Money Follows the Person: A 2015 State Survey of Transitions, Services, and Costs

Key Findings

Transitions

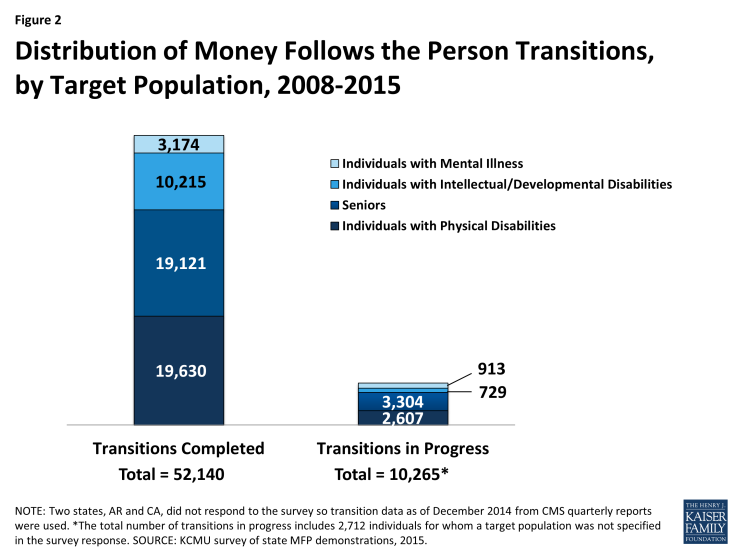

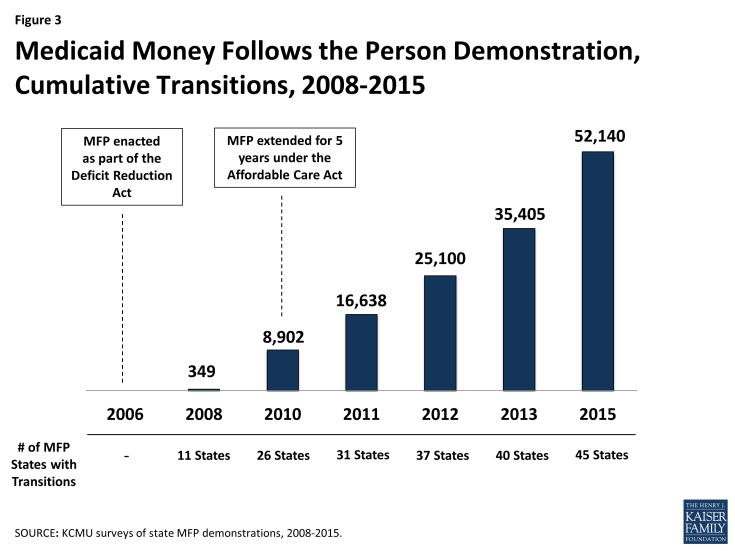

Total cumulative transitions surpassed 52,000 individuals by early 2015, as MFP states continue to increase the number of transitions each year and expand LTSS options in favor of HCBS. As of mid-2015, 52,140 Medicaid beneficiaries had enrolled in MFP and another 10,265 transitions were in progress (Figure 2). This represents an increase in cumulative enrollment of 16,740 individuals since 2013, up from 35,400 in 2013 and nearly 17,000 in 2011 (Figure 3). Most transitions (38%) occurred in three states (TX, OH and WA). These three states have consistently been the leading states in cumulative transitions since the demonstration began. MFP participant numbers vary widely across states, depending on factors such as length of program operation, size of eligible population, and state capacity and experience in operating transition programs. States with newer demonstrations, such as South Dakota and Montana, had the fewest number of cumulative transitions in 2015.

The majority of states (30 of 43) reported being on pace with annual transition targets. Thirteen states reported that they were not on pace to meet their annual projections. Reasons for this included lack of safe, affordable, accessible housing, higher acuity of nursing facility residents, provider capacity issues, and successful diversion efforts. Newer grantee states, those implementing after 2013, were more likely to report coming up short with annual transition projections compared to more established MFP states. These states may have faced initial transition hurdles in the early phase of the demonstration when MFP programs were not yet fully staffed and provider capacity and other community resources were first being tested.

Twenty-one states expect the rate of enrollment growth to increase over the next year, down from 34 states in 2013. Thirteen states anticipated no change in annual enrollment, and eight states did not know. No state anticipated a decrease in enrollment. Among the top 10 states in cumulative MFP enrollment that responded to the survey (including TX, OH, WA, CT, MI, MD, PA, IL, GA, and NY), Illinois experienced the largest change in cumulative enrollment since 2013 (97%) while Georgia experienced the smallest enrollment growth (6%) since 2013. Illinois credited its transition increase to the use of a cloud-based care management system that allowed for improved interagency communication, more efficient follow-up with referrals, and expanded access to case-specific information. Georgia attributed its slowed progress to a moratorium on transitions during 2014 that delayed the transition of individuals with behavioral health needs and developmental disabilities living in state institutions. Nine of these ten states experienced enrollment growth greater than 25 percent between 2013 and April 2015.

