Supporting Work without the Requirement: State and Managed Care Initiatives

Background

KFF analysis shows that 63% of Medicaid adults1 are already working, many in jobs that do not offer health insurance, and that those who are not working often face barriers to employment.2 Caregiving responsibilities, illness or disability, and school attendance are the most common reasons that Medicaid enrollees report for not working, while those in better health and with more education are more likely to be working. Among Medicaid adults who are working, the majority (53%) work full-time for the entire year. These enrollees may be eligible for Medicaid in expansion states if they are working low-wage jobs, while those working in non-expansion states could earn enough to become ineligible for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for Marketplace subsidies (which require income of 100% to 400% of the poverty level), while also not necessarily receiving health coverage through their jobs. Only about four in ten working Medicaid adults have access to employer-sponsored insurance.

CMS issued guidance in January 20183 for state Medicaid waiver proposals that condition Medicaid eligibility on work and reporting requirements, and several states have received approval for or are pursuing these waivers.4 The administration says that such policies are designed to address health determinants, such as employment, to improve health outcomes.5 The waivers seek to promote work by making individuals’ health coverage contingent on meeting certain requirements – like reporting minimum monthly work hours – versus supporting employment through voluntary efforts that focus on identifying barriers to work and facilitating links to services that address those barriers. The January 2018 CMS guidance notes the importance of employment supports while stating that such support services are not eligible for federal Medicaid funds.

The experience of Arkansas, the first state to implement a Medicaid work requirement, reveals widespread coverage losses and little measurable increase in employment as a result of the requirement. The work requirement phased in beginning in June 2018, and state data revealed that, by December 2018, over 18,000 Medicaid enrollees had been disenrolled6 from the program for failure to comply with the new requirements, with most of this coverage loss resulting from failure to report activities. By February 2019, only 11% of those enrollees had regained coverage in Medicaid. While the state did not track whether enrollees began work activities in response to the requirement, an independent study found no significant change in employment in response to implementation of the requirement.7 Arkansas’s waiver that authorizes its work requirement was set aside by a federal court in March 2019, suspending the requirement’s implementation; an appeal is currently pending.

How can Medicaid support employment without a waiver?

Medicaid supports employment by providing affordable health coverage, which helps low-wage workers get care that enables them to remain healthy enough to work. Research has shown that access to affordable health insurance and care promotes individuals’ ability to obtain and maintain employment. For example, in studies on the effects of Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan before CMS approved work requirements in these states, previously unemployed individuals reported that Medicaid enrollment made it easier for them to seek employment, while employed individuals reported that enrollment allowed them to perform better at work or made it easier to continue working.8 A study of Montana’s Medicaid expansion, including the state’s voluntary Medicaid work support program (HELP-Link), found an increase of four to six percentage points in labor force participation among low-income, non-disabled adults ages 18-64 following expansion, compared to higher-income non-Medicaid Montanans and to the same population in other states.9

Medicaid also supports work by providing eligibility pathways for individuals with disabilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) that support employment and target barriers to work.10 Under Medicaid buy-in programs, states can elect to cover people with disabilities who choose to work, supporting their participation in the workforce without carrying the risk of coverage loss. The median income limit for this pathway is 250% FPL, well above the income limit for other coverage groups.11 HCBS help individuals with disabilities with self-care and household activities to enable them to live independently in the community. These services can support work for individuals with disabilities who choose to work by addressing physical, mental health, or cognitive needs that create barriers to employment.12 States can also provide voluntary supported employment services to targeted Medicaid populations, such as pre-employment services (e.g., employment assessment, assistance with identifying and obtaining employment, and/or working with employer on job customization) and employment sustaining services (e.g., job coaching and/or consultation with employers).13

State Medicaid programs have limited flexibility to support employment for nonelderly Medicaid adults eligible through non-disability pathways. The transitional medical assistance (TMA) pathway allows low-income parents who lose eligibility for cash assistance due to earned income to remain eligible for Medicaid for at least six months and, at state option, up to a year if their earnings increase through work and exceed the Medicaid eligibility threshold. Although states are not able to use federal Medicaid funds to pay the direct costs of non-medical services that address social needs (e.g., housing, food assistance, employment supports), states can link enrollees to social service programs through case management or targeted case management benefits. In addition, many states that contract with Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to deliver services to enrollees are leveraging MCO contracts to promote strategies to address enrollee social needs. According to a KFF survey of state Medicaid programs14 released in October 2019, about three-quarters of the 41 managed care states will require MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs, provide enrollees with referrals to social services, or partner with community-based organizations in FY 2020. Under federal Medicaid managed care rules, health plans also have some flexibility to pay for non-medical services directly, but it is currently unclear how frequently plans engage in funding these types of activities, as states have provided little guidance to health plans in this area to date.15,16

