The Coverage Provisions in the Affordable Care Act: An Update

Health Insurance Market Reforms

Consumer Protections

On September 23, 2010, a number of ACA provisions took effect, including the elimination of lifetime limits on coverage, restrictions on annual limits on coverage, prohibition on rescinding coverage except in cases of fraud, and the elimination of pre-existing condition exclusions for children. These early market reforms were intended to provide immediate relief to consumers, especially those with high health care needs, who faced limits on coverage or the potential loss of coverage. Other ACA provisions that took effect six months after enactment included protections allowing consumers the right to choose their own doctors, the right to appeal health plan decisions, and the right to access out-of-network emergency care.1

All individual and group health plans must provide coverage to any applicant, regardless of health status, gender, or any other factors.2 Prior to the ACA, insurers in the individual market were allowed to deny people coverage based on their perceived health risk. As a result, those without access to employer-sponsored insurance who had acute or chronic health conditions, such as cancer or diabetes, were often unable to purchase coverage. Even women, especially those of childbearing age, could be denied coverage because of their expected higher use of health care services. The ACA required guaranteed issue and renewability of coverage and prohibited insurers from imposing pre-existing condition exclusions on coverage. These provisions went into effect on January 1, 2014. Prior to the implementation of the guaranteed issue requirement, the ACA created the temporary Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Plan for those who had been denied coverage and who had been uninsured for at least six months. While this program provide stopgap coverage for some, the coverage was unaffordable for many.

On January 1, 2014, new premium rating rules went into effect for plans in the individual and small group markets.3 These rules prohibit insurers from adjusting premiums based on a person’s health status. Insurers may only adjust premiums based on the following factors:

- Individual versus family enrollment: insurers may vary rates based on the number of family members enrolled in the plan.

- Geography: insurers may charge different rates in different areas across the state.

- Age: insurers may charge older adults more than younger adults; however, the variation in premiums is limited to 3 to 1, meaning insurers can’t charge older adults more than three times what they charge younger adults.

- Tobacco use: insurers may charge tobacco users up to 1.5 times what they charge those who do not use tobacco products.

To ease the transition to the new market reforms, the ACA exempted certain plans from some of the new health insurance requirements. These plans, referred to as grandfathered plans, are plans that were in place as of March 23, 2010 (the day the ACA was enacted) and have undergone minimal changes over time. To maintain grandfathered status, plans must not eliminate benefits to diagnose or treat a condition; increase cost sharing beyond certain specified limits; or reduce the employer share of the premium by more than five percentage points.4 Grandfathered plans are exempt from some of the new insurance market rules, including those relating to essential health benefits, the provision of preventive services with no cost-sharing, and review of premium increases of 10% or more.5 They must, however, extend coverage to dependents up to age 26 and eliminate lifetime and annual limits on coverage. In addition, grandfathered group plans can no longer impose pre-existing condition exclusions on children or adults. According the Kaiser/HRET 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey, 26% of covered workers were enrolled in grandfathered plans in 2014, down from 36% in 2013.6

All group and individual health plans must provide a uniform summary of benefits and coverage (SBC) to applicants and enrollees. The ACA requires insurers and health plans to provide consumers with standardized and easy-to-read information about the plan using a common form that is intended to make it easier for consumers to compare plans. The SBC must describe the main features of the plan, including covered benefits along with any limitations or exclusions, cost sharing requirements, and whether it meets minimum essential coverage and value standards. The SBC must also include examples of how the policy or plan would cover care for certain health conditions or scenarios, showing hypothetical costs for consumers and how much the plan would pay. Currently, the form shows coverage examples for a normal delivery and managing type 2 diabetes. Finally, the SBC includes uniform definitions of common insurance-related terms. A recently released proposed rule would make some changes to the SBC effective for plan years and open enrollment periods beginning after September 1, 2015.7

Coverage of Preventive Services

Private health insurance plans generally must provide coverage for a range of preventive health services without requiring any patient cost-sharing (co-payments, deductibles, or co-insurance). These rules apply to all private plans, including individual, small group, large group, and self-insured plans, though grandfathered plans are exempt from this requirement.8 The list of required preventive services may be divided into three broad categories:

- Evidence-based services rated A or B by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

- Routine Immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which include coverage for both adult and child immunizations such as influenza, meningitis, hepatitis A and B, human papillomavirus (HPV), measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (chicken pox).