“The benchmark for this year has increased, as it will for next year, but attainment of even higher MFP transition rates is becoming less assured.” – MFP Project Director

In 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) awarded additional funding to five states (MN, ND, OK, WA, and WI) for the MFP Tribal Initiative to help tribal groups in their states establish transition programs for their communities. The MFP Tribal Initiative offers existing MFP states and tribal partners the resources to build sustainable community-based LTSS specifically for Indian country. Most states were still in the planning phases of the Tribal Initiative at the time of this survey. Minnesota was the only state to report transitioning a participant through a Tribal Initiative.

Participant Characteristics

In 2015, MFP Project Directors reported the following characteristics of MFP participants:

- The majority of MFP participants are individuals with physical disabilities (38%) and seniors (37%), while one in five MFP participants is an individual with an intellectual/developmental disability (I/DD). Seniors and people with physical disabilities also lead the number of transitions in progress.

- The average age of MFP participants was 57 years old. The average age of senior MFP participants was 75. MFP participants with I/DD were younger (on average 42 years old) than individuals with a mental illness or a physical disability, who averaged 44 and 51 years old, respectively.

- MFP participants averaged four months to transition back to the community, up from 3.5 months reported in 2013 and 2012. Individuals with I/DD, mental illness and people with physical disabilities took longer to transition home compared to seniors.

- MFP participants most often transitioned to an apartment. Seniors were more likely to transition to a house (their own or a family member’s) or an apartment, whereas individuals with I/DD more often transitioned to a small group home with four or fewer residents.

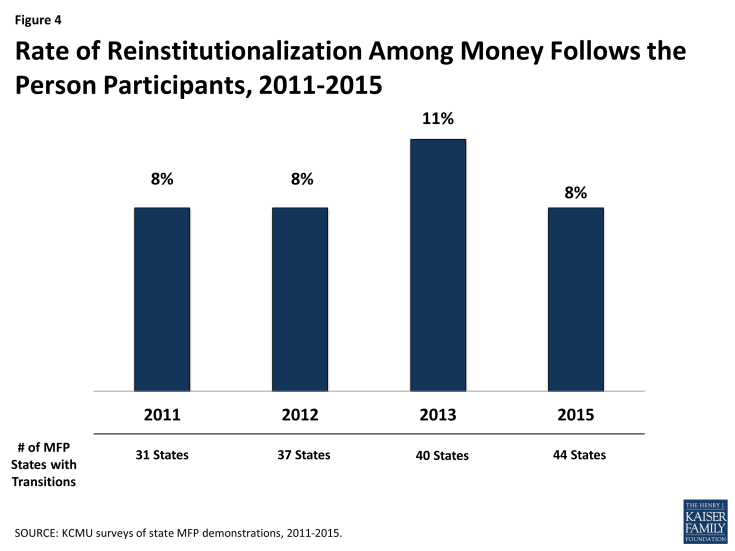

The average reinstitutionalization rate was eight percent, down from 11 percent reported in 2013 and on par with what states reported in 2011 and 2012 (Figure 4). Reinstitutionalization is defined as returning to a nursing facility, hospital, or ICF/DD, regardless of length of stay, during the beneficiary’s MFP participation year. Across all target populations, seniors were most likely to be reinstitutionalized, and individuals with I/DD were the least likely to return to an institutional setting.

Transitions for Beneficiaries with Mental Illness

States are steadily increasing transitions among individuals with mental illness, realizing a 77 percent increase in cumulative transitions for this population in less than two years. While individuals with mental illness (along with those with I/DD) represent a smaller percentage of MFP participants due to their typically more extensive medical and LTSS needs, as of mid-2015, the overall number of transitions climbed to 3,174 for individuals with mental illness (up from 1,790 in 2013). Over time, the percentage of MFP participants with mental illness has risen from just 1.4 percent in 2010 to 6 percent of total MFP transitions in 2015.

