Options to Make Medicare More Affordable For Beneficiaries Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

Key Findings

To date, the federal government has taken several steps to address the health and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, including sending billions of dollars to hospitals and other providers, providing economic stimulus payments to a majority of Americans, and requiring public and private insurers to provide free coverage of coronavirus testing. But the pandemic has exposed long-standing gaps in the U.S. health care system and brought fresh reminders of the health care affordability challenges facing many people, with and without insurance, including people with Medicare.

Medicare provides significant health and financial protections to more than 60 million Americans, but there are gaps in coverage and high cost-sharing requirements that can make health care difficult to afford, particularly for beneficiaries with modest incomes who lack supplemental coverage, such as employer-sponsored retiree health coverage, Medigap, or Medicaid. Beneficiaries are responsible for Medicare’s premiums, deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements, unless they have supplemental coverage or have incomes and assets low enough to qualify for the Medicare Savings Programs, which help cover Medicare Part A and Part B out-of-pocket costs, or the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) program, which helps with Part D premiums and cost sharing only.

Beneficiaries in traditional Medicare with no supplemental coverage are vulnerable to high out-of-pocket expenses because Medicare, unlike marketplace and large employer plans, has no cap on out-of-pocket spending for covered services. But even those with supplemental coverage can face affordability challenges. Although Medicare Advantage plans are required to provide an annual out-of-pocket limit, beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans could still face high out-of-pocket costs, depending on the services they use, the drugs they take, and costs charged by their specific plan. And although beneficiaries with Medigap supplemental coverage have help with cost-sharing requirements for Medicare-covered services and protection against catastrophic expenses, premiums for these policies can be costly. With half of all Medicare beneficiaries living on an income of less than $30,000 per person, these affordability concerns could be compounded for some by the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This report analyzes several policy options that could help make health care more affordable for people covered by Medicare:

- Add an out-of-pocket limit to Medicare Part A and Part B.

- Add a hard cap on out-of-pocket drug spending under Medicare Part D.

- Expand Medicare premium and cost-sharing assistance to low-income Medicare beneficiaries through the Medicare Savings Programs.

- Expand Part D premium and cost-sharing assistance to low-income Medicare beneficiaries through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program.

For each of the options, we discuss implications and tradeoffs, including the added cost to the federal government of providing additional protection for beneficiaries. This report focuses on options to improve affordability of current Medicare benefits, rather than options that would expand the benefits Medicare covers, such as adding coverage of dental, vision, or hearing services. See Methodology for detail on data sources and methods.

Key Takeaways

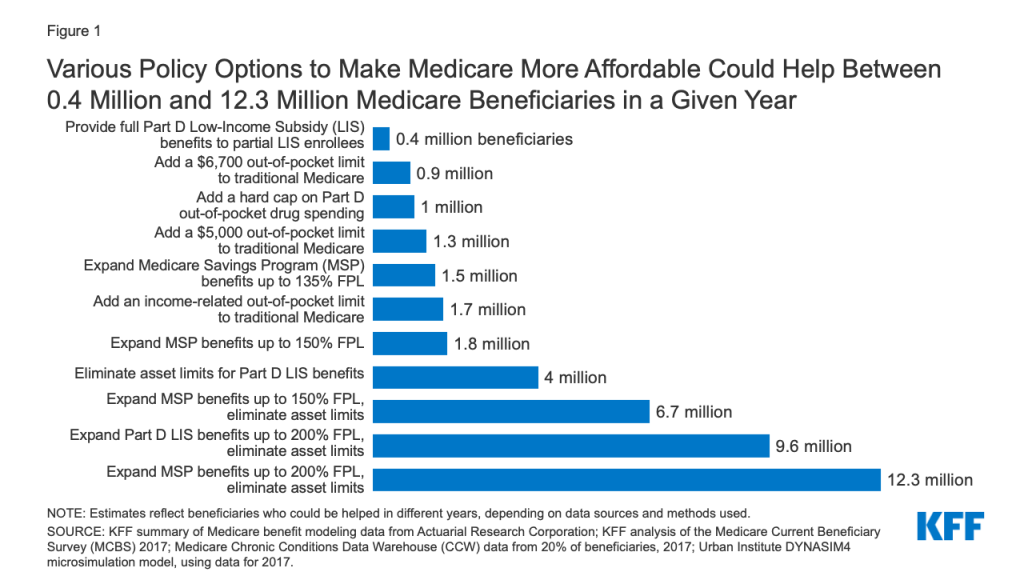

The policy options examined in this analysis to help make health care more affordable for people covered by Medicare vary in the number of beneficiaries who could be helped and how much help they could receive (Figure 1). Each option would also have cost implications for Medicare and/or other payers, as described more fully in the longer discussion of each option following the introduction.

- Adding an annual out-of-pocket spending limit to traditional Medicare for Medicare Part A and B cost-sharing requirements would limit the risk of incurring high and potentially unaffordable expenses for nearly six million beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who have no supplemental coverage. The number of beneficiaries likely to be helped in any given year, and the average savings per beneficiary reaching the limit, would vary based on the amount of the out-of-pocket limit and what counts toward the limit. For example, adding a $6,700 out-of-pocket limit to Medicare Parts A and B would help 0.9 million beneficiaries in 2021, reducing their out-of-pocket costs for Medicare-covered services by approximately $2,700, on average, while adding an income-related limit would help 1.7 million beneficiaries, with average savings of nearly $2,200 in 2021. Adding an out-of-pocket limit would help people on Medicare with complex care needs, such as those who require one or more inpatient stays followed by a lengthy stay in a skilled nursing facility, or those who need high-cost medications that are covered under Medicare Part B. Adding an out-of-pocket limit to traditional Medicare would also lower Medigap premiums and premiums for employer or union-sponsored retiree health benefits for Medicare-eligible retirees, because the new out-of-pocket limit in traditional Medicare would reduce the amount of claims to be paid by these payers, while at the same time increasing Medicare Part B premiums, as Medicare assumes these costs above the limit.

- Adding a hard cap on out-of-pocket prescription drug spending to the Part D benefit would eliminate potential exposure to high drug costs for nearly 39 million beneficiaries currently enrolled in Part D plans who are not receiving low-income subsidies. Had the Part D benefit included a cap in 2017, with no other changes in benefit design, it would have lowered out-of-pocket drug spending for approximately 1 million Part D enrollees with high drug costs, with average savings of approximately $1,400 per enrollee that year.

- Expanding eligibility under the Medicare Savings Programs would help more low- and modest-income beneficiaries with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing requirements, with the number helped and the amount of assistance varying depending on the option. For example, expanding financial assistance under the Medicare Savings Programs by covering cost sharing for people currently receiving Part B premium assistance only would lower out-of-pocket costs for 1.5 million Medicare beneficiaries, with estimated average savings of $1,500 in 2020. Raising eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs up to 150% or 200% of poverty and eliminating the asset test could help 7 million beneficiaries in total (expanding eligibility up to 150%) or 12.3 million beneficiaries (expanding eligibility up to 200%). Among these newly-eligible beneficiaries, estimated average savings would be $3,235 in 2020 for those who qualified for assistance with both premiums and cost sharing. For beneficiaries with incomes at 150% of poverty in 2020 ($19,140), this total savings represents 17% of their incomes. The group of beneficiaries who are helped under an approach that expanded eligibility up to 200% FPL with no asset test includes an estimated 3.9 million beneficiaries in communities of color, including 1.2 million Black beneficiaries, 1.9 million Hispanic beneficiaries, and 0.7 million beneficiaries in other racial and ethnic groups.

- Expanding eligibility under the Part D Low-Income Subsidy program would help more low and modest income beneficiaries with their Part D prescription drug plan premiums and cost-sharing requirements, with the number helped and the amount of assistance varying depending on the option. For example, providing full Part D low-income subsidies to beneficiaries who would otherwise be eligible for partial subsidies would lower prescription drug-related costs for 0.4 million Medicare beneficiaries, with estimated saving ranging from $270 to $560 in 2020, depending on the level of help they are eligible for under current law. Raising eligibility for Part D premium and cost-sharing subsidies from 150% FPL to 200% FPL, and eliminating the asset test would lower prescription drug-related costs for 9.6 million Medicare beneficiaries. Part D enrollees who are not currently eligible for premium or cost-sharing assistance would see estimated savings of $850 in 2020 on their Part D prescription drug cost sharing and premiums, on average, if they qualified for full LIS benefits.

As noted above, each of these options would also have cost implications for Medicare that would vary depending upon specific policy features. In addition, some of these options would have spillover effects for other payers (Medicaid, employers and unions). These effects are discussed more fully below.

Report

Introduction

Medicare plays a primary role in providing health care to more than 60 million older adults and younger adults with disabilities, but many people on Medicare still struggle with high out-of-pocket health care costs. Medicare provides protection against the costs of many health care services, but traditional Medicare has relatively high deductibles and cost-sharing requirements and places no limit on beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket spending for services covered under Parts A and B. In addition, for beneficiaries in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, there is no hard cap on out-of-pocket spending under the Part D prescription drug benefit.

