The U.S. Government and Global LGBT Health: Opportunities and Challenges in the Current Era

U.S. Government Efforts to Address Global LGBT Health to Date

Most U.S. government efforts to address the health and human rights of LGBT individuals have been broadly cast as part of the U.S. government’s human rights policy and approach1,2,3 rather than through its global health strategies and programs, although they have included health elements. A few have been health-specific, primarily in the context of HIV, particularly related to addressing the impact of the epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender individuals. An overview of these developments and activities follows.

Broader Human Rights & Foreign Policy Efforts

Early on during President Obama’s first term, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton signaled the Administration’s intent to include LGBT issues as part of its human rights agenda, working to address violence and discrimination against people based on sexual orientation or gender identity.4,5 Advancing LGBT human rights has since been identified as a State Department foreign policy priority.6 This has included U.S. engagement at the UN, such as a June 2011 effort at the UN Human Rights Council, led by the U.S. and several other governments, that resulted in the passage of the first-ever UN resolution on sexual orientation and gender identity.7,8 Shortly thereafter, in his annual speech to the UN General Assembly, President Obama spoke of the need to include LGBT individuals in global efforts to protect rights.9

Perhaps most notably, in December of 2011, the White House issued a Presidential Memorandum on International Initiatives to Advance the Human Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Persons, calling for “all agencies engaged abroad to ensure that U.S. diplomacy and foreign assistance promote and protect the human rights of LGBT persons.”10,11 These themes were reinforced that same day in a speech by Secretary Clinton in Geneva.12 The Presidential Memorandum directs agencies to:

- Combat the criminalization of LGBT status or conduct abroad;

- Protect vulnerable LGBT refugees and asylum seekers;

- Leverage foreign assistance to protect human rights and advance non-discrimination;

- Ensure swift and meaningful U.S. responses to human rights abuses of LGBT persons abroad; and

- Engage international organizations in the fight against LGBT discrimination.

Among the main agencies and programs carrying out efforts to address LGBT human rights broadly are:

DRL

The State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) leads U.S. efforts to protect human rights globally, working to protect populations at risk, including LGBT individuals. DRL is responsible for preparing the State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, as required by Congress. Discussion of LGBT human rights issues in these reports has been significantly expanded by the Obama Administration, and they now include a specific section on LGBT rights by country. In addition to these ongoing activities, and timed with the President’s Memorandum, the Administration announced the creation of the Global Equality Fund (GEF), a public-private partnership,13 to be managed by DRL. The GEF is intended to advance LGBT human rights by providing emergency and long term assistance to civil society organizations around the world.14 To date, the GEF has allocated over $7.5 million to more than 50 countries.15

PRM

The State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) works to address the needs of refugees, migrants, and victims of conflict, including those who are LGBT, through its efforts with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as well as through the provision of assistance to individuals.16 In addition, PRM has worked with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to expedite refugee processing for LGBT individuals and developed guidance for adjudicating LGBT refugee and asylum claims.17

USAID

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the main development assistance arm of the U.S. government, has moved to include LGBT issues within its broader development agenda. Specifically, the Agency has created an LGBT Senior Coordinator position to coordinate implementation of the 2011 Presidential Memorandum. It has also included reference to the importance of addressing the rights of LGBT individuals in many of its main policy and guidance documents, including its Policy Framework for 2011-2015,18 Strategy on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance,19 Youth in Development Policy,20 and Country Development Cooperative Strategy (CDCS) Guidance,21 and Global Health Strategic Framework for FY 2012-2016.22 USAID has also added language to its award provisions encouraging, but not requiring, all implementing partners to add non-discrimination provisions that include sexual orientation and gender identity.23 Beyond incorporating LGBT rights into its broader development frameworks, USAID recently released a draft document, the USAID Vision for Action: Promoting and Supporting the Inclusion of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, And Transgender Individuals,24to more directly articulate its work in this area, and includes reference to health barriers as a key challenge facing LGBT people worldwide. Other efforts include the launch of the LGBT Global Development Partnership in April 2013, a public-private partnership25 designed to strengthen capacity of LGBT organizations, provide training, and conduct research on the economic impact of discrimination on LGBT individuals, with health access included as one of the areas to be assessed and monitored. The agency has also begun undertaking an internal effort to raise awareness of LGBT human rights at the agency and field levels, including through the provision of sensitivity training and technical assistance at country missions and by instructing embassies and missions to meet with the LGBT community in their host countries.26,27 Where USAID has undertaken health-specific efforts focused on LGBT individuals and civil society, they have been part of its HIV response under PEPFAR (see discussion below).

