Contraceptive Coverage at the Supreme Court Zubik v. Burwell: Does the Law Accommodate or Burden Nonprofits’ Religious Beliefs?

Among the most contentious and litigated elements of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the requirement that most private health insurance plans provide coverage for a broad range of preventive services, including Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved prescription contraceptives and services for women. Since the implementation of the ACA contraceptive coverage requirement in 2012, over 200 corporations have filed lawsuits claiming that their religious beliefs are violated by the inclusion of that coverage or the “accommodation” offered by the federal government. The legal challenges have fallen into two groups: those filed by for-profit corporations and those filed by nonprofit organizations and both have reached the Supreme Court.

In the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision, the Supreme Court ruled that “closely held” for-profit corporations may be exempted from the requirement. This ruling, however, only settled part of the legal questions raised by the contraceptive coverage requirement, as other legal challenges have been brought by nonprofit corporations. The nonprofits are seeking an “exemption” from the rule, meaning their workers would not have coverage for some or all contraceptives, rather than an “accommodation,” which entitles their workers to full contraceptive coverage but releases the employer from paying for it.

The lawsuits brought by nonprofits have worked their way through the federal courts. On March 23, 2016, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument for Zubik v. Burwell, a consolidated case for seven legal challenges that involve nonprofit corporations. After the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, this already complicated case has taken on yet an additional question. Given that the Court will be operating with only 8 Justices, what would be the impact of a tie (4-4) decision? This brief explains the legal issues raised by the nonprofit litigation, discusses the influence of the Hobby Lobby decision on the current case before the Supreme Court, and the potential impact of a tie decision.

Who are the Petitioners in the Case Before the Supreme Court?

Since the contraceptive coverage regulations have been implemented, over 100 nonprofit corporations have challenged the contraceptive coverage requirement claiming that the accommodation for religiously affiliated nonprofits is insufficient and still burdens their religious rights. Multiple federal courts of appeals denied stays to all of the nonprofits involved in the litigation, finding that the accommodation is not a substantial burden. Only one federal Court of Appeals, the 8th Circuit, has ruled in favor of nonprofits, striking down the accommodation, but these nonprofits are not part of the case before the Supreme Court. Following these rulings, a number of the litigants petitioned the Supreme Court to review their cases, which the Court agreed to do on November 6, 2015. The named petitioners in the cases to be reviewed by the Court are: Zubik (the Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh), Priests for Life, Roman Catholic Archbishop, East Texas Baptist University, Little Sisters of the Poor, Southern Nazarene University, and Geneva College.1 All of the petitioners contend that complying with the accommodation triggers the contraceptive coverage, but the petitioners outline different burdens for fully insured plans, self-insured plans, and church plans (Appendix 1).

What is the Basis for the Challenges Brought by the Religious Nonprofits?

