The Coverage Provisions in the Affordable Care Act: An Update

Expanding Coverage

Health Insurance Marketplaces

The ACA creates new health insurance Marketplaces (also referred to as Exchanges) where individuals and small businesses can purchase insurance. Marketplaces are designed to create a more organized and competitive market for health insurance by offering a choice of health plans, establishing common rules regarding the offering and pricing of insurance, and providing information to help consumers better understand the options available to them. The Marketplaces serve individuals and small businesses (the Marketplace for small businesses is called the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP)). Coverage through the Marketplaces is available to nearly all U.S. citizens and legal resdients (undocumented immigrants and those who are incarcerated are not permitted to buy coverage in the Marketplaces), though financial assistance is only available to those meeting income and other requirements. Plans sold through the Marketplaces must meet certain standards and must be certified as Qualified Health Plans (QHPs).

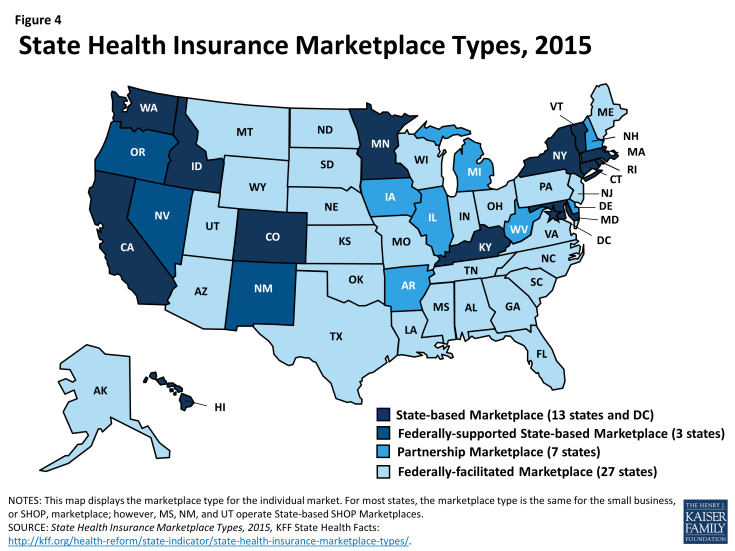

States approaches to the Marketplaces differ. The ACA envisioned that all states would implement State-based Marketplaces (SBMs); however, political opposition among Republican Governors and state legislatures led many states to opt for a Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM). Thirty-four states rely on a Marketplace fully run by the federal government, while seven states adopted a hybrid approach (a State-Partnership Marketplace) in which the states assume some Marketplace responsibilities, including plan management and consumer assistance. In all, 17 states have established SBMs, with 14 of these fully run the states. Three SBMs (Nevada, New Mexico, and Oregon) that struggled to establish functional websites through which consumers could apply for and enroll in coverage have chosen to use the federal healthcare.gov portal for 2015 (Figure 4).

To assist states in setting up the Marketplace, the ACA provided federal funding to states through Exchange Planning and Establishment grants. This funding was available to states through December 2014. Nearly $5 billion in funding was provided to states through these grants.1

One of the most significant challenge states and the federal government have faced in establishing the Marketplaces has been building the online portal or website through which individuals and small employers can apply for and enroll in coverage. Last year, healthcare.gov, the federal website, launched with nearly catastrophic problems. Many state websites also experienced problems and while many of these issues were resolved before the end of the open enrollment period, websites in several states never worked well and have since been scrapped. During the second open enrollment period, the federal website and most state websites were free of the serious problems encountered last year.

Health insurance Marketplaces were marked by volatility in first two years of operation. Most Marketplaces offered consumers a choice of plans in the first year, and premiums overall were lower than expected. In year two, new insurers entering Marketplaces in many states are enhancing competition and increasing consumer choice in those areas. However, decisions by some insurers to leave certain markets have left many consumers with the need to find new coverage and fewer coverage options.2 Overall, premium growth in 2015 was modest, but it masked large variation across states, from increases as large as 28% in Alaska and 18% in Minnesota to declines of 15% and 25% in Colorado and Mississippi, respectively.3 As insurers adjust their premium pricing strategies, some consumers are facing higher prices to remain in the same plan.

