The Uninsured at the Starting Line in California: California findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA

III. Gaining Coverage, Getting Care

How New Insurance Coverage Could Change How Californians Use Health Care

Uninsured adults in California generally do not seek or receive health care services at the same rate as insured adults, even when they have a need for care. Many uninsured adults have substantial health care needs that are not monitored by a physician. Cost is the main reason uninsured Californians do not receive care when needed, and many lack a regular provider to facilitate follow-up or ongoing care. When uninsured adults do receive care, they often have limited options. As coverage expands under the ACA, uninsured adults are likely to get care more frequently and establish relationships with providers. Patterns of care may shift, and providers may see an increase in patients who may have previously untreated or undiagnosed health care problems.

A large segment of the uninsured in California has little or no connection to the health care system.

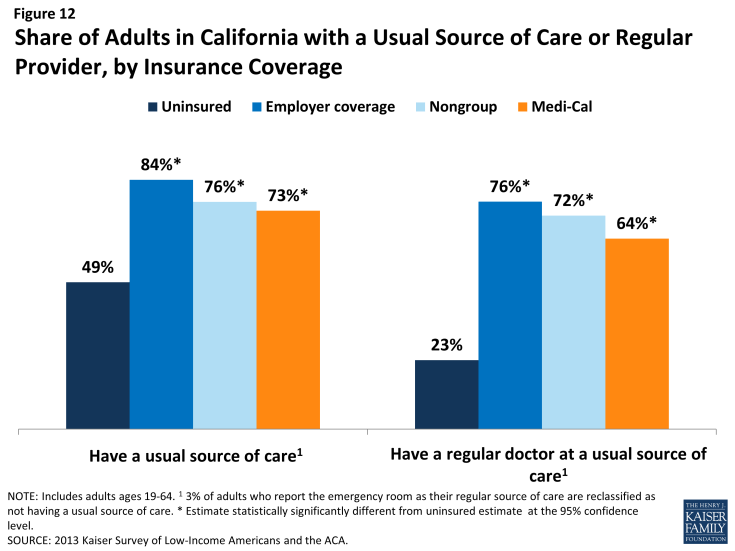

While some uninsured adults in California did report receiving health care services, most reported few connections to the health care system. Only about half of uninsured adults in California (49%) report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room). Having a usual source of care is an indicator of being linked in to the health care system and having regular access to services. In comparison, nearly all insured adults in California —84% of those with employer coverage, 76% of those with nongroup coverage, and 73% of those with Medi-Cal coverage— have a usual source of care (Figure 12). In addition, uninsured adults in California are less likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care, with only about one-quarter (23%) of uninsured adults reported having a regular doctor, about one third the rate of insured adults. Notably, low-income uninsured adults in California are the least likely to have a usual source of care or a regular physician (Table 3).

Figure 12: Share of Adults in California with a Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Insurance Coverage

| Table 3: Share of Adults in California with Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medi-Cal | |||

| Has a usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 49% | 84%* | 76%* | 73%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| ≤138% FPL | 50% | 64%* | — | 74%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 50% | 81%* | 76%* | 71%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 89% | 76% | — | |

| Has a regular provider at usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 23% | 76% | 72% | 64% | |

| By Income | |||||

| ≤138% FPL | 21% | 47%* | — | 65%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 25% | 75%* | 69% | 61%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 82% | 73% | — | |

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or unweighted cell sizes below 30 are not provided. ^ 3% of adults who report the emergency room as their regular source of care are reclassified as not having a usual source of care. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs.*Estimate is statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