MCC

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) is an independent U.S. agency that provides development assistance in order to promote economic growth and reduce poverty through country-compacts in eligible low- and middle-income countries. As part of its assessment of country eligibility for compacts, MCC selection criteria include measures related to civil liberties and human rights.28 In recent years, the MCC has moved to include LGBT rights in its broader assessment of human rights protections when considering country eligibility for assistance as well as continuation of assistance during a compact. For example, the MCC suspended a compact to Malawi due to a “a pattern of actions inconsistent with good policy performance in the areas measured by the Political Rights, Civil Liberties, and Rule of Law indicators,” actions that included “legal changes affecting media freedom, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender human rights, and citizens’ access to justice” (the compact has since been reinstated).29

Global Health-Specific Efforts

While efforts to address LGBT rights within the broader foreign policy and development work of the U.S. government have included health in some cases, they have generally not been health-specific or an explicit part of the U.S. global health agenda. Rather, health-specific activities that address LGBT individuals have primarily been undertaken as part of the U.S. global HIV response, through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Beyond HIV, U.S. government engagement on global LGBT health issues has largely been carried out through diplomatic engagement at the World Health Organization (WHO) and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

PEPFAR

PEPFAR is the largest component of the U.S. global health portfolio, overseen by the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator at the State Department and implemented by several U.S. agencies including USAID, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Department of Defense (DoD). While PEPFAR has included efforts to address the impact of HIV among MSM since it was launched,30 it has only more recently begun to increase its programmatic focus on LGBT individuals, primarily MSM and, to a lesser extent, transgender individuals, in its bilateral HIV work. In May 2011, PEPFAR released its first programmatic guidance on addressing the HIV prevention needs of MSM.31 The guidance is intended to address “the urgent need to strengthen and expand HIV prevention for MSM and their partners and to improve MSM’s ability to access HIV care and treatment”32 and to inform the development of Country Operational Plans (COPs), which document annual U.S. government investments and anticipated results in HIV by country. PEPFAR’s 2014 Gender Strategy discusses how gender norms concerning sexual behavior, sexual orientation, and gender identity can place individuals at increased risk for HIV and/or present barriers to care, and includes LGBT individuals as vulnerable populations to be considered in PEPFAR’s gender programming. More generally, PEPFAR’s Blueprint, its roadmap for achieving an AIDS-Free Generation released in November 2012, includes the importance of improving access to and uptake of HIV services by key populations, including MSM and transgender individuals.”33

Three, smaller-scale PEPFAR initiatives are focused on creating more civil society capacity to help scale up access to PEPFAR’s HIV programs among key populations, including LGBT individuals:

- The “Key Populations Challenge Fund”, a $20 million fund launched in June 2012 to support the expansion of interventions and services for key populations, including MSM, at the country level, focusing in 6 countries and two regions;34,35

- The “Robert Carr Civil Society Network Fund,” also launched in June 201236 by the U.S. along with the United Kingdom, Norway, and the Gates Foundation37 to support civil society organizations in scaling up access for key populations including LBGT individuals. The U.S. is providing $2 million to this effort; and

- The “Local Capacity Initiative Fund,” which provides funding to PEPFAR country and regional teams to support local civil society organizations that advocate for key populations to work to reduce legal and policy structural barriers and stigma and discrimination.38

USAID, PEFPAR’s largest implementing agency, has been addressing the impact of HIV among MSM since it first began carrying out international HIV activities in the 1980s.39 USAID efforts, funded under PEPFAR, to address the health of key populations have included its AIDSTAR2 and Health Policy Projects, both of which have supported MSM civil society capacity building, as well as its Research to Prevention (R2P) project, which included research to document and measure stigma and discrimination. Most recently, in December 2013, to support PEPFAR’s Blueprint, USAID put out a Request for Application (RFA) for a new five year, $72 million cooperative agreement to address key populations.40 This RFA, Linkages Across the Continuum of HIV Services for Key Populations Affected by HIV, marks the first PEPFAR central procurement dedicated to addressing the needs of key populations. It is intended to strengthen the capacity of governments and civil society in PEPFAR partner countries to “implement high quality, sustainable, evidence-based and comprehensive HIV and AIDS prevention, care and treatment services with key populations at scale,” including gay men and other MSM and transgender individuals.