Premium Tax Credits and Cost Sharing Reductions

Premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions are available through the Marketplaces to make coverage more affordable for qualifying individuals. Premium tax credits are available to U.S. citizens and legally residing immigrants who have income between 100% and 400% FPL and who do not have access to affordable coverage through an employer or public coverage (Medicaid, CHIP, or Medicare). Married consumers must file taxes jointly in order to qualify. The tax credits work by limiting the amount consumers must pay for coverage to a percentage of their income. In 2015, the required premium contributions range from 2.01% of income for those with income 100-133% FPL to 9.56% of income for those with incomes 300-400% FPL.4 The tax credit amounts are tied to the second-lowest cost Silver plan (the benchmark plan), though consumers may use these tax credits to purchase less or more expensive plans.

Cost sharing reductions are available to individuals eligible for premium tax credits with incomes between 100 and 250% FPL. The cost sharing reductions lower deductibles, copayments, and other out-of-pocket costs. They work by increasing the actuarial value of Silver level plans from 70% to 94% for those with incomes 100-150% FPL, 87% for those with incomes 150-200% FPL, and 73% for those with incomes 200-250% FPL. To take advantage of the cost sharing reductions, consumers must purchase a Silver plan.

Consumers who are eligible for tax credits may receive advance payment of those tax credits based on their projected income for the coverage year; however, they will need to reconcile receipt of the advance payments when they file their taxes. Consumers who received advance payment of premium tax credits in 2014 are reconciling those payments for the first time this year. Consumers who received payments that were too high based on their annual income for the year will be required to repay some or all of the excess payments. Limits are placed on repayment amounts for those with incomes less than 400% FPL. In addition, an exception is made to the repayment requirements for consumers who received advance payment of the tax credits during the year but whose income later fell below Medicaid eligibility levels, or below the poverty level, by the end of the year. These consumers are not required to repay the payments they received. Consumers who received payments that were too low based on their annual income will receive a refund.

Due to what is referred to as the family glitch, many working low-income families for whom the cost of family coverage through an employer is not affordable are not eligible to access subsidized coverage in the Marketplace. Under the ACA, premium tax credits in the Marketplaces are not available to those who have an affordable offer of coverage from their employer. An offer is considered affordable if the employee share of the premium for single coverage costs less than 9.5% of the employee’s income. This definition applies even if the employee needs to purchase family coverage that may cost more than 9.5% of income. Estimates suggest that as many as 3.9 million dependents are excluded from accessing premium tax credits that would lower their cost of coverage.5 While these dependents are exempt from any penalties related to not having insurance, without an affordable coverage option, many may forego insurance.

Cost sharing in Marketplace plans is high, but cost sharing subsidies meaningfully reduce the out-of-pocket burden for many low and modest-income consumers. In general, consumers enrolling in plans in the Marketplace face high out-of-pocket costs when they access health services. Overall, across the states using healthcare.gov, deductibles for Silver plans averaged $2,556 and the average out-of-pocket limit was $5,826. These amounts were reduced in plans that applied the cost sharing reductions (CSR plans). Deductibles averaged $2,077 in CSR73 plans, $737 in CSR87 plans, and $229 in CSR94 plans while out-of-pocket costs were capped on average at $4,624 in CSR73 plans, $1,692 in CSR87 plans, and $881 in CSR94 plans.6 Particularly for those eligible for CSR94 and CSR87 plans, these reductions in cost sharing amounts can help to alleviate the financial burden of accessing needed health care services.