|||||

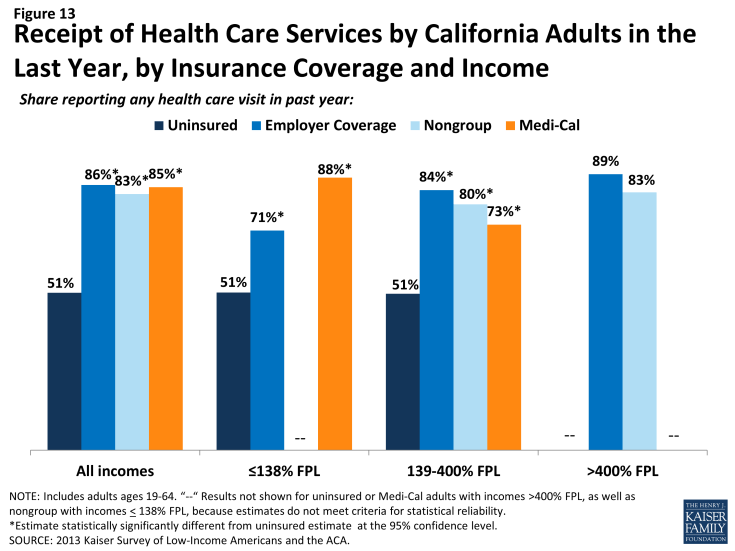

This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults in California to go without care. Nearly half of uninsured adults in California (49%) reported no health care visits—including hospital visits, doctor’s office or clinic visits, mental health services, or trips to the emergency room— in the past year, compared to 15% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries and 14% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 13). This pattern holds across all income groups. Of particular concern is the lack of preventive visits among uninsured Californians. One third (33%) of uninsured adults reported a preventive visit with a physician in the last year, compared to 75% of adults with employer coverage and 62% of adults with Medi-Cal (data not shown).

Figure 13: Receipt of Health Care Services by California Adults in the Last Year, by Insurance Coverage and Income

The survey findings reinforce conclusions based on prior research: having health insurance affects the way that people interact with the health care system, and people without insurance have poorer access to services than those with coverage.1,2,3 Thus, gaining coverage is likely to connect many currently uninsured adults in California to the health care system. However, outreach may be needed to link the newly-insured to a regular provider and help them establish a pattern of regular preventive care. In addition, resources may be needed to reach out to the remaining uninsured in California—including undocumented immigrants who are ineligible for coverage expansions—to link them to the health care system and help them obtain preventive and acute health care services.

Many uninsured Californians have health needs, many of which are unmet or are being met with difficulty.

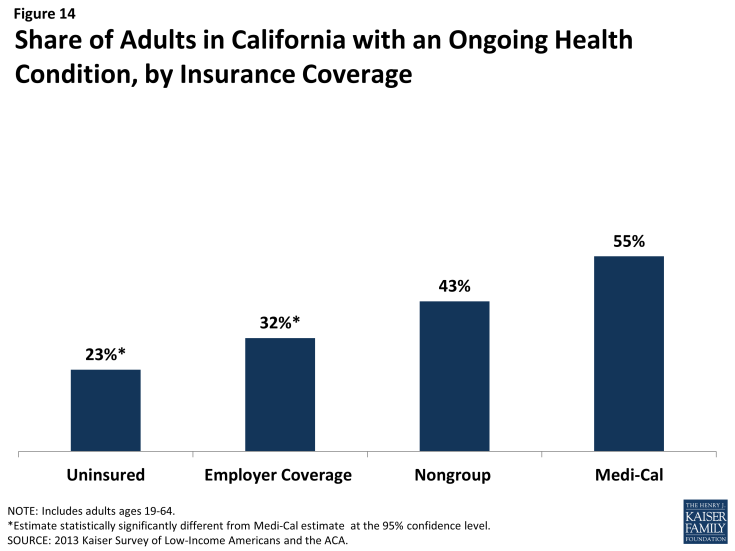

Californians who lack health insurance still have health care needs. Nearly one-quarter (23%) of uninsured adults reported an ongoing health condition, compared to 32% with employer coverage and 55% with Medi-Cal (Figure 14). The lower percent of uninsured adults reporting an ongoing health condition, compared to those with insurance, may reflect lower rates of disease detection among this group due to their lack of access to primary and preventative care.4 In contrast, Medi-Cal beneficiaries are most likely to report having an ongoing health condition, which reflects Medi-Cal’s role in caring for people with substantial health needs, such as individuals with disabilities or people who become impoverished due to high health care expenses. These findings hold across income groups (Table 4). As low-income uninsured gain coverage under reform, Medi-Cal’s role will expand to include a broader scope of the adult population.

