Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities and Medicare

Access to Care and Service Utilization

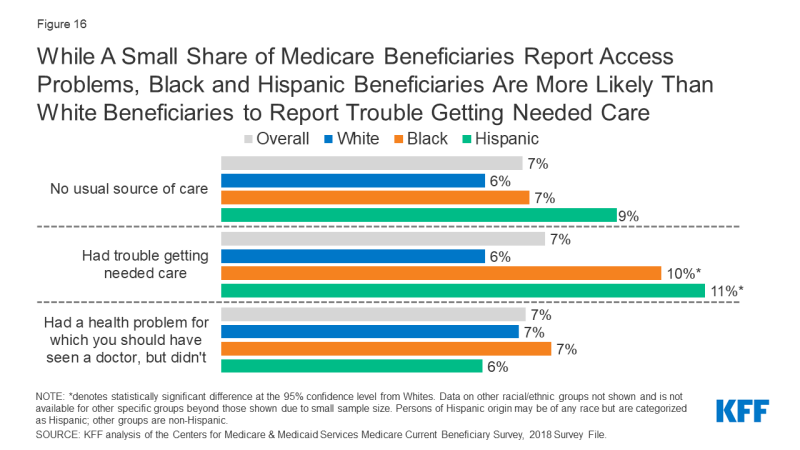

While a Small Share of Medicare Beneficiaries Overall Report Access Problems, Black and Hispanic Beneficiaries are More Likely than White Beneficiaries to Report Trouble Getting Needed Care

Overall, relatively few Medicare beneficiaries report problems with access to care, with no significant differences across racial and ethnic groups in the share of beneficiaries without a usual source of care or in the share of beneficiaries delaying needed care. These findings illustrate the importance of health insurance coverage in ensuring access to care and mitigating racial and ethnic disparities in some measures of access.

However, a larger share of Black (10%) and Hispanic (11%) beneficiaries than White beneficiaries (6%) report trouble getting needed care (Figure 16). Recent analysis by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) found that in 2019, among Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older, people of color were more likely than White beneficiaries to report unwanted delays in getting an appointment and problems finding a new specialist. This pattern was also observed among privately insured adults ages 50-64.

Figure 16: While A Small Share of Medicare Beneficiaries Report Access Problems, Black and Hispanic Beneficiaries Are More Likely Than White Beneficiaries to Report Trouble Getting Needed Care

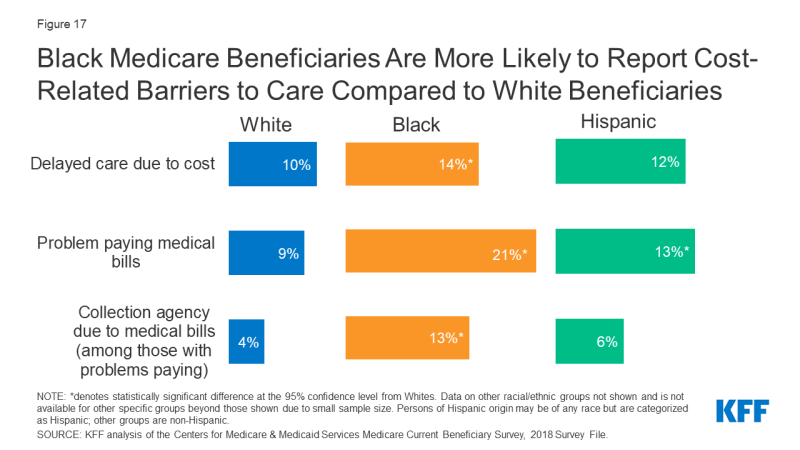

Black Medicare Beneficiaries Are More Likely to Report Cost-Related Barriers to Care Compared to White Beneficiaries

A larger share of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries than White beneficiaries report problems paying medical bills (21%, 13%, and 9%, respectively) and delaying care due to cost (14%, 12%, and 10% respectively). Among those with problems paying medical bills, a larger share of Black beneficiaries report debt to collection agencies due to medical bills than White beneficiaries (13% versus 4%, respectively) (Figure 17).