- Preventive services for children and youth recommended by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bright Futures Project, including immunizations, behavioral and development assessments, and screening for autism, vision and hearing impairment, tuberculosis, and certain genetic diseases.

Private health insurance plans generally must provide coverage for an additional set of preventive health services for women without cost-sharing requirements. These services include well-woman visits, all FDA-approved contraceptives, broader screening and counseling for sexually-transmitted infections, breastfeeding support and supplies, and domestic violence screening. Certain religious employers (houses of worship) are specifically exempt from the contraceptive coverage requirement and are not required to include coverage for contraceptives in their health plans. An accommodation was established for certain non-profit religious organizations that object to providing these services (such as religiously-affiliated hospitals or universities). Organizations that qualify for the accommodation do not have to arrange or pay for contraceptive coverage, but must instead send a form to HHS or their insurance company stating their objection to covering contraceptives. The insurance company then provides the coverage without cost-sharing.9 In June 2014, the Supreme Court held in the Burwell vs. Hobby Lobby decision that some closely-held for-profit corporations may also exclude contraceptive coverage from their health plans if their owners have sincerely held religious objections to this requirement.10 In response to the Court’s decision, the Obama Administration issued a proposed rule to expand the “accommodation” in place for non-profit organizations with religious objections to birth control services to closely-held for-profit companies.11

Approximately 76 million people (including almost 19 million children) have received no-cost coverage for preventive health services since the ACA preventive services coverage rules took effect.12 This coverage went into effect on September 23, 2010 for new individual and employer-based coverage (grandfathered plans are exempt). Despite the length of time the benefit has been in place, awareness of the coverage remains low.13

The ACA improves access to preventive services in Medicare and Medicaid. The ACA eliminates cost-sharing for certain Medicare covered preventive services (those recommended A or B by the USPSTF), waives the Medicare deductible for colorectal cancer screenings, and provides coverage for personalized prevention plan services, which include an annual health risk assessment. In Medicaid, the ACA provides states that offer coverage for recommended preventive services with no cost sharing a one percentage point increase in the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for those services. As of January 30, 2014, ten states (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Kentucky, Nevada, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, and Wisconsin) had submitted State Plan Amendments (SPA) to cover all required preventive services, and eight SPAs had been approved.14

Extension of Dependent Coverage to Young Adults

The ACA extends dependent coverage to young adults up to age 26 beginning in September 2010. This provision allows young adults to remain on their parents’ health plans until they turn 26. Young adults can qualify for this coverage even if they are no longer living with a parent, are not a dependent on a parent’s tax return, or are no longer a student. While it is difficult to assess the effect of this dependent coverage provision independent of other factors, analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey indicates that 3.1 million young adults had gained coverage by December 2011.15

Controlling Premium Growth

Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Requirements

The MLR provisions in the ACA limit the amount of premium dollars insurers can spend on administration, marketing, and profits. They require most health insurers in the small group and individual market to spend at least 80% of premiums on health care claims and quality improvement. Health insurers in the large group market face a higher standard and must spend at least 85% of premiums on health care claims and quality improvement. Insurers were required to begin reporting MLRs in August 2011. Insurers not meeting the thresholds must issue rebates to consumers annually, beginning in August 2012. In the case of employer-sponsored plans, in which the cost of the premium is shared between employers and employees, insurers must provide a rebate to employees that is proportionate to their share of the premium.16

