Women and Health Care in the Early Years of the ACA: Key Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women's Health Survey

Reproductive and Sexual Health Services

Reproductive and sexual health is an integral component of women’s general health and well-being. The ACA makes many reforms to insurance coverage that may improve access to these important services for insured women, in addition to broadening the availability of coverage to uninsured individuals. The ACA’s requirement for preventive services coverage without cost sharing includes a number of counseling services, screening tests, and supplies that could affect women’s access to reproductive and sexual health services, such as contraceptives, screening tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV, and the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine. They also include pregnancy-related services such as prenatal visits, folic acid supplements, screening tests, tobacco cessation, and breastfeeding supports. Notably, the law includes maternity care as an Essential Health Benefit category that all new health plans must cover in their policies.

The ACA’s large coverage expansion to the uninsured may also make changes in the types of settings that women, particularly those who are newly insured, will use to obtain their reproductive care. This change in coverage patterns may have a disproportionate effect on family planning clinics and community health centers, who have long served low-income women, but may not be part of the health care provider networks contracting with the Marketplace plans. The ACA’s extension of dependent coverage up to age 26 also extends a new coverage option to women at a peak time in their lives when they typically seek reproductive and sexual health care. The fact, however, that these adult children are part of their parents’ insurance during this period also raises questions about privacy and confidentiality around the services they use when the primary policy holders are their parents. This section reports survey findings among women of reproductive age, 15 to 44 years old.

Use of Services

Most reproductive age women have had a gynecologic or obstetric visit in the past year.

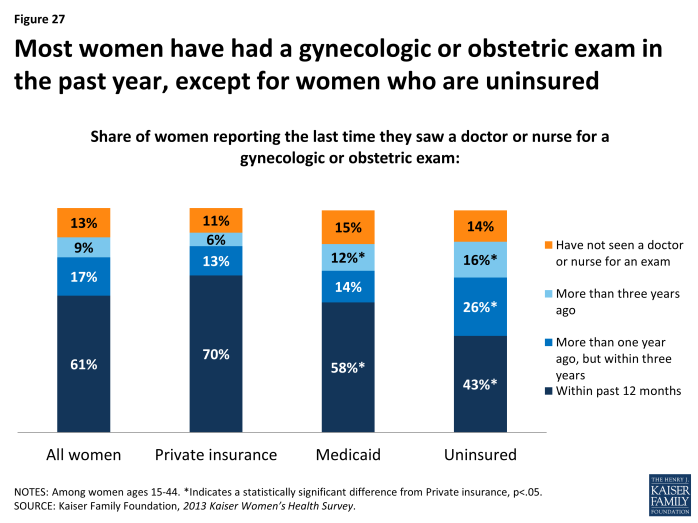

The majority of women ages 15 to 44 report that they have had a gynecologic or obstetric visit in the past year (61%). Women with private insurance, however, have higher rates of a recent visit (within the past 12 months) for obstetric or gynecologic care (70%), compared to women with Medicaid (58%) and uninsured women (43%). A higher share of women covered by Medicaid (12%) and uninsured women (16%) reported that their last visit was over three years ago, more than twice the rate of women with private insurance (6%) (Exhibit 6.1). Just 13% of women ages 15 to 44 reported that they have never seen a provider for obstetric or gynecologic care and the rates were similar for all the insurance groups.

Most women (85%) report that their most recent sexual health visit was for gynecologic care and 14% report it was for prenatal care (Table 7). Almost one in four Hispanic women report that the reason was for pregnancy related care (23%), higher than for White (13%) and Black women (9%). Slightly more women ages 25 to 34 reported their most recent visit was for prenatal or pregnancy-related care (17%), and the shares of younger (12%) and older women (11%) were similar.

| Table 7: Reason for most recent gynecologic visit, by age group, race/ethnicity, and poverty level | |||||||||

| All Women | Age Group | Race/Ethnicity | Poverty Level | ||||||

| 15-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | White | Black | Hispanic | Less than 200% FPL | 200% FPL or greater | ||

| Have had a gynecological or obstetric exam within the past year | 61% | 44% | 74%* | 64% | 62% | 70% | 56% | 56%* | 68% |

| Reason for most recent visit | |||||||||

| Gynecologic care | 85% | 85% | 82% | 87% | 86% | 90% | 75%* | 79%* | 90% |

| Prenatal/ Pregnancy Care | 14% | 12% | 17% | 11% | 13% | 9% | 23%* | 20%* | 9% |

| NOTE: Reason for most recent visit among women ages 15-44 who have ever had an obstetric or gynecologic exam. Federal Poverty Level was $19,530 for a family of three in 2013. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from ages 15-24; White; 200% FPL or greater; p<.05.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. | |||||||||

Private doctors’ offices and HMOs are the primary settings where women get gynecologic care, but family planning clinics and community health centers play a significant role for women who have Medicaid and women who are uninsured.

