Policy Options to Sustain Medicare for the Future

Section 3: Delivery System Reform and Care for High-Need Beneficiaries

.

Delivery System Reform

Options Reviewed

This section discusses two policy options to promote delivery system reform and improve the functioning of the current delivery system, while laying the groundwork for more fundamental change:

» Accelerate implementation of payment reforms authorized under the Affordable Care Act

» Provide real-time information to improve clinical decision-making by physicians and other health professionals under current and reformed payment systems

Changing incentives to address growing quality and spending concerns—especially for patients with multiple chronic conditions and frailty—is an ongoing effort that has been gaining momentum in recent years. Many of the existing Medicare payment policies have been criticized for rewarding physicians and other providers for quantity rather than value and for lacking incentives to improve patient care by encouraging better coordination among providers (Hackbarth 2009). In recent years, Congress has taken several steps to foster delivery system reform by investing in health information technology, by creating a stronger infrastructure for comparative effectiveness research, and through numerous provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that aim to test new payment models. These efforts have the potential to change current incentives to promote greater collaboration among health professionals and institutional providers, provide greater support for primary care, discourage unnecessary and costly care, and reward providers for high-quality patient care.

The ACA includes numerous provisions focused on delivery system reform, including demonstrations that test models of care—such as medical homes, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), and the Independence at Home “house calls” for frail and disabled beneficiaries—and various forms of bundled payment episodes for different collaborations of providers, including hospitals and physicians, and hospitals and post-acute care facilities. The ACA also created the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and gave CMMI the authority to incorporate successful demonstrations into Medicare without obtaining new authority from Congress if the CMS Actuary certifies, based on formal evaluation, that the demonstration increases quality without raising Medicare spending or reduces spending without a diminution in quality. The ACA provides $10 billion over 10 years to support these efforts.

Since its establishment, CMMI has launched several new initiatives (Exhibit 3.1). For instance, CMS currently is implementing and assessing two models of ACOs. The Medicare Shared Savings Program is aimed at recruiting new provider groups to test the ACO model. In 2012, CMS announced that 153 organizations were participating in the shared savings program, serving over 2.4 million Medicare patients across the country (CMS 2012). The Pioneer ACO Model is designed for health care organizations and providers that already are experienced in coordinating care for patients across care settings. As of 2012, there were 32 ACOs participating in the Pioneer ACO Model. In addition, CMMI has launched programs to improve the availability of, and compensation for, primary care, approaches to improve patient safety, and efforts to reduce preventable readmissions, and efforts to help elderly and disabled persons remain at home (CMMI 2011; GAO 2012).

CMMI is getting ready to launch a “Bundled Payments for Care Improvement” initiative, that would link payments for multiple services patients receive during an episode of care. These efforts build on earlier demonstration projects conducted by CMS, including one testing bundled payments for acute care episodes (ACEs), launched in 2009. This project was designed to test the effect of bundling Part A and Part B payments for episodes of care to improve the coordination, quality, and efficiency of care for patients receiving hip and knee joint replacements and specified cardiac procedures (CMS 2009).

Policy Options

OPTION 3.1

Accelerate implementation of payment reforms authorized under the Affordable Care Act

Some experts have suggested that the current timetable for implementing delivery system reforms is too slow and encumbered by the voluntary nature of the programs. Given broad interest in moving forward to modify payments in a way to encourage value rather than volume, these experts have proposed moving more rapidly than is currently planned from demonstration to full implementation where there is early evidence of success and a plausible case for the effectiveness of the approach if it were widely adopted (Emanuel et al. 2012). For example, proponents of a more expedited approach have urged CMMI to expand the ACE demonstration to include more types of care and services (Cutler and Ghosh 2012). Proponents also urge CMMI to put implementation of shared savings models such as ACOs on a faster track.

Those advocating more rapid adoption of new payment methods also have suggested announcing a firm date by which providers will be expected to accept new payment models or specific limits on current payment rates to provide greater certainty for providers, along with added pressure to lead providers to participate in new organizational and payment arrangements. For example, a group of experts has suggested that within 10 years, Medicare and Medicaid should strive to base at least 75 percent of payments in every region on alternatives to fee-for-service payment (Emanuel et al. 2012).

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Advocates of accelerating delivery system reform argue that current fee-for-service payments encourage wasteful use of high-cost tests and procedures and that rapid change is needed to improve care outcomes, slow the growth in health care spending, and eliminate excess costs. According to this line of reasoning, until providers are certain that Medicare is moving inexorably away from current payment systems, progress will be too slow; if Medicare sends an unambiguous signal with a clear timetable, providers will have time to make changes as needed (Emanuel et al. 2012). Proponents of this option point to early results from two ACE demonstration sites that indicate that the joint hospital–physician collaboration for providing these services saves money by increasing bargaining power for equipment and supplies from vendors, as a result of the physicians agreeing to use a limited number of devices and supplies to increase their leverage over prices (MedPAC 2011). Some also point to positive results on shared savings. For example, in Massachusetts, 11 physicians groups with a total of 1,600 primary care physicians and 3,200 specialists participated in a five-year Massachusetts Blue Cross Blue Shield project testing the use of global payments to control spending and improve quality, which achieved two-year savings of 2.8 percent in medical costs (although once other payments made to the groups for quality, other bonuses, and technical support were considered, the approach actually cost more in total) (Song et al. 2012).

Others caution against moving too quickly to implement demonstrations on a large scale, however, pointing to the uneven record of past Medicare demonstration projects (CBO 2012). There is a concern that rapid adoption of shared-risk arrangements and other reforms may not achieve the desired results. These experts urge policymakers to take more time to test various models before applying them more broadly, stating that a realistic window to make major organizational change for typical provider organizations is five to seven years (Burns and Pauly 2012). They argue that “first movers” or “early adopters” may not be representative of all providers and that, even if a model is successful with such early adopters, it may not achieve the same results when applied more broadly. More concretely, some experts caution that demonstrated per case savings in the ACE demo could be offset by growth in the number of procedures performed, as suggested by early data from the demonstration sites (MedPAC 2011). Proponents of a more cautious approach recommend waiting for formal, comprehensive results and testing over a longer period of time before drawing conclusions from promising, but partial, findings.

OPTION 3.2

Provide real-time information to improve clinical decision-making by physicians and other health professionals under current and reformed payment systems

Not all providers easily fit into new organizational paradigms, such as ACOs, that may involve some level of shared risk. For example, in some areas, providers may lack the critical mass needed to support financial risk-taking, and some providers may be so specialized or serve such a unique population that paying them using a form of volume-based payment would continue to be the simplest and most reasonable approach. While Medicare tests and implements new payment models, this option could complement existing and evolving payment and delivery systems to improve quality and lower costs.

Following the lead of many commercial insurers, one option would be for Medicare to contract with vendors that specialize in data mining to allow “real-time” analysis of each beneficiary’s health data from claims to identify gaps in care, such as failure to receive recommended preventive services, prescription drug errors, medication incompatibilities, and other apparent deviations from quality care. A number of entities have developed proprietary clinical rules relying on computer algorithms to assess disease prevalence, medical care and prescription drug-use patterns, and compliance with current evidence-based clinical practice guidelines within a health plan population. Using analytic results, the vendors identify specific opportunities to suggest interventions to clinicians and patients that correct inefficient or potentially harmful care.

