of Care

Transitions in Coverage: For millions of women who have been uninsured or who only have had access to periodic or limited benefits, the promise of continuous full-scope Medicaid enrollment is an important step toward stable health care. Some proportion of these individuals will, however, experience gaps or difficult coverage transitions, potentially disrupting their continuity of care and established relationships with providers. Research has found that approximately half of low-income individuals could experience fluctuations in income or family circumstance in a year, which could lead to vacillation in eligibility for Medicaid and state Marketplace plans.11 Because continuity of care and patient-centered decisions are key for successful family planning programs and for effective use of contraception, systems designed to assure smooth coverage transitions will be critical to assure that women don’t experience disruptions in contraceptive coverage, which could result in interruptions in contraception use or in the use of less reliable methods, and put women at higher risk for experiencing unintended pregnancies.

Counseling and Education: Medicaid programs have increasingly invested in patient education and self-management initiatives for chronic disease, often relying on non-clinician team members to deliver high quality education and counseling. Reimbursement policies that include support for patient self-management and informed decision-making are becoming an important cost reduction and quality improvement tool for health plans and in Medicaid programs.12 In this vein, patient-centered family planning is critical to successful contraception use. Contraceptive counseling and education are important benefits that can be reimbursed under current family planning program rules in most states and are important elements of comprehensive family planning services.

Quality Standards: Medicaid programs and managed care health plans have been moving toward value-based reimbursement mechanisms that rely on measures of high quality care. The development of quality measures and payment systems that include benchmarks that assess women’s health and family planning care are lagging. The new federal recommendations for quality family planning services outline specific performance measures and data collection methods to evaluate the provision of the quality of care and could be the foundation for the development of family planning quality of care measures.13 The application of evidence-based clinical and utilization measures specific to family planning would allow Medicaid programs, the largest payers of family planning in the nation, to improve the quality of women’s health services. Standardization of family planning services to meet quality benchmarks could increase the quality of care by assuring that the array of services available in every state meets the full range of women’s contraceptive and sexual health needs.

The Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) is collaborating with the CDC to develop contraception-related measures as part of its Maternal and Infant Health Initiative.14 One of the two current priorities for the initiative is to increase the use of highly effective contraception by 15% over a 3-year period. To this end, the initiative has developed and validated two new contraceptive measures. These measures are the percentage of female clients ages 15 to 44 at risk of unintended pregnancy that adopt or continue use of 1) the most effective or moderately effective FDA-approved methods of contraception and 2) an FDA-approved, long-acting reversible method of contraception (LARC). Using data from the National Survey of Family Growth as a benchmark, the initiative offers support to states as they develop reporting capacity around these new measures.

Conclusion

As the ACA implementation progresses and matures, the role of Medicaid in financing family planning services for low-income women will only grow. Medicaid expansion offers an opportunity to broaden access to sexual and reproductive health services for low-income women. As states implement various provisions of the ACA, the role of Medicaid in women’s health and health care must be carefully considered. Gaps in coverage, inconsistent benefits, and difficulties accessing care can translate to disruptions in care that can lead to negative reproductive outcomes including unintended pregnancies. As delivery systems under Medicaid evolve and become more complex, it will be important to develop policies that support and include the wide range of reproductive and sexual health services that women need, from the providers that offer the highest quality confidential care. Medicaid family planning programs have demonstrated that they can improve health outcomes and reduce costs associated with unintended pregnancies. The ACA provides an opportunity for the Medicaid program to sustain the progress and accomplishments that the program has already attained in family planning and to be on the vanguard of programs that advance women’s reproductive health in the future.