Just under half (19) of MFP states reported trying to increase the number of transitions for people with mental illness, relying on a number of strategies to do so. States cited increased outreach and education to nursing facilities as a way to generate MFP transitions for this population. Maryland hired a behavioral health specialist who is responsible for building relationships with behavioral health providers, advocates, and consumers; training providers on coordinating behavioral health services; and providing direct support to beneficiaries during the transition process. Other state efforts to target people with mental illness include adding new demonstration services such as substance abuse, peer support services, and enhanced adult foster care services (such as overnight care and medication support). Ohio is a leading state in transitioning individuals with mental illness, helping over 1,900 individuals return to community living under MFP. Ohio’s MFP program works closely with the Ohio Department of Mental Health & Addiction Services through the “Recovery Requires a Community” program that provides additional non-Medicaid services such as debt elimination to MFP participants who have mental health or substance abuse issues. Due to demand and population size, Ohio expects transitions for those with mental illness to continue to increase.

States with managed LTSS (MLTSS) programs reported working with managed care organizations (MCOs) to help coordinate service provision and to prioritize transitions for this population. For example, in Texas, MCOs are now responsible for providing mental health rehabilitative services, mental health targeted case management, and nursing facility services, in addition to being responsible for transitions. By carving-in these benefits, MCOs have the opportunity to serve beneficiaries with behavioral health needs across a range of settings. Additionally, the state has conducted trainings with MCOs to incorporate best practices learned from its MFP behavioral health pilot – a program that integrates mental health and substance abuse services with HCBS. Other states reported expanding Medicaid provider networks (in both fee-for-service and managed care environments) so that individuals with mental illness have more choices in behavioral health providers.

States also reported leveraging financial incentives to help foster transitions for people with mental illness. Washington has had “some success” in helping move children and young adults out of state hospital settings by providing financial incentives through a combination of MFP enhanced match and MFP rebalancing funds. Illinois used funding from the Balancing Incentive Program (BIP) to expand mental health services to MFP participants in under-served communities. Assertive Community Treatment and Community Support Team services are available to some participants in Illinois; these include counseling services with an emphasis on community living skills, assistance with medication management, identification of risks, and connection to resources. These services may include visits from mental health agency staff, sometimes daily in the initial weeks after transition.

Outreach, Referrals, and Transition Support

By 2015, most MFP states had several years of experience transitioning participants back to the community and have learned which outreach and enrollment strategies are most successful in identifying potential MFP participants. These initiatives are paving the way for more individuals to live in their choice of setting. We asked states to describe these strategies and the most frequent responses included:

“The most successful outreach is based on partnerships and a promotion of a philosophical framework which supports the person in choosing where they receive their LTSS, rather than the system deciding for them.” – MFP Project Director

- Statewide communication and outreach to nursing facilities, institutions for mental diseases, and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disability (ICF/DDs) (14 states);

- Presence of transition teams in nursing facilities to help with outreach and education to potential participants and their families (including peer outreach and options counseling) (12 states);

- Partnerships with local Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs), Centers for Independent Living (CILs), and long-term care (LTC) ombudsman programs (11 states);

- Including MFP with Minimum Data Set Section Q requirements (regarding residents’ interest in learning more about a return to community living) (10 states);

- Advertising and recruitment materials, including brochures, websites, and television ads that promote the demonstration (9 states); and

- Working with MCOs to prioritize transitions (5 states).

Nevada’s most successful outreach strategy is the use of a weekly level of care report. This report provides state staff with information about the most recent Medicaid beneficiaries who have been screened for nursing facility placement.

Tennessee requires staff responsible for coordinating care in its MLTSS program to assess individuals for their desire and ability to transition at least annually. In addition, to further incentivize MCOs, contracts with the state offer incentive payments upon (1) successful transition of each demonstration participant, and (2) community living for the entire 365-day demonstration period, without re-admission to a nursing facility.

Benefits

Using MFP enhanced funds, all MFP states (43 reporting) offer HCBS waiver services to MFP participants, and 36 states offer HCBS to MFP participants under their state plan benefit package to successfully transition individuals home and keep them living in the community. Services that qualify for the MFP enhanced federal matching rate during a beneficiary’s MFP participation year are those waiver and state plan services that will continue once the individual’s MFP transition period has ended. Common Medicaid HCBS are personal care, adult day health care, case management, homemaker services, home health aide services, habilitation, and respite.

Thirty-nine states offered MFP demonstration services in 2015, which are additional Medicaid HCBS reimbursed at the enhanced MFP federal matching rate during a beneficiary’s 12-month MFP participation period. MFP demonstration services are provided in a manner or amount beyond what a typical Medicaid HCBS beneficiary receives and are not otherwise available to a Medicaid beneficiary. For example, transition coordination services help MFP participants secure housing, pay for moving expenses, and secure assistive technology. After the beneficiary’s transition year ends, states are not obligated to continue MFP demonstration services but may choose to fund them through Medicaid at the state’s regular federal matching rate.