In one example, decision support software collects information about patients from billing records, laboratory results, and pharmacies to assemble a virtual electronic medical record (Javitt et al. 2008). It then passes this information through a set of decision rules drawn from the medical literature. When the software uncovers a potential issue of concern in the patient’s care, it produces a message to the patient’s physician identifying the issue uncovered, a suggested course of corrective action, and citation to the relevant medical literature. Physicians remain in control of the actual clinical decision-making.

As currently used by commercial plans, this approach is designed to support, rather than regulate, clinical practice by ad-dressing the complexity of care provided by the many providers who do not share a common health record. Varied approaches are used to inform clinicians and patients about actionable clinical information that suggests patient safety issues and gaps in care, as well as to provide patients with recommendations to enhance self-management of chronic conditions. For example, one vendor notifies physicians by phone when there is an urgent issue regarding care for a patient, and by fax, email, or regular mail for less urgent issues. CMS would assume the role of the health plan for traditional Medicare, presumably relying on vendors for the analytics and interventions. Rather than move to full-scale implementation of this option, a program to pilot test this option could also be adopted.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. There would be administrative costs for performing the analytics and acting on the findings.

Discussion

This option could give providers more information, on a timely basis, to help improve patient care, following the lead of some private insurers who increasingly rely on data analytics to support physicians and other clinicians. Savings could be achieved as a result; one peer-reviewed controlled study found that the approach lowered average charges by 6 percent relative to the control group (Javitt et al. 2008).

CMS would face the challenge of developing an administrative infrastructure for obtaining the specialized services offered, and would need to address whether to work through current Medicare administrative contractors or contract directly with vendors on a national or local/regional basis. Another challenge is whether this level of clinical management from the claims payer is viewed as part of the mission of traditional Medicare; some physicians and patients might view this ostensibly supportive role as intrusive.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Lawton Burns and Mark Pauly. 2012. “Accountable Care Organizations May Have Difficulty Avoiding the Failures of Integrated Delivery Networks of the 1990s.” Health Affairs, November 2012.

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). 2011. One Year of Innovation: Taking Action to Improve Care and Reduce Costs, 2011.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2012. Shared Savings Organization Fact Sheet. July 9, 2012.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2009. Acute Care Event (ACE) Demonstration Project Fact Sheet, 2009.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012. Lessons from Medicare’s Demonstration Projects on Disease Management, Care Coordination, and Value-Based Payment, January 2012.

David Cutler and Kaushik Ghosh. 2012. “The Potential for Cost Savings Through Bundled Episodes,” New England Journal of Medicine, March 22, 2012.

Ezekiel Emanuel et al. 2012. “A Systemic Approach to Containing Health Care Spending,” New England Journal of Medicine, September 6, 2012.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2012. CMS Innovation Center: Early Implementation Efforts Suggest Need for Additional Actions to Help Ensure Coordination with Other CMS Offices, November 15, 2012.

Glenn Hackbarth, Chairman, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2009. Testimony before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, March 10, 2009.

Jonathan Javitt et al. 2008. “Information Technology and Medical Missteps: Evidence From a Randomized Trial,” Journal of Health Economics, May 2008.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2003. Report To the Congress: Variation and Innovation in Medicare, June 2003.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2011. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. June 2011.

Zirui Song et al. 2012. “The ‘Alternative Quality Contract,’ Based On A Global Budget, Lowered Medical Spending And Improved Quality,” Health Affairs, August 2012.

High-Need Beneficiaries

Options Reviewed

This section discusses three sets of options to improve care and reduce costs for high-need Medicare beneficiaries:

» Implement Medicare models of care for high-need beneficiaries

» Implement State-based models for beneficiaries covered by Medicare and Medicaid

» Improve coverage and provision of palliative care

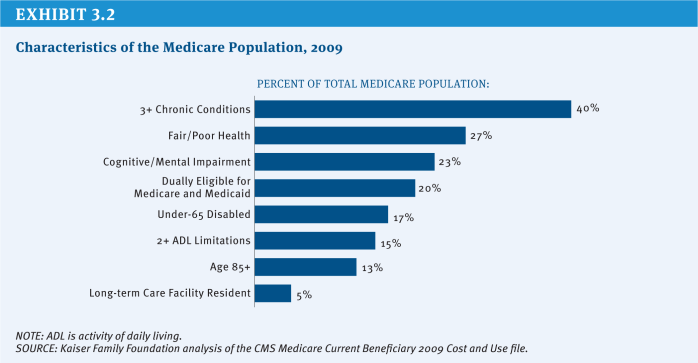

The search for strategies to improve care and reduce excess spending for people with high health care needs continues to be a high priority for Medicare policymakers, as it is for other health care payers and providers. Many people with Medicare live with multiple chronic conditions, fair or poor health status, and cognitive impairments (Exhibit 3.2). Definitions of high-need populations vary but typically refer to people with multiple chronic conditions, often with functional and/or cognitive impairments, who are at risk of being high users of medical services. Because of their complex needs and compromised health, they often are in greater need of care coordination and at greater risk of potentially preventable and costly hospitalizations, readmissions, and emergency room visits, among other services.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes several provisions designed to test ways to improve care and reduce care costs for Medicare beneficiaries, especially those with high needs. For example, the newly created Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is authorized to test and evaluate whether different payment models can reduce spending while preserving or enhancing the quality of patient care. These include such models as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments for episodes of care. The ACA also created a Federal Coordinated Health Care Office, within CMS, to focus on those beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. This office is working with CMMI to test mechanisms for integrating the financing and care for dually eligible beneficiaries, many of whom have significant needs, including demonstrations to test integrated capitated and managed fee-for-service models of care for dual eligibles (the Financial Alignment Model) and models for reducing hospital admissions among nursing home residents (Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations of Nursing Facility Residents) (CMMI 2012). CMS also is modifying current payment policy to compensate providers for services that are focused on preventing hospital readmissions in an effort to reduce unnecessary care and costs for high-need populations.

This section discusses options to build on current efforts that test approaches to contain costs and improve care for high-need beneficiaries. In addition to the options described here, other parts of this report discuss options that would contribute to the goal of improving care management for high-need beneficiaries (see Section Three, Delivery System Reform and Section Five, Governance and Management, Option 5.13).

Policy Options

Implement Medicare Models of Care for High-Need Beneficiaries

Beneficiaries with high needs tend to be heavy users of Medicare-covered services and account for a disproportionate share of Medicare spending. People with Medicare can have significant needs for many reasons, including declining health status due to aging, sudden onset of a severe chronic condition, or the development of a disabling physical or mental condition. Although, in general, beneficiaries with such needs would be expected to require and use more services, there now is compelling evidence that some of this care reflects preventable use of hospital and related services. Between 15 percent and 20 percent of all Medicare inpatient hospital admissions, and between 25 percent and 30 percent of all readmissions within 30 days, are considered potentially preventable with timely and appropriate discharge planning and follow-up care (MedPAC 2008; Stranges and Stocks 2010).