This brief was prepared by Usha Ranji of the Kaiser Family Foundation, Yali Bair of Ursa Consulting, and Alina Salganicoff of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Women with Full Medicaid Benefits and Share that are Reproductive Age, by State

| Appendix 1: Women with Full Medicaid Benefits and Share that are Reproductive Age, by State, 2011 | |||

| State |

Total Number of Women Ages 15 and Older Enrolled in Medicaid with

Full Benefits

|

Number of Women with Medicaid who are

Reproductive Age

(ages 15 to 49)

|

Reproductive Age Women(ages 15 to 49) as Share of Adult Women with Medicaid |

| U.S. Total | 19,403,918 | 13,543,835 | 70% |

| Alabama | 208,642 | 132,041 | 63% |

| Alaska | 43,916 | 33,157 | 76% |

| Arizona | 415,949 | 310,873 | 75% |

| Arkansas | 168,176 | 114,267 | 68% |

| California | 2,673,412 | 1,692,124 | 63% |

| Colorado | 233,451 | 178,665 | 77% |

| Connecticut | 275,407 | 198,813 | 72% |

| Delaware | 78,560 | 62,627 | 80% |

| DC | 86,572 | 59,874 | 69% |

| Florida | 1,011,048 | 713,681 | 71% |

| Georgia | 529,780 | 399,116 | 75% |

| Hawaii | 100,824 | 69,827 | 69% |

| Idaho | 61,462 | 44,759 | 73% |

| Illinois | 1,031,364 | 779,393 | 76% |

| Indiana | 325,604 | 234,323 | 72% |

| Iowa | 189,851 | 136,180 | 72% |

| Kansas | 112,596 | 76,863 | 68% |

| Kentucky | 291,330 | 205,244 | 70% |

| Louisiana | 301,117 | 208,081 | 69% |

| Maine | 135,229 | 95,458 | 71% |

| Maryland | 303,690 | 231,873 | 76% |

| Massachusetts | 423,898 | 270,992 | 64% |

| Michigan | 747,090 | 552,681 | 74% |

| Minnesota | 375,526 | 270,365 | 72% |

| Mississippi | 192,769 | 124,873 | 65% |

| Missouri | 364,969 | 250,360 | 69% |

| Montana | 31,309 | 19,880 | 63% |

| Nebraska | 88,801 | 61,177 | 69% |

| Nevada | 95,078 | 74,526 | 78% |

| New Hampshire | 52,955 | 37,783 | 71% |

| New Jersey | 308,418 | 188,028 | 61% |

| New Mexico | 130,835 | 100,973 | 77% |

| New York | 1,958,958 | 1,286,194 | 66% |

| North Carolina | 527,080 | 357,355 | 68% |

| North Dakota | 29,919 | 21,525 | 72% |

| Ohio | 790,018 | 598,985 | 76% |

| Oklahoma | 249,044 | 174,367 | 70% |

| Oregon | 183,011 | 132,329 | 72% |

| Pennsylvania | 853,488 | 585,602 | 69% |

| Rhode Island | 69,420 | 47,163 | 68% |

| South Carolina | 304,332 | 210,599 | 69% |

| South Dakota | 33,765 | 24,207 | 72% |

| Tennessee | 508,357 | 392,654 | 77% |

| Texas | 1,031,040 | 733,598 | 71% |

| Utah | 93,020 | 73,215 | 79% |

| Vermont | 64,428 | 45,444 | 71% |

| Virginia | 317,111 | 225,641 | 71% |

| Washington | 373,749 | 281,030 | 75% |

| West Virginia | 142,072 | 98,673 | 69% |

| Wisconsin | 462,474 | 308,334 | 67% |

| Wyoming | 23,004 | 18,043 | 78% |

|

NOTES: This table shows the number of people with full Medicaid benefits for at least 1 month in 2011. Enrollees whose age was not provided or whose gender was unknown were excluded from the data, accounting for less than 1% of all enrollees. Due to data quality issues, individuals with disabilities in Maine who were enrolled in Medicaid only in Q4 are not included in totals.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and Urban Institute analysis of FY 2011 MSIS. 2010 MSIS data were used for FL, KS, ME, MD, MT, NJ, NM, OK, TX, and UT because 2011 data were unavailable or unreliable in these states.