Figure 17: Black Medicare Beneficiaries Are More Likely to Report Cost-Related Barriers to Care Compared to White Beneficiaries

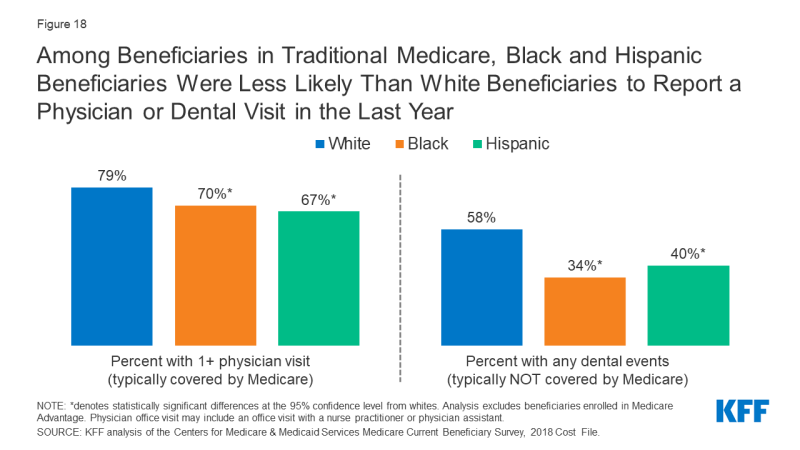

Among Beneficiaries in Traditional Medicare, Black and Hispanic Beneficiaries Were Less Likely Than White Beneficiaries to Report a Physician or Dental Visit in the Last Year

The majority of all beneficiaries in traditional Medicare saw at least one physician in 2018. However, the rate was lower among Black and Hispanic beneficiaries than among White beneficiaries (70% and 67%, respectively, compared to 79%). (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Among Beneficiaries in Traditional Medicare, Black and Hispanic Beneficiaries Were Less Likely Than White Beneficiaries to Report a Physician or Dental Visit in the Last Year

While traditional Medicare provides coverage for an array of medical services, it does not cover routine dental care. Consequently, in 2018, just over half (54%) of the Medicare population saw a dentist in the past year, with lower rates among Black beneficiaries (34%) and Hispanic beneficiaries (40%) than among White beneficiaries (58%) (Table 5).

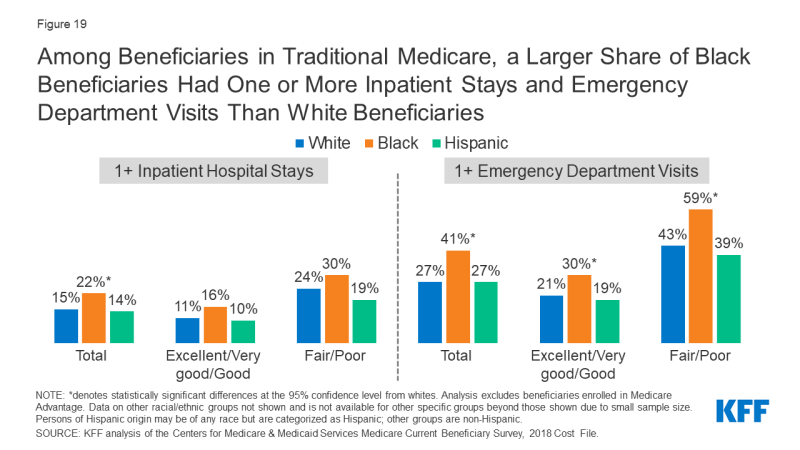

Among Beneficiaries in Traditional Medicare, a Larger Share of Black Beneficiaries Had One or More Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits Than White Beneficiaries

Among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, a larger share of Black beneficiaries had an inpatient hospital stay than White beneficiaries (22% versus 15%, respectively) (Figure 19). The share of beneficiaries reporting at least two inpatient stays was also higher among Black beneficiaries (7%) than among White beneficiaries (4%) (Table 5). Racial/ethnic differences in inpatient stays (1+ days and 2+ days) did not differ significantly by self-reported health status.

