To Switch or Be Switched: Examining Changes in Drug Plan Enrollment among Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy Enrollees

Key Findings

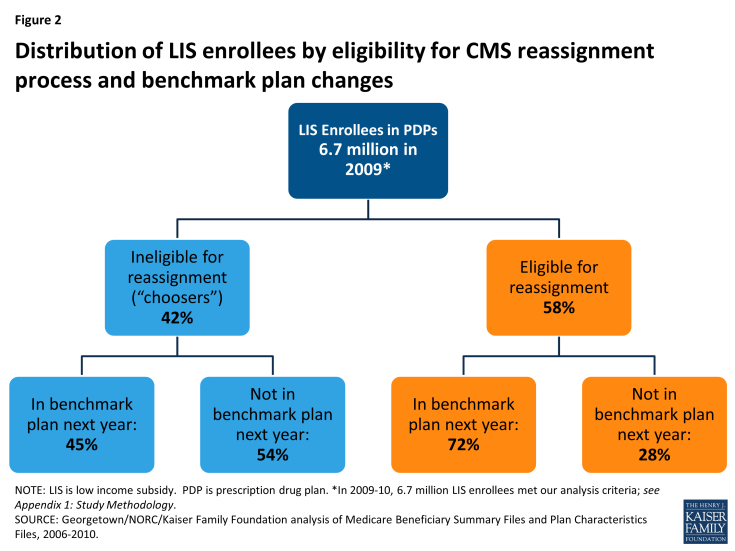

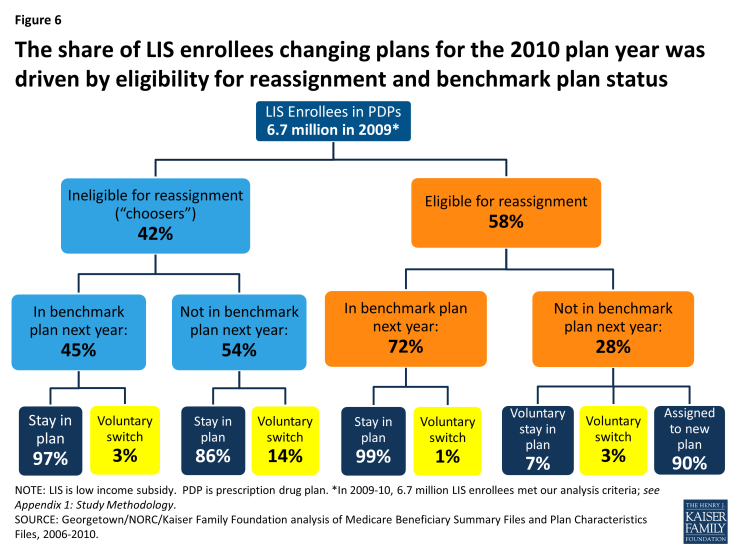

Of the LIS beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs at the end of 2009, a majority (58 percent) were eligible for reassignment to new PDPs by CMS in the event that their plan lost its premium-free (benchmark) status, while four in ten (42 percent) were not eligible for reassignment because they had voluntarily chosen to enroll in their current plan.

In December 2009, an estimated 3.9 million LIS beneficiaries in PDPs (out of about 6.7 million who met our analysis criteria) were eligible for reassignment to new PDPs by CMS if their plans no longer qualified as premium-free plans for 2010. The remaining 2.8 million LIS PDP beneficiaries were ineligible for CMS reassignment and were responsible for considering their own options for switching to new plans.

More than half (54 percent) of LIS enrollees ineligible for reassignment (“choosers”) were in PDPs losing benchmark status for 2010, compared to only 28 percent of LIS enrollees eligible for reassignment (Figure 2).1 In other words, most (72 percent) LIS enrollees eligible for reassignment were in PDPs maintaining their premium-free benchmark status for 2010, compared to less than half (45 percent) of LIS enrollees not eligible for reassignment. The implication of this is that a greater share of LIS enrollees not eligible for reassignment would have to take action if they wanted to receive premium-free Part D coverage.

Figure 2: Distribution of LIS enrollees by eligibility for CMS reassignment process and benchmark plan changes

