The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer - Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured amidst Changes to the Affordable Care Act

How have health insurance coverage options and availability changed under the ACA?

In the past, gaps in the public insurance system and lack of access to affordable private coverage left millions without health insurance. The ACA filled in many of these gaps and provided new coverage options. Under the ACA, as of 2014, Medicaid coverage has been expanded to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138% of poverty in states that have adopted the expansion, and tax credits are available for people with incomes up to 400% of poverty who purchase coverage through a health insurance marketplace. These new coverage options have increased access to health insurance and health care for millions, but recent actions may affect coverage options and people’s likelihood of signing up for or retaining ACA coverage.

ACA Coverage Provisions

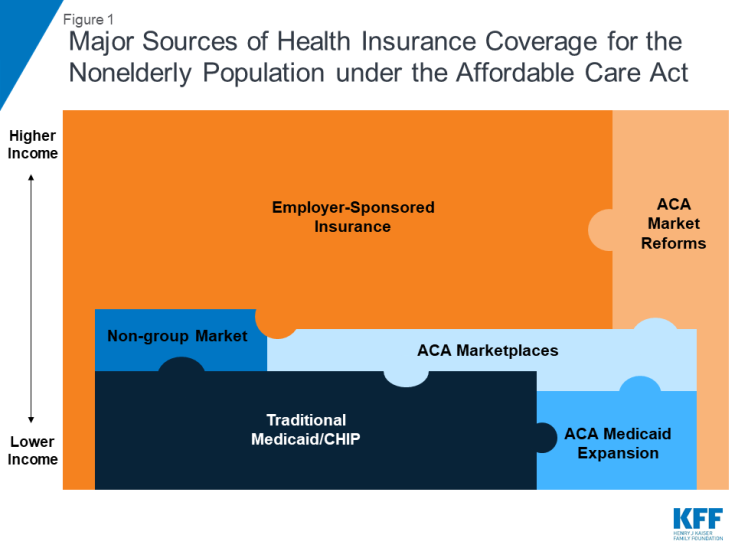

The ACA’s coverage provisions built on and attempted to fill gaps in a piecemeal insurance system that historically left many without affordable coverage. In the past, many people did not have access to affordable private coverage or were ineligible for public coverage. Poor and low-income adults were particularly likely to lack coverage, and the main reason that most people said they lacked coverage was inability to afford the cost.1 The ACA aimed to provide coverage options across the income spectrum by filling in gaps in eligibility for public coverage, access to employer coverage, and availability of affordable non-group coverage (Figure 1).2

Figure 1: Major Sources of Health Insurance Coverage for the Nonelderly Population under the Affordable Care Act

The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to low-income adults, eliminating categorical restrictions on coverage in states that have expanded their programs. Medicaid and CHIP have long been important sources of coverage for low-income children and people with disabilities, but in the past, coverage for parents was limited to those with very low incomes (often below 50% of the poverty level), and adults without dependent children—regardless of how poor—were ineligible.3 The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to nearly all adults with income at or below 138% of poverty. The 2012 Supreme Court ruling effectively made the expansion a state option. As of January 2019, 37 states, including DC, had adopted Medicaid expansion under the ACA,4 and over 12 million people were covered through the ACA Medicaid expansion.5

The ACA established health insurance marketplaces where individuals and small employers can purchase non-group insurance, often with a subsidy. Very few people were covered by non-group health insurance policies prior to the ACA, as such policies could be prohibitively expensive or restrictive.6 Under the ACA, health insurance marketplaces where individuals can shop for health coverage operate in each state.7 To make coverage purchased in these new marketplaces affordable, the federal government provides tax credits for people with incomes between 100% and 400% of poverty. Tax credits are available on a sliding scale based on income and limit premium costs to a share of income. In addition, ACA allows for cost-sharing subsidies to reduce what people with incomes between 100% and 250% of poverty have to pay out-of-pocket to access health services. In 2018, more than 10 million people enrolled in marketplace plans, and the vast majority received financial assistance with their coverage.8 A small number of people still purchase non-group coverage outside the marketplace.9

The ACA includes provisions to promote employer-based coverage. The availability and affordability of employer-sponsored coverage has declined over time. From 2008 to 2013, the share of firms that offered workers health benefits declined from 63% to 57%, and health insurance premium increases outpaced growth in workers’ earnings and overall inflation.10 Under the ACA, large and medium-size employers (those with 50 or more full-time equivalent employees) are assessed a fee per full-time employee (up to $2,320 in 2018) if they do not offer affordable coverage and have at least one employee who receives a marketplace premium tax credit. To avoid penalties, employers must offer insurance that pays for at least 60% of covered health care expenses, and the employee’s share of the individual premium must not exceed a set share of family income (9.86% in 2019).11, 12 In addition, the ACA established the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) marketplace to help small employers and their workers access affordable health coverage.13 Offer, eligibility, and take-up rates of employer-sponsored insurance have largely stabilized since 2013,14 and employer coverage remains the largest source of health coverage for the nonelderly (covering 153 million people in 2017).15

The ACA also extends dependent coverage in the private market. In the past, young adults (age 19-26) were at particularly high risk of being uninsured, largely due to their low incomes and difficulty affording coverage. As of 2010, young adults may remain on their parents’ private plans (including non-group and employer-based plans) until age 26. This provision led to drastic decline in the young adult uninsured rate from 32% in 2010 to 14% in 2017.16

The ACA included nationwide insurance regulations to improve access to coverage for those who may have been previously denied coverage and set new requirements for benefits and cost sharing in ACA plans. Prior to the ACA, in many states, premiums in the non-group market could vary by age or health status, and people with health problems or at risk for health problems could be charged high rates, offered only limited coverage, or denied coverage altogether. The ACA included new rules for insurers prevent them from denying coverage to people for any reason, including their health status, and from charging people who are sick more (though insurers can, within limits, still charge older people more for coverage). In addition, the ACA established a minimum “essential health benefits” package for marketplace plans, Medicaid expansion enrollees, and some employer plans.