|

|||

Appendix 2: Women Ages 15 to 49 Enrolled in Medicaid Managed Care Arrangements, by State

| Appendix 2: Women Ages 15 to 49 Enrolled in Medicaid Managed Care Arrangements, by State, 2011 | |||

|

Total Number of Women Ages 15 to 49 Enrolled in Medicaid with

Full Benefits

|

Women with Medicaid Full Benefits Ages 15 to 49

in Managed Care (PCCM or Comprehensive Models)

|

||

| State | Enrollment | Enrollment |

Share of All Women

Ages 15 to 49

|

| U.S. Total | 13,543,835 | 10,405,826 | 77% |

| Alabama | 132,041 | 109,998 | 83% |

| Alaska | 33,157 | 0 | 0% |

| Arizona | 310,873 | 274,892 | 88% |

| Arkansas | 114,267 | 79,041 | 69% |

| California | 1,692,124 | 1,319,995 | 78% |

| Colorado | 178,665 | 29,358 | 16% |

| Connecticut | 198,813 | 147,204 | 74% |

| Delaware | 62,627 | 59,143 | 94% |

| DC | 59,874 | 50,211 | 84% |

| Florida | 713,681 | 475,553 | 67% |

| Georgia | 399,116 | 337,435 | 85% |

| Hawaii | 69,827 | 67,816 | 97% |

| Idaho | 44,759 | 36,591 | 82% |

| Illinois | 779,393 | 615,144 | 79% |

| Indiana | 234,323 | 206,452 | 88% |

| Iowa | 136,180 | 77,872 | 57% |

| Kansas | 76,863 | 50,798 | 66% |

| Kentucky | 205,244 | 154,090 | 75% |

| Louisiana | 208,081 | 166,459 | 80% |

| Maine | 95,458 | 72,997 | 76% |

| Maryland | 231,873 | 208,336 | 90% |

| Massachusetts | 270,992 | 214,025 | 79% |

| Michigan | 552,681 | 435,760 | 79% |

| Minnesota | 270,365 | 211,050 | 78% |

| Mississippi | 124,873 | 16,379 | 13% |

| Missouri | 250,360 | 133,352 | 53% |

| Montana | 19,880 | 14,469 | 73% |

| Nebraska | 61,177 | 29,278 | 48% |

| Nevada | 74,526 | 50,301 | 67% |

| New Hampshire | 37,783 | 0 | 0% |

| New Jersey | 188,028 | 162,617 | 86% |

| New Mexico | 100,973 | 77,327 | 77% |

| New York | 1,286,194 | 1,064,825 | 83% |

| North Carolina | 357,355 | 313,319 | 88% |

| North Dakota | 21,525 | 13,984 | 65% |

| Ohio | 598,985 | 522,042 | 87% |

| Oklahoma | 174,367 | 0 | 0% |

| Oregon | 132,329 | 115,435 | 87% |

| Pennsylvania | 585,602 | 521,071 | 89% |

| Rhode Island | 47,163 | 36,399 | 77% |

| South Carolina | 210,599 | 173,751 | 83% |

| South Dakota | 24,207 | 19,939 | 82% |

| Tennessee | 392,654 | 392,654 | 100% |

| Texas | 733,598 | 589,650 | 80% |

| Utah | 73,215 | 37,282 | 51% |

| Vermont | 45,444 | 38,987 | 86% |

| Virginia | 225,641 | 173,950 | 77% |

| Washington | 281,030 | 206,297 | 73% |

| West Virginia | 98,673 | 59,935 | 61% |

| Wisconsin | 308,334 | 242,363 | 79% |

| Wyoming | 18,043 | 0 | 0% |

|

NOTES: Managed care enrollment includes women enrolled in comprehensive managed care or primary care case management (PCCM). All counts indicate that an enrollee was enrolled for at least one month in that type of insurance. Excludes “Other Types of Managed Care” such as dental, behavioral, family planning, long-term care, or other non-comprehensive and non-PCCM types of managed care.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and Urban Institute analysis of FY 2011 MSIS. 2010 MSIS data were used for FL, KS, ME, MD, MT, NJ, NM, OK, TX, and UT because 2011 data were unavailable or unreliable in these states.