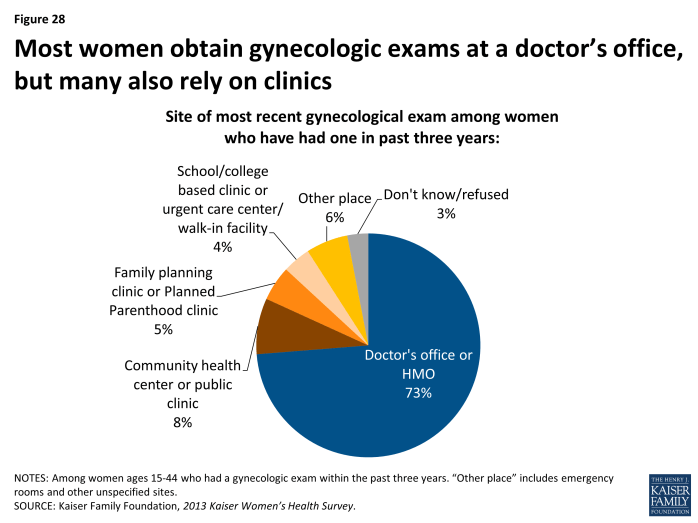

Among the group of women who said they have had a gynecologic exam (not for pregnancy related care) within the past three years, 73% report that their most recent exam was at a doctor’s office or HMO (Exhibit 6.2). Among women who have a had a gynecologic exam in the past three years, nearly one in ten women (8%) report their most recent exam was at a community health center or public clinic. Fewer younger women sought care at a doctor’s office or HMO (64%) than other women of reproductive age, with slightly more seeking care at school based clinics and urgent care centers/ walk-in facilities than other women (Table 8). Not surprisingly, health care settings vary for women with different types of insurance coverage.

| Table 8: Site of most recent gynecologic exam among women, by age and insurance coverage | |||||||

| All Women | Age Group | Insurance Coverage | |||||

| Site of most recent visit | 15-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | Private Insurance | Medicaid | Uninsured | |

| Doctor’s office or HMO | 73% | 64% | 72% | 82% | 84% | 57%* | 53%* |

| Community health center or public clinic | 8% | 9% | 8% | 7% | 4% | 13% | 16%* |

| Family planning clinic or Planned Parenthood | 5% | 6% | 5% | 4% | 2% | 5% | 16%* |

| School/college based clinic or urgent care center/ walk-in facility | 4% | 9% | 3% | 1% | 4% | 5% | 5% |

| Other place | 6% | 6% | 7% | 4% | 4% | 13% | 5% |

| Don’t know/refused | 4% | 3% | 5% | 2% | 1% | 7% | 3% |

| NOTE: Among women ages 15-44 who have had an exam in the past three years. Other place includes other types of clinics and other locations such as emergency departments. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from ages 35-44; Private Insurance; p<.05. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. |

|||||||

Women with private insurance overwhelmingly get their gynecologic care from private doctor’s offices or HMOs. While just over half of women enrolled in Medicaid and uninsured women obtain care from a doctor’s office/HMO, community health centers, family planning clinics and school based clinics play an important role for these groups. A larger portion of women covered by Medicaid (13%) seek care in another location, which includes emergency departments, compared to women with private insurance and uninsured women. A sizable share of private physicians limits their participation in Medicaid, and safety net providers play an important role serving low-income and uninsured women. As more women gain coverage under the ACA, especially through the subsidized private plans available on state Marketplaces, many of the women using these safety net providers could shift to private settings because their existing providers may not be in-network providers.

Counseling and Screening

Among reproductive health topics, counseling is more commonly reported for birth control than for other issues such as sexual history, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV.

An important aspect of reproductive and sexual health care is the counseling and education that health care clinicians can offer patients. Counseling allows clinicians to provide patient education, screen for high-risk behaviors, and identify the need for additional testing services. Providers can now be reimbursed when they provide counseling on a wide range of sexual health topics, because they are part of the preventive services that the ACA requires plans to cover without cost sharing. This is especially important because some of the health challenges women face during their reproductive years stem from sexual and reproductive health concerns. It is estimated that half of all pregnancies in the U.S. are unintended.1 The CDC estimates approximately 19 million new cases of STIs, such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HPV, occur each year.2 Approximately half of cases occur among young people ages 15 to 24, and disproportionately affect certain communities, with Black women at elevated risk for contracting an STI. Sex is also the major mode of transmission of HIV/AIDS among women, which has had a disproportionate impact on young women of color, particularly Black women.

