Mental Health and Substance Use Considerations Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, children have experienced major disruptions as a result of public health safety measures, including school closures, social isolation, financial hardships, and gaps in health care access. Many parents have reported poor mental health outcomes in their children throughout the pandemic – in May 2020, shortly after the pandemic began, 29% said their child’s mental or emotional health was already harmed; more recent research from October 2020 showed that 31% of parents said their child’s mental or emotional health was worse than before the pandemic. Some children have also exhibited increased irritability, clinginess, and fear, and have had issues with sleeping and poor appetite. As mental health issues become more pronounced among children, access to care issues may also be increasing. These access issues may exacerbate existing mental health issues among children.

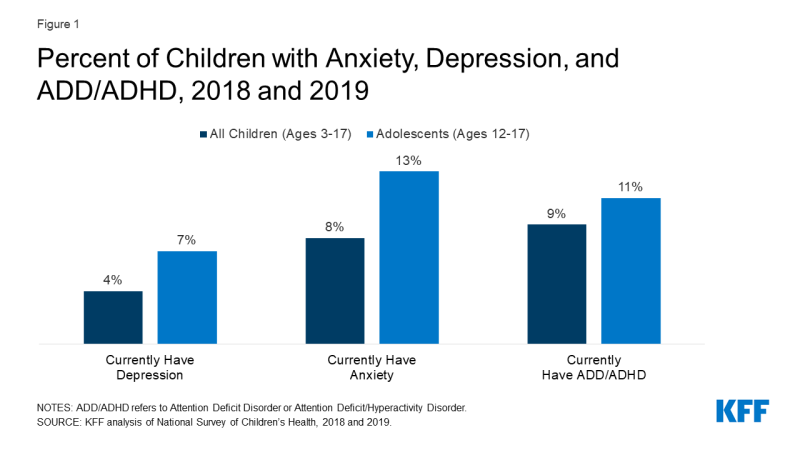

Even before the pandemic, many children in the United States were living with mental health disorders. On average, in the years 2018 and 2019, among children ages 3-17, 8% (5.2 million) had anxiety disorder, 4% (2.3 million) had depressive disorder, and 9% (5.3 million) had attention deficit disorder or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD) (Figure 1). Other mental health disorders among children and adolescents include obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and eating disorders. Adolescents in particular have seen increases in poor mental health outcomes in recent years, such as persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness and suicidal thoughts. Many mental health conditions develop by adolescence and, if unaddressed, can persist into adulthood and limit quality of life.

This brief explores factors contributing to poor mental health and substance use outcomes among children during the pandemic, highlighting groups of children who are particularly at risk and barriers to accessing child and adolescent mental health care. Although data on child and adolescent mental health have historically been limited, where possible, we draw upon data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in addition to surveys conducted during the pandemic. Key takeaways include:

- Several pandemic-related factors may negatively impact children’s mental health. Social distancing and stay-at-home orders could lead to loneliness and isolation among children – known risk factors for poor mental health. Income insecurity and poor mental health experienced by parents during the pandemic may also adversely affect children’s mental health and may be associated with a possible rise in child abuse.

- Adolescents, young children, LGBTQ youth, and children of color may be particularly vulnerable to negative mental health consequences of the pandemic. During the pandemic, more than 25% of high school students reported worsened emotional and cognitive health; and more than 20% of parents with children ages 5-12 reported their children experienced worsened mental or emotional health. A survey of LGBTQ youth found that many LGBTQ adolescent respondents (ages 13-17) reported symptoms of anxiety (73%) and depression (67%) and serious thoughts of suicide (48%) during the pandemic. Although data is limited on children of color, research suggests that even before the pandemic they had higher rates of mental illness, but were less likely to access care.

- Prior to the pandemic, many children with mental health needs were not receiving care; and it is possible that access to mental health services has since worsened. Data shows that there have been large declines in pediatric mental health care utilization since the pandemic began. Access to mental health care via telehealth has increased, however, access via schools – a commonly utilized site of care for children and adolescents – may have decreased due to school closures.

- Several bills that include funding related to children’s mental health have been introduced during the pandemic. The recently passed American Rescue Plan Act allocates funding for pediatric mental health care access and youth suicide prevention. The American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan propose additional funding for services to benefit children, including upgraded schools and nutrition programs.