Figure 19: Among Beneficiaries in Traditional Medicare, a Larger Share of Black Beneficiaries Had One or More Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits Than White Beneficiaries

A larger share of Black beneficiaries had one or more emergency department (ED) visits compared to White beneficiaries (41% versus 27%, respectively). In contrast to inpatient hospital stays, racial differences in ED visit rates by self-reported health status were observed. Specifically, Black beneficiaries in fair/poor health status were more likely than White beneficiaries of similar health status to report any emergency department visit (59% versus 43%, respectively). But even among Medicare beneficiaries in relatively better health (defined as excellent, very good, or good self-reported health status), Black beneficiaries were more likely than White beneficiaries to have an emergency department visit (30% vs. 21%, respectively). Additionally, the share of Black beneficiaries with two or more ED visits (24%) was twice as large as the share among White beneficiaries (12%).

Emergency Department Visit Rates for Hypertension, Diabetes, Stroke, and Heart Failure were Higher among Black Medicare Beneficiaries than Beneficiaries in Other Racial and Ethnic Groups

Among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with hypertension, the rate of ED visits among Black beneficiaries (53 per 1,000 people) was at least double the rates among White and Asian beneficiaries (22 and 21 visits per 1,000 people, respectively) and nearly double the rates among Hispanic and American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries (Figure 20). Among beneficiaries diagnosed with diabetes, ED visit rates among Black, Hispanic, and American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries (22, 17, and 20 visits per 1,000 beneficiaries, respectively) were at least double the rates among White and Asian beneficiaries (8 visits per 1,000 beneficiaries). Asian and Pacific Islander beneficiaries had lower ED visit rates for hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and heart failure compared to beneficiaries in other racial and ethnic groups.

Hospital Readmission Rates are Higher among Black Medicare Beneficiaries than Beneficiaries in Other Racial and Ethnic Groups

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), which has been in place since 2012, aims to reduce avoidable hospital readmission rates and improve quality of care by imposing payment penalties on hospitals with excess readmission rates for certain health conditions. In 2018, 30-day readmission rates among Medicare beneficiaries in traditional Medicare were higher among Black beneficiaries (19%) than among White beneficiaries (14%), Hispanic beneficiaries (17%), Asian/Pacific Islander beneficiaries (14%), and American Indian/Alaska Native beneficiaries (16%) (Figure 21). Black beneficiaries had higher odds of being readmitted to a hospital than White beneficiaries, regardless of diagnosis during the first hospitalization or discharge setting.

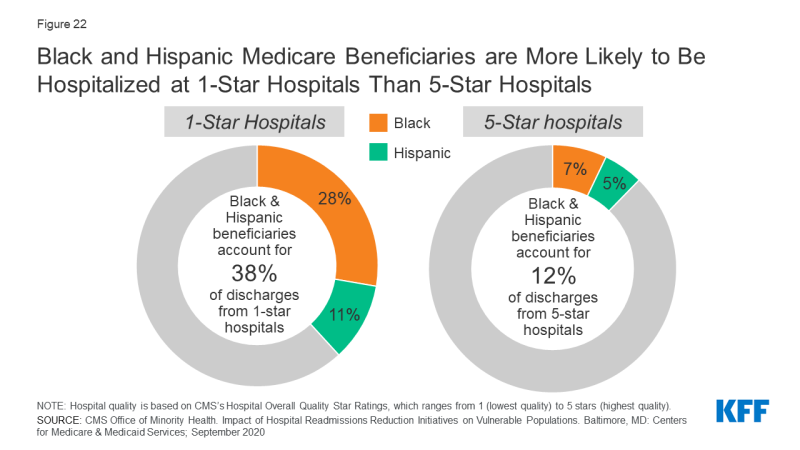

Black and Hispanic Medicare Beneficiaries are More Likely to be Hospitalized at 1-Star Hospitals than 5-Star Hospitals