Nineteen states offered MFP supplemental services or services which are not necessarily long-term care in nature. MFP supplemental services are only offered during the beneficiary’s demonstration transition year and are reimbursed at the state’s regular federal matching rate. Eighteen states reported offering both demonstration and supplemental services. These services include benefits such as coverage of one-time housing expenses (such as security deposits, utility deposits, and furniture and household set up costs), assistive technology, employment skills training, 24-hour back-up nursing, home-delivered meals, peer-to-peer community support, and LTC ombudsman services.

Just over half (23 of 43) of the states reported making changes to MFP benefits over the past year, up from 14 states making benefit changes in 2013. Of the states making benefit alterations, 16 states reported expanding services and seven states reported eliminating services or a neutral change. Examples of restructuring of services included adding first month’s rent to transition assistance, informal caregiver’s support, peer support, and adaptive technology as demonstration services and increasing pre- and post-transition funding for environmental accessibility adaptions, pre-transition staff training, and supports coordination fees. One state reduced some of the services funded through MFP, such as physician consultation, healthcare communication, and legal consultation, due to their non-usage. The state attributed the non-usage to decreased need as a result of transition coordinators’ growing knowledge of community-based resources and relationship building with service providers over the course of the demonstration.

“Staff retention of the transition coordinators has proven invaluable to community networking and referral/resources building which has lessened the need for MFP to pay for some of the categories that were originally funded.”

– MFP Project Director

States identified service coordination/case management as the most critical service for MFP beneficiaries both pre- and post-transition. The 2015 survey asked states to describe the most critical strategies or innovative services that help MFP beneficiaries successfully transition to the community. Services were grouped into pre-transition services and post-transition services. Pre-transition services are offered to MFP participants to help position them for the greatest opportunity for success. Post-transition services include all Medicaid HCBS waiver services as well as MFP demonstration and supplemental services that support individuals living in the community.

The most frequently cited essential pre-transition services were support from transition specialists (also known as transition coordinators or navigators); transition coordination services that may include a transition budget for household items, set-up fees, or deposits for utility access; and housing assistance. Access to a transition coordinator before discharge is critical so that MFP participants can have paid and non-paid supports set up in the community before they are discharged home. Other critical pre-transition supports identified by states include: options counseling (provided by locals Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) and CILs), intensive case management (that may include a readiness assessment to develop a plan for successful transition), peer mentorship, independent living skills training, assistive technology, and access to non-medical transportation to obtain documentation for housing and/or locate housing.

“Extensive needs assessments while in the facility help to develop a plan for successful transition.” – MFP Project Director

- Colorado uses multi-disciplinary transition teams made up of the beneficiary, providers, family, friends, or anyone else the beneficiary would like to have on their team. The team provides support to the MFP participant, addresses questions/concerns, and helps identify risks/mitigation plans to ensure a successful transition and high quality of life upon transition.

- In Illinois, transition engagement specialists provide outreach and education about MFP to work with nursing facility residents. In completing their assessments, the specialists “improve the quality of the referrals received,” while also promoting collaboration across state programs in order to address the complex health conditions and physical limitations of the MFP participants.

“Early in the demonstration it became clear that for many participants, this on-going intensive case management, including 24/7 care coordination, would be instrumental to the success of participants in the community.” – MFP Project Director

The most commonly reported strategy, with regard to post-transition services, was the use of “more intensive” transition coordination/case management services. The role of the transition coordinators post-transition is to monitor the MFP participant with follow-up visits and ensure services are received in a timely manner, as scheduled, and with trained caregivers. A more intensive follow along is designed to ensure that the MFP participant has the appropriate level of monitoring and that changes to their service and risk mitigation plans can be made as needed. Several states extend transition coordination for the full 365 days after transition. In New York, transition coordinators communicate with MFP participants for a two-year period post-transition. Other notable post-transition strategies/supports include access to crisis response services (including a 24-hour back-up system to provide support and assistance for services that were not delivered), the provision of basic furnishings, groceries, and housewares to the new home, increased capacity or “slots” for HCBS waiver programs, and a focus on community engagement through social and vocational opportunities. Twenty-six states offer employment supports and services to MFP participants who are interested in returning to work or who want to pursue volunteer opportunities, although a 2012 study found a small share of MFP participants ever accessed employment services.1

In Missouri, all information about MFP participants from the initial referral, options counseling, all the way through the transition, and post-transition is entered into a web-based system. MFP staff, regional staff, and transition coordinators all have access to the system. This system allows the state to see why individuals who are interested in returning to the community cannot, and, the underlying reason if a transition was not successful. The system also captures such things as, what type of housing the participant is using, if they are living alone, if they are self-directing their HCBS, any hospitalizations, date and cause of death, age, etc. There are also note areas for transition coordinators to leave anything that might have an important bearing on the case.