Factors Contributing to Poor Mental Health Among Children During the Pandemic

Children’s mental health during the pandemic may be negatively affected by social distancing and stay-at-home orders, which could lead to loneliness and isolation – known risk factors for poor mental health outcomes. Nearly a quarter of high school students report feeling disconnected from their classmates during the pandemic. Research has broadly shown that loneliness is associated with anxiety and depression among children. Additionally, the duration of a child’s experience of loneliness is linked to mental health problems later in life. Pandemic-related isolation and quarantines may also lead to some children experiencing separation anxiety from their parents or caregivers and fear of themselves or family members becoming infected.

Many parents are experiencing stress and poor mental health during the pandemic. This may be due to a number of factors, including parents balancing both work and childcare, and parents facing income insecurity (49% of households with children reported a loss of employment income and 61% reported difficulty paying for usual household expenses in late March 2021). The poor mental health of parents may adversely affect children’s mental health. Additionally, children in low-income households are at greater risk for mental health issues and are less likely to have access to needed mental health care, compared to children in high-income households.

Media reports suggest child abuse may have increased in light of the pandemic, although it is unclear based on available data. The pandemic’s negative impact on parents’ mental health and stress may be associated with the possible rise in child abuse. Child abuse can lead to immediate emotional and psychological problems and is also an adverse childhood experience (ACE) linked to possible mental illness and substance misuse later in life. Reports of child abuse have dropped since school closures began, and child abuse-related emergency department (ED) visits have decreased throughout the pandemic. However, the severity of injuries among these ED visits has increased and resulted in more hospitalizations; and it is possible that due to school closures and stay-at-home orders during the pandemic, many cases are going undetected, since educators play a primary role in identifying and reporting child abuse. Research has also found that cases of child abuse increased during the previous recession.

Special Mental Health Considerations for Adolescents and Children

Research during and leading up to the pandemic suggests that adolescents, young children, LGBTQ youth, and children of color may be particularly vulnerable to negative mental health consequences of the pandemic, including anxiety and depression.

Adolescents

Throughout the pandemic, data has shown that adolescents have experienced poor mental health outcomes. Shortly after the pandemic began, more than 25% of high school students reported worsened emotional and cognitive health. A more recent survey of high school students found that only one-third felt they were able to cope with their sources of stress, which include strained mental health and peer relationships. Private insurance data also shows that while all health care claims for adolescents ages 13-18 were down in 2020 compared to 2019, mental health-related claims for this age group increased sharply.1 The most frequently diagnosed mental health conditions in 2020 were depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder. Even before the pandemic, 7% (1.8 million) of high school students had depression and 13% (3.1 million) had anxiety (Figure 1).

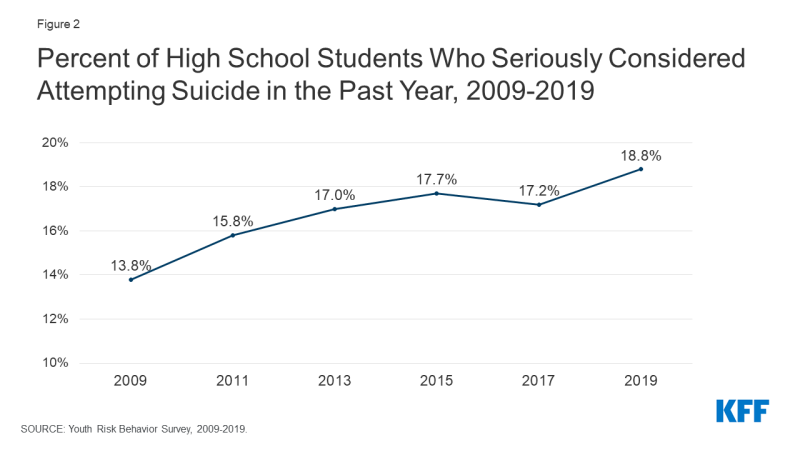

It is unclear whether suicidal ideation and suicides have increased among adolescents; however, media reports and a study of a pediatric emergency department suggests they may have in light of the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, serious thoughts of suicide were already on the rise among high school students (from 14% in 2009 to 19% in 2019, Figure 2). Suicide was also the second leading cause of death among adolescents (ages 12-17) in 2019, resulting in 1,580 deaths.2

Figure 2: Percent of High School Students Who Seriously Considered Attempting Suicide in the Past Year, 2009-2019

Some evidence also shows that substance use disorders and overdoses among adolescents are increasing during the pandemic. Solitary substance use, as opposed to social substance use, has increased among adolescents during the pandemic. An analysis of private insurance data found that, in general, claims for substance use disorders and overdoses increased as a share of all medical claims for adolescents ages 13 to 18 in 2020, compared to 2019.1 Prior to the pandemic, 1.1 million adolescents reported having a substance use disorder in the past year. When substance use begins at younger ages, it is more likely to persist into adulthood and increase the risk of addiction.