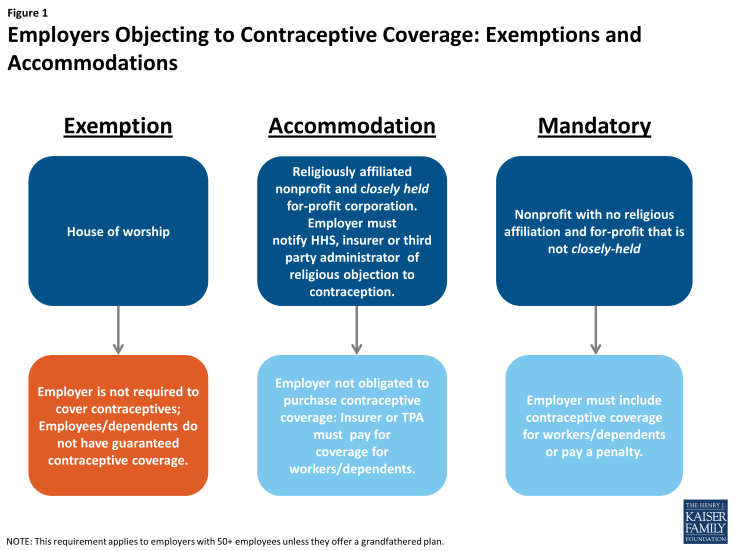

As the contraceptive coverage rules have evolved through litigation and new regulations, there are three categories of employers with differing requirements. Most employers are required to include the coverage in their plans. Houses of worship can choose to be exempt from the requirement if they have religious objections (Figure 1). Workers and dependents of exempt employers do not have coverage for either some or all FDA approved contraceptive methods. Religiously-affiliated nonprofits and closely held for-profit corporations are not eligible for an exemption. They can opt out of providing contraceptive coverage by notifying their insurer, third party administrator or the federal government of their objection and receive an accommodation which assures that their workers and dependents have contraceptive coverage, and relieves the employers of the requirement to pay for it.

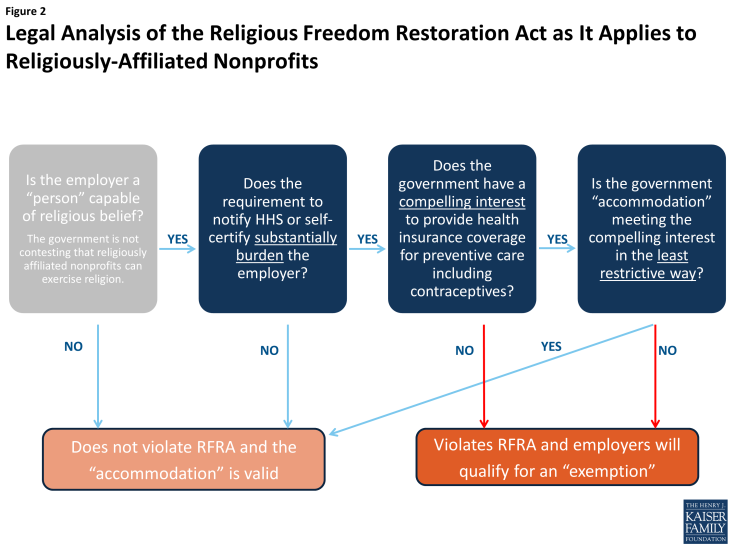

The nonprofit corporations continuing to pursue legal challenges are seeking an “exemption” from the contraceptive coverage rule, not an “accommodation.” They contend that they are unjustly burdened under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). RFRA was enacted in 1993 to protect “persons” from generally applicable laws that burden their free exercise of religion. The Government contends that it is federal law that requires the insurance issuer or the third party administrator to provide this coverage. In resolving these cases, the Court must consider a series of threshold questions in deciding whether the contraceptive coverage requirement is in violation of the RFRA (Figure 2). While RFRA was the basis for both the for-profit and nonprofit challenges, the questions raised by the Zubik consolidated cases differ somewhat. The nonprofit legal challenges involve a different question than the one raised by the for-profit challenges: Does the requirement to notify the employer’s insurer/TPA/government of their religious objection to contraceptive that results in an “accommodation” to the contraceptive coverage rule “substantially burden” the nonprofits’ religious exercise?

Figure 2: Legal Analysis of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act as it Applies to Religiously-Affliated Nonprofits

Do the Nonprofits Have a Sincerely Held Religious Belief?

The government is not contesting that the religiously affiliated nonprofits are considered “persons” under RFRA and hold sincerely held religious beliefs opposed to contraceptives.

Is the Accommodation a “Substantial Burden”?