The share of LIS beneficiaries eligible for reassignment was somewhat higher (70 percent) at the end of the program’s first year, but was fairly constant from December 2007 through the end of 2010 (Table 1). The share in this category appears to have stabilized as the numbers newly selecting a plan on their own are offset by the entry of new Part D enrollees being assigned to a plan for the first time.2

| Table 1: Distribution of Part D LIS PDP Enrollees, by Eligibility for Reassignment, 2006-2010 | |||||

| December 2006 | December 2007 | December 2008 | December 2009 | December 2010 | |

| Percent eligible for reassignment | 70% | 54% | 58% | 58% | 56% |

| Percent ineligible for reassignment | 30% | 46% | 42% | 42% | 43% |

| Number eligible for reassignment | 4.8 million | 3.5 million | 3.9 million | 3.9 million | 3.8 million |

| Number ineligible for reassignment | 2.1 million | 3.0 million | 2.8 million | 2.8 million | 2.9 million |

| TOTAL | 6.9 million | 6.5 million | 6.6 million | 6.7 million | 6.7 million |

|

NOTE: LIS is low income subsidy. Estimates may not sum to totals due to rounding. Numerical counts are projected from the 5 percent sample and are smaller than the total number of LIS PDP beneficiaries because of sample exclusions and a small number of beneficiaries whose reassignment status could not be classified. The share of those eligible for reassignment may be somewhat understated, especially in 2007 and 2008, because of the incorrect assignment of enrollment status in the preliminary CMS dataset used in this study. See Appendix 1: Study Methodology.

SOURCE: Georgetown/NORC/Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Medicare Beneficiary Summary Files and Plan Characteristics Files, 2006-2010.

|

|||||

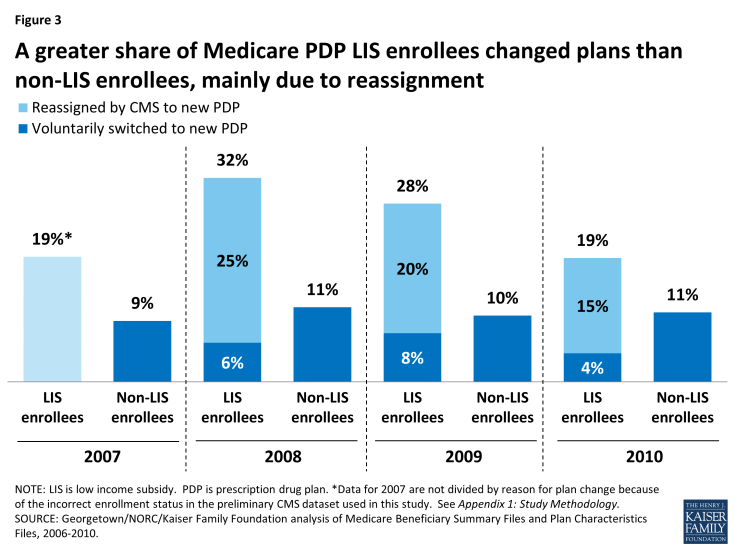

Overall, LIS beneficiaries in PDPs changed drug plans at a higher rate than non-LIS enrollees in 2010 (19 percent versus 11 percent), but this was primarily a result of assignment to a new plan by CMS rather than voluntary switching.

The 19 percent of LIS beneficiaries in PDPs who changed plans for 2010 includes 15 percent of LIS enrollees who were reassigned by CMS to new plans and 4 percent who switched plans voluntarily (Figure 3). Excluding plan changes resulting from the reassignment process, a much smaller share of LIS enrollees than non-LIS enrollees in PDPs switched plans on a voluntary basis (4 percent versus 11 percent). Factoring in plan changes resulting from the CMS reassignment process, however, results in a higher overall rate of plan changes among LIS enrollees in 2010.

Figure 3: A greater share of Medicare PDP LIS enrollees changed plans than non-LIS enrollees, mainly due to reassignment