In addition, over the next year, PEPFAR is planning on rolling out workshops for PEPFAR country staff focused on: U.S. policies regarding sexual orientation and gender identity; workplace expectations regarding diversity; facilitating engagement with civil society and community organizations working with LGBT populations; and implementation of emergency response guidelines and protocols during hostile situations that directly involve LGBT populations.41

In addition to PEPFAR’s bilateral HIV programming, the U.S. is the largest donor to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) which itself first approved a strategy to address sexual orientation and gender identity several years prior (in 2009),42 and recently strengthened its focus on promoting human rights for key populations by integrating human rights concerns into its grant-making process43 and launching a pilot initiative to help increase the participation of and “create “safe spaces” for key affected populations, especially those who are criminalized and marginalized.44

WHO and PAHO

Beyond its HIV-focused programming, U.S. government engagement on global LGBT health issues more broadly has taken place in the international, diplomatic arena. Specifically, the U.S. has led efforts to raise LGBT health at the WHO, the directing and coordinating authority for health within the United Nations system.45 In May 2012, the U.S. convened a panel discussion on LGBT health at the sidelines of the World Health Assembly, the annual meeting of the WHO attended by all WHO Member States. The U.S., with a handful of other countries, subsequently petitioned to have the topic of LGBT health included on the agenda of the WHO Executive Board (which determines the broader WHA agenda). The WHO staff prepared a summary report on LGBT health46 to be considered at the May 2013 Executive Board meeting, but several countries petitioned to remove the agenda item for future consideration; it was again not adopted at a January 2014 Executive Board meeting and, while the WHO Director-General has been personally involved in trying to get it back on the agenda, it is unclear when it will be reconsidered. Importantly, this is the first time in the history of WHO that an agenda item has been removed, a fact that reflects the incredible political sensitivity of this issue at the health body.

Despite the continued uncertainty about the inclusion of LGBT health on the WHO agenda, in October 2013, PAHO, the regional body of the WHO representing the Americas, unanimously passed a resolution that had been presented by the U.S. addressing LGBT health including discrimination in the health sector, marking the first time any UN body had adopted a resolution specifically addressing these issues.47,48,49

U.S. Global Health Assistance & the Presence of Anti-LGBT Laws by Country

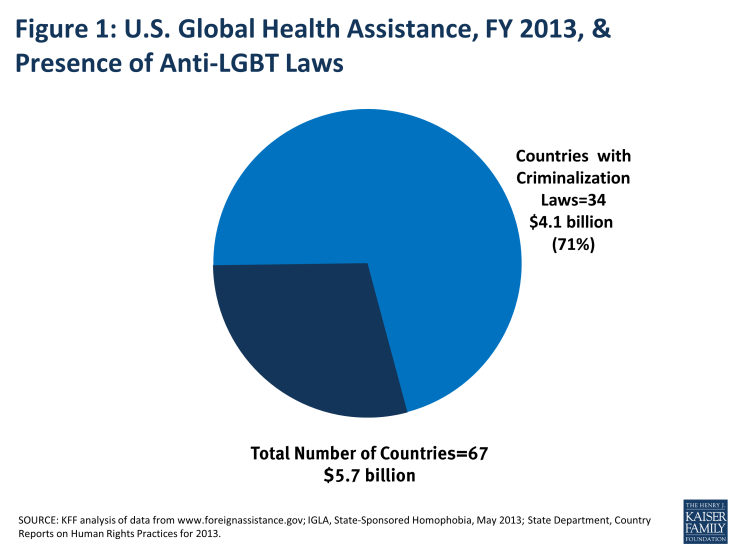

As a backdrop for understanding the legal climate regarding LGBT individuals in countries in which the U.S. government provides global health assistance, the Kaiser Family Foundation analyzed U.S. funding data for FY 2013 and information on criminalization laws by country. This analysis finds that in FY 2013, of the 67 countries that received U.S. global health assistance (totaling $5.7 billion):

- Thirty-four criminalize same-sex behavior, including 3 which impose the death penalty.

- These 34 countries accounted for 71% of U.S. global health assistance ($4.1 billion); eight are among the top 10 recipients of U.S. global health assistance.50

- Most (23) are in Africa; 9 are in Asia and one, each, is in the Oceanic and Latin American/Caribbean regions, respectively. None are in the European/Eurasia region.

- They range in in the number of U.S.-supported global health programs (of 7 major program areas).51 Eleven receive funding from just a single program area while 8 receive funding from all 7 programs; nineteen countries receive funding from 4 or more program areas.

