The Federal Courts' Role in Implementing the Affordable Care Act

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) increases access to affordable health insurance and reduces the number of uninsured by expanding eligibility for Medicaid and providing for the establishment of Marketplaces that offer qualified health plans and administer premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions to make coverage affordable. The ACA also contains private insurance market regulations, such as the guaranteed issue provision, which prevents health insurers from denying coverage to people for any reason, including pre-existing conditions, and the community rating provision, which allows health plans to vary premiums based only on age, geographic area, tobacco use, and number of family members, thereby prohibiting plans from charging higher premiums based on health status or gender. The ACA’s minimum essential coverage provision, known as the individual mandate, requires most people to maintain a certain level of health insurance for themselves and their tax dependents in each month beginning in 2014, or pay a tax. The Congressional authors of the ACA believed that without the individual mandate, the Marketplaces and private insurance market reforms would not work effectively due to the effects of adverse selection when healthy people otherwise would choose to forego insurance.

Since the ACA’s enactment, a number of lawsuits have been filed challenging various provisions of the law. In National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the individual mandate but effectively made the Medicaid expansion a state option. In Hobby Lobby v. Burwell, the Supreme Court ruled that closely held for-profit corporations may exclude contraceptives from their health plan packages if their owners have religious objections. The Court’s decision effectively results in a contraceptive coverage gap for women who work for a closely held corporation whose owners have religious objections to contraceptives. A series of lawsuits filed by non-profit religiously affiliated employers challenging the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement remains pending in the lower federal courts, and HHS has issued interim final rules for religiously affiliated nonprofits. HHS also issued proposed rules regarding closely held corporations with religious objections to contraceptive coverage. HHS is seeking comments on how to extend the same accommodation provided to eligible nonprofits to closely held corporations with religious objections to contraceptives. In addition, some cases challenging the availability of premium subsidies in the Federally-Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) are progressing through the federal courts. All of this litigation has altered, or has the potential to alter, the way in which the ACA is implemented and consequently could affect the achievement of the law’s policy goals, such as the number of people who obtain affordable health insurance, and what is required to be included in a health plan. This issue brief examines the federal courts’ role to date in interpreting and affecting implementation of the ACA, with a focus on the provisions that seek to expand access to affordable coverage.

Background

The ACA’s Medicaid Expansion

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage to people with low incomes and is jointly funded by the federal and state governments. States that choose to participate in the Medicaid program are required to cover certain groups of people. The mandatory coverage groups have been expanded by Congress several times since the program’s enactment in 1965, and prior to the ACA generally included pregnant women and children under age six with family incomes at or below 133% of the federal poverty level (FPL), children ages six through 18 with family incomes at or below 100% FPL, parents and caretaker relatives who meet the financial requirements for the former AFDC cash assistance program, and people who qualify for Supplemental Security Income benefits based on low income and disability status. The ACA again expanded the mandatory coverage groups to include nearly all non-pregnant adults under age 65 with incomes up to 138% FPL ($16,104 per year for an individual in 2014), as of 2014. (The ACA expands Medicaid eligibility to 133%FPL and includes an income disregard of five FPL percentage points, effectively making the income limit 138% FPL.) To fund the expansion, the ACA provides that the federal government will cover 100% of the states’ costs of covering newly eligible adults beginning in 2014, gradually decreasing to 90% in 2020 and thereafter. While states can implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion at any time, the statute ties full federal funding to specific years (2014, 2015, and 2016). Nationally, 17 million uninsured non-elderly adults may meet the income and citizenship criteria to be eligible for Medicaid under the ACA’s expansion.

Premium Subsidies and Related Marketplace Coverage Provisions

The ACA expands access to affordable insurance coverage by providing for qualified health plans to be purchased through Marketplaces. The law gives states the option to establish their own Marketplaces. If states do not elect to do so, the ACA provides for the FFM as a default so that Marketplaces are available in each state. States also have the option to operate a Marketplace in partnership with the federal government by assuming control over health plan management and/or consumer assistance functions.