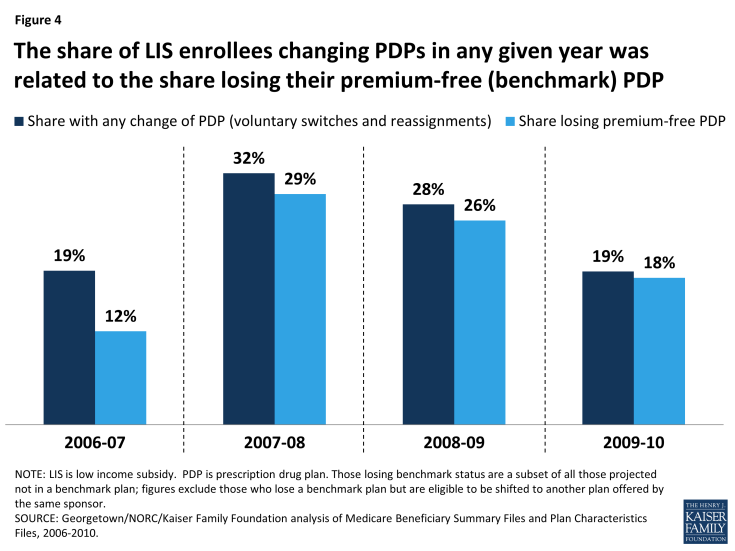

The pattern of voluntary switching and plan reassignments for LIS beneficiaries has varied considerably from year to year—especially the rate of being reassigned to new plans by CMS—due primarily to the changing availability of benchmark plans (Figure 4). Loss of premium-free (benchmark) plan status, resulting from the changing availability of benchmark plans, is the criterion used by CMS to reassign eligible LIS beneficiaries to new plans and is also likely a key factor in voluntary switching decisions by those LIS enrollees who are not eligible for reassignment because they have chosen their current plans. In our study period, 2008 had the highest rate of turnover in benchmark plan availability, and this year also had the highest combined rate of reassignment and voluntary switching among LIS beneficiaries.3 In 2008, one in three LIS beneficiaries (32 percent) were reassigned or switched to a new plan, compared to one in five in 2006 (20 percent) and 2010 (19 percent). 2008 also saw the greatest change in the availability of benchmark plans, affecting 29 percent of all LIS beneficiaries. By contrast, changing plan availability affected only 12 percent of LIS beneficiaries in 2007 and 18 percent in 2010 (see Appendix 1: Benchmark Plans for more information on benchmark plan availability).

Figure 4: The share of LIS enrollees changing PDPs in any given year was related to the share losing their premium-free (benchmark) PDP

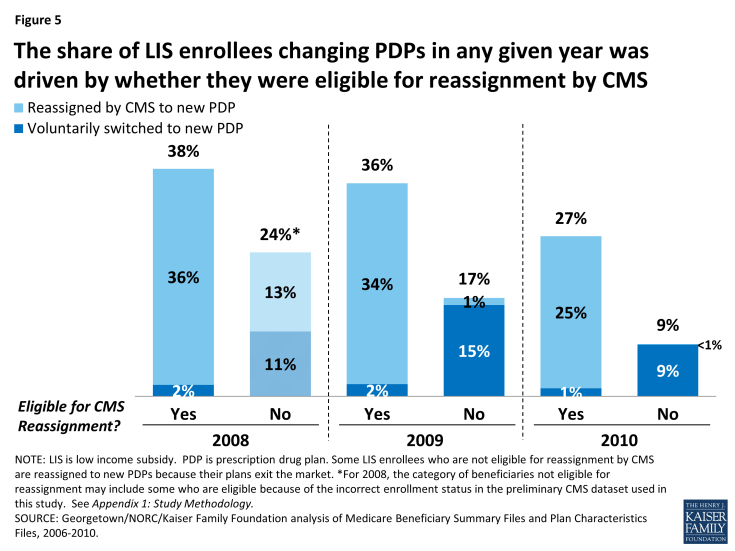

The share of LIS enrollees changing plans is higher among LIS beneficiaries who are eligible for reassignment to premium-free plans than among those who are not eligible for reassignment, who must make a voluntary decision to change plans (Figure 5). In 2010, three times as many LIS enrollees eligible for reassignment experienced a change of plans than LIS enrollees not eligible for reassignment; among the former group, 25 percent were reassigned to a new plan by CMS and 1 percent voluntarily chose a new plan, while among the latter group 9 percent voluntarily switched to a new PDP. Rates of changing plans were higher for both groups of LIS enrollees in 2008 and 2009, compared to 2010.4

Figure 5: The share of LIS enrollees changing PDPs in any given year was driven by whether they were eligible for reassignment by CMS

Among the subgroup of LIS beneficiaries who were not eligible for reassignment and whose plans were losing benchmark status for 2010 (about one-fourth of all LIS enrollees in PDPs), few (14 percent) switched voluntarily during the annual enrollment period for 2010, despite receiving notices from CMS reminding them that they would face premiums if they did not switch plans. Most who were eligible for reassignment by CMS accepted that assignment.

Only 14 percent of those LIS beneficiaries who faced a premium payment for the next year and who were not eligible for reassignment by CMS voluntarily switched PDPs for 2010 (Figures 6 and 7). The remaining 86 percent of this group stayed in their current plan and paid a monthly premium, despite being eligible for premium-free coverage through benchmark plans.5 A higher share (22 percent) of LIS enrollees not eligible for reassignment voluntarily switched plans in 2009, consistent with greater turnover in benchmark plan availability that year.6

Figure 6: The share of LIS enrollees changing plans for the 2010 plan year was driven by eligibility for reassignment and benchmark plan status

Figure 7: Among LIS enrollees who were not eligible for reassignment and whose PDPs were losing benchmark status, most did not voluntarily switch plans

All beneficiaries not eligible for reassignment in 2009 or 2010 received a notice from CMS (referred to as a “chooser notice”) at the start of the annual enrollment period. The notice informed them that they were subject to paying a monthly premium for Part D coverage in the coming year if they remained in their current plan and stated the amount instructions on how to make a switch and listed all the available premium-free plans in their region. Despite this information, most beneficiaries in this situation maintained enrollment in their current plans and thus paid a premium.

