What Are the Implications for Medicare of the American Health Care Act?

An important question in the debate over repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is what will happen to the law’s many provisions affecting the Medicare program. The American Health Care Act (AHCA), which recently passed the House Energy & Commerce and Ways & Means Committees, would leave most ACA changes to Medicare intact, including the benefit improvements (no-cost preventive services and closing the Part D coverage gap), reductions to payments to health care providers and Medicare Advantage plans, the Independent Payment Advisory Board, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation.

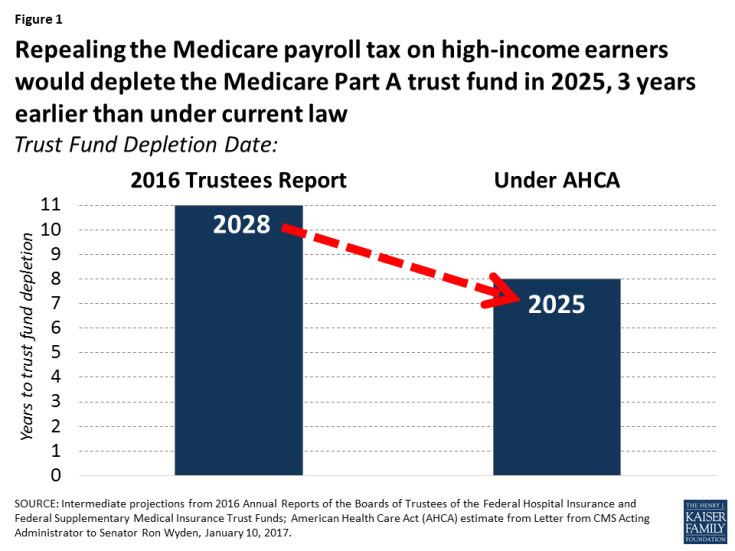

However, the AHCA would repeal the Medicare payroll surtax on high-income earners, along with virtually all other tax and revenue provisions in the ACA.1 Repealing this surtax would reduce revenue to the Medicare Hospital Insurance (Part A) trust fund by $117 billion between 2017 and 2026, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. It would also weaken Medicare’s financial status by depleting the Part A trust fund three years sooner than under current law, moving up the projected insolvency date from 2028 to 2025, based on estimates by Medicare’s actuaries2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Repealing the Medicare payroll tax on high-income earners would deplete the Medicare Part A trust fund in 2025, 3 years earlier than under current law

The Medicare Part A trust fund pays for hospital, skilled nursing facility, home health and hospice benefits. Under current law, Part A is financed primarily through a 2.9% tax on earnings paid by employers and employees (1.45% each). The ACA increased the payroll tax for a minority of taxpayers with relatively high incomes—those earning more than $200,000/individual and $250,000/couple—by 0.9 percentage points.

The AHCA’s changes to the ACA’s marketplace coverage provisions and the per capita cap proposal for Medicaid would also increase the number of uninsured, according to the Congressional Budget Office, putting additional strain on the nation’s hospitals to provide uncompensated care. This would increase Medicare “disproportionate share hospital” (DSH) payments as a result, which would increase Medicare Part A spending by $43 billion between 2018 and 2026, according to CBO.

Reducing the flow of revenues to the trust fund by repealing the Part A payroll surtax paid by high-income earners and increasing Part A spending due to higher DSH payments has direct implications for the ability of Medicare to pay for Part A benefits on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries. When spending on Part A benefits exceeds revenues, and assets in the Part A trust fund account are fully depleted, Medicare will not have sufficient funds to pay all Part A benefits (although the Medicare program will not cease to operate).

In addition to the impact on Medicare’s solvency in the short term, repealing the high-income earner payroll surtax would also worsen the program’s long-run financial status. Cutting off this revenue stream would increase the 75-year shortfall in the Part A trust fund from 0.73% of taxable payroll to 1.12%.

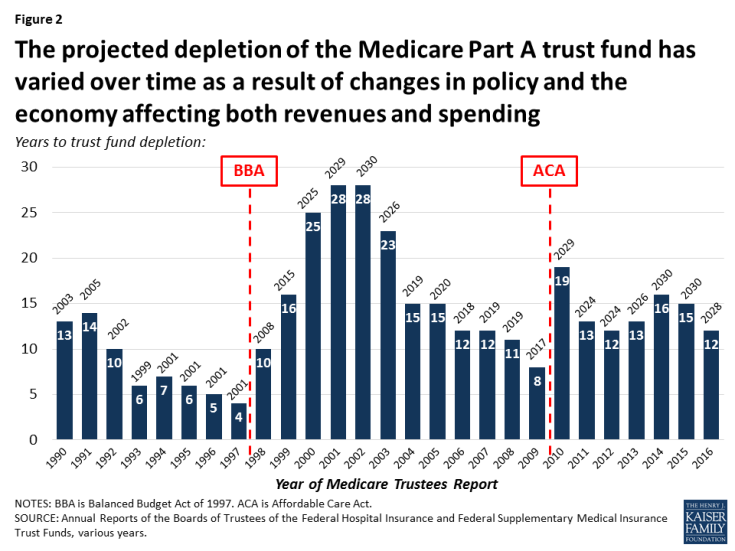

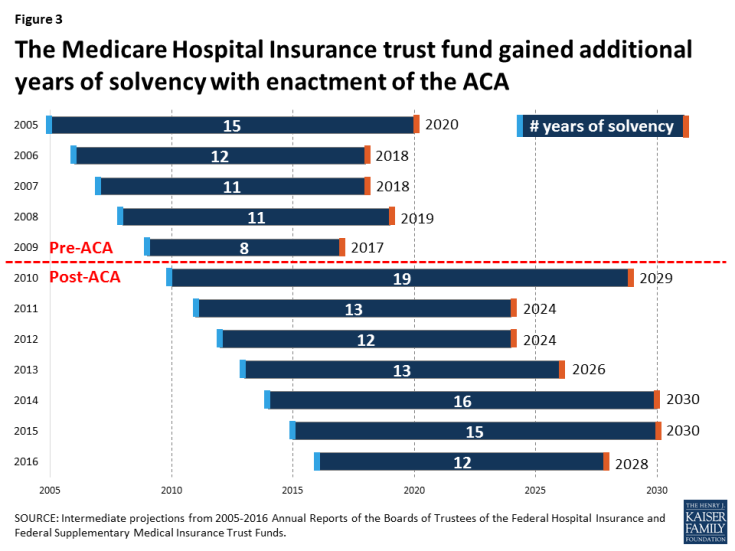

The projected date for depletion of the Medicare Part A trust fund has varied over time as a result of changes in policy and the economy affecting both revenues and spending (Figure 2). In the past, looming insolvency has prompted policymakers to debate and pass legislation that reduced Medicare spending, thereby improving the financial status of the Part A trust fund. For example, during the mid-1990s, when the Medicare actuaries were projecting trust fund insolvency by 2001, Congress enacted the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997, which reduced Medicare spending and extended the solvency of the Part A trust fund by an additional seven years. With the enactment of the ACA in 2010, Congress added several years to Part A trust fund solvency as a result of the law’s provisions to increase the Medicare payroll tax on high-income earners and reduce provider and plan payments (Figure 3).

Figure 2: The projected depletion of the Medicare Part A trust fund has varied over time as a result of changes in policy and the economy affecting both revenues and spending

Figure 3: The Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund gained additional years of solvency with enactment of the ACA

Whether the Part A trust fund remains solvent for an additional 11 years as projected under current law, or only 8 years if the payroll tax is repealed, Medicare faces long-term financial pressures associated with higher health care costs and an aging population. Even if the ACA payroll tax on high earners is retained, the Medicare Part A trust fund is likely to need additional revenue to finance care for an aging population, unless policymakers choose instead to reduce Part A spending by cutting benefits, restricting eligibility, or reducing payments to providers and plans. By cutting taxes on high-income earners and thereby reducing revenue to the Medicare Part A trust fund, the AHCA would increase pressure on policymakers to take some type of action sooner rather than later.