The nonprofits must demonstrate the accommodation is a “substantial burden.” In other words, does the notice requirement that results in an “accommodation” to the contraceptive coverage requirement “substantially burden” the nonprofits’ religious exercise? Federal regulations require that religiously affiliated nonprofits with an objection to contraception either notify their insurer, third party administrator or Health and Human Services of their objection to including some or all contraceptives in their health insurance plan. This notice then qualifies them for an “accommodation” relieving them of the requirement to pay for the benefit, yet assuring that women workers and women dependents get the contraceptive coverage to which they are entitled under the ACA. The religiously-affiliated nonprofit organizations contend that when the insurer separately contracts with an employer’s workers to cover contraception at no cost, it remains part of the employer’s plan and is financed by the employer. By providing notice they contend they will “facilitate” or “trigger” the provision of insurance coverage for contraceptive services, enabling their insurance company or their third party administrator “to provide the morally objectionable coverage and allow their health plans to be used as a vehicle to bring about a morally objectionable wrong.”2 The Government contends that it is federal law that requires the insurance issuer or the third party administrator to provide this coverage, not the actual act of notification.

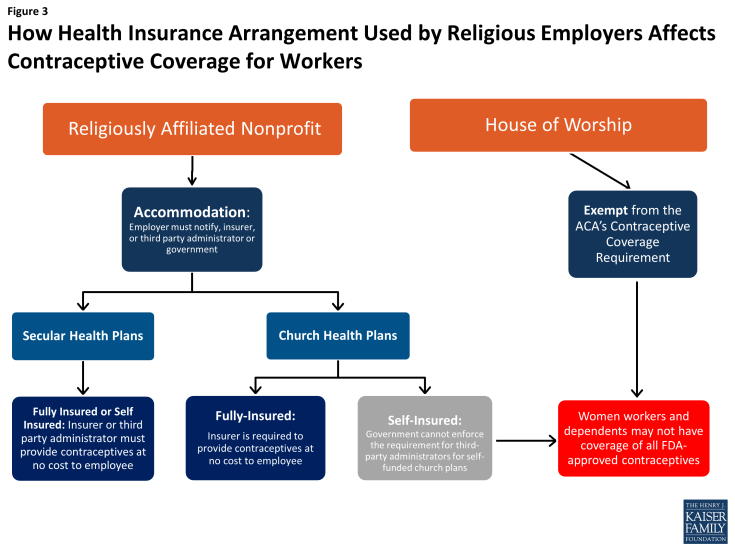

Religiously affiliated nonprofit employers offering a health insurance plan to their workers may choose whether to offer a fully insured plan, self-insured plan, or a church plan. The nonprofit employers challenging the accommodation have selected different types of health insurance plans that address the accommodation in different ways (Table 1).

| Table 1: Typology of Insurance Arrangements used by Litigants in the Zubik v. Burwell Consolidated Cases | |||

| Type of plan | How is the Accommodation is Handled | Payment for Coverage | Oversight |

| Fully-Insured Plan

Insurer collects premiums and assumes the risk of providing covered services |

The insurer must exclude contraceptive coverage from the employer’s plan3 and not apply any of the employer’s premium contributions to pay for the coverage.4 | No payment – federal government determined this coverage is cost neutral. | State insurance regulators |

| Self-Insured ERISA plan

Employer assumes the risk of providing covered services and usually contracts with a third party administrator (TPA) to manage the claims payment process. |

The TPA must provide contraceptive coverage to employees and dependents. The employer does not pay for or control this benefit but it is considered part of the employer’s plan. | The costs of the benefit are offset by reductions in the fees the TPA paid to participate in the federal exchange. The value is equal to the amount the TPA spent on contraceptive coverage plus a minimum 10% administrative fee.5 | Department of Labor under the Employer Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). |

| Self-Insured Church Plan

“A plan established and maintained for its employees (or their beneficiaries) by a church or by a convention or association of churches” and may also include entities controlled by or associated with a religious denomination.6 |

A TPA for a church plan is not required to provide the coverage. It can voluntarily choose to provide contraceptive coverage for the workers and dependents of an employer that has filed notice for an accommodation. | The costs of the benefit are offset by reductions in the fees the TPA paid to participate in the federal exchange. The value is equal to the amount the TPA spent on contraceptive coverage plus a minimum 10% administrative fee.5 | Unlike other fully-insured or self-insured plans, Church plans are not regulated by ERISA or state insurance agencies. There is effectively no enforcement authority for self-insured church plan TPAs to provide contraceptive coverage. |

One of the more complicated aspects of the cases relates to self-insured church plans because there are regulatory gaps in oversight of these particular entities when it comes to contraceptive coverage. Eighteen petitioners, including Little Sisters of the Poor, have a self-insured church plan,7 which is different than other types of employer self-insured plans in that it is explicitly not regulated by ERISA as are other self-insured plans. A church plan is a plan “established and maintained for its employees (or their beneficiaries) by a church or by a convention or association of churches.” Church plans are not limited to traditional church entities, but may include entities controlled by or associated with a religious denomination. For example, church-related hospitals, educational institutions and nonprofits that provide services to the aging, children, youth and family, may sponsor church plans. Because church plans are not governed under ERISA, they are not required to follow the ACA-related health reform mandates incorporated only into the ERISA law.8 However, church plans are required to follow all the ACA provisions included in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC).9 The IRS may impose penalty taxes on group health plans, including church plans for noncompliance with the contraceptive coverage provision.10

Employers with self-insured plans must designate entities to take on two different roles: plan administrator (who operates the plan) and third party administrator (who processes the claims). 11 These are typically two separate entities. However, when a religiously affiliated nonprofit employer with a self-insured plan provides notice of its objection to contraception, the contraceptive coverage regulations designate the plan TPA to function as the plan administrator, as defined in ERISA, but only for the contraceptive coverage benefit which effectively becomes a contraceptive plan.

Because the government’s authority to require a TPA to provide contraceptive coverage derives from ERISA, the government cannot actually enforce these regulations for self-funded church plans.12 While employers with self-funded church plans are required to provide notice of their objection, the TPAs for these plans have no enforceable obligation to provide the employees with contraceptive coverage. The litigants, however, contend that if a TPA voluntarily decides to offer the contraceptive services to the employees, the employer believes that they would be substantially burdened by the notice requirement (Figure 3).

Figure 3: How Health Insurance Arrangement Used by Religious Employers Affects Contraceptive Coverage for Workers

The parties’ arguments on this point are a bit circular. The Little Sisters of the Poor and others contend the Government cannot have a “compelling” reason to require them to complete the notice when their TPA is not required to provide the contraceptive coverage. In response, the Government asserts that because the employees will only receive contraceptive coverage if the TPAs for self-insured church plans voluntarily choose to provide the coverage, these nonprofits have an even more attenuated burden than other nonprofits and cannot claim that the notification “triggers” the coverage.13

Does the Contraceptive Coverage Requirement Further a Compelling Interest?

If the nonprofit corporations can show that they are substantially burdened, then the government will then need to prove that the contraceptive coverage requirement is a “compelling interest” that is met in the “least restrictive means.” The Government has articulated the same compelling reasons for the contraceptive coverage requirement in these cases as it did in Hobby Lobby. These reasons include: 1) safeguarding the public health, 2) promoting a woman’s compelling interest in autonomy and 3) promoting gender equality.14

In the Hobby Lobby decision, the Supreme Court did not adjudicate this issue; for the purpose of the ruling, they assumed that the Government had a compelling interest, and skipped to their analysis on whether the contraceptive mandate is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.”15 The Court may have skipped this question because there was no clear agreement among the five Justices signing onto the Court’s majority opinion on whether the Government had a compelling interest. In the decision, Justice Alito articulated that in order to demonstrate a compelling interest, the Government not only needs to show a compelling reason for the contraceptive coverage requirement generally, but the Government needs to specifically demonstrate “the marginal interest in enforcing the contraceptive mandate in these cases.”16 However, Justice Kennedy (who sided with the majority), and the four Justices that signed onto the dissent endorsed the position that providing contraceptive coverage to employees “serves the Government’s compelling interest in providing insurance coverage that is necessary to protect the health of female employees, coverage that is significantly more costly than for a male employee.”17

In these cases, the Government is also asserting a compelling interest in its ability to fill the gaps created by accommodations for religious objectors.18 The contraceptive coverage regulations, including the religious accommodations, also advance the government’s related compelling interest in assuring that women have equal access to recommended health care services.

In their briefs, the nonprofits contend that the government cannot have a compelling interest when it does not apply this requirement equally to all employers, effectively exempting those with less than fifty employees that do not provide health insurance, grandfathered plans, and houses of worship. Furthermore, grandfathered plans are required “to comply with a subset of the Affordable Care Act’s health reform provisions” that provide what HHS has described as “particularly significant protections.”19 But the contraceptive mandate is expressly excluded from this subset. “Here, granting a religious exemption for Petitioners would not undercut any “compelling” interest because the mandate is already riddled with exemptions.”20 Citing examples of other laws including the Civil Rights Act which allow exceptions, the Government counters that the exceptions to the contraceptive coverage requirement do not negate the Government’s compelling interest.21

IF the Government Demonstrates it Has a Compelling Interest, is it Meeting it in the “Least Restrictive Means”?

Lastly, the government must show it is meeting the compelling interest in the least restrictive means. The nonprofits argue there are less restrictive ways to accomplish the same goals, including allowing employees to qualify for subsidies on the exchange so they can enroll in an entirely new plan or a contraceptive only plan, or using Title X, the federal family planning program, to provide contraceptives to employees and dependents who lack coverage. The Government contends that none of these alternatives would be as effective in achieving its compelling interest because they would place “financial, logistical, informational, and administrative burdens” on women seeking contraceptive services.22

In the Court’s Hobby Lobby ruling, Justice Alito, wrote about the accommodation as a “less restrictive means,” to provide contraceptive coverage. The Court, however, did not decide whether the accommodation is lawful: “We do not decide today whether an approach of this type complies with RFRA for purposes of all religious claims. At a minimum, however, it does not impinge on the plaintiffs’ religious belief that providing insurance coverage for the contraceptives at issue here violates their religion, and it serves HHS’s stated interests equally well.”23

The majority opinion hints that the accommodation may not be least restrictive means: “The most straightforward way of doing this would be for the Government to assume the cost of providing the four contraceptives at issue to any women who are unable to obtain them under their health-insurance policies due to their employers’ religious objections. This would certainly be less restrictive of the plaintiffs’ religious liberty, and HHS has not shown … that this is not a viable alternative.”24 Justice Ginsburg disagrees with this position in her dissent citing evidence that Title X cannot absorb more people, and it would be burdensome for women to find out about and sign up for another health insurance plan for contraceptives.

Why Are Houses of Worship Suing if They Are “Exempt”?

Three houses of worship that are exempt from the contraceptive coverage rule are also petitioners in the cases before the Supreme Court. The Archdiocese of Washington, the Diocese of Pittsburg, and the Diocese of Erie, each sponsor a self-insured church plan administered by a TPA, and have invited nonexempt nonprofit religiously affiliated organizations to participate in their plan. The Dioceses which sponsor these plans can choose to either drop coverage for their affiliates or complete the accommodation form for the other employers participating in the church plan. The Diocese objects to “facilitating” contraceptive coverage for the workers and dependents, employed by the other participating nonprofits.

What Are Potential Ramifications of the Decision?

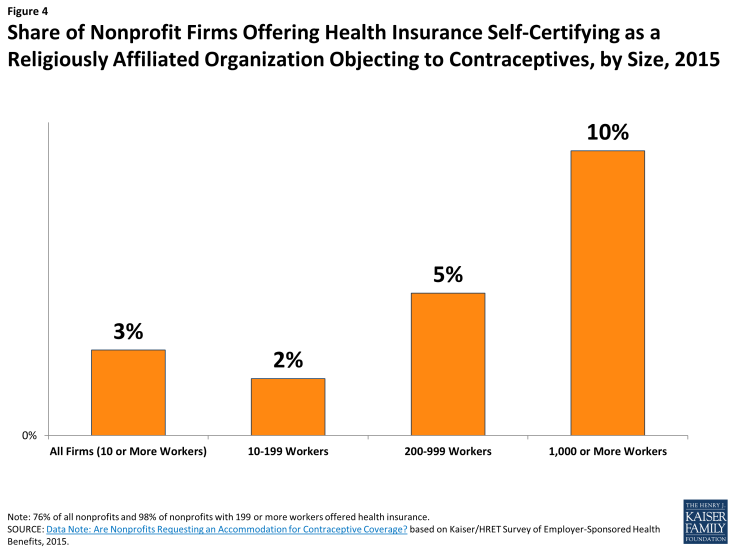

There is much at stake in the Court’s ruling on these cases. If the Court decides that the accommodation violates RFRA, then many workers and dependents may not receive contraceptive coverage because their employers will be exempt. Overall 3% of nonprofits offering health benefits (with 10 or more workers) have given notice for an accommodation, and a much larger share, 10% of nonprofits with 1,000 or more workers, have given notice for accommodation (Figure 4).25 It is not known if the nonprofits that have already filed notice of their objection and have obtained an accommodation would continue or would seek an exemption if that became an option.

Figure 4: Share of Nonprofit Firms Offering Health Insurance Self-Certifying as a Religiously Affiliated Organization Objecting to Contraceptives, by Size, 2015

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the religiously affiliated nonprofits, religious objectors in other contexts may be allowed to block the conduct of the government or third parties to fill in the gap left by the objector. The 10th Circuit court found that “Many religious objection schemes require an affirmative opt out before another person is required to step in and assume responsibility, and may require the objector to identify a replacement in the process.” 26 Lower courts have noted that if providing notice of an objection is a “substantial burden” then many other notifications resulting in opt outs could be affected including conscientious objector. “A religious conscientious objector to a military draft” could claim that being required to claim conscientious-objector status constitutes a substantial burden on his exercise of religion because it would “trigger the draft of a fellow selective service registrant in his place and thereby implicate the objector in facilitating war.”27

In his decision for the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals for Little Sisters v. Burwell,28 Judge Matheson notes other examples of when a religious objector is required to identify another person to step in: requiring a county clerk with objections to same sex marriage to designate someone else to solemnize a legal marriage;29 requiring pharmacists who object to providing contraception to refer patients to another pharmacist that will dispense the contraception;30 requiring health care providers who object to implementing a do-not-resuscitate order to “turn over care of the patient without delay to another provider who will implement the DNR order;”31 and requiring a church that opts out of paying Social Security and Medicare taxes for religious reasons to deduct those taxes from its employees’ paychecks as though the employees were self-employed.32

What Happens if There is a Split Decision?

In reviewing the seven nonprofit cases, the Supreme Court will have to decide whether the notice and the resulting accommodation from the contraceptive coverage requirement substantially burdens the religious exercise of nonprofits, whether the government has a compelling interest, and whether there is a less restrictive way of achieving the same of goal of allowing women coverage for all FDA-approved contraceptive methods without cost-sharing.

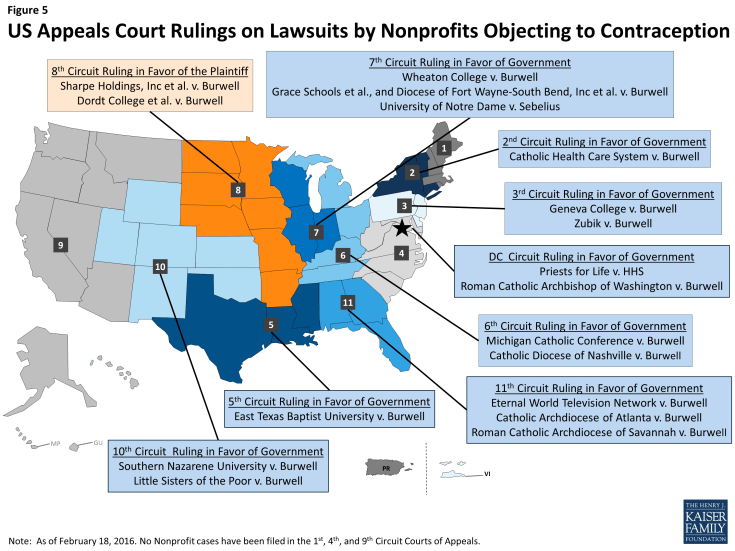

If the Court decision is a tie, 4-4, the rulings for each case heard by the lower courts of the U.S. District Courts of Appeals will stand. All of the Circuits that have heard the cases of the petitioners in the consolidated case have ruled in favor of the Government, finding that the accommodation is not a substantial burden. However, unlike the other Federal Courts of Appeals, the 8th Circuit ruled in two separate cases (Sharpe Holdings Inc. et al. v. Burwell, and Dordt College et al. v. Burwell) that the religiously affiliated nonprofits are substantially burdened by the accommodation to the contraceptive coverage requirement, and the accommodation is not the least restrictive means of furthering the government’s interests (Figure 5). These two cases, however, are not among the nonprofit employers petitioning the Supreme Court. So while a 4-4 decision by the Supreme Court would mean that all of the nonprofits before the court would need to abide by the accommodation, it would not be upheld and enforceable in the 8th Circuit (ND, SD, NE, MN, IA, MO, AR), meaning that the religiously affiliated nonprofits that object to contraception in those states would effectively become exempt from the requirement and their employees and dependents would not get contraceptive coverage. Alternatively, if the Court determines that that the Justices are split evenly, the Court might defer a decision and order a re-argument in the next term when there are nine Justices. The possibility also exists, if the Court issues a 4-4 decision, that it may revisit this issue in a future term when there are nine Justices to review the case.

Are These Supreme Court Cases The Final Word?

In addition to the current nonprofit cases that are being considered by the Court, there is other litigation by both employers and employees of organizations that are challenging the contraception coverage provisions. On August 31, 2015, the DC District Court issued a decision in a case brought by March for Life, and two of its employees. March for Life was formed after the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, and claims moral objections to many forms of contraceptives. As a secular nonprofit, however, it is not eligible for the exemption or accommodation available to religious organizations. This case represents a new legal approach and, for the first time, includes employees. The employer’s claim is that that the government has violated equal protection under the 5th Amendment by treating secular organizations with moral objections differently from religious organizations with religious objections. In addition, two employees of March for Life are also challenging the contraceptive coverage requirement under RFRA claiming they personally have religious objections to contraceptives, and do not want contraceptive coverage included in their plan. U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued a decision favorable to both March for Life and the two employees. The Administration has appealed this decision to the DC Court of Appeals; the court is holding the case until the Supreme Court issues a decision in Zubik v. Burwell.

More litigation may also emerge from for-profit employers like Hobby Lobby who also receive an accommodation from the requirements. Beginning in their new plan year,33 Hobby Lobby and other similar corporations will be required to notify their insurer or HHS of their objection to contraceptive coverage so that the insurer can still provide the contraceptive coverage directly to the employees and their dependents. Depending on the outcome of the nonprofit cases before the Supreme Court, some closely held corporations may challenge the accommodation as applied to them, contending that the accommodation still substantially burdens the corporation, in much the same way that the religiously-affiliated nonprofits have done.

The outcome of all of these cases will determine if the employees and dependents of these corporations, and potentially other firms that are eligible for the accommodation, will have access to no cost contraceptive coverage as intended under the ACA. As with most cases before the Supreme Court, the ruling will also likely have implications that go far beyond the issue of contraceptive coverage.