In light of Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements and lack of an annual out-of-pocket spending limit, beneficiaries in traditional Medicare with no supplemental coverage are vulnerable to high out-of-pocket expenses. But even those with supplemental coverage may face health care affordability challenges. Although Medicare Advantage plans are required to provide an annual out-of-pocket limit, beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans could still face high out-of-pocket costs, depending on the services they use, the drugs they take, and costs charged by their specific plan. And although beneficiaries with Medigap supplemental coverage have help with cost-sharing requirements for Medicare-covered services and protection against catastrophic expenses, premiums for these policies can be costly.

The burden of out-of-pocket spending among Medicare beneficiaries is significant. The average person with Medicare coverage spent $5,460 out of their own pocket for health care, including premiums and service-related costs, in 2016. One in six Medicare beneficiaries reported problems getting care or delayed care due to cost, or had problems paying medical bills in 2017, with higher rates reported among beneficiaries in fair or poor health, those with low incomes, and those without supplemental coverage. Out-of-pocket spending on health care costs consumes a large share of individual Social Security income – 41% on average in 2013 – and is projected to consume a growing share of income for older adults over time. The economic downturn brought about by the pandemic, resulting in job losses and involuntary retirement among older adults, coupled with rising health care costs, could strain financial resources among some older adults for years to come, posing a threat to retirement security.

Although paying for health care costs can be burdensome for people with Medicare, beneficiaries with low incomes can get help paying their Medicare Part A and Part B premiums and cost-sharing expenses from Medicaid through the Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs), and Part D premiums and cost sharing from Medicare through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program. Most, but not all beneficiaries who get help through the Medicare Savings Programs are also eligible for full Medicaid benefits, which can include long-term care services, and often other services such as dental and vision.

Although difficult to measure precisely due to data limitations, we estimate that the share of Medicare beneficiaries with incomes below 150% FPL who are enrolled in the Medicare Savings Programs is somewhere between 50% and 65%, and 55% to 70% are enrolled in the Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program (although not everyone with incomes at this level are eligible to begin with due to the asset tests in both programs).1 Eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs and the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy program is generally stricter than coverage under Medicaid in states that elected to expand Medicaid under the ACA, and stricter than eligibility for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reduction subsidies in the ACA marketplace. Both the Medicare Savings Programs and Part D LIS impose an asset test, in addition to an income test.

Many low-income Medicare beneficiaries do not qualify for the MSPs or LIS, either because of assets above allowable limits or income that, while still low, is just above current thresholds. For example, nearly one million beneficiaries with incomes less than 150% FPL had assets above the highest allowable limit for LIS in 2017 ($12,320 for individuals/$24,600 for couples) but less than $30,000 in assets in 2017.2 Furthermore, certain groups of beneficiaries are less likely than others to be receiving assistance from the Medicare Savings Programs, which could expose them to higher health care costs. For example, nearly one in five Black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries (18%, respectively) have incomes below 150% of poverty but are not enrolled in the Medicare Savings Programs, compared to 14% of White beneficiaries.3 Similarly, 17% of beneficiaries ages 85 and older and 16% of beneficiaries ages 74 to 85 have incomes below 150% of poverty and are not enrolled in these programs, compared to 14% of beneficiaries ages 65 to 74.4

In the midst of the health and economic crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, and in light of the gaps in Medicare’s financial protections and in existing financial assistance programs available to low-income beneficiaries, there are several options policymakers could consider that would help to ease the financial burden on lower-income Medicare beneficiaries and those who are exposed to high out-of-pocket costs. This brief analyzes four policy options, and provides estimates of the potential number of beneficiaries who could be helped by each policy option. It also examines the potential out-of-pocket savings for beneficiaries for each option, and possible budgetary effects for federal and state governments. (See Methodology for details on the data and methods used in this analysis.)

The four policy options are:

- Add an annual out-of-pocket spending limit to traditional Medicare for services covered under Part A and Part B.

- Establish a hard cap on annual out-of-pocket drug spending in the Part D prescription drug benefit (with no additional changes to the Part D benefit design).

- Expand financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs to beneficiaries now eligible for premium assistance only, and expand eligibility for premium and cost-sharing assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs to more low-income beneficiaries (with no changes to eligibility for full Medicaid benefits, such as long-term services and supports).

- Expand financial assistance through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy program to beneficiaries now eligible for partial premium and cost-sharing assistance, and expand eligibility for the Low-Income Subsidy program to more low-income beneficiaries.

(back to top).

Options to Improve Medicare’s Financial Protections

Add an Out-of-Pocket Limit to Traditional Medicare

Traditional Medicare currently places no limit on the out-of-pocket costs that beneficiaries are required to pay each year for services covered under Part A (hospital insurance) and Part B (supplementary medical insurance). This gap in Medicare’s financial protection is a relic from an earlier era, and makes coverage under traditional Medicare unlike Medicare Advantage plans and private coverage offered by employers or in the ACA marketplace, where annual out-of-pocket limits are generally required by law.

Most beneficiaries in traditional Medicare have supplemental coverage that helps cover cost-sharing requirements, such as the Medicare Savings Programs, employer or union-sponsored retiree health benefits, and Medigap policies. In addition, beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans in 2020 have the protection of an out-of-pocket limit for services covered under Medicare Parts A and B, not to exceed $6,700 for in-network services, and $10,000 for services provided out-of-network. But premiums for retiree health and Medigap supplemental coverage can be expensive, and not all beneficiaries want to accept the network restrictions that come with enrolling in a Medicare Advantage plan in order to get an out-of-pocket spending cap.

The nearly six million beneficiaries who do not have supplemental coverage can face significant expenses for medical care if they get sick – including a $1,408 hospital deductible in 2020, daily costs for extended stays in a hospital or skilled nursing facility, and 20% coinsurance for high-cost physician-administered drugs, such as chemotherapy drugs. These costs can be a particular concern for beneficiaries with modest incomes with no supplemental coverage. Nearly 4 in 10 (39%) beneficiaries in traditional Medicare with no supplemental coverage have incomes less than $20,000 a year, nearly 3 in 10 (29%) are in fair or poor health, nearly a quarter (23%) are people of color, and 15% are age 85 or older.

Using a model developed in consultation with the Actuarial Research Corporation, we examined three options for adding an out-of-pocket limit to traditional Medicare, with no other changes in deductibles or cost-sharing requirements:

- A uniform $5,000 out-of-pocket spending limit.

- A uniform $6,700 out-of-pocket spending limit.

- An income-related out-of-pocket spending limit, beginning at $3,350 for beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% of poverty and scaling up to $9,500 for beneficiaries with incomes above 1,000% of poverty (no asset test would apply).

Below we provide estimates of the number of people who could be helped under these different options and estimated budgetary effects in terms of both out-of-pocket spending, and federal and state government spending. The estimates we present below assume the out-of-pocket spending limit would apply to beneficiaries’ own out-of-pocket spending and to spending paid by Medicaid on behalf of dually-eligible beneficiaries. Payments made by employer and union-sponsored plans for deductibles and cost-sharing requirements on behalf of retirees and payments from Medigap insurers would not count toward the out-of-pocket spending limit.

Beneficiary Effects

Adding an out-of-pocket spending limit to Medicare would help the relatively small number of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare with exceedingly high medical costs in any given year, but disproportionately benefit those with serious illnesses who do not have supplemental coverage, including beneficiaries who take high-cost Part B drugs for cancer or other diseases, beneficiaries with one or more inpatient hospital admission, and those who have extended stays in a skilled nursing facility, including beneficiaries with SARS-CoV-2 who account for a disproportionate share of people in the U.S. hospitalized with COVID-19.

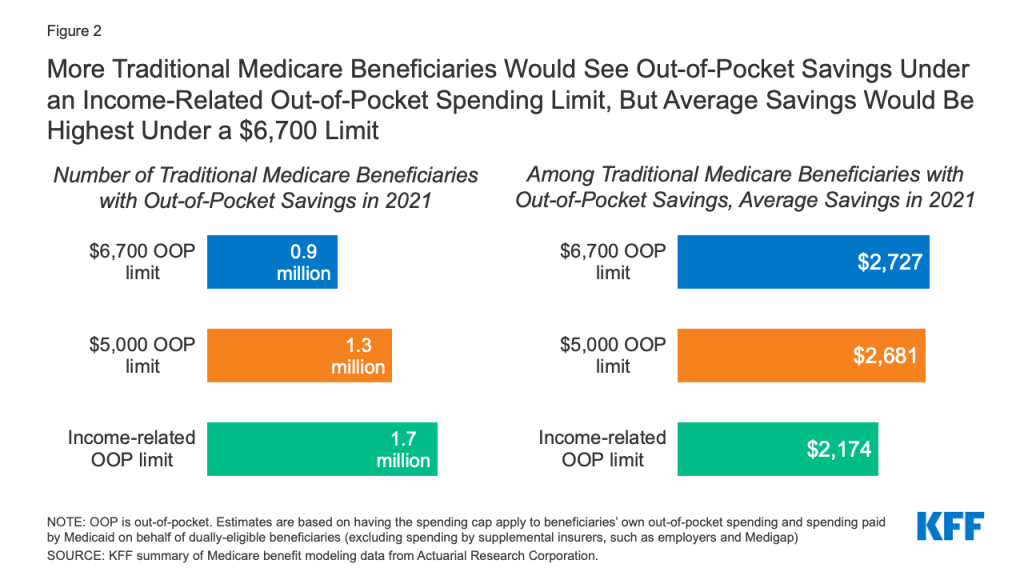

Based on the three out-of-pocket spending limits we evaluated, the estimated number of traditional Medicare beneficiaries who could see lower out-of-pocket health care costs if this proposal were implemented in 2021 would range from 0.9 million to 1.7 million (Figure 2):

- 0.9 million Medicare beneficiaries would benefit from a $6,700 limit on out-of-pocket spending in 2021, or 2% of all traditional Medicare beneficiaries overall, reducing their out-of-pocket spending on Medicare-covered services by more than $2,700.

