Retiree Health Benefits At the Crossroads

Frank McArdle, Tricia Neuman, and Jennifer Huang

Published:

Introduction

Retiree health benefit plans are an important source of supplemental coverage for roughly 15 million Medicare beneficiaries and a primary source of coverage for more than two million pre-65 retirees in the public and private sectors.1 But the state of retiree health coverage is at a critical juncture after decades of change, with still more to come on the horizon. The share of employers sponsoring retiree health coverage has declined and employers that continue to offer coverage are redesigning their plans on a virtually annual basis in response to rising health care costs. Ongoing concerns about costs, coupled with changes in Medicare, notably the addition of prescription drug coverage, and more recent changes made by the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), have triggered a major reassessment by employers of whether and in what form they should continue to offer retiree health benefits. Further, a number of policy proposals are under consideration that could have a significant impact on retiree health benefits and costs.

This report reviews the role of retiree health coverage for early and Medicare-eligible retirees, examines changes underway, and considers the outlook for the future. Specifically, the report:

- Presents an overview of retiree health benefits including the extent of such coverage for both pre-65 and Medicare eligible retirees, the manner in which it is provided, and the efforts by large employers to control retiree health costs;

- Discusses the implications of recent legislation, examining the aftermath of the Medicare Modernization Act’s Part D prescription drug benefit as well as the more recent provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that directly or indirectly affect employer-provided coverage for pre-65 and Medicare-eligible retirees (e.g., the provision that makes available new federal/state marketplaces and the provision that closes the Part D doughnut hole);

- Describes emerging strategies employers are adopting or considering to limit their retiree health costs, including changes in the arrangements for providing prescription drug coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees and shifts toward the use of defined contribution approaches and offering non-group coverage, including coverage made available through private exchanges; and

- Reviews current policy proposals under consideration that could affect the future of retiree health coverage, such as proposals to raise the age of Medicare eligibility, modify the benefit design and cost-sharing rules under traditional Medicare, impose a new surcharge on retiree health plans, and prohibit first dollar coverage.

The report concludes that under continuing pressure from rising costs, retiree health strategies of employers are now undergoing accelerated transitions and that the direction and pace of future changes will also be very sensitive to shifts in public policy. Several major trends stand out in particular, namely, growing interest in shifting to a defined contribution approach and in facilitating access to non-group coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees, and consideration by employers of using new federal/state marketplaces as a possible pathway to non-group coverage for their pre-65 retiree population. In general, most employers do not appear to be dropping coverage altogether, but the prevalence of retiree health coverage is expected to decline incrementally over time, assuming employers follow through on their interest in dropping coverage as reported in surveys.

Together these trends suggest that retiree health coverage is likely to be structured differently and play a smaller macro role in the future, but for the millions of workers and current and future retirees who do have employer-sponsored retiree coverage, changes that could weaken the prospects of their retirement security warrant close attention.

Report

Overview of Health Benefits for Pre-65 and Medicare-Eligible Retirees

Trends Among Employers Offering Retiree Health Benefits

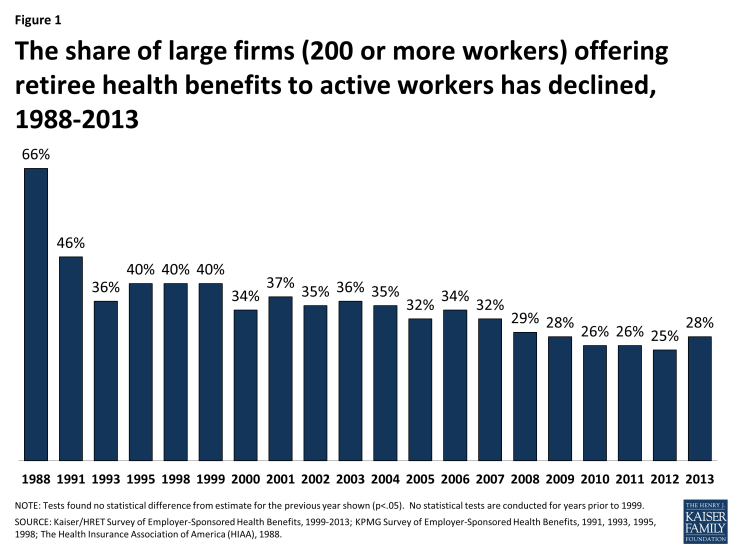

Over time, the share of large employers (with 200 or more employees) offering retiree health benefits has declined, and employers that continue to offer benefits have made changes to manage their costs, often by shifting costs directly or indirectly to their retirees. Since 1988, the percentage of large firms offering retiree health coverage has dropped by more than half from 66 percent in 1988 to 28 percent in 2013, according to the 2013 Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits (Figure 1). The biggest drop occurred between 1988 and 1991, after the Financial Accounting Standards Board required private sector employers to account for the costs of health benefits for current and future retirees. But ever since, there has been a more or less steady erosion in the percentage of firms offering retiree health coverage, dropping from roughly 40 percent of large employers in the mid-to late 1990s, to 28 percent of firms in 2013. Some firms elected to stop offering benefits (usually to future retirees first) while newer firms, and firms in the service and technology sectors, for example, never established the financial commitment to provide health benefits to their retirees. As a result of these changes, fewer than one in five workers today are employed by firms offering retiree health benefits.1

Figure 1: The share of large firms (200 or more workers) offering retiree health benefits to active workers has declined, 1988-2013

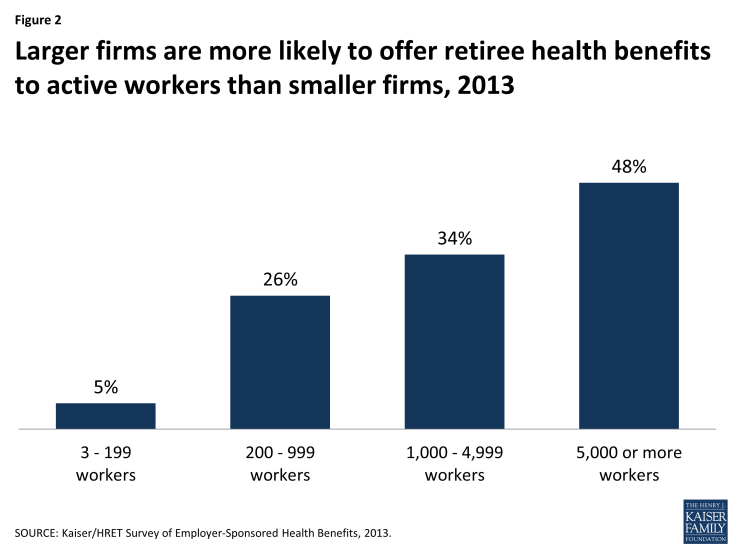

Large firms have always been much more likely than smaller firms to offer retiree health benefits to at least some of their former employees (Figure 2). Retiree health coverage is more typically offered to state and local government employees, and more often offered to employees in certain industries (such as finance) than to workers in the wholesale or retail industries, according to the KFF/HRET 2013 survey. Retiree health coverage is also more common among firms that pay higher wages, and more common among large unionized than non-unionized firms.

Figure 2: Larger firms are more likely to offer retiree health benefits to active workers than smaller firms, 2013

Coverage for Pre-65 Retirees

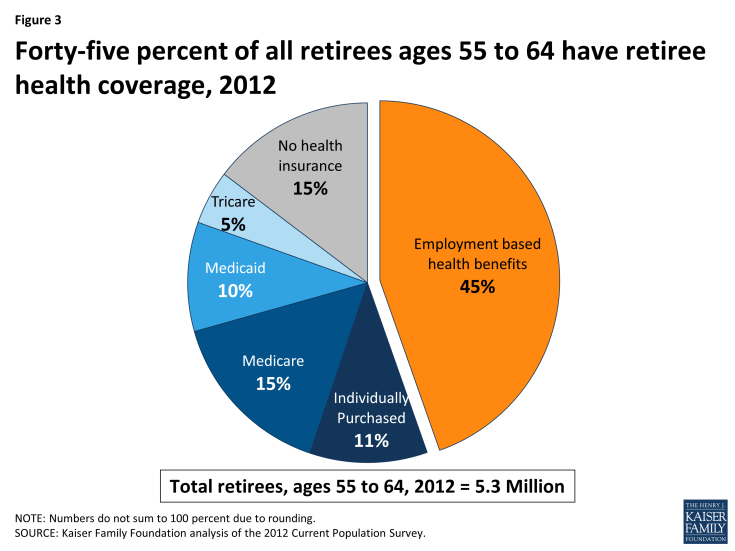

Employer-sponsored retiree health plans have historically played a vital role in contributing to retirement security for retirees who were too young to qualify for Medicare. In 2012, 45 percent of retirees ages 55 to 64 had health benefits from a former employer (Figure 3), reflecting a small decline from 2009, when 50 percent of early retirees had retiree health benefits.2 Prior to the availability of health marketplaces, insurance reforms, and subsidies provided by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), pre-65 retirees without access to employer-sponsored retiree health coverage or coverage from spouse had few good coverage options, as the availability of coverage for pre-65 retirees in the individual health insurance marketplace was unreliable, expensive, and subject to underwriting and potential denial of coverage. Though the cost of coverage for pre-65 retirees is substantially higher than for Medicare-eligible retirees, firms have been more likely to offer health benefits to pre-65 retirees. Among all large firms offering retiree health benefits, 90 percent of firms offered coverage to retirees under the age of 65, compared to 67 percent of firms offering coverage to Medicare-age retirees, according to the KFF/HRET 2013 employer survey.3