|

|||

Appendix 3: States that have Expanded Eligibility for Coverage of Family Planning Services Under Medicaid

| Appendix 3: States that have Expanded Eligibility for Coverage of Family Planning Services Under Medicaid | |||||

| State | Organized as a Waiver or State Plan Amendment (SPA) | Basis for Eligibility | Includes Men | Includes Teens (<19) | Waiver Expiration Date |

| Alabama | Waiver | Income; 146% FPL | Yes | No | 12/31/2017 |

| California | SPA | Income; 200% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Connecticut | SPA | Income; 263% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Florida | Waiver | Women losing Medicaid post-partum; 2-year limit | No | Yes | 12/31/2017 |

| Georgia | Waiver | Income; 200% FPL | No | No (includes 18 year olds, but not younger teens) | * |

| Indiana | SPA | Income; 146% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Iowa | Waiver | Income; 300% FPL | Yes | Yes | 12/31/2016 |

| Louisiana | SPA | Income; 138% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Maryland | Waiver | Income; 200% FPL | No | Yes | 12/31/2016 |

| Michigan | Waiver | Income; 185% FPL | No | No | 6/30/2016 |

| Minnesota | Waiver | Income; 200% FPL | Yes | Yes | 12/31/2017 |

| Mississippi | Waiver | Income; 199% FPL | Yes | Yes | 12/31/2017 |

| Missouri | Waiver | Income; 206% FPL | No | No (includes 18 year olds, but not younger teens) | 12/31/2017 |

| Montana | Waiver | Income; 216% FPL | No | No | 12/31/2017 |

| New Hampshire | SPA | Income; 201% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| New Mexico | SPA | Income; 255% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| New York | SPA | Income; 223% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| North Carolina | SPA | Income; 200% FPL | Yes | No | NA |

| Ohio | SPA | Income; 205% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Oklahoma | SPA | Income; 138% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Oregon | Waiver | Income; 250% FPL | Yes | Yes | 12/31/2016 |

| Pennsylvania | SPA | Income; 220% FPL | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Rhode Island | Waiver | Women losing Medicaid post-partum; no time limit | No | Yes | 12/31/2018 |

| South Carolina | SPA | Income; 199% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Virginia | SPA | Income; 205% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Washington | Waiver | Income; 250% FPL | Yes | Yes | 12/31/2016 |

| Wisconsin | SPA | Income; 306% FPL | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Wyoming | Waiver | Women losing Medicaid post-partum; no time limit | No | No | 12/31/2017 |

| NOTES: The Federal Poverty Level (FPL) is $11,770 for an individual in 2015. NA = Not applicable. *Currently being extended on month-to-month basis. SOURCE: Medicaid Family Planning Eligibility Expansions, State Policies in Brief, as of February 1, 2016, Guttmacher Institute. |

|||||

Appendix 4: Coverage Requirements for Medicaid Family Planning Services

| Appendix 4: Coverage Requirements for Medicaid Family Planning Services, by Type of Program | |||

| Coverage Requirement | |||

| Traditional Full-Scope Medicaid | Medicaid Family Planning Program | ACA Medicaid Expansion | |

|

FDA-approved prescription contraceptives:

|

State determined for each method | State determined for each method | Federally required for all FDA-approved methods |

| Sterilization for women | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

FDA-approved over the counter contraceptives:

|

State determined for each method | State determined for each method | State determined for each method without a prescription; federally required if prescribed |

| Contraceptive counseling | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

| STI and HIV counseling | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

| STI testing | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

| HIV testing | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

| HPV testing | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

| HPV vaccine | Federally required for beneficiaries ages 11-21; State determined for beneficiaries 22 and older | State determined for beneficiaries 22 and older | Federally required |

| Cervical cancer screening | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

| Breast cancer screening | State determined | State determined | Federally required |

Endnotes

Introduction

Guttmacher Institute. Public Funding for Family Planning, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2010, 2012.

Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (KCMU) and Urban Institute estimates based on data from FY 2011 Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS).

Ibid.

Issue Brief

Medicaid Family Planning Policy

Section 1905(a)(4)(C) of the Social Security Act.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Letter to State Medicaid Directors Re: Family Planning and Family Planning Related Services Clarification, April 16, 2014.