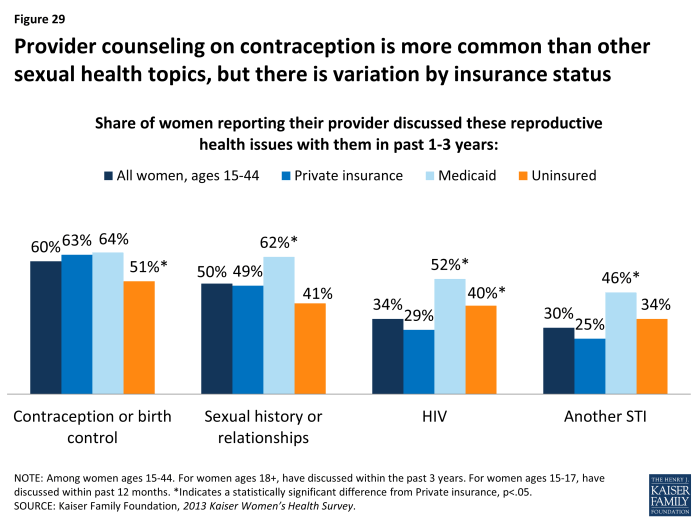

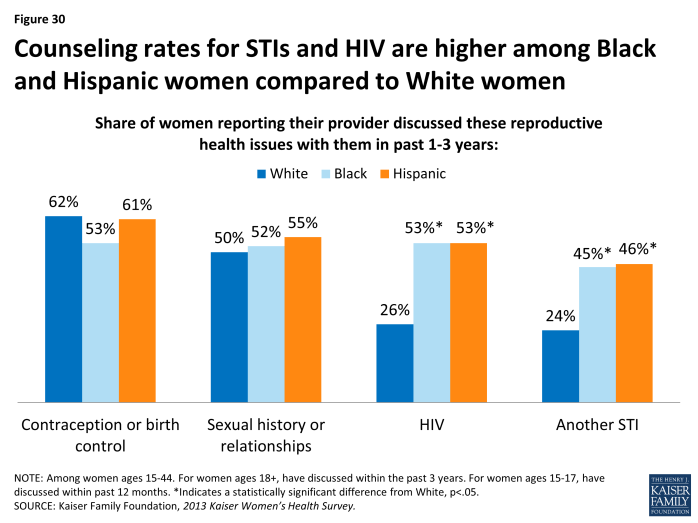

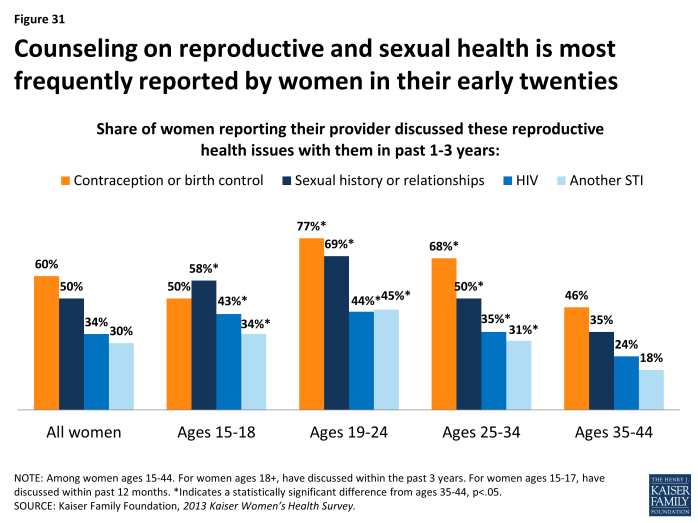

Despite the high rates of STIs and unintended pregnancy, and the recommendations of professional groups, counseling on many of these topics is not routine among women of reproductive age (Exhibit 6.3). While most reproductive age women have had recent conversations with a provider about contraception (60%), the rate is much lower for other topics, including sexual history (50%), HIV (34%) and other STIs (30%). It is notable that women with Medicaid have significantly higher rates of counseling on most of these topics compared to women with private insurance. Women of color also report higher rates of counseling on HIV and other STIs, compared to White women (Exhibit 6.4). Women ages 19 to24 also have the highest rate of counseling from a health care provider on these topics (Exhibit 6.5).

Despite the burden of sexual violence on women in the U.S., counseling on dating and domestic violence is particularly infrequent in a health setting.

More than 1 in 3 adult women in the United States (36%) have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.3 Intimate partner violence (IPV), also called domestic or dating violence, can affect women at any point in their lives, but rates are highest among women in their reproductive years.4 IPV can take many forms, including sexual violence, physical violence, and psychological and emotional abuse. It has long been recognized that clinicians can play an important role in the identification and treatment of women who have suffered from violence. As with other sexual and reproductive health topics, counseling on domestic violence is highly sensitive and requires training, including special protections for patients’ privacy, and knowledge of referrals so patients receive safe and effective follow up care and are protected from retaliation by perpetrators.

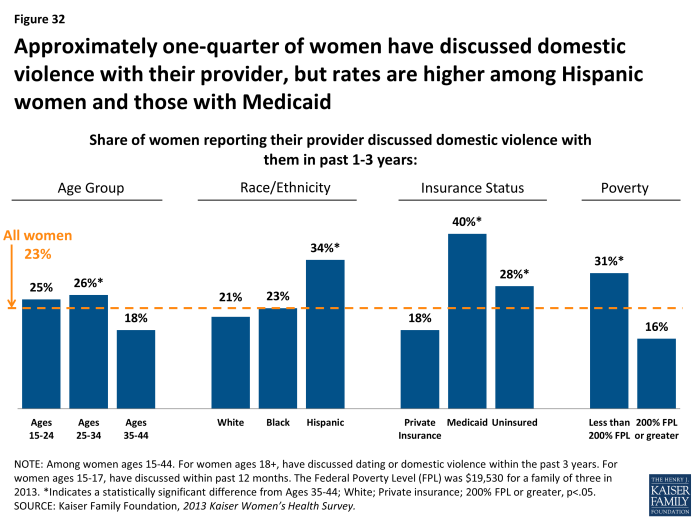

One of the preventive services for women that the ACA covers without cost sharing is provider counseling on IPV. While there have been advances in the health care system’s handling of IPV and newly developed screening tools for providers to use, it is still far from routine for providers to raise the issue of violence with women. Nearly one-quarter of women ages 15 to 44 (23%) have discussed dating or domestic violence with a provider in the past three years (Exhibit 6.6). Compared to older women, provider-patient conversations about IPV are more common among women in their twenties and early thirties, but it is still not the norm. Counseling rates for IPV are also higher among Hispanic women, those who are low-income, and those covered by Medicaid.