- Twenty-six receive PEPFAR (HIV bilateral) funding, accounting for 71% of PEPFAR funding.

- Countries receiving U.S. global health assistance include India, Nigeria and Uganda, which have recently moved to further criminalize same sex behavior, and several others where such steps are being considered.

Also see Figure 1. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of these data and sources (additional information is provided in an appendix).

| Table 2: U.S. Global Health Assistance, FY 2013, & Presence of Anti-LGBT Laws by Country | ||||

| CountryCriminalizes Homosexuality | Country | TotalU.S. Global HealthAssistance | Number of U.S. Global Health Programs | Region |

| Yes | Afghanistan | 169,937,000 | 6 | Asia |

| Yes | Angola | 49,557,000 | 4 | Africa |

| Armenia | 2,868,000 | 4 | Europe/Eurasia | |

| Yes | Bangladesh | 96,883,000 | 6 | Asia |

| Benin | 23,466,000 | 3 | Africa | |

| Yes | Botswana | 61,294,000 | 1 | Africa |

| Brazil | 1,081,000 | 1 | LAC | |

| Burkina Faso | 11,571,000 | 2 | Africa | |

| Yes | Burma | 20,848,000 | 4 | Asia |

| Yes | Burundi | 40,100,000 | 5 | Africa |

| Cambodia | 37,914,000 | 7 | Asia | |

| Yes | Cameroon | 25,325,000 | 1 | Africa |

| Chad | 500,000 | 2 | Africa | |

| China | 2,977,000 | 1 | Asia | |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 135,269,000 | 1 | Africa | |

| DRC | 166,018,000 | 7 | Africa | |

| Djibouti | 1,800,000 | 1 | Africa | |

| Dominican Republic | 13,824,000 | 2 | LAC | |

| Yes | Egypt | 2,893,000 | 1 | Africa |

| Yes | Ethiopia | 329,754,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Georgia | 3,664,000 | 3 | Europe/Eurasia | |

| Yes | Ghana | 73,014,000 | 6 | Africa |

| Guatemala | 26,846,000 | 3 | LAC | |

| Yes | Guinea | 17,880,000 | 3 | Africa |

| Yes | Guyana | 8,866,000 | 1 | LAC |

| Haiti | 162,882,000 | 4 | LAC | |

| Honduras | 3,578,000 | 2 | LAC | |

| Yes | India | 77,560,000 | 4 | Asia |

| Indonesia | 48,924,000 | 4 | Asia | |

| Jordan | 49,000,000 | 3 | Asia | |

| Kazakhstan | 2,234,000 | 1 | Asia | |

| Yes | Kenya | 356,030,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 4,282,000 | 1 | Asia | |

| Yes | Lebanon | 11,993,000 | 1 | Asia |

| Lesotho | 26,165,000 | 1 | Africa | |

| Yes | Liberia | 53,932,000 | 6 | Africa |

| Madagascar | 52,930,000 | 5 | Africa | |

| Yes | Malawi | 138,657,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Yes | Maldives | 955,000 | 1 | Asia |

| Mali | 64,241,000 | 6 | Africa | |

| Yes | Mozambique | 273,804,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Yes | Namibia | 77,877,000 | 1 | Africa |

| Nepal | 40,489,000 | 5 | Asia | |

| Niger | 4,200,000 | 3 | Africa | |

| Yes* | Nigeria | 625,974,000 | 6 | Africa |

| Yes | Pakistan | 31,349,000 | 3 | Asia |

| Yes | Papua New Guinea | 4,853,000 | 1 | Oceania |

| Philippines | 36,632,000 | 4 | Asia | |

| Rwanda | 136,694,000 | 6 | Africa | |

| Yes | Senegal | 64,416,000 | 6 | Africa |

| Yes | Sierra Leone | 5,500,000 | 3 | Africa |

| Yes* | Somalia | 1,911,000 | 1 | Africa |

| South Africa | 489,576,000 | 3 | Africa | |

| Yes | South Sudan | 64,371,000 | 6 | Africa |

| Yes | Swaziland | 26,054,000 | 1 | Africa |

| Tajikistan | 7,500,000 | 4 | Asia | |

| Yes | Tanzania | 443,442,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Thailand | 1,000,000 | 1 | Asia | |

