Medicare Part D in Its Ninth Year: The 2014 Marketplace and Key Trends, 2006-2014

Jack Hoadley, Laura Summer, Elizabeth Hargrave, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman

Published:

Executive Summary

Since 2006, Medicare beneficiaries have had access through Medicare Part D to prescription drug coverage offered by private plans, either stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MA-PD plans). Now in its ninth year, Part D has evolved due to changes in the private plan marketplace and the laws and regulations that govern the program. This report presents findings from an analysis of the Medicare Part D marketplace in 2014 and changes in features of the drug benefit offered by Part D plans since 2006.

Part D Highlights for 2014 and 2006-2014 Trends

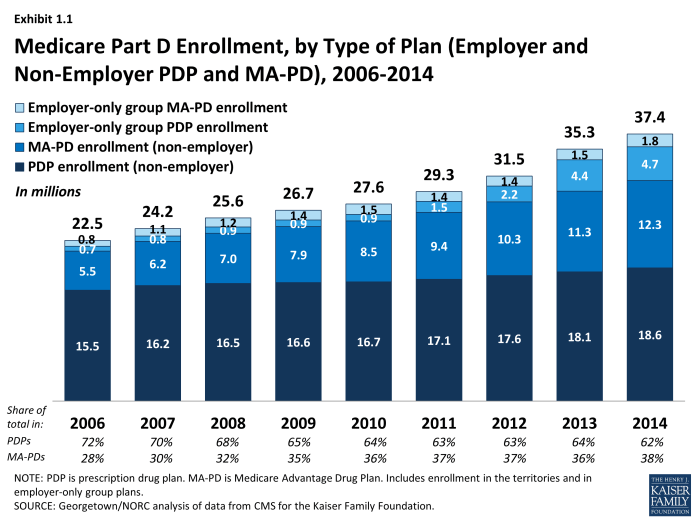

In 2014, more than 37 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare drug plans, an increase of 2 million compared to 2013 and 15 million since 2006.

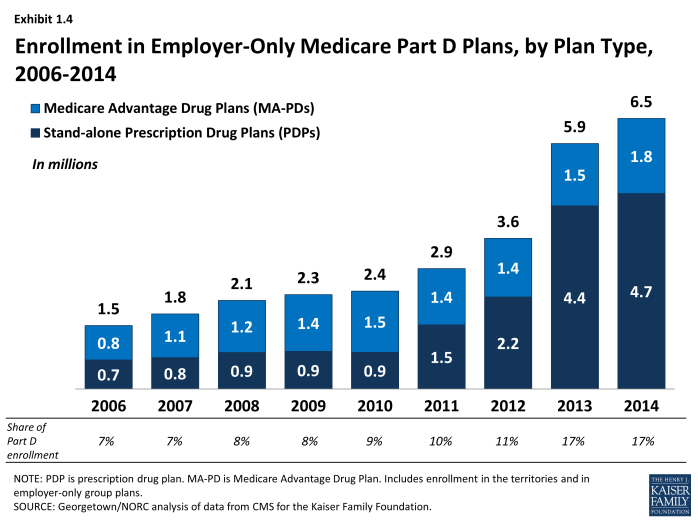

- The majority (62 percent) of Part D enrollees are in PDPs, but enrollment in MA-PD plans is growing more rapidly, representing half of the net increase in enrollment from 2013 to 2014. About 6.5 million Medicare beneficiaries with drug coverage from their former employers now get that coverage through a Part D plan designed solely for that firm’s retirees. Partly due to changes in law that took effect in 2013, enrollment in employer plans has quadrupled since 2006.

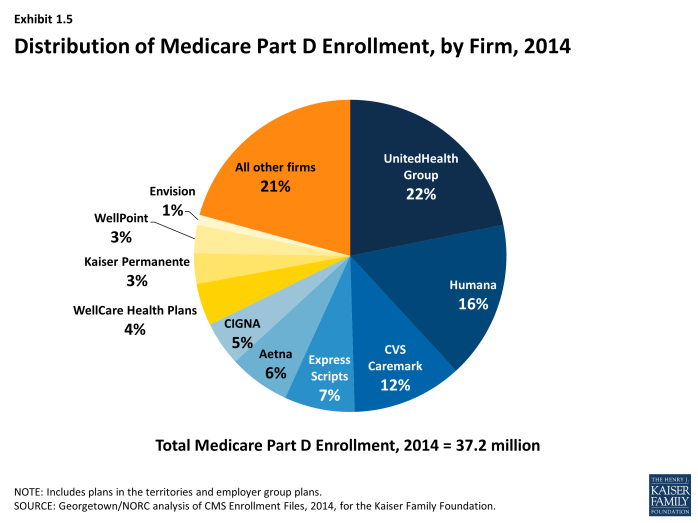

In 2014, three Part D sponsors account for half of all Part D PDP and MA-PD enrollees.

- UnitedHealth, Humana, and CVS Caremark have enrolled half of all participants in Part D. This level of market concentration is relatively unchanged since 2006. UnitedHealth and Humana have held the highest shares of enrollment since the program began, while enrollment in CVS Caremark has grown through the acquisition of other plan sponsors. UnitedHealth, by itself, has maintained the top position for all nine years of the program, and in 2014 provides coverage to more than one in five PDP and MA-PD enrollees.

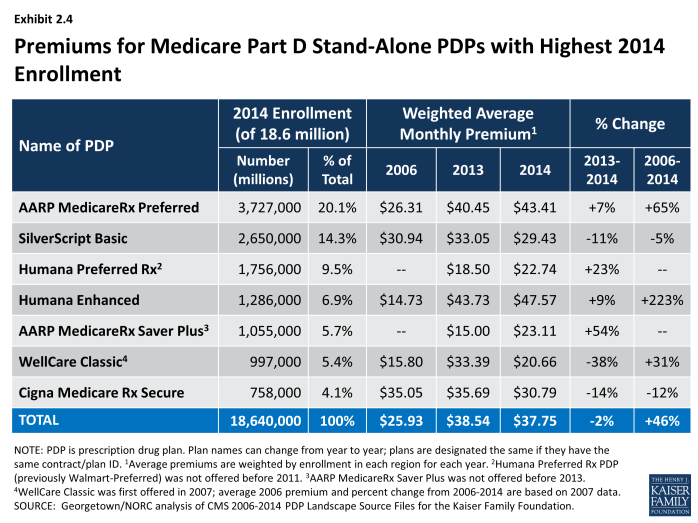

Average monthly PDP premiums have been essentially flat since 2010; premiums for some of the most popular plans increased for 2014, while for other popular plans premiums fell.

- On average, PDP enrollees pay premiums of $37.75 per month in 2014. PDP premiums vary widely even for plans with equivalent benefits, ranging from $12.80 to $111.40 per month for plans offering the basic Part D benefit. UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP, which was new in 2013, raised its premiums by 54 percent (an average increase of about $8 per month) in 2014. By contrast, WellCare’s Classic PDP lowered its premium by 38 percent (an average decrease of about $13 per month) in 2014.

- Part D enrollees in MA-PD plans pay lower premiums on average ($14.70) than those in PDPs.

Cost sharing for brand-name drugs has been relatively stable in recent years, but has risen substantially since the start of Part D; MA-PD plan enrollees generally pay somewhat higher cost sharing than PDP enrollees.

- Cost sharing for brands between 2006 and 2014 has increased by about 50 percent for beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs and by about 70 percent for those in MA-PD plans. Copayments for brand-name drugs are higher than those typically charged by large employer plans, while copayments for generics are generally lower.

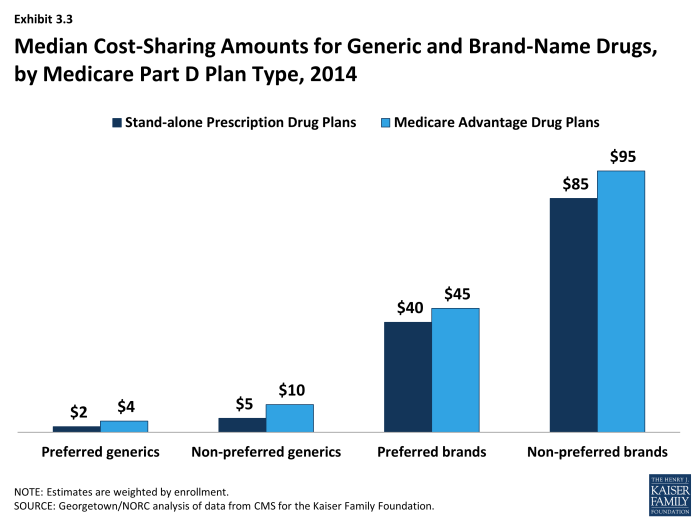

- On average, MA-PD plan enrollees pay somewhat higher cost sharing for their drugs than PDP enrollees, particularly for brand-name drugs. For example, median cost sharing for preferred and non-preferred brands in MA-PD plans is $45 and $95, respectively, compared to $40 and $85 in PDPs.

In 2014, about three-fourths of all plans (76 percent of PDPs and 75 percent of MA-PD plans) use five cost-sharing tiers: preferred and non-preferred tiers for generic drugs, preferred and non-preferred tiers for brand drugs, and a tier for specialty drugs.

- Four-tier arrangements were most common until 2012 when plans began shifting toward the five-tier cost-sharing design.

Part D plans typically use specialty tiers for high-cost drugs and charge coinsurance of from 25 percent to 33 percent during the benefit’s initial coverage period, as in previous years.

- These initial high out-of-pocket costs may create a financial barrier to starting use of specialty drugs, which are expected to be a significant cost driver for Medicare in the future. Users who incur these initial high out-of-pocket costs are likely to reach the benefit’s catastrophic threshold within a short period and thus see their coinsurance reduced to 5 percent.

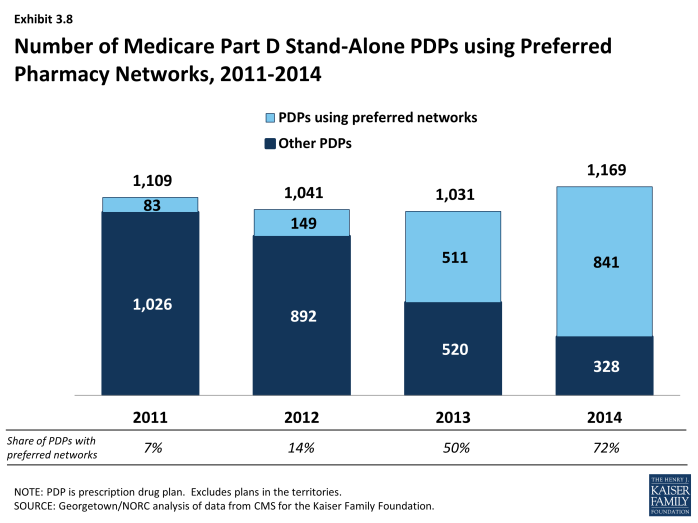

Use of preferred pharmacy networks has grown rapidly in recent years, and for some PDP enrollees, access to preferred pharmacies is geographically limited.

- The share of Part D stand-alone drug plans with this type of pharmacy network grew from 7 percent in 2011 to 72 percent in 2014. Enrollees in these plans pay lower cost sharing if they use preferred pharmacies and higher cost-sharing if they use a non-preferred pharmacy. In some plans, however, there is no preferred pharmacy within a reasonable travel distance, which could make it difficult for enrollees in these plans to take advantage of this lower cost sharing.

About one in six LIS beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs (1.3 million beneficiaries) are paying a premium for their Part D plan in 2014.

- About 11 million Part D enrollees receive extra help through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), a majority of whom (8 million) are enrolled in stand-alone PDPs. The subsidy reduces cost sharing and pays their drug plan premiums, as long as they enroll in PDPs designated as benchmark plans. But 16 percent of LIS beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs (1.3 million) are paying monthly premiums in 2014, and of this group, two-thirds are paying $10 or more per month. In addition, 300,000 LIS beneficiaries enrolled in MA-PD plans (19 percent) are paying premiums in 2014. CMS does not reassign these beneficiaries to a zero-premium PDP because they have actively selected the plan they are in. On average, LIS beneficiaries paying premiums for their PDPs pay $17.85 per month, well above the average in previous years.

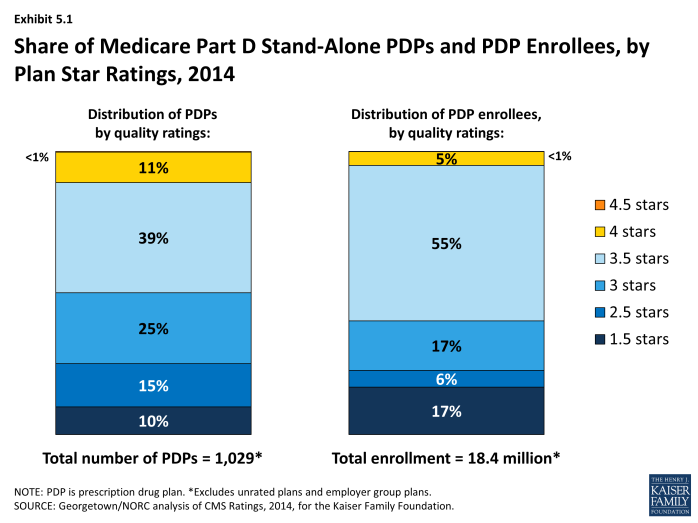

Only 5 percent of PDP enrollees are in plans with the highest star ratings (4 stars or more).