Approximately four in ten women report recent screenings for HIV and other STIs, but many incorrectly assume they are being tested.

Several professional groups and government agencies, including the USPSTF, the Institute of Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommend that women in their reproductive years be tested for sexually transmitted infections such as chlamydia, gonorrhea and HIV.5,6,7 Knowing one’s status is important to receive early treatment and prevent transmission to sexual partners. As with provider counseling, these tests are now covered without cost sharing in new private plans under the ACA’s preventive services coverage requirements. They are also commonly included as part of family planning services under Medicaid.8

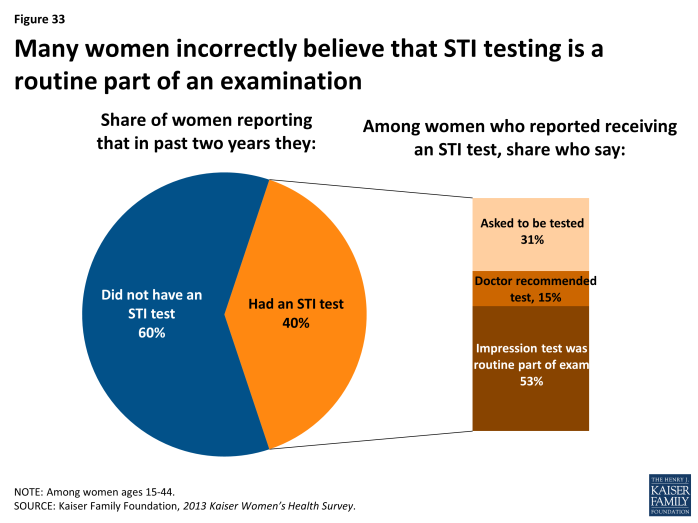

Approximately four in ten women report that they have had a test for HIV (44%) or other STIs (40%) in the past two years; however, approximately half of these women assumed this test was a routine part of an examination—which it is not (Exhibit 6.7). Therefore, the actual screening rate is likely lower than the share of women who report being tested. This perpetuates the gap in knowledge of HIV status and other STIs that has been reported in other research and may cause women to believe they do not have an STI when in fact they have not actually been tested.

Screening rates for HIV and STIs are higher among low-income, Medicaid, uninsured, and minority women, particularly Black women (Table 9). Notably, there is a higher rate among some of these groups of women reporting that they requested their provider to conduct these tests; however, among all these groups, a substantial share also still incorrectly assume the test is routinely included in a health exam.

| Table 9: Receipt of sexual health screening tests, by race/ethnicity, insurance status, poverty level | |||||||||

| All Women | Race/Ethnicity | Insurance Status | Poverty Level | ||||||

| Reported having test in past 2 years | White | Black | Hispanic | Private | Medicaid | Uninsured | Less than 200% FPL | 200% FPL or greater | |

| HIV Test | 44% | 35% | 72%* | 60%* | 37% | 59%* | 51%* | 54%* | 37% |

| Thought test was routine part of Exam | 56% | 60% | 48% | 53% | 56% | 46% | 61% | 56% | 55% |

| Doctor recommended test | 14% | 14% | 7% | 22% | 16% | 9% | 13% | 12% | 18% |

| Asked to be tested | 27% | 23% | 43%* | 24% | 27% | 41% | 22% | 30% | 26% |

| STI Test | 40% | 33% | 63%* | 50%* | 37% | 55%* | 38% | 47%* | 36% |

| Thought test was routine part of exam | 53% | 55% | 47% | 54% | 58% | 35% | 59% | 50% | 58% |

| Doctor recommended test | 15% | 11% | 18% | 21% | 14% | 15% | 13% | 14% | 14% |

| Asked to be tested | 31% | 32% | 35% | 23% | 28% | 47% | 27% | 35% | 27% |

| NOTE: Among women ages 15-44. Federal Poverty Level was $19,530 for a family of three in 2013. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from White; Private insurance; 200% FPL or greater; p<.05.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. | |||||||||

Use of Contraceptives

Nearly half of sexually active reproductive age women use at least one form of contraception, but approximately one in five sexually active women of reproductive age report that they do not use contraception despite reporting they do not want to get pregnant.