OPTION 3.3

Scale up and test care coordination and care management approaches that have demonstrated success in improving care and reducing costs for well-defined categories of high-need beneficiaries in traditional Medicare

Under this option, CMMI would test whether specific interventions and protocols that already have proved effective in reducing costs on a relatively small scale (through a demonstration project) can be replicated and scaled up and succeed in reducing preventable hospitalizations and other services for high-need beneficiaries. CMMI would invite providers and plans to implement well-defined interventions targeted at specific subgroups of the high-need Medicare population, and would conduct ongoing analysis to identify the attributes that distinguish the most successful programs from others, with the ultimate goal of implementing successful models nationwide. With this option, CMMI would use its authority under the ACA to test the replication of proven care models that reduce costs for specific groups of beneficiaries, and ultimately use this information to broadly implement better management of high-need beneficiaries under traditional Medicare.

Although many care coordination demonstrations have not succeeded in achieving net savings and reducing utilization of unnecessary services across all demonstration sites, some of the care coordination entities participating in these demonstrations have reduced hospitalizations and, in some cases, generated savings, for specific patient subgroups. Positive results stand out for two specific populations: (1) beneficiaries living in the community whose chronic conditions and acute care needs put them at high risk for hospitalization (Brown and Mann 2011) and (2) beneficiaries living in long-term care facilities (Brown and Mann 2011; Ouslander and Berenson 2011), a subset of the Medicare population that accounts for a disproportionate share of Medicare spending due to relatively high rates of hospitalizations (Jacobson, Neuman, and Damico 2010).

There is some evidence of success with care management protocols focused on beneficiaries at high risk of hospitalization when they are targeted and include specific protocols for the intervention, such as the frequency of contact between care managers, patients, and physicians. For example, two of the 15 Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstrations achieved net savings of more than $3,000 per person per year for beneficiaries with congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or coronary artery disease (CAD) who experienced a hospitalization in the year prior to enrollment.1 The Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) care coordination model reduced net costs by about $1,500 per person per year through a 40 percent reduction in hospitalizations in the third year after the intervention started, but only for a subset of the study patients who were deemed to be at high risk of hospitalization (Counsell et al. 2009). One of the six programs participating in CMS’s Case Management for High-Cost Beneficiaries Demonstration achieved savings by reducing hospital and emergency department use, with expenditures (including fees) 12 percent lower than the comparison group during the first three years (McCall, Cromwell, and Urato 2010). For beneficiaries living in nursing homes, the Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transitions (INTERACT 2) model demonstrated a 17 percent reduction in hospitalizations over a six-month period, with estimated savings of about $1,250 per nursing home resident (Ouslander and Berenson 2011).

This option would test whether these protocols that have demonstrated success on a relatively small scale can be appropriately targeted and replicated by a broader set of providers to achieve the quality improvements and spending reductions observed in the small-scale programs. The fact that the successful programs included very different types of organizations in different settings suggests that broader dissemination could be successful.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Achieving savings and quality improvement from better care management relies on a combination of specific techniques and their application to beneficiaries who, without them, would probably receive expensive care that could have been avoided. Without effective targeting, the costs of care coordination interventions often exceed the savings from reduced hospitalizations. While some demonstration sites have been able to reduce costs, others have not (Brown and Mann 2011). Some programs were able to reduce hospitalizations, but the savings did not offset the cost of the interventions.

While this option is based on strong evidence, it is not clear whether these models will be effective or achieve savings when scaled up and applied more broadly, if targeting falls short or critical factors of the earlier models’ successes have not been replicated. Another potential concern with this approach is that, once implemented, the models could be difficult to terminate even if they did not achieve savings; regulations that call for termination of programs that did not achieve objectives in a pre-specified timeframe could help to minimize the risk of increased spending.

OPTION 3.4

Launch new Medicare pilot programs to test promising care management protocols for beneficiaries living in the community with physical or mental impairments and long-term care needs

Under this option, CMMI would test models of care for which there is some reasonable prospect of potential savings for this population through improved care management, based on programs conducted on a smaller scale or programs that were not targeted to this population. In contrast to Option 3.3, where fairly strong evidence already has been developed and much is known about the features that successful programs need to exhibit in order to improve care for well-defined categories of people with Medicare, this option is designed to develop, through pilot programs, evidence of comparable rigor and reliability for promising interventions for beneficiaries living in the community with physical or mental impairments and long-term care needs. If some of these pilots are successful, they could then be tested through larger demonstrations to assess their potential for wider dissemination (as in Option 3.3).

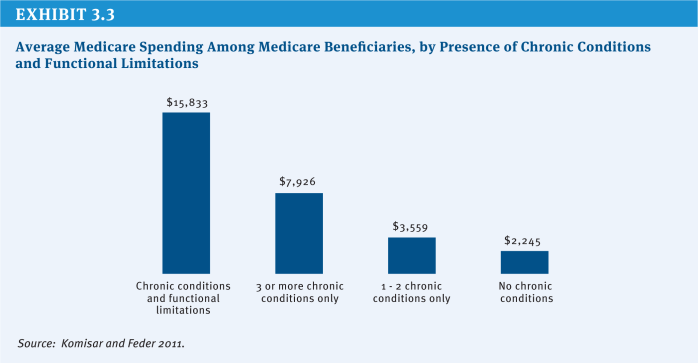

As an example, CMMI could develop Medicare pilots for beneficiaries who are dependent on long-term services and supports (LTSS) and require significant amounts of medical care—approximately 15 percent of Medicare beneficiaries (Komisar and Feder 2011). Beneficiaries with chronic conditions, broadly defined, have been the focus of several recent efforts to improve care and reduce Medicare’s costs; thus far, the evidence based on evaluations of programs and demonstrations suggests that finer targeting is needed to reach beneficiaries who are at greater risk of hospitalizations. Beneficiaries with chronic conditions coupled with functional impairments, who have disproportionately high Medicare expenditures—a subgroup of whom are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid—represent one appropriate target group (Lewin Group 2010) (Exhibit 3.3). Such beneficiaries could be the focus of new pilots that would test whether care management directed at their full range of care needs could avert unnecessary hospitalizations and use of other expensive services—such as skilled nursing facilities and home health care—and reduce Medicare spending.

Another subset of the Medicare population with relatively high rates of hospitalizations and relatively high costs are beneficiaries with both mental disorders and other chronic conditions. The co-occurrence of mental disorders and other chronic medical conditions serves to complicate the treatment of both sets of illnesses and substantially raises the costs of caring for the affected individual (Druss and Walker 2011). Depression and anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorders that accompany such chronic conditions as diabetes, CHF, asthma, and COPD. There is some evidence that a primary care intervention, known as collaborative care, for this population can achieve savings, based on a program that has been extensively tested in the context of over 40 clinical trials and demonstration programs and was also tested on a population of older adults in the IMPACT study; the latter showed cost savings over a three-year period of about 10 percent (Unutzer et al. 2008). Key elements of that intervention were: training of primary care physicians in evidence-based depression and anxiety treatment, a well-trained and supervised care manager, longitudinal tracking of patient progress, and specialty psychiatric back-up. Another application of the model to people with diabetes and depression showed savings of 14 percent of total costs over a two-year period (Katon et al. 2008). The studies suggest that targeted application of the collaborative care approach can yield savings when applied to older adults with multiple medical and mental health conditions. This approach could be imbedded in a Medicare demonstration of case management, which would require waiving payment rules regarding more than one claim from a single provider organization in a day.