The ACA’s premium subsidies are the central mechanism through which the law guarantees affordable coverage to individuals who purchase insurance on the Marketplace. The subsidies include advance payment of tax credits for people with incomes between 100-400% FPL ($11,670-$46,680 for an individual in 2014) and cost-sharing reductions for people with incomes from 100-250% FPL ($11,670-$29,175 per year for an individual in 2014). In its implementing regulations, the IRS has interpreted the ACA to allow premium subsidies for individuals who purchase coverage through both State-Based Marketplaces and the FFM. The IRS rule provides that the premium subsidies shall be available to anyone enrolled in a qualified health plan through a Marketplace and then adopts by cross-reference an HHS definition of “Marketplace” (formerly called “Exchange”) that includes any Marketplace, regardless of whether the Marketplace is established and operated by a State or by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

While the ACA’s individual mandate requires most Americans to have insurance or pay a tax, certain people are exempt from the tax, including those whose annual insurance premiums would exceed eight percent of their household adjusted gross income. The ACA’s premium subsidies lower the cost of insurance for individuals – and thereby subject more people to the tax for failing to satisfy the individual mandate if they do not purchase the affordable coverage available through the Marketplace.

The ACA also requires larger employers to offer insurance, known as the employer mandate, or pay a tax, known as the employer shared responsibility payment. The applicability of the employer mandate is also dependent on the premium subsidies because the Employer Shared Responsibility Payment is triggered when one of an employer’s full time workers receives a Marketplace premium subsidy. If there are no subsidies, then an employer would never be subject to the Employer Shared Responsibility Payment for failure to comply with the employer mandate.

Key Questions

1. What Effect Has the Supreme Court’s Decision Had on Implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion?

Implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion is effectively a state option due to the Supreme Court’s ruling on its constitutionality. Prior to NFIB, the Court had long recognized that Congress could attach conditions to states’ receipt of federal funds under its Spending Clause power. This enabled Congress to achieve certain policy goals that it could not attain by legislating directly through its enumerated powers, allowing Congress to reach issues of public health, safety, and welfare that otherwise were reserved to the state’s police power. In NFIB, the Court for the first time held that the Medicaid expansion is unconstitutionally coercive of states because states did not have adequate notice to voluntarily consent, and the HHS Secretary could withhold all existing federal Medicaid funds for state non-compliance. The Court remedied the constitutional violation by circumscribing the Secretary’s enforcement authority. The ACA’s Medicaid expansion remains in the statute as a mandatory coverage group. However, the practical effect of the Court’s decision is that the Secretary may withhold only ACA Medicaid expansion funds, and not all or part of a state’s federal funds for the rest of its Medicaid program, if a state does not comply with the Medicaid expansion.

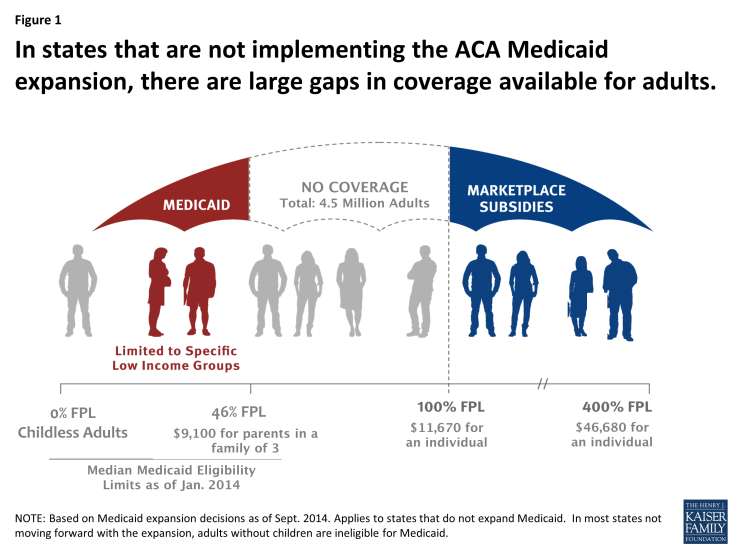

The Court’s decision has resulted in a coverage gap for over 4.5 million people with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to qualify for Marketplace subsidies in states that have not implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to date (Figure 1). (The coverage gap is reduced from 4.8 million to 4.5 million with Pennsylvania’s implementation of the expansion.) Twenty-eight states (including DC) are implementing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, and some other states continue to consider implementation. In states that expand Medicaid, the historical gaps in eligibility for adults with low-incomes are eliminated, and millions of previously uninsured people have new access to affordable health coverage. However, in states that have not expanded Medicaid, people with incomes above the existing financial eligibility levels but below the federal poverty level are left without access to affordable health insurance because they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to qualify for Marketplace premium subsidies. Because the ACA envisioned people with low incomes receiving Medicaid nationally, the law does not provide premium subsidies for most people with incomes below the federal poverty level even if they are ineligible for Medicaid. As a result of the Court’s NFIB decision, Medicaid eligibility for adults in states not moving forward with the ACA’s expansion is limited. As of January 2014, the median eligibility level for parents in states not moving forward is 46% FPL (about $9,000 per year for a family of three), and among these states, only Wisconsin provides full Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children as of 2014.