- 1.3 million Medicare beneficiaries would benefit from a $5,000 limit on out-of-pocket spending in 2021 (3% of all traditional Medicare beneficiaries), reducing their out-of-pocket spending on Medicare-covered services by just under $2,700.5

- 1.7 million Medicare beneficiaries would benefit from an income-related spending limit (4% of all traditional Medicare beneficiaries), reducing their out-of-pocket spending on Medicare-covered services by $2,200.

The estimated number of people expected to benefit directly from a limit on out-of-pocket spending in a given year is highest under the income-related limit because this option provides a lower limit of $3,350 for beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% of poverty than the limit for beneficiaries with higher incomes. Since many Medicare beneficiaries have relatively low incomes, more beneficiaries would have spending that reaches this lower spending limit, than with a uniform $5,000 or $6,700 spending limit that applies to all beneficiaries. Among these three options, fewer beneficiaries would have spending high enough to reach a uniform $5,000 limit than under the income-related approach, and fewer still would have spending high enough to reach the $6,700 limit.

Beneficiaries with higher levels of utilization would be expected to save more than the average under each option, such as Medicare beneficiaries with two or more hospital stays and those who are hospitalized and then have a skilled nursing facility stay. For example, under the $6,700 spending limit, 0.3 million Medicare beneficiaries with two hospital stays would experience a $3,500 reduction in out-of-pocket costs in 2021, and 0.2 million beneficiaries who are hospitalized and have a lengthy skilled nursing facility stay would see a $4,100 reduction in out-of-pocket costs.

Although the number of beneficiaries helped by an annual out-of-pocket limit in any given year may be relatively small, an annual out-of-pocket limit would help a larger number of beneficiaries over a longer timeframe of multiple years. For example, a prior analysis conducted by ARC for KFF and MedPAC found that the share of traditional Medicare beneficiaries with cost-sharing liability above an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $5,000 for one or more years would increase from 6-7% in the first year to 19% after five years and 32% over 10 years. In other words, over 10 years, nearly one-third of Medicare beneficiaries would have annual cost-sharing liability above the annual out-of-pocket limit in one or more years over that time period.

Having a spending cap in traditional Medicare would provide beneficiaries with the peace of mind that comes from knowing they would not be responsible for thousands of dollars in liability if they incur high medical costs at some point in the future. However, under each of these options, most beneficiaries in traditional Medicare would see no change in their out-of-pocket costs for Medicare-covered services in a given year, since they would not have spending high enough to reach the limit; however their Part B premiums would be expected to increase modestly, due to an overall increase in Part B spending.

The addition of a spending limit to traditional Medicare could mean fewer beneficiaries enroll in Medicare Advantage to obtain the protection of the out-of-pocket cap. It could also mean fewer people choose Medigap to supplement traditional Medicare, generating savings on Medigap premiums for those who drop their policies, which could amount to more than $2,000 in savings in a given year.6 Beneficiaries who choose to keep Medigap even with an out-of-pocket limit in traditional Medicare could see a reduction in their premiums, because Medigap insurers would not be liable for costs that enrollees incur above the new limit. With savings from a reduction in claims associated with spending above the new out-of-pocket limit, Medigap insurers could pass savings on to policyholders in the form of lower premiums to meet loss ratio requirements. Similarly, employers and unions that continue to sponsor retiree health benefits for Medicare-eligible retirees would likely realize savings associated with a Medicare out-of-pocket spending limit, which could lead to a reduction in plan costs for sponsors (employers and unions) and a reduction in premiums for retirees.

Budget Effects

According to model estimates, the net one-year federal cost of adding an out-of-pocket spending limit to traditional Medicare in 2021 would range from approximately $11 billion under the $6,700 limit to $15 billion under the $5,000 limit and $16 billion under the income-related limit. These estimates are based on the spending limit applying to beneficiaries’ own out-of-pocket spending plus Medicaid cost-sharing payments on behalf of dually-eligible beneficiaries. But the federal budget effects under each spending limit would be lower if the spending limit applied only to beneficiaries’ own out-of-pocket spending, and higher if the limit applied to spending by all payers, including beneficiaries, Medicaid, and supplemental insurers such as employers and Medigap. The net federal cost increases as more payer spending counts towards the limit because a larger number of beneficiaries would reach the spending limit and Medicare would assume liability for more beneficiaries’ costs above the limit, displacing spending by Medicaid and supplemental insurers (Table 1).

For example, under the $6,700 spending limit, net federal spending in 2021 would increase by $5.4 billion if the spending limit applies to beneficiary out-of-pocket costs only; $10.9 billion if the limit applies to beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs and payments made on their behalf by Medicaid; and $18.6 billion if the limit applies to spending by beneficiaries, Medicaid, and supplemental insurers, including employer-sponsored retiree plans and Medigap. Under the income-related spending limit, net federal spending in 2021 would increase by $8.2 billion if the spending limit applies to beneficiary out-of-pocket costs only; $16.2 billion if the limit applies to beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs and payments made on their behalf by Medicaid; and $24.7 billion if the limit applies to spending by beneficiaries, Medicaid, and supplemental insurers, including employer-sponsored retiree plans and Medigap. Net federal spending effects for the $5,000 limit are similar to the income-related limit.

These Medicare spending estimates factor in higher Medicare payments to Medicare Advantage plans, which would result from adding an out-of-pocket spending limit to traditional Medicare (a benefit that Medicare Advantage plans are currently required to provide). This is because, in the absence of changes to how Medicare Advantage benchmarks are calculated (an amount used in determining how plans are paid), the new spending limit would increase per capita costs in traditional Medicare, leading to higher benchmarks, which would in turn likely lead to higher Medicare Advantage plan bids and higher payments to plans.

Other payers. Having the spending limit apply to Medicaid cost-sharing payments for dually-eligible beneficiaries would reduce state Medicaid liability by between $2 billion and $3 billion in one year alone (2021), depending on the spending limit, which could be an important consideration at a time when state budgets have been decimated by tax revenue losses resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

If, however, the spending limit applied to payments by supplemental payers such as employers and unions on behalf of retirees, it would result in savings for those payers (although we did not model these estimates) and significantly higher costs for Medicare Even if the Medicare limit did not count spending by employer/union plans on behalf of retirees, employers/unions could realize savings if they modify their benefits to limit their own liability. There is some risk that the added protection in Medicare would accelerate the erosion of retiree health benefits.

A new out-of-pocket limit for traditional Medicare could also have spillover effects for Medigap policyholders and insurers. If Medigap policyholders decide to drop their policies due to the added protection of an out-of-pocket limit under Medicare, they would incur higher costs for Medicare-covered services (while also seeing lower premiums), which could lead to lower utilization of these services as well as lower and Medicare spending. The reduction in spending for Medicare-covered services due to lower utilization could partially offset additional costs to the federal government associated with adding an out-of-pocket limit. We did not incorporate any such potential changes in the model. If, instead, beneficiaries choose to retain their Medigap policies, they would likely see a reduction in premiums, as noted above (See our previous analyses of Medicare benefit redesign options for more discussion of possible behavioral responses by individuals and other payers to an out-of-pocket limit.)