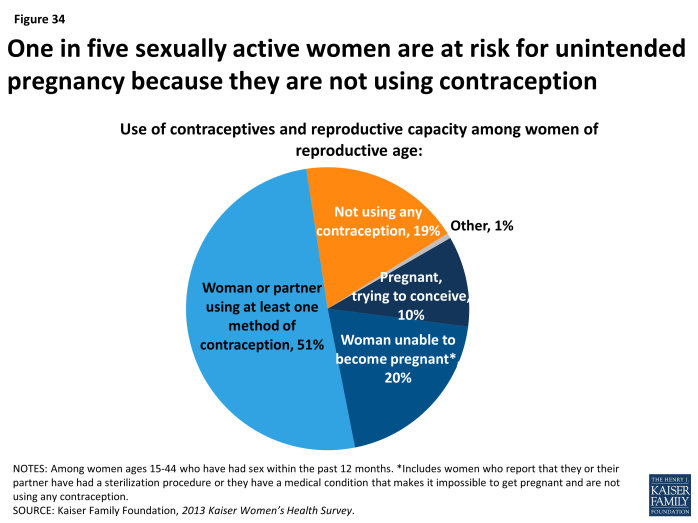

The vast majority of women who are of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) have been sexually active (81%) in the past year. Among sexually active women, one in ten are pregnant or trying to conceive, and one in five (20%) women report that they or their partners have had a sterilization procedure or cannot become pregnant. For women with reproductive capacity but who want to avoid an unintended pregnancy, contraception is an essential health service. Some contraceptives also can reduce the risk of transmitting certain STIs (such as condoms) and in some cases can assist in managing other medical conditions (such as oral contraceptives). Among reproductive age women who have had sex in the past year, half (51%) report that they or their partners used at least one contraceptive method (Exhibit 6.8). An estimated 19% of sexually active women ages 15 to 44 are at high risk for unintended pregnancy because they or their partners are not using contraception.

Condoms and birth control pills are the most commonly used forms of contraception.

While all forms of FDA approved contraception can reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy when used correctly, they vary in their use and effectiveness. Women are encouraged to consider a range of issues when choosing a contraceptive method in order to find the one that is most effective but also fits best within their beliefs and lifestyle. Condoms can protect against STIs and are widely available through many outlets without a prescription. Oral contraceptives, often referred to as the Pill, require prescriptions, are hormonal, and cannot be used or tolerated by all women. Other methods include injectables, implants, patches, and the vaginal ring, which deliver different doses of hormones. Intrauterine Devices (IUD) are devices that are inserted in a woman’s uterus by a provider and some types also include hormones. They can last up to 5 years or longer and are among the most effective methods of reversible contraception but also have the highest up front cost. Under the ACA’s preventive services provision, all new private plans are required to cover all FDA-approved methods of contraception as prescribed for women without cost sharing.

| Table 10: Types of contraceptives used among sexually active women, by age and race/ethnicity | |||||||

| All Women | Age Group | Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Types of contraception used within the past 12 months | 15-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | White | Black | Hispanic | |

| Male condoms | 63% | 82% | 60%* | 41% | 59% | 78%* | 59% |

| Oral contraceptives | 48% | 54% | 44% | 46% | 53% | 36%* | 49% |

| IUD | 19% | N/A | 29% | 22% | 24% | 10%* | 17% |

| Injectables | 7% | 13% | 6% | 1% | 3% | 16%* | 11% |

| Implants | 6% | N/A | 8%* | 1% | 6% | 8% | 8% |

| Other | 12% | 12% | 14% | 11% | 12% | 7% | 17% |

|

NOTES: Only includes women ages 15-44 who were sexually active in past year and used contraceptives in past year. Women may use more than one form of contraception. Oral contraceptives include birth control pills. IUD is an intrauterine device such as Mirena, Skyla, or Paragard. Injectables include Depo-Provera. Implants include Implanon or tubes in arm. Other methods include vaginal ring and the topical patch. N/A indicates data are not sufficient to meet criteria for statistical reliability. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from 35-44; White; p<.05.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey.

|

|||||||

Among sexually active women who use contraception, just over half (54%) rely on one method and just under half (45%) use more than one method. Women most frequently report that they have used condoms and birth control pills in the past year (Table 10). Nearly two-thirds (63%) of sexually active women who have used contraceptives in the past year report using male condoms, almost half have used birth control pills (48%), and about one in five (19%) use an IUD. Nearly one in four White women (24%) report that they are using an IUD. A larger share of Black women than White or Hispanic women use condoms. Black women also have higher usage of injectables than White or Hispanic women.

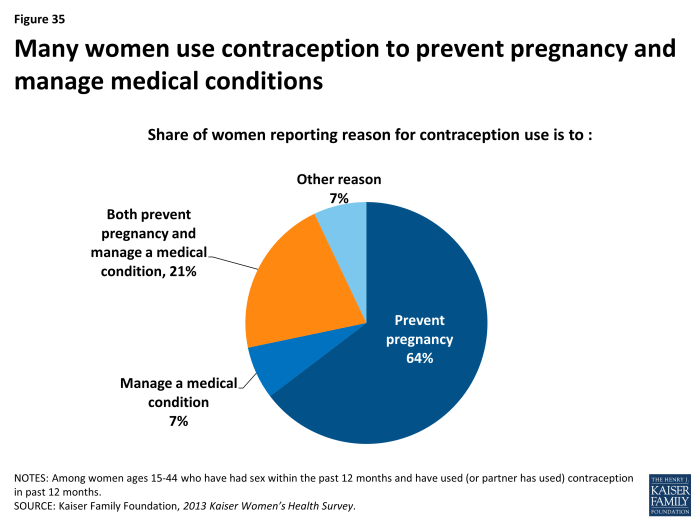

While preventing pregnancy is the leading reason for contraceptive use, a sizable fraction of women also use them to manage a medical condition.