Figure 1: In states that are not implementing the ACA Medicaid expansion, there are large gaps in coverage available for adults.

2. What are the most recent Federal lawsuits Challenging the ACA’s Premium Subsidies about?

The plaintiffs in the most recent lawsuits are individuals who do not wish to purchase insurance and employers who do not want to pay a tax if their employees qualify for premium subsidies in states that have a Federally Facilitated Marketplace. For example, one plaintiff who lives in West Virginia expects to earn $20,000 in 2014. Without premium subsidies, he would be exempt from the individual mandate because the cost of the Marketplace insurance available to him exceeds 8% of his annual income. With subsidies, Marketplace coverage becomes affordable for him within the meaning of the ACA, and he must purchase insurance at a subsidized cost of $21 per year or pay the federal tax for failing to satisfy the individual mandate. Other plaintiffs include employers headquartered in Missouri, Texas, and Kansas (all states that have not set up their own State-Based Marketplace and therefore have defaulted to the FFM). These employers either do not offer health insurance to their full-time workers or the insurance they offer does not meet the minimum standards set by the ACA. Consequently, if one of their full-time employees receives a premium subsidy for purchasing Marketplace coverage, the Employer Shared Responsibility Payment is triggered. On the other hand, if premium subsidies are not available to individuals enrolled in a plan on the FFM, then these employers would not be subject to the ESRP.

The plaintiffs contend that the IRS does not have the authority to grant premium subsidies for individuals who purchase plans on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace. The controversy lies in the wording of one sentence of the ACA: “the premium [subsidy] amount” is based on the cost of a “qualified health plan. . . enrolled in through [a Marketplace] established by the State under [section] 1311 of the [ACA].” The plaintiffs argue that the FFM is not a Marketplace “established by the State” and therefore the IRS has exceeded the authority delegated to it by Congress to make rules implementing the ACA.

In response, the federal government contends that the IRS acted within its authority in interpreting the ACA. The federal government argues that the IRS rule providing premium subsidies in the FFM is legal because a Marketplace “established by the State” also means one established by HHS standing in the shoes of the State. Section 1321 of the ACA directs the HHS Secretary to establish “such [Marketplace]” if a state does not create its own, and the government contends that “such [Marketplace]” is understood to be “[a Marketplace] established by the State under [Section] 1311.” The government further contends that if the wording is ambiguous, then the provision creating premium subsidies needs to be read in the context of the whole ACA, and when looked at in its entirety, it is clear that Congress intended premium subsidies to be available to people in all states, regardless of whether the state has established its own Marketplace.

3. What Have the Federal Appeals Courts Decided To Date About the Availability of Premium Subsidies in the Federal Marketplace ?

To date, two federal appeals courts have ruled on the legality of the IRS rule authorizing premium subsidies in the FFM. These decisions are summarized in Table 1 below.

Halbig v. Burwell (DC Circuit Court of Appeals)

On July 22, 2014, a three judge panel from the DC Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, holding that the language of the ACA is clear that premium subsidies can only be provided for individuals enrolled in Marketplaces established by a State. The DC Circuit found that the IRS rule contradicts the unambiguous words of the ACA, and therefore the IRS overstepped its authority by allowing premium subsidies in the FFM. The DC Circuit observed that when the language of a statute is clear, both the courts and administrative agencies must defer to the statute’s plain meaning. The DC Circuit also concluded that the other provisions of the ACA can continue to work without the availability of premium subsidies through the FFM. On September 4, 2014, the DC Circuit announced that the entire court will rehear the case.