In addition, Medicare could pursue care management demonstrations targeted to beneficiaries with severe and persistent mental disorders who are entitled to Medicare because they receive Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments. Roughly 40 percent of Medicare beneficiaries under the age of 65 suffer from a major mental illness, approximately 36 percent of whom live with one or more chronic medical conditions, in addition to their mental disorder. This group of beneficiaries incurs total annual costs of $25,000 to $35,000.2 Care management of this population involves greater complexity and a more extensive set of services than is the case for older adults served by the collaborative care model. Successful models of care coordination must manage mental health, substance use disorder services, medical care, and long-term services and supports, which typically involves a team approach led by medical personnel (usually a physician and a nurse) with care managers, peer counselors, and community health workers.

Washington State recently tested this approach on a relatively small scale and, in the initial years, experienced reduced inpatient use and improved health but few costs savings; however, subsequently they experienced annual savings of about 13 percent (Mancuso et al. 2010; Paharia 2012). The state recently has moved to implement this type of approach on a larger scale. Additional demonstrations targeted to Medicare beneficiaries with severe and persistent mental disorders could help to identify interventions that are most likely to succeed in reducing preventable inpatient care and achieving savings.

The aforementioned Medicare pilots could be applied to all Medicare beneficiaries who qualify, whether or not they are also eligible for Medicaid (dual eligibles), and could test the effectiveness of the intervention for both dual eligibles and other beneficiaries. CMMI also could continue to test and refine capitated managed care approaches that focus on coordinating and managing care specifically for dual eligibles who need long-term services and supports. Some of these limited programs or pilots have demonstrated considerable promise for reducing hospitalizations and nursing home admissions, and, in some instances, costs. For example, the Commonwealth Care Alliance (CCA) in Massachusetts operates two programs that receive capitated payments under Medicare and Medicaid: (1) Senior Care Options for dually eligible seniors living in the community, and (2) the Disability Care Program, with some evidence of success in reducing hospitalization rates, nursing home admissions among seniors, and costs (Brown and Mann 2012). In addition, the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE)—for beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid who require a nursing home level of care—has been successful in reducing hospitalizations, but has not achieved net Medicare savings for seniors with significant long-term care needs due to relatively high capitation payments (Foster et al. 2007; Beauchamp et al. 2008). Pilots that build on the strengths and avoid the pitfalls of small capitated programs may generate the outlines of a successful policy for reducing costs and improving quality for these high-need, high-cost populations. For both the CCA programs and PACE, the challenge is to set capitated payment rates low enough to generate savings relative to traditional Medicare, but high enough for the programs to provide the personalized care coordination services that have enabled them to reduce hospitalizations and be financially viable.

This option would assess whether care management models that show some promise can succeed in improving quality and lowering costs for well-defined subgroups of beneficiaries.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Supporters of this approach observe that specifically targeting high-need subsets of the Medicare population (such as those with functional impairments or mental health needs) would improve and expand the likely success of existing Medicare care management initiatives and fill a gap in Medicare’s demonstration portfolio. This approach also would engage the Medicare program directly in efforts to support more appropriate use of Medicare-financed hospital and post-acute services for these high-cost users. By focusing this initiative on Medicare beneficiaries with specific disabilities and conditions, rather than on dual-eligible status, this approach may be more likely to achieve success. In addition, this approach could create a pathway for improving care for all high-need Medicare beneficiaries, not just for those who are dual eligibles. Proponents argue that testing small pilots prior to testing larger demonstrations may help to avoid large-scale adoption of untested and unevaluated innovations that could risk entrenchment of policies that might not improve care or reduce costs.

Others express concern that this approach—developing policy interventions through iterative steps involving pilots, refined pilots, scaled-up pilots, and careful evaluations—would take too much time and that more aggressive action is needed to address well-documented problems that exist in the current system.

OPTION 3.5

Pay PACE plans like Medicare Advantage plans

both Medicare and Medicaid. Participants must be 55 or older and certified by the state as being eligible for a nursing home level of care. PACE has evolved, first through demonstration waivers and later through statute. The program aims to keep beneficiaries living in the community and provides a comprehensive set of services including: primary, acute, and long-term care; behavioral health services; prescription drugs; and end-of-life care planning. The program includes a range of supportive services, with a key feature being adult-day care. Although the program is available in 29 states and includes 84 plans, it has remained relatively small and served about 21,000 high-needs beneficiaries nationwide in 2012 (MedPAC 2012b). Evaluations of the PACE program generally have found that the program has improved the quality of life and care for enrollees, but due to the relatively high capitated payments, the program does not reduce Medicare spending (Foster et al. 2007; Beauchamp et al. 2008).

PACE plans are paid capitated payments from both Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare payments to PACE plans differ in several ways from payments to Medicare Advantage plans, and collectively result in higher payments to PACE plans than to Medicare Advantage plans in the same market. First, payments to PACE plans are based on the higher benchmarks (i.e., the maximum amount Medicare will pay plans) that were in place for Medicare Advantage plans prior to enactment of the ACA. The ACA did not lower the benchmarks for PACE plans, but did lower the benchmarks for Medicare Advantage plans. Second, PACE plans do not submit bids, unlike Medicare Advantage plans, and instead payments are set equal to the benchmark. This results in higher payments to PACE plans because most Medicare Advantage plans submit bids that are lower than the benchmark. Third, payments to PACE plans are risk adjusted using the Medicare Advantage risk adjustment methodology but with an additional payment for frail beneficiaries in the PACE program, resulting in higher payments to PACE plans. Fourth, PACE plans are not eligible for the quality bonus payments available to Medicare Advantage plans under the ACA.

In conjunction with improvements in the Medicare Advantage risk adjustment methodology (see Section Two, Medicare Advantage), including an evaluation of whether the improvements eliminate or reduce the need for a frailty adjuster for PACE plans, this option would pay PACE plans using the current-law benchmarks for Medicare Advantage plans and allow PACE plans to qualify for quality-based bonus payments. A similar option has been recommended by MedPAC (MedPAC 2012a).

Budget effects

MedPAC estimates that these PACE changes would reduce spending by less than $1 billion over five years, if implemented no later than 2015.

Discussion

These changes would better align PACE payments with traditional Medicare spending levels and with the measurable risk of the patient population. They would also promote equity among capitated programs that coordinate care for high-need beneficiaries. These changes would yield budget savings and provide an incentive for the plans to meet quality and patient experience thresholds to qualify for the bonus payments, just like Medicare Advantage plans.

However, there is some concern that the risk adjusters, even with improvements, would not adequately account for the higher costs of meeting the special needs of this population. Others worry that bringing the payment levels down to the Medicare Advantage benchmarks, while saving money in the short-term, may slow the development of the PACE model, which remains a small component of a system for frail beneficiaries, especially if the risk adjustment and payment models do not fully accommodate the costs of the program’s participants. Finally, the quality metrics used for Medicare Advantage plans may not be appropriate for PACE plans, and some argue that it may be misguided to provide incentive payments to PACE plans based on these metrics.

