The Uninsured at the Starting Line: Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA

Background: The Challenge of Gaining Insurance Coverage Prior to the ACA

Prior to implementation of the ACA, over 47 million Americans—nearly 18% of the population—were without health insurance coverage. Because publicly-financed coverage has been expanded to most low-income children and Medicare covers nearly all of the elderly, the vast majority of uninsured people are nonelderly adults.1 Not having health insurance has well-documented adverse effects on people’s use of health care, health status, and mortality, as the uninsured are more likely to delay or forgo needed care leading to more severe health problems.2 Lack of insurance coverage also has implications for people’s personal finances, providers’ revenue streams, and system-wide financing.3,4,5 The coverage provisions in the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to address these issues by making coverage more available and affordable, particularly for people with low or moderate incomes.

The main barrier that people have faced in obtaining health insurance coverage is cost: health coverage is expensive, and few people can afford to buy it on their own. While most Americans traditionally obtain health insurance coverage as a fringe benefit through an employer, not all workers are offered employer coverage, and not all adults are working. Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) cover many low-income children, but eligibility for parents and adults without dependent children is limited, leaving many adults without affordable coverage.

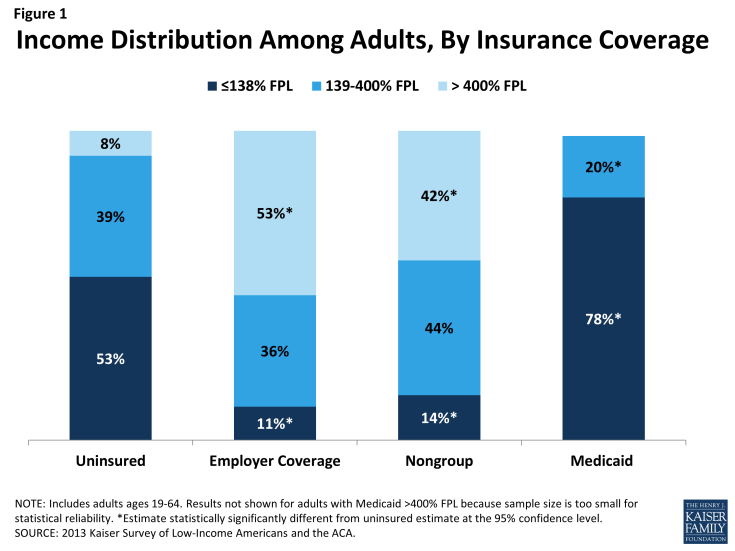

These barriers to coverage are reflected in the characteristics of the uninsured population. Compared to those with private coverage, uninsured adults are more likely to be low-income (Figure 1). A majority of uninsured adults (53%) are low-income, or have incomes at or below 138% FPL, in contrast to 11% of adults with employer coverage and 14% of adults with nongroup. Adults with Medicaid are the most likely of any coverage group to be low-income, reflecting the fact that prior to the ACA, adult income eligibility limits were generally very low (often below half the poverty level). Less than one in ten uninsured adults have incomes greater than 400% FPL, compared to over half of adults with employer coverage (53%) and 42% of adults with nongroup coverage.

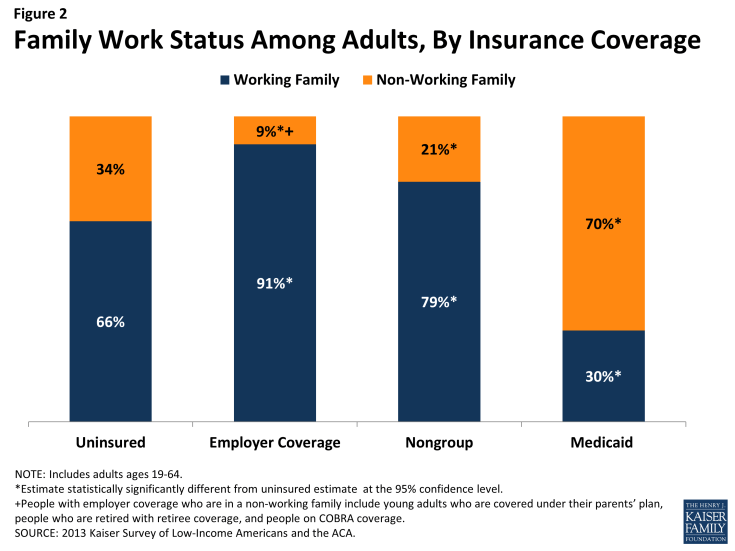

Corresponding to their lower incomes, uninsured adults are less likely than privately insured adults to be in a working family; however, the majority of uninsured adults are in a family with either a full- or part-time worker. About two-thirds (66%) of uninsured adults are in a working family (that is, either they, or their spouse if they are married, report working either full or part-time), in contrast to 91% of adults with employer coverage and 79% of adults with nongroup coverage (Figure 2). Adults with Medicaid are the least likely to be in a working family (30%), again reflecting very low income eligibility limits for adults prior to the ACA.

Uninsured adults also differ from insured adults with regards to other demographic characteristics. Uninsured adults are likely to be younger than insured adults, as younger adults have lower incomes and looser ties to employment than older adults. Two-thirds (67%) of uninsured adults are ages 19-44 as compared to 56% of adults with employer coverage or Medicaid and 41% of adults with nongroup coverage (Appendix Table A1).

There also are significant racial and ethnic differences in health coverage among nonelderly adults. For example, uninsured adults are more likely to be Hispanic – 30% of uninsured adults are Hispanic – than adults with employer coverage (11%), nongroup coverage (9%), or Medicaid (18%). About half (49%) of uninsured adults are White, non-Hispanic, compared to 75% of adults with nongroup coverage, and 70% of adults with employer sponsored insurance. Racial and ethnic differences in coverage rates, which are reflective of differences in income and work status by race/ethnicity, have implications for efforts to address health care disparities. Also, about one in five uninsured adults is a noncitizen (19%), compared to less than 7% of adults with Medicaid or employer coverage. Citizenship status may leave many uninsured adults ineligible for Medicaid, increasing the likelihood they will remain uninsured.

Among the primary goals of the ACA were filling in gaps in the availability of public coverage by expanding Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults and making private coverage more affordable for moderate-income adults who lack access to coverage through a job. The ACA also aims to simplify and coordinate eligibility and enrollment across programs, ensure coverage for a basic package of health benefits, and facilitate innovations in service delivery. As policymakers embark on early implementation of the law, it is important to remember who the ACA aims to help and how their characteristics may inform efforts to reach them.