Large employers typically self-insure the benefits for pre-65 retirees and contract with health insurers to make available their provider network and administer the benefits and claims payments on a national basis. The employer may either combine the pre-65 retirees along with the active employees in the same risk pool, or break out the retirees in a separate risk pool. Most recently, as discussed further below, some employers that previously included active employees and retirees in the same plan have taken steps to create a separate legal plan for retirees only, as retiree-only plans are exempt from some of the more costly requirements of the ACA.

Employers offering pre-65 coverage typically offer the retirees the same health plan options that are available to active employees that, for large employers, would typically consist of a choice among several options, e.g., a PPO, an HMO, and (less frequently) a traditional indemnity plan. Such coverage is typically comprehensive and more generous than what Medicare currently provides, in that employer plans typically include a limit on out-of-pocket costs and provide a prescription drug benefit with no coverage gap. Often the employer will contract with a separate pharmaceutical benefit manager (PBM) to provide the prescription drug coverage (known as a “carve-out”), although sometimes the same insurer providing the medical benefits will also arrange to provide the prescription drug benefits (known as a “carve-in”).

A minority of large employers have changed their retiree health plans over the years in a move toward an account-based plan. With this approach, for example, an employer might credit employees between the ages of 40 and 55 with a fixed amount each year in a health reimbursement account (HRA), which the employees can then use to make their premium contributions to the health plan after they retire from the organization. Alternatively, an employer might offer employees high-deductible health plans as active workers and consider the eligible health savings account (HSA) as a vehicle that employees may use to accumulate funds that the employee can use toward retiree health expenses whether or not the employer actually sponsors a retiree health plan. HSA funds may not be used by pre-65 retirees to pay for retiree health plan premiums, but Medicare-eligible retirees can use HSA account balances to pay their Medicare premiums and premiums for retiree health plans (but not individually-purchased Medicare supplemental insurance policies, known as Medigap). The number of employers offering account-based health plans to active employers continues to grow, as does enrollment in such plans.

Premiums

The cost of providing retiree coverage to pre-65 retirees tends to be much higher than the cost of providing supplemental coverage to Medicare-eligible coverage because coverage for pre-Medicare retirees is primary rather than secondary. The average health benefit cost per retiree is roughly twice as much for pre-65 retirees as it is for Medicare-eligible retirees. According to data from Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, the average annual health benefit cost per retiree was $11,961 for pre-Medicare retirees and $4,716 for Medicare-eligible retirees, among employers with 500 or more employees who provided cost information for both 2011 and 2012.4 Another survey, the 18th annual Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Employer Survey on Purchasing Value in Health Care,5 reported the average cost for pre-65 retirees in 2013 (employer and retiree combined) was $9,064 for retiree-only coverage, and $4,583 for Medicare-eligible retirees. Typically, retirees are required to make a contribution toward the total premium, and in some instances, retirees pay 100 percent of the cost. According to the aforementioned Mercer survey, pre-65 retirees paid the full premium in 39 percent of the large employer plans (500 or more employees) offering retiree health benefits; employers paid the full amount in 12 percent of large employer plans. Among the remaining 49 percent of firms where the cost was shared, the average retiree contribution was 37 percent for pre-65 retirees. The results were similar among employers offering benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees.6

Coverage for Medicare-Eligible Retirees

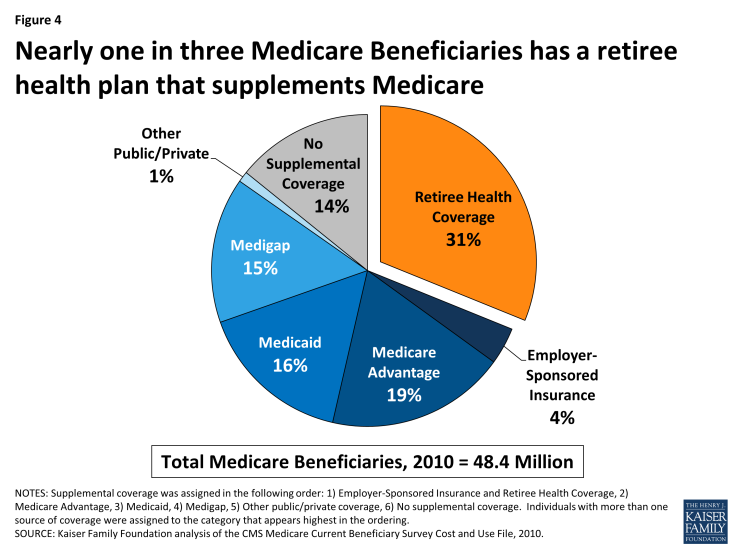

For retirees on Medicare, generally age 65 and older, employer-sponsored retiree health is the primary source of supplemental coverage (Figure 4). In 2010, nearly one-third (31%) of all Medicare beneficiaries had employment-based supplemental retiree health coverage. Another 4 percent were covered by an employer plan as an active worker, which means the employer plan was the primary payer.

Figure 4: Nearly one in three Medicare Beneficiaries has a retiree health plan that supplements Medicare

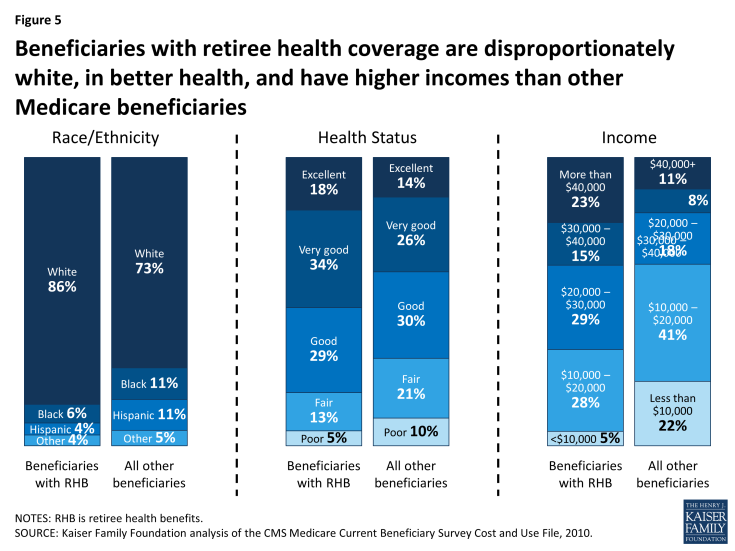

In general, Medicare beneficiaries with employer-sponsored retiree health benefits tend to have higher incomes than others on Medicare, are more likely to be white than black or Hispanic, and in relatively good health (Figure 5). The prevalence of retiree health coverage also varies geographically. Medicare beneficiaries living in the New England region are more likely than those in the South Atlantic and West North Central regions to have retiree coverage. The share of Medicare beneficiaries with retiree health benefits ranges from a high of 38 percent in the New England region (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT) to a low of 28 percent in the South Atlantic region (DC, DE, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV) and the West North Central region (IA, KS, MN, MO, ND, NE, SD) (see Appendix Table 1 for the share of Medicare beneficiaries by region).

Figure 5: Beneficiaries with retiree health coverage are disproportionately white, in better health, and have higher incomes than other Medicare beneficiaries

Employer-provided retiree health coverage fills significant financial gaps for Medicare-eligible retirees. Medicare has relatively high cost-sharing requirements, and unlike typical employer plans, has no limit on out-of-pocket spending for services covered under Part A or Part B. Until 2006, Medicare did not cover outpatient prescription drugs, and even today, the Medicare drug benefit includes a coverage gap, or “doughnut hole” that will be phased down by 2020. Employer-sponsored retiree health plans help minimize the financial exposure of Medicare-eligible retirees by paying a portion of Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements, and in some instances, by paying for items that are not otherwise covered by Medicare (e.g., eyeglasses). By one calculation, a 65-year-old couple with Medicare retiring in 2013 without employer-sponsored retiree health coverage is estimated to need $220,000 to cover medical expenses throughout retirement, in addition to costs they may incur for over-the-counter medications, dental services, and long-term care.7

Employers use a variety of approaches to provide health benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees, as described below.