Forty states are offering self-directed services, but only an estimated 16 percent of MFP participants chose this option in 2015, down from an estimated 19 percent in 2013 and 22 percent in 2012. Only three states responded that self-direction was not an option in their MFP demonstration. Self-direction is an alternative to the provider management service delivery model which offers Medicaid beneficiaries the authority to make decisions about some or all of their services, including who provides services and how they are delivered. For example, an MFP participant may be given the opportunity to recruit, select, and supervise direct service workers. Participants may also have decision-making authority over how the Medicaid funds in a budget are spent.

Self-direction participation rates varied widely across the states. Three states (DE, MA, and OH) reported 100 percent participation in self-direction due to the fact that one-time home set-up funding was categorized as a self-directed service. Seventeen states reported the percentage of MFP participants who self-direct services to be 5 percent or less. Thirteen states reported an increase in the percentage of participants who utilized self-directed options over the past year, up from nine states in 2013 and eight states in 2012. Twenty-two states reported no change in the percentage of MFP participants who self-direct and four states reported a decrease.

Financing

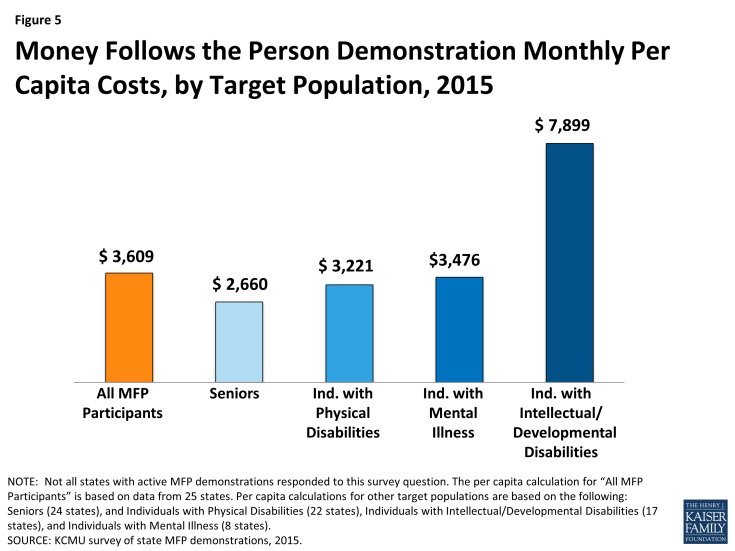

The average monthly per capita cost of serving an MFP participant in the community was $3,609 in 2015 (Figure 5), down from an average of $3,934 in 2013 and $4,432 in 2012. Average monthly per capita costs varied across states from a low of $1,260 to a high of $8,737 per person per month, based on responses from 25 states. Differences in per capita costs may be attributable to differences in covered services and/or a reflection of the diverse needs of the target populations. In comparison, the national average per user spending on Medicaid HCBS only, including Section 1915(c) waivers and the home health and the personal care services state plan benefits and excluding other Medicaid-covered services, was $17,174 in 2011.2 Average MFP monthly costs were highest for people with I/DD ($7,899) followed by individuals with mental illness ($3,476), individuals with physical disabilities ($3,221), and seniors ($2,660).

Figure 5: Money Follows the Person Demonstration Monthly Per Capita Costs, by Target Population, 2015

When asked to compare per capita costs for MFP participants with per capita costs for other Medicaid beneficiaries receiving HCBS, 18 states said costs were comparable, eight states reported that per capita costs were higher for MFP participants, and six states reported per capita costs were lower for MFP participants. The remaining states did not answer the survey question. When asked to compare the per capita costs for Medicaid beneficiaries who reside in institutions to per capita costs for MFP participants, thirty states reported that per capita costs were lower for MFP participants. Two states reported that the two costs were comparable (due to equal capitation rates for beneficiaries enrolled in managed care living in the community or in an institution), and no state reported that institutional care was lower. Responses to this survey question have remained consistent over time, with the majority of MFP states reporting MFP per capita costs for beneficiaries receiving HCBS to be lower than those residing in institutions.

MFP Staffing and Key Partnerships

“The expertise of the contracted staff and their knowledge of community resources is key to making the transition a success.” – MFP Project Director

MFP has enabled states to add program staff to help grow their transition programs and more effectively respond to transition challenges. States rely on numerous MFP staff and key partnerships to conduct outreach, coordinate efforts across state agencies, monitor quality, and assist in LTSS rebalancing efforts. Each state tailors their MFP program to meet specific needs, however, all MFP states employ a project director, and sometimes an associate/assistant project director, with MFP administrative funds. The Project Director’s role is to oversee all aspects of the demonstration including financial management, outreach/training, staffing, evaluation, project planning, and submission of required federal reporting. Other frequently reported MFP staff positions hired with 100 percent administrative funds included transition coordinators, outreach and education coordinators, housing specialists, data/fiscal analysts, quality specialists, and administrative support staff. Eight states employ an MFP quality assurance specialist. Maryland hired two quality and compliance specialists whose duties are to ensure new applicants are moving through the eligibility process in a timely manner, which includes monitoring time frames for medical assessments by the local health departments, plan of service review, provider and participant enrollment, and the eligibility determination process.