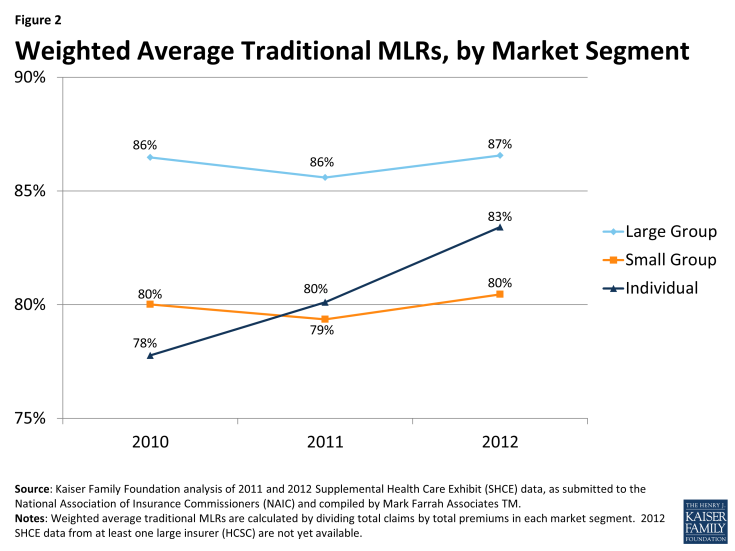

Insurers issued rebates totaling $519 million across all markets in August 2012 and $332 million in 2013. The drop in rebates in 2013 suggests that insurers were coming closer to meeting the MLR thresholds. Analysis of insurer data indicates this is the case. While most plans sold in the large and small group markets were already in compliance with the MLR requirements before the law went into effect, in the individual market, fewer than half of plans were in compliance. Since implementation of the law, the MRLs in this market have increased (Figure 2). The full impact of the MLR goes beyond just the rebates and includes the savings consumers experience from lower premiums than what would have been charged had the MLR provisions not been in place. While it is difficult to assess the full impact of the MLR provisions, an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation suggested that MLR savings to consumers totaled $1.2 billion in 2011 and $2.1 billion in 2012, with most of the savings resulting from lower premiums.17

Premium Rate Review

The ACA creates new standards for the review of premium rate increases proposed by insurers in the individual and small group markets to ensure the increases are based on accurate and verifiable data and are reasonable. While many states had rate review programs in place prior to the ACA, these programs were variable and set different standards for review. The ACA established minimum standards for an effective rate review program, permits federal regulators to review rates in states that do not have effective programs, and requires states or the federal government to review premium rate increases of 10% or more beginning September 2011. As of April 2014, 46 states and DC were deemed to have effective rate review programs in place. The five states without an effective program are Alabama, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming.18

An analysis of rate filings before and after the rate review requirements went into effect suggests these programs have had an impact on premiums. The premiums that went into effect in 2011 were, on average, 20% lower than the rates requested by insurers, though there were differences across states and markets.19 In addition, early evidence indicated that insurers were submitting fewer rate increases above the 10% threshold, and rate requests above the 10% threshold were more likely to be denied, reduced, or withdrawn following implementation of the new requirements in September 2011.

Risk Adjustment, Reinsurance, and Risk Corridors

The ACA includes three provisions designed to promote premium stability during the early years of ACA implementation. Changes in the insurance market—guarantee issue, rate restrictions and new subsidies available in the Marketplaces—make it easier for people with high health needs to purchase coverage. This possibility for adverse selection—when a disproportionate number of people with high health needs enroll in a plan—creates uncertainty for insurers. To encourage insurers to participate in the new Marketplaces and to compete on the basis of quality and value, rather than avoiding high risk enrollees, the ACA includes three premium stability programs: risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors, collectively known as the “three Rs”. Risk adjustment is a permanent program that transfers funds from insurers with lower risk enrollees to plans with higher risk enrollees. The temporary reinsurance program uses payments from all health insurance issuers and self-insured plans to partially offset the expenses for high-cost enrollees. The risk corridors program protects insurers against large losses by limiting insurers’ gains and losses beyond an allowable range.20 While the risk adjustment and reinsurance programs are required to be budget neutral, the risk corridor program is not. As a result, the risk corridor program has generated some controversy, with some critics characterizing the program as a bailout to insurers.