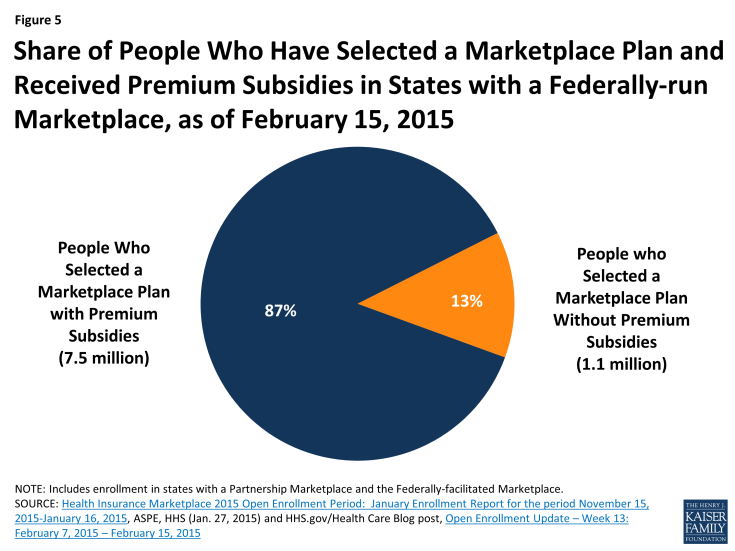

A decision in the case, King vs Burwell, currently before the Supreme Court, will determine whether the federal government has the authority to continue providing subsidies to consumers in states that do not have a state-run Marketplace. The plaintiffs in the case argue that a strict interpretation of the language of the ACA prohibits subsidies in states that do not have a Marketplace “established by the state.”7 A ruling for the plaintiffs in this case would invalidate premium tax credits and cost sharing reductions for consumers in the 34 states that rely on the Federal Marketplace or operate a Partnership Marketplace. Subsidies in the three SBM states that rely on the healthcare.gov web portal may also be at risk. As of February 15, 2015, there were over 7.5 million people in the 34 states whose subsidies could be at risk. A ruling by the Court in this case is expected in June 2015 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Share of People Who Have Selected a Marketplace Plan and Received Premium Subsidies in States with a Federally-run Marketplace, as of February 15, 2015

Basic Health Program

To date, only Minnesota has adopted the Basic Health Program (BHP) option, which allows states to create an alternative coverage program for adults with income between 133 and 200% FPL who would otherwise be eligible for coverage through the Marketplace. The BHP provides states with the option of offering coverage that is more affordable and/or more comprehensive than what would be available to consumers in the Marketplaces. States have flexibility in designing this coverage, but it must be at least as comprehensive and affordable as subsidized coverage in the Marketplaces. To finance the BHP, the federal government pays states 95% of what BHP enrollees would have received in Marketplace subsidies.8 States can implement BHP beginning in 2015. So far, only states that offered more comprehensive Medicaid coverage prior to the ACA are considering adopting the BHP.

Outreach and Enrollment

Marketplaces are required to establish and finance Navigator programs to conduct outreach and provide enrollment assistance to consumers. According to a survey of assister programs nationwide, a total of 28,000 assisters provided enrollment assistance to over 10 million consumers during the 2014 open enrollment period.9 These assisters have proven instrumental in educating consumers with limited experience purchasing private insurance and who face challenges, such as language barriers and lack of access to the internet, to applying for and enrolling in coverage. While states running their own Marketplaces have been able to use federal grant funds to support robust assister programs during the first two years, support for Navigators in FFM states has been more limited.10 Future funding for assisters is a concern in both state Marketplaces and the FFM.

At the end of the first open enrollment period, over eight million people had selected a Marketplace plan. Despite a slow start to enrollment due to website problems that hindered early enrollment, a surge in sign-ups during the last two weeks of the open enrollment period pushed enrollment above eight million. By October, 6.7 million people were enrolled and paying premiums, a fall-off that was somewhat expected as people’s situations changed and difficulties arose in paying premiums.

As of February 15, 2015, over 11.6 million people had signed up for coverage through the Marketplaces. While the second open enrollment period officially ended on February 15, 2015, extensions were granted in many states for those who were “in line” on the closing date. As a result, the total number of people signing up for coverage in 2015 will increase. Based on the preliminary enrollment data from states using healthcare.gov, about 52% of those enrolling in coverage in 2015 were new to the Marketplace, while 42% renewed their coverage from 2014. Less than half of consumers renewing coverage were automatically reenrolled in their current plan, while 53% of renewing consumers returned to the Marketplace and selected a new plan.11

Medicaid Expansion

The ACA sought to fill one of the most notable gaps in Medicaid’s role as a source of coverage for the low-income population— the exclusion of adults without dependent children no matter how poor, unless a state obtained a waiver to provide them coverage (and few states had such waivers). The ACA intended to remove the categorical eligibility requirements for Medicaid coverage stemming from its welfare heritage and convert Medicaid coverage to be based on income— establishing a national minimum income eligibility level effectively at 138% FPL in all states. This standard would apply mostly to adults as all states cover children to substantially higher levels through Medicaid and CHIP with median eligibility at 255% of poverty. The expansion population is 100% federally financed in 2014-2016 with the federal match phasing down to 90% in 2020 and thereafter. Consistent with previous Medicaid policy, undocumented and recent lawfully present immigrants remain excluded from enrolling in coverage.

As enacted, the ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to adults with income at or below 138% FPL, although this core provision was effectively made a state option by the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the ACA. However, other eligibility changes in the law were unaffected by the Court’s decision, including establishing a new minimum coverage level of 138% FPL for children of all ages in Medicaid, helping to align Medicaid coverage across children. The ACA also changed the method for determining financial eligibility for Medicaid for children, pregnant women, parents, and adults and CHIP to a standard based on modified-adjusted gross income (MAGI). This new approach, effective January 1, 2014, is intended to prevent gaps in coverage between programs by aligning with the method for determining eligibility for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage.