“Including a housing coordinator as part of the transition team has been found to be a critical strategy in successfully transitioning individuals to the community.” – MFP Project Director

Thirty-one states employ a housing coordinator to help with transitions, and some states employ multiple housing coordinators. These individuals function as a critical link between MFP participants and local housing resources. They can help individuals locate housing in preferred areas, negotiate lease terms with landlords, and assist with completing and acquiring needed documents for housing applications. Hawaii’s MFP housing coordinator developed a “housing stabilization tool” to assure quality transition planning and follow-up stabilization progress in the community by assessing issues such as finances (bills and rent paid on time) and safety (keeps house clean, knows how to use equipment). MFP staff are beginning to train health plan service coordinators and community case managers to use this tool.

Aside from MFP-funded positions, states rely on a number of partnerships to further their efforts to transitions individuals out of institutions and back to the community. These partnerships include working closely with local AAAs, CILs, other state agencies (such as public housing and behavioral health), LTC ombudsman programs, community stakeholders/advocacy groups, and family members.

Quality

States identified the CMS Quality of Life (QoL) survey as their main tool to measure quality and satisfaction among MFP participants, although only a handful of states (8) reported using the results from the QoL survey to make changes to their MFP demonstrations. This survey is administered within 30 days of transition and at 11 and 24 months post-discharge. The data from the QoL survey informs states about MFP participants’ health challenges, satisfaction with certain aspects of their lives in the community, their extent of independence and control over their circumstances, and the service and support gaps that result in their needs and wants not being met. Examples of changes that states made based on QoL survey findings include adding new demonstration services such as peer supports services to help with community integration and informal caregiver supports and training to address the needs of family and friends providing services. Hawaii added supportive employment services, based on the QoL question concerning the desire to work or volunteer. In doing so, the state has “developed a better relationship” with the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation and the state First-to-Work Program that provides employment preparation and support services to TANF households. New Jersey developed a Risk Review Form, based upon the responses received from the MFP QoL surveys, that was designed to indicate if an individual’s health and safety might be in jeopardy. The Risk Review Form is given to the MFP quality assurance specialist who is responsible for the follow-up with the appropriate staff and for documenting all responses and resolutions. In addition, if a Risk Review Form is generated from a first or second year follow up QoL survey administered to an individual who has been re-institutionalized, then the MFP quality assurance specialist arranges a face-to-face visit with the individual to further assess their quality of life in the institution and ascertain if the individual has any interest in returning to the community.

States also reported embedding MFP participants into the traditional quality standards – Medicaid quality improvement and quality assurance processes – that are in place through Section 1915(c) waivers and state plan assurances. Other examples of quality activities include monitoring the rate of reinstitutionalizations and the use of intensive case management for each participant during the demonstration year to monitor the delivery and quality of services. Additionally, some states conduct their own evaluations separate from CMS requirements. For example, Missouri gathers information on MFP participants that leave the program to gain insight into the reasons for their leaving. This information is used to identify trends and aids in the development of supports and services to help maintain support for individuals living in community settings. The state also noted that this insight will be important as individuals with more complicated needs return to the community. In New Jersey, MFP participants with intellectual disabilities transitioning from a Developmental Center to a community setting have the added benefit of an enhanced monitoring process – the Olmstead Review Process – that follows an individual’s transition to the community with a face-to-face follow-up review after 30, 60, and 90 days. Data collected at each review helps guide decisions about needed modifications to plans of service to mitigate issues, and to inform infrastructure decisions.

Issues Facing MFP in 2015 and Beyond: Housing, HCBS Providers, and Managed LTSS

Twenty-five states reported finding affordable, accessible housing to be the number one barrier to transitions. Housing has remained a consistent challenge since the inception of MFP. This is because MFP participants often have ongoing and persistent cognitive and physical impairments and chronic conditions that result in the need for assistance with activities of daily living and also lack adequate income and resources to afford fair market rent on their own (since Medicaid does not pay for housing in the community). Each year more MFP states have hired housing coordinators (or housing specialists) to assist individuals interested in transitioning with locating and securing housing. Other strategies to address housing shortages include partnering with state housing authorities and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to help secure Housing Choice vouchers for MFP participants, provide training on housing issues, assistance in finding housing, and assistance with the development of new housing resources. States reported securing HUD Section 811 grant funding to provide interest-free capital advance and operating subsidies to nonprofit developers of affordable housing for people with disabilities and project-based rental assistance.