King v. Burwell (4th Circuit Court of Appeals)

On July 22, 2014, a few hours after the DC Circuit decision, a three judge panel from the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals (which covers Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia) upheld the IRS’s regulation providing for premium subsidies in the FFM. The 4th Circuit observed that the ACA’s provision about the availability of Marketplace premium subsidies cannot be read in isolation from the rest of the statute. The 4th Circuit ruled that the ACA’s language is ambiguous and therefore the IRS has the authority to reasonably interpret the ACA. The 4th Circuit also found that the IRS’s interpretation is based on a permissible construction of the statute and furthers the ACA’s broad policy goals of increasing coverage and making coverage more affordable. The plaintiffs have asked the Supreme Court to review the decision.

| Table 1: Federal Appeals Court Rulings About Federal Marketplace Subsidies as of July 2014 | ||

| Issue |

D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals panel decision

(Halbig v. Burwell)

Rehearing en banc scheduled for Dec. 17, 2014 |

4th Circuit Court of Appeals panel decision

(King v. Burwell)

Cert. petition pending before Supreme Court

|

| Is the ACA’s statutory language about the availability of Marketplace premium subsidies clear? | Yes – the ACA is clear that the Federally Facilitated Marketplace is not a Marketplace established by a state and that premium subsidies are available only through state-established Marketplaces | No – the ACA’s language about the availability of Marketplace premium subsidies is ambiguous; courts should not review a statutory provision in isolation from the rest of the law |

| Is the IRS rule offering premium subsidies in the Federally Facilitated Marketplace a legal exercise of the agency’s discretion, within the bounds of authority delegated by Congress? | No – agency and court must defer to statute’s plain meaning; ACA does not authorize IRS to provide premium subsidies in the Federally Facilitated Marketplace; this interpretation does not render other ACA provisions unworkable or unreasonable | Yes – court must defer to IRS and uphold rule as permissible exercise of agency discretion; IRS can decide whether premium subsidies are available in Federally Facilitated Marketplace; IRS’s decision advances ACA’s broad policy goals of increasing coverage and decreasing insurance costs, and premium subsidies are essential to facilitate ACA’s guaranteed issue and community rating provisions |

4. What is the status of premium subsidies in the Federal Marketplace now?

Currently, premium subsidies remain available for all individuals regardless of whether they enroll in a plan through a Marketplace established by a State or the Federally Facilitated Marketplace established by HHS. Despite the conflicting federal appeals court decisions, the IRS rule authorizing premium subsidies in all Marketplaces remains in effect.

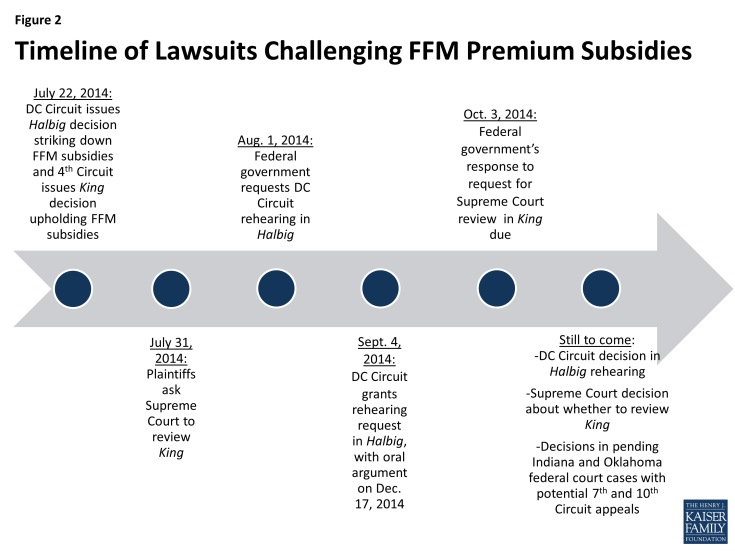

However, the conflicting appeals court decisions to date are unlikely to be the last word on the availability of premium subsidies in the FFM (Figure 2). As mentioned above, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals granted the federal government’s request for a rehearing en banc in Halbig, in which all 11 active judges will review the case. As a result, the Halbig panel decision invalidating the IRS rule could be upheld, overturned, or modified. Meanwhile, the plaintiffs in King have appealed the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals decision upholding the IRS rule directly to the Supreme Court. Only four justices need to vote to accept review of case. The Supreme Court usually waits until there is a split between appeals courts on the same issue before taking review of a case. But the Court may decide that it wants to weigh in on this issue. In addition, similar challenges to the IRS rule about premium subsidies in the FFM are pending decision in federal district courts in Indiana (Indiana v. IRS, No. 1:13-cv-1612 (S.D. Ind.)) and Oklahoma (Pruitt v. Burwell, No. CIV-11-030-RAW (E.D. Okla.)). One or both of those cases eventually could be appealed to the 7th and 10th Circuit Courts of Appeals, respectively, setting up another possible conflict among the federal appellate courts.