Implement State-Based Models for Beneficiaries Covered By Medicare and Medicaid

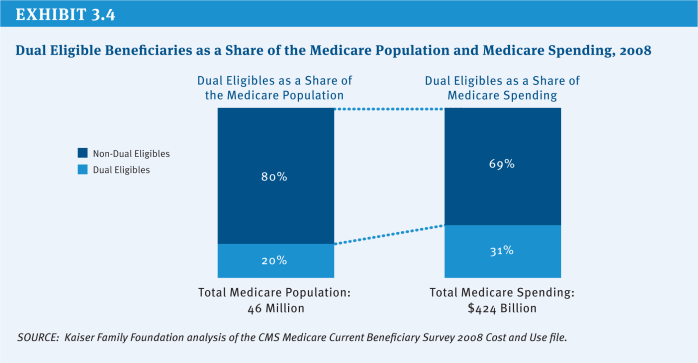

Nine million low-income elderly and disabled people—roughly 20 percent of the total Medicare population—are covered under both the Medicare and Medicaid programs (Exhibit 3.4). Compared with people with Medicare who are not covered by both programs, dual eligibles are much more likely to have extensive needs for long-term services and supports. Dual eligible beneficiaries encompass some of the sickest, frailest, and most costly beneficiaries in Medicare, although not all dual eligibles are high-need. In 2008, only one in four dual eligibles had an inpatient stay, and 16 percent had relatively low Medicare spending (below $2,500) (Kaiser Family Foundation 2012). Up to 38 percent of duals have neither multiple chronic conditions nor long-term care needs (Brown and Mann 2012).

Medicare is the primary source of health insurance coverage for the dual eligible population. Medicaid supplements Medicare, paying for services not covered by Medicare, such as dental care and long-term services and supports, and helping to cover Medicare’s premiums and cost-sharing requirements. Medicare beneficiaries who also are covered by Medicaid face the challenge of navigating two health care programs that typically do not work well together due to different benefits, billing systems, enrollment, eligibility, and appeals procedures, and often different provider networks. The lack of coordination between the two programs puts beneficiaries at risk of poorly coordinated care and unnecessary emergency room visits and hospitalizations, leading to poorer care and higher costs for both Medicare and Medicaid.

States may have minimal incentive to contribute to the coordination of care for dual eligible beneficiaries because most of the savings that would result from reductions in hospitalizations would accrue to Medicare. As a result, there is growing interest in approaches to encourage greater coordination across the two programs. Beginning in 2013, special needs plans for dual eligibles (D-SNPs) are required to have contracts with the states in which they operate to improve the coordination of Medicare and Medicaid benefits for dual eligibles; it is at the state’s discretion as to whether to issue contracts to D-SNPs. This requirement for D-SNPs may help to improve the coordination of benefits, although it does not provide states with a direct financial incentive to contribute to the coordination effort.

The CMS Federal Coordinated Health Care Office, in conjunction with CMMI, is working with states to develop programs to improve the coordination of care for dual eligibles and reduce spending under Medicare and Medicaid. The Financial Alignment Model aims to integrate Medicare and Medicaid financing and services for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, with savings from reduced hospitalizations and other services shared between the Federal government and the states. In 2011, 15 states received planning grants to develop proposals to integrate the financing and delivery of care for dual eligible beneficiaries. As of December 2012, more than 20 states had proposals pending with CMS to participate in the demonstration, and three states (Massachusetts, Washington, and Ohio) have signed an agreement with CMS and are expected to launch demonstrations in 2013. The demonstrations will test both capitated models (involving three-way contracts among CMS, states, and plans) and models that involve a managed fee-for service approach. The demonstrations are expected to include up to two million beneficiaries nationwide.

OPTION 3.6

Require beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid to enroll in comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans

This option would require beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid to enroll in comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans to receive their Medicare- and Medicaid-covered benefits. Medicaid would provide capitated payments to managed care companies, and Medicare would reimburse Medicaid for its share of the costs. The option was recommended by the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (Simpson-Bowles commission) as part of a plan to reduce the deficit (National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform 2010). As noted above, a demonstration is underway in some states to test the managed care option. In contrast to this option, the demonstration does not mandate that dual eligible beneficiaries enroll in managed care plans (some have passive enrollment with an opt-out) nor specify that all dual eligibles enroll in Medicaid (rather than Medicare) managed care plans. Additionally, not all states are participating in the demonstration, and some states are testing a managed fee-for-service approach rather than a capitated managed care approach that would be used in this option.

Budget effects

The Simpson-Bowles commission estimated that this option would save $1 billion in 2015 and $12 billion from 2015 to 2020. Since the commission made its recommendations, some states have planned to undertake demonstrations to improve the coordination of care for dual eligibles; the savings from this option may be smaller if implemented in conjunction with these state demonstrations.

Discussion

Proponents argue that this option would improve the quality of care for dual eligibles by providing financial incentives for states to coordinate their health and long-term care. The option, they argue, would reduce Federal and state spending by eliminating current incentives that result in duplicative and unnecessary services. Both Medicare and Medicaid could achieve savings by setting payments to managed care plans at a level that would be lower than current projected baseline spending (Lewin Group 2004). In addition, proponents note that Medicaid managed care plans have experience in managing low-income populations, and are well-positioned to improve the coordination and quality of care for dual eligibles, building on their existing provider networks (Meyer 2011).

Critics of this option argue that dual eligible beneficiaries should be entitled to the same plans and providers as all other Medicare beneficiaries, and should not be required to join Medicaid managed care plans as a condition of receiving their Medicare benefits. They also argue that the approach ignores the heterogeneity of the dual eligible population and fails to account for different health care needs of these beneficiaries. Opponents worry that the health plans could achieve savings not only by directly limiting access to care but also by paying providers at or near Medicaid rates rather than higher Medicare rates, potentially limiting access. Finally, some caution against passively enrolling beneficiaries into plans, and instead argue that dual eligibles should be required to actively make a choice as to whether to enroll in a managed care plan, in order to promote self-determination and the exercise of real options (Frank 2013).

Improve Coverage and Provision of Palliative Care

For 30 years, the Medicare hospice benefit to provide supportive end-of-life care has been a core part of Medicare. Currently, nearly half of beneficiary decedents use hospice before death. Concerns about possibly inappropriate use of hospice benefits for beneficiaries with declining health status who are not imminently likely to die, suggest the need for reconsideration of the purpose of hospice and whether access to palliative care for patients—whether or not they have a dire short term prognosis—is desirable.

Palliative care is an approach to providing care that addresses patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life, provides timely professional expertise for the seriously ill, and focuses on pain relief while offering the potential to moderate high spending near the end of life, enhance quality, and improve patient and family well-being. Interdisciplinary palliative care teams, comprised of physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and others, provide the following services: assessing and treating all symptoms, including pain; establishing a plan of care that matches treatment goals to those of well-informed patients and families; mobilizing practical aid for patients and caregivers; identifying community resources to ensure a safe and secure living environment; responding to concerns and crises at all times; and promoting collaboration across a range of settings, such as hospital, home, and nursing home.

Under current law, Medicare only offers a palliative care benefit as part of the hospice benefit for people with terminal illnesses in their last six months of life. There is no payment for the professional services associated with palliative care. Many hospitals provide palliative care as part of a package of services under the diagnosis-related group payment approach. The idea of expanding palliative care coverage under Medicare has gained attention as clinicians and policymakers search for ways to improve the experiences of patients with serious illnesses and limitations. Interest also is motivated by concerns about the use of hospice benefits for beneficiaries with declining health status, who are not imminently likely to die. There is also some evidence that palliative care might result in lower Medicare spending (Meier 2012).

Palliative care is not generally or necessarily provided as an alternative to curative care but can be provided concurrently. Some patients receiving palliative care have terminal prognoses, whereas others can live many years with their disabilities. Palliative care practitioners often attempt to mobilize long-term services and supports but are not financially responsible for doing so. In the U.S. (but not within the context of Medicare specifically), palliative care is provided both within and outside of hospice programs, the latter offered independent of the patient’s prognosis and concurrent with life-prolonging and curative therapies for persons living with serious, life-threatening conditions.