Establish a Hard Cap on Out-of-Pocket Spending In Medicare Part D

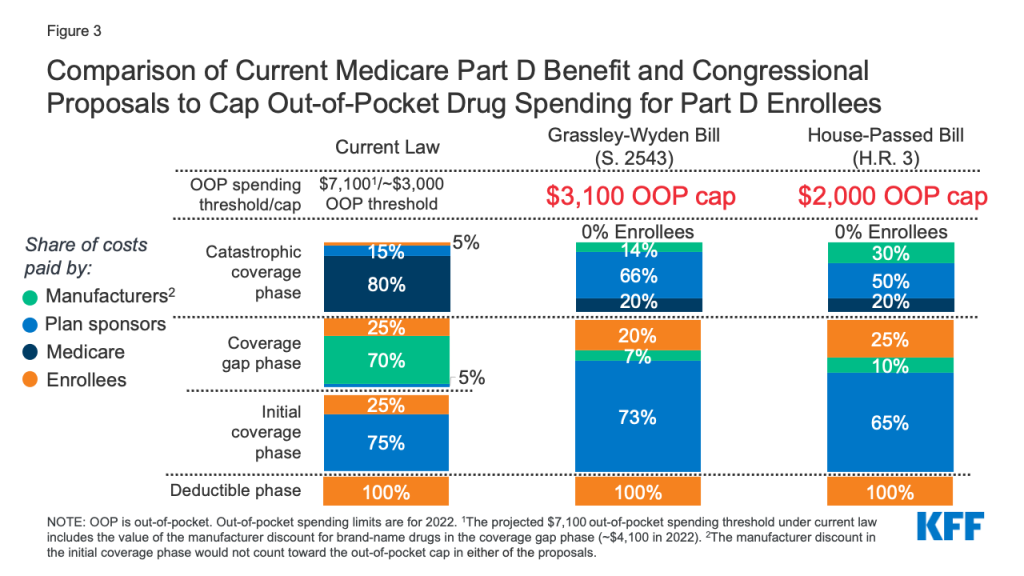

In 2020, 46.5 million of the more than 60 million people covered by Medicare are enrolled in Part D, which is a voluntary outpatient prescription drug benefit for people with Medicare, provided through private plans approved by the federal government. The Medicare Part D standard benefit includes several phases, including a deductible, an initial benefit period, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage. Under the current structure of Part D, when enrollees reach the catastrophic coverage phase, they pay 5% of their total drug costs. Some beneficiaries with low incomes and modest assets are eligible for assistance with Part D plan premiums and cost sharing through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy program, including assistance with catastrophic drug costs, but in 2020, 33.9 million Part D enrollees are not receiving this assistance.

A growing number of policymakers have expressed concern about the absence of a hard cap on out-of-pocket spending for Part D enrollees, with bipartisan support for proposals that would modify the design of the Part D benefit and establish an out-of-pocket spending limit. This proposal was included in drug price legislation that passed the House of Representatives in December 2019 (H.R. 3, Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act), legislation sponsored by Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) of the Senate Finance Committee (S. 2543, Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act of 2019), and a Trump Administration FY2020 budget proposal (Figure 3). The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has also recommended eliminating beneficiary out-of-pocket spending for high drug costs in Part D, along with changes to liability for costs above the spending limit.

Beneficiary Effects

Adding an out-of-pocket spending limit in Part D would provide substantial savings for beneficiaries who have high drug costs, and protection against exposure to high drug costs for those who may need costly medications at some point in time. Beneficiaries with out-of-pocket spending above the catastrophic threshold may be taking one high-cost specialty drug, for conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, or hepatitis C, or multiple relatively expensive drugs.

In 2017, over one million Part D enrollees had out-of-pocket spending in the catastrophic phase, with average annual out-of-pocket costs exceeding $3,200 – over six times the average for all enrollees who did not receive Part D Low-Income Subsidies that year. Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies who had high out-of-pocket drug costs in 2017 would have saved approximately $1,400 per person, on average (or $1.4 billion in the aggregate) if Part D had a hard cap on out-of-pocket spending that year, rather than requiring enrollees to pay up to 5% coinsurance in the catastrophic phase, assuming no other changes to the benefit design.

For now, there are no currently approved prescription drug treatments for COVID-19 covered under Part D. If a treatment or cure is developed, covered under Part D, and with a high price tag, a hard cap on out-of-pocket drug spending under Part D would help to address affordability concerns for beneficiaries with COVID-19 who do not receive low-income subsidies.

Budget Effects

Adding a hard cap to out-of-pocket drug spending under Part D without any other changes to the Part D benefit design would increase Medicare spending by shifting costs incurred by Medicare beneficiaries to Medicare (and by extension, taxpayers). However, the budgetary effects of adding a hard cap on out-of-pocket drug spending under Part D have not been estimated by CBO for this proposal alone. All three of the proposals mentioned above with available budget estimates – H.R.3, the Grassley/Wyden proposal, and the Trump Administration’s FY2020 budget proposal – include a hard out-of-pocket cap in addition to other changes to the Part D benefit design that would reallocate liability for catastrophic costs by reducing Medicare’s share of catastrophic costs and increasing the share paid by Part D plans and manufacturers. Therefore, the budgetary effects of these proposals are estimated together.

According to CBO, the Part D benefit redesign proposals in H.R. 3 would increase federal spending by $9.5 billion over 10 years (2020-2029); the benefit redesign proposals in the Grassley/Wyden legislation would decrease federal spending by $3.4 billion over 10 years (2021-2030); and the Administration’s redesign proposals would decrease federal spending by $1.8 billion over 10 years (2020-2029). Higher spending under H.R. 3 is likely due to a substantially lower proposed out-of-pocket cap ($2,000) compared to the Grassley/Wyden legislation ($3,100). The Administration’s proposal did not specify a dollar amount for the cap.

The total on-budget cost of these proposals is offset in part by policies that shift reinsurance costs (i.e., costs above the catastrophic threshold) from the Medicare program to Part D plan sponsors and/or drug manufacturers, which is designed to give Part D plans stronger incentives to lower costs. (For a fuller discussion of these proposals and budgetary effects, see the section “Modify the Medicare Part D Benefit Design” in A Look at Recent Proposals to Control Drug Spending by Medicare and its Beneficiaries).

Expand Eligibility for Financial Assistance with Medicare Part A and B Premiums and Cost Sharing

Under the Medicare Savings Programs, state Medicaid programs help pay for Medicare Part A and B premium and/or cost-sharing assistance for Medicare beneficiaries who have income and assets below specified levels (Tables 2 and 3). Enrollment in the Medicare Savings Programs is open to all Medicare beneficiaries, including those in traditional Medicare and in Medicare Advantage plans. Most low-income Medicare beneficiaries who qualify for Medicare premium and cost-sharing assistance also qualify for full Medicaid benefits such as long-term services and supports7 ; these beneficiaries are referred to as full-benefit dually eligible beneficiaries. (These full-benefit dually eligible beneficiaries are not the subject of the policy approaches discussed below.)

Low-income beneficiaries who receive only financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs – meaning they only qualify for payment of Medicare Part A and/or B premiums and, in some cases, Part A and Part B cost sharing but not full Medicaid benefits – are referred to as partial-benefit dually eligible beneficiaries. In 2017, there were about 3.1 partial-benefit dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries receiving financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs.8 There are three eligibility categories for this assistance, corresponding to different income and asset levels (Table 2)9 :

- Qualified Medicare Beneficiaries (QMB-only) receive assistance with their Medicare Part A and B premiums as well as deductibles and cost-sharing requirements. To qualify, beneficiaries generally must have incomes of no more than 100% FPL ($12,760/individual and $17,240/couple in 2020) and assets no higher than $7,860/individual and $11,800/couple.

- Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries (SLMB-only) receive assistance with their Medicare Part B premiums only. To qualify, beneficiaries generally must have incomes between 101% and 120% FPL ($15,312/individual and $20,688/couple in 2020) and assets no higher than $7,860/individual and $11,800/couple.

- Qualifying Individuals (QI) receive assistance with their Medicare Part B premiums only. To qualify, beneficiaries generally must have incomes between 121% and 135% FPL ($17,226/individual and $23,274/couple in 2020) and assets no higher than $7,860/individual and $11,800/couple.

The federal government sets minimum income and asset eligibility requirements for the Medicare Savings Programs, but states can choose to expand eligibility to provide premium and cost-sharing assistance to beneficiaries with higher incomes and/or assets (Table 3). There are six states, as well as the District of Columbia, that have elected to modify income eligibility criteria, either by raising the qualifying federal poverty limits or applying a more generous income disregard (Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Massachusetts, and Mississippi). Nine states and the District of Columbia have elected to eliminate the asset test (Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana, Mississippi, New York, Oregon, and Vermont), while three states have elected to have a higher asset limit (Maine, Massachusetts, and Minnesota). Those states with different eligibility requirements use state dollars to provide coverage to lower income beneficiaries who would not otherwise qualify under federal rules.

Because federal rules under the Medicare Savings Programs impose an income and asset test, not all low-income Medicare beneficiaries qualify for financial assistance with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing requirements. Some do not qualify because their income is just above the eligibility threshold, even if they have very little savings or other assets. For example, a widow living on $20,000 with just $5,000 in savings would not qualify for any assistance under these programs. Others with low incomes may not qualify if their savings exceed the maximum allowed ($7,860 for an individual in 2020).

The eligibility requirements for the Medicare Savings Programs are generally stricter than those established under the Affordable Care Act for the Medicaid expansion or Marketplace coverage. For example, under the ACA, non-elderly people who live in states that expanded Medicaid up to 138% are not subject to an asset test to determine eligibility for the Medicaid program. The ACA also provides premium tax credits and cost-sharing reduction (CSR) subsides for qualifying individuals who enroll in a health plan through the marketplace, which are not subject to an asset test. Premium tax credits are available for people with incomes up to 400% FPL, while cost-sharing subsidies are available for people with incomes up to 250% FPL.

To limit the financial burden of health care costs on low-income Medicare beneficiaries, some policymakers have proposed to modify eligibility criteria for both the Medicare Savings Programs and the Part D Low-Income Subsidy program (discussed below). Some of these changes were recently proposed by policymakers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and included in legislation that passed the House of Representatives in December 2019 (H.R. 3, Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act).

