Views and Experiences with End-of-Life Medical Care in Japan, Italy, the United States, and Brazil: A Cross-Country Survey

Key Findings Across Countries

Perceptions of the Aging Population and Preparedness of Government, Health System, and Families

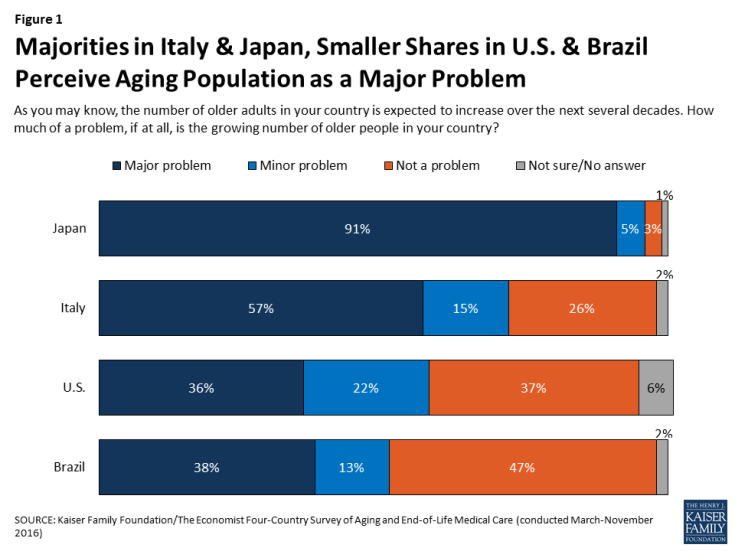

Across the four countries surveyed, the share of the public perceiving population aging as a major problem corresponds roughly to each country’s place on the aging trajectory. Nine in ten adults in Japan and about six in ten in Italy (the two “older” countries in the survey) see the growing number of older people in their country as a major problem, compared with about four in ten in the “younger” countries of the U.S. and Brazil.

Figure 1: Majorities in Italy & Japan, Smaller Shares in U.S. & Brazil Perceive Aging Population as a Major Problem

Across all four countries surveyed, majorities say the government is “not too prepared” or “not at all prepared” to deal with the aging population. Preparedness ratings are somewhat more mixed when it comes to the country’s health care system and families. In Italy and Brazil, majorities see the health care system as unprepared, while residents of the U.S. and Japan are more evenly divided between thinking the health care system is prepared and not prepared. Asked how prepared families are to deal with the aging population, majorities in Italy, Japan, and Brazil say families are not prepared, while Americans are more evenly split.

Figure 2: Across Countries, Many See Government, Health System, and Families as Unprepared to Deal with Aging Population

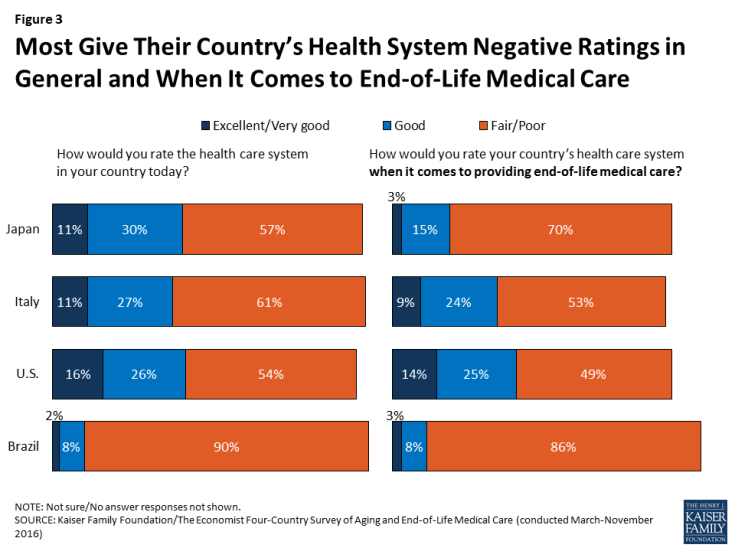

Another similarity across countries is in residents’ relatively negative ratings of their health care systems. In each country, the public is more likely to rate their health care system as “fair” or “poor” than to say it is “excellent” or “very good.” This is true when residents are asked to rate the health care system in general and also when they are asked about end-of-life medical care specifically. Residents of Brazil – a country whose state-run health care system has been plagued by problems – are particularly negative on these measures, with about nine in ten giving a “fair” or “poor” rating.