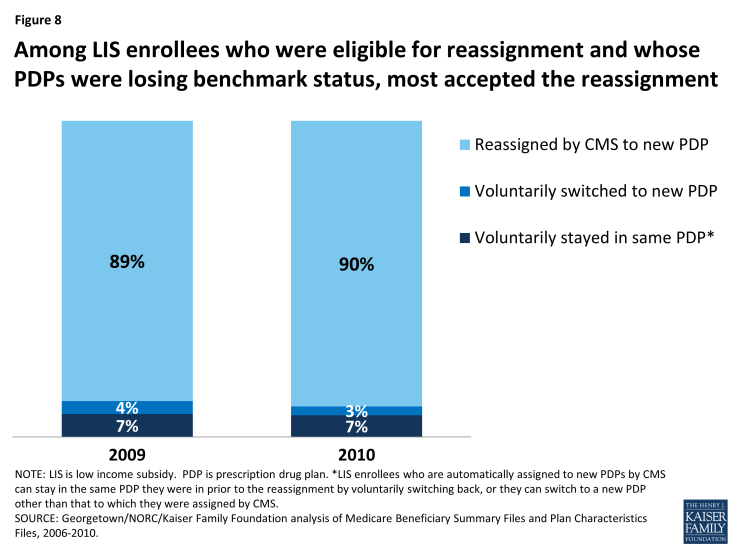

Among the subgroup of LIS beneficiaries who were eligible for reassignment by CMS and who were not slated to be in a benchmark plan in 2010 (about 1 in 6 LIS enrollees in PDPs), the vast majority (90 percent) accepted their reassignment by CMS to a new plan (Figures 6 and 8). These LIS enrollees received a notice from CMS at the start of the annual enrollment period informing them that they would be reassigned to a new PDP chosen randomly among eligible benchmark plans and of their right to pick a different plan to ensure the best coverage of the drugs they take. Accepting the reassigned plan means changing from one plan to another; doing so ensures that these LIS enrollees will maintain their premium-free PDP coverage but typically means a change in formulary. The Affordable Care Act added a requirement that CMS send a second letter in December identifying which of the individual’s drugs are covered under the plan to which the beneficiary has been assigned, with another reminder that they can still elect a different plan.

Figure 8: Among LIS enrollees who were eligible for reassignment and whose PDPs were losing benchmark status, most accepted the reassignment

About 10 percent of LIS enrollees who received a reassignment notice exercised their right to make a voluntary enrollment decision for 2010 rather than accept the reassignment by CMS to a new plan: 3 percent selected a new plan other than the one to which they were assigned by CMS and 7 percent chose proactively to stay in their current plan even though it was losing benchmark status and would require paying a premium.7 As a result of their voluntary enrollment decisions, these LIS enrollees lost their eligibility for reassignment to new plans in future years.

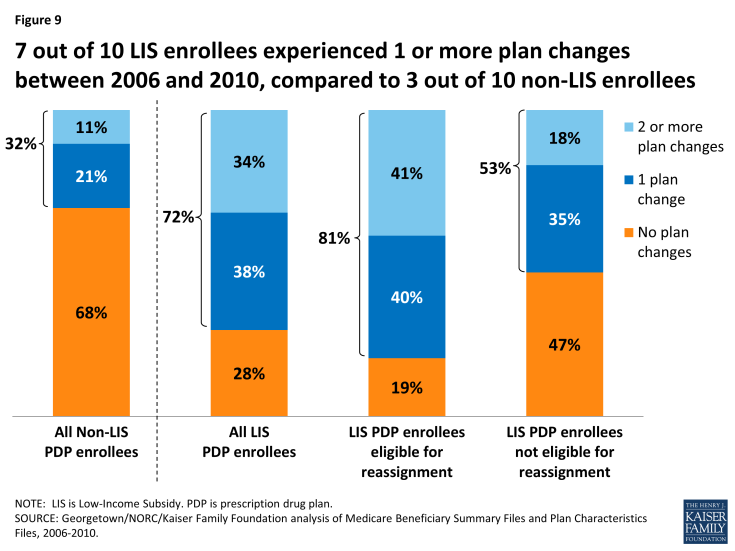

Nearly three-fourths of LIS beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in stand-alone PDPs changed plans (either voluntarily switched or were reassigned by CMS) at least once over the five years from 2006 to 2010. By contrast, only one-third of non-LIS enrollees voluntarily switched plans one or more times over the same period.

The 72 percent of LIS enrollees who changed PDPs at least once over the five-year period consists of 38 percent who experienced one plan change and 34 percent who had two or more plan changes (Figure 9).8 By contrast, far fewer (32 percent) non-LIS PDP enrollees made one or more voluntary plan switches between 2006 and 2010 (21 percent switched plans once and 11 percent switched plans two or more times).