Self-Insured Employer Plans Supplement Medicare Benefits. The most common arrangement is where an employer sponsors a group plan that supplements Medicare, such as a preferred provider organization (PPO) or an indemnity plan, with a more generous package of medical and prescription drug benefits than traditional fee-for-service Medicare. For example, retiree health plans typically have a limit on out-of-pocket spending, unlike traditional Medicare, and will cover a larger share of retiree expenses for covered services that exceed the out-of-pocket limit. These plans are secondary to Medicare, which means that Medicare is the primary payer for each medical claim, and the employer plan will pay its portion of the claim after Medicare benefits are awarded. Typically the employer plan will coordinate with Medicare benefits using a “carve-out” approach, i.e., the employer plan calculates what it would pay toward the claim and then reduces its payment by the amount that Medicare pays.

Prescription Drug Coverage. With respect to prescription drugs, employer plans typically provide prescription drug coverage in conjunction with other medical benefits, and often these benefits are more generous than the standard Part D benefit (e.g., no coverage gap). Employers have the option to provide prescription drug benefits directly through an employer plan and receive a federal retiree drug subsidy (RDS) payment for offering qualified prescription drug coverage (that is, coverage that is at least equivalent to the Part D standard benefit). Alternatively, the employer may contract with a Medicare Part D prescription drug plan (PDP) on a group basis to provide prescription drug coverage to Medicare-eligible retirees, for which the employer pays a negotiated premium in addition to what the PDP receives from Medicare under Part D. Often the Part D plans receive a waiver from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide coverage exclusively to the employer group and the employer plan separately supplements the Part D plan benefits, a combination known more technically as Medicare Part D Employer Group Waiver Plans (EGWP) plus Wrap. Under these arrangements, employers contract with a Medicare Part D plan to provide benefits solely to the employer’s retirees, based on the standard benefit design, and the employer offers a secondary plan that supplements the first (waiver) plan to provide more generous drug coverage.8

Medicare Advantage Plans. Employers also have the option to contract with a Medicare Advantage plan (such as an HMO or PPO) on a group basis to provide supplemental benefits to its retirees, in conjunction with Medicare-covered benefits provided under that plan. With this approach, the employer plan negotiates with the managed care organization to define the supplemental benefits that are provided to their retirees. The managed care plan receives a capitated payment from Medicare for each retiree as well as the incremental additional employer plan premium for the negotiated supplemental benefits. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established a federal waiver process to give employer plans greater flexibility to contract with Medicare Advantage plans by allowing such plans to limit enrollment to beneficiaries in the employer group and making it easier for an employer plan sponsor that wants to adopt a uniform strategy for covering retirees on a national basis.

Employers electing this option have benefitted from relatively high Medicare payments to group plans, which has helped to reduce the cost of providing extra benefits for their retirees, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).9,10 While employer-sponsored Medicare Advantage plans are subject to the same benchmarks as other Medicare Advantage plans, and are not eligible to receive bonus payments, they tend to receive higher federal payments than non-employer plans. This is because employer plans have an incentive to submit bids closer to the benchmark, while non-group plans have an incentive to bid below the benchmark.11 According to MedPAC, the average bid among employer group Medicare Advantage plans in 2014 was substantially higher than the average bid submitted by non-employer plans (95 percent and 86 percent of their benchmarks, respectively, weighted by projected enrollment), and as a result, average Medicare payments to employer-sponsored Medicare Advantage plans in 2014 are higher than for other Medicare Advantage plans.12

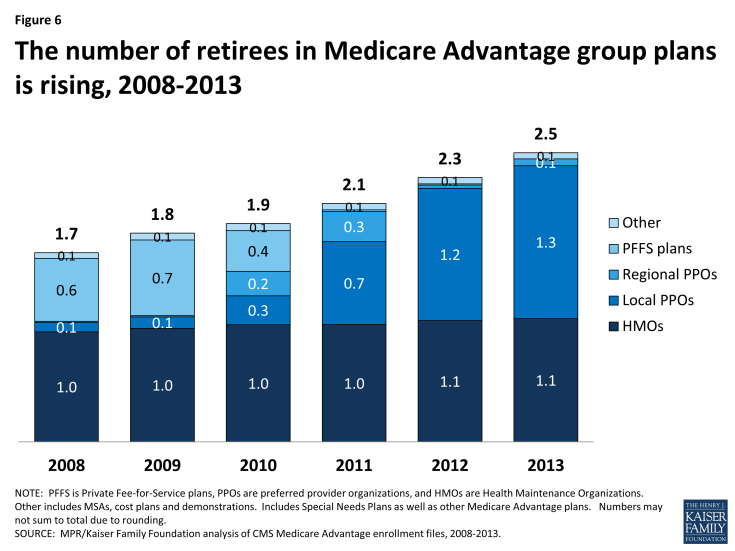

Once the employer contracts with the Medicare Advantage plan to provide benefits, the Medicare Advantage organization interacts directly with the enrolled retirees and with federal authorities, handles the administration and compliance responsibilities, and collects applicable Medicare payments. Today, 2.5 million Medicare beneficiaries are covered under group-based Medicare Advantage plans, up from 1.7 million in 2008 (Figure 6).13

The Administration in its FY2014 and FY2015 budgets has proposed to align payments for group plans with other Medicare Advantage plans for an estimated savings to Medicare of nearly $4 billion over 10 years .14,15 Similarly, in its 2014 report to Congress, MedPAC recommended a change in payment policy that would essentially reduce Medicare payments to employer group plans by basing them on the bids submitted by non-group plans, similar to the way it is done for Part D. It is unclear how these proposed changes in payment policy would affect future enrollment. Similarly, it is unclear what the effects would be of other recently-proposed rules from CMS that would make policy changes to the Medicare Advantage and Part D regulations without differentiating employer group plans.16

Health Reimbursement Accounts and Private Exchanges. A newer trend, discussed in greater detail below, is where an employer facilitates retiree access to Medicare Advantage, a Medicare Part D or Medigap plans offered through a private exchange on a non-group basis. Employers electing this approach typically make a defined financial contribution to a health reimbursement account (HRA) that is used by retirees to pay premiums in the plan selected by the retiree. Depending on the plan, the HRA may also be used to pay for out-of-pocket medical expenses. For these arrangements, employers may contract with a third party administrator or facilitator known as a “private exchange” to provide support and assistance to retirees in choosing from among a broad array of non-group plans of different types, plan designs, and costs.

Premiums

Typically, retirees are required to make a contribution toward the total premium, and in some instances, retirees pay 100 percent of the cost. According to Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, retirees ages 65 and older paid the full premium in 40 percent of the large employer plans offering retiree health benefits. Conversely, large-employers paid the full amount in 14 percent of plans reported in the Mercer survey. Among the remaining 46 percent of plans where the cost was shared, the average retiree contribution was 38 percent for Medicare-eligible retirees. The results were similar among employers offering benefits to pre-Medicare retirees.17

Strategies Used by Employer to Constrain Retiree Health Costs

Surveys conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and others have documented a trend among employers providing retiree health coverage of modifying their programs in an ongoing attempt to control retiree health costs.18 In addition to outright terminations of coverage, key changes reported by employers over the years include:

- Capping the employer’s contribution (or limiting the amount of the employer share of the total cost) for retiree health benefits;

- Tightening eligibility requirements, e.g., raising minimum age and service requirements;

- Raising retirees’ premiums and cost sharing, including changes that essentially eliminated first-dollar coverage for retirees;

- Eliminating coverage for future retirees, typically first for new hires, in some cases for current employees and, far less frequently for current retirees; and

- Optimizing savings from Medicare prescription drug coverage.

Yet despite such efforts, retiree health costs remain a significant concern for the dwindling number of employers that continue to offer this coverage for current workers and, failing that, for those covering a closed group of retirees with grandfathered coverage. For additional changes under consideration by employers, see the “Emerging Strategies for Employers Offering Retiree Health Coverage” section on page 12.

Implications of Recent Legislation for Retiree Health Coverage

Changes for Pre-65 Retirees

The Affordable Care Act of 2010

The ACA includes numerous provisions that directly or indirectly affect retiree health plans for pre-65 retirees, including, for example, the creation of the temporary Early Retiree Reinsurance Program and creation of a new marketplace where pre-Medicare retirees can for the first time obtain health coverage on a guaranteed issue basis with no pre-existing condition exclusions and on relatively favorable financial terms without having an employer directly sponsor a retiree health plan. A discussion of these ACA provisions follows.