Figure 3: Most Give Their Country’s Health System Negative Ratings in General and When It Comes to End-of-Life Medical Care

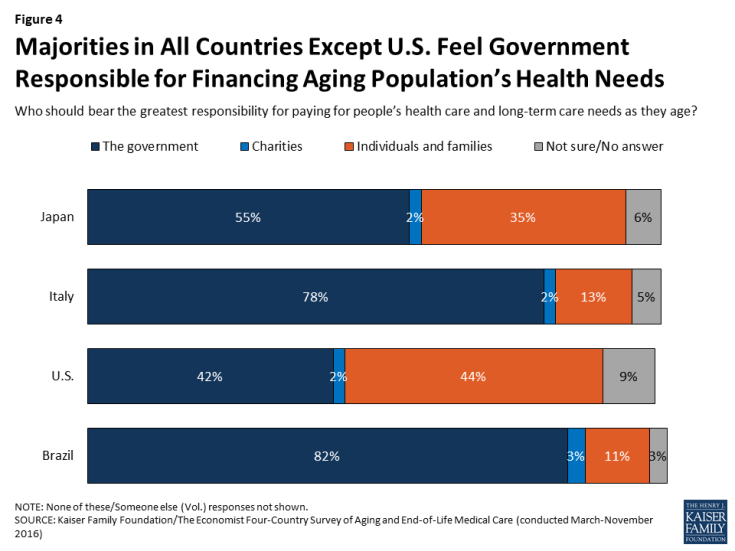

Residents of the four countries differ somewhat in their views of who should bear the greatest responsibility for financing care for an aging population. In Italy and Brazil, large majorities of around eight in ten say it’s the government’s responsibility to pay for people’s health and long-term care needs as they age, as do just over half in Japan. Views in the U.S. are more evenly split between those who say the responsibility should fall mostly on individuals and families (44 percent) and those who say it’s the responsibility of the government (42 percent). These views are largely divided by party identification, as views of government responsibility generally are in the U.S., with Democrats more likely to place the responsibility on government and Republicans more likely to place it on families.

Figure 4: Majorities in All Countries Except U.S. Feel Government Responsible for Financing Aging Population’s Health Needs

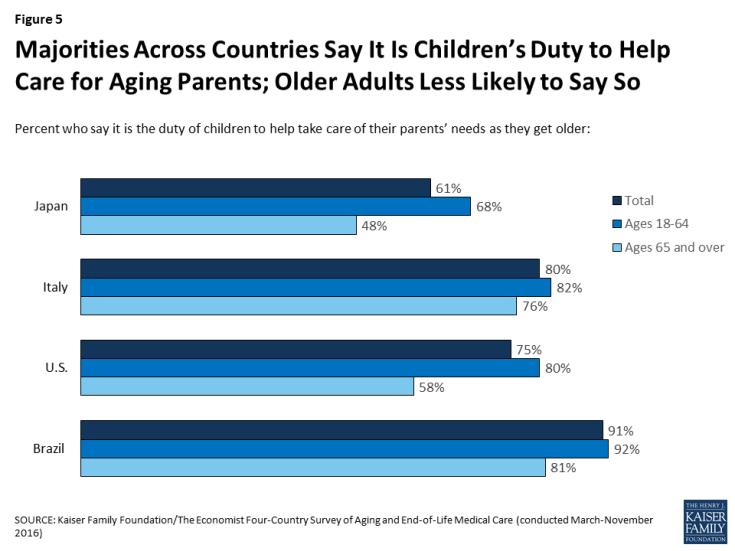

Outside of financial responsibility, most people across countries see a large role for families in helping aging family members. Solid majorities say that it is the duty of children to help take care of their parents’ needs as they get older, ranging from 61 percent in Japan to 91 percent in Brazil. With the exception of Italy, in each country older adults themselves are less likely than their younger counterparts to say it is the children’s duty.

Figure 5: Majorities Across Countries Say It Is Children’s Duty to Help Care for Aging Parents; Older Adults Less Likely to Say So

Priorities at the End of Life

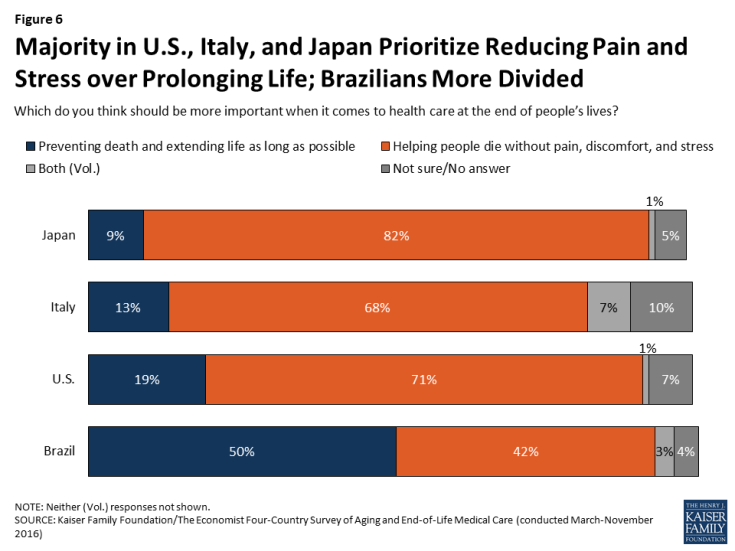

The survey reveals a difference between residents of Brazil and those of the other three countries surveyed when it comes to the relative priority placed on extending life. When asked what should be more important when it comes to health care at the end of people’s lives, half of Brazilians (50 percent) choose “preventing death and extending life as long as possible” while about four in ten (42 percent) choose “helping people die without pain, discomfort, and stress.” This stands in contrast to Japan, Italy, and the U.S., where large majorities – between 68 percent and 82 percent – prioritize reducing pain and stress over extending life.