- More than half of all PDP enrollees are in plans with 3.5 stars out of a maximum five stars. Nearly one-fourth of PDP enrollees are in plans with fewer than 3 stars; plans at this level for three years in a row are subject to removal from the program.

While the Part D program has matured since 2006, the marketplace also changes every year. Plans can and do enter and drop out of the market annually, and enrollees can and do experience changes in premiums, cost sharing for their medications, which drugs are covered by their plan, and which pharmacies they can use without paying higher cost sharing. Now in its ninth year of operation, the Part D program has enjoyed relative stability in recent years. The program has had consistently high levels of plan participation, offering dozens of plan choices for beneficiaries in each region and broad access to generic and brand-name drugs.

Beneath the surface, however, there are some sobering trends. This analysis highlights the cost and access trends that could pose challenges for Part D enrollees. Although premiums have been flat for several years, average premiums have increased by nearly 50 percent between 2006 and 2014. In addition, median cost sharing for brand-name drugs has increased over these years. Finally, many low-income beneficiaries are paying steadily higher premiums for coverage when they could be enrolled in premium-free plans.

Introduction

Since 2006, Medicare beneficiaries have had access to prescription drug coverage offered by private plans, either stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MA-PD plans). These Medicare drug plans (also referred to as Part D plans) receive payments from the government to provide Medicare-subsidized drug coverage to enrolled beneficiaries. Part D plans are required to offer a defined standard benefit or one that is equal in value (Exhibit I.1). They may also offer an enhanced benefit. Medicare drug plans must meet defined requirements, but may vary in terms of premiums, benefit design, gap coverage, formularies, and utilization management rules.

In 2014, more than 37 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare drug plans, including 23 million in PDPs and 14 million in MA-PD plans.1, 2 About 11 million Part D enrollees are receiving extra help through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program to pay their drug plan premiums and cost sharing. Part D has evolved since its inception in 2006 due to changes in the private plan marketplace and the regulations that govern the program. The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) is bringing significant improvements to the program, primarily phasing out the coverage gap, or “doughnut hole,” in the drug benefit.3 In addition to a 50 percent manufacturer discount on the price of brand-name drugs in the gap, the law further reduces cost sharing for brand-name and generic drugs in the gap over time, reducing cost sharing to the level that applies before the gap and eliminating the coverage gap in 2020. In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has implemented other statutory and regulatory changes that have resulted in some consolidation of Part D plan offerings, along with a degree of greater standardization.

This report presents findings from an analysis of the Medicare Part D marketplace in 2014, the program’s ninth year, and changes in various features of the drug benefit since 2006.4 It presents key findings in five different areas:

- Enrollment and plan availability;

- Premiums;

- The design of Part D benefits, including cost sharing, specialty tiers, formularies, utilization management, the coverage gap, and preferred pharmacy networks;

- The Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program for low-income beneficiaries; and

- Plan performance ratings.

The findings are based on data from CMS for all plans participating in Part D. More detail about the methods used in this analysis is provided on page 44.

Key Findings

Section 1: Part D Enrollment and Plan Availability

Beneficiary Participation in Part D

More than 37 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a Part D plan, either a PDP or MA-PD in 2014, representing 70 percent of all eligible Medicare beneficiaries. This is an increase of 2 million beneficiaries since 2013 and of 15 million beneficiaries since 2006 when only 53 percent of eligible beneficiaries were enrolled (Exhibit 1.1). About half of this increase comes from additional enrollment in MA-PD plans, which is likely a mix of enrollees new to Part D and those who switched from PDPs to MA-PD plans. About one-fourth of the increase in 2014 is higher PDP enrollment, and another one-fourth is enrollment in employer-only Part D plans.

The 5.5 percent enrollment increase from 2013 to 2014 is lower than the average annual increase of 6.5 percent since the program’s start in 2006. Above-average growth in the two previous years was mainly a result of increased enrollment of retirees in employer-only Part D plans.1 Although many beneficiaries who are not enrolled in Part D plans have drug coverage from former employers or some other type of coverage equivalent to Part D, about 12 percent of Medicare beneficiaries are estimated to have no drug coverage whatsoever.2

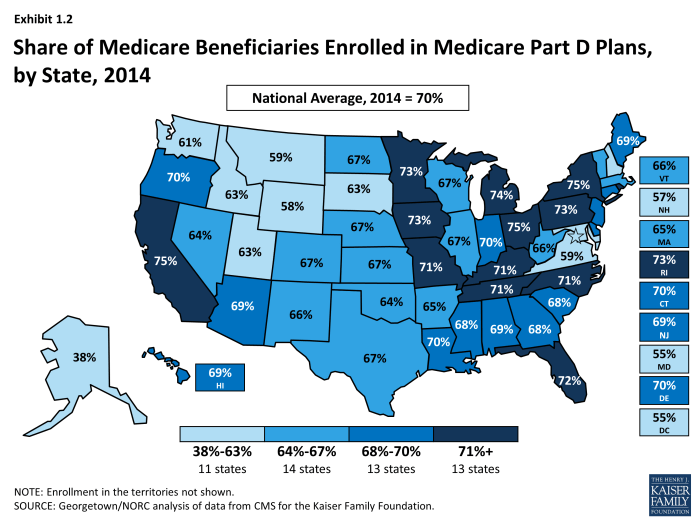

The share of Medicare beneficiaries with Part D coverage varies considerably by state (Exhibit 1.2). States with the highest shares of Part D enrollment are California, New York, and Ohio, each with 75 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in Part D. Six states and the District of Columbia have fewer than 60 percent of their residents on Medicare in Part D plans. These states include several with high shares of federal employment; federal retirees get drug coverage outside Part D through the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. The lowest level is 38 percent in Alaska.

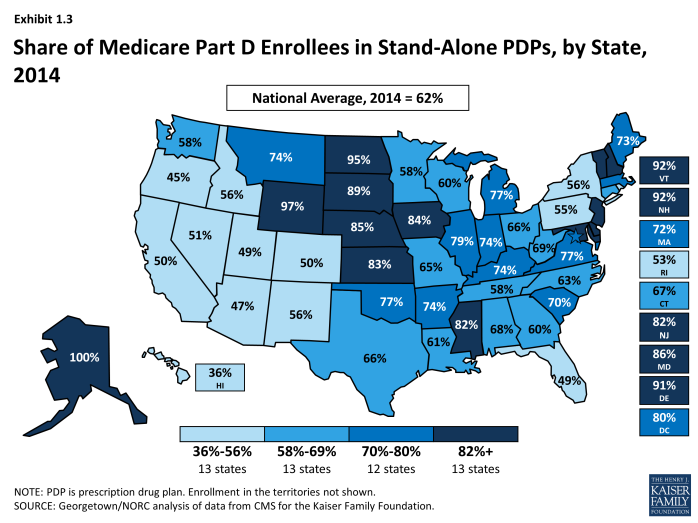

Nationally, about 62 percent of Part D enrollees are in PDPs; the remaining 38 percent are in MA-PDs, with considerable variation by state (Exhibit 1.3), Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2. PDP enrollment accounted for 72 percent of total enrollment in 2006, but this share has been declining over time as MA-PD plan enrollment has grown more rapidly than PDP enrollment in recent years. From 2006 to 2014, non-employer MA-PD plan enrollment grew by 10.5 percent annually, whereas non-employer PDP enrollment grew by only 2.3 percent annually. PDPs account for 100 percent of Part D enrollees in Alaska and more than 90 percent of enrollees in five other states with low populations (Delaware, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming). By contrast, MA-PD plans account for half or more of Part D enrollees in seven states. The highest shares of Part D enrollees in Medicare Advantage drug plans are in California, Florida, and several western states.

Between 2011 and 2014, total enrollment in employer-only Part D plans more than doubled from 2.9 million to 6.5 million beneficiaries (Exhibit 1.4), Appendix Table 2. Total enrollment in employer-only Part D plans in 2014 is more than four times the level in 2006, the program’s first year. The biggest increase was between 2012 and 2013, when enrollment in these plans grew 63 percent. The growth rate slowed in 2014, but enrollment in employer-only plans still grew 10 percent.

The major impetus for this growth was a provision in the ACA that eliminated the tax deductibility of the 28 percent Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS), effective in 2013.3 This subsidy, paid to employers who provide creditable prescription drug coverage to Medicare beneficiaries, was included in the original Part D legislation to encourage employers to maintain existing drug coverage for their retirees. In 2006, 7.2 million Medicare beneficiaries were covered in retiree health plans that received the RDS (with an average subsidy payment of $527 per person in 2006, rising to a projected $605 in 2014). With the changed tax status of the RDS, enrollment in subsidized retiree plans dropped to 3.3 million in 2012, and the Medicare Trustees project a drop to 0.9 million by 2019.4

Most employers that no longer elected to receive the subsidy after the change in tax treatment have shifted their retirees to employer-only Part D plans. Most of the new enrollment was in employer-only PDPs. In 2013, enrollment was up 99 percent in employer-only PDPs and just 7 percent in employer-only MA-PD plans. In 2014, growth slowed overall, and there was a somewhat greater increase in employer MA-PD plan enrollment.

Continuity of Part D Plan Offerings

About one out of four PDPs that participated in Part D in its first year are still in the market today. There are 398 PDPs operating under the same contract and plan identification number in 2014 as in 2006. About one-fourth of these PDPs operate under the same plan name, while others have similar names. For example, what was originally the AARP MedicareRx Plan, sponsored by UnitedHealth, is now called AARP MedicareRx Preferred. Others have changed as a result of acquisitions; for example, the PDP offered as PacifiCare Comprehensive Plan in 2006 is now UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Enhanced PDP. About one-third of these continuously operating PDPs have changed their benefit type; in most cases, PDPs originally offering the basic benefit now offer an enhanced benefit.

These continuously operating PDPs accounted for nearly half of all PDP enrollees in 2006, and 57 percent in 2014. Most of the remaining PDP enrollees are in other plans offered by sponsors that have participated in Part D since 2006. Of the six plan sponsors that entered the Part D after the program’s first year, none have attracted a significant market share. The most successful new entrant has been Envision RxPlus, which held a 2.5 percent share of PDP enrollment in 2013, declining to 2 percent in 2014.

Part D Market Concentration

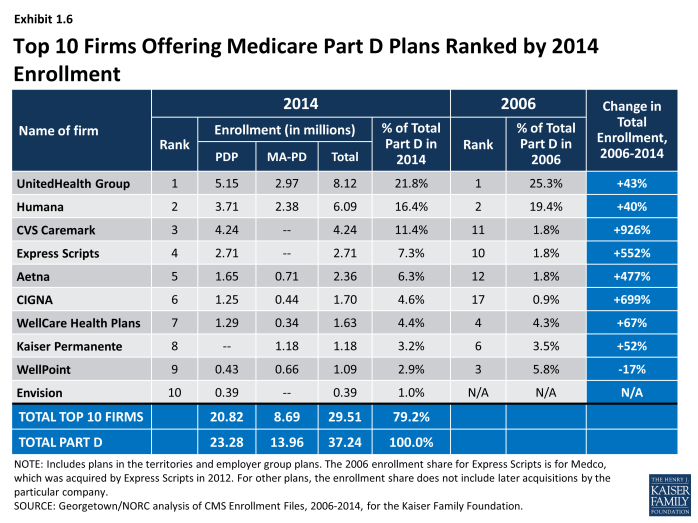

In 2014, the ten largest sponsors of Part D plans account for more than three-fourths of all enrollees, three firms account for half of all enrollees, and UnitedHealth alone accounts for more than one in five Part D enrollees (including 22 percent of PDP enrollees and 21 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees) (Exhibit 1.5).5 This pattern of a few plan sponsors having a substantial share of Part D enrollment has held over the program’s first nine years. The ten largest Part D plan sponsors in 2014 have enrolled 29.5 million beneficiaries in either a stand-alone PDP or an MA-PD plan (Exhibit 1.6).6 The share of enrollment in the ten largest plans in 2014 (79 percent) is higher than in 2006 (69 percent). In 2006, the top three firms also accounted for about half of all enrollees.

Six of the top ten firms in 2014 sponsor both stand-alone PDPs and MA-PD plans. Kaiser Permanente is the only sponsor among the top ten that offers only MA-PD plans, and Wellpoint is the only other firm with more MA-PD enrollees than PDP enrollees. CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and Envision offer only PDPs. Other than Kaiser Permanente, at least 40 percent of each of the top firms’ enrollment is in PDPs.

Enrollment growth since 2006 for CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, Aetna, and CIGNA is due largely to acquisitions of other plan sponsors. CVS Caremark has used an acquisitions strategy to become the third largest sponsor in the Part D marketplace—despite being suspended for new enrollment in its PDP products in the annual enrollment period for 2014. The parent company now includes 5 of the 18 firms that had the most enrollees in 2006.7 CIGNA and Aetna have grown their Part D market shares through similar acquisitions strategies. Express Scripts has grown both through its recent acquisition of Medco, but also through the overall increase in enrollment in employer-only plans since the RDS tax status change. Four plan sponsors dominate the employer-only segment of the Part D market, collectively accounting for about two-thirds of all enrollees in employer-only Part D plans: Express Scripts (34 percent), CVS Caremark (18 percent), UnitedHealth (8 percent), and Kaiser Permanente (7 percent).