In the spring of 2019, CMS released further guidance17 on implementing, monitoring, and evaluating Medicaid work requirement waivers, which contains strategies that states interested in developing voluntary work support programs could adopt as well. The guidance includes a detailed implementation plan template18 with a section on establishing beneficiary supports and modifications, requiring states to describe in detail how they will provide supports to beneficiaries (e.g., transportation, child care, language) to ensure that they are able to meet work requirements. Although CMS developed the guidance for states pursuing policies to condition coverage on meeting work and reporting requirements, it provides numerous examples of practical strategies that state Medicaid programs interested in developing voluntary work support initiatives could implement as well.

What are states and health plans doing to support work for Medicaid enrollees who qualify through non-disability pathways?

While most Medicaid adults are already working, some states have launched initiatives to support employment for Medicaid enrollees who qualify for Medicaid through non-disability pathways, without making employment a condition for eligibility. While states like Arkansas and Indiana offered voluntary employment referral programs for Medicaid expansion enrollees before implementing work requirements, those programs relied on general enrollee notices rather than targeted outreach and follow-up and saw limited participation.19 Other states have taken a more proactive approach to maximize the success of their voluntary work support programs, incorporating intensive targeted outreach and case management services. These states — Montana, Louisiana, and Maine — provide examples of work support activities that provide Medicaid expansion enrollees with targeted employment-related services and trainings and/or connect them with appropriate existing state and federal workforce programs. In addition to state agencies, some MCOs have developed work support initiatives in an effort to address their members’ social determinants of health.

Montana

Montana provides a leading example of a state that supports employment for Medicaid enrollees without conditioning eligibility on work. While Montana did submit a proposed work requirement waiver amendment to CMS in August 2019 as a condition of continuing its Medicaid expansion — and has since delayed the implementation of the requirement20 — the state has several years of experience with providing voluntary work supports to expansion enrollees with identified barriers to work. As part of the 2015 “Health Economic Livelihood Partnership” (HELP) legislation that established the state’s ACA Medicaid expansion, Montana created “HELP-Link,” a free voluntary workforce support program for eligible expansion adults. HELP-Link, which launched on January 1, 2016, provides individualized career planning and training assistance, and participation in the program may help individuals who fall behind in paying Medicaid premiums to maintain coverage, as nonpayment can otherwise result in disenrollment.21 Montana’s stated objective for HELP-Link is to “improve the employment and wage outcomes of individuals enrolled in certain types of Montana Medicaid, with the goal of reducing clients’ reliance on Medicaid for health insurance and improving Montana’s workforce.”22

Since states cannot receive federal Medicaid funds for employment support services for Medicaid enrollees, Montana administers the HELP-Link program with state funds. The state’s Department of Labor and Industry (MTDLI) operates the HELP-Link program in partnership with Montana’s Department of Health and Human Services. Montana allocated state workforce training funds specifically for HELP-Link, which offers more intensive one-on-one services and case management than other MTDLI programs. In serving Montana Medicaid enrollees found eligible for HELP-Link, the state often leverages other federally funded workforce programs to help stretch HELP-Link dollars. Of the roughly 32,000 Montana Medicaid expansion adults who received career or workforce training services through an MTDLI program from the launch of HELP-Link through June 30, 2019, 4,257 people received services with targeted HELP-Link funds.23 HELP-Link clients can also co-enroll in multiple workforce programs. The state appropriated $1.8 million for HELP-Link for the first year and a half of the program, spent $1.6 million in SFY 2018, and allocated almost $889,000 for SFY 2019, supplementing that initial SFY 2019 allocation with $50,620 in additional state funds.24 Of total HELP-Link spending, 53% went directly to participants and 32% to case management and other client services.25 HELP-Link was initially a pilot program scheduled to expire in July 2019, but the 2019 state legislation that required submission of the work requirement waiver appropriated $3.5 million to extend the program through SFY 2021, although some of this funding will be used to create another state workforce program.26