CMS’s overall hospital quality star rating summarizes hospital performance on various measures, such as rates of readmissions, healthcare-associated infections, and value of care for certain health conditions (e.g., pneumonia) into a single star rating for each hospital, which ranges from 1 star (lowest quality) to 5 stars (highest quality). In 2018, Black and Hispanic beneficiaries accounted for 28% and 11% of discharges from 1-star hospitals, respectively, but only 7% and 5% of discharges from 5-star hospitals, respectively (Figure 22).

Figure 22: Black and Hispanic Medicare Beneficiaries are More Likely to Be Hospitalized at 1-Star Hospitals Than 5-Star Hospitals

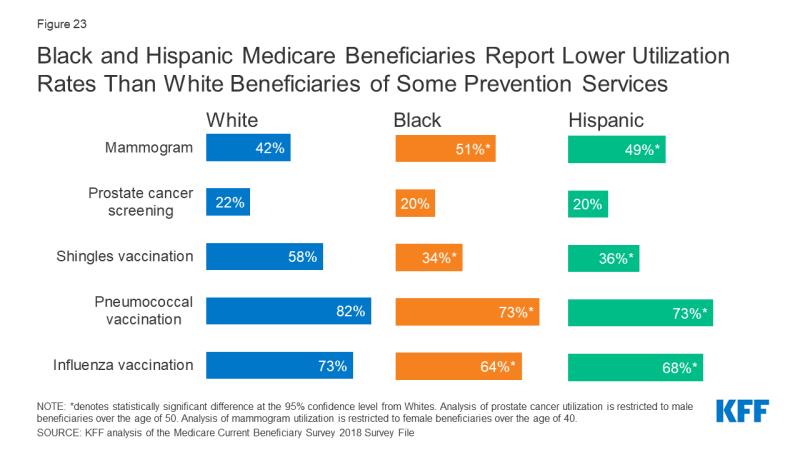

Black and Hispanic Beneficiaries Report Lower Utilization Rates Than White Beneficiaries of Some Prevention Services

Medicare provides coverage for a wide range of preventive and screening services, including a “Welcome to Medicare” physical exam during the first year of Medicare enrollment, immunization for various conditions (including influenza), and screening exams for cancers.

Overall, less than a quarter (21%) of male beneficiaries ages 50 and older reported receiving a prostate cancer screening, with no statistically significant differences by race or ethnicity (Figure 23). Less than half (43%) of all female beneficiaries ages 40 and older reported receiving a mammogram in the past year, with Black and Hispanic beneficiaries being more likely than White beneficiaries to receive a mammogram in the past year (51%, 49%, 42%, respectively).

Figure 23: Black and Hispanic Medicare Beneficiaries Report Lower Utilization Rates Than White Beneficiaries of Some Prevention Services

Notable racial and ethnic disparities in immunization rates were also observed among Medicare beneficiaries. Smaller shares of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries reported receiving a flu vaccination than White beneficiaries (64%, 68%, and 73%, respectively). Research has shown that the gap in flu vaccination is even greater when it comes to receipt of high-dose influenza vaccine,1 which is specifically targeted to adults ages 65 and older. Additionally, compared to White beneficiaries, Black and Hispanic beneficiaries had lower rates of pneumococcal vaccination and shingles vaccination. Several potential factors may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in vaccination uptake, including, but not limited to, differential access to and use of preventive health care services, concerns or misconceptions about vaccine safety, and persistent medical mistrust rooted in a history of racial discrimination and mistreatment in the health care sector.