UnitedHealth and Humana have been the two largest Part D plan sponsors from the start of the program, but their combined share of enrollment has dropped from 45 percent in 2006 to 38 percent in 2014. UnitedHealth, due in part to its successful marketing relationship with AARP, has maintained its top position for all nine years of the program and has seen its enrollment grow by about 43 percent since 2006. Humana has maintained a strong Part D presence, due in part to offering the lowest PDP premiums in 2006 and retaining many of those enrollees over time despite premium increases for its older plans. While higher-than-average premium increases and a loss of LIS benchmark status in most regions contributed to a drop in Humana’s Part D enrollment between 2006 and 2010, Humana’s introduction of new PDPs in 2011 and 2014 reversed this decline, contributing to a net enrollment gain of 40 percent in Humana’s Part D plans between 2006 and 2014.

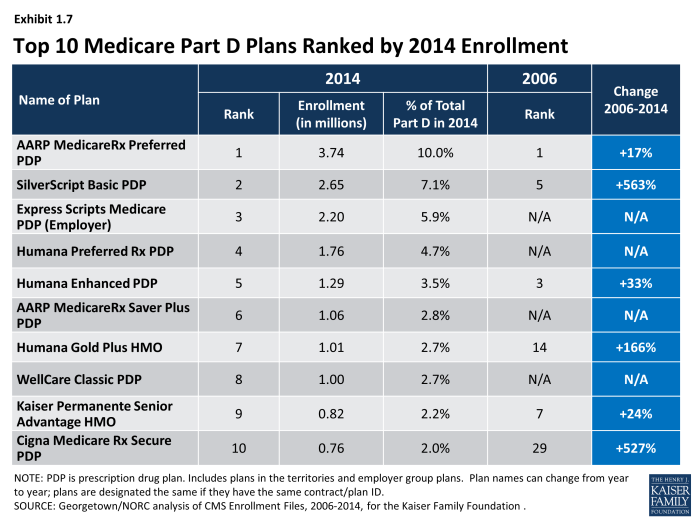

There has been more turnover in the list of top Part D plans than plan sponsors, with only four of the top ten PDPs or MA-PD plans by enrollment in 2014 among the top ten in 2006. These four plans are UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP, Humana’s Enhanced PDP, CVS Caremark’s SilverScript Basic PDP, and Kaiser Permanente’s Senior Advantage HMO (Exhibit 1.7). Within many plan sponsors’ offerings, there have been significant changes in enrollment, partly due to sponsors adding, dropping, or consolidating plans. Two of the top plans in 2014 (Humana’s Preferred Rx PDP and UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP) are recent entries to the market, featuring low initial premiums and preferred pharmacy networks.

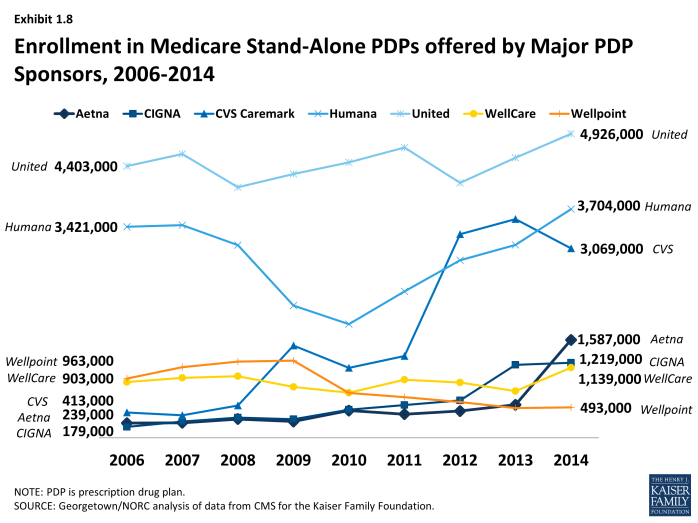

The growth pattern among the largest PDP sponsors illustrates some of the different strategies used since the start of the program (Exhibit 1.8). UnitedHealth has been the largest PDP sponsor since 2006, and Humana has generally been the second largest. CVS Caremark has used an acquisition strategy to move solidly into the third position. Aetna and CIGNA have moved higher up in recent years, also through acquisitions.

Enrollment shifts among the top plans and plan sponsors also have been brought about by automatic re-assignment of LIS beneficiaries. If a plan loses its designation as a benchmark plan (available to LIS beneficiaries for zero premium), CMS reassigns certain beneficiaries to a benchmark plan offered by the same sponsor if one is available; otherwise they are switched at random to a benchmark plan offered by another sponsor.

The most popular plans vary considerably by region. UnitedHealth has the largest PDP in a majority of regions in 2014.8 The firm’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP is the largest PDP in 25 regions, and the SilverScript Basic PDP is the largest in 7 regions. Humana Preferred Rx PDP holds the lead in Colorado, and MedicareBlue Rx Standard PDP has the largest share of enrollment in the seven-state upper Midwest region.

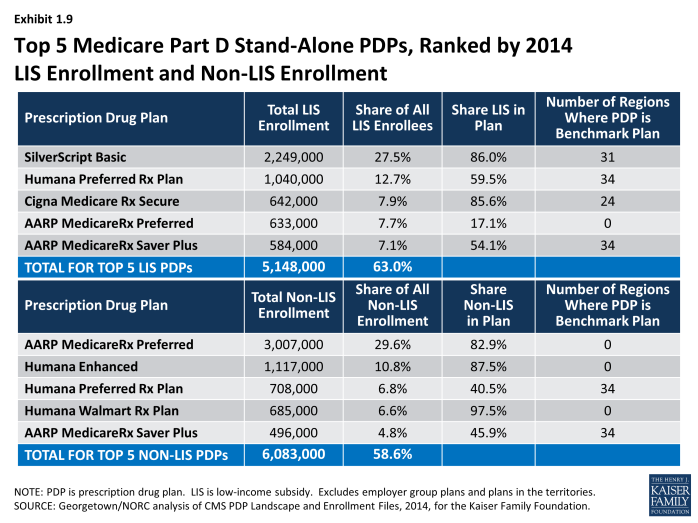

The most popular plans also differ for non-LIS and LIS beneficiaries. In addition to being the largest plan overall, AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP has enrolled about 30 percent of all non-LIS enrollees nationally and has the most non-LIS enrollees in 31 of 34 PDP regions (Exhibit 1.9). Local Blue Cross Blue Shield PDPs have the largest share of non-LIS enrollment in Arkansas and the upper Midwest region, and Humana’s Enhanced PDP has the most non-LIS enrollees in the Idaho/Utah region.

With the help of its acquisition strategy, CVS Caremark’s SilverScript Basic PDP dominates the LIS market with more than one-fourth of national LIS enrollment and the highest share of LIS enrollees in 26 PDP regions, despite not receiving any new enrollees during the annual enrollment period. PDPs sponsored by Humana, UnitedHealth, Aetna, and CIGNA have the most LIS enrollees in the other 8 PDP regions. Like many PDPs with high LIS enrollment, SilverScript Basic PDP has attracted only a small share (14 percent) of non-LIS enrollees. By contrast, Humana’s Preferred Rx PDP and UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDPs have attracted enrollment in nearly equal shares from both non-LIS and LIS beneficiaries, and they are among the top five plans by enrollment in each category. UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP has more than 600,000 LIS enrollees, despite its status as an enhanced PDP that charges a premium for LIS enrollees and despite the availability of a UnitedHealth PDP with a much lower premium that would be available to LIS beneficiaries for zero premium because it qualifies as a benchmark plan in all 34 regions.

Concentration of enrollment among PDPs nationally (at the plan level), as measured by a statistical measure of market competition, has declined since 2011 as enrollment has grown in the some of the newly offered PDPs. Concentration is greater within regions than at the national level.9 Furthermore, if non-LIS and LIS beneficiaries are treated as separate markets, both are more concentrated—especially within regions.10 The most concentrated regions tend to be in the northeastern and southwestern states.

Plan Availability

Choice remains plentiful in Part D; in 2014, the average Part D enrollee had a choice of 35 PDPs and 15 MA-PD plans. The average number of PDPs per region has come down from a high of 56 in 2007 to 35 in 2014 (weighted by regional enrollment). At least 28 PDPs are offered in every region this year (excluding the territories). In 2014, virtually all beneficiaries have at least one Medicare Advantage option with drug coverage as well, and the average beneficiary has 15 options for Medicare Advantage drug plan enrollment.11

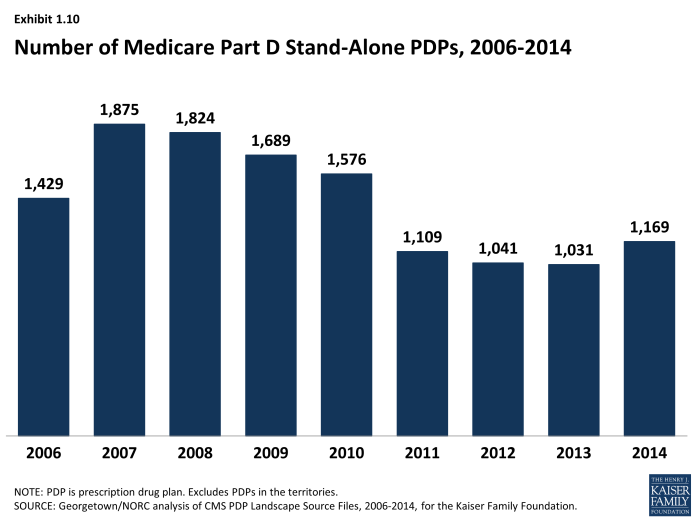

The number of PDPs offered increased somewhat between 2013 and 2014. There are 1,169 PDPs in 2014, up 13 percent compared to 2013, but still well below the number of PDPs offered between 2006 and 2010. While the number of PDPs rose sharply between 2006 and 2007, the number decreased each year until 2014 as a result of both marketplace and policy factors (Exhibit 1.10). Over its first nine years, the Part D market has witnessed several mergers between sponsoring organizations and consolidation of plan offerings by sponsors. In 2010, CMS issued regulations aimed at discouraging duplicative plan offerings and plans with low enrollment. For example, many sponsors now offer just two plan options (one basic and one enhanced) instead of the three options they had offered in previous years.

The modest increase in PDP offerings from 2013 to 2014 reflects new offerings by both existing plan sponsors and sponsors new to the program in 2014 as well as a few offsetting plan terminations. Symphonix Health is offering a new basic PDP in 30 regions, co-branded in some regions with Rite Aid pharmacies. Stonebridge Life Insurance Company offers new basic and enhanced PDPs in 33 regions under the Transamerica MedicareRx name. Together with two smaller plan sponsors, new plan sponsors offered 102 PDPs, but they attracted fewer than 700 enrollees per plan on average. Because some of these plans had premiums below the LIS benchmark amount in some regions, they received some enrollees through random assignments or reassignments by CMS (described in more detail in the section below on the Low-Income Subsidy Program). Existing plan sponsors added another 110 new PDPs to the market (some replacing existing PDPs and others replacing PDPs they had dropped a year earlier). One—Humana’s Walmart Rx PDP—attracted 660,000 enrollees (20,000 per region), but the others attracted only an average of 1,250 enrollees each. In addition, Envision RxPlus dropped the enhanced PDP it first offered in 2007, which did not attract a large number of enrollees.

Current CMS policies suggest that the number of PDPs might decline again in future years. In the call letter issued in early 2014 spelling out the terms of plan participation for the 2015 contract year, CMS reiterated the agency’s authority not to renew plans with low enrollment.12 Currently, 330 PDPs (28 percent of all PDPs in 2014) have fewer than 1,000 enrollees, the level at which CMS urges sponsors to consider plan withdrawal or consolidation; 105 of these PDPs have fewer than 100 enrollees each.13 The low-enrollment PDPs include many plans offered for the first time in 2014.

In addition to its policy on low-enrollment plans, CMS continues to maintain a policy that PDPs offered by the same sponsor must be meaningfully different from the sponsor’s other offerings. This policy encourages plan sponsors to reduce their PDP offerings, thereby simplifying the choice environment in Part D. In a rulemaking notice published in May 2014, the agency noted its intention to continue monitoring its policy on meaningful differences to determine whether changes may be necessary as the coverage gap closes.14

In 2014, 1,610 Medicare Advantage drug plans are offered, essentially the same number as the year before. The number of MA-PD plans increased by about 50 percent between 2006 and 2009, from 1,333 plans to 1,991 plans.15 However, the availability of MA-PD plans has fallen since then; the 1,610 MA-PD plans offered in 2014 is about 19 percent lower than at the peak.

Section 1: Part D Enrollment and Plan Availability

exhibits

Section 2: Part D Premiums

National Premium Trends

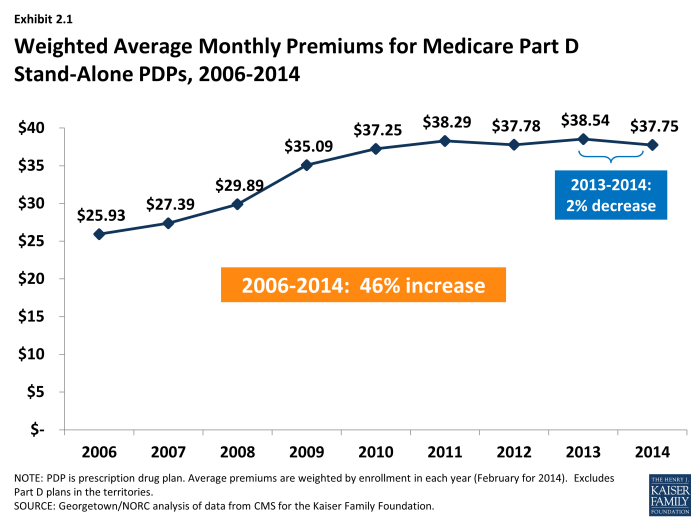

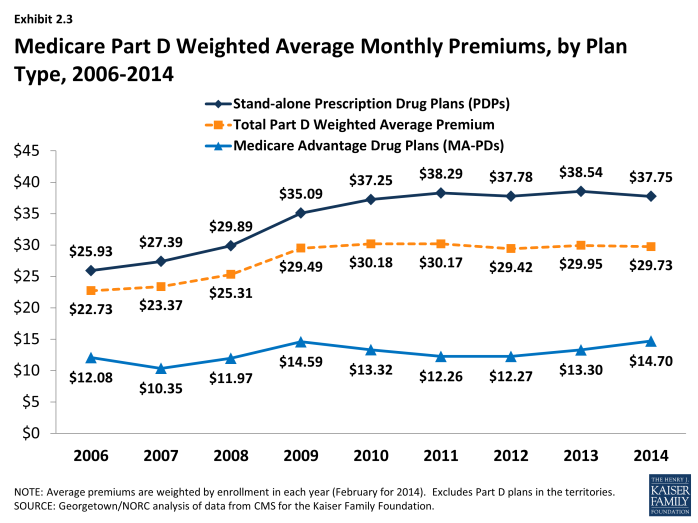

Since 2006, the average PDP premium, weighted by enrollment, has increased by 46 percent, but the 2014 average is 2 percent lower than in 2013. The weighted average monthly premium paid by beneficiaries for stand-alone Part D coverage has increased since the start of the program, from $25.93 in 2006 to $37.75 in 2014 (Exhibit 2.1).1,2 Premiums have been essentially flat since 2010, up only 1 percent from 2010 to 2014. A key factor driving slow premium growth in recent years is the availability of generic versions of many drugs used for common chronic conditions, which helps to limit growth in total plan costs and hence premiums.3 National per capita expenditures on prescription drugs have grown considerably more slowly than Part D premiums from 2006 to 2014, up just 15 percent.4

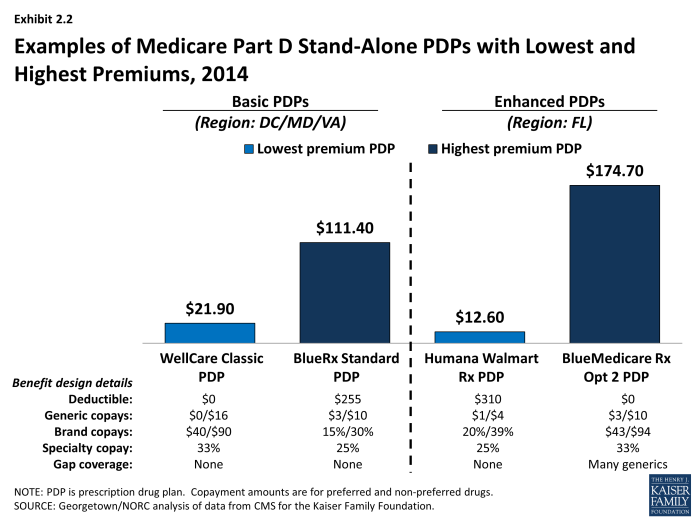

PDP premiums vary widely. Nationwide, the least expensive PDP has a $12.50 monthly premium, while the most expensive PDP has a $174.70 premium, a 14-fold difference. Although the difference can be explained partly by the relative generosity of the benefits offered or the relative efficiency across plans, these factors seem unlikely to explain the full difference. Even among plans with equivalent benefits (those offering the basic Part D benefit), premiums vary from $12.80 to $111.40 per month. As illustrated in the lowest and highest-premium PDPs in selected regions, benefit differences are modest relative to the large premium differences (Exhibit 2.2). Although enrollees in the highest-premium enhanced plan have some coverage in the gap for generic drugs and no deductible, they face cost sharing similar to that in the lowest-premium PDPs. Those enrolled in the highest-premium basic PDP have a $255 deductible while those in the lowest-premium PDP have no deductible.

Average Part D premiums, including both PDPs and MA-PDs, are lower than average premiums for PDPs because MA-PD plan premiums are less than half of those for PDPs. The combined average has been essentially flat since 2010, hovering around $30 (Exhibit 2.3). The average 2014 monthly premium amount attributable to drug benefits in MA-PD plans is $14.70, up 11 percent from $13.30 in 2013, and higher than in any year since the program began.5 The MA-PD average monthly premium is about $23 below the PDP average monthly premium, in part because many MA-PD plans reduce or eliminate their premiums by using a portion of rebates from the Medicare Advantage payment system.6 The modest increase in the MA-PD premium from 2013 to 2014 may reflect changes in the Medicare Advantage payment rules, which may have lowered these rebates. Nearly half (46 percent) of all MA-PD plans charge no premium for their drug benefit.

Plan-Level Premium Trends

Four of the seven PDPs with the highest enrollment charged higher average premiums in 2014 compared to 2013, whereas three lowered their average premiums. More generally, the modest decrease in the average premium for all Part D enrollees hides larger changes at the plan level (Exhibit 2.4). The plan with the highest enrollment, UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP, increased the monthly premium by 7 percent compared to 2013 (from $40.45 to $43.41). By contrast, UnitedHealth’s Saver Plus PDP increased its average premium by 54 percent (from $15.00 to $23.11). WellCare’s Classic PDP had the largest decrease among PDPs with the most enrollment, lowering its premium from $33.39 to $20.66, a 38 percent decrease.

Older, established plans generally have raised premiums more rapidly than the national average, while newer plans are more likely to set premiums low in order to build enrollment. As a result, beneficiaries who stay in the same plan tend to pay more over time, as earlier research finds relatively few enrollees switch plans voluntarily in a given year.7 Established plans tend to retain enrollees as they age, when they typically use more drugs, whereas newer plans attract younger enrollees who are likely to have lower drug use and also more likely to shop based on premiums when they first enter the market. Premiums for some new plans have increased rapidly within a year or two of entering the market. For some plan sponsors, this strategy may be a conscious attempt to attract younger enrollees in newer, less expensive plans while still retaining their existing enrollees in older, more expensive plans.

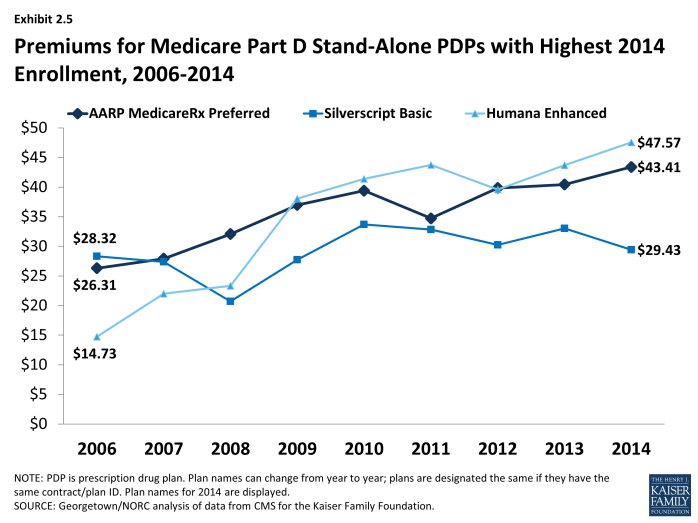

Most plans that have been in the program since 2006 have increased premiums by more than the national average. Overall, of 398 PDPs that have operated under the same contract and plan numbers from 2006 to 2014 (despite some corporate acquisitions and name changes), about half have monthly premiums in 2014 that are at least double the premium in 2006, and three-fourths have raised premiums over this period by more than the national average increase. For example, the average monthly premium for Humana’s Enhanced PDP in 2014 is more than three times its 2006 average ($47.57 versus $14.73) (Exhibit 2.5). By contrast, one in six of these continuously operating PDPs has a lower premium in 2014 than in 2006. Silverscript Value PDP had nearly the same premium in 2006 and 2014 ($28.32 versus $29.43) (although there was some premium variation in the intervening years).

Enrollment in UnitedHealth’s AARP Medicare Saver Plus PDP was up by 46 percent between 2013 and 2014 even with an increase of $8 (54 percent) in the premium. Some of the enrollment gain came from random assignment of LIS enrollees, but enrollment by non-LIS beneficiaries was up by 20 percent as well. Of the three large PDPs with premium decreases from 2013 to 2014, two added enrollees.8 Our analysis of plan switching from 2006 to 2010 found that 87 percent of beneficiaries in any particular annual enrollment period did not change plans.9 Those whose premiums were increasing by $10 or more were more likely to change to plans with lower premiums; 21 percent of those with a $10 to $20 premium increase and 28 percent of those with a premium increase of $20 or more made a change of plans.

As with PDPs, average premiums vary considerably by MA-PD plan sponsor. Plans offered by UnitedHealth, with 20 percent of the MA-PD market, have a weighted average premium of $2.94 for the drug benefit (in addition to a Part C premium of $3.93 that covers the medical benefits normally provided by traditional Medicare). By contrast, Humana, the second largest company in this market segment (19 percent of MA-PD enrollees) has an average premium of $15.05 (plus $18.27 for Part C). The next two largest MA-PD sponsors are Kaiser Permanente, with a 6 percent market share and a $4.46 average premium (plus $39.27 for Part C), and Aetna, with a 4 percent market share and a $9.26 average premium (plus $10.39 for Part C).10

Geographic Variations in Premiums

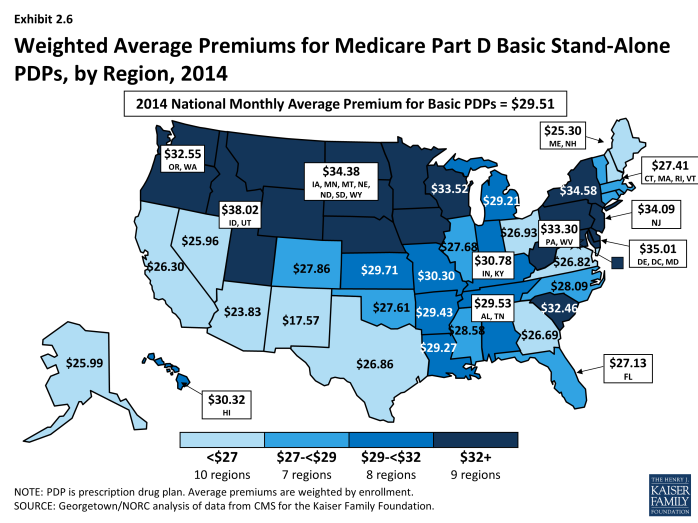

Average premiums are considerably higher in certain regions than in others in 2014. Beneficiaries enrolled in a basic PDP in New Mexico in 2014 pay an average of $17.57 per month; those in the Idaho/Utah PDP region pay $38.02, more than double the average in New Mexico (Exhibit 2.6).11 Regional differences in premiums have generally persisted from year to year and continued to grow wider in 2014. New Mexico and Arizona have been among the regions with the lowest average premiums since the program began, while the Idaho/Utah region has been among the most expensive regions.

At the same time, some regions have seen significant changes in their average PDP premiums relative to other regions. The average PDP premium in New York, for example, was below the national average from 2006 to 2010, and then increased to be above average each year since then. Regional differences in the average PDP premium were smaller in the program’s first two years, before plan sponsors could look at actual claims experience for guidance in setting premium levels. Although persistent regional differences in premiums are driven in part by underlying regional differences in drug utilization, further explanations are not readily apparent.

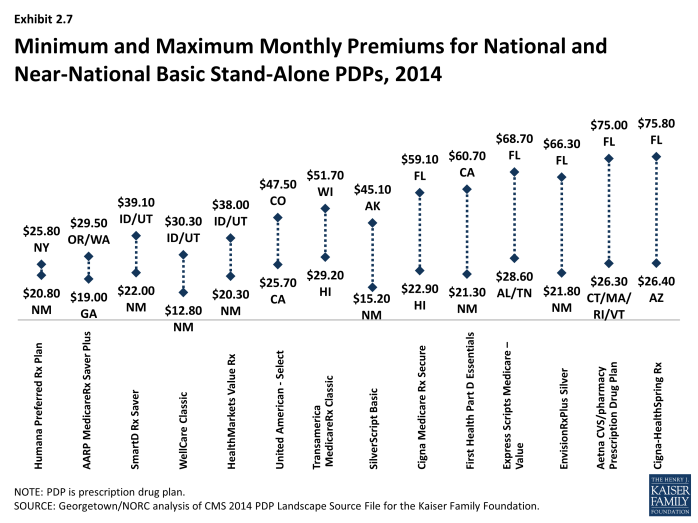

Geographic differences in premiums are greater for some plan sponsors than others; some sponsors charge as much as two or three times more for the identical basic PDP from one region to another. Fourteen plan sponsors offer a basic PDP in at least 29 of the 34 PDP regions. For eight of these national or near-national PDPs, premiums for the identical plan design are more than two times greater in one region than in another (Exhibit 2.7). The largest absolute premium difference is for the Cigna-HealthSpring PDP, which charges beneficiaries $26.40 in Arizona and $75.80 in Florida for the same coverage. By contrast, the Humana Preferred Rx PDP has a difference of only $5.00 between its lowest and highest regions ($20.80 in New Mexico and $25.80 in New York). For five of these national or near-national PDPs, the highest premium is in Florida, even though Florida premiums overall are below the national average.

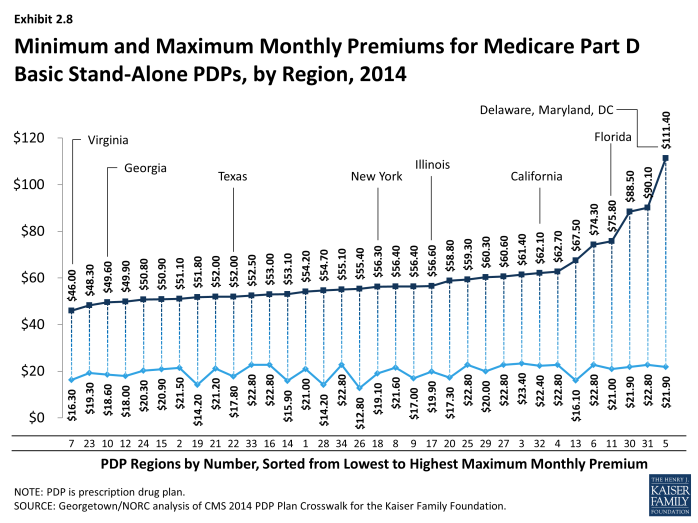

Within each region, some plan sponsors charge several times more than competing sponsors for their basic PDPs (Exhibit 2.8). In Virginia, the highest premium for a basic PDP is $46.00 for the new Transamerica MedicareRx Classic PDP, which is nearly three times the $16.30 premium for the WellCare Classic PDP. The highest premium for a basic PDP is even higher in the region that includes Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, DC, where the BlueRx Standard plan charges $111.40, five times the lowest premium in its region ($21.90 for WellCare Classic PDP). By law, all basic PDPs provide a benefit with the same actuarial value. Different utilization patterns by plan enrollees (adverse selection, beyond what can be compensated for by the risk-adjustment system used by CMS) may be a key factor driving the larger premium differences.

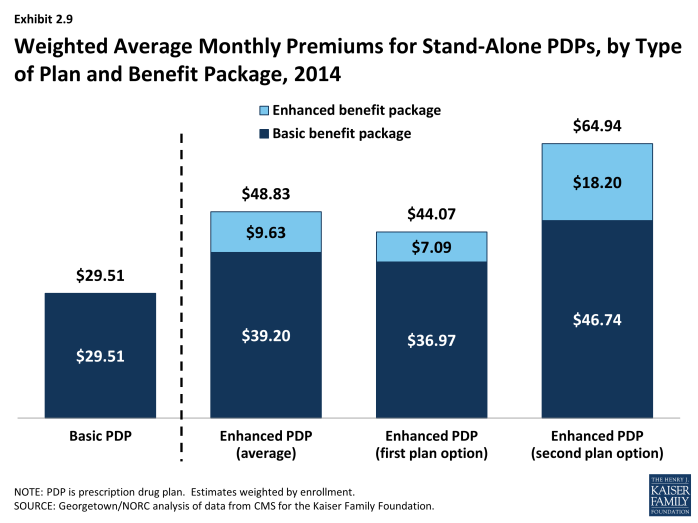

Premium Variations by Plan Type

Beneficiaries selecting PDPs with an enhanced benefit package pay higher premiums on average for their Part D coverage, even for the part attributable to the basic benefit package. The weighted average monthly premium for PDPs with enhanced benefits is $48.83, compared to $29.51 for PDPs offering the basic benefit package (Exhibit 2.9). Thus, enrollees pay about 65 percent more to get enhanced benefits.

Plan sponsors mostly add value in their enhanced plans by lowering deductibles and sometimes adding coverage in the gap. Most enhanced plans lower or eliminate plan deductibles; 89 percent of enhanced PDPs have no deductible, compared to 6 percent of basic PDPs. If eliminating the deductible were the only difference, beneficiaries would be paying an additional premium of $19.32 per month ($48.83 versus $29.51) or $232 annually to eliminate a $310 deductible. Some enhanced plans also expand the coverage of drugs during the coverage gap beyond the amount included in the basic benefit (36 percent of enhanced PDPs). Plans may also use lower cost sharing as part of an enhanced benefit, but this is a less common feature of enhanced PDPs in 2014. Analysis of enhanced PDPs in earlier years sometimes revealed only small benefit differences compared to the same sponsor’s basic PDPs.12

Starting with PDPs offered in 2011, CMS has required sponsors to ensure that benefits in enhanced PDPs are meaningfully different than the basic benefits and have a measurable added value. This policy has led to a larger spread between premiums for enhanced PDPs and basic PDPs than in previous years. In 2014, an enhanced PDP must have cost-sharing differences that result in at least $21 lower monthly out-of-pocket costs than the corresponding basic PDP—an amount that modestly exceeds the $14.56 premium difference between basic plans and less extensive enhanced PDPs ($29.51 versus $44.07).

Some PDP sponsors offer two enhanced plans, a less generous first option and a more generous second option; average monthly premiums for the more generous enhanced PDPs are higher than the premium of the first option ($64.94 versus $44.07). As part of its policy on meaningful differences, CMS allows sponsors to offer a second enhanced PDP only if expected out-of-pocket cost sharing amounts are lower (by $18 per month) than for the first enhanced PDP and the second enhanced PDP has coverage for at least some brand drugs in the coverage gap. The $20 difference in premiums slightly exceeds the required difference in out-of-pocket costs.13

Although higher premiums partly reflect the cost of offering enhanced benefits, the portion of the premium that corresponds to the basic benefit ($39.20 on average for enhanced PDPs) is higher than the premium for basic PDPs ($29.51) (Exhibit 2.9). For some sponsors, the difference is much greater. Risk selection may be a factor in these higher premiums to the extent that the enhanced plans have attracted beneficiaries with higher drug needs beyond differences captured by risk adjustment.

Some plan sponsors offer enhanced PDPs that have the minimum level of enhanced coverage required by the meaningful difference tests and are offered at low premiums with the apparent goal of attracting beneficiaries with low expected drug costs.14 In 2014, monthly premiums for two of these enhanced plans are less than those for the same sponsors’ basic plans. Humana’s new enhanced PDP is offered at $12.60 per month, whereas its basic PDP (Preferred Rx) is $22.74. Similarly, the enhanced PDP offered by Aetna/First Health is $44.53 per month, compared to $51.09 for the comparable basic PDP. For several other plan sponsors, the portion of the premium attributable to a plan’s basic benefits (thus excluding the value of any enhanced benefit) is lower for their enhanced PDPs compared to their basic PDPs.

A key reason for lower premiums in these enhanced plans is favorable risk selection that occurs because they are attractive to non-LIS beneficiaries who are using few drugs and because there are few LIS beneficiaries enrolled in enhanced plans. CMS does not automatically enroll LIS beneficiaries in enhanced plans. LIS beneficiaries may choose an enhanced plan but must pay the full premium amount attached to the enhanced portion of the benefit, even if the total premium is below the LIS benchmark (which is the case for 43 PDPs in 2014). In 2014, LIS enrollees represent 68 percent of all enrollees in basic PDPs, but only 11 percent of those in enhanced PDPs. In its May 2014 rulemaking, CMS noted its intention to continue monitoring the incentives for favorable risk selection and assessing the need for policy measures to address any market segmentation.15

Section 2: Part D Premiums

exhibits

Section 3: Part D Benefit Design and Cost Sharing

Plan Benefit Design

Most Part D plans do not offer the defined standard benefit (with a $310 deductible in 2014 and 25 percent coinsurance); the vast majority have a tiered cost-sharing structure with incentives for enrollees to use less expensive generic and preferred brand-name drugs. In 2014, only 3 percent of PDPs and 2 percent of MA-PD plans offer the defined standard benefit that has no formulary tiers (with 2 percent and 1 percent of enrollment, respectively).

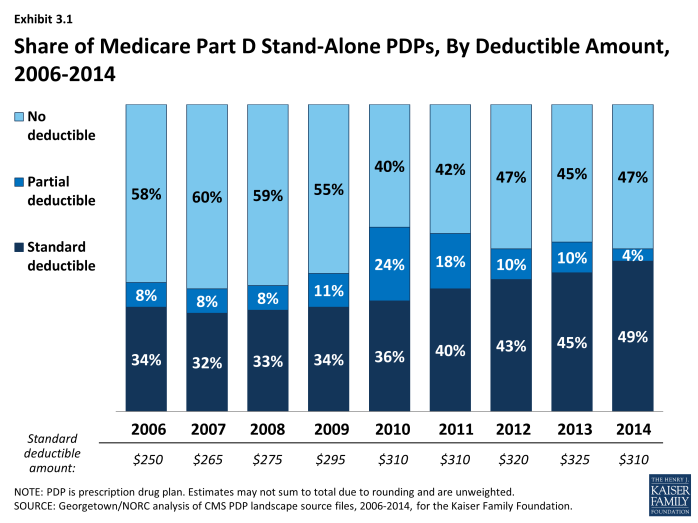

Use of a deductible by stand-alone PDPs is considerably higher in 2014 than in the first few years of the program, but down somewhat since 2010 (Exhibit 3.1). About 53 percent of PDPs charge a deductible this year, compared to a high of 60 percent in 2010. Most PDPs with a deductible use the standard deductible allowed by law ($310 in 2014). A far smaller number of MA-PD plans (14 percent) than PDPs have a deductible in 2014.

In 2014, about three-fourths of all plans (76 percent of PDPs and 75 percent of MA-PD plans) use five cost-sharing tiers: preferred and non-preferred tiers for generic drugs, preferred and non-preferred tiers for brand drugs, and a tier for specialty drugs. About 73 percent of PDP enrollees and 81 percent of MA-PD enrollees are in plans with five tiers. Most of the other Part D enrollees are in plans with four tiers: one generic tier, two brand tiers, and a specialty tier.1 Four-tier arrangements were most common until 2012 when plans began shifting toward the five-tier cost-sharing design.

Part D Cost-Sharing Amounts

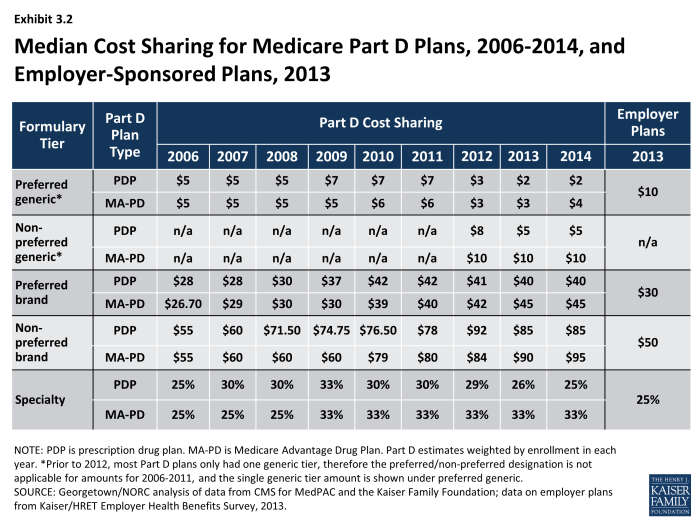

While cost sharing has been relatively stable in recent years, the median cost sharing for a 30-day supply of “non-preferred” brand-name drugs in stand-alone PDPs has increased by 55 percent since 2006, from $55 to $85, while cost sharing for preferred brand drugs increased by 43 percent, from $28 to $40 (Exhibit 3.2). From 2011 to 2014, the spread between tiers widened modestly. Median cost sharing for preferred generic drugs in PDPs (or for generic drugs among plans with a single generic tier) is $2 in 2014, lower than in any year since the program began. For PDPs with two generic tiers (about two-thirds of all PDPs and PDP enrollment), the median cost sharing is $2 for the preferred generic tier and $5 for the non-preferred tier (the same as in 2013). Some PDPs set cost sharing for their non-preferred generic tier as high as $33.

Cost-sharing amounts for brand-name drugs vary widely across Part D plans in 2014, as they have in previous years. For preferred brand tiers, PDPs set copayment levels as low as $17 and as high as $45; for non-preferred tiers, the copayments range from $35 to $95. These ranges are less than in some previous years because of CMS guidance that sets maximum allowable copayment levels.

In 2014, median cost-sharing amounts are generally higher in MA-PD plans than in PDPs in all tiers.2 For example, the median cost sharing for preferred brands in MA-PD plans is $5 more than the median in PDPs ($45 versus $40) and $2 more for preferred generic drugs ($4 versus $2) (Exhibit 3.3). The comparisons for UnitedHealth, the sponsor with largest share of both PDP and MA-PD enrollment, illustrate the pattern. For preferred and non-preferred generic drugs, UnitedHealth’s median cost sharing, weighted by enrollment, is $3 and $6 in its PDPs and $4 and $8 in its MA-PD plans, respectively. The differences for brand drugs for UnitedHealth’s plans mirror the national differences. Higher cost sharing for MA-PD plans is surprising, given the incentives for MA-PD plans to encourage use of drugs that might reduce other types of health care costs. Further work is needed to assess variations in copayments by Part D plan type, including for example, the extent to which these differences persist across all plan sponsors and within different geographic areas, as well as whether differences in tier placement of specific drugs or whether some plans cover more drugs than others on specific tiers may be a factor in explaining differences in cost-sharing amounts between types of Part D plans.

Copayments in the form of a flat dollar payment amount remain the most common type of cost sharing; however, the share of PDPs using percentage-based coinsurance for non-specialty brand-name drug tiers has increased since 2006. In 2014, 37 percent of PDPs with a tier for non-preferred brand drugs charge a coinsurance rate for drugs on that tier. Of these plans, nearly all have a mixed pricing design. Typically they use a flat copayment for their generic drug tiers, and many also use a flat copayment for preferred brand drugs. The use of percentage coinsurance for drugs remains uncommon among MA-PD plans.

For plans that use percentage coinsurance instead of dollar copayments, the actual amount an enrollee pays depends on the retail price of the drug. The median coinsurance percentage for PDPs in 2014 for the preferred brand tier is 20 percent. For drugs on the non-preferred brand tier, the median coinsurance rate is 40 percent, a substantial share of the drug’s cost. In fact, 39 PDPs require beneficiaries to pay half the cost of drugs on the non-preferred brand tier (which is less than the 75 percent coinsurance applied in some previous years).

Medicare Part D plans generally charge more than private-sector employer plans do for preferred and non-preferred brand drugs, but less for generics. At the median, PDPs charge $40 per month for a preferred brand in 2014, higher than the median $30 charged by employer plans in 2013, the most recent available data (Exhibit 3.2).3 Cost-sharing differences are even greater for non-preferred brands ($85 for PDPs versus $50 for employer plans). By contrast, employers charge much higher copays for generic drugs than PDPs charge ($10 versus $2). Thus the spreads between cost sharing for brands and generics and between preferred and non-preferred brand drugs are greater in Medicare Part D plans. Compared to commercial health plans, the typical structure of cost sharing in Part D offers a greater incentive for plan enrollees to choose generics or preferred brand drugs.

Specialty Tiers

Specialty drugs appear to be one of the faster-growing segments of the Part D drug benefit. According to one of the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), the growth trend for specialty drugs in Medicare in 2013 was 14.7 percent, compared to no growth for non-specialty drugs.4 The growth for specialty drugs was entirely driven by increases in unit cost, rather than utilization. Although the drugs are expensive, specialty drugs represented only 11 percent of Part D drug spending in 2013.5

Most Part D plans use a specialty tier for high-cost medications in 2014. In 2014, among Part D enrollees in plans using tiered cost sharing, 96 percent of PDP enrollees and 98 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with a specialty tier. Specialty tiers are commonly used by Medicare drug plans for relatively expensive drugs (at least $600 per month in 2014—a level that has been unchanged since 2008).

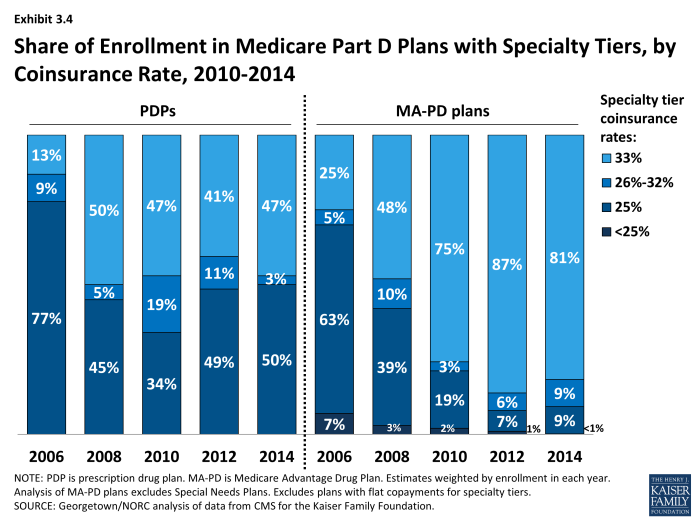

About half of PDP enrollees and most MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with a 33 percent coinsurance rate for specialty tier drugs. While CMS limits the coinsurance rate for drugs placed on a specialty tier to 25 percent, plans are allowed to impose higher cost sharing (up to 33 percent) for specialty tier drugs if offset by a lower deductible.6 In 2014, about 47 percent of PDP enrollees are in plans charging 33 percent coinsurance for specialty drugs in the initial coverage period (Exhibit 3.4). By contrast, in 2006 only 13 percent of beneficiaries in PDPs with specialty tiers faced a 33 percent coinsurance rate for the specialty tier. In 2014, 81 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with 33 percent coinsurance for specialty drugs—well above the 48 percent share in 2008.

Most plans without specialty tiers charge coinsurance for all covered brand-name drugs, including drugs that tend to be placed by other plans on specialty tiers. Cost sharing for specialty drugs in these plans may actually be higher than that in plans with specialty tiers. Only one national PDP (First Health Part D Essentials) has no specialty tier in 2014, instead placing specialty drugs either on a non-preferred brand tier with 43 percent coinsurance or a preferred brand tier with 15 percent coinsurance.

Placing a drug on the specialty tier or on a non-preferred brand tier with high coinsurance can have serious cost implications for plan enrollees, at least before they reach the catastrophic coverage phase of the Part D benefit. A specialty drug priced at the $600 threshold will cost the beneficiary between $150 and $200 per month during the initial coverage period prior to the coverage gap. But monthly cost sharing for other common specialty drugs, such as Copaxone (for multiple sclerosis), Enbrel (for rheumatoid arthritis), Gleevec (for certain cancers), and Truvada (for HIV) can range from $300 to $2,000, before a beneficiary reaches the coverage gap or qualifies for catastrophic coverage. The cost for the first month of Sovaldi, a newly approved drug for hepatitis C, can exceed $5,000.7 For beneficiaries who use specialty drugs and exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold, the cost sharing is lowered to 5 percent of the drug cost for the remainder of the year.

Formularies and Utilization Management

In 2014, the average PDP enrollee is in a plan where the formulary lists 83 percent of all eligible drugs, the same as in 2013 but slightly below the average in prior years. The scope of formulary coverage, however, continues to vary widely across PDPs in 2014. Some plans list all drugs from the CMS drug reference file on their formularies, while other plans list as few as 63 percent of these drugs.8 Even the most limited formularies, however, exceed the formulary requirements established under law and CMS program guidance.9 The seven largest PDPs range in formulary coverage from 73 percent to 92 percent of drugs in the reference file. The average MA-PD plan enrollee is in a plan with slightly more drugs on formulary (87 percent) than PDPs. Beneficiaries retain the option of requesting an exception to have the plan cover an off-formulary drug, or they can obtain the drug by paying the full purchase price out of pocket.

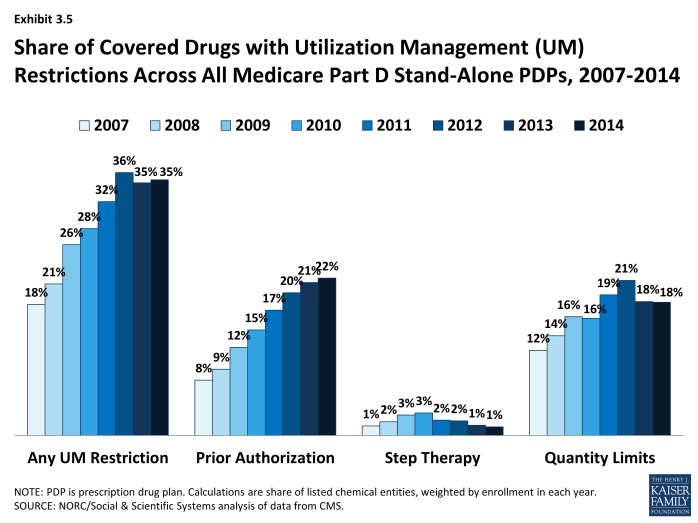

Since 2007, PDPs have applied utilization management (UM) restrictions to an increasing share of on-formulary drugs, increasing from 18 percent in 2007 to 35 percent in 2014 (Exhibit 3.5). Even if a drug is listed on a plan’s formulary, utilization management rules, including step therapy, prior authorization, and quality limits, may restrict a beneficiary’s access to the drug.10 In 2014, more drugs are subject to prior authorization than to other UM tools. On average across all PDPs (weighted for enrollment), prior authorization is applied to 22 percent of drugs. Quantity limits (e.g., limiting a prescription to 30 pills for 30 days) are applied to 18 percent of drugs in 2014, whereas only 1 percent of drugs are subject to step therapy. MA-PD plans tend to apply UM restrictions to a somewhat smaller share of drugs; in particular, they are less likely to apply quantity limits.

The Coverage Gap

In 2014, most PDPs (82 percent) offer little or no gap coverage beyond what is required by law; PDPs offering extra gap coverage cost more and have attracted fewer enrollees.11 In 2014, beneficiaries reaching the gap pay 47.5 percent of the full price for brand-name drugs in the gap (after a manufacturer price discount of 50 percent and plans paying 2.5 percent), and 72 percent of the cost for generics (plans pay the remaining 28 percent). Under current law, beneficiaries will face average cost sharing of only 25 percent for all drugs in the gap by 2020—the same as in the initial coverage period—effectively eliminating the coverage gap.

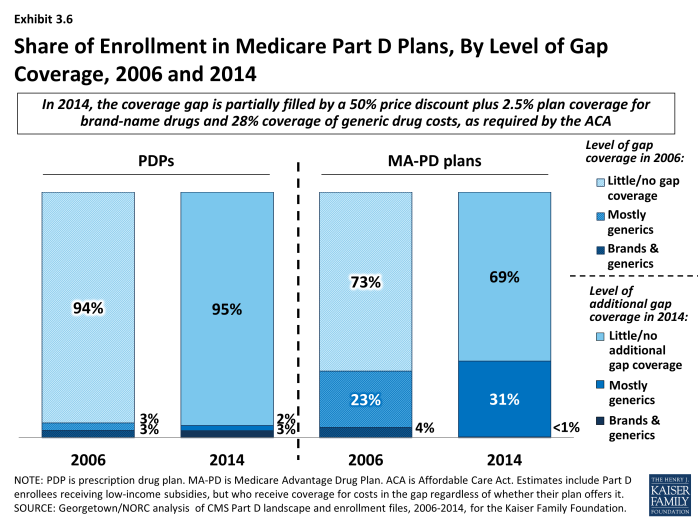

In 2014, 95 percent of all PDP enrollees are in plans without additional gap coverage beyond what is required by law (Exhibit 3.6). Overall, however, only 52 percent of PDP enrollees are potentially exposed to the gap in coverage if their spending exceeds the initial coverage limit. This lower percentage reflects the fact that LIS enrollees pay the same modest cost-sharing amounts in the gap as in the initial coverage period. In 2014, the vast majority of non-LIS Part D enrollees (92 percent) are enrolled in PDPs with no gap coverage beyond what is required by the ACA.

A similar share of MA-PD plans (22 percent) and PDPs (18 percent) offer additional gap coverage in 2014 for more than a “few” drugs, but a much larger share of MA-PD plan enrollees than PDP enrollees are in such plans.12 About one-third (31 percent) of MA-PD plan enrollees have at least some additional gap coverage beyond what the ACA requires, a modest increase since 2006 in the share with gap coverage, but considerably lower than the level of gap coverage in 2011 (43 percent) (Exhibit 3.6).13 The higher level of additional gap coverage among enrollees in MA-PD plans occurs largely because Medicare Advantage plans are able to use payments received from the government for providing benefits covered under Parts A and B to reduce cost sharing and premiums under Part D.14 Furthermore, because Medicare Advantage plans cover hospital and physician services and other Medicare benefits, they have stronger incentives than PDPs to offer at least some gap coverage to forestall the negative health and cost consequences that could arise if enrollees do not take their medications when they reach the gap. Despite these incentives, most MA-PD plans offer no additional gap coverage.

The vast majority of Part D enrollees with gap coverage (beyond that required by law) are in plans that cover only some generic drugs in the gap. In 2014, only about 3 percent of PDP enrollees and less than 1 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees have any significant gap coverage for brand-name drugs beyond the 50 percent discount and 2.5 percent payment that all plans must provide. Furthermore, gap coverage that includes all generic drugs (as opposed to a subset of generic drugs) has declined substantially over time. In 2014, only 7 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees and no PDP enrollees are in plans that cover all generics in the gap, compared to 28 percent and 3 percent in 2008.

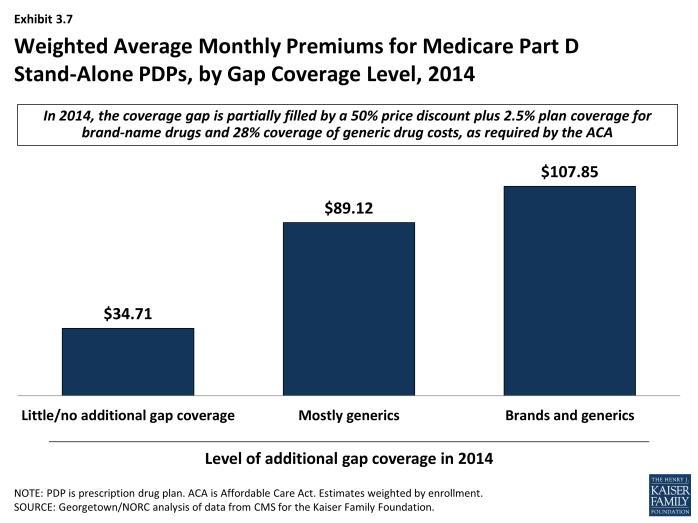

Enrollees in stand-alone Part D plans tend to pay substantially higher premiums for plans with gap coverage (beyond that which is required by law) compared to those without such coverage. On average, the weighted monthly premium for a stand-alone PDP offering additional gap coverage for generic drugs is $89.12, about $54 per month above that for plans offering no gap coverage (Exhibit 3.7).15 Plans with gap coverage for at least some brands are the most expensive, with average premiums of $107.85 for PDPs, which is about $19 per month higher than for PDPs covering only generics in the gap.

Preferred Pharmacy Networks

In 2014, 72 percent of all PDPs—representing 75 percent of all enrollees—have a preferred pharmacy network. By contrast, only 7 percent of PDPs (6 percent of enrollees) had a preferred pharmacy network in 2011 (Exhibit 3.8). Enrollees in these plans pay lower cost sharing for their prescriptions if they use preferred pharmacies.16 This new approach to plan design started in 2011 with the market entry of co-branded PDPs featuring relationships with specific pharmacy chains, such as the Humana Walmart-Preferred Rx PDP (new in 2011) and the Aetna CVS/Pharmacy PDP (new in 2012). Many other plan sponsors designated a preferred network in 2013 or 2014, mostly without a co-branded relationship. The idea behind these arrangements is that Part D plans are able to negotiate discounted prices at certain pharmacies in exchange for higher volume of sales. The lower cost sharing creates an incentive for enrollees to use the preferred pharmacies.

For most tiers, the median difference in cost sharing between filling a monthly prescription in a preferred pharmacy versus another network pharmacy is about $5. For example, in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP sponsored by UnitedHealth, the copayment for a preferred brand drug is $20 in a preferred pharmacy and $30 in another network pharmacy ($35 versus $50 for other brand drugs). Copayments in the Humana Preferred Rx PDP at a preferred pharmacy are $1 for drugs on the preferred generic tier and $2 for drugs on the non-preferred generic tier, compared to $4 and $6, respectively, at other network pharmacies. Coinsurance differences for this Humana PDP are 20 percent versus 25 percent for a preferred brand drug and 35 percent versus 41 percent for a non-preferred brand drug.

Although the difference in cost for filling a single prescription is modest, the financial consequences for non-LIS Part D plan enrollees if they do not use preferred pharmacies can add up for beneficiaries taking multiple brand-name drugs.17 An enrollee in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP who fills two brand drugs and one generic drug per month might pay an extra $252 over the year if she does not use one of the preferred pharmacies.

In 2013 (the most recent available data), PDPs with preferred pharmacy networks designated only about 30 percent of their network pharmacies as preferred.18 The share of preferred pharmacies in these PDPs ranged from 9 percent to 44 percent of network pharmacies. Overall, access to pharmacies is high. Most PDPs contract with at least 95 percent of all available pharmacies in their full pharmacy network. But generally plan sponsors do not offer the preferred terms to all pharmacies in their networks.

Limited information is available on the share of plan enrollees who fill prescriptions at preferred pharmacies. A CMS analysis of 2012 claims data found that the share of retail claims in preferred pharmacies ranged from 19 percent to 79 percent across 13 plans. For 7 of the 13 plans, the share of claims in preferred pharmacies was 37 percent or less.19

For some PDPs, access to preferred pharmacies is geographically limited. In some plans, there is no preferred pharmacy within a reasonable travel distance. A look at preferred pharmacies in 2014, using 14 sample zip codes, shows how the smaller network of preferred pharmacies affects beneficiaries. At a distance that corresponds roughly to how far consumers might expect to travel to a pharmacy,20 enrollees in the plans with preferred pharmacy networks typically find that a smaller share of local pharmacies are in the preferred networks: from zero percent to 22 percent of all network pharmacies, depending on the community. Furthermore, the level of access varies considerably by plan. Enrollees in the basic-benefit PDP with the most enrollees in 2014 (Humana’s Preferred Rx PDP) have no preferred pharmacy that is relatively close in 8 of the 14 sample zip codes and only one in the other six zip codes, whereas the second largest basic-benefit plan (UnitedHealth’s AARP Medicare Rx Saver Plus PDP) has no preferred pharmacy in only 3 of 14 zip codes. By expanding their potential travel distance, plan enrollees can reach more preferred pharmacies. But even at this greater distance, Humana’s PDP (which relies solely on Walmart pharmacies) still has no nearby preferred pharmacy in three urban zip codes.

In the call letter issued in April 2014, CMS indicated that it has contracted for a study of beneficiary access to different types of pharmacies.21 In addition, it will monitor pharmacy networks and take action against plan sponsors with too little meaningful access to the pharmacies that offer preferred cost sharing.

Premiums increased from 2013 to 2014 for nearly all PDPs with preferred pharmacy networks. Proponents of this new model of Part D plan point to lower premiums as a sign of their role in holding down Part D costs. One study found that preferred pharmacy networks could reduce federal spending considerably as a result of lower premiums.22 In fact, savings depend on the degree of discounts negotiated with pharmacies, the difference in cost sharing, and the share of beneficiaries who use the preferred pharmacies. Premium trends from 2013 to 2014, however, do not show clear evidence of savings. Whereas the average PDP premium fell by 2 percent from 2013 to 2014, all but one of the national or near-national PDPs with preferred pharmacy networks raised premiums, and most did so by at least 10 percent.

Section 3: Part D Benefit Design and Cost Sharing

exhibits

Section 4: The Low-Income Subsidy Program

Low-Income Subsidy Plan Availability

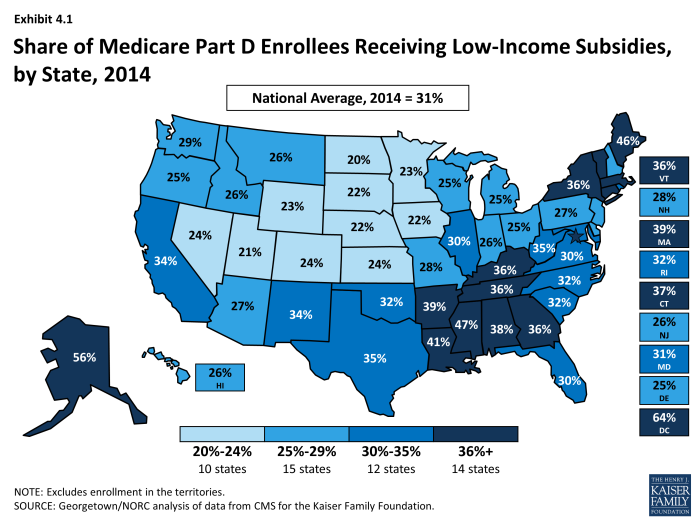

In 2014, 11.4 million Part D enrollees (30 percent of all Part D enrollees) were receiving the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS); of this total 8.3 million are enrolled in PDPs and 3.2 million in MA-PD plans. Most are deemed automatically eligible for the LIS based on being enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (or receiving benefits from Supplemental Security Income as well as Medicare). Based on data from 2009 (the most recent available data), only 16 percent obtain the LIS by applying under the program’s income and asset standards.1 The share of LIS enrollees varies considerably by state (Exhibit 4.1). In several of the more rural western states, between 20 percent and 25 percent of Part D enrollees receive LIS subsidies. By contrast, over 40 percent of Part D enrollees are receiving the LIS in Alaska, the District of Columbia, Louisiana, Maine, and Mississippi.

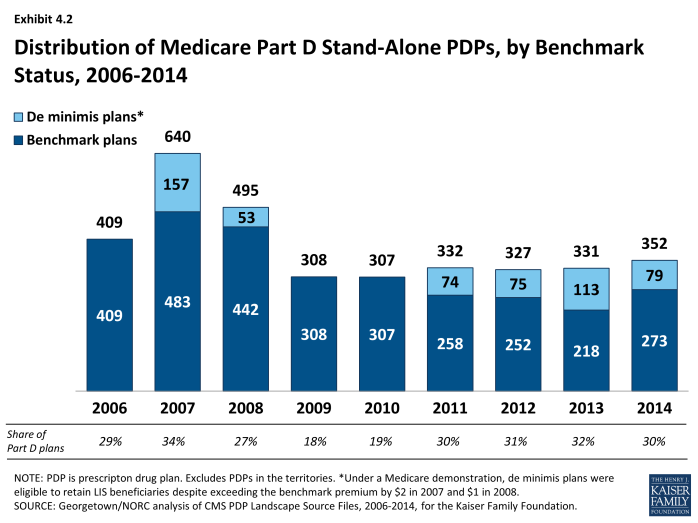

More “benchmark” plans—those available to beneficiaries receiving Part D Low-Income Subsidies for no monthly premium—are available in 2014 than in 2013, but they represent a marginally lower percentage of all PDPs in 2014. The total number of benchmark plans for LIS enrollees nationwide is 352 in 2014, an increase of 21 PDPs (6 percent) above the number in 2013 (Exhibit 4.2). Several policies in place since 2011, including the “de minimis” policy that allows plans to waive a premium amount of up to $2 in order to retain their LIS enrollees, has kept the number of benchmark plans from dropping. The number of LIS benchmark plans varies by region, ranging from 4 in Nevada to 15 in the Indiana/Kentucky region.

The benchmark plan market remains volatile, however. The benchmark plan market has changed considerably over the program’s eight years, which has generated significant instability for low-income enrollees. Of the 409 benchmark plans offered in 2006, only 13 plans have qualified as benchmark plans in every year since then. For a number of other plans, mergers interrupted continuous benchmark status, but the acquiring plan sponsor had a benchmark plan into which enrollees were transferred.2 Of the 331 benchmark plans available to LIS recipients for zero premium at the start of 2013, 46 lost benchmark status for 2014, a few more than between 2012 and 2013.3

As of the open enrollment period for the 2014 plan year (October 15 to December 7, 2013), one of every five LIS beneficiaries (1.9 million) were enrolled in benchmark PDPs in 2013 that failed to qualify as benchmark plans in 2014. To address this issue in part, CMS randomly reassigned about 392,000 PDP beneficiaries to PDPs operated by different sponsors for the 2014 benefit year (another 210,000 shifted to other PDPs operated by the same sponsors).4 Most of the others were not eligible for automatic reassignment by CMS because at some point they had switched plans on their own.

Premiums for Low-Income Subsidy Enrollees

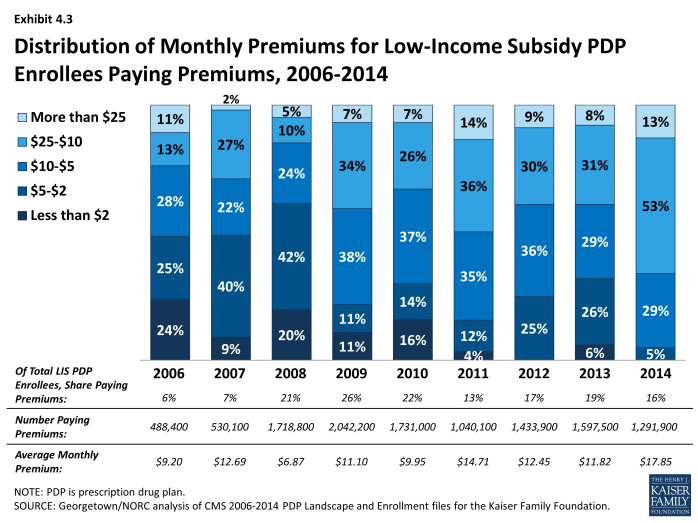

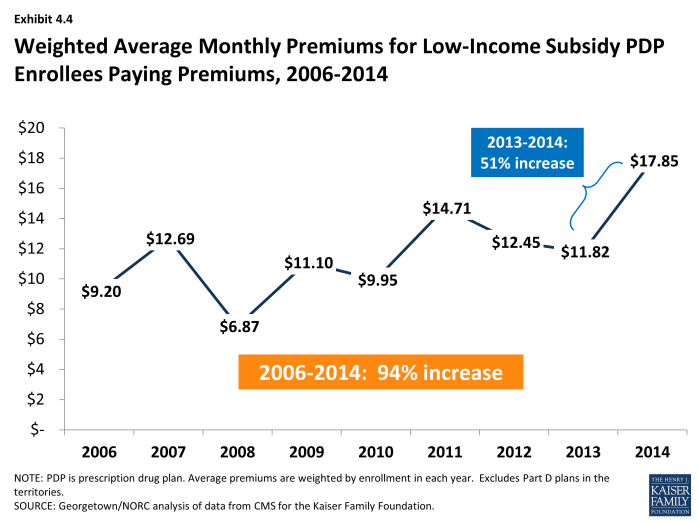

About 1.3 million LIS beneficiaries (16 percent of all LIS enrollees in PDPs) remain in non-benchmark PDPs in 2014 and are paying premiums for Part D coverage this year, a modest decrease from 2013 (Exhibit 4.3). The average monthly premium paid by these enrollees is $17.85—a 51 percent increase from 2013 (Exhibit 4.4). This amounts to over $200 annually in premium payments for beneficiaries whose incomes generally cannot exceed 135 percent of the federal poverty level. For beneficiaries not in benchmark plans, the federal government still pays the maximum subsidy amount for the beneficiary’s region of residence. But the government does not pay any amount above the benchmark, nor does it pay any portion of the premium that corresponds to enhanced benefits—even if the total Part D premium is below the benchmark.

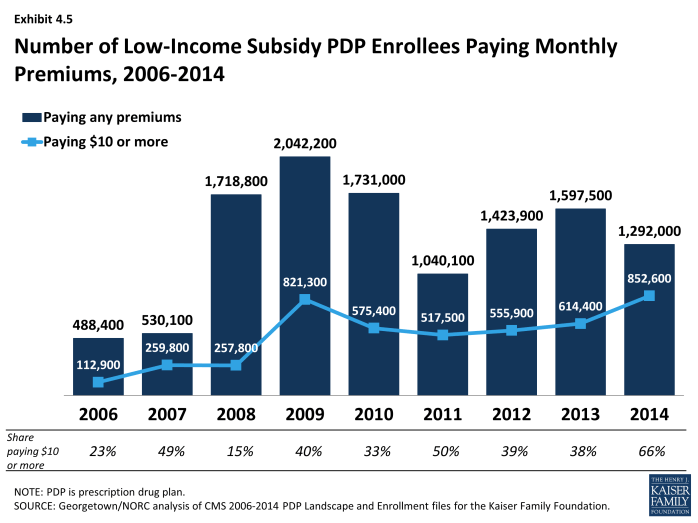

The proportion of LIS beneficiaries in PDPs paying premiums rose from 6 percent in 2006 to 26 percent in 2009, declined to 13 percent in 2011, but was back up to 16 percent in 2014 (Exhibit 4.5). About half of the LIS beneficiaries paying premiums in 2014 are enrolled in PDPs offered by UnitedHealth, mostly in the MedicareRx Preferred PDP, which lost benchmark status in all regions over the past two years. Depending on the region, these 634,000 UnitedHealth enrollees are paying from $4.70 to $26.90 per month.

In addition to the LIS enrollees who pay premiums for their PDPs, another 304,000 LIS beneficiaries enrolled in MA-PD plans pay a Part D premium. They represent 19 percent of all LIS beneficiaries enrolled in MA-PD plans (excluding those in Medicare Advantage plans designated as special needs plans, which are restricted to specific types of beneficiaries, such as those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid).

The de minimis premium waiver policy that allows 79 additional plans to qualify as benchmark PDPs helps many LIS enrollees avoid disruption. Without the de minimis premium waiver, about 1.2 million LIS beneficiaries in these PDPs (about one of every seven LIS enrollees) would either pay a small premium or would have been reassigned to different PDPs to avoid a premium.

About 853,000 LIS beneficiaries in PDPs are paying monthly premiums of $10 or more in 2014, representing about two-thirds of the 1.3 million LIS beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs who pay any premium (Exhibit 4.5). Another 135,000 LIS beneficiaries in MA-PD plans also pay premiums of $10 or more in 2014. It is possible that the LIS enrollees who pay a premium to enroll in these plans do so because of formulary or other individual considerations; another possibility, however, is that these enrollees are not reevaluating their plan options each year, even when it could save them money. It may be that they do not know that there are zero-premium plans available to them or have been unable to navigate the process of switching plans to avoid paying a premium.

Section 4: The Low-Income Subsidy Program

exhibits

Section 5: Part D Performance Ratings

More than two thirds (72 percent) of all PDP enrollees are in plans with average ratings (3 and 3.5 of 5 stars), and another 5 percent are in plans with ratings of four stars or higher; nearly one-fourth (23 percent) of PDP enrollees are in plans with below-average ratings (fewer than 3 stars) (Exhibit 5.1). CMS has reported performance ratings for Part D plans since the fall of 2006 and has used a five-star scale since the fall of 2008.1 In 2014, the Part D ratings are based on 15 measures in 4 categories. CMS has moved toward more use of outcome and patient experience measures (such as medication adherence for statins or diabetes medications), rather than process measures (such as call center performance). For 2014, the agency dropped three process measures (timeliness of enrollment transactions, ease of getting information from drug plan, and call center hold time for pharmacists), but did not add any new outcome measures. In contrast to the ratings for Medicare Advantage plans, however, CMS does not use quality ratings for Part D plans to determine bonus payments to these plans or to make plan assignments for LIS beneficiaries.

Overall Part D plan ratings in 2014 are up from 2013, but remain somewhat lower than in 2011. The degree to which differences reflect changing performance by the PDPs or modifications of the rating measures used by CMS is unclear. About 50 percent of PDPs have ratings of 3.5 stars or higher in 2014, compared to 39 percent of PDPs in 2013 and 56 percent of PDPs in 2011. Ratings in 2014 for MA-PD plans are much higher than for PDPs and are up from 2013.2 About 87 percent of MA-PD plans have drug plan ratings of 3.5 stars or higher in 2014, compared to 50 percent of PDPs. About 26 percent of MA-PD plans received 4.5 or 5.0 stars, compared to less than 1 percent of PDPs.

Based on the pattern of enrollment by plan ratings, there is little evidence to suggest that beneficiaries use ratings to guide their enrollment decisions. In 2014, the share of PDP enrollees in plans with relatively high ratings (3.5 stars or more)—60 percent—is somewhat higher than the share of PDPs (50 percent) with those ratings (Exhibit 5.1). However, an analysis of plan switching between 2009 and 2010 shows that enrollees in plans with at least 4 stars were actually more likely to switch than those in lower rated plans (16 percent versus 10 percent). It also shows that those who did switch plans were only slightly more likely to end up in a higher-rated plan (29 percent versus 20 percent).3 In a recent set of focus groups, most seniors on Medicare were not aware of the star ratings. Overall, they thought ratings could be helpful, but thought they were unlikely to be a major factor in their plan choice.4 More research is needed to determine the role of performance ratings on individual beneficiary choices.

Under current CMS policy, plans with ratings of less than three stars for three years in a row are subject to a special “low performance” flag on the Medicare Plan Finder website and may have their contracts terminated. Wellpoint has received this designation for the second straight year for its MedicareRx Rewards Standard and Plus PDPs (about 48,000 enrollees in 24 regions). Despite increasing its rating from 2 to 2.5 stars, the MedicareRx Rewards PDPs lost nearly 20 percent of their enrollees, perhaps as a result of this designation. CIGNA received this designation for the HealthSpring PDPs it acquired in 2012 (421,000 enrollees in 34 regions). In addition, three of the seven sponsors with PDP contracts in Puerto Rico have the “low performance” flag.

Starting in 2012, beneficiaries have been eligible at any time outside the regular open enrollment period to switch from their current drug plan to a PDP with a five-star rating (or a MA-PD plan with an overall five-star rating). In 2014, however, no PDPs have five-star ratings (only three PDPs had five stars in 2013). Among MA-PD plans, 47 plans with about 772,000 enrollees earned five stars. They include all 34 Kaiser Permanente plans and several smaller plans operating in five different states. Information is not available on how many people have used this special enrollment period, but aggregate monthly enrollment numbers suggest that most Part D enrollees have not acted on this option.

Section 5: Part D Performance Ratings

exhibits

Conclusion

Medicare Part D plans are an important source of prescription drug coverage for more than 37 million Medicare beneficiaries in 2014, the program’s ninth year. Participation in the program has grown more in recent years than in the first few years of the program, due to both increased enrollment of retirees in employer-only Part D plans and enrollment growth in Medicare as the baby boomers started reaching Medicare eligibility age in 2011.

Growth in average monthly Part D premiums has essentially flattened since 2010 after rising about 10 percent annually before then. Rising use of generic drugs, triggered by patent expirations for many popular brand-name drugs, has been a major factor in slowing premium growth—paralleling slower prescription drug spending growth in the broader health system.1 The result has been savings for both the government and Part D plan enrollees. However, both CBO and Medicare’s Office of the Actuary are projecting higher growth in drug spending in the future as the rate of patent expirations slows and as new drugs, including new treatments for hepatitis C, enter the market at prices far beyond those for older brand-name drugs.2

Plan premiums vary substantially across regions and across different plans offered in each region. Beneficiaries in the region with the highest premiums pay monthly premiums that are twice as high, on average, as those in the region with the lowest premiums. And even within a region, among PDPs offering benefit packages having the same value, beneficiaries can pay five times as much in monthly premiums for one PDP compared to another. Despite these wide variations and large year-to-year increases for some of the program’s most popular plans, most enrollees remain in the same plan from one year to the next. In fact, seven of ten enrollees never changed plans across four annual enrollment periods from 2006 to 2010.3

Enrollees have continued to face higher cost sharing for brand-name drugs, although many plans in recent years have lowered cost sharing for generic drugs, thus increasing incentives to select generics.4 A growing number of PDPs are switching from flat copayments to percentage-based coinsurance for brand-name drugs, and nearly all plans use coinsurance for specialty drugs. Many beneficiaries who use these expensive drugs will pay much lower coinsurance when they reach the catastrophic benefit phase than in the initial coverage period. But high initial cost sharing can deter enrollees from starting treatment with a new medication, meaning they never reach the out-of-pocket spending threshold that qualifies them for catastrophic coverage.

The Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program continues to represent a significant source of savings for qualifying beneficiaries. But the continuing volatility of the PDP offerings available without a premium to LIS beneficiaries remains a concern. CMS assigned nearly 400,000 LIS beneficiaries to new plans in 2014, thus protecting their full LIS benefits but potentially resulting in disruptions in coverage. Nevertheless, 1.3 million LIS enrollees in PDPs and another 300,000 in MA-PD plans are paying monthly premiums for Part D coverage when they could be in zero-premium drug plans, including nearly one million LIS beneficiaries paying premiums of at least $10 per month in 2014.

A major new trend, starting in 2011, has been the introduction of preferred pharmacy networks—with lower cost sharing in a select set of pharmacies and higher cost sharing elsewhere. As of 2014, three-fourths of PDP enrollees are in these plans. But some beneficiaries in these plans may find that no preferred pharmacy is located near their homes. CMS is reviewing options for ensuring that beneficiaries have adequate access to the preferred pharmacies. Several PDPs that feature preferred pharmacy networks entered the market with low premiums, but premiums for those plans rose rapidly in subsequent years.

The Part D program has undergone various modifications in recent years. Part D enrollees have benefited from lower out-of-pocket costs on both brand-name and generic drugs in the gap because of changes specified in the 2010 Affordable Care Act. Ongoing efforts by CMS to streamline the program have led to a smaller and better-defined set of plan options for Part D enrollees. CMS has also strengthened the plan performance rating system, though there is little evidence that ratings play a significant role in plan selection. Fewer than one in ten PDP enrollees are in plans with at least 4 stars (out of 5), and nearly one-fourth are in PDPs with fewer than 3 stars—a level considered low performance.

One key measure of success of the Part D program is that it has increased the availability of prescription drugs among Medicare beneficiaries at a lower out-of-pocket cost than in the absence of drug coverage. This increased access has occurred as Part D program spending has come in considerably below the government’s original expectations. The Part D marketplace remains dynamic, however, with mergers continuing to reshape the market and changes affecting plan availability for Low-Income Subsidy beneficiaries.

Jack Hoadley and Laura Summer are with the Health Policy Institute, Georgetown University; Elizabeth Hargrave is with NORC at the University of Chicago;

Juliette Cubanski and Tricia Neuman are with the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Methodology

- Plan “landscape” files, released each fall prior to the annual enrollment period. These files include basic plan characteristics, such as plan names, premiums, deductibles, gap coverage, and benchmark plan status.

- Plan premium files, also released each fall. These files include more detail on plan characteristics, including premiums charged to LIS beneficiaries, the portions of the premiums allocated to the basic and enhanced benefits, and the separate drug premiums for MA-PD plans.

- Plan crosswalk files, also released each fall. These files identify which plans are matched up when a plan sponsor changes its plan offerings from one year to the next.