Young children

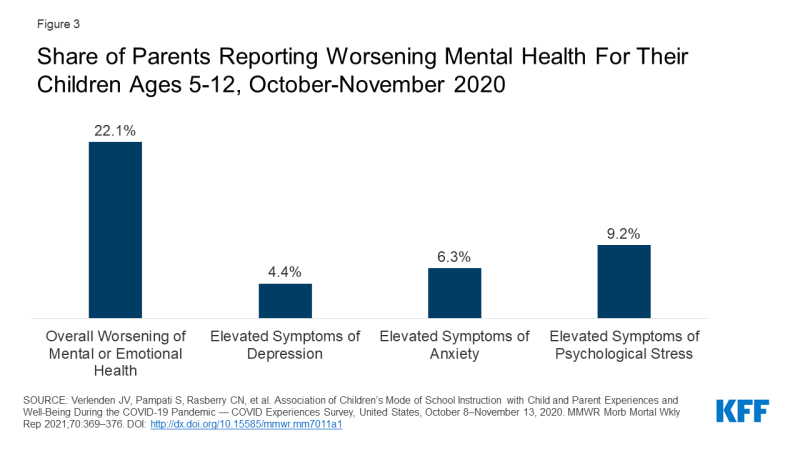

During the pandemic, parents have reported that young children experienced worsened mental health outcomes. Young children may be experiencing worsened mental health due to pandemic-related disruptions in their routine and caregiving or stressful home environments. Forty-seven percent of parents with children who are not yet school-age reported they are more worried about their children’s social development than they were before the pandemic. During the pandemic, parents with children ages 5-12 reported their children showed elevated symptoms of depression (4%), anxiety (6%), and psychological stress (9%); and experienced overall worsened mental or emotional health (22%) (Figure 3). Parents of children attending school virtually were more likely to report their children experienced overall worsened mental or emotional health than parents of children attending school in-person (25% vs. 16%, respectively).

Figure 3: Share of Parents Reporting Worsening Mental Health For Their Children Ages 5-12, October-November 2020

An analysis of private insurance data found that claims for OCD and tic disorders increased as a share of all medical claims for children ages 6 to 12 in 2020, compared to 2019.1 ADHD was the top mental health diagnosis for children ages 6 to 12 during 2020; however, claims for ADHD decreased as a share of all medical claims, compared to 2019. This decrease may be due to teachers being unable to observe possible signs of ADHD as they typically would during in-person instruction.

LGBTQ YOUTH

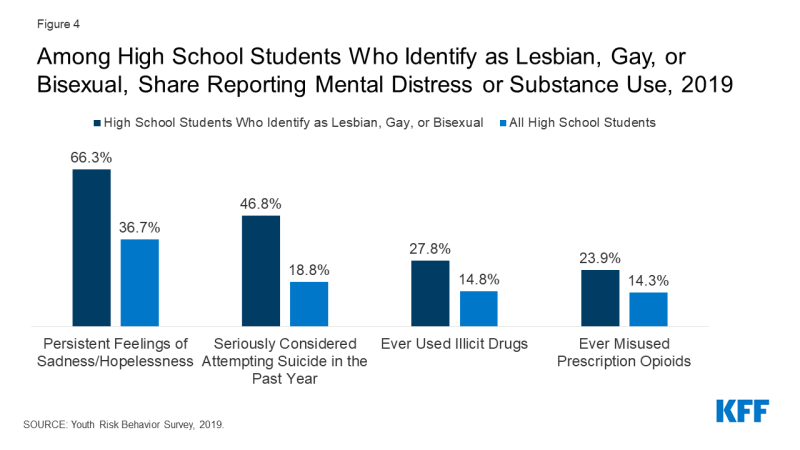

Research suggests that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) youth may be particularly vulnerable to negative mental health outcomes during the pandemic. A non-probability survey of LGBTQ youth conducted in Fall 2020 found that large shares of adolescent respondents (ages 13-17) reported symptoms of anxiety (73%) or depressive (67%) disorder in the past two weeks; and 48% seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year. Prior to the pandemic, LGBTQ youth were already at increased risk for depression, suicidal ideation, and substance use. In 2019, 66% of lesbian, gay, and bisexual high schools students reported persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness (compared to 37% of all high school students) and 47% reported serious thoughts of suicide (compared to 19% of all high school students) (Figure 4). Larger than average shares of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth also reported substance use before the pandemic.