This brief explores four approaches to increase financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs:

- Provide assistance with Medicare Part A and Part B cost-sharing requirements to beneficiaries who currently qualify for Part B premium assistance (but not for assistance with deductibles or cost sharing) through the Medicare Savings Programs (e.g. SLMBs and QI enrollees with incomes up to 135% FPL).

- Expand eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs (either premium assistance only or both premium and cost-sharing assistance) to beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% FPL (up from 135% currently), keeping the current asset limits in place.

- Expand eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs (either premium assistance only or both premium and cost-sharing assistance) to beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% FPL and eliminate the current asset limits.

- Expand eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs (either premium assistance only or both premium and cost-sharing assistance) to beneficiaries with incomes up to 200% FPL and eliminate the current asset limits.

This analysis is based on national estimates and, due to a lack of state-level data, does not adjust for state-level variations in eligibility. This may affect the estimates we present here of the number of people who could benefit as well as the potential impact on Medicare and Medicaid spending. For example, we may overestimate the number of people who could benefit from eliminating the asset limits because nine states and the District of Columbia do not impose asset requirements in determining eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs. We believe our estimates serve as a reasonable approximation of the magnitude of the potential effect of these policy approaches.

Beneficiary Effects

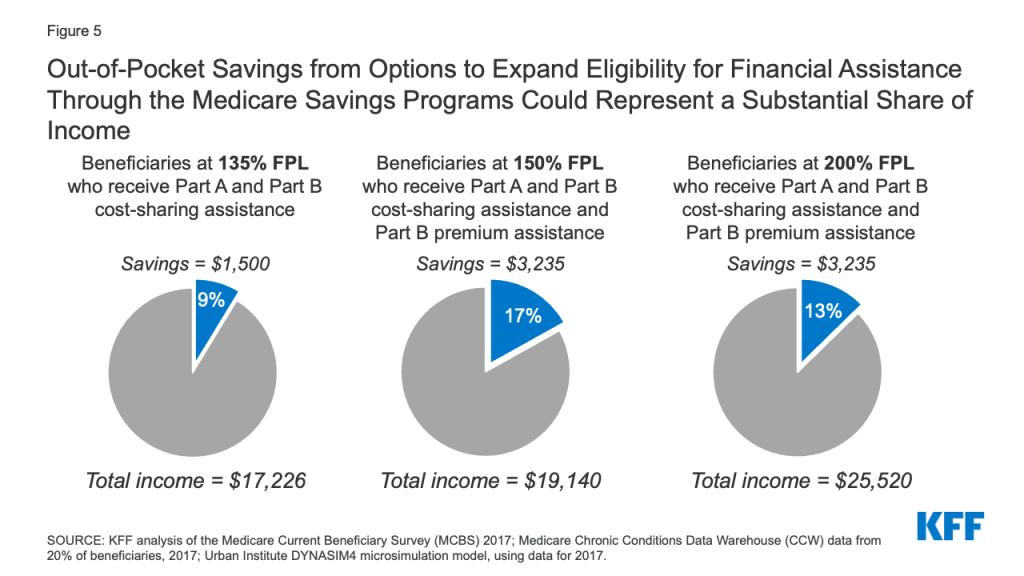

Providing assistance with Medicare cost-sharing requirements to low-income Medicare beneficiaries who are currently eligible for help with Part B premiums only (e.g. SLMBs and QI enrollees with income below 135% of poverty) would help an estimated 1.5 million beneficiaries (Figure 4). This additional financial assistance would generate average per capita out-of-pocket savings of about $1,500 per person in 2020, based on our analysis of Medicare Part A and B liability. This estimate assumes that beneficiaries do not have any other form of supplemental insurance that would cover some or all cost-sharing. In other words, a beneficiary currently eligible for Part B premium assistance only with an income approximating 135% of poverty ($17,226 in 2020), would see savings that represent 9% of annual income (more for beneficiaries with incomes below that level) (Figure 5).

Expanding eligibility for financial assistance with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing requirements to all low-income Medicare beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% of poverty (up from the current 135% FPL limit), keeping the current asset limits in place, would help an estimated 1.8 million Medicare beneficiaries. This includes 1.5 million beneficiaries currently receiving Part B premium assistance only (as noted above), plus an additional 0.3 million beneficiaries with incomes between 135% and 150% FPL. This estimate is based on the number of beneficiaries at this income level who received partial LIS benefits in 2017, and as such might overstate eligibility somewhat since LIS asset limits are higher than MSP asset limits, but it may also understate how many could potentially qualify because not everyone eligible for LIS currently participates.

Low-income Medicare beneficiaries who were not already receiving financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs could see average out-of-pocket savings of approximately $3,235 per person, including $1,735 in Part B premiums, based on the standard monthly Part B premium in 2020, and $1,500 for Part A and B cost sharing in 2020.10 For beneficiaries with incomes between $17,226 and $19,140 (135% to 150% FPL in 2020), this total savings represents between 17% and 19% of their incomes (Figure 5).

Expanding Medicare Savings Program eligibility to provide premium assistance only, or both premium and cost-sharing assistance to beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% FPL and eliminating the asset limits would help an estimated 6.7 million beneficiaries.11 This includes the 1.8 million beneficiaries who would be helped by expanding eligibility for assistance with premiums and cost sharing up to 150% FPL under current asset limits, plus 4.9 million beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% FPL with assets higher than current limits.

Among newly-eligible beneficiaries, policymakers could choose to provide different levels of assistance, such as assistance with both premiums and cost sharing to those with somewhat lower incomes and assistance with premiums only to those with somewhat higher incomes. If beneficiaries qualified for both premium and cost-sharing assistance, estimated out-of-pocket savings would be $3,235 in 2020, similar to the approach described above. If beneficiaries qualified for premium assistance, but not cost-sharing assistance (as is the case today for SLMBs and QIs), estimated out-of-pocket savings on premiums would be $1,735 in 2020.

Expanding Medicare Savings Program eligibility to provide premium assistance only, or both premium and cost-sharing assistance to individuals with incomes up to 200% FPL and eliminating the asset limits would help an estimated 12.3 million beneficiaries.12 This includes the 6.7 million individuals with incomes up to 150% FPL (as in the previous approach ) and an additional 5.6 million beneficiaries with incomes between 150% and 200% FPL. As in the previous approach, financial assistance could be provided for premiums only, or both premium and cost-sharing requirements; beneficiaries who qualify for assistance with both premiums and cost sharing could save $3,235 in 2020, while those who newly qualify for premium assistance alone could save $1,735 in 2020.

Among the beneficiaries would be helped under an approach that expanded eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs up to 200% FPL with no asset test are an estimated 3.9 million beneficiaries in communities of color (31% of the total 12.3 million beneficiaries), including 1.2 million Black beneficiaries, 1.9 million Hispanic beneficiaries, and 0.7 million beneficiaries in other racial and ethnic groups.

Another approach, which we are unable to analyze due to data limitations, would be raising, but not eliminating, the asset test – for example, raising it to $50,000, up from the highest allowable limits currently ($7,860 for individuals/$11,800 for couples). This approach would allow more beneficiaries to qualify for the Medicare Savings Programs, without providing financial assistance to the very small share of Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes but significant savings.

Budget Effects

The budgetary effects of these policy approaches have not been estimated by CBO. While H.R. 3 included a provision to expand financial assistance with Medicare Part A and Part B premiums and cost sharing to beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% FPL (keeping the current asset limits in place), CBO scored this provision together with several other Medicare low-income benefit improvements in H.R. 3, including expanding eligibility for full Part D Low-Income Subsidy benefits to individuals up to 150% FPL (up from 135% FPL), providing automatic eligibility for Medicare premium and cost-sharing subsidies to certain low-income residents of the territories, and providing automatic eligibility for Part D Low-Income Subsides to certain Medicaid beneficiaries. Taken altogether, CBO estimated that these provisions would cost an estimated $49.8 billion over 10 years (2020-2029).

The budget effects of various approaches to expand eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs would depend in part on design features. Of the approaches discussed above, the most costly of these approaches would be to expand eligibility for both Part A and Part B premium and cost-sharing assistance to beneficiaries with incomes up to 200% FPL with no asset limits. The cost could be scaled back by providing different levels of financial assistance to people at different income levels up to 200% of poverty, or by raising the income and asset test thresholds above current levels, but not to 200% of poverty and by retaining the asset test at a higher level.

These approaches would also have differential effects on federal and state budgets depending on how they were financed, and baseline eligibility criteria in each state. Because the Medicare Savings Programs are currently financed jointly by states and the federal government, any expansion in benefits or eligibility would increase costs for Medicaid if the current financing structure was used to pay for the expansion. However, if costs for Medicare premiums and cost sharing were shifted from Medicaid to Medicare, states would realize savings, shifting the impact to the Medicare program and its beneficiaries (as discussed below).