| Timor-Leste | 2,013,000 | 2 | Asia | |

| Yes | Uganda | 409,244,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Ukraine | 29,587,000 | 3 | Europe/Eurasia | |

| Yes | Uzbekistan | 3,045,000 | 1 | Asia |

| Vietnam | 65,676,000 | 1 | Asia | |

| West Bank & Gaza | 1,929,000 | 1 | Asia | |

| Yes* | Yemen | 11,689,000 | 3 | Asia |

| Yes | Zambia | 363,207,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Yes | Zimbabwe | 123,263,000 | 7 | Africa |

| Total (all countries) | 67 countries | $5,722,807,000 | — | — |

| Subtotal (w/laws) | 34 countries | $4,065,477,000 | — | — |

|

NOTES: *Imposes the death penalty (in Nigeria, this applies to 12 northern states). Represents FY 2013 enacted amounts. Does not include additional funding that may be provided to individual countries through regional programs or funding for “other” global health of $10,489,000 that was provided to Afghanistan in 2013.LAC = Latin America & the Caribbean.

SOURCES: KFF analysis of data from www.foreignassistance.gov; IGLA, State-Sponsored Homophobia, May 2013; State Department, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2013. |

||||

U.S. RESPONSE TO RECENT ACTIONS IN NIGERIA, UGANDA, AND ELSEWHERE

The U.S. has had varying responses to the recent actions to further criminalize homosexuality and/or restrict LGBT rights taken by the governments of Russia, India, Nigeria and Uganda. These responses have ranged from statements of concern by Administration officials and Members of Congress, to diplomatic meetings, requests for assurances about protections of individuals seeking health services and, in the case of Uganda, the review and even suspension of some U.S. health and other development assistance. The range in responses reflects several factors including U.S. bilateral relations more broadly with each of these countries, the unique context of each country, the nature of the recent change in the law and any related enforcement, and the extent to which the country receives health and other development assistance from the United States. Russia, for example, receives no development assistance from the U.S. government and the USAID mission has been closed, and current U.S.-Russia bilateral relations are primarily focused on addressing the crisis in Ukraine. India receives health (and some other development) assistance from the U.S., although this has diminished over time as the country has moved into middle income status; in addition, as described below, the recent change to Indian law was made by the Indian Supreme Court and is still being challenged by several parties including the central Indian government. Nigeria and Uganda, on the other hand, have been seen as important partners in responding to HIV and other health challenges. Both are among the top 10 recipients of health assistance from the U.S. government and were among the original 15 PEPFAR focus countries, and still are top PEPFAR recipients.52 They are also focus countries under the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) and priority countries for USAID’s family planning, maternal and child health, and TB programs. In addition, while each has long had laws criminalizing same sex behavior, they had, until recently, rarely been enforced.

An overview of U.S. responses to recent developments in these four countries is provided below.

Russia

While Russia decriminalized same sex behavior in 1993,53 President Putin, in June 2013, signed into law an amendment to an existing federal law On Protecting Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development, extending it to include the propaganda of “nontraditional sexual relations to minors”.54 The law includes administrative fines for individuals, organizations, and foreigners for such propaganda, and further subjects foreigners to prison and deportation from Russia. The law was met by international criticism,55 including by the U.S. government, in part because it was passed just months before the Winter Olympics was to be held in Sochi, Russia and most of the international response centered on concerns about Sochi. The U.S. government issued a travel warning for LGBT travelers, which remains in effect today.56 More than 80 Members of Congress sent a letter to Secretary Kerry expressing their concern about the implications of the law for the safety and well-being of LGBT and LGBT-supporting individuals involved in or attending the Olympics and requesting information about diplomatic and other actions the State Department intended to take.57 President Obama and other administration officials have criticized the law58,59 and the State Department’s Human Rights Country Report on Russia describes the law as limiting the rights of free expression and assembly for citizens who wish to publicly advocate for LGBT rights or express the opinion that homosexuality is normal including materials that “directly or indirectly approve of people who are in nontraditional sexual relationships.”60

India

In December 2013, a two-person bench of the Indian Supreme Court reinstated a colonial-era law (Section 377 of the Penal Code) that described homosexual acts as ��against the order of nature” and punishable by up to life in prison. The ruling overturned a 2009 ruling by the Delhi High Court, which had found the law unconstitutional, with the Supreme Court stating that only Parliament could make such changes.61 Many have spoken out62,63 against this ruling including the Indian government, which filed a petition challenging the ruling that has since been rejected.64,65 Other avenues for addressing the ruling are being pursued, including requesting a curative petition (for the Court to hear the case even after a petition has been dismissed) and legislative action.66 The State Department has expressed its “deep concern” about the ruling.67 The ruling is noted in the State Department’s Human Rights Country Report on India and in its travel advisory.68