Early Retiree Reinsurance Program

The ACA established the Early Retiree Reinsurance Program (ERRP) as a temporary program with $5 billion in total funding from its start on June 1, 2010, until the program was scheduled to end no later than January 1, 2014. Noting the decline in the availability of group health coverage for retirees age 55 to 64, the intent of ERRP was to try and stabilize coverage by providing financial assistance to plan sponsors offering retiree health benefits by reimbursing for 80 percent of claims between $15,000 and $90,000 for early retirees ages 55 to 64 and their spouses, surviving spouses, and dependents.

The demand for such assistance quickly outpaced the available funding. Due to the overwhelming response from public and private employers and union plans, the program ceased accepting applications on May 6, 2011. Six months later, on December 13, 2011, CMS announced in the Federal Register that based on the projected availability of ERRP funding, it exercised its authority to deny ERRP reimbursement requests, in their entirety, that include claims incurred after December 31, 2011.1 ERRP payments must be used to reduce the costs of plan participants or plan sponsors, and may not be used as general revenue. In a Federal Register notice of March 21, 2012, CMS formalized its expectation that a sponsor will use ERRP reimbursement funds as soon as possible, but not later than December 31, 2014.2 Even though the ERRP was intended to be temporary, the fact that claims for reimbursement so quickly exceeded funds available under this program illustrates the pent-up pressures among employers to seek financial relief from rising retiree health costs and underscores their continuing interest in pursuing alternative ways of loweringtheir retiree health costs as discussed further below under “Emerging Strategies for Employers Offering Retiree Health Coverage.”

Insurance Reforms, New Marketplaces and Premium and Cost-Sharing Subsidies

Effective January 1, 2014, new health care marketplaces (public exchanges) have become available in every state, either as federally-facilitated marketplaces or as marketplaces established by the states themselves. These new marketplaces have created another potential avenue through which pre-65 retirees can obtain coverage with or without financial support from the employer. Previously, there was no reliable individual insurance market for pre-65 retirees, and employer-provided health benefits enabled pre-65 retirees to retire with the confidence of having continued health coverage in retirement. Now, access to coverage for pre-65 retirees is guaranteed whether or not the employer provides a health plan, the benefits are comprehensive, the limits on age rating are favorable to retirees, and premium credits and cost sharing federal subsidies may be available to certain retirees who qualify based on income and do not receive an employer contribution..

Excise Tax on High-Cost Health Plans

The ACA established, effective in 2018, a non-deductible excise tax on high-cost employer-sponsored plans, which, for active employees and retirees ages 65 and older, is equal to 40 percent of the value of health coverage in excess of $10,200 for self-only coverage and $27,500 for family coverage. (This tax is sometimes referred to unofficially as the tax on so-called “Cadillac” health plans.) The law allows a higher threshold before the tax kicks in for qualified retirees, defined as any individual who is receiving coverage by reason of being a retiree, has attained age 55, and is not Medicare-eligible. For pre-65 retirees, the excise tax applies to coverage in excess of $11,850 for self-only coverage and $30,950 for family coverage. In determining the applicable cost of employer-sponsored coverage to retired employees, the plan may elect to treat pre-65 retirees and retirees ages 65 and older as being “similarly-situated beneficiaries,” meaning that the costs for both groups can be blended together. Since the cost of retiree coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees is considerably less than for pre-65 retirees, such blending would usually lower the average cost of the retiree plan for purposes of determining whether there is any taxable excess. Regulations setting forth how all this will work have yet to be issued. And although the tax is not effective for several years, many plan sponsors are generally projecting where their costs will be in 2018 and have already been making adjustments to scale back benefits so that they will not be subject to the tax.3 In addition, this tax has generally been reflected in the accounting of these benefits in financial statements since the passage of the ACA. With respect to retiree health plans, this pressure may be especially strong where the employer offers pre-65 coverage but does not also offer coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees that can be used to reduce the average cost.

Exemption for Retiree-Only Plans

Retiree-only plans are generally not subject to many of the ACA requirements for group health plans and market reforms. This is based on what had been a long-standing exemption for such plans under ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code. A group health plan is considered to be retiree-only plan if it has fewer than two participants who are active employees, and typically such plans are reviewed with legal counsel to ensure that the plan is governed by separate plan documents, summary plan description, administration and required reporting (e.g., Form 5500) with no commingling of assets. Because of this significant exemption, retiree-only plans are not required to comply with some of the more costly requirements of the ACA, e.g., extending medical plan eligibility to adult children up to age 26, no annual or lifetime dollar limits on essential health benefits, covering preventive health services with no patient cost sharing, the four-page uniform summary of benefits and coverage, as well as certain other provisions.4 The exemption also applies to nonfederal government retiree-only plans.5 As a result of the new ACA requirements and the exemption for retiree-only plans, many employers that had included retirees in the same plan with active employees had a financial incentive to create a separate legal plan for retirees and avoid the ACA cost increases with respect to the retirees. That change would allow the employer to continue providing the same coverage to retirees as was provided prior to the ACA. For example, under a retiree-only plan, employers who did not previously offer coverage to retirees with adult children under age 26 would not be required to comply with the ACA requirement to provide coverage for these children.

The exemption is also important because it allows stand-alone health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs) for retiree-only plans, which can be used to pay retiree premiums for group or individual health insurance coverage. Without the retiree-only exemption, stand-alone HRAs would violate the ACA’s ban on annual dollar limits and face other regulatory restrictions. (Under current rules, without the retiree-only exemption, HRAs must be integrated with a group health plan and cannot be used to pay premiums for individual health insurance coverage or coverage through a federal or state exchange.)

However, if an HRA is used to pay for federal/state health exchange coverage for a pre-65 retiree, that retiree is not eligible for federal premium credits or cost sharing subsidies because the HRA for this purpose is considered to be employer-sponsored coverage that bars the retiree from receiving federal subsidies. The same issue does not apply to Medicare-eligible retirees because they are not generally permitted to purchase coverage in a new exchange, and are ineligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies.

Dedicated New Fees

The ACA also assesses two new sets of temporary, dedicated fees, one of which is relatively small and the second of which is considered substantial by large employers. The first is a temporary fee to fund the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), assessed at $1 per covered life in the first year it is in effect (plan years ending on or after October 1, 2012), $2 per covered life in the second year, and indexed thereafter until the fee sunsets in plan years ending before October 1, 2019. The fee applies to coverage provided to retirees, including retiree-only plans.6 The second is a temporary fee in the form of a transitional reinsurance fee payable by insured and self-insured group health plans offering “major medical coverage” in calendar years 2014 through 2016, funds intended to help stabilize premiums in the ACA reformed individual market. The fee is $63 per covered life in 2014. The fee applies to pre-65 coverage, even if the plan is a retiree-only plan,7 but does not apply to coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees because, based on the Medicare Secondary Payer rules, Medicare is the primary payer.

In addition, the ACA assesses a new, permanent fee beginning in 2014. The fee is called the Health Insurance Industry Tax and is intended to help fund premium tax subsidies for low-income individuals and families who purchase health insurance through the health insurance marketplaces. The fee is expected to collect $8 billion in 2014 and increasing annually up to $14.3 billion in 2018 with increases in the fee thereafter tied to the rate of premium growth. The fee applies to insured (but not self-insured) group health plans, Medicare Advantage plans and Part D plans; Medigap plans purchased by individuals (without subsidies from former employers or unions) are not subject to the fee. As with the PCORI fee and the reinsurance fee, there is nothing in the ACA or in the regulations that prevents plans from increasing premiums to recover the amount of the fee.

Changes for Medicare-Eligible Retirees

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

Historically, retiree health plans filled what had been until 2006 a major gap in traditional Medicare coverage, namely, the absence of prescription drug coverage. The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) established a voluntary outpatient prescription drug benefit, known as Part D, that went into effect in 2006. All 52 million elderly and disabled beneficiaries now have access to the Medicare drug benefit through private plans approved by the federal government, either stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage prescription drug (MA-PD) plans (mainly HMOs and PPOs) that cover all Medicare benefits including drugs. Part D sponsors offer plans with either a defined standard benefit8 or an alternative equal in value (“actuarially equivalent”), and can also offer plans with enhanced benefits.

The MMA included provisions to encourage employers to maintain prescription drug coverage for their retirees, in conjunction with other medical benefits. As noted earlier, the law provides federal subsidies to sponsors of certain qualified prescription drug plans (employer plans that offer drug benefits that are at least as good as the standard Medicare benefit). The federal subsidies equal 28 percent of allowable drug costs, which for most employers amounted to a retiree drug subsidy (RDS) payment of $500 to $600 per retiree.9 In addition, until recently, the law allowed plan sponsors to exclude the federal RDS payment from income and still deduct the full cost of retiree health benefits, in effect allowing employers to take a larger tax deduction than under the general tax rule, whereby taxpayers generally may not deduct costs that are reimbursed. The subsidy and favorable tax treatment were designed to discourage employers from dropping prescription drug coverage from their retiree health benefits and to minimize any disruption in drug coverage for retirees in employer-sponsored plans.