Figure 6: Majority in U.S., Italy, and Japan Prioritize Reducing Pain and Stress over Prolonging Life; Brazilians More Divided

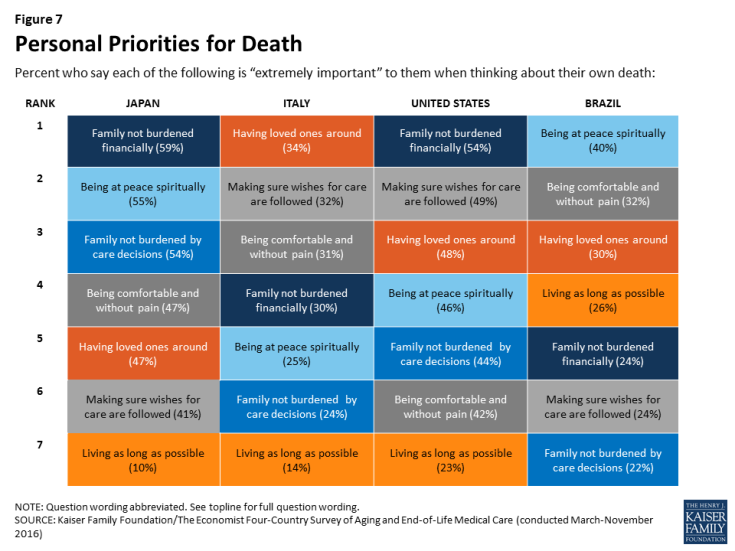

Similarly, when asked what is important in thinking about their own death, Brazilians stand out in the relative importance placed on extending life. In Japan, Italy, and the U.S., “living as long as possible” ranks last on the list of seven possible factors, with a substantially lower share saying it is “extremely important” to them compared with any other factor. By contrast, “living as long as possible” ranks fourth in Brazil, with 26 percent saying it is “extremely important,” similar to the shares who say the same about other priorities like having loved ones around and not burdening one’s family financially. These differences between Brazil and the other countries surveyed may have something to do with Brazil’s relatively younger population; across countries, younger adults are generally more likely than older adults to place greater emphasis on extending life.

In terms of what is most important to people in thinking about their own death, in the U.S. and Japan, where medical care is generally expensive, “making sure your family is not burdened financially by your care” ranks at the top of the list.1 In Italy, the top concern is “having loved ones around you,” followed closely by “making sure your wishes about medical care are followed” and “being comfortable and without pain.” In Brazil, the top concern is “being at peace spiritually.”

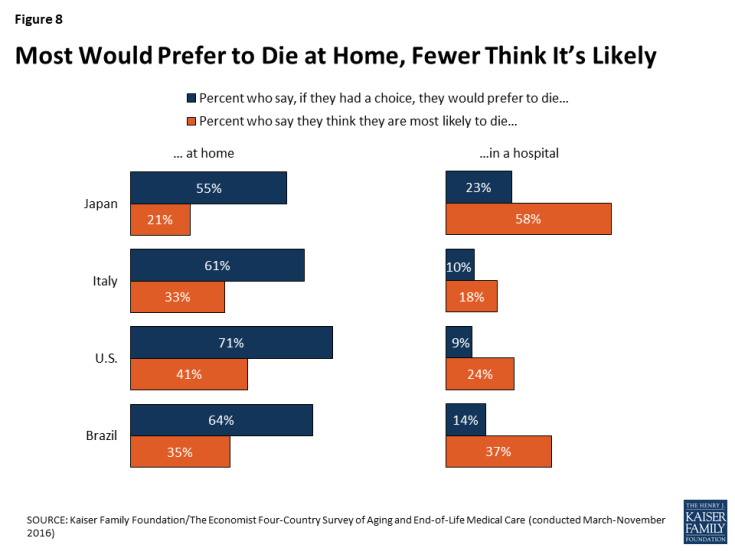

In considering their own death, individuals across countries share the desire to die at home, along with the expectation that this desire is not likely to be fulfilled. Across the four countries surveyed, majorities say if they had the choice, they would prefer to die at home. However, when asked where they think they are most likely to die, a much smaller share in each country say they expect to die at home. This pattern is starkest in Japan – a country with 13.4 hospital beds per 1,000 residents (roughly 4 times as many as any other country surveyed) – where 55 percent say they would prefer to die at home, but 58 percent think they are most likely to die in a hospital.2

Who Should Have Control of Medical Decisions at the End of Life?