| Table 4: Health Status of California Adults, by Income and Coverage | ||||||

| Uninsured | Insured | |||||

| Employer Coverage | Nongroup | Medi-Cal | ||||

| Fair or Poor Overall Health | All | 33% | 10%* | 19%* | 49%* | |

| By Income | ||||||

| ≤138% FPL | 38% | 16%* | — | 53%* | ||

| 139-400% FPL | 30% | 16%* | — | — | ||

| >400% FPL | — | 7% | — | — | ||

| Fair or Poor Mental Health | All | 15% | 6%* | — | 32%* | |

| By Income | ||||||

| ≤138% FPL | 18% | — | — | 32% | ||

| 139-400% FPL | 12% | 6% | — | — | ||

| >400% FPL | — | — | — | — | ||

| Have ongoing health condition that needs to be monitored regularly or needs regular care | All | 23% | 32%* | 43% | 55%* | |

| By Income | ||||||

| ≤138% FPL | 23% | 21% | — | 58%* | ||

| 139-400% FPL | 21% | 26% | 49%* | 47%* | ||

| >400% FPL | — | 37% | — | — | ||

| Take prescription medication on regular basis^ | All | 20% | 38% | 49% | 58% | |

| By Income | ||||||

| ≤138% FPL | 20% | 23% | — | 60% | ||

| 139-400% FPL | 16% | 32% | 48% | 52% | ||

| >400% FPL | — | 44% | — | — | ||

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or unweighted cell sizes below 30 are not provided.^ Excludes birth control. *Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||||

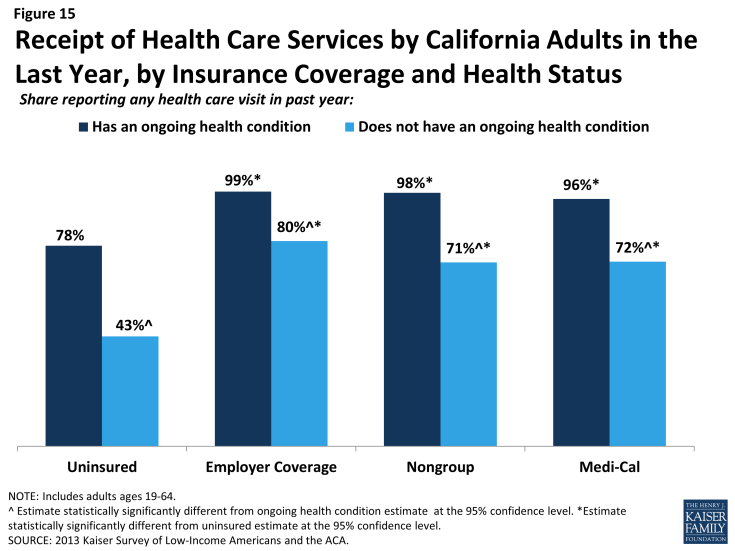

While uninsured Californians with an ongoing health condition are more likely than those without to report receiving services (Figure 15), they are still less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care. While less than half (43%) of uninsured adults without an ongoing health condition say they received health care services in the last year, more than three-quarters (78%) of uninsured adults with a health condition received health care services. However, this rate is still lower than adults who have a health condition and have employer coverage, nongroup coverage, or Medi-Cal, nearly all of whom (99%, 98%, and 96%, respectively) reported receiving medical services over the course of the year.

Figure 15: Receipt of Health Care Services by California Adults in the Last Year, by Insurance Coverage and Health Status