- Illinois has been awarded Section 811 Project-Based Rental Assistance Demonstration funding and is in the process now of awarding Section 811 rental assistance contracts in areas needed and preferred by the participants. In addition, the state is collaborating with several local Public Housing Authorities to implement projects combining project-based and tenant-based vouchers dedicated to MFP participants. A web-based housing search system exists, and a new wait list system to prioritize and filter participants for matches with available Section 811 units came online June 1, 2015.

- Maryland is working to implement the MFP Bridge Subsidy Program that will provide a total of $2 million in rental subsidies for MFP-eligible individuals transitioning from nursing facilities and state residential centers back to the community through the use of HCBS waivers. The MFP Bridge Subsidy will offer rental subsidy for three years. After the three years, the Public Housing Authority will offer the individual a Housing Choice Voucher. Maryland also developed the Partnership for Affordable Housing to coordinate efforts for the MFP population and engage in training and outreach at the case manager level as well as systems level advocacy with developers, public housing authorities, and other housing financers.

Other housing supports include access to rental assistance programs, security deposit guarantee programs, housing counseling services, accessibility modifications, and assistive technology. A number of states also reported using MFP funds to enhance housing resource websites.

- Ohio’s Temporary Ramp Project provides modular aluminum ramps for MFP participants with an immediate need for this assistance. Depending on the participant’s specific situation, different types of vouchers, short-term rental subsidies, monetary support, and Emergency Rental/Utility Assistance are available. Also, Ohio was recently awarded HUD Section 811 funding and will be partnering with the Ohio Housing Finance Agency to develop over 500 units targeting individuals with low incomes who are transitioning through MFP.

About half (22) of MFP states reported an adequate supply of direct care workers in the community in 2015, down from tw0-thirds of states in 2013. States recognize that workforce initiatives are a critical component of successful community-based transition programs and are actively addressing challenges such as high turnover rates, shortages of direct service workers in rural areas, and language barriers between workers and MFP participants whose primary language is something other than English. One state noted a shortage of workers who have the skills set and experience to work with persons with behavioral health needs. Current efforts to address direct services worker shortages focused on Medicaid provider recruitment from existing HCBS organizations and continued education/training/certification at the local level. Ohio established a Direct Service Workforce initiative in 2012 using MFP funding and in collaboration with several state departments (Medicaid, Aging, Developmental Disabilities, Health, Mental Health & Addiction Services, Education, and Board of Regents) as well as non-governmental organizations. The initiative involves identifying core competencies for all direct service workers in the health care arena, including those in institutional settings, with the goal of increasing interest in direct service careers by building a career lattice to increase options for upward and lateral career mobility. Other state examples included developing “realistic job preview videos” for use by HCBS providers (West Virginia) and creating supply and demand projections for institutional and community workforce by town (Connecticut). In states that have implemented MLTSS, such as New Jersey, the MCOs are contractually required to establish and maintain an adequate network of providers, including HCBS providers. MCO care managers are responsible for identifying any service gaps and ensuring MCOs have adequate provider networks in place to address beneficiaries’ needs.

Twenty-three MFP states reported operating or plans to implement an MLTSS program that will include MFP participants. These initiatives include enrollment of new populations into Medicaid managed care and new or expanded use of MLTSS. While some states said it was too soon to determine the impact of managed care on MFP participants, one state noted, “making MFP part of managed care has increased our transitions…the MCO’s are better able to identify potential participants than we were able to do prior to managed care.” Still, expansion of managed care has not been seamless for individuals with complex health and LTSS needs. These systems changes require continued close coordination and introduction of new partners and new roles for coordinating and promoting community options. Five states reported challenges coordinating an MLTSS program with MFP, up from two states in 2013. Lack of access to encounter data and challenges with distribution of transition funds were examples of the challenges reported. One state acknowledged initial difficulty coordinating transition services that needed to be in place for the MFP participant on the day of discharge from the nursing facility. With the implementation of MLTSS, these services were scheduled to begin after enrollment into MLTSS and not before the transition. To address this issue, MFP participants were enrolled into MLTSS while still residing in the nursing facility and then allowed to transition any time after that. Another challenge mentioned was a result of MFP participants’ ability to change their MCO providers, which can create challenges for consistent service provision. One state with a relatively high percentage of potential MFP participants with mental illness noted the potential challenges of consistent service provision under managed care, given their ongoing challenges with mental health services capacity in the community.