Eliminating asset tests for the Medicare Savings Program could provide some modest offsetting savings for states if they experience lower administrative expenses due to no longer having to determine beneficiaries’ assets. However, eliminating asset limits could raise the concern that some people with low incomes but significant savings would benefit from the eligibility expansion. Raising the asset limit, but not eliminating it, would maintain the need for states to determine assets, but since fewer beneficiaries would qualify for assistance than if the asset limits were eliminated, retaining the asset test would put less pressure on federal and state budgets and would address potential concerns over beneficiaries with high assets being able to qualify.

Another approach would be to have the federal government pay for the cost of the expansion, and not impose any additional costs on states, following the model of the Part D LIS program, which is fully federally financed. The cost to the federal government would reflect how many people are covered by the expansion, whether the expansion covers premiums alone or premiums and cost sharing, and whether the federal government would also assume the state share of costs for current Medicare Savings Program recipients or just the expansion groups.

If additional costs incurred by the federal government lead to an increase in Part A spending, this could put more pressure on Part A trust fund solvency, which CBO now projects will be depleted in 2024. Likewise, an increase in Medicare Part B spending would lead to higher premiums paid by beneficiaries who do not qualify for the Medicare Savings Program. On the other hand, lower-income beneficiaries who currently purchase Medigap (about 2.1 million beneficiaries) who newly qualify for financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs might choose to drop their policies, since the benefits would likely substitute for Medigap, and would therefore save the amount they would have spent on Medigap premiums ($150 per month, on average).

Expand Eligibility for Financial Assistance with Part D Plan Premiums and Cost Sharing

The Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) Program helps beneficiaries with their Part D premiums, deductibles, and cost sharing, providing varying levels of assistance to beneficiaries at different income and asset levels up to 150% FPL, which is higher than the income eligibility threshold for the Medicare Savings Program, as noted above (Table 4). In 2017, 13.7 million Medicare beneficiaries received either full or partial LIS benefits, representing 31% of all Part D enrollees that year.13

Both full-benefit and partial-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries in the Medicare Savings Programs automatically receive full LIS benefits, meaning they pay no Part D premium or deductible and only modest copayments for prescription drugs until they reach the catastrophic threshold, when they face no cost sharing. Individuals who do not automatically qualify for LIS can enroll if they meet certain income and asset requirements set by the federal government, and can receive full or partial LIS benefits depending on their income and assets. Some beneficiaries who receive partial LIS benefits pay no monthly premium while others pay a partial monthly Part D premium (with subsidies of 75%, 50%, or 25% of the monthly premium, depending on their income); all partial LIS recipients also pay an $89 annual deductible, 15% coinsurance up to the out-of-pocket threshold, and modest copayments for drugs above the catastrophic threshold.

As with the Medicare Savings Programs, the asset test for the Part D Low-Income Subsidy program disqualifies many otherwise income-eligible low-income people. Expanding financial assistance with Part D prescription drug plan premiums and cost sharing by lifting the asset test and broadening income eligibility could provide substantial savings to beneficiaries, particularly those who take high-cost drugs.

Below we discuss three policy options to make prescription drug costs more affordable for low-income people on Medicare, with the number of beneficiaries who could be helped and estimated savings under each option:

- Provide full LIS benefits for beneficiaries currently receiving only partial LIS benefits.

- Eliminate the asset limits for LIS program eligibility, keeping the current income limits.

- Expand LIS program eligibility to individuals with incomes up to 200% FPL (up from 150% FPL) and eliminate the asset limits.

Beneficiary Effects

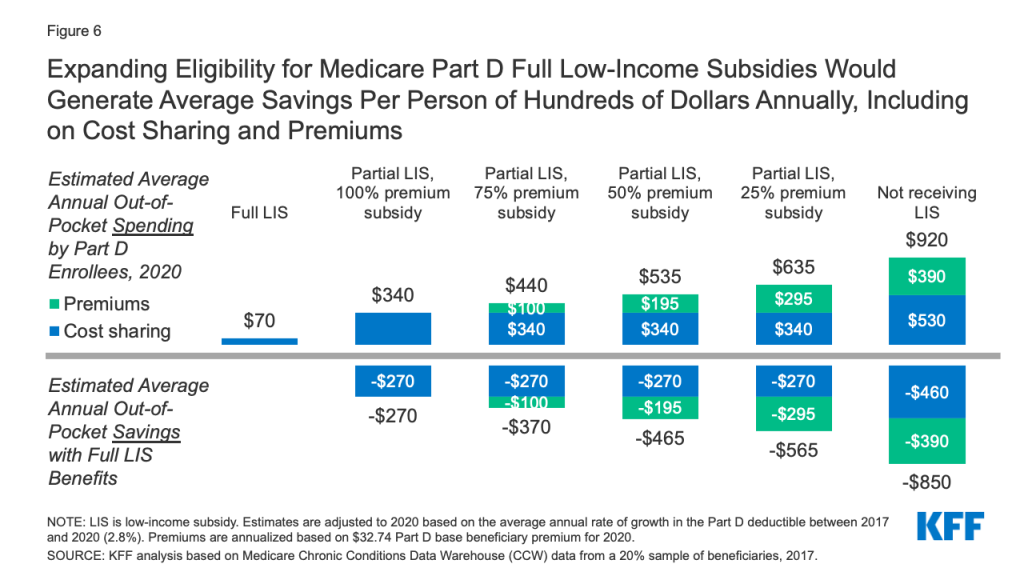

Providing full Medicare Part D LIS benefits to Part D enrollees currently receiving partial LIS benefits would help an estimated 0.4 million beneficiaries, based on 2017 enrollment. This option is similar to a provision that was included in H.R. 3. Estimated average out-of-pocket savings per partial LIS enrollee who receives full LIS benefits would range from approximately $270 to $565 in 2020, depending on the level of premium assistance partial LIS beneficiaries were receiving, as detailed below (Figure 6):

- Partial LIS enrollees who receive a 25% premium subsidy (the lowest premium subsidy level for partial LIS enrollees) would save approximately $565 on their total out-of-pocket drug costs, including approximately $270 in savings on cost sharing by moving from 15% coinsurance to modest copayments for their prescriptions and no out-of-pocket costs above the catastrophic threshold, plus $295 in annual premium savings.

- Partial LIS enrollees who receive a 75% premium subsidy would save $370 on their total out-of-pocket drug costs, including approximately $270 in savings on cost sharing plus $100 in annual premium savings.

- Partial LIS enrollees who receive a 50% premium subsidy would save approximately $465 on their total out-of-pocket drug costs, including approximately $270 in savings on cost sharing plus $195 in annual premium savings.

- Partial LIS enrollees who pay $0 premium would gain no additional premium subsidy but would save $270 on their out-of-pocket drug costs.

These averages understate the potential cost savings for the smaller share of low-income enrollees with extraordinarily high drug costs, such as partial LIS beneficiaries who take high-cost specialty drugs. This is because for high-cost drugs, with total prices in the thousands of dollars, 15% coinsurance can translate into substantial out-of-pocket costs. For example, partial LIS enrollees taking Humira or Enbrel for rheumatoid arthritis would pay around $1,700 for a year’s worth of these medications in 2020, while full LIS enrollees would pay less than $20 annually. Thus, if partial LIS enrollees received full LIS benefits, they would save just under $1,700 in 2020 on cost sharing for one of these medications alone. Annual savings would be similar for other high-cost specialty drugs, with the majority of savings occurring below the catastrophic threshold where partial LIS enrollees currently pay 15% coinsurance but full LIS enrollees pay low flat copays for brand-name drugs of either $3.90 or $8.95, depending on their income and asset levels.

Eliminating the asset limits for LIS program eligibility while keeping the current income limits would help an estimated 4.0 million low-income Medicare beneficiaries with incomes below 150% of FPL who currently do not qualify for any help under the LIS program because their assets exceed current limits.

- Estimated out-of-pocket savings per person gaining LIS coverage would be highest for beneficiaries with no LIS who qualified for full LIS. Average total out-of-pocket Part D spending is around $920 in 2020 for beneficiaries with no LIS (including premiums and cost sharing), compared to only $70 for beneficiaries with full LIS (cost sharing only). Therefore, estimated savings would be approximately $850 for these beneficiaries, including savings of $460 on cost sharing and $390 on annual Part D premiums (Figure 6).

- For beneficiaries with no LIS who qualified for partial LIS, estimated out-of-pocket savings would range from approximately $290 to $580 in 2020, depending on the level of premium assistance beneficiaries received: $290 is savings on cost sharing only for beneficiaries who go from no LIS to partial LIS, with the lowest level of premium subsidy (25%), and $580 is savings on both cost sharing and premiums for beneficiaries who go from no LIS to partial LIS, with a full premium subsidy.

Expanding LIS program eligibility to individuals with incomes up to 200% FPL and eliminating the asset limits would help an estimated 9.6 million low-income Medicare beneficiaries who would not otherwise qualify for LIS benefits. This includes 4.0 million beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% who would gain assistance if the asset limits were eliminated, and another estimated 5.6 million beneficiaries with incomes between 150% and 200% FPL. Estimated average savings for these beneficiaries would be the same as described above under the option to eliminate the asset limits for LIS program eligibility.