Initially, the vast majority of employers offering retiree health benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees chose to maintain drug coverage and accept the RDS. In 2006, 7.2 million Medicare beneficiaries with employer-sponsored retiree health benefits had claims reimbursed under the RDS – a figure that has dropped steadily since then, and is projected to drop sharply in the future, as described below.10

The Affordable Care Act of 2010

The ACA, though mainly designed to improve coverage for individuals younger than age 65 and not yet on Medicare, included changes to Medicare that are expected to affect employer-sponsored coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees. On the one hand, improvements in Medicare benefits, particularly provisions that close the “doughnut hole,” are expected to reduce out-of-pocket expenses for Medicare beneficiaries and consequently the costs of employer-provided retiree health plans that supplement Medicare.11 But on the other hand, certain other changes, notably the change in the tax treatment of the RDS, may accelerate changes in employer-sponsored coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees.

Closing the Medicare Part D “Doughnut Hole”

From a retiree health perspective, the most significant improvements in Medicare concern the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits. Specifically, the ACA gradually phases in coverage in the Medicare Part D “doughnut hole,” eventually reducing what beneficiaries pay in the gap from 100 percent of total drug costs in 2010 to 25 percent in 2020 for both brand and generic drugs, at which point the enrollee would qualify for catastrophic drug coverage. Beginning in 2011, pharmaceutical manufacturers were required to provide a 50 percent discount off negotiated prices on brand-name drugs and biologics for Part D enrollees with spending in the coverage gap. In 2011, the coinsurance for generic drugs began to phase down, and in 2013, the coinsurance for brand-name drugs began phasing in. The ACA also reduces the catastrophic coverage threshold between 2014 and 2019, which provides relief to enrollees with high drug costs. Together, these improvements provide a substantial reduction in the cost of providing drug coverage to retirees for employers who contract with PDP or MA-PD plans. The financial attractiveness of employer plans using the RDS, however, was reduced in part by changes in the tax treatment of the RDS also included in the ACA.

Repealing the Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS) Preferential Tax Treatment

The ACA repealed the provision that allowed plan sponsors to disregard the RDS payment for purposes of determining whether a deduction is allowable for subsidized costs, effective in 2013. Plan sponsors will be able to continue to exclude RDS payments from gross income, but will be subject to the normal rules disallowing a deduction for expenses for which the sponsors are reimbursed, in effect, making the RDS payment taxable. Even though the change was not effective until 2013, accounting rules required certain employers to record an accounting charge in their 2010 financial results to reflect the impact of the change in RDS tax status.

Employers who take the RDS do not benefit from the improvements in Medicare drug benefits in that RDS claims are ineligible for the 50 percent brand-name drug discount. Furthermore, RDS plans do not receive the financial benefits that flow to other Part D plans from the closing of the doughnut hole. Although RDS plans are at least actuarially equivalent to Medicare drug coverage, the RDS payment is in lieu of Part D plan coverage. Retirees in an RDS plan only receive the employer drug coverage and do not receive Part D plan benefits. The formula for calculating the RDS payment to the employer plan sponsor was not changed under the ACA. It remains based on the percentage of the retiree’s drug costs under the employer plan, not on what Part D pays. In 2014, for each RDS plan, subsidy payments to a plan sponsor for each qualifying covered retiree will generally equal 28 percent of allowable retiree costs under the employer plan between $310 and $6,350. The cost thresholds are indexed but the 28 percent remains fixed. So closing the doughnut hole does not result in a higher RDS subsidy even though the doughnut hole will be closing over time for other Part D drug plan participants.12

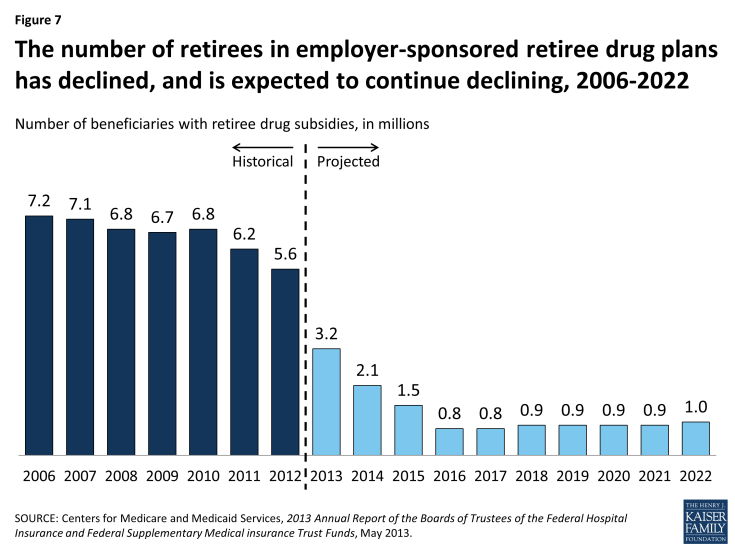

The number of Medicare beneficiaries with claims reimbursed under the RDS dropped from 7.2 million in 2006 to 6.8 million in 2010, even before the ACA was enacted, and has continued to decline since then to 5.6 million beneficiaries in 2012 (Figure 7). The Medicare Trustees project an even sharper decline starting in 2013, when just 3.2 million Medicare beneficiaries are expected to have RDS claims, falling to just 0.8 million by 2016.13

Figure 7: The number of retirees in employer-sponsored retiree drug plans has declined, and is expected to continue declining, 2006-2022

The expected drop in employers taking the RDS is due to several factors, in addition to the change in tax treatment that took effect in 2013. For some employers, the operational and administrative hassles associated with the subsidy program made alternative approaches more attractive, such as contracting with a Medicare PDP to administer additional prescription drug coverage to their retirees.14 Part D insurers have become more sophisticated in the administration of the employer group waiver programs, making it easier for employers to take advantage of new subsidies in the Part D program (e.g., pharmaceutical rebates and the closing of the doughnut hole). Employers, especially those with caps on their financial contribution toward retiree health benefits, have understood that over time, as the cap was hit and the retiree’s share of the total cost increased, the plan would eventually cease to satisfy the test of offering drug benefits that were actuarially equivalent to Medicare, which is required to qualify for the RDS. Public employers had their own set of reasons to shift away from the RDS. A new set of accounting rules (Statements 43 and 45) issued by the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) applied to state and local governments (including public universities and colleges) on a phased-in basis beginning in December 2006. These rules prohibit public entities from reflecting any accounting savings associated with the RDS 28% subsidy, although the rules do allow the accounting savings to be reflected for other Part D coordination approaches (e.g., supplemental/wraparound PDP coverage). These GASB accounting rules led public entities to more strongly consider alternative Medicare Part D coordination approaches as a way of managing costs well before the enactment of the ACA.15

Reducing Medicare Payments to Medicare Advantage Plans

In response to well-documented concerns about overpayments to plans, the ACA phases in reductions in future payments to Medicare Advantage plans. Although the provision does not specifically target group plans, group plans are nonetheless affected by the reduced payments to plans in the same manner as other Medicare Advantage plans.

A relatively small share of all Medicare beneficiaries with Medicare Advantage coverage — about 18 percent — are covered by group Medicare Advantage plans. Group enrollment rose by 9.4 percent in 2013, at about the same rate as the 9.8 percent growth in individual enrollment. The phase down in payments could discourage employers from maintaining or considering new arrangements with Medicare Advantage plans to provide benefits to retirees – although the number of retirees in Medicare Advantage group plans has continued to rise. Employers have for the past decade been somewhat hesitant to build their retiree health strategy around Medicare Advantage plans after building strategies around what were then called Medicare Risk HMOs in the past, only to experience subsequent dislocations when health insurers withdrew from many markets after legislated reductions in Medicare payment rates. Thus, employers currently sponsoring or considering sponsoring group Medicare Advantage plans will be assessing the potential effects on employer costs of future Medicare Advantage payments and the extent to which health insurers may withdraw plans from selected markets, as some already have said they are.16 In addition, employers will be watching the future of the Administration proposal to modify payments to employer group waiver plans as part of its FY 2015 Budget, although the provision was previously proposed in the FY 2014 Budget and not enacted into law.