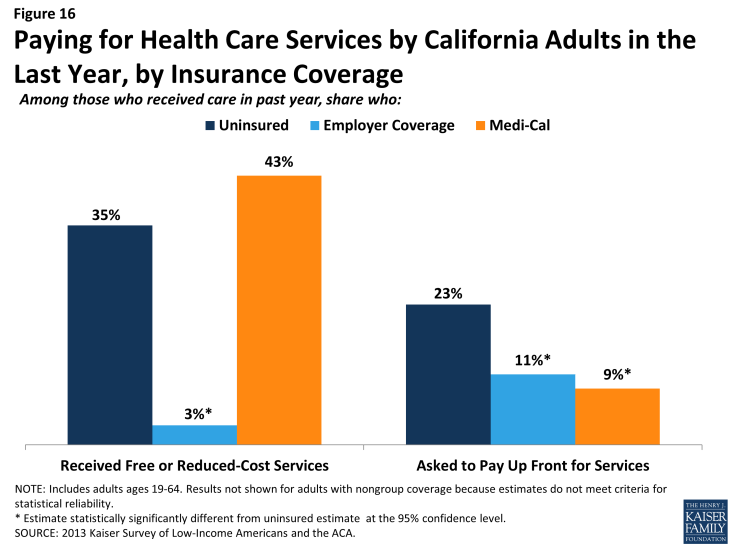

When uninsured Californians do receive care, they sometimes receive free or reduced-cost care, though the majority does not. Among adults in California who reported that they received a health care service in the past year, 35% of uninsured adults in California reported receiving free or reduced cost care, versus just 3% of those with employer coverage (Figure 16). Notably, 43% of adults with Medi-Cal who received services reported that they received free or reduced cost care. They may have done so during a period of uninsurance in the previous year or may associate the fact that they pay little or no costs when they see a provider as receiving “free or reduced cost” care. Uninsured adults in California who received care were much more likely than their insured counterparts to be asked to pay up front for care: almost one-quarter (23%) reported being asked to pay for the full cost of medical care (not counting copayments) before they could see the doctor or provider, compared to just 11% of those with employer coverage and 9% of adults with Medi-Cal. Again, adults with employer coverage or Medi-Cal may have experienced these issues during a period in the past year when they lacked coverage or when using a service not covered by their insurance.

Figure 16: Paying for Health Care Services by California Adults in the Last Year, by Insurance Coverage

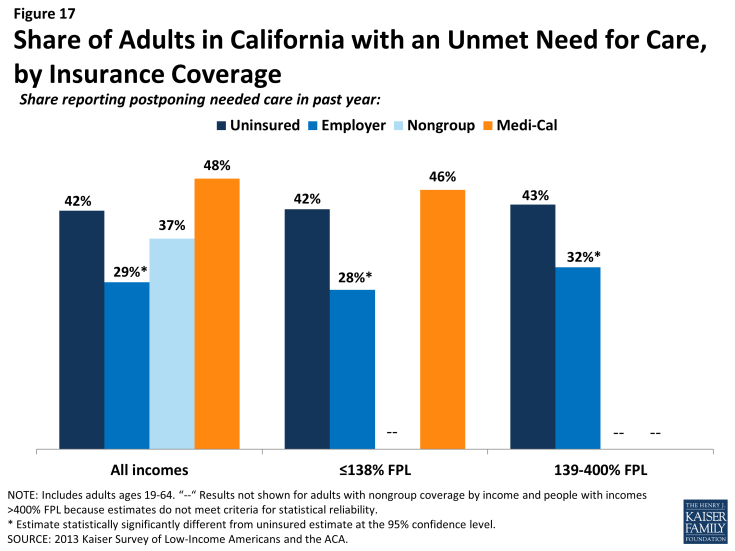

Although some uninsured and insured adults in California reported receiving free or reduced cost health care services, a larger share reported an unmet need for care. More than four in ten (42%) of the uninsured and almost half (48%) of Medi-Cal beneficiaries in California reported needing but postponing care, compared to 29% of adults with employer coverage, and this pattern holds across income groups (Figure 17). The relatively high rate among Medicaid beneficiaries reflects higher need: when examining rates for only people without an ongoing health condition, uninsured adults reported the highest rates of unmet need and Medi-Cal adults reported rates similar to people with other coverage (data not shown).