Budget Effects

The budgetary effects of these options have not been estimated by CBO. As mentioned in the discussion of budgetary effects under the Medicare Savings Programs, increasing financial assistance to the level of full LIS benefits for beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% FPL (up from 135% FPL) was a provision in H.R.3 and was scored with other low-income provisions in the legislation. CBO estimated that these program improvements for Medicare low-income beneficiaries would cost an estimated $49.8 billion over 10 years (2020-2029).

Unlike the Medicare Savings Programs, the LIS program is financed only by the federal government, so any expansion in benefits would be borne by the federal government, and not states. As with the Medicare Savings Programs, the budget effects of options to expand eligibility under the LIS program would depend on the design features, and could be dialed up or down. The most expensive option in terms of federal budget effects would be extending full LIS benefits to individuals with incomes up to 200% FPL without regard to assets, but the cost could be scaled back by providing different levels of financial assistance to individuals at different income thresholds.

Conclusion

In light of affordability challenges facing lower and middle-income people on Medicare, compounded by the increased financial pressure resulting from the coronavirus pandemic, many Medicare beneficiaries could realize significant savings from policy options to decrease their out-of-pocket spending on health care premiums and other medical expenses. While these potential benefit improvements and expansions of eligibility for low-income assistance would ease financial pressures among beneficiaries, these changes would increase costs for the federal government and could increase or decrease costs for states depending on how certain options were financed. At a time when both anxiety about the affordability of medical care and economic insecurity are at a high level, these policy changes could get increased attention from policymakers.

Juliette Cubanski, Meredith Freed, and Tricia Neuman are with KFF. Anthony Damico is an independent consultant.

Tables

| Table 1: Comparison of Budgetary Effects of Options to Add an Annual Out-of-Pocket Spending Limit to Medicare, Assuming Full Implementation in 2021 | |||||||

| Budget Effects (in billions) | |||||||

| Out-of-pocket spending limit | Limit applies to | Net change in Medicare liability for Part A/B services | Net change in total Medicaid liability | Net change in federal Medicaid liability | Net change in state Medicaid liability | Total Federal Budget Effects in 2021 | Total 10-Year Federal Budget Effects (2020-2029) |

| $5,000 | Beneficiary OOP | $6.0 | -$0.8 | -$0.4 | -$0.3 | $8.3 | $114.1 |

| Beneficiary OOP and Medicaid | $12.5 | -$5.9 | -$3.4 | -$2.5 | $15.0 | $205.5 | |

| All non-Medicare spending | $19.4 | -$6.0 | -$3.5 | -$2.5 | $24.6 | $332.9 | |

| $6,700 | Beneficiary OOP | $3.8 | -$0.5 | -$0.3 | -$0.2 | $5.4 | $74.1 |

| Beneficiary OOP and Medicaid | $9.2 | -$4.6 | -$2.7 | -$1.9 | $10.9 | $150.3 | |

| All non-Medicare spending | $14.7 | -$4.8 | -$2.8 | -$2.0 | $18.6 | $253.5 | |

| Income-related(% of FPL):0-150%: $3,350151-800%: $6,700801-900%: $7,500901-1,000%: $8,5001,001%+: $9,500 | Beneficiary OOP | $5.9 | -$1.0 | -$0.6 | -$0.4 | $8.2 | $118.7 |

| Beneficiary OOP and Medicaid | $13.9 | -$7.3 | -$4.2 | -$3.1 | $16.2 | $228.0 | |

| All non-Medicare spending | $20.0 | -$7.5 | -$4.3 | -$3.1 | $24.7 | $345.1 | |

| NOTE: OOP is out-of-pocket. FPL is federal poverty level.SOURCE: KFF summary of Medicare benefit modeling data from Actuarial Research Corporation. | |||||||

| Table 2: Eligibility for Medicare Savings Programs in 2020 | |||||||

Beneficiary Group | Level of Medicaid Benefits | FPL Threshold | Monthly Income Limit | Asset Limit | Benefits | ||

| Individual/ Married | Individual/ Married | Part A Premiums | Part B Premiums | Part A & B Cost sharing | |||

| Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) | |||||||

| QMB-plus | Full | ≤100% | $1,084/$1,457 | $2,000/$3,000 | √ | √ | √ |

| QMB-only | Partial | ≤100% | $1,084/$1,457 | $7,860/$11,800 | √ | √ | √ |

| Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary (SLMB) | |||||||

| SLMB-plus | Full | 101-120% | $1,296/$1,744 | $2,000/$3,000 | √ | √ | |

| SLMB-only | Partial | 101-120% | $1,296/$1,744 | $7,860/$11,800 | √ | ||

| Qualifying Individual (QI) | |||||||

| QI | Partial | 121-135% | $1,456/$1,960 | $7,860/$11,800 | √ | ||

| Qualified Disabled and Working Individuals (QDWI) | |||||||

| QDWI | Partial | ≤200% FPL* | $4,339/$5,833 | $4,000/$6,000 | √ | ||

| NOTE: FPL is federal poverty level. Alaska and Hawaii have higher income eligibility limits. Income limits include $20 monthly income disregard. Resource limits do not include $1,500 for burial expenses. *QDWI income thresholds are based on 200% of FPL and do not count half of income earned from work. Full-benefit dually eligible beneficiaries qualify for full Medicaid benefits and receive financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs. Partial-benefit dually eligible beneficiaries receive only financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs, but do not receive full Medicaid benefits.SOURCE: KFF summary of information from National Council on Aging, “Medicare Savings Programs Eligibility and Coverage Chart, 2020,” updated March 2020; Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP, Chapter 3: Improving Participation in the Medicare Savings Programs,” June 2020. | |||||||

| Table 3: Eligibility for Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs) in States with Different Income and/or Asset Limits than Federal Limits in 2020 | ||||

| State | Monthly Income Limit | Asset Limit | ||

| QMB | SLMB | QI | ||

| United States | $1,084/ $1,457 | $1,296/ $1,744 | $1,456/ $1,960 | $7,860/ $11,800 |

| Alabama | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| Arizona | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| Connecticut | $2,245 / $3,032 | $2,458 / $3,319 | $2,617 / $3,535 | No limit |

| Delaware | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| DC* | $3,190/ $4,310 | N/A* | N/A* | No limit |

| Illinois | Same as federal plus $25 disregard | Same as federal | ||

| Indiana | $1,615 / $2,175 | $1,827 / $2,463 | $1,987 / $2,678 | Same as federal |

| Louisiana | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| Maine | $1,670 / $2,255 | $1,882 / $2,543 | $2,043 / $2,758 | $58,000 / $87,000 |

| Massachusetts | $1,402 / $1,888 | $1,615 / $2,176 | $1,774 / $2,391 | $15,720 / $23,600 |

| Minnesota | Same as federal | $10,000 / $18,000 | ||

| Mississippi | Same as federal plus $50 disregard | No limit | ||

| New York | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| Oregon | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| Vermont | Same as federal | No limit | ||

| NOTE: QMB is Qualified Medicare Beneficiary. SLMB is Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary. QI is Qualifying Individual. Monthly income includes $20 monthly income disregard, except in those states that have higher income disregards or no disregard: CT includes no standard disregard; ME increased income disregard to $75 for single and $100 for couples. Maine’s asset limits apply to liquid assets only. *QMB is the sole program in DC.SOURCE: KFF summary of information from National Council on Aging, “Medicare Savings Programs Eligibility and Coverage Chart, 2020,” updated March 2020; Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP, Chapter 3: Improving Participation in the Medicare Savings Programs,” June 2020. | ||||

| Table 4: Eligibility for Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) Program in 2020 | |||||||||

| Beneficiary Group | Monthly Income Limit | Asset Limit | Premium | Cost Sharing | |||||

| Individual/ Married | Individual/ Married | Deductible | Initial Coverage | Catastrophic | |||||

| Full Low-Income Subsidy | |||||||||

| Full-benefit duals | income ≤100% FPL | State Medicaid/ MSP | State Medicaid/ MSP | $0 | $0 | $1.30 generic; $3.90 brand | $0 | ||

| income >100% FPL | State Medicaid/ MSP | State Medicaid/ MSP | $0 | $0 | $3.60 generic; $8.95 brand | $0 | |||

| Non-full-benefit duals (QMB-only, SLMB-only, QI) OR non-duals | income ≤135% FPL & lower asset levels | $1,456/ $1,960 | $7,860/ $11,800 | $0 | $0 | $3.60 generic; $8.95 brand | $0 | ||

| Partial Low-Income Subsidy | |||||||||

| Non-duals | income ≤135% FPL & higher asset levels | $1,456/ $1,960 | $7,860 to $13,110/ $11,800 to $26,160 | $0 | $89 | 15% coinsurance | $3.60 generic; $8.95 brand | ||

| income between 135%-150% FPL | $1,615/ $2,175 | $13,110/ $26,160 | Scaled | $89 | 15% coinsurance | $3.60 generic; $8.95 brand | |||

| NOTE: FPL is federal poverty level. Alaska and Hawaii have higher income eligibility limits. Income limits include $20 monthly income disregard. Resource limits do not include $1,500 for burial expenses.SOURCE: KFF summary of information from National Council on Aging; “Part D LIS/Extra Help Eligibility and Coverage Chart, 2020” updated January 2020; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Letter to All Part D Plan Sponsors: 2020 Resource and Cost-Sharing Limits for Low-income Subsidy (LIS),” November 1, 2019. | |||||||||

Methodology

Data and Methods for Adding an Out-of-Pocket Limit to Traditional Medicare

To analyze the effects of an out-of-pocket limit, KFF collaborated with Actuarial Research Corporation (ARC) to develop a model to assess the spending effects for Medicare, beneficiaries, and other payers of options to add an annual out-of-pocket limit to Medicare, assuming full implementation in 2020. The model is primarily based on individual-level data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), which are calibrated to match aggregate Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Medicare spending and enrollment estimates and projections.

