State Efforts to Expand Medicaid Coverage & Access to Telehealth in Response to COVID-19

| Key Takeaways |

To increase health care accessibility and limit risk of exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic, all fifty states and DC are expanding telehealth access for Medicaid beneficiaries. This issue brief highlights recently released federal guidance to assist Medicaid programs in developing telehealth policies in response to the COVID-19, discusses trends in state Medicaid activity to expand coverage and access to telehealth, and highlights state and federal activity support provider infrastructure and patient access to telehealth.

|

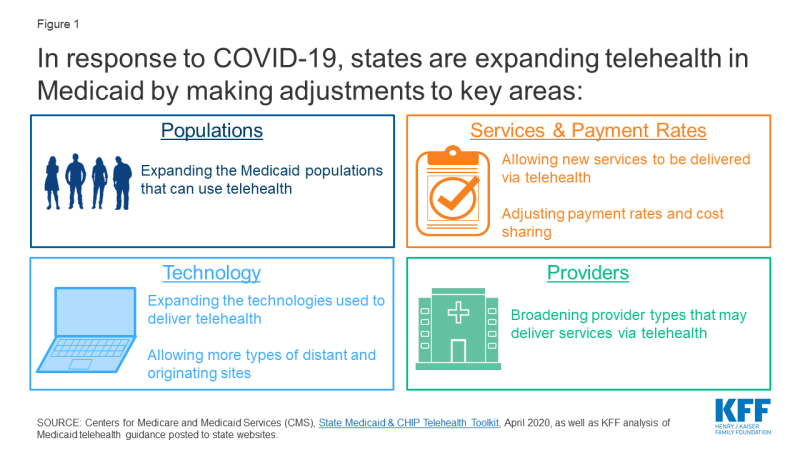

Figure 1: In response to COVID-19, states are expanding telehealth in Medicaid by making adjustments to key areas:

Introduction

Telehealth can help limit risk of coronavirus exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic, and is important both for those who are unable to physically go to the doctor and more broadly when in-person visits are inadvisable. Telehealth can enable remote screening for those with COVID-19 symptoms, while patients with other health concerns can use telehealth to avoid potential viral exposure at health care facilities.

There are few federal requirements, or restrictions, involving coverage of telehealth in the Medicaid program.1 The federal Medicaid statute does not define telehealth as a specific service and CMS, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, had issued little guidance on state use of telehealth. States have broad flexibility to determine whether to cover telehealth, which services to cover, geographic regions telehealth may be used, and how to reimburse providers for these services (including whether to require payment parity for services delivered via telehealth as compared to face-to-face services). If a state reimburses for services delivered via telehealth in the same way/amount that it pays for face-to-face visits, the state is not required to submit a separate state plan amendment (SPA) for coverage or reimbursement of these services.2 Telehealth coverage policies may differ between fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid and Medicaid managed care. Although there are few federal Medicaid requirements involving the coverage of telehealth, Medicaid programs must follow other applicable federal and state laws and regulations including those related to patient privacy (e.g., HIPAA), prescribing, provider licensing, and scope of practice.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telehealth in Medicaid was becoming more common, particularly to address barriers to care including insufficient provider supply (especially specialists), transportation barriers, rural access challenges,3 and stigma associated with receiving behavioral health care.4 All states had some form of Medicaid coverage for services delivered via telehealth, but reimbursement and regulation policies varied widely. As of February 2020, Medicaid programs in all fifty states and Washington, DC reimbursed some type of live video telehealth service delivery in FFS Medicaid programs; however, the scope of this coverage was inconsistent across states and many included restrictions on the type of services, providers, and originating sites. Most states prohibited or had no guidelines for audio-only telephone services. Fewer than half of states allowed the patient’s home to serve as the originating site, meaning that patients could access services via telehealth from their homes.5

This brief highlights recently released federal guidance to assist Medicaid programs in developing telehealth policies in response to the COVID-19, discusses trends in state Medicaid activity to expand coverage and access to telehealth, and highlights state and federal activity to support provider capacity to implement telehealth service delivery as well as strategies and activities to ensure patient access to these services. (Also see KFF’s Opportunity and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond.)

State Actions to Expand Medicaid Telehealth Coverage and Access

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has released a COVID-19 FAQ document (last updated May 5, 2020) which notes the broad flexibility states have to cover telehealth through Medicaid and addresses flexibilities for telehealth payment rates, reporting, and managed care organizations (MCOs), among others. To further guide states in establishing new telehealth policies to increase access during the pandemic, CMS released a State Medicaid & CHIP Telehealth Toolkit on April 23, 2020. The toolkit identifies key areas of telehealth for state consideration:

- Populations: Which Medicaid populations can receive services via telehealth? Do patients need to have an existing patient-provider relationship to receive services via telehealth?

- Services and Payment Rates: Which services can be delivered via telehealth and how will these services be reimbursed? Are services delivered via telehealth subject to cost sharing requirements?

- Providers: What types of providers can deliver services via telehealth and is any training required? Are any changes to licensing requirements or scopes of practice warranted?

- Technology: What telehealth modalities (e.g. videoconference, audio-only phone) can be used to deliver services and what privacy laws need to be considered? What kinds of sites can serve as distant sites (provider location) and originating sites (patient location)?

- Managed Care: Are managed care plans required to cover all services delivered via telehealth that are available in FFS Medicaid? Are cost sharing requirements different under managed care plans? Do managed care contracts need to be amended to extend the same flexibilities authorized under state plan, waiver (i.e., 1915(b) or 1915(c)), or demonstration (i.e., Section 1115)?6 Do managed care contracts need to be amended to reflect utilization of telehealth?

As referenced in the toolkit, states can broaden access to telehealth using Medicaid emergency authorities, which require CMS approval. As of June 15, 2020, 51 states (including DC) are using Section 1135 waivers to allow out-of-state providers with equivalent licensing in another state to provide care to Medicaid enrollees. Twelve states (including DC) are using Disaster-Relief SPAs to authorize telehealth payment variation and/or to include ancillary telehealth delivery costs. States are also using Section 1915 (c) Waiver Appendix K strategies to amend home and community-based services (HCBS) to broaden access to telehealth: 47 states (including DC) are permitting virtual eligibility assessments and service planning meetings and 44 states (including DC) are allowing electronic service delivery.

States have broad authority to take additional steps to expand coverage and access to services delivered via telehealth that may not require CMS approval, including modifications to Medicaid FFS policies and to MCO requirements. Most Medicaid telehealth policy changes made in response to COVID-19 will expire with the end of the public health emergency, although states may choose to make some changes permanent. As of June 15, 2020, 49 states (including DC) have issued specific guidance to expand coverage and access to telehealth in response to the pandemic. For example:7

- States are expanding the Medicaid populations that can utilize telehealth. At least 11 states are waiving the requirement that provider-patient relationships be established in-person prior to the use of telehealth.

- States are newly allowing certain services to be delivered via telehealth and are adjusting provider reimbursement rates and patient cost-sharing. At least 39 states (including DC) have established payment parity for at least some services delivered via telehealth as compared to face-to-face services. At least 20 states are waiving or lowering telehealth copayments (note that some states did not charge cost-sharing for any or all services prior to the pandemic). States are also making it easier to obtain patient consent for telehealth: for example, at least 4 states that previously required written consent are newly allowing verbal consent only.

- States are broadening the provider types that may provide services via telehealth, including adding new providers and waiving licensing requirements. At least 11 states are allowing federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and/or rural health clinics (RHCs) to provide services via telehealth. Given that Medicaid patients comprise a significant portion of these clinics’ patient populations, these rule changes could significantly impact the reach of telehealth under Medicaid.

- States are expanding the technologies allowed for telehealth service delivery and the originating sites at which patients can receive services via telehealth. At least 26 states (including DC) are allowing the patient’s home to serve as the originating site. States are also expanding the modalities by which services can be delivered via telehealth. For example, at least 38 states are allowing some or all services to be provided via audio-only telephone communications.

In addition to the steps noted above, states are also issuing guidance to broaden telehealth access for specific services, including:

Behavioral health: Many states have issued guidance for behavioral health providers and are expanding telehealth access to behavioral health services, such as diagnostic evaluations, psychotherapy and medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Some states are broadening the practitioner/provider types that may provide behavioral health services via telehealth. States may impose different requirements on different behavioral health services. At least 41 states are allowing telehealth delivery of behavioral health services.8 Examples include the following:

- Pennsylvania is newly allowing any practitioners who provide necessary behavioral health services to utilize telehealth. This change and other telehealth extensions in the state apply to behavioral health services delivered to Medicaid beneficiaries via FFS or through Behavioral Health MCOs.

- Unlike many states that exclude all or most residential treatment services from those available via telehealth, Maryland is allowing substance use disorder (SUD) residential treatment programs to provide Medicaid services via telehealth until the end of the COVID-19 emergency.

- Connecticut is requiring that enrollees be at Medicaid-enrolled originating sites to receive certain behavioral health services via telehealth (including psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and opioid treatment programs) but places no limitations on the originating site for telehealth delivery of individual therapy, family therapy, and psychotherapy with medication management.

Pediatric services: States are allowing the use of telehealth for Medicaid-funded well-child visits and services and are more likely to do so for children older than 24 months, in accordance with guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics. At least 13 states have issued guidance for telehealth well-child and EPSDT visits.9

- States such as Maine, North Carolina, and Rhode Island are allowing telehealth well-child visits delivered via FFS and/or through MCOs and require follow-up in-person visits as soon as possible. Kentucky requires the in-person follow-up visit to occur within 6 months of the end of the declared emergency.

- States may newly allow other pediatric services to be delivered via telehealth—for example, Colorado has added pediatric behavioral therapy services to its list of eligible services to be delivered via telehealth.

Reproductive and maternal health services: Expanded access to telehealth service delivery in most states includes family planning services. States with extended Medicaid eligibility programs for family planning services may allow telehealth for these enrollees as well. For example,

- North Carolina is allowing both traditional Medicaid beneficiaries and beneficiaries of its family planning Medicaid program to receive select family planning services via telehealth.

- North Carolina has also expanded Medicaid-covered telehealth service delivery to include perinatal care, maternal support services, and postpartum depression screening.

- Alaska is newly allowing direct entry midwives to provide some services using telehealth.

Services for beneficiaries with COVID-19: States are issuing guidance to ensure that Medicaid beneficiaries with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 can receive services via telehealth. Examples include:

- Louisiana and Nebraska have added reimbursement for telephonic evaluation and management services for Medicaid beneficiaries (including those covered by FFS and MCOs) actively experiencing symptoms of COVID-19.

- Massachusetts has added a billing code for COVID-19 remote patient monitoring (RPM) for Medicaid beneficiaries with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 who are isolated at home or in a community-based setting. RPM is the electronic transmission of patient health data from the originating site to a provider at a distant site for assessment. Separate guidance clarifies that all Medicaid health plans in Massachusetts (including MCOs) are required to cover the new COVID-19 RPM bundle of services.

Dentistry services: Many states are expanding teledentistry in Medicaid, but often require these services to be provided using video technology and exclude audio-only delivery.

- Maryland and Ohio are allowing dentists to utilize telehealth to provide limited problem-focused oral evaluations.

- Kentucky is allowing for screenings, assessments, and examinations to be provided via teledentistry.

Speech therapy, physical therapy, and occupational therapy: At least 32 states cover telehealth delivery of speech therapy, physical therapy, and occupational therapy services.10 For example:

- Missouri and Ohio have issued guidance on procedure codes for telehealth delivery of services that provide speech therapy, physical therapy, and occupational therapy. In both states, providers may use these codes to bill services provided to beneficiaries covered by FFS and MCOs.

Many state directives and guidance expanding telehealth in Medicaid apply to all delivery systems including managed care organizations (MCOs), although there is some variation. For example, Massachusetts requires that managed care entities provide all Medicaid services and provider flexibilities at the same level and rate as the state’s fee-for-service FFS program during the COVID-19 emergency. On the other hand, Florida acknowledges that its MCOs have broad flexibility to cover services delivered via telehealth and set their own requirements and rates, and the state’s telehealth policy applies only to its FFS delivery system. Florida is separately encouraging MCO plans to maximize the use of telehealth.

Activity to Support Provider Infrastructure and Patient Access to Telehealth in Medicaid

Both states and the federal government are taking action to support provider provision of telehealth broadly and Medicaid. Telehealth requires technology and internet access from both patients and providers that may not already be in place. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act appropriated $29 million annually for five years to the Telehealth Network Grant Program to fund telehealth technologies for nonprofit entities that provide direct services to rural and medically underserved areas. The Act also included $200 million for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that will fund the COVID-19 Telehealth Program, which provides financial support to nonprofit and public eligible health care providers for telecommunications services, information services, and devices necessary to provide critical connected care services. Although this program is not exclusive to Medicaid providers, the FCC has noted that funding decisions will take into account whether providers serve low-income patient populations and plan to target funding to high-risk and vulnerable patients. States can take additional action to facilitate provider use of telehealth. For example, providers in Washington can receive Zoom video conference licenses free of charge, with priority given to providers who serve a meaningful number of Medicaid clients.

States and the federal government are also increasing accessibility of telehealth for patients. Medicaid beneficiaries face particular barriers to accessing services via telehealth: in 2017, 26% of nonelderly, non-SSI, non-dual eligible Medicaid adults reported that they never use a computer and 25% reported that they do not use the internet. Further, adults in rural areas—which, as reported by the FCC, are significantly more likely to lack sufficient access to broadband internet—are also more likely to be covered by Medicaid than those in urban and other areas, with 24% of rural adults covered by Medicaid in 2015. To facilitate patient access to phone and internet services necessary for telehealth during the pandemic, the FCC has relaxed certain recertification, eligibility, and enrollment requirements for Lifeline, a federal program that provides subsidized phone and/or internet service to low-income households (enrollment in Medicaid, among other programs, makes one eligible for the program). States including Massachusetts and New York have issued resources to provide Medicaid beneficiaries with information about options for accessing technology required for telehealth. To further make telehealth more accessible to enrollees, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) has notified providers that they may reduce or waive cost-sharing obligations beneficiaries owe for services delivered via telehealth without being subject to OIG administrative sanctions. As of June 15, 2020, 18 states are broadly waiving cost sharing charges in their Medicaid programs and 20 have issued guidance to waive or lower telehealth copayments specifically (note that some states did not charge cost-sharing for any or all services prior to the pandemic).

Looking ahead

Prior to the pandemic, state coverage of telehealth in Medicaid varied widely. States took many factors into consideration including budget limitations, patient and provider acceptance, scope of practice laws, operational/technology challenges and costs for providers and patients, evidence around quality and effectiveness of services delivered via telehealth, concerns involving potential for fraud and abuse among others.11 Although state coverage of telehealth in Medicaid still varies widely, widespread changes to Medicaid telehealth policies undertaken during this public health emergency will provide additional information and evidence involving the use and effectiveness of telehealth. Although certain Medicaid telehealth policy changes may expire with the end of the public health emergency, states may consider making permanent some changes initiated in response to the COVID-19 crisis.