MFP and Progress in LTSS Rebalancing

“We totally reorganized the transition system after looking at data reported under the MFP demonstration.” – MFP Project Director

As a result of MFP, 16 states have added transition programs to their LTSS rebalancing activities, and 27 states have used MFP to strengthen and expand existing nursing facility diversion and/or other transition programs. States with existing transition programs reported that MFP has increased the visibility of and need for such programs through improved communication, training, and marketing efforts. Federal financial support under the MFP demonstration has broadened the scale of existing transition programs, increased state staffing, and expanded HCBS availability. With the addition of MFP, states also expanded the populations of institutional beneficiaries who may be able to relocate to the community beyond those with physical disabilities to include seniors,

individuals with mental illness, and individuals with I/DD. States reported learning lessons from earlier transition initiatives and have built stronger transition mechanisms that better support specific populations. For example, North Carolina reported stronger, more consistent training in transition practices, clearer expectations related to pre- and post-transition case management activities, stronger interdisciplinary collaboration, and refined service definitions that better support the needs of individuals transitioning to the community.

“MFP created a platform for discussion, ideas, collaboration, improved data integrity, and other funding options to assist in improving LTSS rebalancing.” – MFP Project Director

States reported leveraging MFP dollars and transition experience to strengthen ongoing rebalancing efforts, including other Medicaid HCBS options. Several years after MFP was established, the ACA included a number of new and expanded LTSS options that offer states the ability to take advantage of federal funding to rebalance their delivery of LTSS toward HCBS and away from institutional care. Some of these options include the Community First Choice state plan option (CFC), BIP, the health home state plan option, and the Section 1915(i) HCBS state plan option.3 This year’s survey asked states to report on how MFP helped create new or built on existing LTSS rebalancing efforts. Most often, states reported leveraging MFP rebalancing funds and building upon infrastructure changes made with MFP to apply for and implement BIP. Similar to MFP, BIP provides a mechanism for states to earn enhanced FMAP payments (2% or 5%) through the provision of HCBS. All of the eighteen states participating in BIP are also participating in MFP. This resulted in additional staff and funding to implement a No Wrong Door/Single Entry point system, a core standardized assessment tool, and a conflict free case management system (all of which are structural requirements of BIP) as well as created inter- division/agency collaboration to improve LTSS.4 States also reported relying upon lessons learned from the implementation of MFP demonstration and supplemental services when determining which services would be covered under the CFC option, in order to continue MFP-like transition efforts when the MFP demonstration expires in 2016. In the District of Columbia, MFP has collaborated with Medicaid health home efforts on housing and mental health data, in particular relative to nursing facility residents, and, in the implementation of the Section 1915(i) HCBS state plan option for adult day health program services.

Sustainability Post-2016

While MFP has helped states make progress in LTSS rebalancing, the impending expiration of the program creates some questions about the sustainability of transition activities going forward. This year’s survey asked states what impact the expiration of MFP will have on state rebalancing efforts and the beneficiary transition experience. The MFP demonstration is set to expire at the end of FY 2016, although states have the option to request to transition MFP participants through December 2018 and to spend unused funds until 2020. Loss of enhanced federal funds for pre- and post-transition services and the loss of administrative funding for staffing were the most frequently cited concerns about MFP’s expiration. One state said its housing coordinator position would not be extended after MFP funds run out and noted that “the housing challenge will continue and [the expiration of MFP] will be a loss to the state without finding some sustainability. Housing and HCBS go absolutely hand and hand. No home to go to, no transition.” Another state feared losing the expertise of outreach specialists unless it can find another source of funding for those positions. States operating MLTSS programs were hopeful the expiration of MFP would have little impact on transition efforts since most of the MFP transition services are available through managed care. Going forward, these states are looking for transitions to continue with the assistance of the MCOs. States also noted that other Medicaid and/or state-funded transition initiatives that operate concurrently with MFP would continue after MFP expires.

“MFP has been an active catalyst for pushing culture change for the nursing home population – pushing for and allowing more consumer autonomy and choice.” – MFP Project Director

At the time of this survey, all states were in the sustainability planning process to determine existing authorities through which transition services or activities could be continued post-MFP. To minimize the impact of the expiration of the demonstration on rebalancing efforts and beneficiary transition experience, CMS required states to submit an MFP sustainability plan by April 30, 2015. The sustainability plans were developed to maintain transition efforts from CY 2016 through CY 2020 and beyond. Approval of such plans was expected in August 2015. A number of states reported plans to add key demonstration services to their Section 1915(c) waivers, as well as to the CFC option, in order to continue transitions when MFP expires (although states also noted that some demonstration services would be terminated when MFP expires). Specifically, states mentioned ensuring the continuity of transition coordination services or transition management services. Additionally, states were hopeful that they could sustain MFP staff positions through their legislative process; however, all future funding commitments are subject to administration and budgetary priorities once MFP funding ends.