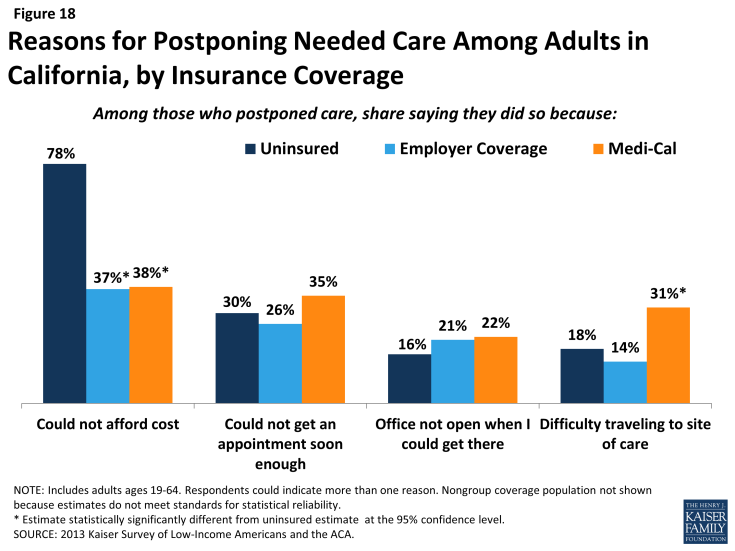

The most common reason for postponing care among uninsured Californians is cost (78%). Adults with employer coverage (37%) or Medi-Cal (38%) are less likely to report cost as a reason for postponing care because presumably their insurance pays most or all of that cost (Figure 18). However, adults with Medi-Cal were more likely than other adults to report that they postponed care because they had difficulty traveling to the doctor’s office or clinic. These issues may reflect problems with provider participation in Medicaid, limits on Medicaid coverage of transportation services, or transportation barriers unique to the low-income population (such as not having a car). Low-income adults may also experience access challenges due to difficulty getting time off from work or obtaining childcare for the time when they are at the provider.

Given the health profile of currently uninsured adults in California, there is likely to be some pent-up demand for health care services among the newly-covered. Health systems may see increases in adults seeking care and will need to prepare for the newly insured. As people gain coverage under the ACA, the cost barriers to health care services will be reduced, but other barriers such as transportation or wait times for appointments may remain. Cuts to Medi-Cal payment rates, on top of already low rates and low provider participation, may pose a challenge for newly-insured low-income individuals’ ability to find a provider to treat them.5,6 In addition, it is important to bear in mind continuing access barriers among the population that remains uninsured under the ACA. As resources and attention shift to the newly-insured population, individuals left out of coverage expansions (such as undocumented immigrants) will continue to have health needs. The ACA included funds to expand service capacity in medically underserved areas, including expansion of community health centers, nurse-managed health centers, and school-based clinics. To meet the health care needs of both insured and uninsured individuals, it is important that these systems develop flexible treatment times and new models of care to accommodate people’s availability and expand capacity in areas where low-income individuals reside or seek care.

Many uninsured Californians reported limited options for receiving health care when they need it.

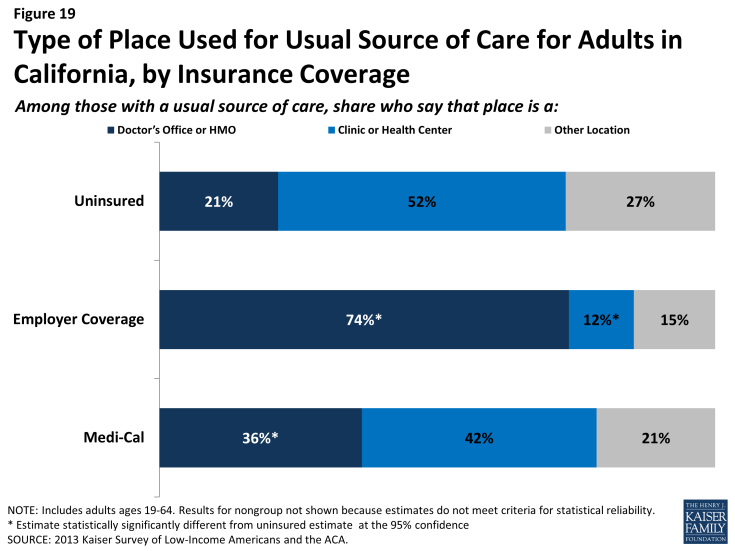

Uninsured adults in California are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care in a private physician’s office. Only two in ten (21%) uninsured California adults who have a regular source of care reported that it is a physician’s office or HMO, compared to nearly three-quarters (74%) of adults with employer coverage and more than one third with Medi-Cal (36%)(Figure 19). Over half (52%) of uninsured adults in California who have a regular source of care reported clinics or health centers as their usual source of care, four times as high as adults with employer coverage (12%). Notably, 9% of uninsured adults in California reported the emergency room as their usual source of care – substantially higher than any other group, but lower than the rate for uninsured adults nationwide (data not shown).7