Figure 4: Among High School Students Who Identify as Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual, Share Reporting Mental Distress or Substance Use, 2019

Children of color

Poor mental health outcomes resulting from the pandemic may disproportionately affect children of color. Prior to the pandemic, children of color had higher rates of mental illness, but were less likely to receive care. They were also less likely than White children to have access to school health services, including mental health care. During the pandemic, these access issues may be further exacerbated as school services may have been suspended or limited. Asian children may also be uniquely at risk of adverse mental health outcomes due to anti-Asian racism that has emerged during the pandemic; prior to the pandemic, they were more likely to face barriers to accessing mental health services than White children. Structural racism has been associated with poor mental health outcomes. During the pandemic, Black and Latino adults have also experienced higher rates of illness and death from COVID-19, negative financial impacts, and poor mental health outcomes, which may have adverse mental health effects on children from these communities.

Suicide may also disproportionately affect children of color. Before the pandemic, Native American adolescent girls were three times more likely to die of suicide than White adolescent girls, and suicide rates have been increasing faster among Black children and teens than among non-Black children and teens.

Access to Children’s Mental Health Care During the Pandemic

Prior to the pandemic, many children with mental health needs were not receiving care for reasons including costs, lack of providers, and limited insurance coverage. In 2019, 11% of children ages 3-17 received mental health care in the past year. However, only one in five children with mental, emotional, or behavioral disorders were receiving mental health care from a specialized provider. It is possible that access to mental health care – like access to all health services – worsened during the pandemic. In an effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus, many health care providers changed the way they deliver services, sometimes suspending them or operating at limited capacity. Telehealth use has increased for many types of health services, but not necessarily by enough to offset the drop in in-person care.

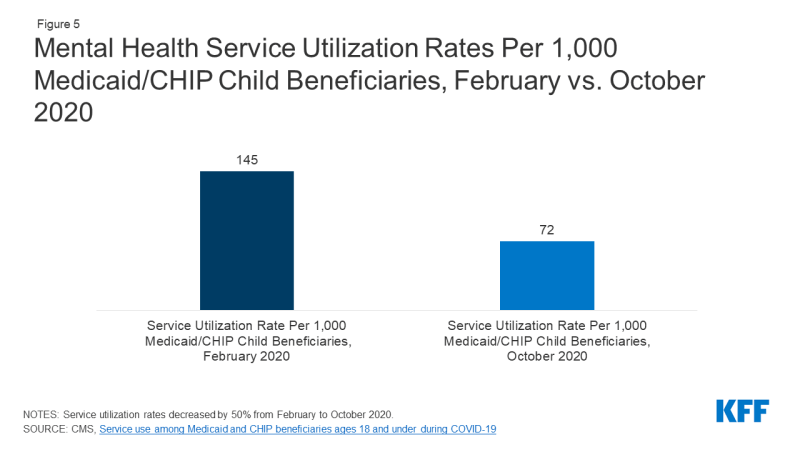

A small share of parents also reported delaying mental health care (4%) or treatment for alcohol or drug use (2%) for their children in September 2020 in order to reduce exposure to COVID-19 or in light of limited provider services. However, other data suggests there have been large declines in pediatric mental health care utilization. Among Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) beneficiaries under the age of 18, the number of children receiving mental health services dropped by 50% from February to October 2020 (Figure 5). While utilization rates of other services – including child screening and dental services – among Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries under the age of 18 eventually began to rebound during this time period, mental health service utilization rates lagged in comparison. Nearly two out of five children under the age of 18 in the U.S. are Medicaid or CHIP beneficiaries. Private mental health care claims also decreased from 2019 to 2020.1 Despite a drop in the total number of mental health claims among privately insured patients, mental health care represented a larger share of total medical claims among these patients in 2020 than in 2019.