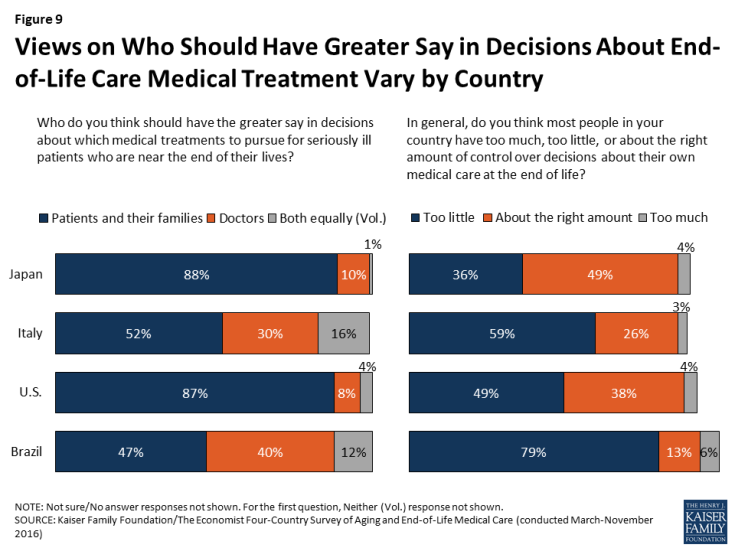

There is some variation across the countries surveyed in views of whether doctors or patients and their families should have the greater say in decisions about end-of-life medical treatments. The vast majority of adults in Japan (88 percent) and the U.S. (87 percent) say that patients and their families should have the greater say, while closer to half in Italy (52 percent) and Brazil (47 percent) say the same. By contrast, substantial shares of Brazilians (40 percent) and Italians (30 percent) say that doctors should have the greater say in which medical treatments to pursue for seriously ill patients who are near the end of their lives, compared with about one in ten in Japan and the U.S.

Interestingly, however, the two countries surveyed (Brazil and Italy) where residents are least likely to say patients and their families should have the greater say in end-of-life medical decisions are also the most likely to say people in their own country have too little control over decisions about their own medical care at the end of life (79 percent and 59 percent, respectively). About half (49 percent) of U.S. adults also feel that people have too little control over these decisions. In Japan, about half (49 percent) feel that people in their country have about the right amount of control, while a smaller share (36 percent) say they have too little.

Figure 9: Views on Who Should Have Greater Say in Decisions About End-of-Life Care Medical Treatment Vary by Country

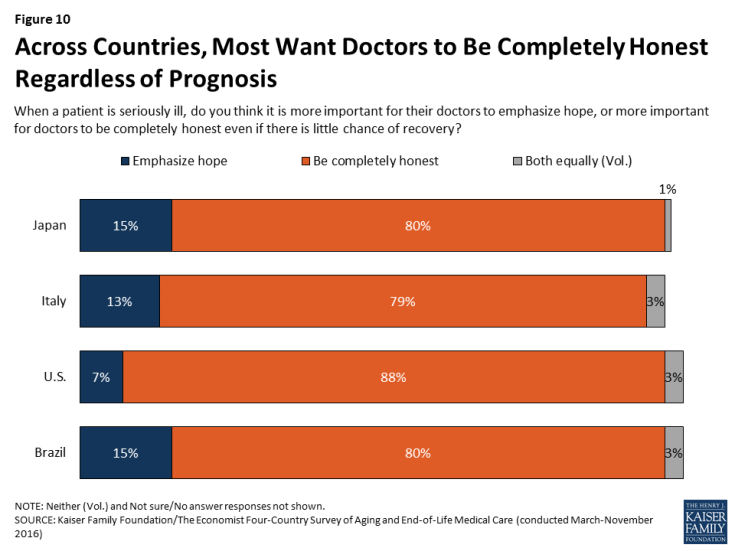

Despite these differences, most people across the countries surveyed agree that doctors should be honest with patients regardless of their prognosis. Large majorities say that when a patient is seriously ill, it is more important for doctors to be completely honest even if there is little chance of recovery, while a small share across countries believe it is more important for doctors to emphasize hope for seriously ill patients.

Talking about Death and Planning Ahead

Across countries, majorities say death is a subject that is generally avoided rather than something people feel free to talk about. However, the U.S. stands out from other countries, with higher shares reporting having conversations with loved ones about end-of-life wishes and having these wishes written down.

When it comes to the subject of death, majorities ranging from 57 percent in Japan to 69 percent in the U.S. say that death is a subject that is generally avoided in their country’s society, while much smaller shares (ranging from 26 percent in the U.S. to 38 percent in Japan) say death is a subject people generally feel free to talk about.