Emerging Strategies for Employers Offering Retiree Health Coverage

Employers are moving forward with more alternative strategies for their early retirees and Medicare-eligible retirees, as they continue seeking to manage costs and watch for future developments in federal policy. In addition to ongoing changes in eligibility, benefit design, premiums, and cost-sharing, employers are moving in new directions, some of which entail incremental changes in the way the group prescription drug benefits are offered and others of which entail a more substantial break from the past by shifting to non-group coverage for medical and drug coverage.

Strategies for Pre-65 Retirees

Employers offering coverage to pre-65 retirees are focusing on strategies to avoid or minimize the impact of the excise tax on high cost plans included in the ACA (discussed above). Although the tax applies to plans for active employees, as well as pre-65 and Medicare-eligible retirees, there is a focus on pre-65 coverage because of its relatively higher cost. And even though the tax takes effect under the ACA in 2018, employers must begin to account for any material impact the tax may have on their retiree health programs in today’s financial statements.

According to the 2013 Aon Hewitt retiree health survey, some of the most common strategies employers are considering to mitigate the effects of the excise tax include: (1) lowering the cost of the plan through plan design changes, e.g., higher deductibles, coinsurance and copays, or using a high deductible health plan that may be Health Savings Account (HSA) eligible, favored by 29 percent of large employers; (2) using a defined contribution approach to support pre-65 retirees obtaining coverage through the federal/state marketplaces, favored by 22 percent, and (3) eliminating pre-65 coverage, favored by 13 percent. In terms of the longer-term future, employer sponsors of pre-65 coverage in the same survey expressed a roughly three way split in terms of favoring using a defined contribution strategy with federal/state marketplaces (34%), making no change in strategy (33%), and eliminating pre-65 coverage (30%).1

Public Exchanges and Marketplaces

With the advent of the federally-assisted and state ACA marketplaces, a number of benefit consultants and e-brokers are offering employers the service of facilitating coverage in the ACA marketplaces for employees and retirees not covered under the employer’s health plan, e.g., part-time employees working fewer than 30 hours, and pre-65 retirees, if the employer does not offer a retiree health plan.2 A number of employers have already announced or are seriously considering providing their pre-65 retirees a defined contribution that can be used to purchase coverage in the federal/state ACA marketplaces. Observers predict this will be a major trend going forward and in some cases see the ACA marketplaces as further displacing employer-provided coverage for pre-65 retirees.3 In a recent survey of 595 employers by Towers Watson and the National Business Group on Health, conducted between November 2013 and January 2014, nearly two-thirds of those that offer access to a retiree health plan today say they are likely to eliminate those programs in the next few years and steer their pre-Medicare retiree population to the public exchanges.4

A separate question may be how many pre-65 retirees with employer coverage might themselves choose to decline employer retiree coverage and enroll in a federal/state marketplace. According to a survey by the National Business Group on Health, more than one-fourth (26%) of large employers felt that some pre-65 retirees might opt to join exchanges.5 Some actuaries are forecasting that pre-65 retiree participation rates in employer-sponsored plans will likely decline in the future, given favorable age rating in marketplace plans and in particular for employer plans with: (1) capped or lower employer contributions toward premiums; (2) covered populations with lower income retirees, due to federal premium subsidies available in the health care marketplaces; and (3) excise taxes on high-cost plans passed through to retirees.6 In particular, with respect to the 40 percent of retiree health plans wherein some surveys indicate retirees pay the full cost of premiums, individual health insurance coverage in the federal/state marketplace could well be cheaper (though potentially less generous) than the employer plan.

Private Exchanges

As an alternative to the federal/state marketplaces, employers may also consider offering group coverage through private exchanges for pre-65 retirees. In the last few years, a growing number of benefit consultants and insurers have launched — or soon plan to launch — a private exchange through which active employees purchase coverage. These exchanges are similar in concept to the private Medicare exchanges (described below) except that the active employees typically have access to insured or self-insured group products rather than non-group medical plans. Like the exchanges set up for Medicare-eligible retirees, these private exchanges can be single carrier or multi-carrier, and the employer contribution is usually in the form of a defined contribution amount, which can be used toward buying more generous or less expensive coverage available through the private exchange. Employers continue to offer the coverage, but it is outsourced through the private exchange, so the employer spends less on administration. The defined contribution approach results in more predictable costs for employers. Employees may or may not be exposed to greater cost increases in the future, depending on the rate of future increases in premiums and the share of that increase paid by the employer. The hope is that particularly in the case of multi-carrier exchanges, greater competition among insurers may help lower the future rates of increase. While these newer exchanges are typically not dedicated to pre-65 retirees, some of them will accept the employer’s pre-65 retirees along with the active employees.

Strategies for Medicare-Eligible Retirees

Employers offering retiree health coverage to Medicare-eligible retirees are also exploring alternative strategies to take the best advantage of the improvements in Medicare drug coverage, or transitioning to non-group arrangements for retirees to obtain medical and drug coverage.

Medicare Part D Group Waiver Plan (EGWP) plus Wrap

For employers choosing to continue offering retiree health plans on a group basis, the changes in the tax treatment provisions of the RDS coupled with the improvement in Medicare drug benefits have prompted many employers to replace their RDS strategy for Medicare-eligible retirees with what is called a Medicare Part D Employer Group Waiver Plan (EGWP). The most common EGWP strategy – EGWP + Wrap – consists of two separate but integrated plans. The primary plan is the EGWP – a Medicare Part D plan offered by contract solely to the employer’s retirees – with the standard Medicare Part D plan design and the coverage gap. The secondary plan is an employer group plan that supplements or “wraps around” the EGWP so that the combination of the two benefits basically replicates the drug benefits that had previously been available to retirees under the RDS. Both plans may be (and often are) self-insured. The 2013 Trustees report estimates that the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries in these employer-sponsored plans will increase from about 9 percent in 2012 to about 20 percent in 2016 and beyond. The Trustees expect that such plans will offer additional benefits beyond the standard Part D benefit package.7

To reap the financial benefit of the 50 percent manufacturer discount on brand name drugs, under EGWP + Wrap, any brand drug coverage in the coverage gap is provided by the supplemental “wrap” plan, not the Part D plan. Recent CMS guidance clarifies, however, that the 50 percent manufacturer discount is also available if the employer chooses to contract for an “enhanced” EGWP design for its retirees that may provide drug benefits close to the previous RDS plan design but without a separate wrap-around plan. This effectively simplifies the administration of EGWP and results in reduced cost for the plan sponsor, as it avoids the need to split the drug benefit between a Part D plan that does not cover brand drugs in the coverage gap and a wrap plan that does.8 Surveyed employers appear to be still favoring the EGWP + Wrap over this relatively newer enhanced EGWP approach, at least for the time being.9

The shift to EGWP+Wrap could bring savings to employers while largely preserving drug benefits for retirees.10 Because drug benefits can be preserved, the EGWP + Wrap approach could be appealing for both salaried and collectively bargained plans. Further, it may appeal to both public and private-sector employers as a strategy for reducing the retiree health obligations reported on their financial statements relative to the financial obligation reported under the RDS.

Private Exchanges for Medicare-Eligible Retirees

The strategy of transitioning from an employer-based retiree group health plan to using the non-group market for Medicare-eligible retirees is attracting interest among employers that offer retiree health benefits.11, 12 Employers adopting this strategy often engage a third party that provides an administrative coordinator or “exchange” platform that provides a variety of functions. This shift by employers to facilitate coverage for retirees through a private exchange is not new, though this approach has garnered a lot more attention in the media as more and more well-known companies have recently announced they are moving in this direction. Among the early adopters of this strategy were certain large U.S. manufacturers, e.g., automobile manufacturers Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors, which employed this strategy for their Medicare-eligible salaried former employees.

This private exchange strategy originated with Medicare-eligible retirees because of the widespread availability of traditional Medicare along with other options for Medicare-eligible retirees to obtain coverage as individuals, such as a combination of traditional Medicare plus Medigap, or a federally-funded Medicare managed care plan, or (since 2006) a Medicare Part D PDP. This strategy appeals to employers as a way of offering retirees a choice of health plans while controlling the employer’s future retiree health care costs and limiting their reported liabilities because of the shift to a defined contribution approach for funding these benefits and the consulting cost and administrative savings to the employer that may flow from the outsourcing to the private exchange.