We first developed a current-law baseline for 2020 by identifying Medicare reimbursements for each individual in traditional Medicare (excluding beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans), inferring the individual’s cost-sharing obligations under current law, and dividing those obligations between the individual and their supplemental insurer as appropriate. We calculated Medicare and supplemental plan premiums and added these amounts to beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs. Next, we simulated the effects of adding an out-of-pocket limit by modifying cost-sharing obligations based on various limits. We assumed that beneficiaries would use more services with an annual spending limit and that some beneficiaries would switch into or out of traditional Medicare, Medigap, or Medicare Advantage in response to this change.

Although MCBS includes Medicare beneficiaries who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage, we excluded this group when evaluating the individual-level spending effects of adding an out-of-pocket limit because the option modifies traditional Medicare. The model does incorporate indirect effects on aggregate Medicare Advantage spending and enrollment, based on the assumptions that changes in traditional Medicare reimbursement would be reflected in Medicare Advantage payments, and that aggregate Medicare Advantage payments will change to the extent that some beneficiaries switch between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage.

Data and Methods for Options to Improve Financial Protections for Low-Income Beneficiaries

For these options, our analysis uses data from the following sources: the CMS Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2017 Survey file; a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries from the CMS Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW), 2017; and the Urban Institute’s DYNASIM4 microsimulation model, using data for 2017.

Some people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid have incomes and/or assets higher than the MSP and LIS eligibility limits because some states do not have asset tests and/or have higher income limits for their Medicare Savings Programs. States may also allow people with higher incomes and/or assets to qualify for Medicaid through specific pathways, such as the nursing home or medically needy pathways. All Medicare beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicaid automatically qualify for Part D LIS benefits, irrespective of their incomes and assets. The total number of people receiving MSP and Part D LIS benefits in 2017 came from the CCW.

We estimated the number of additional people who could be eligible for Medicare Savings Program benefits and Part D LIS benefits if eligibility criteria were changed to allow all people with incomes below 150% of the poverty level (FPL) to be eligible, with no limits on assets. The MCBS provided information about the distribution of income among people receiving Medicare Savings Program and Part D LIS benefits. The data from the DYNASIM model was used to estimate the total number of people with incomes below 150% of the FPL. The estimated number of MSP beneficiaries with incomes below 150% of the FPL was subtracted from the estimated total number of people with incomes below 150% of the FPL to estimate the number of additional people who would be eligible for the MSPs if the income threshold was 150% of the FPL and no asset test was imposed. The same process was used to estimate the number of Part D LIS beneficiaries who would be eligible if the income threshold was 150% of the FPL and no asset test was imposed.

We then estimated the number of additional people who would be eligible for MSPs and LIS if the income threshold was raised from 150% to 200% of the FPL, with no restrictions on assets. The MCBS was used to estimate the number of MSP beneficiaries who have incomes between 150% and 200% of the FPL. That estimate was then subtracted from the total number of people with incomes between 150% and 200% of the FPL, with the latter estimate coming from the DYNASIM model, to produce an estimate of the number of additional people who would be eligible for MSP and LIS if the income threshold was raised from 150% to 200% of the FPL, with no asset test.

The resulting estimates overstate the number of people who would be newly eligible for the MSPs and LIS under the expanded eligibility criteria because the estimates do not account for the Medicare beneficiaries who are eligible for these programs under existing income and asset limits but are not enrolled.

To estimate average savings that beneficiaries might achieve through expansions in eligibility for the Medicare Savings Programs, we estimated average annual Medicare Part A and B liability for individuals not receiving cost-sharing assistance through the MSPs using the 2017 CCW. Liability was based on beneficiaries in traditional fee-for-service who do not have Medicaid and represents the amount of cost sharing that beneficiaries would incur if they do not have any form of supplemental coverage. We inflated the 2017 average amount to a 2020 value using the average of the values for the average annual rate of growth in the Part A deductible between 2017 and 2020 (2.3%) and the average annual rate of growth in the Part B premium between 2017 to 2020 (2.6%); averaging these two values gave us a growth rate of 2.4%. This method assumes no change in utilization between 2017 and 2020. Savings on Part B premium is calculated based on the 12 months of the standard Part B premium for 2020.

A similar process was used to calculate how much individuals would save if they received cost-sharing assistance through the LIS program. We calculated average annual cost sharing on prescription drugs for non-LIS, partial LIS, and full LIS enrollees using Part D prescription drug event claims from the 2017 CCW. We inflated average spending on prescription drug cost sharing for these three groups of enrollees using the average annual growth rate in the Part D deductible from 2017 to 2020 (2.8%). We calculated average savings on cost sharing by taking the difference in average spending between various groups (such as the difference between average spending by full LIS enrollees and partial LIS). The calculation of premium savings is based on the Part D base beneficiary premium for 2020 ($32.74 per month); premium savings range depending on the level of premium subsidy received (full LIS enrollees receive a full premium subsidy; partial LIS enrollees receive premiums subsidies ranging from 100% to 25% of the monthly premium; non-LIS enrollees receive no premium subsidy). Estimated out-of-pocket savings for specific drugs is based on 2020 data from the Medicare Plan Finder. Using the plan finder for zip code 20902 in Maryland, we entered specific drugs and retrieved annual cost-sharing information for non-LIS, partial LIS, and full LIS enrollees, using amounts for the lowest-cost plan in the zip code based on prices at Costco, CVS, and Giant pharmacies located within this zip code. As with the overall average cost sharing savings calculation, we calculated savings on cost sharing for specialty drugs by taking the difference in spending on specific drugs across the three enrollee groups (non-LIS, partial LIS, and full LIS enrollees).

Endnotes

- The lower bound estimate in both ranges is based on the number of beneficiaries with income below 150% FPL based on KFF analysis of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 2017; the upper bound estimate is based on the number of beneficiaries with income below 150% FPL based on KFF analysis of Urban Institute DYNASIM4 microsimulation model, 2017. ↩︎

- Unpublished estimates of KFF analysis of Urban Institute DYNASIM4 microsimulation model, 2017. Asset data in the DYNASIM4 model corresponded to $12,140 for individuals and $24,250 for couples in 2017, so these estimates slightly overstate the number of people with assets above the allowable limit in 2017 ($12,320 for individuals, $24,600 for couples). ↩︎

- KFF analysis of the CMS Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 2017; differences are statistically significant. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of the CMS Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 2017; differences are statistically significant. ↩︎

- The savings estimates for the $5,000 and $6,700 limits are similar because of the shape of the out of pocket and Medicaid spend distributions, particularly the portion between the two limits of $5,000 and $6,700. While individuals with eligible spending above $6,700 would have their spending reduced by an additional $1,700 under the lower limit, this additional reduction is roughly offset by individuals with spending between the two limits, who have modest reductions in spending under the lower threshold but are not affected at all by the policy at the higher limit. ↩︎

- Medigap policies vary widely, both across policy types and across insurers. Estimates vary, but the average monthly premium was about $150 in 2019. See https://www.ehealthinsurance.com/medicare/supplement-all/how-much-medicare-supplement-plans-cost, https://www.markfarrah.com/mfa-briefs/continued-year-over-year-growth-for-medicare-supplement-plans/ ↩︎

- Full Medicaid benefits generally include services not covered by Medicare, such as inpatient hospital and nursing facility services when Medicare limits on covered days are reached. States may also choose to cover additional benefits, including durable medical equipment, personal care and other home- and community-based services (HCBS), dental care, vision, and hearing services. ↩︎

- Another 8.9 million received full Medicaid benefits in addition to financial assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs. KFF analysis of the CMS Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse Medicare data from a 20% sample of beneficiaries, 2017. ↩︎

- There is one other category of Medicare Savings Programs: Qualified Disabled and Working Individuals (QDWI); these are individuals who have lost free Medicare Part A benefits because of their return to work but are eligible to purchase Medicare Part A. Through the Medicare Savings Programs, QDWIs receive assistance with their Medicare Part A premiums only. Enrollment in QDWI represents about 325 individuals. ↩︎

- We do not include estimates for savings on Part A premiums because about 99% of beneficiaries do not have to pay a Part A premium. ↩︎

- This estimate may overstate the number of beneficiaries who could be helped by this expansion since some beneficiaries live in states that have higher income and/or asset limits and are currently eligible but not enrolled in the program. KFF analysis of Urban Institute DYNASIM4 microsimulation model and 2017 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of the CMS Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse Medicare data from a 20% sample of beneficiaries, 2017. ↩︎