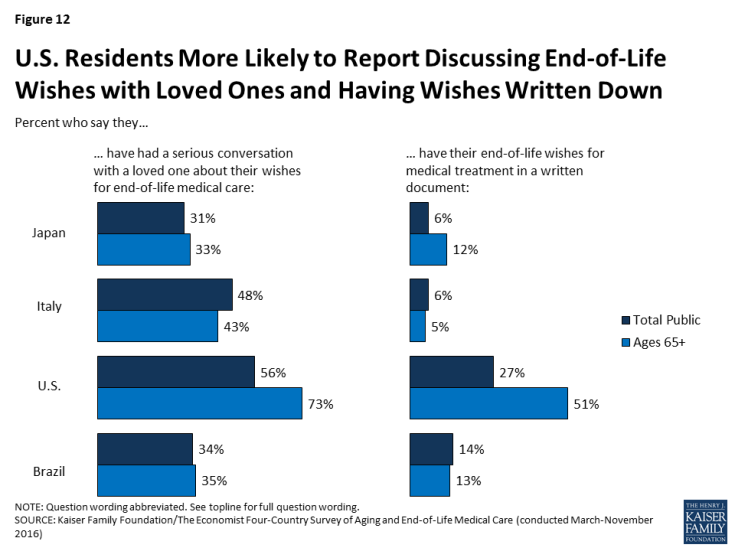

This reluctance to talk about death is reflected in people’s self-reported conversations. Fewer than half of adults (including those ages 65 and over) in Italy, Japan, and Brazil say they’ve had a serious conversation with a loved one about their own wishes for end-of-life medical care. These conversations are somewhat more common in the U.S., with just over half the general population and about three-quarters of Americans ages 65 and over saying they’ve had such a conversation. Having one’s end-of-life medical wishes in a written document is also more common in the U.S.; a quarter of U.S. adults (27 percent) and half of U.S. seniors (51 percent) say they do, compared with fewer than 1 in 6 in other countries.

Figure 12: U.S. Residents More Likely to Report Discussing End-of-Life Wishes with Loved Ones and Having Wishes Written Down

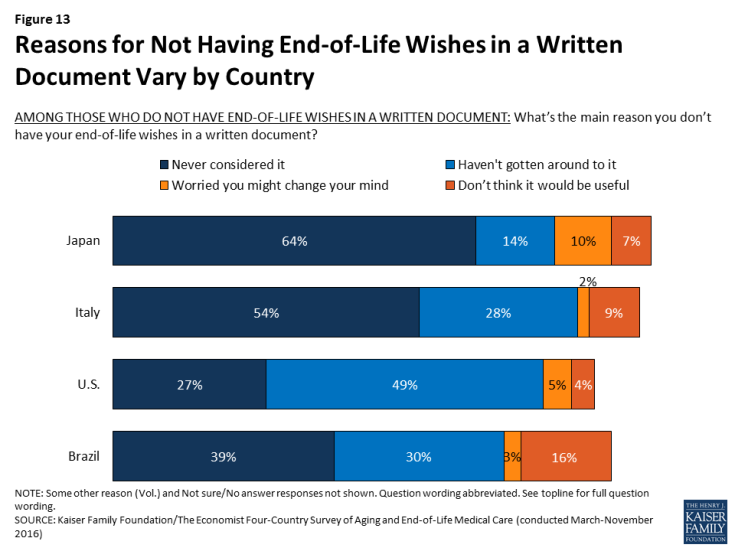

Among those who do not have their wishes written down, the top reason in Italy, Japan, and Brazil is “you never considered it,” suggesting that writing down one’s wishes is not a commonly discussed practice in these countries. By contrast, the top reason in the U.S. is “you just haven’t gotten around to it,” suggesting that Americans are more likely than residents of the other countries surveyed to think of writing down their medical wishes as a common practice and something they expect to do at some point in their lives.

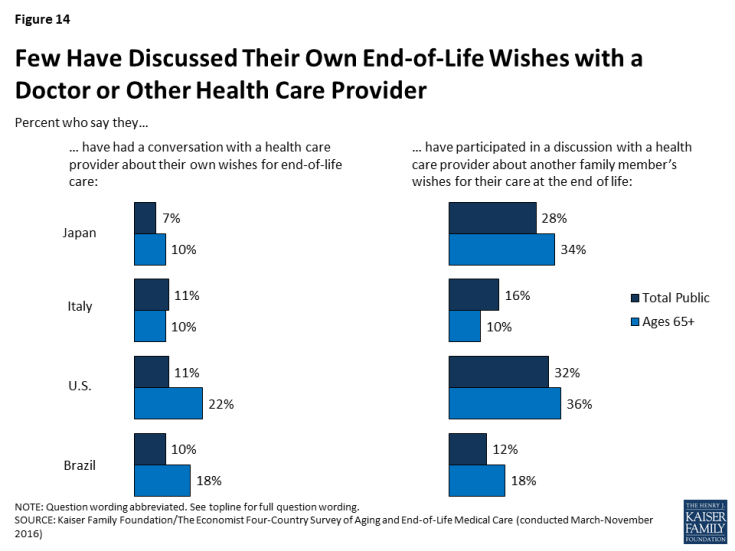

If conversations with loved ones about end-of-life wishes are relatively uncommon, conversations with health care professionals about these issues are even rarer. Just about one in ten in each country say they’ve had a conversation about their wishes for end-of-life medical treatment with a doctor or other health care provider, rising to 22 percent among seniors in the United States. A somewhat larger share – roughly three in ten – in the U.S. and Japan say they’ve participated in a discussion with a health care provider about another family member’s wishes for their care at the end of life, but still the majority say they have not participated in such a conversation.