Companies embarking on this approach typically use the third party coordinator or facilitator (the private exchange) to help retirees understand the choices available in the non-group market and facilitate the enrollment of the retiree in the plan of his/her choice. The exchange typically handles the administration, the billing and member services, with licensed benefit advisors, a call center, and online tools to assist retirees in plan selection. In many instances, the employer contributes a fixed defined contribution using a tax-effective health reimbursement arrangement (HRA) that is favorable for both the employer and the retiree and reimburses retirees for premiums and/or out-of-pocket expenses. The private exchange platform then helps apply that monetary contribution toward the individual retiree’s choices. According to a recent Aon Hewitt survey of employers, the revenue for the exchange platform mainly comes from the commission built into the health plan premiums.13

For retirees, the employer’s shift to a private exchange often means a wider range of plan choices for Medicare-eligible retirees along with decision support provided by the exchange. How the shift affects retirees’ costs will vary depending on the existing retiree health plan. On the one hand, premiums paid by retirees could be more attractive, especially in situations where retirees were expected to pay a large share of the premium or if the employer’s contribution to the retiree plan had been capped and the cap was hit or about to be hit, at which point any increases in retiree costs would be fully borne by the retiree. On the other hand, the defined contribution amount that the employer offers toward the exchange may or may not increase in line with medical inflation, if it increases at all, in which case retirees in the exchanges may be paying more than what they previously contributed. The hope is that the availability of multiple plan options will give retirees more flexibility in managing these costs by seeking lower-cost alternatives in the private exchange. In addition, private exchanges offer retirees access to benefits beyond just medical services, e.g., dental, vision, life, and other forms of voluntary insurance.

Two general types of private exchanges exist. The first is a multi-carrier model, where the exchange entity makes available to retirees a choice of health insurance options offered by multiple insurers. The second is a single-carrier model, where the medical plan options available are generally those offered by a single insurer. Thus far, employers tend to prefer the multi-carrier approach.

The number of private exchanges available to employers offering retiree health benefits is expanding, which may reflect growing interest among employers. By some tallies, there are now more than 100 private exchanges,14 though most of these are intended for active employees and not retiree populations The proliferation of these private exchanges and the different options for employers available through them has given rise to the Private Exchange Evaluation Collaborative — a joint effort among the Employers Health Coalition, the Midwest Business Group on Health, the Northeast Business Group on Health, the Pacific Business Group on Health, and PricewaterhouseCoopers — to create a comprehensive database of information that employers can use to analyze the various exchanges for active employees and retired groups.15 According to recent reports posted by the sponsors of these private exchanges for Medicare-eligible retirees:

- Towers Watson operates the largest private Medicare exchange, called OneExchange, serving more than 500,000 retirees16 after acquiring Extend Health in 2012. Towers Watson has more than 250 organizations as clients, and offers plan choices from more than 80 national/regional insurance carriers.

- Aon Hewitt operates a private exchange for Medicare-eligible retirees, called Aon Hewitt Navigators, which serves more than 300,000 Medicare-eligible retirees. It too describes on its website how it partners with over 80 leading insurance companies.17

- Mercer recently announced that 19 employers with a total of 35,000 retirees have chosen Mercer’s Medicare solution.18

- Buck Consultants, a Xerox Company, announced the launch of RightOpt®, a private health insurance exchange that includes a retiree exchange platform, My Medicare Advocate®, which serves 19 employers with 50,000 retirees.19

These private exchanges often provide more choices to retirees than would otherwise be offered under an employer-sponsored retiree health structure, but fewer plans than are currently offered to all Medicare beneficiaries in an area, outside the private exchange.20 The more narrow selection of available MA and PDP plans on private exchanges could be viewed as a positive by those who view the existing number of plans as overwhelming, but as a shortcoming to others for potentially not showing retirees that there may be some better plans out there. In addition, depending on the arrangement, the employer’s contribution to the health reimbursement account may sometimes only be available to the retiree for premium payments to plans that the retiree enrolls in through the private exchange, and not for use with other plans that the retiree may enroll in through the CMS site or directly with the insurers. The employer may want to ensure, for example, that the retiree receiving the employer-provided defined contribution has the benefit of the decision support tools and the full range of customer support for which the employer has contracted with the private exchange, rather than leaving the retiree to his/her own devices. The exchange may, for example, provide enrollees with advocacy services if the retiree later needs help with an insurance issue.

In addition to using private exchanges for Medicare-eligible retirees, some employers may ultimately envision going one step further, and paying an insurer to assume full responsibility for their retiree health obligations, thus eliminating the employer’s ongoing payments for these benefits which instead would get paid by the insurance company.21

The Current Policy Debate: Implications for Retiree Health

A number of proposals have been and are under discussion that could have important implications for employers that offer retiree health coverage and the retirees enrolled in them, including changes that would potentially impact the costs associated with coverage of both pre-65 and Medicare-eligible retirees. As noted earlier, the ACA includes a number of changes affecting employers and current and future retirees; thus, a significant change to the ACA (or outright repeal) could have far reaching effects; for example, outright repeal would, among other things, likely close the existing pathway to coverage for potentially millions of pre-65 retirees who are expected to eventually receive coverage through the federal/state marketplaces in the future.

Most of the other major policy proposals that would affect retiree health coverage are made within the context of changes to Medicare, so their most direct impact would be on retiree health benefits for Medicare-eligible retirees.

Medicare Proposals and Retiree Health

With ongoing concern about the rise in federal spending and concern about Medicare spending specifically, a number of proposals have been put forward to reduce Medicare spending that could have significant implications for beneficiaries with retiree health coverage, and for employers sponsoring retiree health plans. While such proposals are many and varied, this section highlights four general proposals that directly affect employer-sponsored retiree health plans.

Raising the Medicare Eligibility Age to 67

One proposal that has been consistently discussed over the years as a way of reducing spending is to gradually raise the Medicare eligibility age to 67. Under an option described by CBO, the Medicare eligibility age would increase by two months every year, beginning with beneficiaries born in 1951 (who will turn 65 in 2016), with projected net federal savings of $19 billion between 2014 and 2023.1

Beyond the effects on the federal budget, raising the Medicare age of eligibility would also have cost implications for beneficiaries, employers and other payers.2 Increasing the Medicare age would directly increase costs for retiree health plans, principally because the retiree health plan would be primary, rather than the secondary payer for two more years of retiree eligibility. In an earlier study, Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Actuarial Research Corporation (ARC) modeled the effects of raising the Medicare eligibility in a single year (2014), finding that employer retiree plan costs were estimated to increase by $4.5 billion in 2014 if the Medicare eligibility age is raised to 67.3 In addition, public and private employers offering retiree health benefits would be required to account for the higher costs in their financial statements as soon as the change is enacted. Employers would likely consider a variety of steps to lessen the added costs, which would likely mean higher out-of-pocket costs for these retirees. In addition, the loss of Medicare benefits for retirees ages 65 and 66 could make the federal/state marketplaces a more tempting employer strategy for their early retirees.

Changing Cost Sharing Under Medicare Part A and B

Medicare cost sharing changes could also have significant cost repercussions for some retiree health plans; but the amount of any increase and who bears the brunt of that cost will vary widely depending on the specific Medicare proposal – and there are many variations — the design of the retiree health plan (both the cost sharing provisions like deductibles and coinsurance and how the plan coordinates with Medicare) and the level and form of the employer contribution. In addition, retiree plans vary so widely that it will be hard for lawmakers to know in advance who exactly will be affected and how big the impact will be for specific groups. But in general, if the employer plan is going to cover the same things as it did before, and Medicare is now paying relatively less, the employer plan is going to pick up the difference. Beyond that, it gets complex and the impact varies with the proposal.

CBO described an option others have considered and endorsed that would have replaced the current benefit structure with a $550 combined Medicare Part A/B deductible, 20 percent coinsurance for nearly all services, and a $5,500 spending limit.4 CBO estimated that if those changes took effect on January 1, 2015, and the various dollar thresholds were indexed to average fee for-service Medicare costs per enrollee, that approach would reduce federal outlays by $52 billion between 2015 and 2023.5

As with other changes to Medicare, the benefit redesign could have implications for employers and other payers. According to a KFF/ARC analysis of the option described by CBO, total costs associated with employer-sponsored retiree coverage (employer and retiree share) would increase by $1.2 billion in 2013, and nine out of ten beneficiaries (87%) with retiree coverage would see an increase in out-of-pocket (cost-sharing and premium) spending in 2013.6 Even with a new $5,500 limit on out-of-pocket costs, employers’ costs would rise unless they reduced their wrap-around coverage because of other new cost-sharing requirements imposed on beneficiaries, such as an across-the-board 20 percent coinsurance on all Medicare-covered services. If the Medicare spending limit were set at $7,500 rather than $5,500, the total costs for retiree coverage would rise by more than three times as much, to an estimated $3.8 billion.7 If employers do not make conforming changes in their benefit design to limit their costs, they would be required to book the additional costs on their financial statements. Or, if a cap on the employer’s obligation is already in place, costs would be shifted to their retirees.