Nigeria

Nigeria has long criminalized same sex behavior (including penalty of death in some northern states of the country) but a recent bill signed into law by President Jonathan further criminalizes LGBT people and groups. The law mandates a 14-year prison sentence for anyone entering a same-sex union and a 10-year term for “a person or group of persons who supports the registration, operation and sustenance of gay clubs, societies, organizations, processions or meetings”. The law also states that “a person or group of persons who … supports the registration, operation and sustenance of gay clubs, societies, organizations, processions or meetings in Nigeria commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of 10 years imprisonment.”69,70 Incidents of violence and criminalization following the passage of the law have been documented.71,72 Many in the international community have spoken out about this law including the UN Secretary General;73 the UN Human Rights Council;74 UNAIDS75 and the Global Fund, which issued a joint statement of concern;76 President Obama, Secretary Kerry, and the U.S. Ambassador to Nigeria. Secretary Kerry has said, for example, that “Beyond even prohibiting same sex marriage, this law dangerously restricts freedom of assembly, association, and expression for all Nigerians.”77 The State Department’s Human Rights Country Report on Nigeria critiques the law78 and the State Department’s travel advisory for Nigeria warns LGBT travelers about its potential implications.79 While some have called for a review of the U.S. government’s development assistance portfolio in Nigeria, particularly through PEPFAR, such a review has not yet been announced.

Uganda

Like Nigeria, Uganda has also long had a law criminalizing homosexuality. However, in February 2014, Uganda’s President Museveni signed a bill, originally proposed in 2009 (the original version included the death penalty), that imposes further criminal sanctions on LGBT individuals and those who support them.80 Since the signing of the bill, increased incidents of targeting and criminalization have been reported.81,82,83The signing of the bill was largely unexpected, particularly due to earlier successful attempts to prevent passage and some indications by President Museveni that he would not sign it. The response by the U.S. and others to Uganda has been the most pronounced. Several donors, including the United Kingdom, Norway, Denmark,84 and the World Bank85 have stated that they are examining, redirecting, and/or suspending aid to the country, or indicated that their aid does not go to directly to the Ugandan government. UNAIDS86,87 and the Global Fund88 have expressed their strong concern. President Obama,89 Secretary Kerry,90 other Administration officials, and Members of Congress91 have issued strong statements and the Administration announced it would undertake a review of its portfolio (health and non-health) in Uganda. The USAID Mission Director in Uganda issued a memo to inform implementing partners that all external events, ribbon cuttings, workshops, launches, and/or program close-outs would require prior-approval.92 Recently, the Administration announced several additional steps it was taking to respond to the situation, including: shifting some funding away from the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda (IRCU), an organization that receives PEPFAR support but one that has also spoken out in favor of the law ($2.3 million in treatment funding will continue to be provided to the IRCU but $6.4 million will be redirected to other organizations); suspension of a CDC study of MSM due to concern about staff and survey respondents’ safety; redirection of U.S. funding to Uganda for tourism; and relocation of several Department of Defense events that were scheduled to take place in Uganda.93 The State Department’s travel advisory to LGBT travelers states that the “Embassy advises all U.S. citizens who are resident and those visiting Uganda to carefully consider their plans in light of this new law” 94 (the State Department’s Human Rights Country Report was published before the passage of the new law).

Despite these actions, and assurances by the Ugandan government that health services for LGBT individuals would not be affected, on April 3, a U.S.-funded health clinic and medical research facility, the Makerere University Walter Reed Project (MUWRP), was raided by Ugandan authorities and an employee arrested for conducting “unethical research” and “recruiting homosexuals.” In its response, the State Department wrote, “[w]hile that individual was subsequently released, this incident significantly heightens our concerns about respect for civil society and the rule of law in Uganda, and for the safety of LGBT individuals” and has temporarily suspended the MUWRP operations to ensure the “safety of staff and beneficiaries, and the integrity of the program”.95 A recent statement by the new U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, Ambassador Deborah Birx, underscored PEPFAR’s intention to continue serving those in need in countries in which they faced violence or other legal action due to their sexual orientation, gender identity or other factors, recognizing the PEPFAR has long operated in such environments and will “not back down” now.96