Figure 9: 7 out of 10 LIS enrollees experienced 1 or more plan changes between 2006 and 2010, compared to 3 out of 10 non-LIS enrollees

Among LIS enrollees, a larger share of those who were eligible for reassignment experienced two or more plan changes between 2006 and 2010, compared to LIS enrollees who were not eligible for reassignment (41 percent versus 11 percent). This higher rate is because those LIS enrollees who are eligible for reassignment will be automatically assigned to a new plan whenever their current plan loses benchmark status. Yet, despite the year-to-year turnover in benchmark plan availability, the share of LIS beneficiaries who experienced frequent plan changes is relatively small—only 3 percent changed plans four or more times (that is, at least once a year between 2006 and 2010).

LIS beneficiaries who are not eligible for reassignment were also more likely than non-LIS beneficiaries to change plans at least once over a five-year period between 2006 and 2010 (53 percent versus 32 percent). One possible explanation for this higher rate is that these LIS enrollees received a notice from CMS during the annual enrollment period informing them that their premium would increase if they stayed in their current plan. The notice also informed them about their eligibility for other plans that were premium free. Non-LIS enrollees do not receive similar targeted information from CMS. Some may also have benefitted from state-based programs that helped them chose a new plan. And some may have taken advantage of their right to switch plans outside of the annual enrollment period.

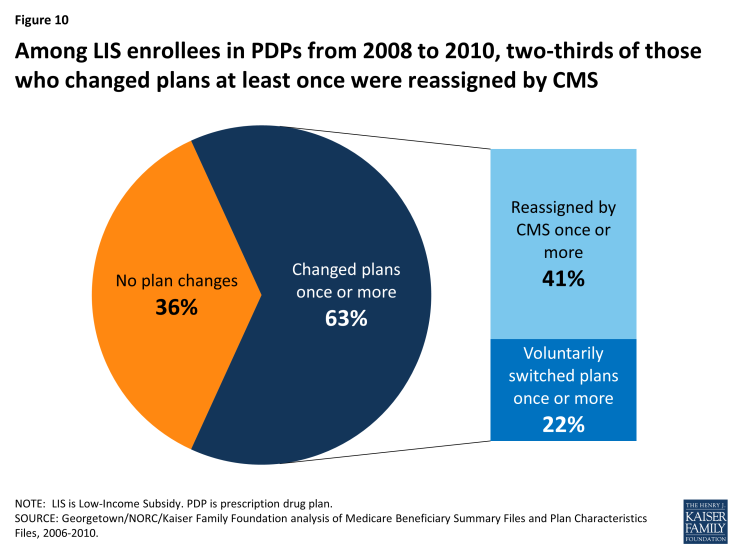

As was the case in any given year in our study period, reassignment by CMS was the main cause for plan changes among LIS enrollees continuously enrolled over a multiple-year period (Figure 10). The 63 percent of LIS beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in PDPs from 2008 to 2010 who also experienced a change in plans at least once across the three-year period consists of 41 percent who changed plans as a result of a reassignment by CMS and 22 percent who voluntarily switched to a new plan.9

Figure 10: Among LIS enrollees in PDPs from 2008 to 2010, two-thirds of those who changed plans at least once were reassigned by CMS

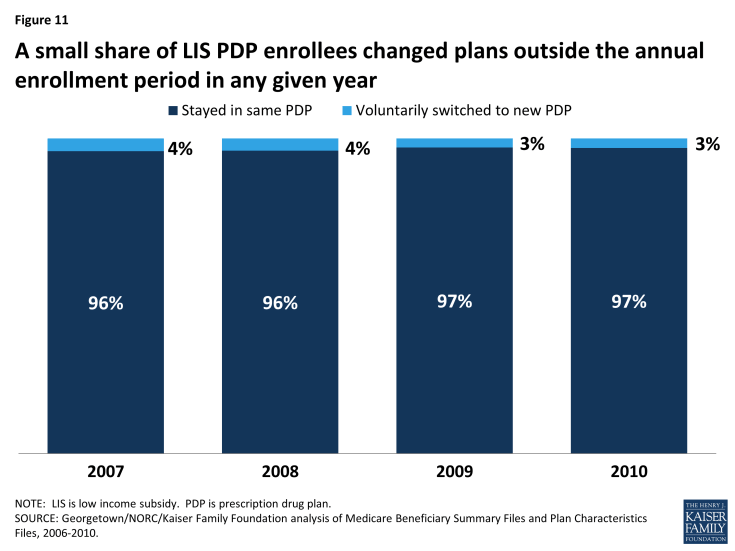

In any given year between 2007 and 2010, only a small share of LIS enrollees (no more than 4 percent) took advantage of their right to switch plans outside of the annual enrollment period.