The absence of generally available palliative care could be contributing to the growth of possibly inappropriate use of hospice beyond its intended use, as costs for hospice in Medicare increased over the past decade from $3 billion to $13 billion (MedPAC 2012b).

OPTION 3.7

Incorporate the capacity to provide high-quality palliative care into Medicare’s hospital conditions of participation requirements, and develop and implement quality measures to assess the performance of palliative care for Medicare beneficiaries

As of 2009, 63 percent of community hospitals with at least 50 beds and 85 percent of hospitals with more than 300 beds reported having a palliative care program, affecting roughly 2 percent of discharges (Center to Advance Palliative Care 2011). Hospital-based palliative care programs have been shown in a series of studies to improve quality and patient well-being, while reducing costs of care for this population (Meier 2012).

There has been little emphasis on palliative care in performance measurement assessments, such as the value-based purchasing program for hospitals, quality measures for nursing homes, or quality indicators for Medicare Advantage plans.

This option would require hospitals to adopt palliative care programs as a Medicare condition of participation. In addition, it would direct the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to incorporate measures of core competency in palliative care in assessing and publishing quality indicators for providers and plans. Currently, Medicare conditions of participation do not include standards for palliative care. Moreover, to the extent value-based purchasing moves from process measures (e.g., palliative care team present) to disease-specific outcomes (e.g., mortality), the measures would need to be adjusted to distinguish preventable deaths from expected deaths so that hospitals do not face perverse incentives to forgo adoption of palliative care programs that might increase their reported mortality rates.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Hospital-based palliative care programs are diffusing rapidly, but more than one-third of community hospitals with at least 50 beds do not have these programs (Meier 2011). This option encourages the continued development and diffusion of quality palliative care. It addresses an often overlooked aspect of care and provides a corrective to the current bias toward prevention and cure, which may not be consistent with a patient’s best interests or wishes. Conditions of participation and relevant performance measures for palliative care would create incentives for plans and providers to develop quality palliative care programs, and potentially give patients a new tool for assessing providers and plans in their area.

However, there could be some concerns about this option because of its potential to increase the regulatory burden on providers and plans. Some might view these requirements as unnecessary given the fairly rapid spread of palliative care even in the absence of these initiatives.

OPTION 3.8

Launch a large-scale pilot to test palliative care as a Medicare benefit

This option would create a demonstration project to test alternative ways of paying for palliative care to beneficiaries outside of a hospital episode, as a possible precursor to developing a palliative care benefit under Medicare. The demonstration would test payments and delivery system options and assess whether access to palliative care improves the quality of life for patients, reduces pain, helps patients achieve their treatment goals, minimizes inappropriate use of hospice services, and reduces Medicare spending. Unlike Medicare’s current hospice benefit, this option would not require that a physician certify that a patient is likely to die within six months. In this way, beneficial palliative care for patients in need could be introduced at any point in patients’ declining health resulting from their underlying severe chronic illnesses, regardless of their prognosis. The demonstration also would test whether a palliative care benefit would reduce the portion of hospice payments associated with ongoing palliative care rather than the more intensive care provided in the last days of life.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. There is limited data on the spending effects of a broad palliative care benefit co-existing with ongoing curative therapy.

Discussion

When palliative care programs function well, patients are able to stay in their homes as a consequence of better family support and care coordination, rather than being hospitalized. In addition, palliative care produces more appropriate home care and hospice referrals; patients experience fewer days in intensive care units; and imaging, laboratory, specialty consultations, and procedures are avoided. Also, there is clearer guidance for all health professionals who may treat patients about patient preferences regarding resuscitation and other aggressive attempts at patient “rescue.”

Some studies demonstrate spending reductions as a result of care plans that reflect the informed wishes of patients and families, leading to a reduction of emergency room visits and readmissions, with more appropriate and timely referral to community hospice for those patients who have terminal conditions and to other programs that can provide supports for all patients (Meier 2012). However, these small-scale studies are not sufficient to permit assessment of the spending effects that would result from a broad expansion of palliative care in Medicare.

The evidence that increased palliative care could reduce spending is preliminary and would need to be confirmed through a large-scale demonstration before adopting a new benefit. Consistent with Option 3.3, such a demonstration could be combined with testing a narrower application of the current Medicare hospice benefit, under auspices of the CMMI, that reserves the more intensive supports of hospice for true end-of-life care.

OPTION 3.9

In conjunction with launching a large-scale pilot testing palliative care as a Medicare benefit, narrow the hospice benefit so that it serves only patients truly at the end-of-life with an identifiable short prognosis

Over the past decade, the average length-of-stay in hospice has increased from 54 days to 86 days, due almost entirely to a large increase in the proportion of hospice participants with lengths of stay longer than six months (MedPAC 2012b). In 2000, 10 percent of hospice patients had stays of 141 days or longer; in 2010, the top 10 percent all had stays of over 240 days. Among the concerns are the rapid change in the distribution of hospice diagnoses; lengths-of-stay greatly exceeding the physician’s expected prognosis certification of six months or less; and reports of seeming routine referrals to hospice from some nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Concerns have risen about rapid growth in the number of people “discharged alive” from hospice, which in some states approaches or exceeds 50 percent of beneficiaries entering hospice. This option, combined with the palliative care benefit described in Option 3.8, would restrict hospice eligibility to beneficiaries to those who are truly in the last weeks or days of life.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Providing a more broadly available palliative care benefit, paid at a much lower level than hospice currently, while also providing a more restricted-access hospice benefit, could reduce the long lengths-of-stay currently experienced in hospice while encouraging earlier referral to palliative care, which could be provided concurrently with curative care. Because palliative care does not involve bedside nursing, home health, or other “hands-on” services, but rather is focused on recommendations for symptom relief, shared decision making and care planning, and care coordination, this approach could counter the misuse of the current hospice benefit to provide additional hands-on staff in nursing homes and other residential care environments.

Creating two separate, complementary programs would add substantial complexity to care of those who would benefit from palliative care, only some of whom might also benefit from a more targeted hospice program. Instead of streamlining care for this high-need population, new regulatory barriers might be created because of the added complexity and concerns about possibly paying twice for similar services.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Jody Beauchamp, Valerie Cheh, Robert Schmitz, Peter Kemper, and John Hall. 2008. The Effect of the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) on Quality: Final Report, Mathematica Policy Research, February 12, 2008.

Randall Brown and David R. Mann. 2011. Best Bets for Reducing Medicare Costs for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries, Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2011.

Randall Brown et al. 2012. “Six Features of Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Programs that Cut Hospital Admissions of High-Risk Patients,” Health Affairs, June 2012.

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2012. Fact Sheet: CMS Initiative to Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations Among Nursing Facility Residents, 2012.

Center to Advance Palliative Care. 2011. America’s Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation’s Hospitals, May 2011.

Steven R. Counsell et al. 2009. “Cost Analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders Care Management Intervention,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, August 2009.

Benjamin Druss and Elizabeth Walker. 2011. Mental Disorders and Medical Comorbidity, Research Synthesis Report #21, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2011.

Federal Coordinated Health Care Office, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service (CMS). 2012. Medicare-Medicaid Financial Alignment Demonstration—Standards & Conditions, January 2012.