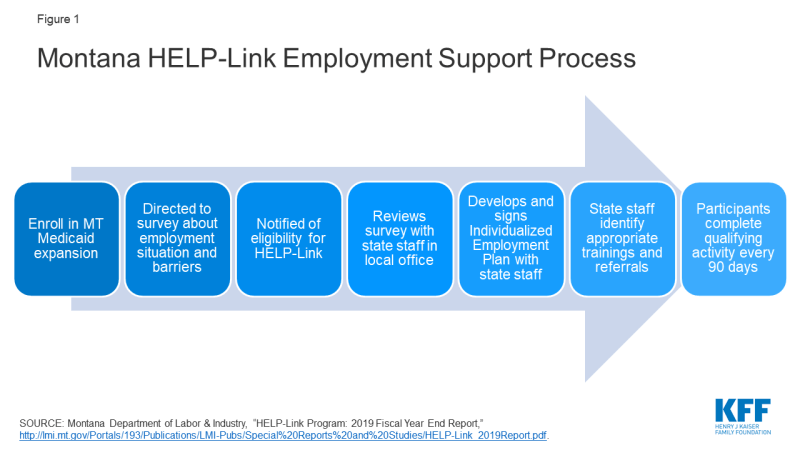

The HELP-Link program uses a screening survey, employment support services, and referrals to identify enrollee goals and needs and connect them to the appropriate resources (Figure 1). As soon as Montanans enroll in Medicaid expansion, they are automatically directed to a state website to complete a survey about their employment status and barriers to work and invited to participate in state workforce programs. Individuals can also complete the survey in person in a Job Service Montana office. If found eligible for HELP-Link, individuals must meet in person with Job Service Montana staff to develop an Individualized Employment Plan that serves as a step-by-step checklist that can assist HELP-Link participants in achieving their employment goals. The state acknowledges that this in-person interview can be a barrier to participation for individuals who live in rural or reservation areas or far from a Job Service office, although the state notes that participants may request a phone appointment if “extenuating circumstances” prevent an in-person visit.27

HELP-Link assists participants across five domains, which require different levels of resources. The domains include employment services and career planning (e.g., resume assistance, mock interview practice, local job opportunity information); workforce and educational training; work-based learning (including wage subsidies for on-the-job training); supportive services (financial assistance to address specific barriers); and referrals to other service providers (e.g., for needs related to transportation, childcare, or domestic violence). Most HELP-Link participants receive less resource-intensive career services, which could include referrals to other federal workforce programs, while a smaller group of participants receive support for educational and job training programs, which could take several years to complete. The level of HELP-Link funds required for different types of services varies by resource intensiveness. For example, the majority of SFY 2019 HELP-Link funding went to employment-related training and support ($1,703 per client for 250 clients), while the state spent $176 per participant on case management services for 1,159 participants. Montana has noted that this tiered support system, in which individuals with greater need receive more intensive program services, may serve as a cost-effective method of operation.28

To address participant barriers to work such as lack of transportation, housing, internet access, or childcare, Montana Job Service staff can use HELP-Link funds both to meet these needs directly and to refer participants to other state and federal programs or community-based organizations that provide appropriate resources. HELP-Link stresses the provision of customized and flexible support to its participants, tailored to meet individual needs. For example, HELP-Link funds can cover qualifying individuals’ enrollment in educational or training programs that can help them attain credentials that further their careers. HELP-Link funds can also cover supportive services, providing financial assistance to help resolve barriers to employment (e.g., to pay for gas, auto repairs, or job-related equipment). To remain eligible to receive work supports through HELP-Link after signing their employment plans, participants must complete a qualifying workforce planning, training, or job search activity every 90 days.