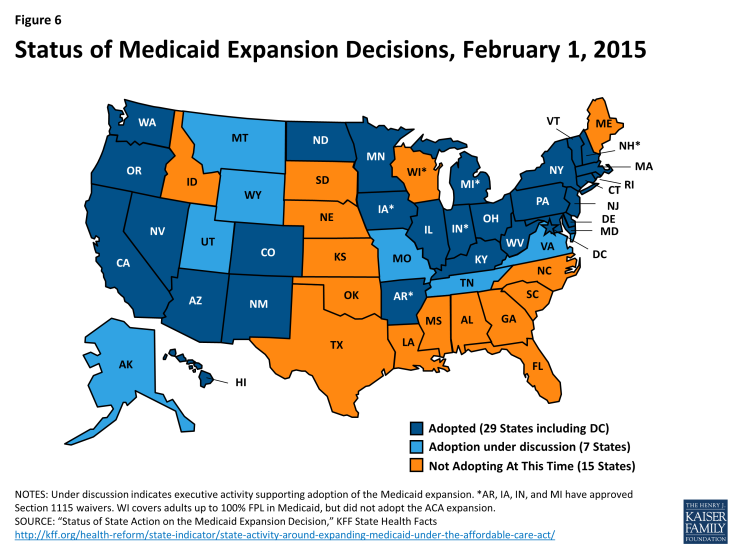

As of February 2015, 29 states and the District of Columbia have implemented the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults (Figure 6). Most states expanded Medicaid consistent with federal rules and options provided under the ACA, but five states (Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania) obtained Section 1115 waivers to implement the expansion in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law (the Governor of Pennsylvania recently announced the state would not proceed with implementing the waiver, but would instead expand Medicaid through the State Plan Amendment process).12 Notably, Arkansas has implemented the expansion with a waiver that allows it to implement a mandatory premium assistance program where the state enrolls the expansion population into QHPs in the Marketplace. Other states have used waivers to impose premiums for individuals with incomes between 100 and 138% FPL or to add healthy behavior incentives to coverage.

Medicaid Coverage Gap

Large gaps in coverage persist for parents and other low-income adults in the 22 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid since Medicaid eligibility levels for parents remain very low and childless adults remain ineligible for full Medicaid benefits in all but one of the non-expansion states. Among the non-expansion states, the median eligibility level is 46% FPL for parents and 0% for other adults, compared to 138% FPL for parents and adults in expansion states.

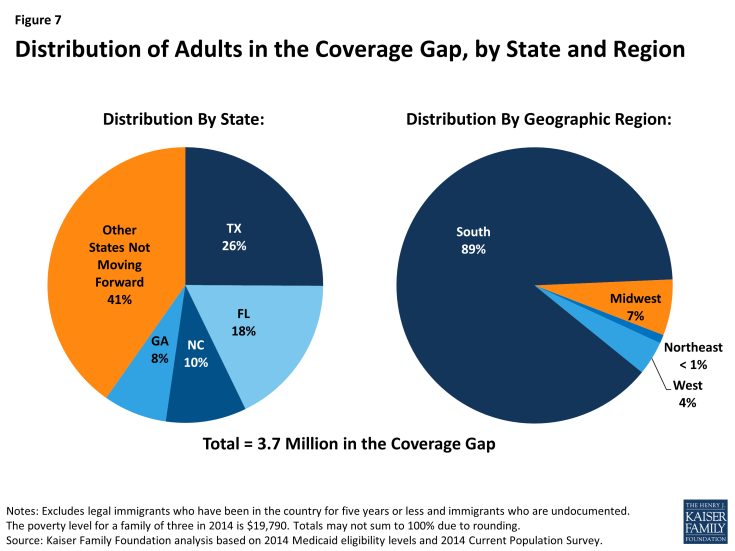

As a result of these limited eligibility levels, 3.7 million poor uninsured adults fall into a coverage gap because they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid and too little to qualify for subsidies for Marketplace coverage, which begin at 100% FPL.13 Because the ACA was enacted assuming the Medicaid expansion would go forward in all states and everyone below the poverty level would be covered, the law only provided access to subsidies through the Marketplace for individuals above the poverty level up to 400% FPL. Thus, those individuals between 100-138% FPL, who would have been covered by Medicaid if the state expanded, are able to access subsidized coverage in the Marketplace but those below poverty are ineligible for subsidies. Of the 3.7 million adults in the coverage gap, nearly 90% live in the south and over half are Black or Hispanic (Figure 7).

