Modern Era Medicaid: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2015

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Recognizing the limited family budgets of low-income individuals, federal rules set parameters in Medicaid and CHIP on the amount of premiums and cost-sharing, such as copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles, that states may charge (see Box 1). Consistent with federal rules, the findings presented below show that premiums and cost-sharing for selected services generally remain low in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 1, 2015. Even with flexibility to charge premiums and cost-sharing, many states limit charges in their programs to minimize barriers for enrollees in accessing care and reduce administrative burdens and complexities for state agencies.

Box 1: Premium and Cost-Sharing Rules for Medicaid and CHIP

The ACA did not make direct changes to premium and cost-sharing rules for Medicaid and CHIP, but its adjustments to eligibility thresholds impacted how some states assess premiums and cost-sharing. Specifically, the ACA’s establishment of a minimum threshold for children’s Medicaid eligibility at 138 percent of the FPL effectively raised the income level at which premiums and cost-sharing start in some states. All children, regardless of age, with family incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the FPL now fall under Medicaid’s premium and cost-sharing protections. As a result, the income threshold above which premiums begin for children increased to 138 percent of the FPL in seven states. Similarly, changes in eligibility thresholds resulted in an increase in the income level at which cost-sharing begins in 14 states that charge cost-sharing in CHIP but not Medicaid. Other states adjusted the income level at which cost-sharing begins to align with their MAGI-converted eligibility thresholds.2

Premiums

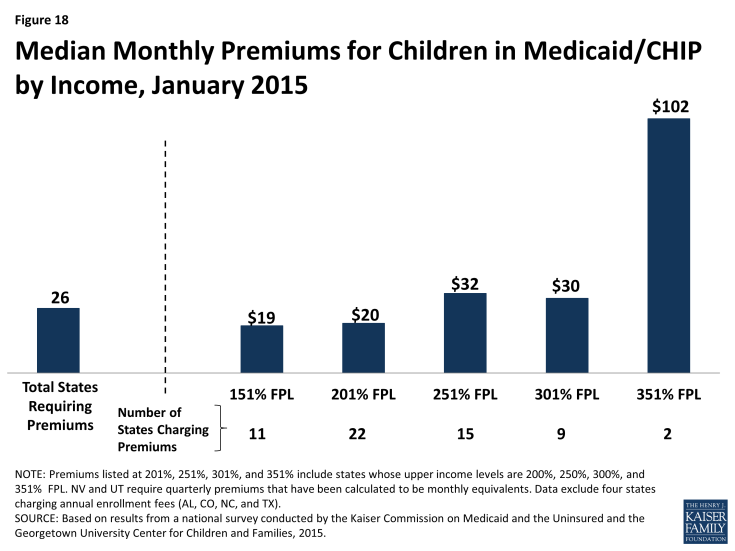

Overall, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid or CHIP. This total includes three states (CA, MD and VT) that charge premiums for children in Medicaid with incomes above 150 percent of the FPL, 23 states that charge monthly or quarterly premiums in their CHIP programs, and four states that charge annual enrollment fees in CHIP. The greater prevalence of premiums and enrollment fees in CHIP reflects the relatively higher family incomes of children covered by the program as well as its more flexible premium rules. Among the 26 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums for children in Medicaid or CHIP, most (21) limit the charges to children in families with incomes at or above 150 percent of the FPL, including eight that only assess the charges at income levels at or above 200 percent of the FPL. Median premium amounts per child range from $19 at 151 percent of the FPL to $102 at 351 percent of the FPL, although only two states provide coverage at this income level (Figure 18). The ACA protects children’s coverage through 2019, and, thus, premium increases are permitted only if specific methods for raising premiums were approved in the state Medicaid or CHIP plan as of March 23, 2010.

There is variation across states in policies related to non-payment of premiums.3 If states charge premiums in Medicaid, they must offer a 60-day grace period before coverage can be cancelled for nonpayment. While unpaid premiums may result in termination of Medicaid coverage, states cannot require enrollees to repay premiums as a condition for re-enrollment, nor can they prevent eligible individuals from re-enrolling immediately. In CHIP, states are required to offer a minimum grace period of 30 days. Grace periods vary across the 23 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums in CHIP, with seven states providing the minimum 30-day grace period and 17 states providing grace periods of 60 days or longer. Following cancellations of coverage for nonpayment of premiums, states may delay re-enrolling former enrollees in CHIP coverage, but the ACA limits such lock-out periods to no more than 90 days. As of January 1, 2015, 13 of 23 states that charge monthly or quarterly premiums in their separate CHIP programs have lock-out periods. This count reflects newly established lock-out periods in eight states (IN, KS, LA, MA, NV, UT, VT and WA) and the elimination of lock-out periods in four states (CT, IL, OR, and WV) since January 2013. Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin also reduced their lock out periods for non-payment of premiums from six months to 90 days. In 16 states, families who have been dis-enrolled due to non-payment of premiums must reapply to re-enroll in coverage. Eight states allow families to receive retroactive coverage if they pay outstanding premiums.