While contraceptives are essential for preventing and spacing pregnancies, they can also aid in the management of a wide range of medical conditions such as endometriosis, irregular periods, and fibroids.9,10 Not surprisingly, preventing pregnancy is the main reason for using contraceptives (64%), but a fair share of women (21%) state they use it to prevent pregnancy and manage a medical condition (Exhibit 6.9). This factor likely affects women’s choices in the types of contraceptives they select.

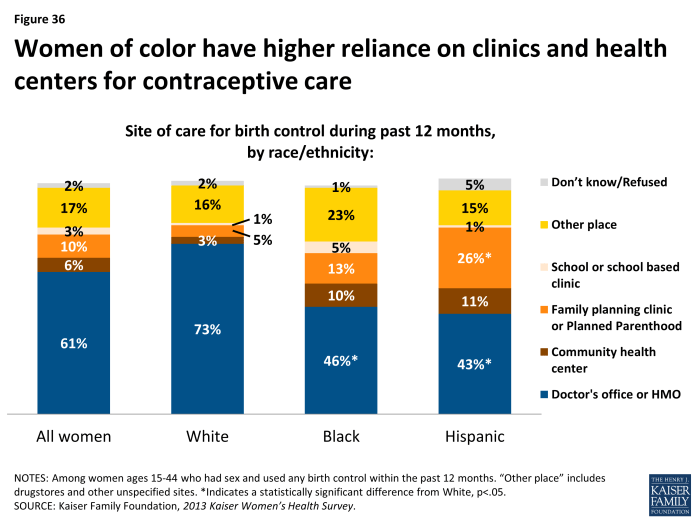

While most women get their contraceptives from a private physician or HMO, a significant minority get their contraceptives from a clinic-based provider.

Six in ten sexually active women who are using birth control report that they obtain contraceptives at a doctor’s office or HMO (61%), one in ten (10%) obtain it at a family planning clinic, such as Planned Parenthood, and 6% from a community health center (Exhibit 6.10). Higher shares of women of color go to clinics for contraceptives though. Nearly three-fourths of White women report they obtained contraceptive care at a doctor’s office or HMO, compared to less than half of Black (46%) and Hispanic (43%) women. Conversely, reliance on family planning clinics and community health centers is more than twice as high among women of color as for White women. This is the case for more than a third (37%) of Hispanic women, who also have the highest uninsured rate. Some of the differences in site of care are likely related to insurance status, which means that over time there could be changes in where women obtain care for contraceptives as the ACA moves forward and more women gain coverage. It is important to note that 17% of all women state they received contraceptives at “some other place,” such as a drugstore where condoms can be purchased.

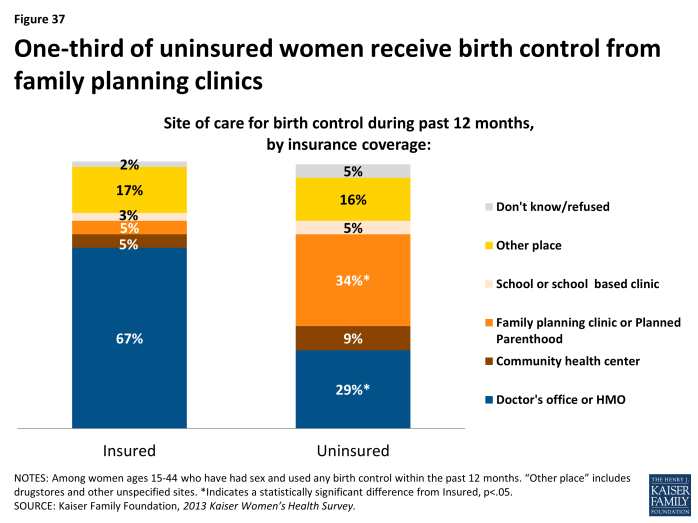

As with gynecologic exams, care seeking patterns differ between women with insurance and women who are uninsured, with uninsured women reporting much higher rates of obtaining contraceptives at family planning clinics such as Planned Parenthood (34%) compared to women with insurance (5%) (Exhibit 6.11). Only 29% of uninsured women receive birth control care from a doctor’s office or HMO.

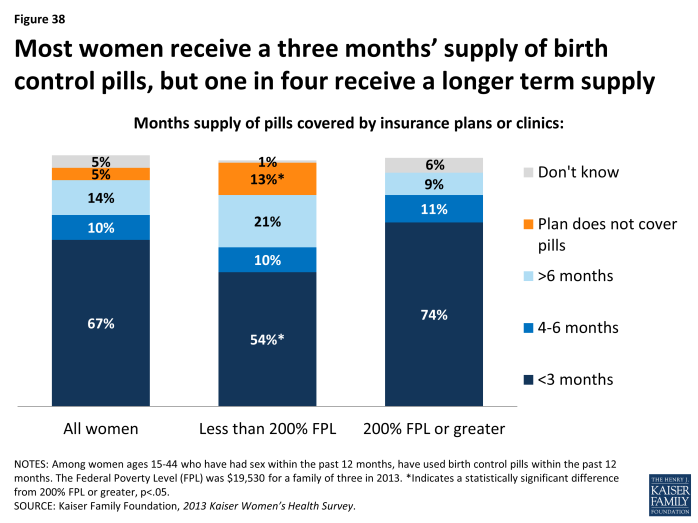

Among women who use oral contraceptives, most women typically receive 3 months’ supply at a time.