Health Plan Benefit Design

The ACA makes significant changes to health plan benefit design, setting uniform standards for covered benefits and cost sharing in the individual and small group markets. The ACA requires all non-grandfathered plans in the individual and small group markets, including those sold both inside and outside the Marketplaces, to cover ten categories of essential health benefits.21 These categories include:

- Ambulatory patient services

- Emergency services

- Hospitalization

- Maternity and newborn care

- Mental health and substance use disorders, including behavioral health treatment

- Prescription drugs

- Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

- Laboratory services

- Preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

- Pediatric services, including vision and dental care

Rather than establish a uniform benefit package to be offered by all plans, regulatory guidance required states to select an EHB benchmark plan that would define the essential health benefits that must be offered by plans in the state. Any benefits covered by this benchmark plan would be considered an essential health benefit. In addition, any limits on amount, duration, and scope of benefits would be included in the definition of the EHB.22 States had to select the benchmark plan by December 26, 2012 from among the following ten plans operating in the state: the three largest small group plans, the three largest state employee health plans, the three largest federal employee health plan options, or the largest HMO offered in the state’s commercial market. If a state did not recommend a benchmark plan, the default benchmark was the largest small group plan in the state. The majority of states (45) selected or defaulted to a small group plan, while four chose the largest commercial HMO, and two selected a state employee plan.23

If a state’s EHB benchmark plan did not include services in all of the required benefit categories, states were required to identify supplemental coverage to complete their EHB benchmark packages. Except for habilitative services, the benchmark plan could be supplemented by adding benefits for any missing categories from another benchmark plan. For habilitative services, states had the option to define the services to be included in that category or, if they chose not to make that determination, insurers were required to provide parity with rehabilitative services or define which habilitative services to cover and report to HHS.

Special rules govern coverage for abortion services. Abortion services are explicitly excluded from the list of essential health benefits that all health insurance plans are required to offer. No health plan is required to cover abortion services. States may allow private insurers to offer a plan in their state Marketplace that includes coverage of abortions beyond what is allowed under federal law (to save the life of the woman and in cases of rape and incest); however, premium payments must be segregated into two separate accounts – one for the value of the abortion benefit and one for the value of all other services. States may also prohibit coverage for any abortions by all plans, and at least one plan within a state Marketplace must offer coverage that excludes abortions outside those permitted under federal law.24

Plans sold in the Marketplaces and in the individual and small group markets must also fit into one of four metal tiers defined by their actuarial value (AV), which is the share of health costs covered, on average, by the plan. The four metal tiers and their AV are:

- Bronze: 60% AV

- Silver: 70% AV

- Gold: 80% AV

- Platinum: 90% AV

Insurers have flexibility to alter the cost-sharing features within metal tiers, for example setting deductibles at different levels or applying copayments instead of coinsurance, as long as the overall AV of the plan meets the required percentage.25

The ACA establishes a limit on the amount of cost-sharing consumers can be expected to pay for services covered by the plan. Once this overall limit is met, the plan must cover 100% of remaining health care costs for the year. The maximum out-of-pocket limit for 2014 was set at $6,350 per individual and $12,700 per family. These limits increased to $6,600 per individual and $13,200 per family in 2015. The out-of-pocket limits are lower for those with incomes below 250% FPL who are eligible for cost-sharing reductions. They drop to $2,250 per individual and $4,500 per family for those with incomes 100-200% FPL and to $5,200 per individual and $10,400 per family for those with incomes 200-250% FPL.

While the goal of the benefit changes enacted by the ACA was to improve the adequacy of coverage offered to consumers, particularly in the individual market, many people have faced disruptions because their plans were canceled, either because the plans did not comply with the new ACA requirements or because insurers chose not to continue offering the plans. Estimates from the Urban Institute indicate that about 2.6 million people had their plans canceled because the plans did not meet the ACA requirements and another 840,000 had plans canceled for other reasons.26 Many consumers whose plans were canceled were able to find comparable coverage through the Marketplaces or in the individual market outside the Marketplaces, though some had to pay more for the coverage. According to the findings from the Kaiser Survey of Non-Group Health Insurance Enrollees, of respondents who switched from non-compliant to compliant plans, similar shares reported paying higher or lower premiums for the new coverage (39% vs. 46%). However, plan switchers were less likely to report being satisfied with the plan costs and less likely to perceive their coverage as a good value, perhaps because about half of plan switchers reported having their previous plan canceled.27