Figure 14: Few Have Discussed Their Own End-of-Life Wishes with a Doctor or Other Health Care Provider

Experiences with Death of a Loved One

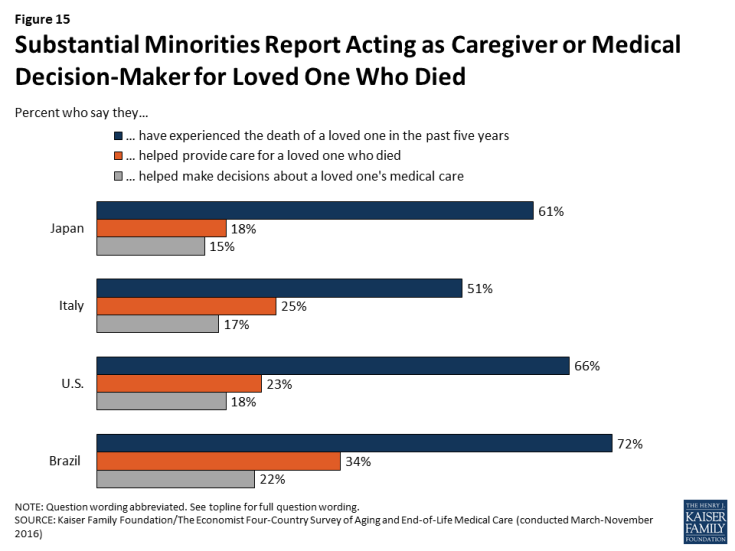

At least half of people in each of the four countries surveyed report experiencing the death of someone close to them within the past five years, including substantial minorities who say they helped provide care or helped make medical decisions for the person who died. Overall, about one-fifth in Japan, one-quarter in the U.S. and Italy, and one-third in Brazil say they helped to provide care for a loved one who died in the past five years. About one in five in each country say they were involved in helping to make medical decisions for someone who died in that time frame.

Figure 15: Substantial Minorities Report Acting as Caregiver or Medical Decision-Maker for Loved One Who Died

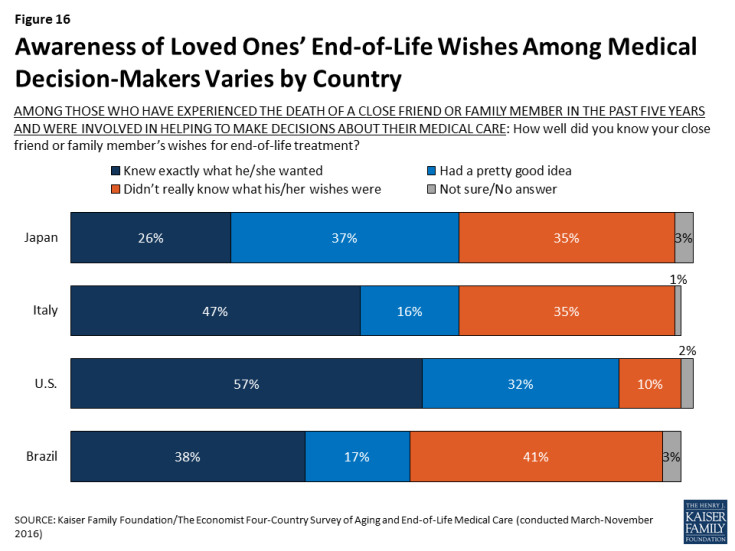

Among those who say they acted as a medical decision-maker for a loved one who died, residents of the U.S. are more likely than residents of the other countries surveyed to say they had a good idea of their loved one’s end-of-life wishes. A majority of Americans who served as a medical decision-maker for someone who died say they knew exactly what the person wanted (57 percent) or had a pretty good idea (32 percent), while just one in ten say they didn’t really know what their loved one wanted. By contrast, between a third and four in ten in Japan, Italy, and Brazil say they didn’t really know what their loved one’s wishes were before they died. This difference may be related to the finding noted above that Americans are more likely to report having conversations with loved ones about end-of-life wishes.

Figure 16: Awareness of Loved Ones’ End-of-Life Wishes Among Medical Decision-Makers Varies by Country

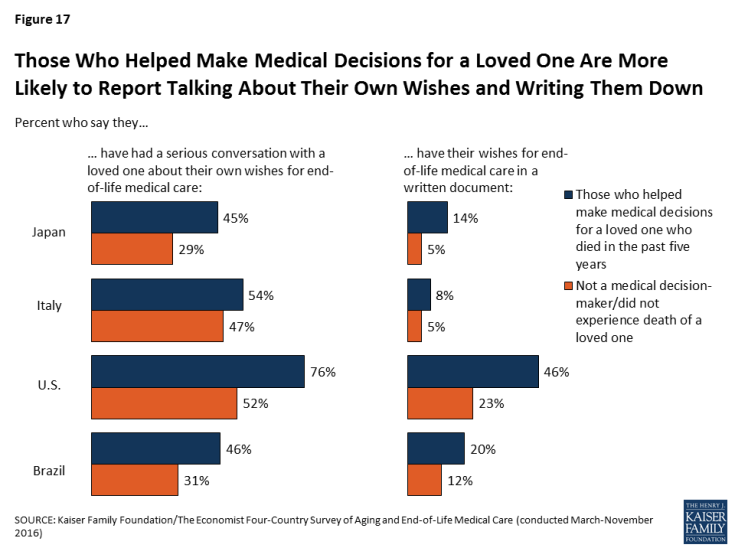

Acting as a medical decision-maker for someone who died also appears to influence people’s own personal end-of-life preparations; in Japan, the U.S., and Brazil, those who served as a medical decision-maker for someone else are significantly more likely to say they’ve had a serious conversation with a loved one about their own end-of-life wishes, and to have those wishes in a written document.