Kaiser Family Foundation and George Washington University Medical Center School of Public Health and Health Services, State Medicaid Coverage of Family Planning Services: Summary of State Survey Findings, 2009.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women, Committee Opinion: Access to Postpartum Sterilization, Obstetrics and Gynecology, July 2012.

Gavin, L., et al. Providing Quality Family Planning Services, MMWR, April 25, 2014.

Kaiser Family Foundation, Women and Health Care in the Early Years of the Affordable Care Act: Key Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey, May 2014.

Section 1903(a)(5) of the Social Security Act.

Guttmacher Institute. Public Funding for Family Planning, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2010, 2012.

RTI International. Title X Family Planning Annual Report, November 2012.

Guttmacher Institute. Public Funding for Family Planning, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2010, 2012.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Women and Health Care in the Early Years of the Affordable Care Act: Key Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey, May 2014.

KCMU and Urban Institute estimates based on data from FY 2011 MSIS.

Sections 1902(a)(23) and 1915(b) of the Social Security Act.

KCMU and Urban Institute estimates based on data from FY 2011 MSIS.

National Academy for State Health Policy, State Health Policy Monitor: Demonstration Waiver Programs, November 2008.

Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. Cost Benefit Analysis of the California Family PACT Program for Calendar Year 2007, April 2010.

Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. Cost Benefits from the Provision of Specific Methods of Contraception in 2009, April 2012.

Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. Family PACT Program Report, FY 2011-2012, 2013.

Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health. Cost Benefits from the Provision of Specific Methods of Contraception, April 2012.

The ACA, Medicaid Expansion, and Family Planning

KCMU. “A Closer Look at the Impact of State Decisions Not to Expand Medicaid on Coverage for Uninsured Adults.” April 2014.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis based on KCMU issue brief, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that do not Expand Medicaid – An Update.” January 2016.

KCMU. “A Closer Look at the Impact of State Decisions Not to Expand Medicaid on Coverage for Uninsured Adults.” April 2014.

Ricketts, S., Klingler, G., Schwalberg, R. Game change in Colorado: Widespread use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives and Rapid Decline in Births Among Young, Low-income Women, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, September 2014; 46(3).

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Unintended Pregnancy.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Women and Health Insurance, November 2013.

White, K., et al. Cutting Family Planning in Texas, NEJM. 2012; 367: 1179-1181.

Ibid.

Future Challenges

Kaiser Family Foundation. Coverage of Preventive Services for Adults in Medicaid, November 2014.

Food and Drug Administration Office of Women’s Health. Birth Control Guide.

California Legislative Information, Senate Bill No. 1053, Health Care Coverage: Contraceptives.

Guttmacher Institute. Variation in Service Delivery Practices Among Clinics Providing Publicly Funded Family Planning Services in 2010, 2012.

Decker, S. “In 2011, Nearly One-third of Physicians Said they Would not Accept New Medicaid Patients, but Rising Fees May Help,” Health Affairs, August 2012.

KCMU. How Much will Medicaid Physician Fees for Primary Care Rise in 2013, 2012.

Gemmill, A. Short Interpregnancy Intervals in the United States, Obstetrics and Gynecology, July 2013.

Tocce K, et al. Long Acting Reversible Contraception in Postpartum Adolescents: Early Initiation of Etonogestrel Implant is Superior to IUDs in the Outpatient Setting, J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. Feb 2012; 25(1):59-63.

“Health Policy Brief: The 340B Drug Discount Program,” Health Affairs, November 17, 2014.

Sommers BD, Rosenbaum S. Issues in Health Reform: How Changes in Eligibility may Move Millions Back and Forth Between Medicaid and Insurance Exchanges, Health Affairs. 2011;30(2):228–36.

Coleman, K., et al. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the New Millennium. Health Affairs. 2009; 28(1): 75-85.

Gavin, L., et al. Providing Quality Family Planning Services, MMWR, April 25, 2014; 63(4).

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMCS Maternal and Infant Health Initiative, July 17, 2014.