Between February and December 2010, only 3 percent of LIS PDP enrollees switched to a different plan (Figure 11). All LIS beneficiaries have the right to switch plans at any time during the year, an option not available to non-LIS beneficiaries.10 But the average switching rate for LIS PDP enrollees outside the annual enrollment period was 0.3 percent per month, adding up to 3 percent to 4 percent of beneficiaries per year with a mid-year switch. LIS enrollees who were assigned to their current plan by CMS were less likely to switch to a different plan outside the annual enrollment period than those LIS enrollees who voluntarily selected their current plan.11 LIS beneficiaries were about twice as likely to switch plans in February and March, compared to later in the year. These higher switching rates most likely represent situations where beneficiaries responded to changes to either their plan assignments or plan features (such as formulary changes) that became effective in January after the annual enrollment period had ended. Although the rationale for these switches cannot be determined from administrative data, it is possible that beneficiaries encountered difficulties obtaining medications on their initial visits to the pharmacy after the plan changes were effective. In this case, some beneficiaries may find it easier to switch plans than to apply for a formulary exception or request a prior authorization.

Figure 11: A small share of LIS PDP enrollees changed plans outside the annual enrollment period in any given year

Over the period from mid-2006 to 2010, about 14 percent of continuously enrolled LIS PDP enrollees changed plans at least once outside the annual enrollment period. Although only a small share of LIS beneficiaries exercise their right to switch plans outside of the annual enrollment period in any one year, one in seven made such a switch at least once in a five-year period.12 Most of these beneficiaries had only a single plan change outside open enrollment between August 2006 and December 2010.13 The maximum number of plan switches outside the annual enrollment period by any LIS beneficiary in the sample was 10 switches.

After CMS sent a “nudge notice” in August 2010, about 5 percent of notice recipients changed plans. In June 2010, CMS mailed a notice to all LIS beneficiaries who were paying a premium advising them that other plan options were available for no premium. In August and September 2010, an estimated 36,000 beneficiaries (less than 0.5 percent of LIS beneficiaries, but about 5 percent of those receiving the notice) responded to this notice by switching plans, a rate modestly higher than in similar months.14 CMS repeated use of a reminder notice in May 2011, but did not send them in more recent years.

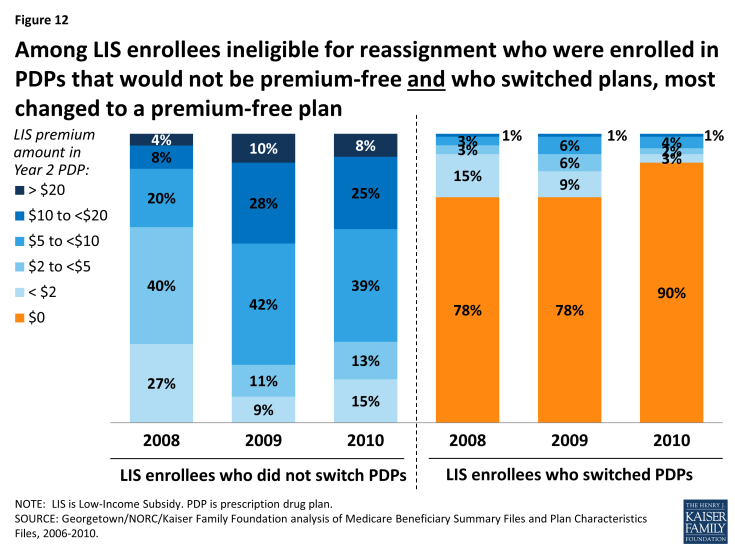

Among the relatively small share of LIS enrollees ineligible for reassignment who were in plans losing benchmark status and who voluntarily switched plans, a majority lowered their premiums by switching plans. Those LIS enrollees who are ineligible for reassignment and are enrolled in non-benchmark plans have been paying higher premiums over time.

Among the LIS enrollees who were both not eligible for reassignment and enrolled in PDPs that would not be premium-free in 2010, 90 percent of those who voluntarily switched PDPs chose a premium-free plan (Figure 12). Only 5 percent selected a plan with a monthly premium of at least $5. By contrast, 72 percent of LIS enrollees who were both not eligible for reassignment by CMS and who stayed in a non-benchmark plan paid premiums of at least $5 per month in 2010, and one-third paid premiums of $10 or more as a result of staying in their same plan and not switching to a premium-free benchmark plan. Our previous study showed that the relatively few non-LIS enrollees who switched plans between 2006 and 2010 were more likely than those who did not switch to end up in a plan that lowered their costs.15 But the LIS enrollees who switched plans saved themselves money more often than their non-LIS counterparts. Many in both groups would have saved money on premiums by changing plans more often.16 By contrast, LIS beneficiaries who are eligible for reassignment are almost always switched into a new plan when it would lower their premium costs.17

Figure 12: Among LIS enrollees ineligible for reassignment who were enrolled in PDPs that would not be premium-free and who switched plans, most changed to a premium-free plan

LIS enrollees who are not eligible for reassignment and who remain in non-benchmark plans have tended to pay increasingly higher premiums over time. The share of LIS beneficiaries in non-benchmark plans (eligible for but not receiving Part D coverage for no premium) paying at least $10 a month increased from 12 percent to 33 percent between 2008 and 2010, despite the fact that all of these LIS enrollees had at least one premium-free plan available to them in their area.