Figure 17: Those Who Helped Make Medical Decisions for a Loved One Are More Likely to Report Talking About Their Own Wishes and Writing Them Down

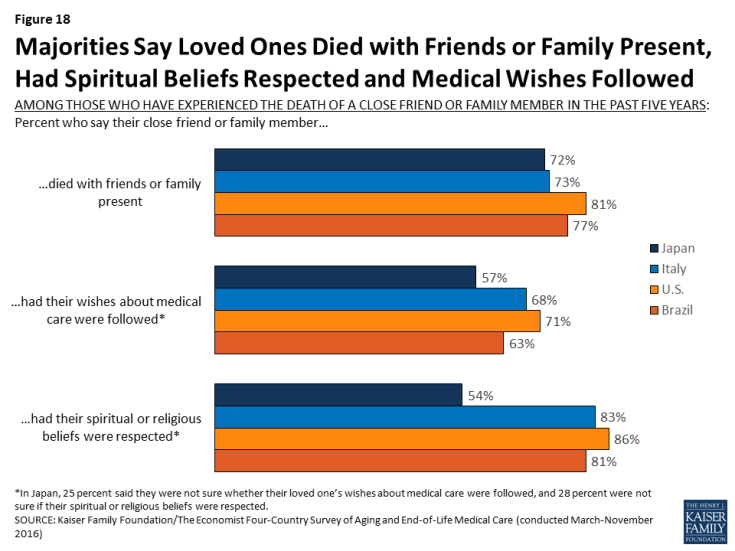

While most of those who experienced the death of a loved one report positive experiences overall, some negative reports are not uncommon. Among those who experienced the death of someone close to them in the past five years, majorities across countries say their loved one’s wishes about medical care were followed, that their spiritual and religious beliefs were respected, and that they died with friends or family present.

Figure 18: Majorities Say Loved Ones Died with Friends or Family Present, Had Spiritual Beliefs Respected and Medical Wishes Followed

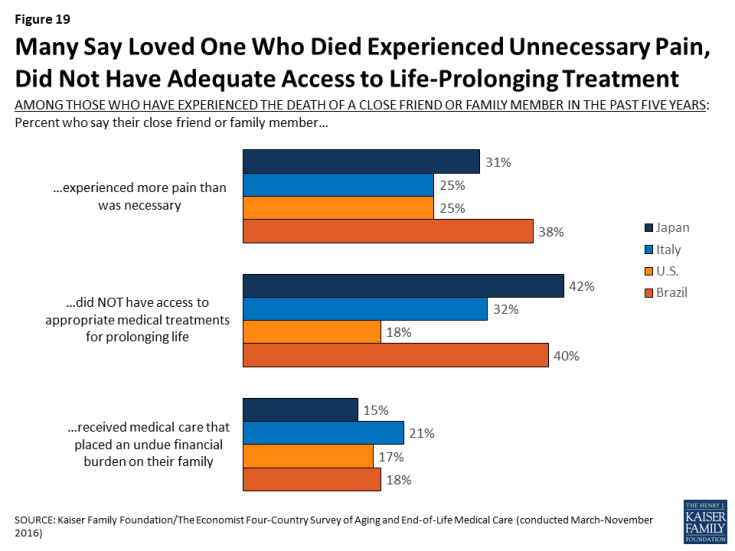

Still, substantial shares of those who experienced the death of a loved one – particularly in Japan and Brazil – say the person experienced more pain than was necessary (about four in ten in Brazil, three in ten in Japan, and a quarter in the U.S. and Italy) or that they did not have access to appropriate medical treatments for prolonging life (about four in ten in Japan and Brazil, one-third in Italy, and 18 percent in the U.S.). About one in five of those experiencing the death of a loved one across countries say their loved one received medical care that placed an undue burden on the patient’s family.

Figure 19: Many Say Loved One Who Died Experienced Unnecessary Pain, Did Not Have Adequate Access to Life-Prolonging Treatment