Figure 5: Mental Health Service Utilization Rates Per 1,000 Medicaid/CHIP Child Beneficiaries, February vs. October 2020

Throughout the pandemic, many insurers and mental health care providers have expanded telehealth services during the pandemic. Claims data from CMS show a significant increase in the utilization of outpatient mental health services via telehealth for Medicaid/CHIP child beneficiaries beginning in March 2020, with a peak in April. By July 2020 (the latest telehealth data for mental health services available at the time of this publication), the use of telehealth for mental health services decreased, but remained above pre-pandemic utilization levels. Analysis of pediatric private claims data has shown a similar trend.1 Additionally, a number of barriers may limit some children’s access to mental health care via telehealth during the pandemic, including lack of access to digital devices, internet, and privacy in speaking with a provider.

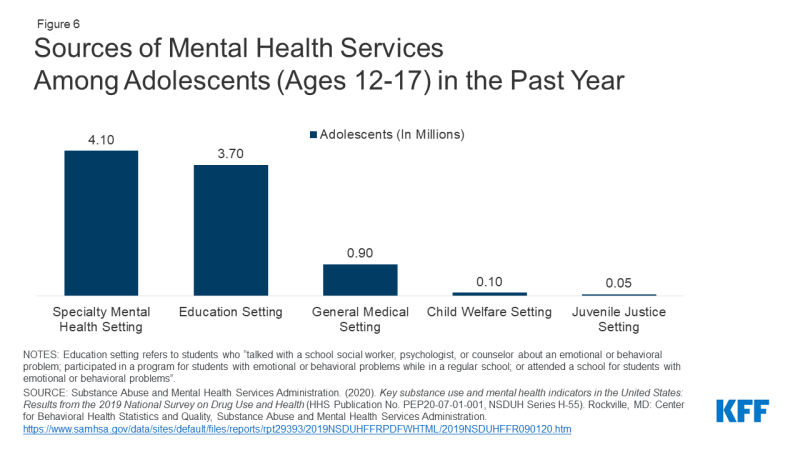

With pandemic-related school closures, children and adolescents may have faced limited or suspended health services they commonly access through school-based health centers (SBHCs), including mental health services. In focus groups conducted during the pandemic, many SBHC staff reported challenges delivering health care and heightened concerns around mental distress among students, including symptoms of anxiety and depression and suicidal ideation. Prior to the pandemic, many adolescents sought mental health care through schools (3.7 million adolescent visits in 2019, Figure 6).

Anecdotal evidence from numerous media reports suggests that the availability of psychiatric beds in hospitals and mental health facilities has decreased during the pandemic, exacerbating an existing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatric beds, which are needed for individuals seeking emergency care during a mental health crisis. Surges of patients with severe COVID-19 have, at times, left hospitals at or above admissions capacity, and some have repurposed psychiatric beds for COVID-19 patients or have limited admissions in order to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus. Some financially hard-hit hospitals have closed inpatient psychiatric units entirely. It is possible that children in need of hospitalization for mental health disorders during the pandemic have challenges finding hospitals with enough capacity.

Policy Responses

Stimulus bills passed during the course of the pandemic have included direct financial support for families with children, as well as other provisions that may alleviate some of the mental health burdens children and adolescents face. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which was signed into law on March 12, 2021, builds on prior pandemic aid by providing financial support to many families with children. It also allocates funding for mental health and substance use disorder services, with a portion designated specifically for children’s mental health, including $80 million for pediatric mental health care access, $20 million for youth suicide prevention, and $10 million for the National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative. The ARPA also designates funding for school, child care, and nutrition programs that serve many children and adolescents; provides relief fund payments for rural Medicaid and CHIP providers; and newly offers federal support to states for community-based mobile crisis intervention services. The recently proposed American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan outline additional funding for services to benefit children, including free preschool, new and upgraded public schools and childcare facilities, and nutrition programs.

Bipartisan bills aimed at addressing mental health and substance use consequences from the pandemic were recently introduced. Several of these bills at both the national and state level specifically focus on children. The COVID-19 Mental Health Research Act proposes research on pandemic-related mental health impacts, including impacts on children and adolescents. In Colorado, the Rapid Mental Health Response For Colorado Youth bill would establish a temporary program allowing youth to access mental health and substance use disorder services for free or reduced costs.

Looking ahead, poor mental health outcomes and access to care issues among children and adolescents are likely to persist beyond the pandemic. The pandemic may also increase the risk of children having adverse childhood experiences, such as experiencing violence or being exposed to adult substance misuse, which can lead to long-term mental health and substance use issues. This brief highlights the need for policymakers, providers, educators, parents, and researchers to consider the ways the COVID-19 pandemic may impact children’s mental health for the long-term.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.