Leslie Foster, Robert Schmitz, and Peter Kemper. 2007. The Effects of PACE on Medicare and Medicaid Expenditures: Final Report, Mathematica Policy Research, August 29, 2007.

Richard Frank. 2013. “Using Shared Savings to Foster Coordinated Care for Dual Eligibles,” New England Journal of Medicine, January 2, 2013.

Gretchen Jacobson, Tricia Neuman, and Anthony Damico. 2010. Medicare Spending and Use of Medical Services for Beneficiaries in Nursing Homes and Other Long-Term Care Facilities: A Potential for Achieving Medicare Savings and Improving the Quality of Care, Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2010.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012. Medicare’s Role for Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries, April 2012.

Wayne Katon et al. 2008. “Long Term Effects On Medical Costs Of Improving Depression Outcomes In Patients With Depression And Diabetes,” Diabetes Care, 2008.

Harriet Komisar and Judy Feder. 2011. Transforming Care for Medicare Beneficiaries with Chronic Conditions and Long-Term Care Needs: Coordinating Care Across All Services, Georgetown University, October 2011.

Lewin Group. 2004. Medicaid Managed Care Cost Savings: A Synthesis of Fourteen Studies, Prepared for America’s Health Insurance Plans, July 2004.

Lewin Group. 2010. Individuals Living in the Community with Chronic Conditions and Functional Limitations: A Closer Look. Prepared for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning & Evaluation, United States Department of Health and Human Services, January 2010.

David Mancuso et al. 2010. Washington Medicaid Integration Partnership, RDA Report 9.100 Department of Social and Health Services, State of Washington.

Nancy McCall, Jerry Cromwell, and Carol Urato. 2010. Evaluation of Medicare Care Management for High-Cost Beneficiaries (CMHCB) Demonstration: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts General Physicians Organization (MGH), Final Report, Submitted by RTI International to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, September 2010.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2008. Report to the Congress: Reforming the Delivery System, June 2008.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2011. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2011.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2012a. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, June 2012.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2012b. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2012.

Diane Meier. 2011. “Increased Access to Palliative Care and Hospice Services: Opportunities to Improve Value in Health Care,” The Milbank Quarterly, 2011.

Diane Meier. 2012. Improving Health Care Value Through Increased Access to Palliative Care, National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, April 2012.

Harris Meyer. 2011. “A New Care Paradigm Slashes Hospital Use and Nursing Home Stays for the Elderly and the Physically and Mentally Disabled,” Health Affairs, March 2011.

National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. 2010. The Moment of Truth: Report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, December 2010.

Joseph G. Ouslander and Robert A. Berenson. 2011. “Reducing Unnecessary Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents,” New England Journal of Medicine, September 29, 2011.

Indira Paharia. 2012. “Behavioral Health Integration for Dual Eligibles in Managed Care, Presentation,” Molina Healthcare, 2012.

Deborah Peikes et al. 2012. “How Changes in Washington University’s Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Pilot Ultimately Achieved Savings,” Health Affairs, June 2012.

Elizabeth Stranges and Carol Stocks. 2010. Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations for Acute and Chronic Conditions, 2008. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, November 2010.

Jurgen Unutzer et al. 2008. “Long-term Cost Effects of Collaborative Care for Late-life Depression,” American Journal of Managed Care, February 2008.

Patient engagement

Options Reviewed

This section discusses two sets of policy options Medicare could adopt to increase patient and family caregiver engagement:

» Approaches and incentives for providers and plans

» Approaches and incentives for patients

Advances in medicine and expanded consumer options have added many responsibilities for patients and family caregivers even while improving the prospects for better outcomes. Increasingly, people are being asked to engage more actively and knowledgeably in many different aspects of their care to ensure that it is consistent with their preferences and delivers the best possible results. Increasing patients’ active and knowledgeable participation in their care is considered by some as a potentially powerful strategy to achieve the goals of improved patient experience, population health, and efficiency.3

Employers, health plans, and clinicians have developed approaches to patient engagement with mixed results. Many of these efforts are aimed at changing specific health-related behaviors, such as diet and exercise recommendations or compliance with treatment regimens. Others try to spread the use of shared decision making (SDM) to help patients participate more actively in their overall care. Still others seek to expand the transparency of health care costs and quality ratings to help consumers make informed decisions about providers and care (Catalyst for Payment Reform 2012).

People with Medicare are considered a prime group who could benefit from increased engagement. Many have multiple chronic conditions, are frequent users of medical care services, and often have additional vulnerabilities and limitations in navigating their health care options.

Background

Patient engagement has been defined as “actions people take for their health and to benefit from health care” and includes such behaviors as: finding good clinicians and care facilities; communicating with clinicians; paying for care; making good treatment decisions; participating in treatment; making and sustaining lifestyle behavior changes; getting preventive care; planning for care at the end of life; and seeking health knowledge (Gruman et al. 2010). As part of patient engagement, some experts also include patients’ financial responsibility for their health care decisions and utilization of care. In this respect, some have proposed to require people with Medicare to share more of the financial burden of Medicare spending to give them a greater stake in their health care (for an example of proposals in this area, see Antos 2012). This section does not address cost sharing in the context of efforts to enhance patient engagement in Medicare; for a discussion of options related to changes in Medicare beneficiary cost sharing, see Section One, Beneficiary Cost Sharing.

People’s willingness and ability to take action on their own behalf are influenced by many factors. For example, those who are seriously ill have difficulty coordinating their care among multiple clinicians. Patients with limited health literacy or math skills often cannot understand information regarding medications and other care regimens. Cognitive deficits and changes in hearing, sight, and mobility undermine people’s confidence in learning new ways to interact with the health care system. Patient participation in care is also affected by health care organizations and health professionals. It is daunting for people to ask questions of clinicians who cut them off or are unresponsive (Frosch et al. 2010). Information comparing insurance plans and benefits and the quality of facilities and doctors often is difficult to comprehend and the lack of price information poses additional barriers. In addition to all of these factors, the complexity of the Medicare program makes informed choice difficult: too many choices have been shown to reduce the quality of people’s decision making (Schwartz 2005).

At the same time, the potential benefits of care on people’s health and functioning can be negatively affected when they have low levels of active engagement. Different measures of the level of engagement by the population in general and of those over age 65 in particular show that only between one-quarter and one-third are active, confident, knowledgeable participants in their care (Williams and Heller 2007; Hibbard and Cunningham 2008).

Experts have suggested a number of ways to increase patient engagement that might reduce costs. One strategy is to support increased patient engagement through shared decision making for preference-sensitive treatment choices. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes several provisions in this area. For example, the ACA requires the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to establish a program that develops, tests, and disseminates certificated patient decision aids to help patients and caregivers better understand and communicate their preferences about reasonable treatment options, and funds an independent entity to develop consensus-based standards and certify patient decision aids for use by Federal health programs and other entities (Informed Medical Decisions Foundation 2010; Lee and Emanuel 2013). The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is focusing some attention in this area as well. These activities build on efforts by private employers, insurers, and patient advocates in both public and private health care settings.