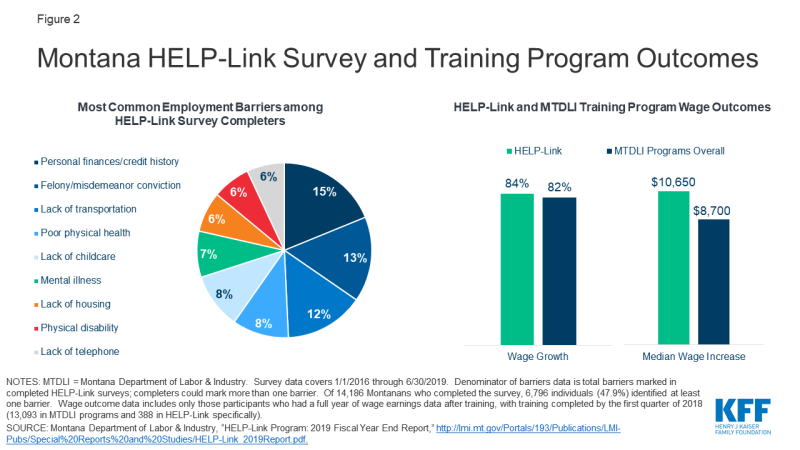

Outcomes from the first two years of HELP-Link implementation, alongside other MTLDI programs, reveal several common barriers to work, along with high rates of participant employment and wage growth after receipt of HELP-Link training (Figure 2). The most common barriers to employment for those individuals who completed the survey included personal finances and credit history; felony or misdemeanor conviction; lack of transportation, childcare, housing, or telephone access; poor physical health; mental illness; and physical disability. Because of limited HELP-Link funds, some Medicaid expansion enrollees received employment services through HELP-Link specifically, while others participated in other MTDLI workforce development programs. Wage outcomes for enrollees who participated in training activities varied according to whether the individuals received HELP-Link-funded training or training funded through MTDLI programs more broadly.29 Large shares of both those in MTDLI workforce programs overall and those who received the additional training resources and services available under the HELP-Link program saw wage growth among employed participants (82% and 84%, respectively). However, those receiving HELP-Link-funded services saw higher median wage increases a full year after completing training ($10,650, versus $8,700 for those participants in MTDLI programs overall).30 These outcomes include only participants who completed training by the first quarter of 2018 (388 in HELP-Link and 13,093 in MTDLI workforce training programs) and had a full year of wage earning data available after completion.31 The most common occupations pursued by HELP-Link participants include truck drivers, registered nurses, and personal care and service workers.

Louisiana

On a smaller scale than Montana, Louisiana has taken a local approach to voluntary Medicaid enrollee work supports. After Louisiana rejected legislation to condition Medicaid eligibility on work, the state invested in a pilot program to link certain Medicaid expansion enrollees with targeted work training programs through Louisiana Delta Community College (LDCC).32 Under the program, LDCC identifies a subset of unemployed and underemployed Medicaid recipients living in Ouachita Parish whom it considers able to benefit from the program, and LDCC and the Louisiana Department of Health (LDH) collaborate to conduct outreach to those individuals. Individuals who accept the invitation to enroll in the pilot program then participate in an intake process to identify work experience and interests, which leads to the formation of an individualized participant plan with the assistance of designated pilot staff members. Participants are then matched with tailored support services and enroll in select work training programs with assignment to an LDCC mentor. Support services may include job readiness and job search resources, while available training programs include those for occupations such as certified nurse assistants and environmental services technicians. The time that participants have to complete their programs will depend on the courses of study that they select.33 Public state documents do not specify the source of funding for this program, but the governing legislation establishes that a partnership of state agencies, led by the executive director of the Louisiana Workforce Commission, will design and administer the program.34

Maine

Maine provides another example of a state that has chosen to emphasize vocational training and workforce supports rather than impose a work requirement as a condition of eligibility in its Medicaid program. After Maine’s voters approved a 2016 ballot initiative to expand Medicaid (which did not include a work requirement), the governor in office at the time refused to adopt it and instead submitted a waiver request to CMS seeking approval of a work requirement. Once the current governor took office in early 2019, she adopted the voter-approved Medicaid expansion and chose not to accept the federal government’s terms for a work requirement,35 electing instead to increase the accessibility and use of existing state and federal programs devoted to work training.

Maine’s work support activities for both expansion and non-expansion Medicaid enrollees include collaborating with other state agencies and connecting enrollees to federal programs that address their employment and social needs.36 At a high level, the state’s governor directed the Commissioners of Labor and Health to coordinate their departments’ activities to maximize the accessibility of work-related opportunities to Medicaid enrollees, with the Commissioner of Health noting that access to health care is the first step in supporting employment. For example, the governor indicated that the state would take steps to ensure that its existing vocational training workforce programs, including those under public benefit programs such as TANF and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), are available to Medicaid enrollees “at every opportunity, while increasing access to needed services that will keep them in the workforce.” She noted that work mandates without appropriate employment supports would likely “leave more Maine people uninsured without improving their participation in the workforce,” and that “Maine believes that providing appropriate educational opportunities and vocational training, along with critical health care, is the most effective way to lift people out of poverty and into the workforce.” 37 While emphasizing cross-agency collaboration and maximization of existing funding to support work, the state does not specify whether new resources will be available for such efforts.

Managed Care Organizations

In addition to state-led initiatives, Medicaid managed care plans can take steps to connect their members with job services and employment, as well as other support services. In a 2017 survey of Medicaid MCOs, 77% of MCOs reported that they had undertaken activities in the previous year to address enrollee needs in housing, 73% in nutrition and food security, and 51% in education. The survey further shows that 31% of MCOs reported efforts in the previous year to address their members’ employment needs directly, and 52% reported offering social services, such as WIC application assistance and employment counseling referrals, to their members in the previous year. The scope and depth of plan activities in these areas were not clear from the survey responses.

Some states require MCOs to assist their members with addressing barriers to work and finding employment. For example, West Virginia’s managed care contracts require MCOs to refer members who seek information about workforce opportunities to local workforce offices for additional assistance.38 For members that have behavioral health or medical needs that interfere with their ability to establish employment, the MCO is required to enroll the member in care management and establish a care plan to address those barriers to work. Massachusetts also requires its MCOs to develop care plans for their members that address identified social needs, including employment.39

CareSource, which operates a program called JobConnect in Georgia, Indiana, and Ohio, provides direct employment assistance to its members. JobConnect is part of a larger CareSource initiative called Life Services, which focuses on social determinants of health, particularly for low-income members. JobConnect is a voluntary program that offers members the chance to work one-on-one with life coaches to identify personal strengths and areas of social need. Interested members first enroll in JobConnect by completing a Health Risk Assessment, calling or emailing CareSource, or being referred by a community partner.40 Personal life coaches then assess participants’ resources, skills, interests, and needs, and they connect participants with community partners that provide social services to address members’ barriers to work, such as food banks, transportation vouchers, and other public benefit programs like SNAP and TANF. JobConnect life coaches also link participants with employment opportunities by working directly with employers and connecting members with work support resources such as free computer classes. CareSource directly funds several other employment-related supports, including fee contributions for High School Equivalency exams and transportation to test preparation classes.41 In addition, CareSource offers such JobConnect services to non-member parents whose children are enrolled in CareSource.42 JobConnect has served 2,870 members since its 2015 inception and is 90% funded by CareSource and 10% from external grants. Outcomes for Life Services more broadly show 5,016 total community referrals, and 86% of members retaining employment.43 CareSource offers multiple lines of business, so the degree to which Life Services and JobConnect serve Medicaid enrollees specifically is unclear.

What common themes appear across voluntary Medicaid work support programs?

Across state and MCO voluntary employment support programs, several themes emerge. First, due to their voluntary nature, they all allow Medicaid enrollees to keep their coverage. The programs often take a targeted approach to the county, locality, or individuals that they serve, including a focus on identifying the specific barriers that may prevent a particular individual from working and providing services to address those barriers and support enrollees’ ability to work. These programs also often incorporate coordination among state agencies or public benefit programs, such as TANF and SNAP, as well as community-based organizations that can help meet enrollees’ needs. Finally, the most robust programs include high-touch referrals to these partners as well as follow-up to track enrollee progress.

State Medicaid agency and MCO employment initiatives customize their programs to the county or locality that they serve. For example, Louisiana’s program is designed to operate in a specific local context, with the express goal of replicability by and customization to other locales. Eligible participants are a subset of those in the Medicaid expansion population who reside in the state’s Oachita Parish and whom LDCC identifies as standing to benefit from work training. Similarly, CareSource’s JobConnect program draws its life coaches from the communities that they serve, allowing for greater connection with local resources and opportunities.

Voluntary employment support programs emphasize the importance of identifying individuals who are not working but currently are in a position to work, and then assessing and addressing their barriers to employment. For example, in Montana, the HELP-Link program begins with a formal assessment of participants’ personal barriers and challenges to employment or higher earnings. Job Service staff then analyze these assessments and connect the enrollees to personalized services that will address the barriers that they have identified. Such services can include childcare referrals for parents, help with resumes, or job training. MTDLI has conducted HELP-Link outreach with limited funds and focused resources on those who completed the survey or indicated interest in the program. This targeted outreach resulted in higher take-up for HELP-Link than other MTDLI programs. Similarly, Louisiana’s pilot program with LDCC includes an intake process that involves completion of a participant assessment tool and an individual participant plan.44 The assessment tool includes a participant’s work experience, skills, challenges, and interests, while the plan then establishes the support services and educational activities identified for that participant.

Voluntary employment support programs for Medicaid enrollees often involve coordination with other state agencies and programs, as well as community-based organizations, to connect enrollees with targeted services. For example, both Montana’s and Maine’s Medicaid agencies partner with their TANF and SNAP programs to connect Medicaid enrollees with work supports available through those programs. Both HELP-Link and JobConnect link participants with community-based organizations, such as local non-profit partners, that can assist them with needs such as financial counseling, food security, or internet service. Louisiana’s pilot program involves cross-agency collaboration, as the state’s Department of Health partners directly with LDCC to run the initiative.

HELP-Link and JobConnect also demonstrate the importance of high-touch referrals and follow-up to the success of their employment programs. After development of the individualized employment plan, state workforce consultants regularly follow up to help participants achieve the goals outlined in their plans. They employ a team approach designed to coach clients through a variety of applications and paperwork for training programs. If a participant’s barriers to work fall under the mission of another state agency or community-based organization, HELP-Link staff will refer that participant to the appropriate partner. After employers for specific jobs, the most common referrals are to the state’s workforce programs, as well as its Office of Public Assistance for help with housing, childcare, food stamps, or TANF.45 HELP-Link staff then work with those partner organizations to provide participants with comprehensive case management. Similarly, CareSource’s JobConnect life coaches work closely with participants throughout every step of the program, from initial screenings to post-employment check-ins, to ensure that members are receiving services that address their barriers to employment and then allow them to advance in new jobs.

Across initiatives, state resources may not be adequate to provide the full level of support required to address low-income Medicaid enrollees’ barriers to work. For example, while Montana operates HELP-Link with specifically allocated state funds, the state has acknowledged the insufficiency of those resources to meet demand for the program. As a result, the state has so far targeted resources to a subset of the HELP-Link-eligible population to make most efficient use of available funding, noting that other Montana Medicaid enrollees may face barriers that hinder their participation in the program. Under the 2019 legislation that extended HELP-Link, the state is exploring changes to the program to increase its cost-effectiveness and expand participation. In Louisiana and Maine, the governors have developed new programs or emphasized existing ones that can help address Medicaid enrollees’ barriers to work, but the states have not indicated whether additional staff or funding is available to support these initiatives. Finally, while CareSource is covering 90% of the cost of JobConnect operations, it is unclear whether most managed care plans have sufficient resources to do so, and how managed care plans can fund such initiatives more generally. Such questions about adequate resources pertain to both maintaining existing program operations and expanding the programs to more eligible participants who could benefit from them.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, it will be important to evaluate the effects of the small number of existing voluntary work support programs on enrollee participation and employment rates and to identify common elements of success and key challenges as well as costs needed to administer a successful program. Montana has published state data and reports46 on outcomes through SFY 2019, and there may be an opportunity to compare that experience with a work requirement (including any increase in work, as well as coverage losses due to noncompliance), if it is ultimately implemented in the state. The state’s legislation scheduled the Medicaid work requirement to take effect beginning January 1, 2020, contingent on CMS approval of the Section 1115 waiver that the state submitted in August 2019. However, the state announced in November 2019 that it would not be able to follow that schedule given that it is still awaiting federal approval of its waiver.47 In addition, although Louisiana had planned to release early results from the LDCC pilot program, which is scheduled to run through the end of December 2019, the state has yet to publish implementation documents or initial program findings. MCOs with work support programs like JobConnect can share best practices and collect data to build their evidence base, with a particular focus on Medicaid enrollee participation and outcomes. Evaluation of these and other work support initiatives can help other states, communities, and plans develop similar models.

Voluntary work support programs offer an opportunity to address enrollee employment needs, but funding presents a challenge. State efforts to invest in voluntary work support programs may be able to increase employment rates among Medicaid expansion enrollees without conditioning eligibility on employment. CMS indicated that it cannot make federal Medicaid matching funds available for such programs, so successful models must find other resources to address Medicaid enrollees’ barriers to work. MCOs can explore opportunities to use “value-added” services or other funding mechanisms to address enrollee social determinants of health. As Medicaid work requirements continue to face litigation, and research shows limited gains in employment from such requirements, voluntary programs that support work and can be implemented without waiver authority can provide another option for states interested in supporting work for enrollees who qualify through non-disability pathways. However, their success may be limited without an infusion of new resources.