Awareness and Opinions of Hospice Care

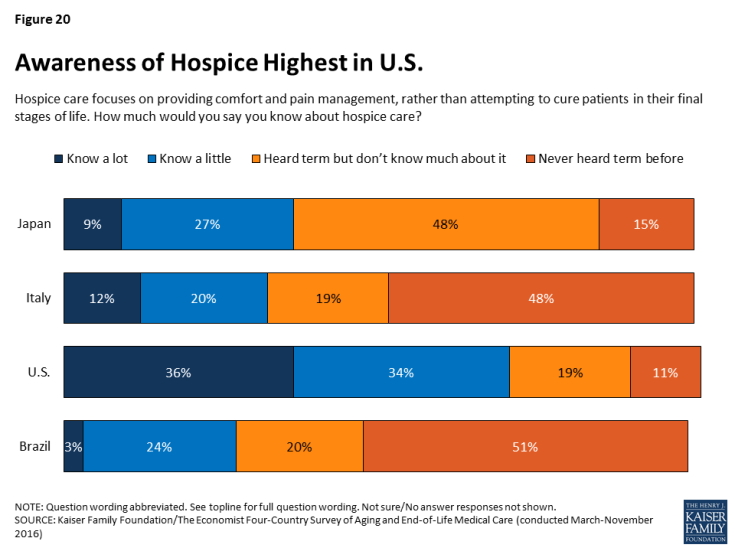

Hospice care is an option for seriously ill patients near the end of life that emphasizes providing comfort and pain management rather than curative treatment. In the U.S., the use of hospice care has increased in recent years, and hospice services are provided in various settings, including hospitals, free-standing hospice centers, and often in the patient’s own home.3 In the other countries surveyed, hospice care is less common and is usually provided in a designated hospice facility. Reflecting these differences, adults in the U.S. are much more likely than those in Japan, Italy, or Brazil to say they know something about hospice. Seven in ten Americans say they know at least a little about hospice care, compared with between about a quarter and a third in the other countries surveyed.

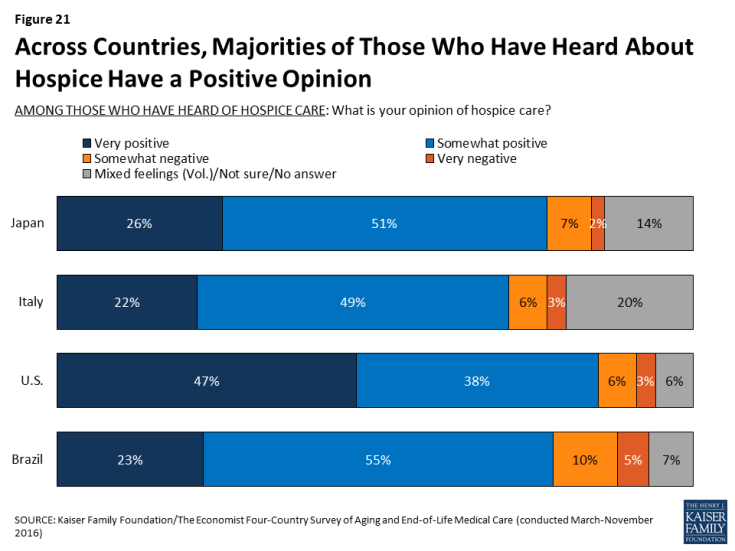

Among those who have heard of it, feelings about hospice care across countries are overwhelmingly positive, with large majorities (between seven and eight in ten) saying they have a positive opinion of hospice.

Figure 21: Across Countries, Majorities of Those Who Have Heard About Hospice Have a Positive Opinion

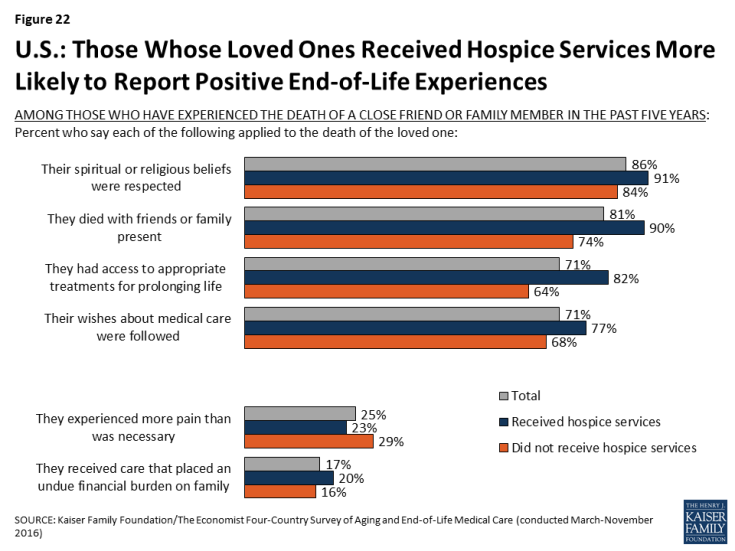

While relatively few of those who experienced the death of a loved one in Japan, Italy, and Brazil say that their loved one died in a hospice facility, roughly half (53 percent) of U.S. adults who experienced a death say their loved one either died in a hospice facility or was receiving hospice services before they died. In the U.S., those whose close friend or family member received hospice services are more likely than those who didn’t receive such services to say their loved one’s spiritual or religious beliefs were respected, that they died with friends or family present, and that their wishes about medical care were followed. Although the aim of hospice is to relieve pain and suffering and not necessarily to extend life, those whose loved ones received hospice services are also more likely than those who didn’t to say the person had access to appropriate treatments for prolonging life. However, there is no significant difference based on receipt of hospice services in the share who say their loved one experienced more pain than necessary or received care that placed an undue financial burden on the family.