Discussion

All LIS Part D beneficiaries have the opportunity to switch plans voluntarily both during the annual enrollment period and at other times of the year. In addition, beneficiaries who were assigned to their current plans by CMS may be reassigned to a new plan if their plan no longer qualifies as premium-free. In any one year, most LIS beneficiaries do not change plans—but due to reassignments, plan changes are much more common among LIS beneficiaries than among non-LIS beneficiaries.

For those not eligible for reassignment by CMS, the switching rate for LIS enrollees is similar to that for non-LIS beneficiaries and for enrollees in other health insurance programs, such as the health benefits offered to federal employees or workers in private firms that offer a choice of plans.18 It varies from year to year, in line with turnover in benchmark plan availability.

The switching rate among LIS enrollees not eligible for reassignment by CMS is lower than the 29 percent switching rate for marketplace enrollees who used the national healthcare.gov system created under the Affordable Care Act.19 This is notable because marketplace enrollees who did not shop for new plans were automatically re-enrolled in the same plan, regardless of whether they would receive the maximum subsidy available to them. There was no process for automatic reassignment to new plans like that which is in place for some Part D enrollees.

The CMS policy for determining which LIS enrollees will be automatically reassigned attempts to balance the desire to ensure that LIS beneficiaries are not required to pay premiums and the desire to respect voluntary enrollment decisions made by some LIS beneficiaries. Reassignments by CMS have shielded many low-income beneficiaries from incurring premium costs for Part D coverage, but the policy has the consequence of reducing the financial protection available through the LIS program for the share of LIS enrollees who have chosen their own plans. As our analysis shows, these LIS enrollees are less likely to change plans and thus more likely to pay a premium than the other 3.9 million (58 percent) LIS enrollees who were eligible for reassignment to another plan by CMS for 2010.

Impact on Part D LIS Enrollees

There are two main consequences for Part D LIS enrollees who do not reexamine their plan choices on a regular basis: they may be missing an opportunity to avoid premiums, and they may be enrolled in a plan that does not offer optimal coverage for their drugs. Turnover in the availability of benchmark plans increases both the risk that an LIS enrollee not eligible for reassignment will pay a premium and the risk that an LIS enrollee who is reassigned to a new plan will end up in a plan that does not provide the optimal coverage for her drugs.

The data available for this study do not allow an analysis of why LIS beneficiaries shop for new plans, only whether they actually elect to change plans. Possible reasons for not shopping include a preference for the status quo even if it means modestly higher costs, a concern that shopping for a plan is confusing and difficult, and a lack of awareness that switching could result in lower costs.20 Those who do compare their plan options still may not switch plans because their current plan best meets their needs even if it has a premium (based on the match between plan formularies and current drug needs), because they find available resources are inadequate for assessing plan differences, or they prefer not to “rock the boat.”

LIS Enrollees Not Eligible for Reassignment

The CMS approach to reassignment reduces the number of LIS beneficiaries who pay premiums, but the rules about qualifying for reassignment exclude those who voluntarily chose their current plan. The latter includes not only LIS enrollees who made a choice on their own but also those who chose their current plan on the advice of a counselor, a state pharmacy assistance program, or some other helper—help that may have occurred years earlier. To the extent that such assistance may no longer be available to these enrollees, CMS could consider helping a larger share of those now regarded as ineligible for reassignment.

Many LIS beneficiaries who are not eligible for reassignment by CMS are in plans that are not premium-free for LIS enrollees, meaning they are missing an opportunity to save money. In 2014, LIS beneficiaries not in premium-free plans paid an average of $17.85 per month in premiums, and 13 percent of those paying a premium paid more than $25 per month.21 Some LIS beneficiaries, however, may be choosing to pay a premium to get more of their drugs on formulary or fewer formulary restrictions. Administrative data do not allow us to determine whether these enrollees are in fact examining their options and making a deliberate choice to pay premiums, but it seems likely that many are not shopping on a regular basis—similar, in fact, to behavior among non-LIS enrollees. The CMS “chooser notices” do not appear to be inducing many of those who are scheduled to pay a premium to switch plans. While beneficiaries who get notices about their upcoming premium increase are more likely than non-LIS beneficiaries to change plans, most of those getting these notices do not make a change of plans. CMS may want to evaluate whether there are better ways to encourage shopping or to nudge enrollees into changing plans when appropriate, although one CMS test of a nudge notice failed to generate much response.