Imposing a Surcharge on Retiree Health Plan Coverage

Another proposal that emerged during recent debt reduction discussions would have imposed a surcharge on supplemental coverage, either Medicare supplemental insurance policies (Medigap) policies, employer-sponsored retiree health plans, or both.8,9 Sponsors of these proposals observe that individuals with first dollar or near first dollar coverage tend to use more Medicare-covered services, which in turn leads to higher Medicare spending. A premium surcharge would discourage individuals from obtaining supplemental coverage and/or indirectly recoup the additional costs to Medicare that result from such coverage.

A surcharge on employer-sponsored retiree health coverage may achieve savings for Medicare, but also raise costs for Medicare-eligible retirees who choose to retain their employer-sponsored benefits, assuming employers pass through the additional cost associated with the surcharge to their retirees. With a surcharge, retirees with lower incomes might be more inclined to forego supplemental coverage than higher income retirees, depending on the additional expense. Retirees who forego supplemental coverage as a result of the surcharge would save on premiums, but would potentially be exposed to higher costs for their medical care, and as a result, may forgo needed services due to costs. To the extent the proposal is limited to plans that provide first-dollar coverage, the proposal may have less of an impact on Medicare utilization and savings, or on retirees, in that employer-sponsored retiree plans do not generally provide first dollar coverage, in contrast to the most popular individual Medigap plans (C and F).10 A further consideration relates to administrative feasibility. Retiree health plan premiums vary by economic sector and by eligible retiree groups, e.g., grandfathered, current actives, new hires, salaried or bargained, and if bargained, which bargaining agreement. It is not unusual for the same large employer to sponsor multiple retiree plans, with different premium contribution requirements for different groups of retirees. For these reasons, proposals that impose a surcharge on supplemental coverage that is tied to the Medicare Part B premium, rather than the premium of a given retiree health plan, may be easier for Medicare to administer.

Prohibiting First Dollar Supplemental Coverage

As an alternative to a surcharge, some have proposed to establish requirements for supplemental coverage, for example, by prohibiting first-dollar coverage. Under this approach, future legislation could potentially limit the amount of the Medicare cost sharing that the retiree health plan could cover by mandating certain benefit design parameters of the employer sponsored plan, e.g., the retiree plan might be required to have at least a certain deductible, and/or the out-of-pocket spending limit could not be below a certain dollar amount.11

Such an approach would be a fundamental shift in policy, by stipulating the design of what are otherwise voluntary employer-provided retiree benefits and in some cases collectively bargained arrangements that cannot easily be altered. As CBO has noted, “regulations on retiree coverage would be more complex to administer than those on Medigap insurance.” 12

Conclusion

Retiree health strategies of employers are undergoing accelerated change, and several major trends in particular stand out for the future. A marked and growing interest in shifting to a defined contribution approach for both pre-65 and post-65 retiree coverage is fueled by the employers desire to manage future costs. Increasing interest in moving from group coverage to non-group coverage is a trend that is particularly strong with respect to Medicare-eligible retirees for whom employers can facilitate access to non-group coverage through private exchanges. And while the jury is still very much out, the new federal/state marketplaces are gaining at least the consideration by employers as a possible pathway through which the employer’s pre-65 retiree population might gain access to non-group coverage.

While eliminating retiree coverage is not the prevailing strategy expressed by employers, the number of employers offering retiree health coverage will continue to decline in the future as incremental numbers of employers may follow through on their interest in doing so as reported in surveys.

The pace of employer changes in strategy is very sensitive to changes in public policy, whether these would be as potential changes in the ACA or as potential reforms to Medicare. The immediate impact of any of the various proposals for Medicare redesign would depend on the nature of the proposals and on whether they would apply to current retirees or only to future retirees. If they would apply to future retirees, then potential budget savings would be lower; if they applied to current retirees, there would be more problems and disruption for retirees, and the flexibility for the employer plan may be limited, either by collective bargaining agreements, or by the state law for a public employer plan. Most private employers typically do reserve the right to change the health plans, but as a practical matter, in many cases they have been more reluctant to change the plans for current retirees than for recent or new retirees. In terms of future retirees, one would expect the employer plan to respond in ways that reflect the Medicare changes, including by making changes in the retiree plan design, or the employer contribution to the plan, or in the way the plan coordinates with Medicare, or adopt an approach that we have noted above is a growing trend, namely, providing the retiree with a defined contribution amount that the retiree can use to purchase an individual Medicare or Medigap plan, as opposed to the employer group plan.

Over the next few decades, these trends suggest that employer-sponsored supplemental coverage is likely to be structured differently and play a smaller macro role in retirement security than it has in the past and than it does today. Relatively fewer workers will have such coverage available in the future, to be sure. But for workers and current and future retirees who do have employer-sponsored retiree coverage, changes resulting from rising costs and/or shifts in public policy that could weaken the prospects of retirement security warrant close attention.

Endnotes

Introduction

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2010 Cost and Use File, and 2012 Current Population Survey.

Report

Overview of Health Benefits for Pre-65 and Medicare-Eligible Retirees

Paul Fronstin and Nevin Adams, “Employment-Based Retiree Health Benefits: Trends in Access and Coverage, 1997‒2010,” Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) Issue Brief, October 2012. http://www.ebri.org/pdf/briefspdf/EBRI_IB_10-2012_No377_RetHlth.pdf.

EBRI estimates 25 percent of the 8.5 million non-working retirees ages 45 to 64 had retiree health benefits, based analysis of the 2010 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP); this produces an estimated 2.1 million retirees. This number is similar to the number of 55 to 64-year old non-working retirees with retiree health benefits (2.4 million), based on the Kaiser Family Foundation’s analysis of the 2012 Current Population Survey (CPS). Neither the EBRI analysis nor the Kaiser Familiy Foundation analysis includes the spouses of retirees.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2008-2012 Current Population Survey.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey, August 2013. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/report/2013-employer-health-benefits/.

Mercer, Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, MTEBC, February 2013. http://benefitcommunications.com/upload/downloads/Mercer_Survey_2013.pdf.

Towers Watson, Reshaping Health Care: Best Performers Leading the Way, Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Employer Survey on Purchasing Value in Health Care, 2013. http://www.towerswatson.com/en-US/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2013/03/Towers-Watson-NBGH-Employer-Survey-on-Value-in-Purchasing-Health-Care.

Mercer, Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, MTEBC, February 2013. http://benefitcommunications.com/upload/downloads/Mercer_Survey_2013.pdf.

Fidelity Benefits Consulting, “Retiree health costs fall,” Fidelity Viewpoints, May 15, 2013. https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirees-medical-expenses. “Based on a hypothetical couple retiring at age 65 years or older, with average (82 male, 85 female) life expectancies. Estimates are calculated for ‘average’ retirees, but may be more or less depending on actual health status, area of residence, and longevity. Assumes individuals do not have employer-provided retiree health care coverage, but do qualify for Medicare. The calculation takes into account cost sharing provisions (such as deductibles and coinsurance) associated with Medicare Part A and Part B (inpatient and outpatient medical insurance). It also considers Medicare Part D (prescription drug coverage) premiums and out-of-pocket costs, as well as certain services excluded by Medicare. The estimate does not include other health-related expenses, such as over-the-counter medications, most dental services and long-term care.”

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2013 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, May 2013. http://downloads.cms.gov/files/TR2013.pdf.

Carlos Zarabozo and Scott Harrison, “Payment Policy and the Growth of Medicare Advantage,” Health Affairs, January 2009. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/28/1/w55.full.pdf+html.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2014. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Mar14_entirereport.pdf.

Non-group Medicare Advantage plans receive a percentage of the difference between the bid and the benchmark in the form of a rebate, and can use the rebate to provide extra benefits or lower cost-sharing to enrollees.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2014, Table 13-4. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Mar14_entirereport.pdf.

Marsha Gold, Gretchen Jacobson, Anthony Damico, and Tricia Neuman, “Medicare Advantage 2013 Spotlight: Enrollment Market Update,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2013. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2013-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/.

Gretchen Jacobson, “Medicare and the Federal Budget: Comparison of Medicare Provisions in Recent Federal Debt and Deficit Reduction Proposals,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2014. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-and-the-federal-budget-comparison-of-medicare-provisions-in-recent-federal-debt-and-deficit-reduction-proposals/.

Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2014 Budget of the U.S. Government, April 10, 2013.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2014/assets/budget.pdf. For the FY 2015 proposal, see http://www.hhs.gov/budget/fy2015/fy-2015-budget-in-brief.pdf.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicare Program; Contract Year 2015 Policy and Technical Changes to the Medicare Advantage and the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Programs,” Federal Register, Vol. 79, No. 7, January 10, 2014. https://federalregister.gov/a/2013-31497.

Mercer, Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, MTEBC, February 2013. http://benefitcommunications.com/upload/downloads/Mercer_Survey_2013.pdf.