Women who use oral contraceptives must take a pill every day; therefore having an adequate supply is important for consistent and effective use.11Nearly three in ten (28%) of those who take birth control pills report that they have missed a pill because they could not get next pack on time (data not shown). Among women who have used oral contraceptives in the past year, two-thirds (67%) reported their plan or clinic allows them to only get 3 months’ supply or less at a time (Exhibit 6.12). A higher share of low-income women, however, say that their clinic or insurance covered a longer supply of oral contraceptives. At the same time though, more than one in ten low-income women (13%) also report that their plan did not cover birth control pills. The differences in dispensing patterns may be a result of differences in insurance coverage policies or practice variation between sites of care.

Awareness of the availability of emergency contraceptive (EC) pills is high, but only a fraction of women have purchased or used it.

Emergency contraception (EC), which is contraception that can be used after sex to prevent pregnancy, has been available in the U.S. since 1999. There are multiple forms, including the copper IUD, Plan B® pills, and more recently another form of EC pills, ella®, was approved by the FDA in 2010. Most forms require a prescription, except for Plan B®, which has been available without a prescription for women 17 and older since 2009. As with other contraceptives, new private plans are required to cover prescriptions for EC without cost sharing under the ACA’s preventive services policy.

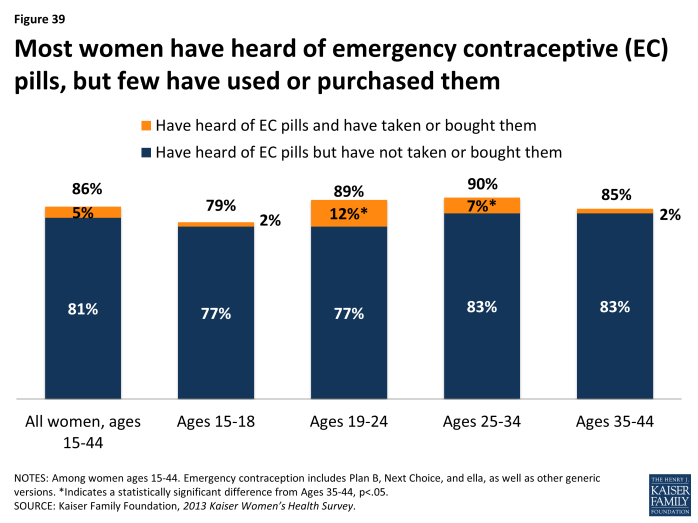

It has now been 15 years since EC pills were approved by the FDA and awareness of EC among women is very high. On average, 86% of women ages 15 to 44 report that they have heard of EC pills (Exhibit 6.13). Only a fraction of women (5%) have used or bought EC pills. Use is highest among women in their late teens and early twenties.

Contraceptive Coverage

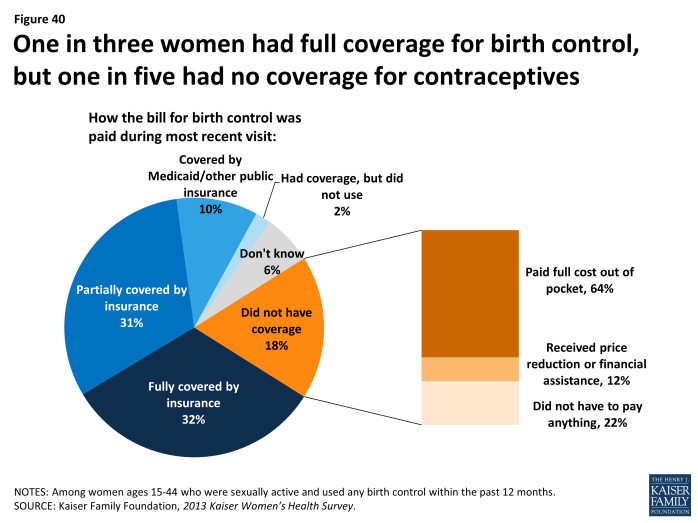

Among sexually active women who used contraception in the past year, three-quarters say that their insurance or Medicaid paid for some or all of the costs. However, nearly one in five say they had no coverage for their contraceptives, and most of these women paid the full cost out of pocket.

One of the most publicized and discussed of the ACA’s preventive services benefits is the requirement that most new private plans cover without cost sharing prescription contraceptive services and supplies. This policy went into effect August 2012.