In general, states do not charge low-income parents and other adults premiums in Medicaid. This reflects the fact that eligibility for parents and other adults is generally limited to levels below which premiums can be charged. However, four states (AR, IA, MI, and PA) have received Section 1115 waiver approval to impose monthly payments that are not otherwise permitted under federal rules for some adults covered through their Medicaid expansions. As of January 1, 2015, these payments had been implemented in Iowa and Michigan. Although the specific policies vary across the four states, payment of these monthly contributions is not always a condition of enrollment, and, in some cases, individuals do not have to make the payments if they participate in certain activities or obtain an exemption.

Cost-Sharing

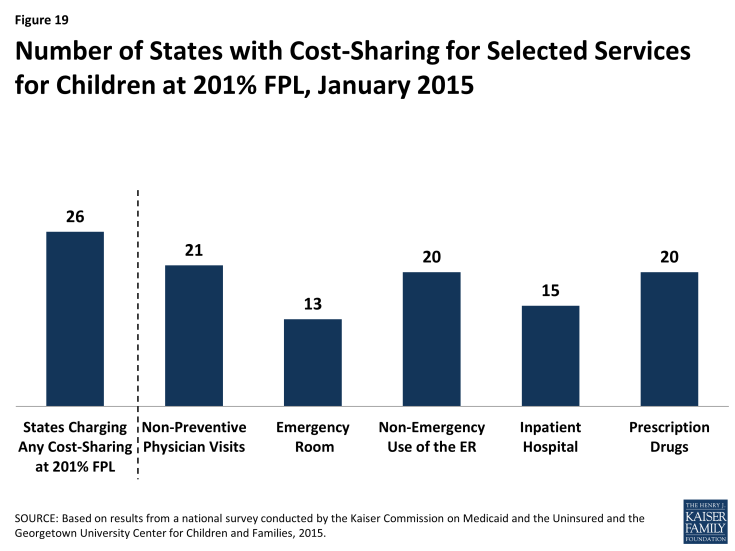

Overall 26 states charge cost-sharing for children in Medicaid or CHIP. Four states charge cost-sharing for children in Medicaid, while 24 of 36 states with separate CHIP programs charge cost-sharing, although cost-sharing requirements vary by income. Cost-sharing for children begins at or above 133 percent of the FPL in all of these states, except Tennessee, which assesses cost-sharing at lower income levels under Section 1115 waiver authority. Cost-sharing also varies by service type. For example, for a child with family income at 201 percent of the FPL, 21 states charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 13 charge for an emergency room visit, 20 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 15 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 20 have charges for prescription drugs, although, in some cases, charges only apply to brand name or non-preferred brand name drugs (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Number of States with Cost-Sharing for Selected Services for Children at 201% FPL, January 2015

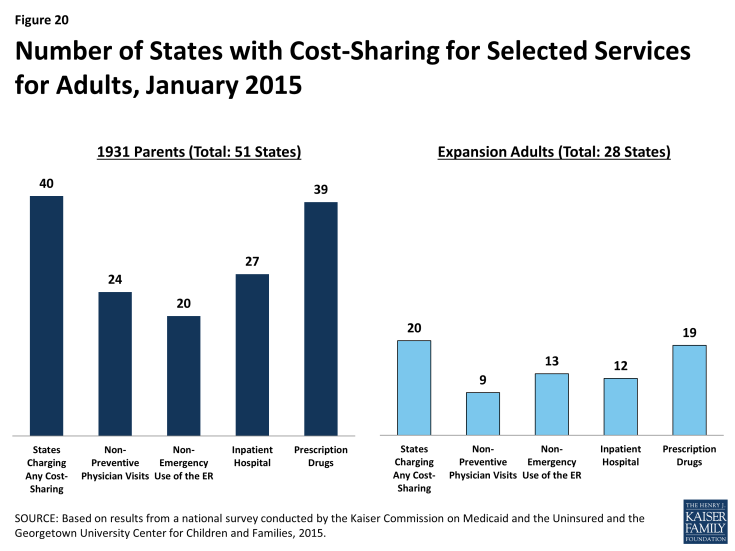

Most states (40) charge cost-sharing for Section 1931 parents in Medicaid and 20 of the 28 states that have expanded Medicaid have cost-sharing for expansion adults (Figure 20). Reflecting the low incomes of parents and adults covered by Medicaid, this cost-sharing is generally limited to nominal amounts. For parents, 24 states charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 20 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 27 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 39 charge for prescription drugs, although, in some cases, the charges only apply to brand name drugs. Among the 28 states with coverage for Medicaid expansion adults, 9 charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 13 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 12 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 19 charge for prescription drugs.