Even in states that do expand Medicaid, undocumented immigrants and many recent lawfully present immigrants will remain ineligible. Because many uninsured non-citizens are in low-income working families, many are in the income range to qualify for the ACA Medicaid expansion. However, under federal rules, undocumented immigrants may not enroll in Medicaid. Many lawfully present non-citizens who would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid remain subject to a five-year waiting period before they may enroll, and some groups of lawfully present immigrants remain ineligible regardless of their length of time in the country.

Medicaid Enrollment

Medicaid enrollment has grown under the ACA. Enrollment data show that as of December 2014, Medicaid and CHIP enrollment has grown by over 10.7 million since the period just prior to the beginning of the initial open enrollment period for the Marketplaces in October 2013.14 This change represents an 18.6% increase in enrollment over the period across all states. Enrollment increases were higher (27%) among states that chose to expand Medicaid eligibility under the ACA, compared to states that had not expanded (7%), suggesting that the Medicaid expansion is contributing to greater enrollment growth. However, some who are eligible remain unenrolled due to limited awareness about the Medicaid program and their eligibility or other enrollment challenges.

Streamlining Application and Enrollment Processes

The ACA also enacted sweeping changes to streamline and modernize application, enrollment, and renewal processes in Medicaid and CHIP and coordinate with the Marketplaces which all states must implement regardless of their Medicaid expansion decisions. Together these processes are intended to achieve the ACA’s vision to provide “no wrong door” access to all health coverage options, minimize the paperwork burden on consumers and state agencies, and enhance the consumer experience.15 States must provide multiple options for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person, using a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. In addition, states must seek to rely on electronic data to verify eligibility criteria and renew coverage.

Impact on the Uninsured

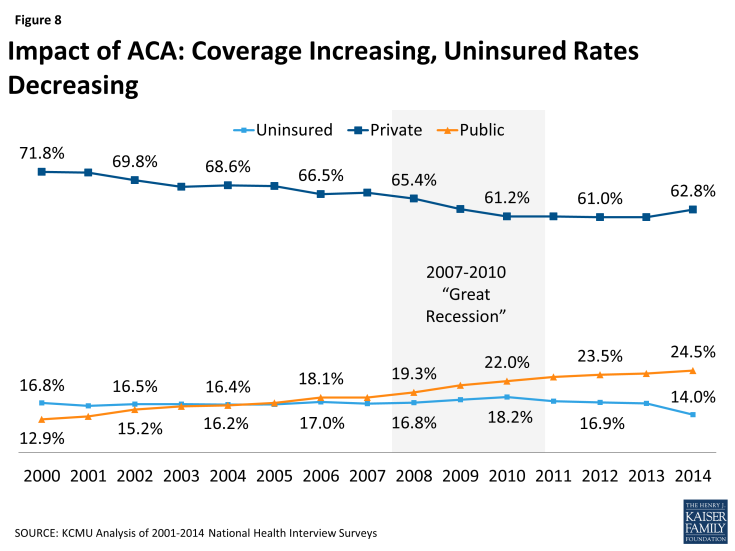

New coverage options available through the ACA have resulted in many uninsured gaining coverage. Increased coverage through employers, the Marketplaces, and Medicaid is bringing down the uninsured rate. Data from the National Health Interview Survey shows a drop in the uninsured rate among the non-elderly from 16.6% in 2013 to 14.0% in the second quarter of 2014, with the most significant decline for the low-income and minority uninsured population (Figure 8).16 In addition, a survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation indicates 11 million uninsured adults gained coverage in 2014.17 Other poll data show similar results.

The uninsured rate is dropping more precipitously in states that have embraced the ACA’s coverage expansions. Data from the National Health Interview Survey indicate that there was a greater decline in the uninsured rate in states that are expanding Medicaid. Among states adopting the Medicaid expansion, the uninsured rate dropped by 4.3 percentage points from 18.4% in 2013 to 14.1% through the second quarter of 2014. In contrast, the uninsured rate dropped by only 2.5 percentage points in states not adopting the Medicaid expansion, from 22.7% in 2013 to 20.2% through the second quarter 2014.18 Other evidence from the Gallup Healthways Well-Being Index reveals the largest reductions in the uninsured have been in Arkansas and Kentucky.19