Among sexually active women who report using contraception in the last year, insurance covered the full cost for one-third (32%) of women (Exhibit 6.14). Almost another one-third of women (31%) reported that insurance covered part of the costs, which could be because they are enrolled in an older private plan that is still “grandfathered” from ACA requirements or they used a particular contraceptive that is not covered by the requirement (such as condoms or a brand name drug), or they did not meet all the requirements (such as staying within the provider network). Family planning is a mandatory service under Medicaid and the program has covered contraceptives without cost sharing for decades. One in ten women who used birth control reported that Medicaid or another public program covered the costs of their contraceptives. Nearly one in five (18%) women reported they did not have any coverage for birth control, which could be due to lack of insurance or enrollment in a “grandfathered” plan (that does not have to cover preventive services). Among women without contraceptive coverage, nearly two-thirds (64%) paid the full cost out of pocket, 12% received a reduced price or financial assistance and 22% did not have to pay anything, presumably because they obtained free contraceptives at a clinic or through another assistance program.

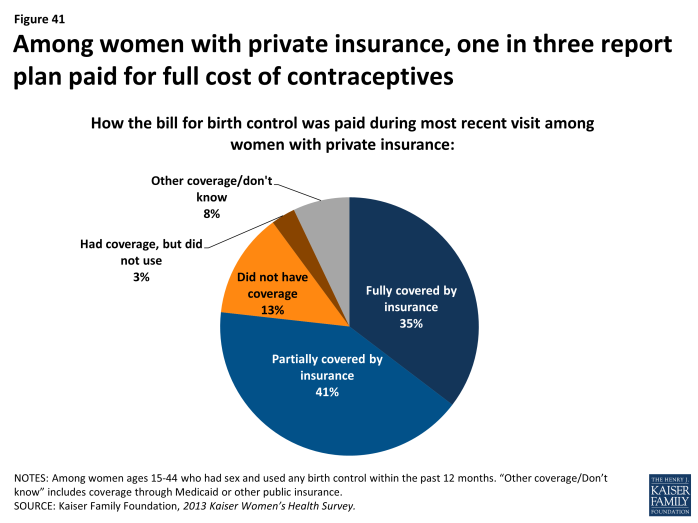

About one in three women who use contraception and have private insurance say their plan covered the full cost of the contraceptives.

It is notable that by the end of 2013, just over one-third (35%) of sexually active women who use birth control reported that their insurance fully covered the cost of contraceptives. Another 41% of women who used contraceptives last year said that insurance covered part of the costs (Exhibit 6.15). Over one in ten (13%) report that they did not have any coverage for contraceptives under their insurance. Almost all women with insurance for contraceptives (97%, data not shown) report that they did not have trouble getting their insurance to cover the costs (fully or partially) for prescribed contraceptives. Only a small fraction of women (3%) had problems getting insurance to pay.

Insurance and Confidentiality

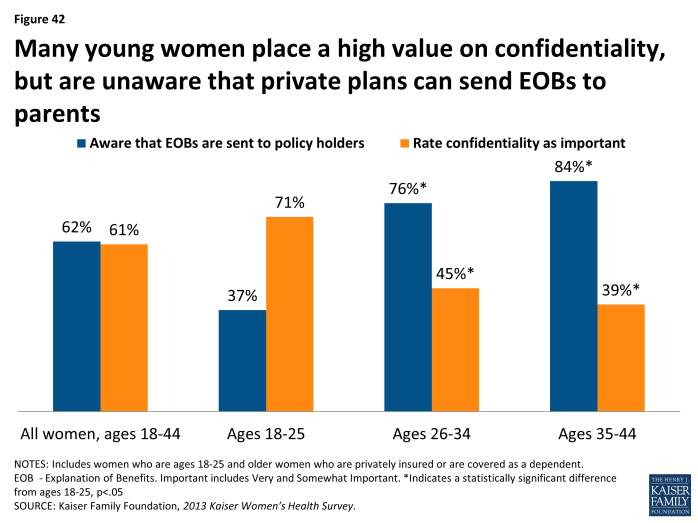

Women of all ages, but especially young women, value confidentiality. Many are not aware that private insurance plans can send documentation to the primary policy holder (such as a parent or spouse) that details the services they use.

Nearly half of women 18 to 25 (45%) with employer sponsored coverage are covered as dependents under their parents plan. Some of these women may have been able to obtain or keep private insurance through the ACA’s extension of dependent coverage up to age 26. Because these individuals are adult children, the extension of coverage has raised concerns about maintaining privacy and confidentiality about use of health services. Overall, six in ten women 18 to 44 years old report that it is important to them that information about health care visits be kept confidential from a parent or spouse (Exhibit 6.16). However, it is a higher priority among young women, who also have the lowest awareness of the private insurance industry practice of sending documentation known as an explanation of benefits (EOB) with details about services and costs of services that were paid for by insurance to primary policy holders, often a parent or spouse. Among women 18 to 25, 71% state that it is important to them that their use of health services, such as sexual or mental health care services, be kept confidential. Despite the importance of confidentiality, awareness of this practice was low among this age group, as only 37% of women knew that private insurers typically send an EOB to primary policy holders, often a parent. Awareness is even lower among teens ages 15 to 18, where only 24% reported knowing that EOBs were typically sent to the home (data not shown). Knowledge is considerably higher among women in older age groups, who likely have had greater experience with use of insurance plans.