5. What are the policy implications of the Courts’ Decisions about the Availability of Premium Subsidies in the Federal Marketplace?

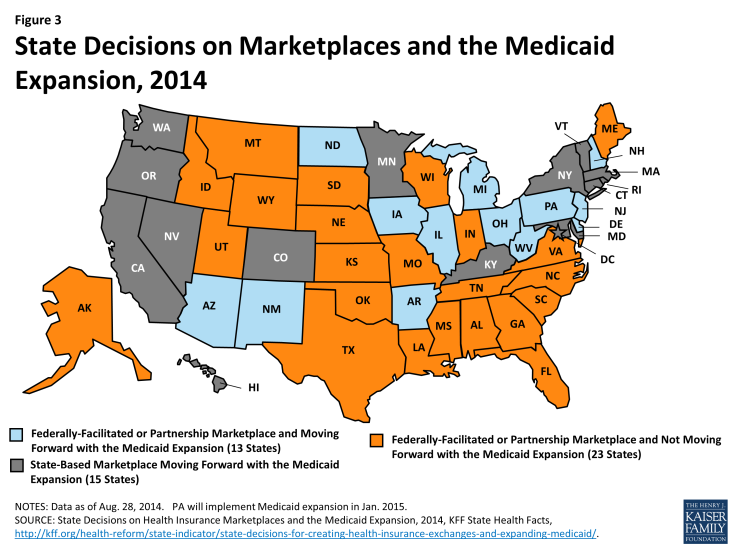

The courts’ decisions about the availability of premium subsidies in the FFM could affect the number of people who ultimately have access to affordable coverage under the ACA. As of 2014, only sixteen states plus the District of Columbia have elected to set up their own Marketplaces; the remaining thirty–four states are presently relying on the FFM (Figure 3). Nearly five million people who purchased coverage in the FFM received premium subsidies in 2014, and it is estimated that over nine million people are eligible for premium subsidies on the FFM.

If the IRS rule authorizing premium subsidies for individuals purchasing coverage on the FFM is ultimately overturned, there could potentially be disruption in the health insurance market in states using the FFM. The ACA’s goal of insuring most Americans would at risk, and millions of people could lose access to premium subsidies, and most likely would become uninsured. Without subsidies, many more people would not be subject to the individual mandate because the cost of coverage would exceed eight percent of their household income. Similarly, without premium subsidies, employers in states with an FFM would not be subject to the ESRP, and some employers may decide to not offer coverage or offer coverage that does not meet the minimum standards of the ACA. If the individual mandate and employer mandate are not generally applicable in the FFM, while the ACA’s guaranteed issue and community rating provisions continue to apply, then most likely, sick people would sign up for insurance at higher rates than healthier people. This could result in a “death spiral” and raise premiums for people in the private insurance market, an outcome that the ACA sought to avoid.

However, if the IRS rule is overturned, there may be solutions to preserve premium subsidies for people seeking affordable coverage under the ACA. For example, many states that now use the FFM would likely create a State-Based Marketplace to ensure access to premium subsidies. It is unclear whether states could establish their own Marketplaces but contract back with the federal government to operate the website to enroll consumers, and thereby allow their residents to qualify for premium subsidies. But like the Medicaid expansion decision, the decision to create a State-Based Marketplace could be subject to political and policy opposition, and some states may decide not to create a State-Based Marketplace, placing many of their residents at risk of becoming uninsured.

Looking Ahead

Court decisions about how to interpret the ACA will continue to affect the number of people who ultimately obtain affordable coverage. At present, access to Medicaid up to 138% FPL is dependent upon where people live because the Supreme Court held that implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion is effectively a state option. Depending upon how the lawsuits challenging the IRS rule providing premium subsidies in the FFM are resolved, access to affordable Marketplace coverage also could be dependent upon where people live. In this scenario, state decisions to not expand Medicaid and also to not create a State-Based Marketplace could have a compounded effect, leaving even more people in a more expansive coverage gap. While premium subsidies currently remain available in all Marketplaces, and a final ruling on this issue is not expected for some time, the courts have the potential to continue to impact the extent to which the ACA achieves its policy goals of increasing access to affordable coverage and reducing the number of uninsured. Over the coming months, it will be important to watch for additional developments as the pending lawsuits progress.