Our analysis finds that most LIS beneficiaries who voluntarily switched plans selected a plan with no premium. Other factors may have influenced their decisions as well, including the drugs available on plan formularies, restrictions on filling prescriptions such as prior authorization, availability of pharmacies in plan networks,22 plan quality ratings, or the general reputation of plans. Since cost sharing for LIS beneficiaries is by statute the same for all plans, out-of-pocket drug costs do not vary based on tier placement or whether a pharmacy offers preferred cost sharing but only if drugs are excluded from plan formularies.

LIS Enrollees Eligible for Reassignment

The circumstances are quite different for LIS beneficiaries who are eligible for reassignment, who represent a majority of all LIS beneficiaries. Depending on the year, CMS has reassigned between 500,000 and 2 million LIS beneficiaries to new plans to maintain their enrollment in premium-free plans. Between 2006 and 2010, most of these LIS enrollees accepted their reassignment. Although it is possible for some LIS beneficiaries to be reassigned to new plans from year to year, there has been less overall churning than might have been expected based on the number of plans that have lost benchmark status every year. According to our analysis, although 41 percent of LIS enrollees were reassigned two times out of the four enrollment periods between 2006 and 2010, only 3 percent were reassigned for four years in a row.

CMS makes reassignments to new plans on a random basis among available benchmark plans, a process which does not incorporate available information on enrollees’ use of drugs and pharmacies. Although this analysis did not consider which plan best meets a beneficiary’s needs, other work suggests that a system of beneficiary-centered assignment, including options of making assignments to enhanced plans with low premiums, could lower costs for beneficiaries and even for the government.23

Turnover in Benchmark Plan Availability

Our findings show that more beneficiaries change plans in years where there is greater turnover in the availability of benchmark plans. Although these changes usually lower overall costs for beneficiaries, there is also the potential for disruption resulting from different formularies, coverage restrictions, and administrative procedures. In recent years, CMS has adopted policies to reduce the annual turnover in benchmark plan availability. For example, the Affordable Care Act gave CMS the authority to allow LIS beneficiaries to remain in plans that miss benchmark status by a de minimis amount (usually $2 or less) without paying a premium—a policy that was tested on a demonstration basis in 2007 and 2008. In 2007, for example, one-fourth of all benchmark plans achieved that status through the de minimis policy. As a result, fewer reassignments were required. Other policies could increase the availability of benchmark plans, such as allowing LIS beneficiaries to enroll without a premium in enhanced plans that are below the benchmark.24

Lessons for the ACA

Subsidy-eligible marketplace enrollees are in a situation that partially resembles LIS enrollees, in that the value of their subsidy is maximized by enrolling in one of the lower-cost silver plans (similar to benchmark plans in LIS). In 2015, 29 percent of renewing marketplace enrollees switched plans on the federally facilitated marketplace, a substantially larger voluntary switching rate than among Part D LIS enrollees in the years we studied.25 Results varied in some of the state-based marketplaces. In Covered California, where premiums were relatively stable, only 6 percent of renewing enrollees switched plans,26 whereas 62 percent changed plans in HealthSource Rhode Island, where automatic renewal was not an option for consumers.27

Consumers who receive marketplace subsidies have higher incomes (always above 138 percent of the federal poverty line or FPL) than Part D LIS beneficiaries, nearly all of whom have incomes below 150 percent of FPL.28 However, the potential dollars at stake for consumers in the marketplaces tend to be much greater, since overall premiums for marketplace plans are much larger than premiums for stand-alone PDPs. Thus, the financial consequences of paying a premium could be greater for Part D LIS beneficiaries when considering premium payments as a share of income. Also, plan differences may matter more to marketplace enrollees. For example, plan networks may affect their relationships with all of their health care providers, not only pharmacies. And those who shop may find that marketplace plan networks are narrower overall than Part D pharmacy networks or Part D plan formularies, so that the risk of a poor match is greater.

The federally-facilitated marketplace and most state-based marketplaces implemented an automatic re-enrollment process for 2015 that allowed most people with coverage in 2014 to maintain that coverage in 2015, but the automatic renewal process did not necessarily obtain the coverage that maximized the value of the enrollees’ subsidy.29 In particular, the automatic renewal did not take into account the changes in premiums, and did not offer enrollees any equivalent of the Part D method for reassigning some beneficiaries to new plans. CMS issued a proposed rule that outlined some alternative approaches for the future, including the possibility of reassignments by the marketplaces. For reasons noted above, reassignment raises a more complex set of issues for plans that provide a full set of benefits than for plans that are limited to prescription drug coverage. Although CMS chose not to pursue this approach in its final rule, the agency indicated that it would welcome efforts by states to test such approaches. The experience of Part D LIS enrollees may offer insights into these options for the marketplaces, and the marketplace might offer some lessons for Part D.

The authors thank Christopher Powers at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for invaluable assistance with data acquisition.