A 2008 study suggested that implementing shared decision making for 11 procedures would yield more than $9 billion in savings nationally over 10 years (Lee and Emanuel 2013). There also is some evidence that being informed about risks and benefits of different test and treatment options may have an impact on the cost of some of patients’ decisions (Arterburn 2012). For example, an effort by leading physician organizations to identify tests and procedures that have little or no benefit to patients may encourage physicians to use more evidence-based approaches to tests and discuss recommendations with their patients, thus reducing unnecessary care (Cassel and Guest 2012).

While Medicare spending may not be reduced significantly through patient engagement alone, it may be difficult for some other efforts that reduce costs to be as effective as they otherwise could be without taking into account the role of the patient in financially consequential decisions about care. While no single policy option is likely to make all the difference in this area, a mix of policy changes could lead to changes in engagement among people with Medicare and those who care for them. There are no official cost estimates for the options discussed in this section, but the ways in which some of the options could generate savings to the Medicare program and beneficiaries are discussed below, where applicable.

Policy Options

Approaches and Incentives for Providers and Plans

OPTION 3.10

Increase provider payments for time spent interacting with patients in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage

Many have called for a rebalancing of provider payments, especially to physicians, so that cognitive services are more lucrative than they are today, especially in comparison to procedures. This option would change the balance in payments to increase sup-port for cognitive medicine, giving doctors and other clinicians more time to engage with their patients. This approach could foster greater efforts in shared decision making between providers and patients.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. The option could be designed to be budget neutral within the constraints of total physician fee schedule spending. This option might produce savings for both the Medicare program and beneficiaries to the extent that it helps patients, with encouragement from their providers, to manage their chronic conditions, avoid expensive and painful complications, and prevent new conditions from arising.

Discussion

Genuine patient engagement by clinicians—in shared decision making or discussion about strategies for managing chronic conditions, for example—takes time. Lack of time is a complaint of both patients and clinicians. It is possible that a shift in payment policy could reduce incentives to order or recommend tests and procedures, thus producing savings. For example, a cardiologist could, after discussion with a patient, try medication combined with diet and exercise to manage the problem, rather than immediately inserting a stent, an expensive and often overused approach to treating coronary artery disease. A number of decision support tools that summarize evidence and risk trade-offs targeted to physicians and patients have been developed to clarify treatment options, and more are being developed as part of the ACA (Lee and Emanuel 2013). Such tools might streamline complex shared decision making. Multiple strategies to support this kind of engagement could be adopted, including incentives for clinicians and, in particular, the ability of clinicians to invest the time and attention to help patients see the benefits of self-management, to develop the skills and strategies to act, and to increase patients’ confidence that they can be successful at it.

There is some concern, however, that merely providing a financial incentive for cognitive (as opposed to procedural) services would not guarantee that clinicians are able to use this time effectively or productively. There is evidence that many physicians lack the training, skills, or interest to engage in two-way discussions about treatment plans (Levinson, Lesser, and Epstein 2010). Acquiring these skills takes additional time and effort. Many patients, particularly older people who are comfortable with having their physicians maintain greater control over treatment decisions, may be similarly reluctant to abandon their traditional roles, especially when they feel ill and unable to participate in a shared decision making process.

OPTION 3.11

Emphasize patient access and use in Meaningful Use requirements for electronic medical records

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 supported adoption of health information technology—including electronic health records—by hospitals and clinicians through Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments and tied those payments to evidence of “meaningful use” of those records. Considerable attention has already been paid to this approach in the policies and actions of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology. This approach could be enhanced over time, with patient engagement requirements stepped up at each phase of the program.

This option would require traditional Medicare to enhance requirements for incorporating patient access and use in Meaningful Use requirements for Federally-funded electronic health/medical records (EHRs). Within Medicare Advantage, plans could be required to have network providers that met Meaningful Use standards for patient access to, and control over, EHRs.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Interoperable, transportable, electronic health records—and their off-shoot, personal EHRs—are expected to reduce some barriers to care coordination and continuity that now by default fall to patients and families who may be dealing with multiple co-morbidities. Clinician-patient communication and care coordination may be eased by meaningful access of patients to their health information through secure e-mail and other online tools. However, implementation of EHRs generally has been slow and physician adoption mixed. Currently, personal EHRs appear primarily to attract patients who are Web-savvy and already engaged in their health care (Miller 2012), which could make it difficult for providers to engage a greater number of their Medicare patients in this manner.

OPTION 3.12

Identify and incorporate measures of patient engagement in patient surveys and in provider and plan payment

Medicare increasingly is tying at least some portion of payments to providers and plans to their performance on sets of quality measures. But there are few measures of engagement in use (Williams and Heller 2007; Hibbard and Cunningham 2008). To address this issue, one option would be to require Medicare to identify or develop robust measures of patient engagement and use patient engagement metrics in pay-for-performance and shared savings plans. Medicare Advantage plans could be required to use patient engagement metrics as one aspect of selecting and rewarding providers. If such measures are based on patient reports, they could be added to the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) or the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System (CAHPS) survey.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Use of such measures of patient engagement could enable Accountable Care Organizations, medical homes, hospitals, and clinics to better target their efforts to support their patients’ participation in their care. Such data also could be used in comparative quality reports, reinforcing the notion that patient engagement is a priority and providing information to patients. However, developing and testing robust measures would take time and resources. Additional time would be needed to in-corporate them into public reports and to choose and implement specific measures as the basis for plan payment adjustment. Additional questions on surveys also would increase the burden for respondents, and would need to go through review and endorsement by the National Quality Forum.

OPTION 3.13

Promote greater involvement of Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs) in patient engagement strategies

The patient engagement metrics described above also could become a focal point in the Scope of Work (SOW) of the Medicare Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs). Medicare contracts with QIOs in each State and outlines its expectations through the SOW every three years. Attention to patient engagement could be incorporated for a series of SOWs. This option would promote greater involvement of QIOs with providers to increase opportunities and reduce barriers to patient engagement within traditional Medicare, using improvements in these patient engagement measures as QIO outcomes. Within Medicare Advantage, Medicare could require that implementation of patient engagement strategies become part of the QIO Medicare Advantage audit..

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

There is potential for this work to be linked to support of cost reduction efforts, such as reducing rehospitalization rates, by, for example, using emerging discharge planning strategies built on patient engagement foundations.4 However, QIO staff would need time to learn about engagement and how to help providers achieve it. Many QIOs have little experience working with patients and family members. They would need to either train their own staff in this area (which could be facilitated across QIOs by CMS through appropriate contractors) or acquire new staff who bring such experience. Either could be challenging and some would argue would shift the focus of QIOs from other priorities, such as reducing medical errors.

Approaches and Incentives for Patients

OPTION 3.14

Increase the use of comparative information within Medicare by improving the quality and promotion of public reports

Medicare has made large investments in developing measures of and public reports on health care performance and sharing the results with the public through its “Compare” websites. There is little evidence that many beneficiaries know about and use this information to choose plans or providers, however. While efforts are underway to improve performance reporting, standards for performance reporting could be developed by an independent expert group of report designers, sponsors, researchers, and users, and more vigorous action to promote their existence and location to ensure that they are responsive to audience needs could help.

This option would require Medicare to provide beneficiaries with more meaningful comparative quality and cost information using available and emerging evidence on the measures, language, and displays people find easiest to understand and use, and set standards that performance reports must meet. Within Medicare Advantage, plans could be required to provide members with detailed comparative quality information on clinicians and facilities in their network and provide accurate comparative out-of-pocket cost and quality information to their members for a range of services.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion