Abstinence Education Programs: Definition, Funding, and Impact on Teen Sexual Behavior

Teen sexual health outcomes over the past decade have been mixed. On one hand, teen pregnancy and birth rates have fallen dramatically, reaching record lows. On the other hand, rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among teens and young adults have been on the rise. Many schools and community groups have adopted programming that incorporates abstinence from sexual activity as an approach to reduce teen pregnancy and STI rates. The content of these programs, however, can vary considerably, from those that stress abstinence as the only option for youth, to those that address abstinence along with medically accurate information about safer sexual practices including the use of contraceptives and condoms. Early action from the Trump administration has signaled renewed support for abstinence-only programming. This fact sheet reviews the types of sex education models and state policies surrounding them, the major sources of federal funding for both abstinence and safer sex education, and summarizes the research on impact of these programs on teen sexual behavior.

Sex Education Models and State Policies

| Text Box 1: State-Level Sex Education Policy |

SOURCE: Guttmacher Institute. Sex and HIV Education. State Laws and Policies, as of May 1, 2018. |

Fact sheet examines abstinence education programs, funding and impact on teen sexual behavior

There are two main approaches towards sex education: abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education (Table 1). These categories are broad, and the content, methods, and targeted populations can vary widely between programs within each model. In general, abstinence-only programs, also known as “sexual risk avoidance programs,” teach that abstinence from sex is the only morally acceptable option for youth, and the only safe and effective way to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs. They generally do not discuss contraceptive methods or condoms unless to emphasize their failure rates. Comprehensive sex education is more diversely defined. Most generally, these programs include medically accurate, evidence-based information about both contraception and abstinence, as well as condoms to prevent STI transmission. Some programs, known as “abstinence-plus,” stress abstinence as the best way to prevent pregnancy and STIs, but also include information on contraception and condoms. Other programs emphasize safe-sex practices and often include information about healthy relationships and lifestyles.

| Table 1: Types of Abstinence Education Programs |

| Abstinence-Only Education – Also called “Sexual Risk Avoidance.” Teaches that abstinence is the expected standard of behavior for teens. Usually excludes any information about the effectiveness of contraception or condoms to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs. Sometimes must adhere to the 8-point federal definition (Table 3). |

| Abstinence-“Plus” Education – Stresses abstinence, but also includes information on contraception and condoms. |

| Comprehensive Sex Education – Provides medically accurate age-appropriate information about abstinence, as well as safer sex practices including contraception and condoms as effective ways to reduce unintended pregnancy and STIs. Comprehensive programs also usually include information about healthy relationships, communication skills, and human development, among other topics. |

The type of sex education model used can vary by school district, and even by school. Some states have enacted laws that offer broad guidelines around sex education, though most have no requirement that sex education be taught at all. Only 24 states and DC require that sex education be taught in schools (Text Box 1). More often, states enact laws that dictate the type of information included in sex education if it is taught, leaving up to school districts, and sometimes the individual school, whether to require sex education and which curriculum to use.

Funding Streams for Abstinence Education

Although decisions regarding if and how sex education is taught are ultimately left to individual states and school districts, abstinence-only funding offered by the federal government since the early 1980s’ has served as a strong incentive to adopt this type of programming. Since then, abstinence education curricula have evolved and federal financial support has fluctuated with each administration, peaking in 2008 at the end of the Bush Administration and then dropping significantly under the Obama administration.

| Table 2: Current Federal Funding Streams for Sex Education |

| Title V Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage (AOUM), established 1996 – Created under the Welfare Reform Act and reauthorized as the State Abstinence Education Grant Program in 2010. All programs must adhere to the federal A-H definition, and states must match every four federal dollars with three state dollars. Information about contraceptives and condoms may not be provided unless to emphasize failure rates. |

| Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), established 2010 – Enacted under the ACA, PREP awards grants to state health departments, community groups, and tribal organizations to implement medically accurate, evidence-based, and age-appropriate sex education programs that teach abstinence, contraception, condom use, and adulthood preparation skills. States receive grants based on the number of young people (ages 10-19) in each state, and programs must target those at high risk. 44 states and DC received PREP funding in FY2017.1 |

| Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPPP), 2010 – 2018 – A five-year competitive grant program established in 2010 under the ACA that funds private and public entities who work to reduce and prevent teenage pregnancy through medically accurate and age-appropriate programs, especially in communities at high risk. TPPP supports program implementation and capacity building for grantees, as well as development and evaluation of new approaches to teen pregnancy prevention. There are currently 84 TPPP grantees. However, the Trump Administration has released a new funding announcement that focuses on programs that teach abstinence instead of comprehensive sex education. |

| Sexual-Risk Avoidance Education (SRAE), established 2012 – Formerly known as the Competitive Abstinence Education Program (CAE), the program “seeks to educate youth on how to voluntarily refrain from non-marital sexual activity and prevent other youth risk behaviors.” All information provided must be medically accurate and evidence-based. |

| Division of Adolescent and School Health (DASH), established 1988 – DASH provides funding to state education agencies and local school districts to increase access to sex education, as well as to reduce disparities through the provision of HIV and STI prevention to young men who have sex with men. DASH also supports surveillance on youth risk behaviors and school health policies and practice. |

Background (1981 – 2010)

Until 2010, there were three major federal programs dedicated to abstinence education: the Adolescent Family Life Act (AFLA), the Community-Based Abstinence Education program (CBAE), and the Title V Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage program (AOUM). The AFLA and CBAE programs both provided grants to states and community organizations to promote “chastity and self-discipline,” and teach abstinence as the only acceptable practice for youth. While these programs have since been eliminated and replaced by other sex education funding streams, the Title V AOUM program remains the largest source of federal funding for abstinence education today.

The Title V AOUM program was enacted under the Clinton Administration’s Welfare Reform Act in 1996 (Table 2). Title V funds are tied to an 8-point definition of abstinence education, also referred to as the “A-H definition” (Table 3). While not all eight points must be emphasized equally, AOUM programs cannot violate the intent of the A-H definition and may not discuss safer-sex practices or contraception except to emphasize their failure rates. States that accept Title V grant money must match every four federal dollars with three state dollars, and they distribute these funds through health departments to schools and community organizations. Every state, except California, has received funding from this program at some point, and currently half of states do.2

| Table 3: 8-point “A-H” Federal Statutory Definition of Abstinence Education (applies to Title V AOUM Programs) |

|

A. has as its exclusive purpose teaching the social, psychological, and health gains to be realized by abstaining from sexual activity

|

| B. teaches abstinence from sexual activity outside marriage as the expected standard for all school-age children |

| C. teaches that abstinence from sexual activity is the only certain way to avoid out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and other associated health problems |

| D. teaches that a mutually faithful monogamous relationship in the context of marriage is the expected standard of sexual activity |

| E. teaches that sexual activity outside of the context of marriage is likely to have harmful psychological and physical effects |

| F. teaches that bearing children out-of-wedlock is likely to have harmful consequences for the child, the child’s parents, and society |

| G. teaches young people how to reject sexual advances and how alcohol and drug use increase vulnerability to sexual advances |

| H. teaches the importance of attaining self-sufficiency before engaging in sexual activity |

| SOURCE: Section 510 (b) of Title V of the Social Security Act, P.L. 104–193 |

Current Abstinence Programs

Under the Obama Administration, there was a notable shift in abstinence education funding toward more evidence-based sex education initiatives. The current landscape of federal sex education programs is detailed in Table 2 and includes newer programs such as Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), the first federal funding stream to provide grants to states in support of evidence-based sex education that teach about both abstinence and contraception. In addition, the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPPP) was established to more narrowly focus on teen pregnancy prevention, providing grants to replicate evidence-based program models, as well as funding for implementation and rigorous evaluation of new and innovative models.

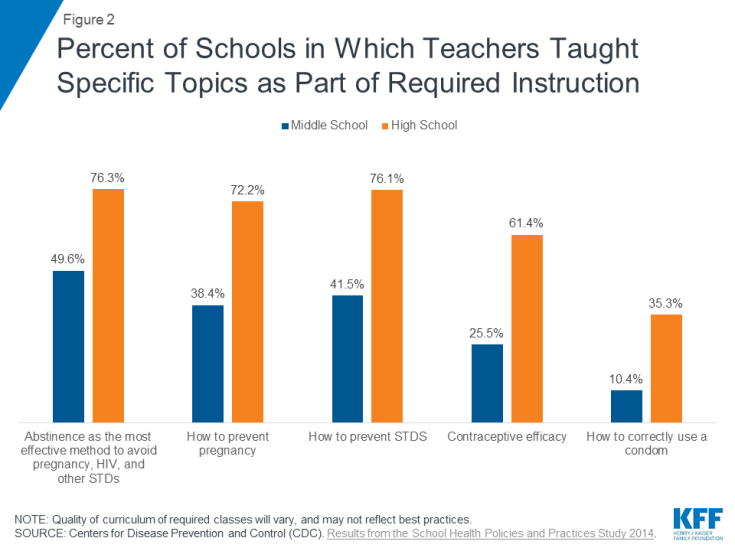

Nonetheless, support for abstinence education programs continues. Although Congress allowed the Title V AOUM program to expire in 2009, it was resurrected in the Affordable Care Act legislation signed by President Obama. In 2012, Congress also established the Competitive Abstinence Education grant program, now known as the Sexual Risk Avoidance Education program (SRAE). Initially tied to the A-H definition, it no longer has this requirement; however, the program still teaches youth to “voluntarily refrain from non-marital sexual activity and prevent other youth risk behaviors.” Federal funding for this program bypasses state authority by granting funds directly to community organizations. In 2017, federal funding for the Title V and SRAE programs totaled $90 million (Figure 1).

Figure 1: In 2017, One-Third of Federal Funding for Teen Sexual Health Education Programs Was For Abstinence Education

The Trump Administration’s early actions signal changes in sex education programming. The 2017 TPPP grant recipients received notice from Health and Human Services that their funding was ending on June 30, 2018, two years early, citing a lack of evidence of the program’s impact despite the fact that many of the grantees’ projects had not yet concluded. Nine organizations sued in Washington, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, arguing that their grants were wrongfully terminated. Federal judges in each of the four lawsuits ruled in favor of the organizations, allowing the programs to continue until the end of their grant cycle in 2020. At the same time, the Trump Administration announced the availability of new funding for the TPP program with updated guidelines. These new rules require grantees to replicate one of two abstinence programs—one that follows a sexual risk avoidance model, and one that follows a sexual risk reduction model– in order to receive funding. This marks a sharp departure from the rules under the Obama administration, which allowed grantees to choose from a list of 44 evidence-supported programs that vary by approach, target population, setting, length, and intended outcomes.3 Applications for the new grants are due at the end of June 2018.

In addition, Congress passed the 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which included a $10 million funding increase for abstinence-only SRAE grant program, bringing the total to $25 million – a 67% increase.4 In November 2017, HHS also announced a new $10 million research initiative in partnership with Mathematica Policy Research and RTI International to improve teen pregnancy prevention and sexual risk avoidance programs.5

Impact on Sexual Behavior and Outcomes Among Youth

Proponents of abstinence education argue that teaching abstinence to youth will delay teens’ first sexual encounter and will reduce the number of partners they have, leading to a reduction in rates of teen pregnancy and STIs.6 However, there is currently no strong body of evidence to support that abstinence-only programs have these effects on the sexual behavior of youth and some have documented negative impacts on pregnancy and birth rates.

In 2007, a nine-year congressionally mandated study that followed four of the programs during the implementation of the Title V AOUM program found that abstinence-only education had no effect on the sexual behavior of youth.7 Teens in abstinence-only education programs were no more likely to abstain from sex than teens that were not enrolled in these programs. Among those who did have sex, there was no difference in the mean age at first sexual encounter or the number of sexual partners between the two groups. The study also found that youth that participated in the programs were no more likely to engage in unprotected sex than youth who did not participate. While teens who participated in these programs could identify types of STIs at slightly higher rates than those who did not, program youth were less likely to correctly report that condoms are effective at preventing STIs. A more recent review also suggests that these programs are ineffective in delaying sexual initiation and influencing other sexual activity.8 Studies conducted in individual states found similar results.9,10 One study found that states with policies that require sex education to stress abstinence, have higher rates of teenage pregnancy and births, even after accounting for other factors such as socioeconomic status, education, and race.11

A study that found an abstinence-only intervention to be effective in delaying sexual activity within a two-year period received significant attention as the first major study to do so.12 While advocates of comprehensive sex education recognize the study as rigorous and credible, they argue that the programs in these studies are not representative of most abstinence-only programs. Instead, the evaluated programs differed from traditional abstinence-only programs in three major ways: they did not discuss the morality of a decision to have sex; they encouraged youth to wait until they were ready to have sex, rather than until marriage; and they did not criticize the use of condoms.13

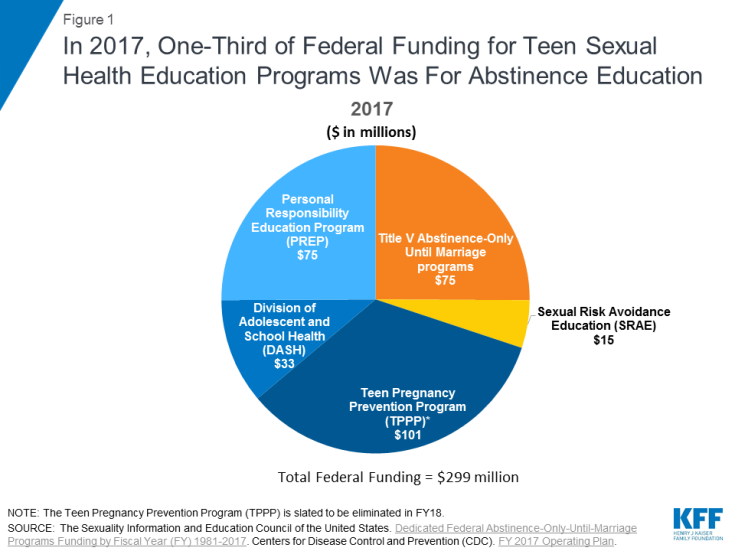

There is, however, considerable evidence that comprehensive sex education programs can be effective in delaying sexual initiation among teens, and increasing use of contraceptives, including condoms. One study found that youth who received information about contraceptives in their sex education programs were at 50% lower risk of teen pregnancy than those in abstinence-only programs.14 It also found that teens in these more comprehensive programs were no more likely than those receiving abstinence-only education to engage in sexual intercourse, as some critics argue. Another study found that over 40% of programs that addressed both abstinence and contraception delayed the initiation of sex and reduced the number of sexual partners, and more than 60% of the programs reduced the incidence of unprotected sex.15,16,17 Despite this growing evidence, in 2014, roughly three-fourths of high schools and half of middle schools taught abstinence as the most effective method to avoid pregnancy, HIV, and other STDs, just under two-thirds of high schools taught about the efficacy of contraceptives, and about one-third of high schools taught students how to correctly use a condom (Figure 2).

Conclusion

The Trump administration continues to shift the focus towards abstinence-only education, revamping the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program and increasing federal funding for sexual risk avoidance programs. Despite the large body of evidence suggesting that abstinence-only programs are ineffective at delaying sexual activity and reducing the number of sexual partners of teens, many states continue to seek funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs and mandate an emphasis on abstinence when sex education is taught in school. There will likely be continued debate about the effectiveness of these programs and ongoing attention to the level of federal investment in sex education programs that prioritize abstinence-only approaches over those that are more comprehensive and based on medical information.

Endnotes

Health and Human Services Administration (HHS). 2017 Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP) Awards.

SIECUS. A History of Federal Funding for Abstinence-Only Until Marriage Programs.

Office of Adolescent Health, HHS. Evidence-Based Teen Pregnancy Prevention Programs at a Glance.

HHS, Administration for Children and Families. HHS Announces New Efforts to Improve Teen Pregnancy Prevention & Sexual Risk Avoidance Programs. November 3, 2017.

Heritage Foundation (2010). Evidence on the Effectiveness of Abstinence Education: An Update.

Mathematica Policy Research (2007). Impacts of Four Title V, Section 510 Abstinence Education Programs.

Santelli JS, et al. Guttmacher Institute. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61 (2017) 273e280.

Hauser, D. Advocates for Youth. Five Years of Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Education: Assessing the Impact.

Stanger-Hall, K. F., & Hall, D. W. (2011). Abstinence-Only Education and Teen Pregnancy Rates: Why We Need Comprehensive Sex Education in the U.S. PLoS ONE, 6(10), e24658.

Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Efficacy of a Theory-Based Abstinence-Only Intervention Over 24 Months: A Randomized Controlled Trial With Young Adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(2):152–159.

Stein R. (2010, February 2). Abstinence-only programs might work, study says. Washington Post

Kohler, Pamela & Manhart, Lisa & E Lafferty, William. (2008). Abstinence-Only and Comprehensive Sex Education and the Initiation of Sexual Activity and Teen Pregnancy. The Journal of adolescent health. 42. 344-51.

Kirby, D.B. The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sex Res Soc Policy (2008) 5: 18.

S Denford et al. A Comprehensive Review of Reviews of School-Based Interventions to Improve Sexual-Health. Health Psychol Rev 11 (1), 33-52. 2016 Nov 07.

Chin, Helen B. et al. The Effectiveness of Group-Based Comprehensive Risk-Reduction and Abstinence Education Interventions to Prevent or Reduce the Risk of Adolescent Pregnancy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and Sexually Transmitted Infections. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 42, Issue 3, 272 – 294.