Under the ACA, almost all people were required to have health insurance coverage or be subject to a tax penalty. This requirement was intended to encourage healthier individuals to purchase coverage through the marketplace. The requirement only applied to those with access to affordable coverage, defined as costing no more than 8% of an individual’s or family’s income (certain other exemptions to the mandate also were granted). The penalty from 2016 to 2018 was assessed as 2.5 percent of family income, with both a minimum and maximum.17

Coverage for immigrants remains limited under the ACA. Lawfully-present immigrants can receive coverage through the ACA marketplaces, but they continue to face eligibility restrictions in Medicaid that have been in place since prior to the ACA. Specifically, many lawfully present non-citizens who would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid remain subject to a five-year waiting period before they may enroll.18 Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid and are prohibited from purchasing coverage through a marketplace or receiving tax credits.

Changes to the ACA under the Trump Administration

With the change in Administration in January 2017, there was renewed debate over the future of the ACA. Discussion of ACA repeal and public comments from President Trump declaring the law to be “dead” and “finished,”19 led some people to be confused about whether the law remained in effect.20 In addition, reduced funding for outreach and enrollment assistance programs led to reduction in these services.21 While attempts to repeal and replace the ACA stalled out in summer 2017, there have been several changes to implementation of the ACA that affect coverage options and people’s likelihood of signing up for or retaining ACA coverage.

In October 2017, the Trump Administration announced it would no longer make payments to insurers for cost-sharing reductions (CSRs). Regardless of whether the federal government reimburses insurers for CSR subsidies, insurers are still legally required under the ACA to offer reduced cost-sharing via silver-level plans to eligible consumers. Many built the loss of CSR payments into their premiums for silver plans for 2018 and again in 2019.22,23 Because premium tax credits on the exchanges are tied to the cost of silver premiums, the effect of the loss of CSR payments was cushioned for many enrollees purchasing insurance through the ACA marketplace.

The individual mandate is no longer in effect as of 2019. As part of tax reform legislation passed in December 2017, Congress reduced the individual mandate penalty to $0 effective in 2019. Repeal of the individual mandate is expected to deter healthier people from enrolling in coverage and thus lead to a sicker—and more expensive—risk pool in the marketplace. Analysis of insurer rate filings shows that plans increased marketplace premiums to account for the loss of the individual mandate.24 Because customers receiving marketplace subsidies will continue to pay sliding-scale premiums based largely on their incomes, these premium increases primarily affect unsubsidized customers and those purchasing individual coverage outside the ACA marketplace. In December 2018, a federal judge in Texas ruled that the change to the law’s individual mandate made the entire law itself unconstitutional, though that decision has no effect as the case works its way through the appeals process.

New, more loosely-regulated plans may now compete with ACA marketplace plans. In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules that will allow more loosely regulated plans – both short-term limited duration (STLD) plans and association health plans (AHPs) – to proliferate on the individual market in competition with ACA-compliant coverage.25 These more loosely regulated plans will serve as a more affordable option for some people who are not eligible for the ACA’s premium tax credits. However, particularly in the case of short-term plans, this lower-cost coverage is generally unavailable to people with pre-existing conditions, and the plans often exclude coverage for certain services.26 These plans will attract disproportionately healthy individuals away from ACA-compliant coverage, thus having an upward effect on premiums in the ACA-compliant individual market.

In 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued new guidance regarding Medicaid waivers and invited states to develop waivers, including some that restrict Medicaid eligibility and enrollment.27 Under the previous administration, CMS approved certain eligibility- and enrollment-related waiver provisions as part of ACA Medicaid expansion waivers. Under the Trump administration, states are seeking to apply these previously approved provisions as well as new restrictions to both expansion and traditional Medicaid populations. The Trump administration also has approved eligibility and enrollment restrictions that have never been approved before, such as conditioning eligibility on meeting work requirements; coverage lock-outs for failure to report changes affecting eligibility; and eliminating retroactive coverage for nearly all Medicaid enrollees, among others. In some states, these provisions apply to both expansion adults and traditional Medicaid populations.

New public charge rules could have a chilling effect on coverage among immigrants. In October 2018, the Trump Administration published a proposed rule that would make changes to “public charge” policies. Under longstanding policy, the federal government can deny an individual entry into the U.S. or adjustment to legal permanent resident (LPR) status (i.e., a green card) if he or she is determined likely to become a public charge. Under the proposed rule, officials would newly consider use of certain previously excluded programs, including Medicaid, in public charge determinations. The changes would likely lead to decreases in participation in Medicaid among legal immigrant families and their U.S.-born children beyond those directly affected by the changes.28

The effect of these policy changes on enrollment and coverage is currently playing out and will continue to develop. After growing for the first few years of ACA implementation, marketplace enrollment declined slightly in 2017 and 2018 then dropped substantially in 2019.29 In the one state that has implemented Medicaid work requirements to date, Arkansas, over 18,000 people lost Medicaid in 2018 for failing to meet work or reporting requirements;30 it is unclear whether these people gained other sources of coverage, but low offer rates of employer coverage among low-wage workers make it likely that many did not.31 In addition, recent research suggests that changes in immigration policy focused on restricting immigration and enhancing immigration enforcement are causing some immigrant families to turn away from public programs, including Medicaid and CHIP.32 As additional data on health coverage becomes available, it will be important to assess the effect of these changes, combined with other economic trends, on health coverage.