Figure 19: Type of Place Used for Usual Source of Care for Adults in California, by Insurance Coverage

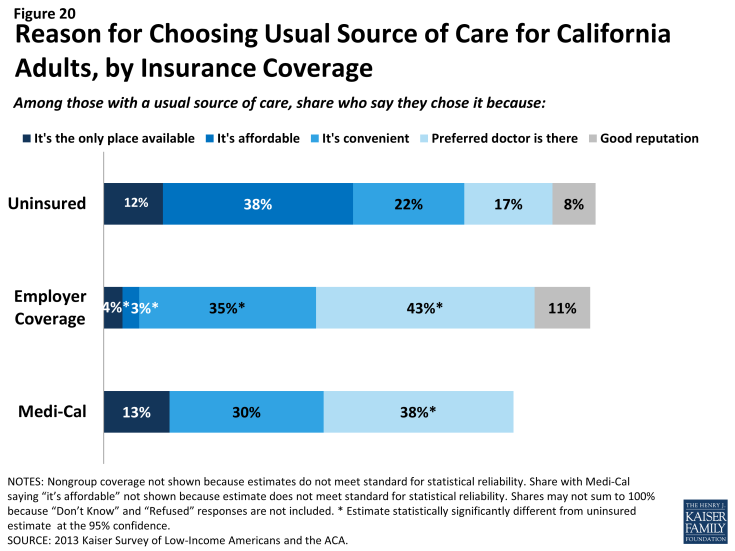

Uninsured and Medi-Cal adults in California are more likely than other adults to reported that they have limited options for their usual source of care. Among people with a usual source of care, 12% of the uninsured and 13% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries reported that they chose their usual source of care because it is the only option available to them, compared to 4% with employer coverage (Figure 20). Compared to adults with employer coverage, uninsured adults in California are also more likely to choose their usual source of care because it’s affordable and less likely to choose their site of care because of convenience. Both Medi-Cal adults and adults with employer coverage are more likely to choose a site of care based on the ability to see their preferred provider. Most of those who say they chose their usual source of care based on cost chose to go to a clinic or health center, reflecting the fact that these providers often have a mission to serve low-income populations and offer services with sliding scale fees.8

Based on the experience of their insured counterparts, the uninsured in California may have more options for where to receive their care once they obtain coverage under the ACA. Specifically, as people gain insurance coverage, they may be less likely than those without coverage to choose a usual provider based on cost; thus, they may feel they have more options for where to receive their care. For adults covered by Medi-Cal, clinics and health centers are a leading source of care. These providers already see a large share of uninsured adults and may play an important role in serving this population even once they gain insurance. They will also continue to serve an important role in caring for the remaining uninsured population. Many of these providers offer services at reduced or sliding scale cost and will be the only option for people who have no insurance to help cover the cost of their care.

However, consumer preferences for site of care function against a backdrop of policy decisions that affect provider participation and capacity. For example, clinics and health centers’ ongoing role in serving the uninsured population—and people’s continuity of treatment— will depend in part on whether they are included in plan networks under both Medi-Cal and Covered California plans. Further, many Medi-Cal providers throughout the state are starting to face a 10% provider rate cut, and it will be important to monitor whether this provider rate cut negatively affects private provider participation in Medi-Cal and beneficiaries’ ability to see providers in this setting if they choose. It will also be important to evaluate whether efforts to expand capacity for primary and specialty services among safety net hospitals participating in DSRIP affects capacity and sites of care available to new and existing Medi-Cal beneficiaries.

Last, some Californians who have relied on emergency rooms or urgent care centers as their usual source of care may require help in establishing new patterns of care and navigating the primary care system. However, it may be possible to change health care usage patterns over time. A study of Health Care Coverage Initiative enrollees who were enrolled in a medical home from September 2007 to August 2010 found that, although emergency department usage increased initially, both emergency room visits and hospitalizations decreased over the three year study period, while primary care visits increased significantly.9