Medicare Part D at Ten Years: The 2015 Marketplace and Key Trends, 2006-2015

Jack Hoadley, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman

Published:

Executive Summary

Since 2006, Medicare beneficiaries have had access through Medicare Part D to prescription drug coverage offered by private plans, either stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MA-PD plans). Now in its tenth year, Part D has evolved due to changes in the private plan marketplace and the laws and regulations that govern the program. This report presents findings from an analysis of the Medicare Part D marketplace in 2015 and changes in features of the drug benefit offered by Part D plans since 2006. Key findings are summarized below.

Key Findings

Part D Enrollment and Plan Availability

In 2015, more than 39 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare drug plans. Since 2006, the share of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in a Part D plan has increased from 53 percent to 72 percent of all eligible Medicare beneficiaries.

- The majority (61 percent) of Part D enrollees are in PDPs, but enrollment in MA-PD plans is growing more rapidly. MA-PD plan enrollment accounts for two-thirds of the net increase in Part D enrollment from 2014 to 2015, and the share of MA-PD enrollment has grown over the past decade from 28 percent to 39 percent.

- In 2015, 6.6 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in an employer-only Part D plan designed solely for retirees of a former employer. Enrollment in employer-only Part D plans has quadrupled since 2006.

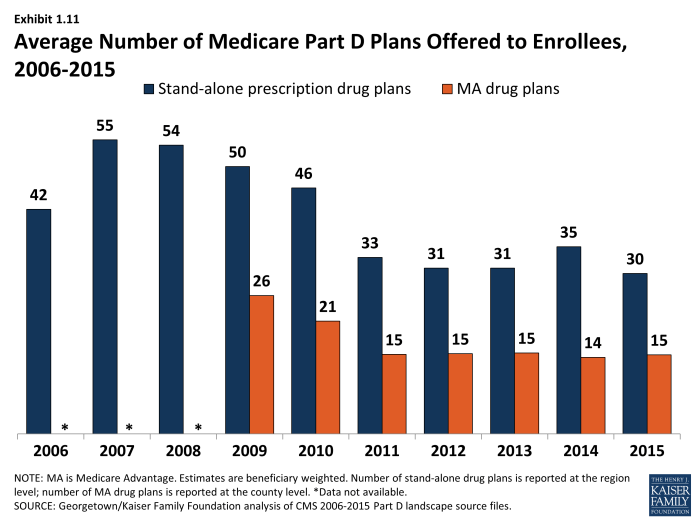

The average Part D enrollee had a choice of 30 PDPs and 15 MA-PD plans in 2015.

- The average number of PDPs offered to enrollees has dropped from a high of 55 plans in 2007 to 30 plans in 2015. Between 2014 and 2015, the average number of PDPs offered to enrollees dropped from 35 to 30 plans, while the number of MA-PD plans per enrollee increased slightly from 14 to 15 plans.

In 2015, three Part D sponsors account for half of all Part D PDP and MA-PD enrollees.

- UnitedHealth, Humana, and CVS Health have enrolled half of all participants in Part D. This level of market concentration is relatively unchanged since 2006. UnitedHealth and Humana have topped enrollment since the program began, while enrollment in CVS Health has grown through acquisition of other plan sponsors. UnitedHealth, by itself, has maintained the top position for all ten years of the program, and in 2015 provides coverage to more than one in five PDP and MA-PD enrollees.

Part D Premiums

Average monthly PDP premiums have been essentially flat since 2010; MA-PD premiums have risen modestly in the past few years.

- PDP enrollees pay $37.02 per month, on average, in 2015, whereas enrollees in MA-PD plans pay only $17.29.The combined average for PDP and MA-PD plan enrollees is $30.02 in 2015.

Premiums for some of the most popular plans increased in 2015, while for others, premiums fell.

- Humana’s Walmart Rx PDP, which was new in 2014, raised its premiums by 24 percent (an average increase of about $3 per month) in 2015. By contrast, the SilverScript Choice PDP lowered its premium by 21 percent (an average decrease of about $6 per month) in 2015.

PDP premiums vary widely across plans and across regions.

- Premiums vary for plans with equivalent benefits, ranging from $12.60 to $101.40 per month for plans offering the basic Part D benefit.

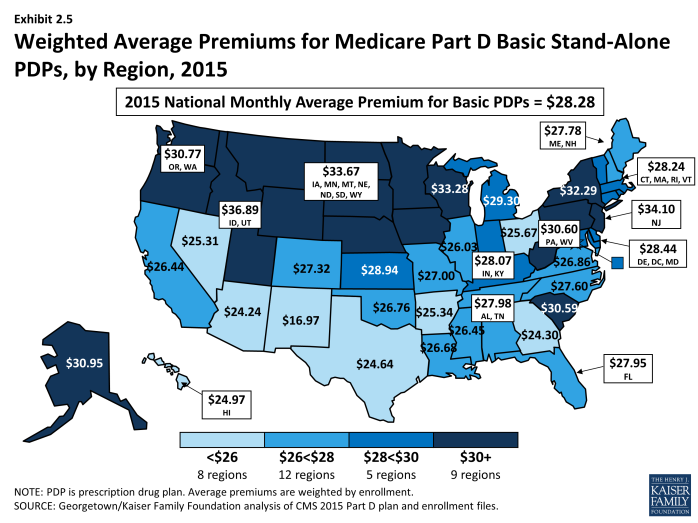

- One source of variation is geographic differences. Average PDP premium for plans with the basic benefit are $16.97 in New Mexico and $36.90 in the Idaho/Utah region.

Part D Benefit Design and Cost Sharing

In 2015, most plans use five cost-sharing tiers: preferred and non-preferred tiers for generic drugs, preferred and non-preferred tiers for brand drugs, and a tier for specialty drugs.

- The vast majority of all Part D enrollees (80 percent of PDP enrollees and 91 percent of MA-PD enrollees) are in plans that use five cost-sharing tiers, a design that gained popularity starting in 2012.

Cost sharing for brand-name drugs has been relatively stable in recent years, but has risen substantially since the start of Part D; MA-PD plan enrollees generally pay somewhat higher cost sharing than PDP enrollees.

- Cost sharing for brands increased between 2006 and 2015 by about 36 percent for beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs and by nearly 70 percent for those in MA-PD plans. In the same period, cost sharing for generics decreased.

- On average, MA-PD plan enrollees pay somewhat higher cost sharing for their drugs than PDP enrollees, particularly for brand-name drugs. For example, median cost sharing for preferred and non-preferred brands in MA-PD plans is $45 and $95, respectively, compared to $38 and $80 in PDPs.

- Copayments for brand-name drugs are higher than those typically charged by large employer plans, while copayments for generics are lower.

- In 2015, many PDP enrollees are in plans that charge coinsurance instead of copayments: 28 percent of enrollees face copayments for preferred brand drugs and 63 percent for non-preferred brand drugs.

Nearly all Part D plans use specialty tiers for high-cost drugs and charge coinsurance of 25 percent to 33 percent during the benefit’s initial coverage period.

- Nearly half of all PDP enrollees and nearly three quarters of all MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans that charge the maximum 33 percent for these high-cost drugs.

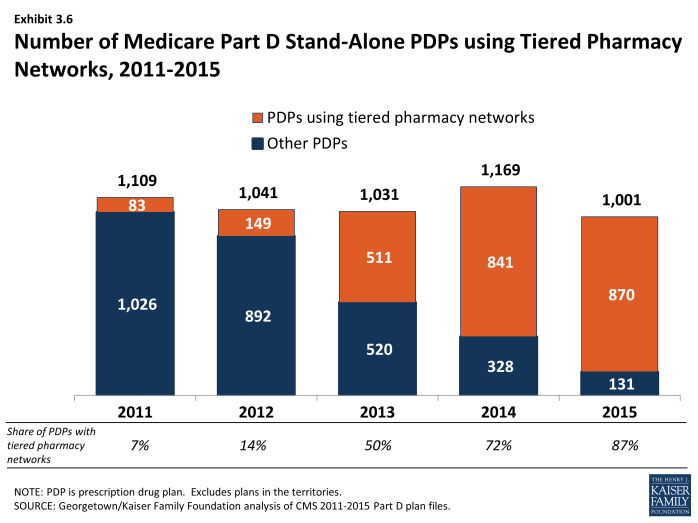

The use of tiered pharmacy networks has grown rapidly in recent years and is now the norm in PDPs.

- The share of Part D stand-alone drug plans with tiered pharmacy networks grew from 7 percent in 2011 to 87 percent in 2015. Enrollees in these plans pay lower cost sharing if they use pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing and higher cost sharing if they use other pharmacies.

Low-Income Subsidy Program

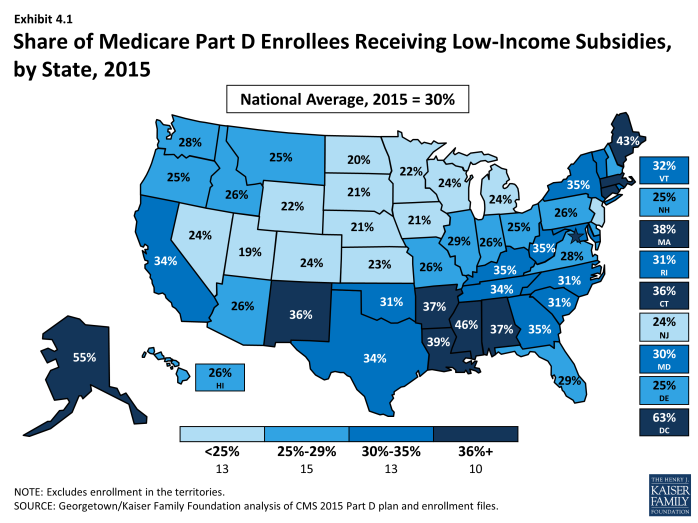

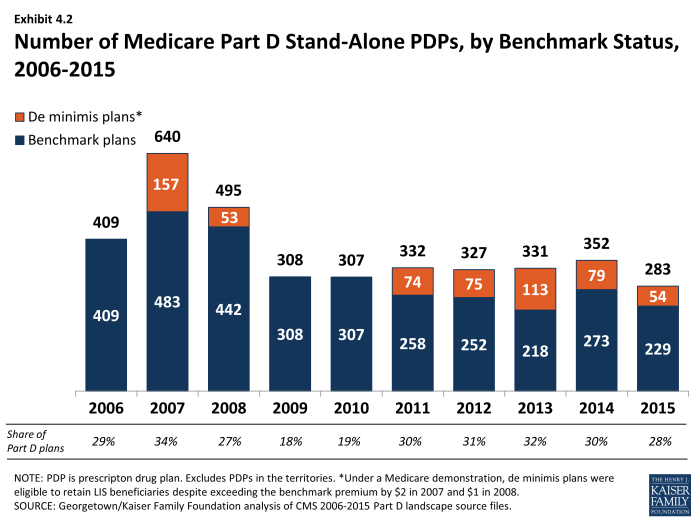

- About 11.7 million Part D enrollees (30 percent) receive extra help through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), a majority of whom (8 million) are enrolled in stand-alone PDPs. The subsidy reduces cost sharing and pays their drug plan premiums, as long as they enroll in PDPs designated as benchmark plans.

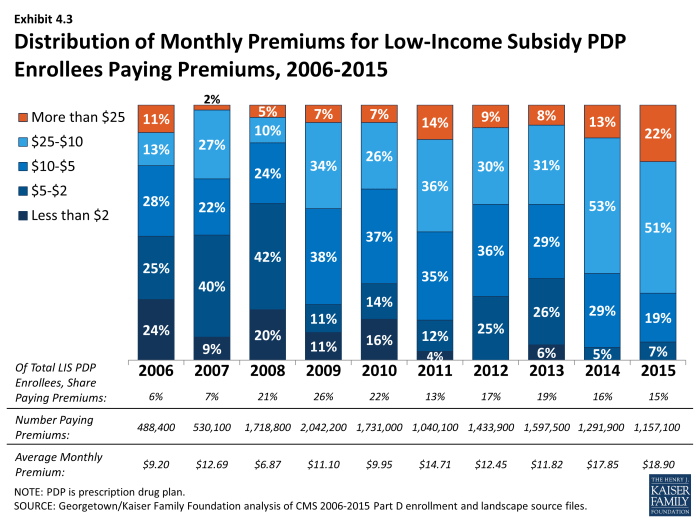

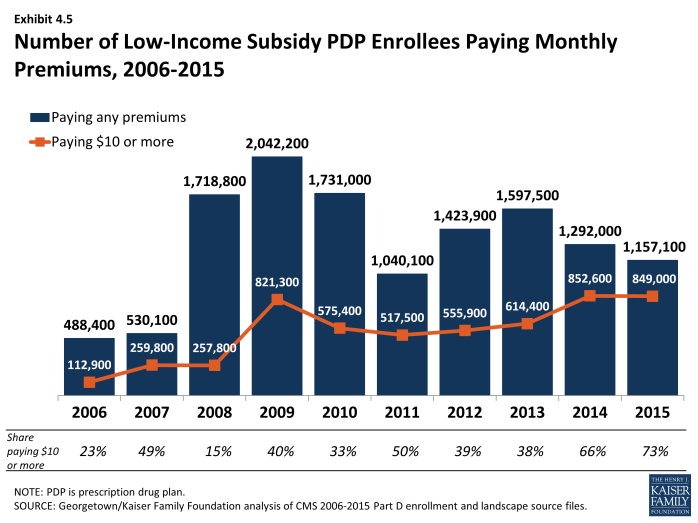

- In 2015, 15 percent of LIS beneficiaries enrolled in PDPs (1.2 million) are paying monthly premiums, and of this group, three-fourths are paying $10 or more per month. In addition, 381,000 LIS beneficiaries enrolled in MA-PD plans are paying premiums in 2015. CMS does not reassign these beneficiaries to a zero-premium PDP because they have actively selected the plan they are in.

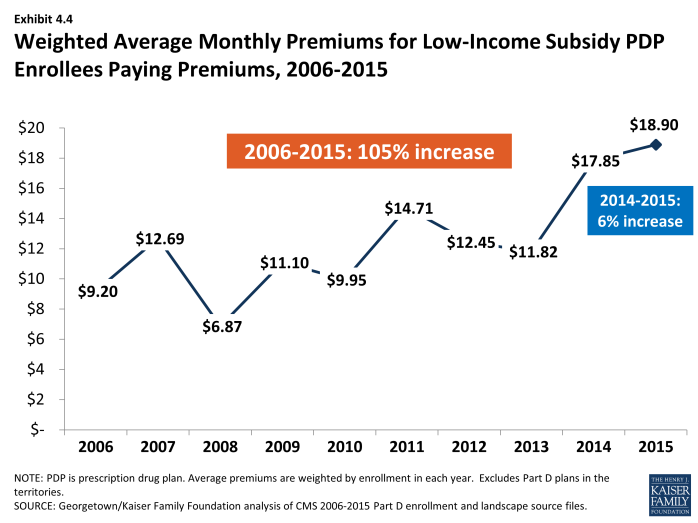

- On average, LIS beneficiaries paying premiums for their PDPs pay $18.90 per month, well above the average in previous years.

- Part D Plan Performance Ratings

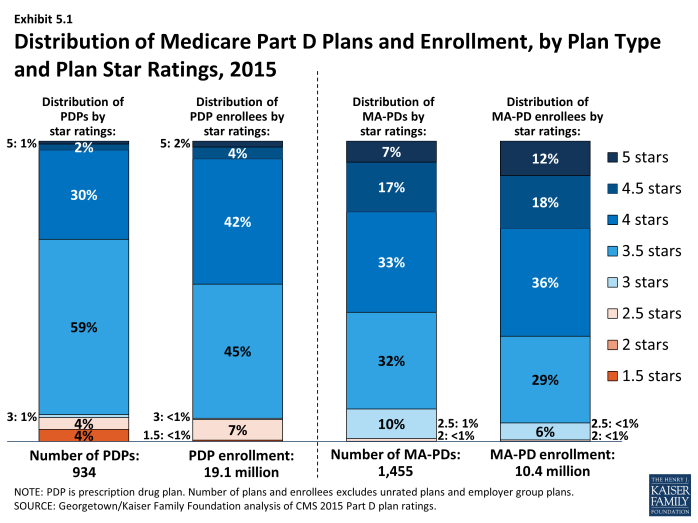

Nearly half of PDP enrollees are in plans with the highest star ratings (4 stars or more).

- Part D plan ratings in 2015 are up considerably from 2014 levels. The share of PDP enrollees in plans with at least four stars out of a maximum five stars rose from 5 percent in 2014 to 48 percent in 2015.

Discussion

Now in its tenth year of operation, the Part D program has experienced relative stability in recent years. The program has had consistently high levels of plan participation, offering dozens of plan choices for beneficiaries in each region and broad access to generic and brand-name drugs. While the Part D program has matured since 2006, the marketplace also changes every year. Plans can and do enter and drop out of the market annually, and enrollees can and do experience changes in premiums, cost sharing for their medications, which drugs are covered by their plan, and which pharmacies they can use without paying higher cost sharing.

Beneath the surface, there are trends that could pose cost and access challenges for Part D enrollees. At a time of heightened public concern about the cost of prescription drugs, median cost sharing for brand-name drugs has increased over the years and more plans impose coinsurance for brand tiers. Although premiums have been flat in recent years, the high cost of newly approved drugs and others in the pipeline could change that trend. In the absence of an absolute limit on out-of-pocket costs, Part D enrollees with high drug use could face growing out-of-pocket costs.

Introduction

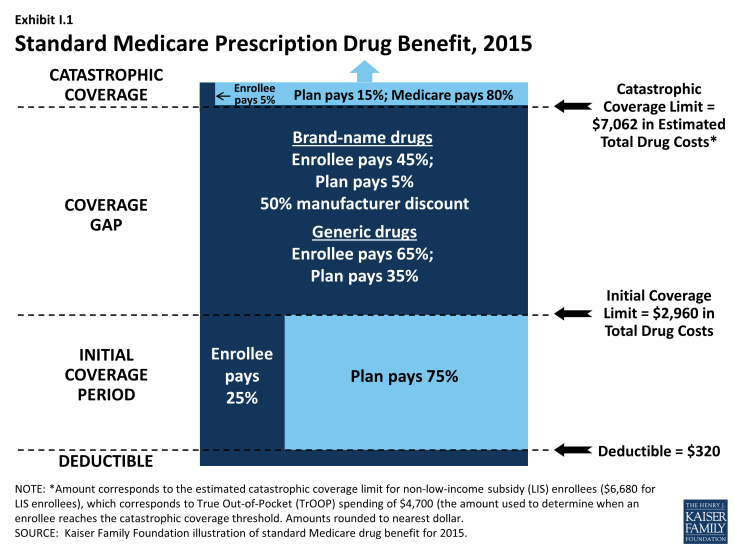

Since 2006, Medicare beneficiaries have had access to prescription drug coverage offered by private plans, either stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MA-PD plans). These Medicare drug plans (also referred to as Part D plans) receive payments from the government to provide Medicare-subsidized drug coverage to enrolled beneficiaries. Part D plans are required to offer a defined standard benefit or one that is equal in value (Exhibit I.1). They may also offer an enhanced benefit. Medicare drug plans must meet defined requirements, but may vary in terms of premiums, benefit design, gap coverage, formularies, and utilization management rules.

In 2015, more than 39 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare drug plans, including 24 million in PDPs and 15 million in MA-PD plans.1, 2 About 12 million Part D enrollees are receiving extra help through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program to pay their drug plan premiums and cost sharing. Part D has evolved since its inception in 2006 due to changes in the private plan marketplace and the regulations that govern the program. The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) is bringing significant improvements to the program, primarily phasing out the coverage gap, or “doughnut hole,” in the drug benefit.3 In addition to a 50 percent manufacturer discount on the price of brand-name drugs in the gap, the law further reduces cost sharing for brand-name and generic drugs in the gap over time, reducing cost sharing to the level that applies before the gap and eliminating the coverage gap in 2020. In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has implemented other statutory and regulatory changes that have resulted in some consolidation of Part D plan offerings, along with a degree of greater standardization.

This report presents findings from an analysis of the Medicare Part D marketplace in 2015, the program’s tenth year, and changes in various features of the drug benefit since 2006.4 It presents key findings in five different areas:

- Enrollment and plan availability;

- Premiums;

- The design of Part D benefits, including cost sharing, specialty tiers, formularies, utilization management, the coverage gap, and tiered pharmacy networks;

- The Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program for low-income beneficiaries; and

- Plan performance ratings.

The findings are based on data from CMS for all plans participating in Part D. More detail about the methods used in this analysis is provided on page 53.

Key Findings

Section 1: Part D Enrollment and Plan Availability

Beneficiary Participation in Part D

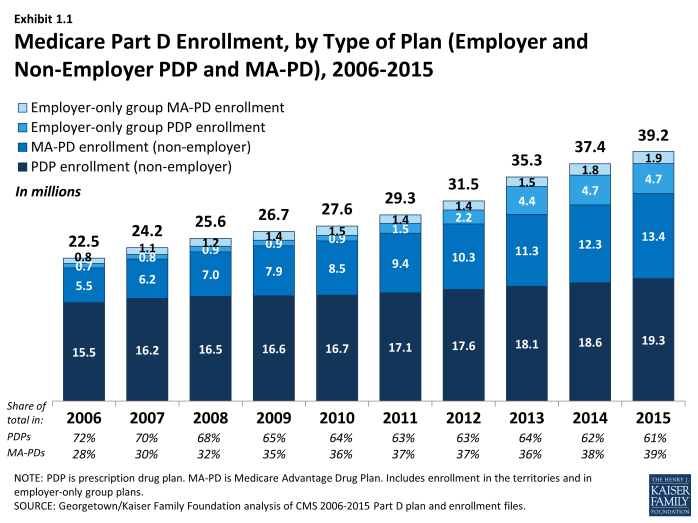

More than 39 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a Part D plan, either a PDP or MA-PD in 2015, representing 72 percent of all eligible Medicare beneficiaries. This is an increase of nearly 2 million beneficiaries since 2014 and of nearly 17 million beneficiaries since 2006 when only 53 percent of eligible beneficiaries were enrolled in Part D plans (Exhibit 1.1). In 2006, a larger share of Medicare beneficiaries received drug coverage from other sources such as former employers, so that a total of 90 percent of beneficiaries had coverage for their drugs from some source.1 In 2012 (the most recent year for which data are available), 88 percent had drug coverage at least comparable to Part D coverage and 12 percent of Medicare beneficiaries had no drug coverage whatsoever.2

More than half of the ten-year increase comes from additional enrollment in MA-PD plans, which is likely a mix of enrollees new to Part D or to Medicare altogether and those who switched from traditional Medicare supplemented by PDP coverage to MA-PD plans.3 The rest of the increase is a mix of higher PDP enrollment and more enrollment in employer-only Part D plans. About two-thirds of the increase from 2014 to 2015 is from enrollment gains for MA-PD plans.

The 4.8 percent enrollment increase from 2014 to 2015 is lower than some earlier years. Growth was higher in 2007 and 2008 as the program ramped up and higher again in 2012 and 2013 as a result of increased enrollment of retirees in employer-only Part D plans. Over ten years, the average annual rate of increase is 6.4 percent.

The share of Medicare beneficiaries with Part D coverage varies by state, ranging from 38 percent (Alaska) to 77 percent (Michigan) (Exhibit 1.2). States with the highest shares of Part D enrollment are California, Michigan, New York, and Ohio, each with 75 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in Part D. Alaska, Maryland, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia have fewer than 60 percent of their residents on Medicare in Part D plans. Some of these states have high shares of federal employment; federal retirees get drug coverage outside Part D through the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program.

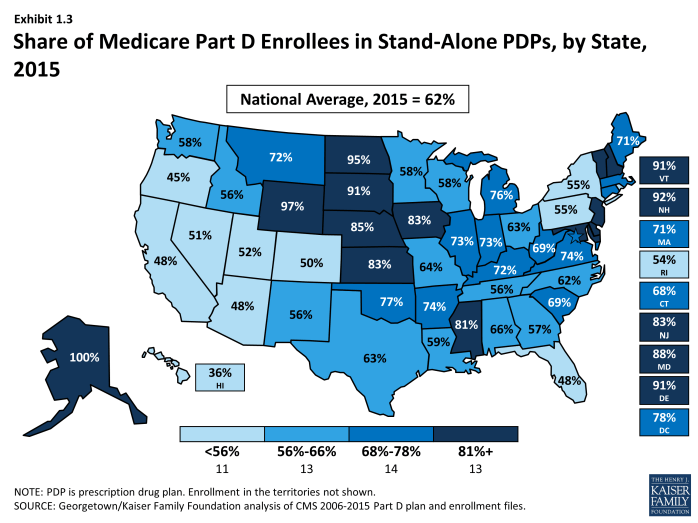

Nationally, about 61 percent of Part D enrollees are in PDPs; the remaining 39 percent are in MA-PD plans, with considerable variation by state (Exhibit 1.2), Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2. PDP enrollment accounted for 72 percent of total enrollment in 2006, but this share has been declining over time as MA-PD plan enrollment has grown more rapidly than PDP enrollment in recent years. From 2006 to 2015, non-employer MA-PD plan enrollment grew by 10.5 percent annually, whereas non-employer PDP enrollment grew by only 2.4 percent annually. The more rapid growth in MA-PD enrollment from 28 percent to 39 percent of Part D enrollees reflects the broader trend of greater enrollment in Medicare Advantage.

PDPs account for 100 percent of Part D enrollees in Alaska and more than 90 percent of enrollees in six other states with low populations (Delaware, New Hampshire, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming). By contrast, MA-PD plans account for half or more of Part D enrollees in five states: Arizona, California, Florida, Hawaii, and Oregon.

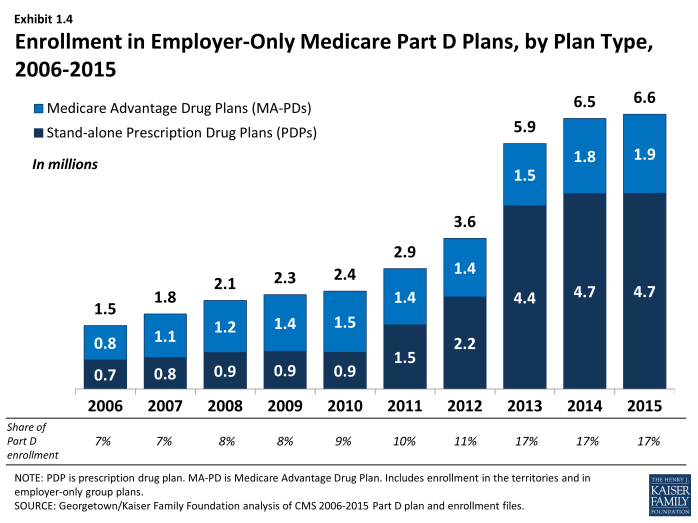

Between 2011 and 2013, total enrollment in employer-only Part D plans doubled from 2.9 million to 5.9 million beneficiaries, rising more modestly to 6.6 million in 2015 (Exhibit 1.4), Appendix Table 2). Total enrollment in employer-only Part D plans in 2015 is more than four times the level in 2006. The biggest increase was between 2012 and 2013, when enrollment in these plans grew 63 percent. The growth rate slowed to less than 1 percent in 2015.

The major impetus for this growth was a provision in the ACA that eliminated the tax deductibility of the 28 percent Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS), effective in 2013.4 This subsidy, paid to employers who provide creditable prescription drug coverage to Medicare beneficiaries, was included in the original Part D legislation to encourage employers to maintain existing drug coverage for their retirees. In 2006, 7.2 million Medicare beneficiaries were covered in retiree health plans that received the RDS (with an average subsidy payment of $527 per person in 2006, rising to a projected $625 in 2015). With the changed tax status of the RDS, enrollment in subsidized retiree plans dropped to 2.7 million in 2014, and the Medicare Trustees project a drop to 2.2 million in 2015 and 0.9 million by 2019.5

Most employers that no longer elected to receive the subsidy after the change in tax treatment have shifted their retirees to employer-only Part D plans. Most of the new enrollment was in employer-only PDPs. In 2013, enrollment was up 99 percent in employer-only PDPs and just 7 percent in employer-only MA-PD plans. In 2014 and 2015, as growth in employer plans slowed overall, there was a modest shift toward MA-PD plan enrollment.

Continuity of Part D Plan Offerings

About one-fifth of the PDPs that participated in Part D in its first year are still in the market today. There are 315 PDPs operating under the same contract and plan identification number in 2015 as in 2006. About one-fourth of these PDPs operate under the same plan name, while others have similar names. For example, what was originally the AARP MedicareRx Plan, sponsored by UnitedHealth, is now called AARP MedicareRx Preferred. Others have changed as a result of acquisitions; for example, five PDPs offered by Sterling in 2006 are now known as WellCare Simple PDPs. About one-fourth of these continuously operating PDPs have changed their benefit type; in most cases, PDPs originally offering the basic benefit now operate as enhanced benefit PDPs (a change in status no longer allowed by CMS).

These continuously operating PDPs accounted for about 44 percent of all PDP enrollees in 2006, and 55 percent of total enrollment in 2015. Most of the remaining PDP enrollees are in other plans offered by sponsors that have participated in Part D since 2006. Of the six plan sponsors that entered the Part D market after the program’s first year, none have attracted a significant market share. The most successful new entrant has been Envision RxPlus, which held a 2.5 percent share of PDP enrollment in 2013, declining to 2 percent in 2015.

Firm Participation

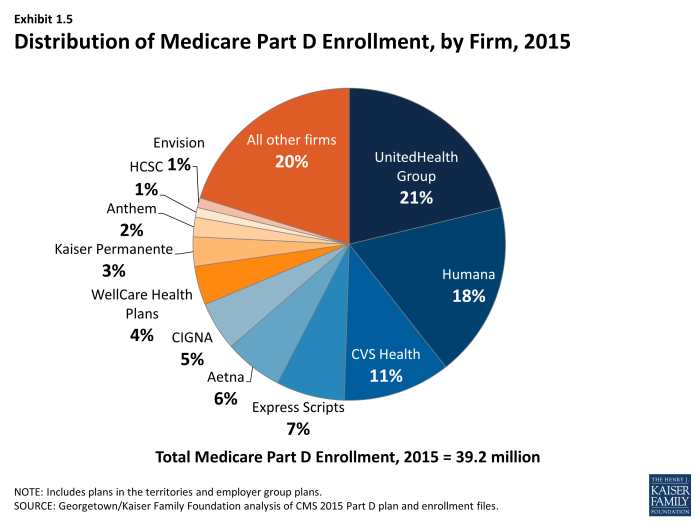

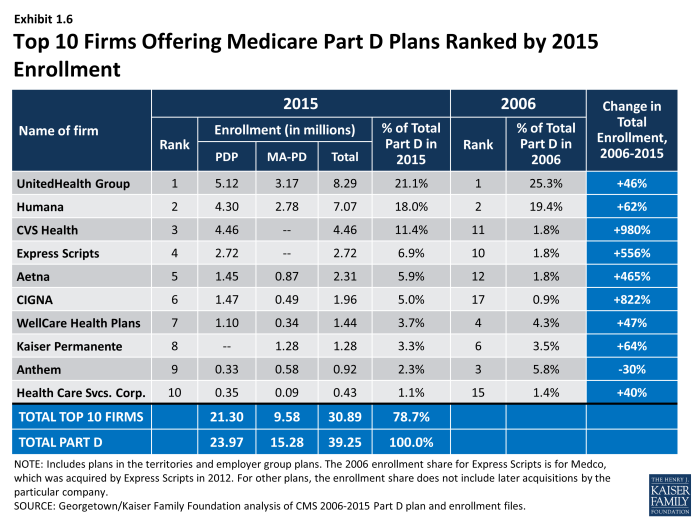

In 2015, the ten largest sponsors of Part D plans account for more than three-fourths of all enrollees, three firms account for half of all enrollees, and UnitedHealth alone accounts for more than one in five Part D enrollees (including 21 percent of PDP enrollees and 20 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees) (Exhibit 1.5).6 This pattern of a few plan sponsors having a substantial share of Part D enrollment has held over the program’s first ten years. The ten largest Part D plan sponsors in 2015 have enrolled 30.9 million beneficiaries in either a stand-alone PDP or an MA-PD plan (Exhibit 1.6).7 The share of enrollment in the ten largest plans in 2015 (79 percent) is higher than in 2006 (69 percent). In 2006, the top three firms also accounted for about half of all enrollees. Four firms that were in the top ten for 2006 have been acquired during the intervening years: three by CVS Health and one by Aetna.

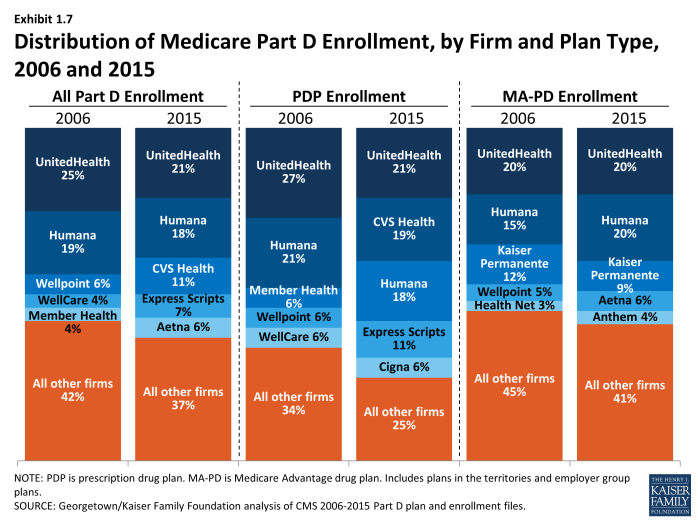

Patterns are similar for the PDP and MA-PD plan markets, viewed separately (Exhibit 1.7). In the PDP market alone, the top three sponsors (UnitedHealth, CVS Health, and Humana) account for nearly 60 percent of enrollment in 2015—slightly more than the 54 percent share held by the top three sponsors (UnitedHealth, Humana, and Member Health) in 2006. Among MA-PD plans, UnitedHealth and Humana each have 20 percent of the market in 2015, followed by Kaiser Permanente, with 9 percent; these are the same three sponsors that held the most MA-PD market share in 2006.

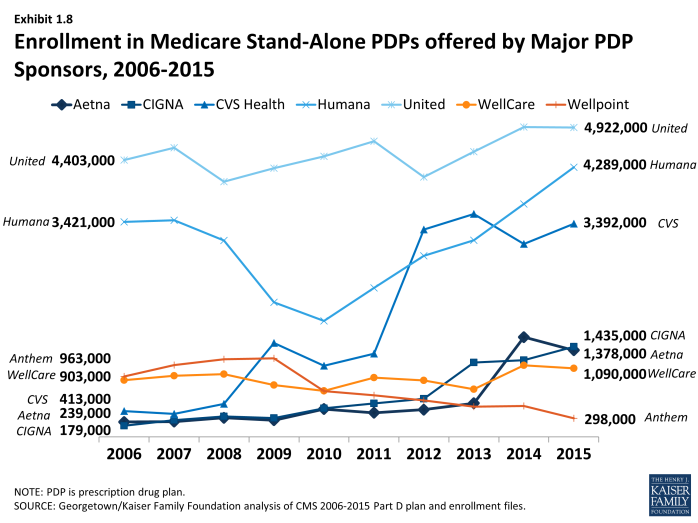

The growth pattern among the largest PDP sponsors illustrates some of the different strategies used since the start of the program (Exhibit 1.8). UnitedHealth has been the largest PDP sponsor since 2006, and Humana has generally been the second largest. CVS Health has used an acquisition strategy to move solidly into the third position. Aetna and Cigna have moved higher up in recent years, also through acquisitions. It is noteworthy that both acquiring firms in recently proposed mergers (Aetna and Anthem) lost enrollment in the PDP market from 2014 to 2015, whereas both firms to be acquired (Humana and Cigna) gained enrollment.

Seven of the top ten firms in 2015 sponsor both stand-alone PDPs and MA-PD plans. Kaiser Permanente is the only sponsor among the top ten that offers only MA-PD plans, and Anthem is the only other firm with more MA-PD enrollees than PDP enrollees. CVS Health and Express Scripts offer only PDPs. Other than Kaiser Permanente and Anthem, at least 60 percent of each of the top firms’ enrollment is in PDPs.

Enrollment growth since 2006 for CVS Health, Express Scripts, Aetna, and Cigna is due largely to acquisitions of other plan sponsors. CVS Health has used an acquisitions strategy to become the third largest sponsor in the Part D marketplace. The parent company now includes 5 of the 18 firms that had the most enrollees in 2006. Cigna and Aetna have grown their Part D market shares through similar acquisitions strategies. Express Scripts has grown both through its recent acquisition of Medco, but also through the overall increase in enrollment in employer-only plans since the RDS tax status change. Four plan sponsors dominate the employer-only segment of the Part D market, collectively accounting for about two-thirds of all enrollees in employer-only Part D plans: Express Scripts (34 percent), CVS Health (16 percent), UnitedHealth (10 percent), and Kaiser Permanente (7 percent).

National plan sponsors have dominated the Part D PDP market from the start. Firms serving all or most regions hold 94 percent of the PDP market in 2015, up from 89 percent from 2006. Most other sponsors with plans in no more than a few regions are local Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) plans. Among the PDPs serving no more than a few regions, the only non-Blue plan with a PDP market share of greater than 1 percent in a region is the WPS Insurance Company, a not-for-profit plan sponsor with 7 percent of the market in Wisconsin. BCBS plans with large market share in their regions are the coalition of BCBS plans in the seven-state upper Midwest region (23 percent), the Health Care Service Corporation affiliates in Illinois (21 percent) and Oklahoma (14 percent), Arkansas BCBS (14 percent), the coalition of BCBS plans in southern New England (11 percent), and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas (10 percent). Five regions have no PDP sponsored by a BCBS plan.

UnitedHealth and Humana have been the two largest Part D plan sponsors from the start of the program, but their combined share of enrollment has dropped from 45 percent in 2006 to 39 percent in 2015. UnitedHealth, due in part to its successful marketing relationship with AARP, has maintained its top position for all ten years of the program and has seen its enrollment grow by about 46 percent since 2006. Humana has maintained a strong Part D presence, due in part to offering the lowest PDP premiums in 2006 and retaining many of those enrollees over time despite premium increases for its older plans. While higher-than-average premium increases and a loss of LIS benchmark status in most regions contributed to a drop in Humana’s Part D enrollment between 2006 and 2010, Humana’s introduction of new lower-premium PDPs in 2011 and 2014 reversed this decline, contributing to a net enrollment gain of 62 percent in Humana’s Part D plans between 2006 and 2015.

Market Concentration

At the national level, the Part D market among PDPs is not concentrated. As measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman index, a statistical measure of market competition, the index value of 1,362 falls a little below the threshold for a concentrated market.8

Within regions, however, the Part D (at the firm level), is moderately concentrated with an average index value across regions of 1,896. Overall, 30 of 34 regions qualify as moderately concentrated, while 2 are highly concentrated and 2 are not concentrated. The two regions classified as highly concentrated are Florida and Nevada.

If non-LIS and LIS beneficiaries are treated as separate markets in each region, both are more concentrated at the firm level than at the level of overall enrollment. In 2015, the LIS population reaches the level considered moderately concentrated in 25 of 34 regions and highly concentrated in another 3 regions. Comparable numbers for the non-LIS population are 20 moderately concentrated regions and 14 highly concentrated regions. The non-LIS market is considerably more concentrated than the LIS market, probably because the process for assigning LIS beneficiaries to benchmark plans reduces concentration. The most concentrated regions among non-LIS beneficiaries are Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, New Jersey, and New York.

Proposed plan acquisitions of Humana by Aetna and Cigna by Anthem would increase market share among two of the top ten Part D plan sponsors. Should the proposed acquisition of Humana by Aetna be approved by federal regulators, the combined firm will increase its market share from 18 percent to 24 percent and surpass UnitedHealth to become the largest sponsor of Part D plans (both for PDPs and MA-PD plans). The share of enrollment for the top three firms would increase from 50 percent to 56 percent. The share of the top three firms for PDP enrollment would increase from 58 percent to 64 percent.

By contrast, the MA-PD plan market is less concentrated at the national level, but much more concentrated at the local level.9 Only three firms in the MA-PD market, accounting for about half of MA-PD plan enrollment (excluding special needs plans), offer plans in at least half the states. The vast majority of MA-PD plan sponsors are local or regional, offering plans in just one or two states. These firms collectively account for about 30 percent of MA-PD enrollment.

Market Share Among Part D Plans

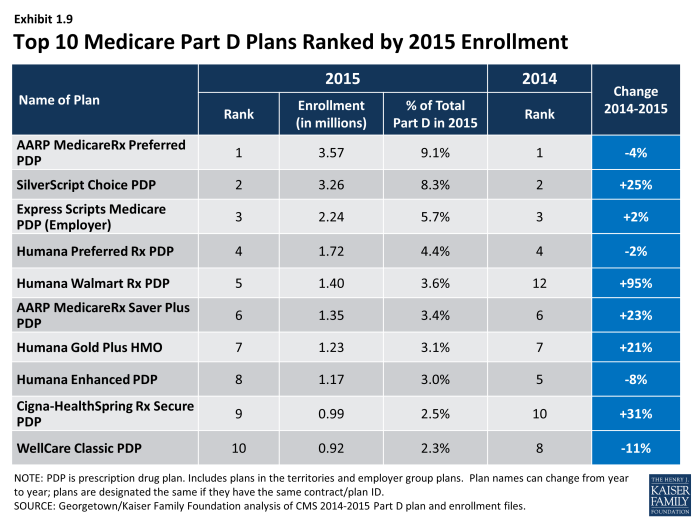

There has been some turnover among the top Part D plans from 2014 to 2015, with one plan moving into the top ten PDPs or MA-PD plans by enrollment (Exhibit 1.9). Humana’s Walmart Rx PDP, new in 2014, moved up to the fifth position, while Kaiser Permanente’s Senior Advantage dropped from the ninth to the eleventh spot. In addition to Humana Walmart Rx PDP, four other top plans gained significant numbers 0f enrollees from 2014 to 2015: Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure PDP, SilverScript Choice PDP, AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP, and Humana Gold Plus HMO. The first two of these gained enrollees through consolidations of other plans offered in 2014 by the same sponsor. Three of the top plans in 2015 (Humana’s Preferred Rx PDP and Walmart Rx PDP and UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP) are recent entries to the market, featuring low initial premiums and tiered pharmacy networks.

Only three of the top ten PDPs or MA-PDs by enrollment in 2015 were among the top ten in 2006. They are UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP, Humana’s Enhanced PDP, and CVS Health’s SilverScript Choice PDP (renamed from SilverScript Basic in 2015) (Exhibit 1.9). Within many plan sponsors’ offerings, there have been significant changes in enrollment, partly due to sponsors adding, dropping, or consolidating plans. Six of the original top ten plans from 2006 exited the market due to consolidations by plan sponsors, some after being acquired by another sponsor.

Enrollment gains at the plan level between 2014 and 2015 were experienced by both plans raising premiums and plans with significant premium reductions. Two PDPs gaining large numbers of enrollees (Humana Walmart Rx PDP and UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP) raised premiums by more than 20 percent, but still had relatively low premiums compared to the competition. In particular, the Humana Walmart Rx PDP, which was introduced in 2014 and had the lowest premium in most regions in 2015 despite a premium increase, nearly doubled its enrollment (95 percent) between April 2014 and April 2015 and became the fourth largest PDP in 2015. By contrast, Humana’s more expensive plan (Humana Enhanced PDP) experienced a 8 percent loss in enrollment between 2014 and 2015, Over the program’s first decade, Humana has refreshed its offerings by introducing new low-premium plans while raising premiums for its older plans. Two other PDPs with large enrollment gains from 2014 to 2015 had significant premium reductions (SilverScript Choice PDP and Cigna-HealthSpring Rx Secure-Xtra PDP). It is unclear whether the gains were beneficiaries new to Medicare, transfers from other PDPs offered by the same sponsor, or switchers from plans offered by other sponsors.

Low premiums were associated with enrollment growth at times other than the annual open enrollment period. Humana has been most successful in this regard, benefiting from its strategy of offering PDPs with low premiums to capture a large share of the market. The firm’s Walmart Rx PDP enrolled 229,000 new members outside the annual enrollment period (February to December 2014) for a 35 percent increase in enrollment and another 164,000 new members (12 percent increase) between February and September 2015. Because most enrollees have no option to switch plans in these months, it is likely that most of these new enrollees are newly eligible Medicare beneficiaries opting for the least expensive plan. UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP and the WellCare Classic PDP, also offering some of the lowest PDP premiums during 2014, picked up substantial numbers of enrollees during 2014 and the UnitedHealth plan had further gains during 2015.

Enrollment shifts among the top plans and plan sponsors also have been brought about by automatic re-assignment of LIS beneficiaries. If a plan loses its designation as a benchmark plan (available to LIS beneficiaries for zero premium), CMS reassigns certain beneficiaries to a benchmark plan offered by the same sponsor if one is available; otherwise they are switched at random to a benchmark plan offered by another sponsor. In 2015, for example, Aetna and CVS Health each picked up nearly 90,000 enrollees through these types of reassignments. By contrast, three PDPs not designated as benchmark plans experienced disenrollment of LIS enrollees and thus had among the largest decreases in total enrollment from 2014 to 2015.

The most popular plans vary considerably by region. UnitedHealth and CVS Health each have the largest PDPs in nearly half of all regions in 2015.10 UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP is the largest PDP in 16 regions, and CVS Health’s SilverScript Choice PDP is the largest in 14 regions. Humana Preferred Rx PDP holds the lead in Colorado and Nevada. Humana Walmart Rx PDP and Cigna-HealthSpring Secure PDP have the largest shares of enrollment in the Idaho/Utah region and Hawaii, respectively.

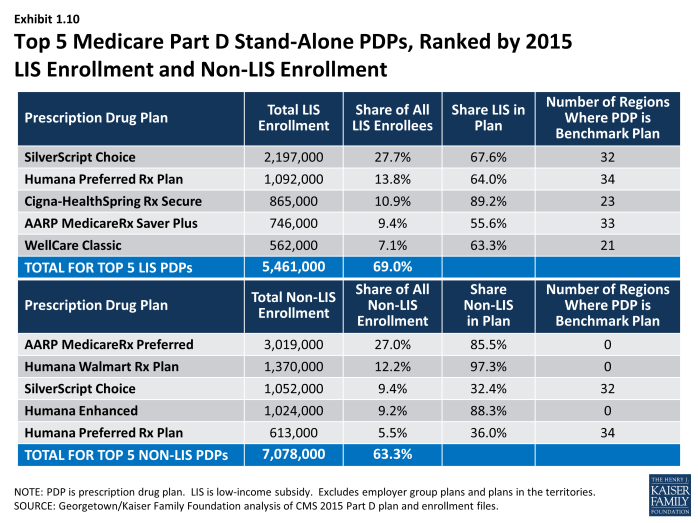

The most popular plans also differ for non-LIS and LIS beneficiaries. AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP has enrolled 27 percent of all non-LIS beneficiaries nationally and has the most non-LIS enrollees in 29 of 34 PDP regions (Exhibit 1.10). The next most popular non-LIS plan, Humana’s Walmart Rx PDP, with 12 percent of non-LIS enrollees, has the most non-LIS enrollees in three regions, and local Blue Cross Blue Shield PDPs have the largest share of non-LIS enrollment in Arkansas and the upper Midwest region.

CVS Health’s SilverScript Choice PDP dominates the LIS market with more than one-fourth of national LIS enrollment (28 percent) and the highest share of LIS enrollees in 25 PDP regions. PDPs sponsored by Humana, Cigna, and WellCare have the most LIS enrollees in the other 9 PDP regions. Unlike the situation in recent years, four of the five PDPs with the most LIS enrollees have an enrollee mix with at least one-third non-LIS enrollees.

Plan Availability

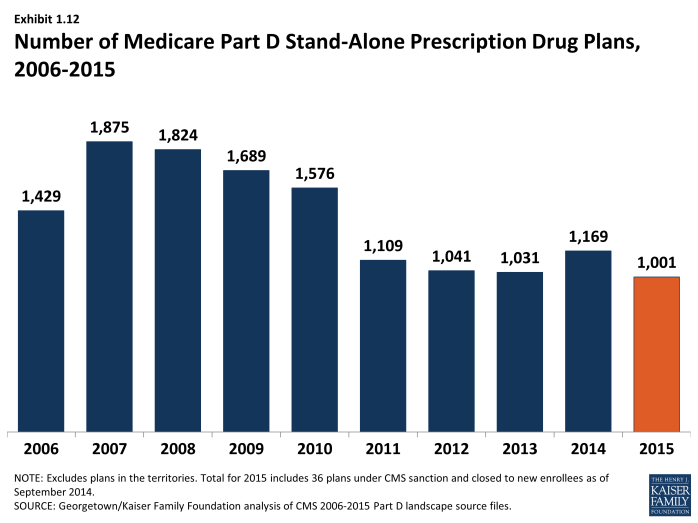

Choice remains plentiful in Part D; in 2015, the average Part D enrollee had a choice of 30 PDPs and 15 MA-PD plans. The average number of PDPs per region has come down from a high of 56 in 2007 and 35 in 2014 to 30 in 2015 (weighted by regional enrollment) (Exhibit 1.11). At least 24 PDPs are offered in every region this year (excluding the territories). In 2015, virtually all beneficiaries have at least one Medicare Advantage option with drug coverage as well, and the average beneficiary has 15 options for Medicare Advantage drug plan enrollment, down from 26 in 2009 and up from 14 in 2014.11

The number of PDPs offered was down by 14 percent from 2014 to 2015. There are 1,001 PDPs in 2015, well below the number of PDPs offered between 2006 and 2010. While the number of PDPs rose sharply between 2006 and 2007, the number decreased each year since (other than 2014) as a result of both marketplace and policy factors (Exhibit 1.12). Over its first ten years, the Part D market has witnessed several mergers between sponsoring organizations and consolidation of plan offerings by sponsors. In 2010, CMS issued regulations aimed at discouraging duplicative plan offerings and plans with low enrollment. For example, many sponsors now offer just two plan options (one basic and one enhanced) instead of the three options they had offered in previous years.

The drop in PDP offerings from 2014 to 2015 reflects plan terminations and a few offsetting new offerings. The only near-national plan sponsor leaving Part D, HealthMarkets, had never attracted significant enrollment in its two years. Three plan sponsors with a small regional presence also terminated contracts. In addition, Anthem terminated its MedicareRx Rewards PDPs in 24 regions. These PDPs entered the program in 2006, but enrollment had fallen steadily in recent years. The largest number of terminations (168 PDPs) reflected plan consolidations by five national plan sponsors and two local plan sponsors. Some consolidations resulted from earlier mergers among sponsors, and others were in response to CMS guidance on duplicative plan offerings. Partially offsetting the plan terminations were 70 new plans, nearly all from three national or near-national plan sponsors (EnvisionRx, Symphonix Health, and United American) with relatively few enrollees. There are two entirely new contracts offering one PDP in Colorado and two in Nevada. Together all the new plans attracted only 170,000 enrollees (about 1,000 enrollees for the new contracts). Over half (93,000) were in one new plan (sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield in the upper Midwest region); the rest averaged just over 1,000 enrollees per plan. Some enrollees in new PDPs appear to have shifted from others offered by the same sponsor.

Current CMS policies suggest that the number of PDPs might decline again in future years. In the call letter issued in early 2015 spelling out the terms of plan participation for the 2016 contract year, CMS reiterated the agency’s authority not to renew plans with low enrollment.12 Currently, 257 PDPs (26 percent of all PDPs in 2015) have fewer than 1,000 enrollees, the level at which CMS urges sponsors to consider plan withdrawal or consolidation; 63 of these PDPs have fewer than 100 enrollees each.13 The low-enrollment PDPs include the Symphonix Premier Rx and Symphonix Rite Aid Premier Rx PDPs in 25 regions, which were offered for the first time in 2014.

In addition to its policy on low-enrollment plans, CMS continues to maintain a policy that PDPs offered by the same sponsor must be meaningfully different from the sponsor’s other offerings. This policy encourages plan sponsors to reduce their PDP offerings, thereby simplifying the choice environment in Part D.

In 2015, 1,605 Medicare Advantage drug plans are offered, essentially the same number as the year before. The number of MA-PD plans increased by about 50 percent between 2006 and 2009, from 1,333 plans to 1,991 plans.14 However, the availability of MA-PD plans has fallen since then; the 1,605 MA-PD plans offered in 2014 is about 19 percent lower than at the peak. The number of MA-PD plans available to the average Medicare Part D enrollee has remained nearly constant at 15 plans since 2011.

Section 1: Part D Enrollment and Plan Availability

exhibits

Section 2: Part D Premiums

National Premium Trends

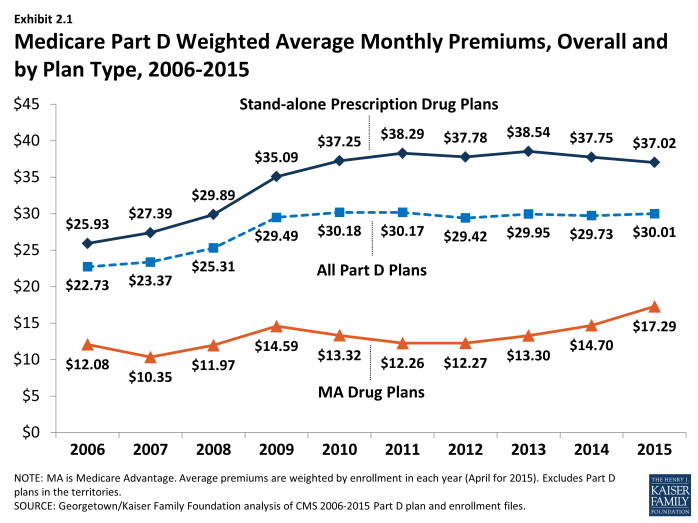

Since 2006, the average PDP premium, weighted by enrollment, has increased by 43 percent, but the 2015 average is 2 percent lower than in 2014 and 4 percent lower than at the peak in 2013. The weighted average monthly premium paid by beneficiaries for stand-alone Part D coverage has increased since the start of the program, from $25.93 in 2006 to $37.02 in 2015 (Exhibit 2.1).1,2 Premiums have been essentially flat since 2010, down slightly from 2010 to 2015. A key factor driving slow premium growth in recent years is the availability of generic versions of many drugs used for common chronic conditions, which helps to limit growth in total plan costs and hence premiums.3

The average monthly Part D premium, including both PDPs and MA-PDs, has increased from around $23 per month in 2006 to $30 per month in 2015, but has been essentially flat since 2010 (Exhibit 2.1).

Average monthly MA-PD plan premium are lower than average premiums for PDPs, but have been increasing since 2011 (compared to the flat premium trend for PDPs). The average 2015 monthly premium amount attributable to drug benefits in MA-PD plans is $17.29, up 18 percent from $14.70 in 2014 and up 30 percent from $13.30 in 2013. MA-PD premiums on average are higher in 2015 than in any year since the program began.4

At the same time, the MA-PD average monthly premium is about $20 below the PDP average monthly premium, because many MA-PD plans use a portion of rebates from the Medicare Advantage payment system to reduce or eliminate their premiums. In 2015, CMS calculated that the average MA-PD premium prior to rebates was about $3 per month lower than those for PDPs (a smaller differential than in previous years); thus, the average plan applied a rebate amount of about $17 to lower the premium in 2015.5 The increase in the MA-PD premium from 2013 to 2015 may reflect changes in the Medicare Advantage payment rules, which may have lowered these rebates. Nearly half (42 percent) of all MA-PD plans, with 52 percent of MA-PD enrollees, charge no premium for their drug benefit.

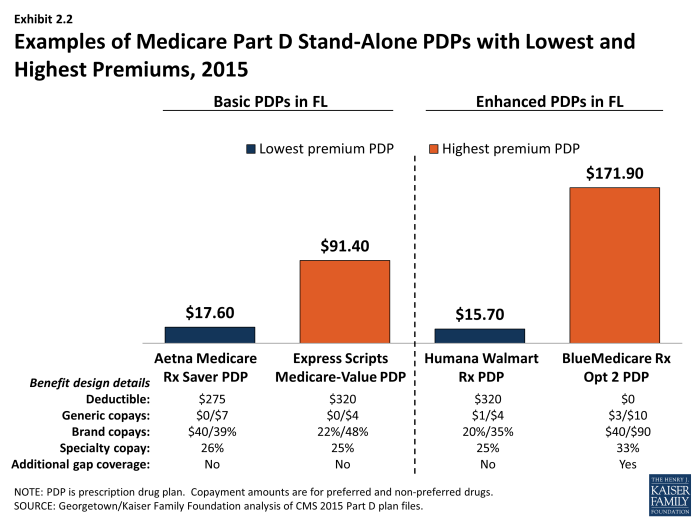

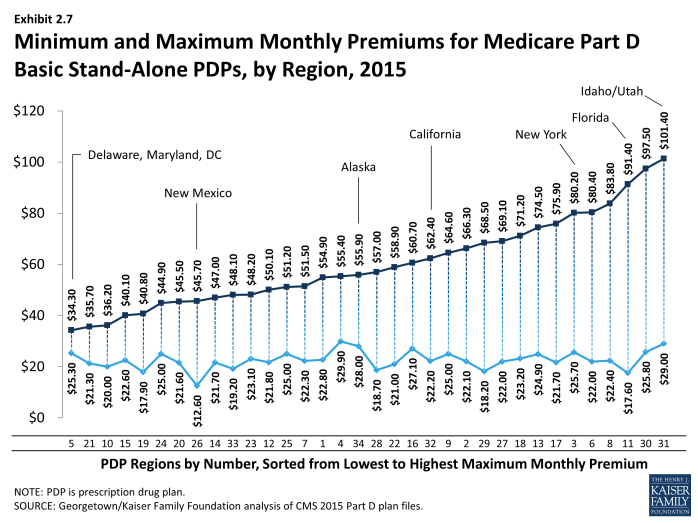

PDP premiums vary widely. Nationwide, the least expensive PDP has a $12.60 monthly premium, while the most expensive PDP has a $171.90 premium, a 14-fold difference. Although the difference can be explained partly by the relative generosity of the benefits offered or the relative efficiency across plans, these factors seem unlikely to explain the full difference. Even among plans with equivalent benefits (those offering the basic Part D benefit), premiums vary from $12.60 to $101.40 per month. As illustrated in the lowest and highest-premium PDPs in the Florida region, benefit differences are modest relative to the large premium differences (Exhibit 2.2). Although enrollees in the highest-premium enhanced plan have some coverage in the gap and no deductible and flat cost sharing for brand drugs, they face higher cost sharing for generic and specialty drugs than the lowest-premium enhanced PDP in Florida. Those enrolled in the highest-premium basic PDP have a higher deductible than those in the lowest-premium basic PDP and are subject to coinsurance for brand drugs.

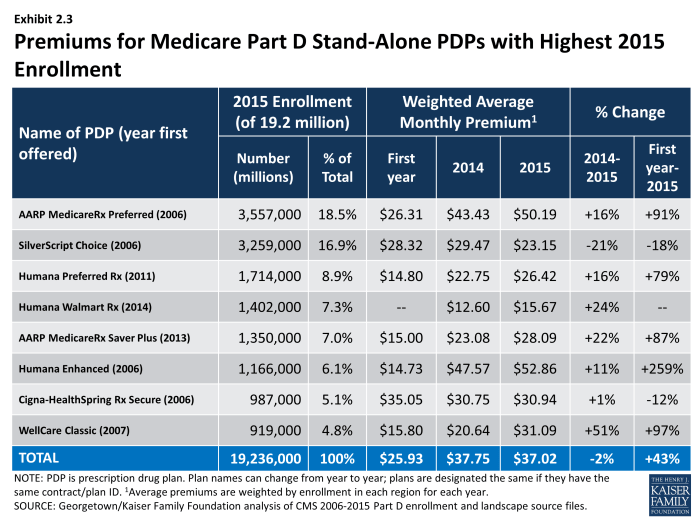

Plan-Level Premium Trends

Seven of the eight PDPs with the highest enrollment charged higher average premiums in 2015 compared to 2014, whereas one lowered its average premium. More generally, the modest decrease in the average premium for all Part D enrollees hides larger changes at the plan level (Exhibit 2.3). For example, the plan with the highest enrollment, UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP, increased the monthly premium by 16 percent compared to 2014 (from $43.43 to $50.19). All three plans sponsored by Humana raised premiums by 11 percent or more. By contrast, the Silverscript Choice PDP, offered by CVS Health, lowered its average premium by 21 percent (from $29.47 to $23.13).

Some older, established plans have raised premiums more rapidly than the national average, while newer plans tend to set premiums low in order to build enrollment but may raise them rapidly in subsequent years. As a result, beneficiaries who stay in the same plan tend to pay more over time, as earlier research finds relatively few enrollees switch plans voluntarily in a given year.6 Established plans tend to retain enrollees as they age, when they typically use more drugs, whereas newer plans attract younger enrollees who are likely to have lower drug use and also more likely to shop based on premiums when they first enter the market. Premiums for some new plans have increased rapidly within a year or two of entering the market. For some plan sponsors, this strategy may be a conscious attempt to attract younger enrollees in newer, less expensive plans while still retaining their existing enrollees in older, more expensive plans.

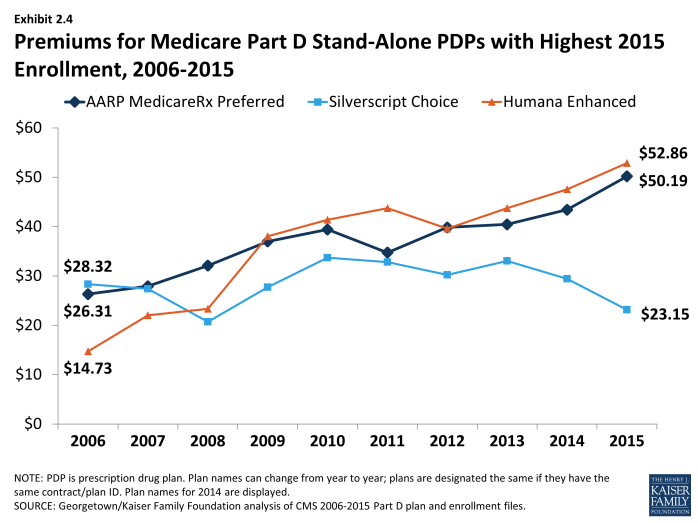

Most plans that have been in the program since 2006 have increased premiums by more than the national average. Overall, of 315 PDPs that have operated under the same contract and plan numbers from 2006 to 2015 (despite some corporate acquisitions and name changes), about 40 percent have monthly premiums in 2015 that are at least double the premium in 2006, and two-thirds have raised premiums over this period by more than the national average increase. For example, the average monthly premium for Humana’s Enhanced PDP in 2015 is more than 3.5 times its 2006 average ($52.86 versus $14.73) (Exhibit 2.4). Over the same period, the premium for UnitedHealth’s AARP Medicare Rx Preferred PDP nearly doubled ($50.19 versus $26.31). By contrast, one-fourth of these continuously operating PDPs have a lower premium in 2015 than in 2006. Silverscript Choice PDP had a 18-percent lower premium in 2015 compared to 2006 ($23.15 versus $28.32).

Some of the program’s newer plans have experienced large percentage premium increases. The average premium for Humana’s Preferred Rx PDP is higher by 79 percent ($14.80 to $26.42) in four years after entering the program. UnitedHealth’s AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP has experienced a net 87-percent premium increase ($15.00 to $28.09) in three years.

Overall, enrollment increased (by 13 percent) in plans that lowered premiums, while enrollment was generally flat (down by 1 percent) in plans that raised premiums. PDPs that lowered premiums by at least 20 percent had an average enrollment gain of 34 percent. By contrast, PDPs that raised premiums by at least 30 percent experienced a 15 percent average drop in enrollment. Patterns were not consistent, however, as PDPs that raised premiums 20 percent to 30 percent gained enrollment, and those that lowered premiums up to 10 percent lost enrollment. Some of the enrollment gain came from random assignment of LIS enrollees, but enrollment by non-LIS beneficiaries was considerably higher as well. Our analysis of plan switching from 2006 to 2010 found that 87 percent of beneficiaries in any particular annual enrollment period did not change plans.7 But generally consistent with patterns in 2015, those whose premiums were increasing by $10 or more were more likely to change to plans with lower premiums; 21 percent of those with a $10 to $20 premium increase and 28 percent of those with a premium increase of $20 or more changed plans.

As with PDPs, average premiums vary considerably by MA-PD plan sponsor. Plans offered by UnitedHealth, with 20 percent of the MA-PD market, have a weighted average premium of $11.44 for the drug benefit (in addition to a Part C premium of $5.02 that covers the medical benefits normally provided by traditional Medicare). The other leader in this market segment is Humana, also with 20 percent of MA-PD enrollees, which has a modestly higher average premium of $14.37 (plus $17.94 for Part C). The next two largest MA-PD sponsors are Kaiser Permanente, with a 9 percent market share and a $4.79 average premium (plus $35.85 for Part C), and Aetna, with a 6 percent market share and a $7.13 average premium (plus $16.62 for Part C).8

Geographic Variations in Premiums

Average premiums are considerably higher in certain regions than in others in 2015. Beneficiaries enrolled in a basic PDP pay an average of $36.89 in the Idaho/Utah, more than double the average ($16.97) in New Mexico (Exhibit 2.6).9 Regional differences in premiums have generally persisted from year to year and continued to grow wider in 2015. New Mexico and Arizona have been among the regions with the lowest average premiums since the program began, while the Idaho/Utah region has been among the most expensive regions.

At the same time, some regions have seen significant changes in their average PDP premiums relative to other regions. The average PDP premium in New York, for example, was below the national average from 2006 to 2010, and then increased to be above average each year since then. Regional differences in the average PDP premium were smaller in the program’s first two years, before plan sponsors could look at actual claims experience for guidance in setting premium levels.

Although persistent regional differences in premiums are driven in part by underlying regional differences in drug utilization, further explanations are not readily apparent. Plan risk scores, averaged by region for 2013 (the most recent year available) are correlated modestly (r=0.24) with that year’s average premium for basic PDPs, providing some support for the notion that utilization is a factor. In 2013, there was also a modest correlation (r=0.33) between the number of basic PDPs in each region with the average premium for those PDPs, counter to the notion that more competing plans leads to lower plan bids. In 2015, however, number of plans was not correlated with premiums, but was modestly correlated (r=-0.25) with a measure of concentration; regions that were more concentrated had lower premiums—again running counter to expectations. More research is needed to understand the patterns of geographic variation in Part D premiums.

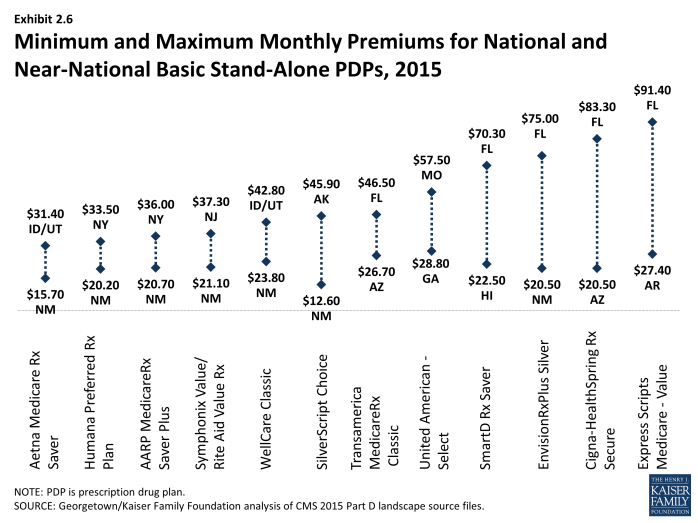

Geographic differences in premiums are greater for some plan sponsors than others; some sponsors charge as much as three times more for the identical basic PDP from one region to another. Twelve plan sponsors offer a basic PDP in at least 30 of the 34 PDP regions. For seven of these national or near-national PDPs, premiums for the identical plan design are at least two times greater in one region than in another (Exhibit 2.6). The largest absolute premium difference is for the Cigna-HealthSpring PDP, which charges beneficiaries $20.50 in Arizona and $83.30 in Florida for the same coverage—a difference of $62.80 (a wider difference than in 2014). By contrast, the Humana Preferred Rx PDP has a difference of only $13.30 between its lowest and highest regions ($20.20 in New Mexico and $33.50 in New York), but that difference is also wider than in 2014. For six of these national or near-national PDPs, the highest premiums are in states (Florida, Missouri) where premiums overall are below the national average.

Within each region, some plan sponsors charge several times more than competing sponsors for their basic PDPs (Exhibit 2.7). In the region that includes Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, DC, the highest premium for a basic PDP is $34.30 for United American’s Select PDP, which is only one-third higher than the $25.30 premium for Aetna’s Medicare Rx Saver PDP. This region had the largest range of premiums in 2014, but several of the high-premium plans exited the market including the BlueRx Standard PDP with a 2014 premium of $111.40. The largest premium range among basic PDPs is in Florida, where the Express Scripts Medicare-Value PDP charges $91.40, seven times the lowest premium in its region ($17.60 for Aetna Medicare Rx Saver PDP). By law, all basic PDPs provide a benefit with the same actuarial value. Different utilization patterns by plan enrollees (adverse selection, beyond what can be compensated for by the risk-adjustment system used by CMS) may be a key factor driving the larger premium differences.

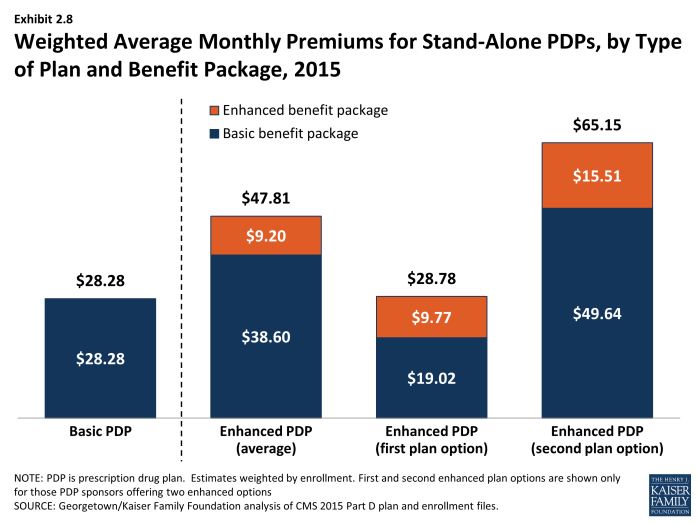

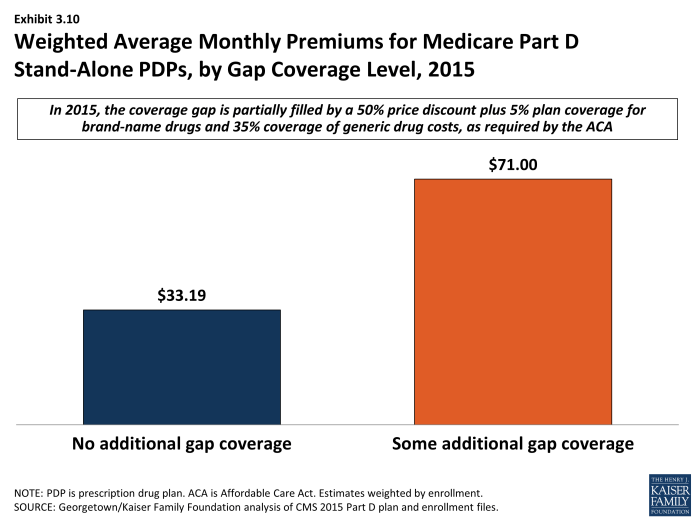

Premium Variations by Plan Type

Beneficiaries selecting PDPs with an enhanced benefit package pay higher premiums on average for their Part D coverage, even for the part attributable to the basic benefit package. The weighted average monthly premium for PDPs with enhanced benefits is $47.81, compared to $28.28 for PDPs offering the basic benefit package (Exhibit 2.8). Thus, enrollees pay nearly 70 percent more to get enhanced benefits.

Plan sponsors mostly add value in their enhanced plans by lowering deductibles and sometimes adding coverage in the gap. Most enhanced plans lower or eliminate plan deductibles; 71 percent of enhanced PDPs have no deductible, compared to 7 percent of basic PDPs (the share of enhanced PDPs without a deductible is down from 89 percent in 2014). If eliminating the deductible were the only difference, beneficiaries would be paying an additional premium of $19.53 per month ($47.81 versus $28.28) or $234 annually to eliminate a $320 deductible. Some enhanced plans also expand the coverage of drugs during the coverage gap beyond the amount included in the basic benefit (48 percent of enhanced PDPs). Plans also may use lower cost sharing as part of an enhanced benefit, but as shown in the section below on cost sharing, enhanced PDPs on average charged higher cost sharing in 2015.

Starting with PDPs offered in 2011, CMS has required sponsors to ensure that benefits in enhanced PDPs are meaningfully different than the basic benefits and have a measurable added value. This policy has led to a larger spread between premiums for basic PDPs and enhanced PDPs than in previous years. In 2015, an enhanced PDP must have cost-sharing differences that result in at least $20 lower monthly out-of-pocket costs than the corresponding basic PDP—an amount that is essentially offset by the $19.53 average monthly premium difference between basic plans and enhanced PDPs.

Some PDP sponsors offer two enhanced plans, a less generous first option and a more generous second option; average monthly premiums for the more generous enhanced PDPs offered by these sponsors are much higher than the first option’s premium ($65.15 versus $28.78). As part of its policy on meaningful differences, CMS allows sponsors to offer a second enhanced PDP only if expected out-of-pocket cost sharing amounts are lower (by $25 per month) than for the first enhanced PDP and the second enhanced PDP has coverage for at least some brand-name drugs in the coverage gap. The $36 difference in premiums exceeds the required difference in out-of-pocket costs.

Although higher premiums partly reflect the cost of offering enhanced benefits, the portion of the premium that corresponds to the basic benefit ($38.60 on average for enhanced PDPs) is higher than the premium for basic PDPs ($28.28) (Exhibit 2.8). For some sponsors, the difference is much greater. Risk selection may be a factor in these higher premiums, although in 2013 enrollees in enhanced PDPs actually had lower risk scores (0.94) than those in basic PDPs (1.05), mostly attributable to enrollees in the less generous enhanced PDPs. But it may be that the enhanced plans have attracted beneficiaries with higher drug needs beyond differences captured by risk adjustment. Furthermore, even though program rules seem to disallow it, plan sponsors may cross-subsidize some of the supplemental portion of bids for enhanced plans with the basic component in order to maximize the government subsidy.10

Some plan sponsors offer enhanced PDPs that have the minimum level of enhanced coverage required by the meaningful difference tests and are offered at low premiums with the apparent goal of attracting beneficiaries with low expected drug costs. In 2015, for example, one of Humana’s enhanced PDPs (Walmart Rx) is offered at an average premium of $15.67 per month, whereas its basic PDP (Preferred Rx) is $26.42. For several other plan sponsors, the portion of the premium attributable to a plan’s basic benefits (thus excluding the value of any enhanced benefit) is lower for their enhanced PDPs compared to their basic PDPs. A key reason for lower premiums in these enhanced plans is favorable risk selection that occurs because they are attractive to non-LIS beneficiaries who are using few drugs and because there are relatively few LIS beneficiaries enrolled in enhanced plans. In 2013, the average risk score for enrollees in the less generous enhanced PDPs was 0.93, compared to 1.04 in the more generous enhanced PDPs.

Section 2: Part D Premiums

exhibits

Section 3: Part D Benefit Design and Cost Sharing

Plan Benefit Design

Most Part D plans do not offer the defined standard benefit (with a $320 deductible in 2015 and 25 percent coinsurance); all PDPs and most MA-PD plans have a tiered cost-sharing structure with incentives for enrollees to use less expensive generic and preferred brand-name drugs. For the first time in 2015, no PDPs offer the defined standard benefit without formulary tiers. Among MA-PD plans, 2 percent offer the defined standard benefit with 1 percent of enrollment.1

A majority of Part D enrollees are in enhanced plans. In 2015, 53 percent of all Part D enrollees are in enhanced plans, designed to offer some benefits beyond the basic benefits defined in law. Nearly half (45 percent) of PDP enrollees and 72 percent of MA-PD enrollees are in enhanced plans.

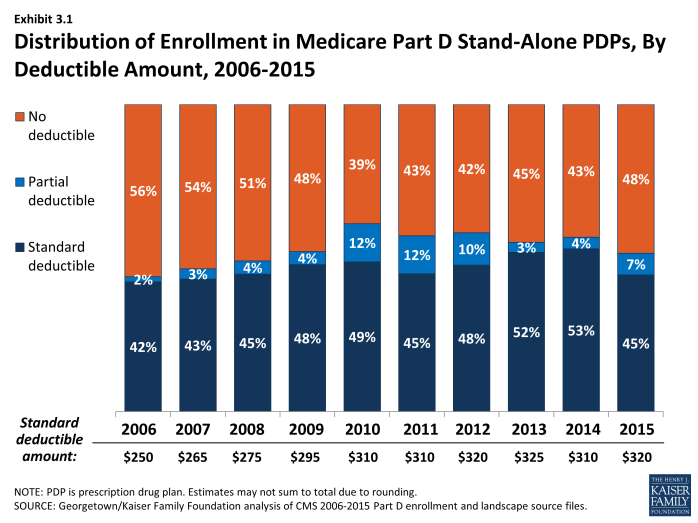

Use of a deductible by stand-alone PDPs is considerably higher in 2015 than in the first few years of the program. About 58 percent of PDPs charge a deductible this year, compared to a high of 60 percent in 2010. Most PDPs with a deductible use the standard deductible allowed by law ($320 in 2015). Nearly half of PDP enrollees are in plans with no deductible (48 percent of enrollees), compared to 56 percent of PDP enrollees in 2006 (Exhibit 3.1). A smaller number of MA-PD plans (37 percent) than PDPs have a deductible in 2015, but use of a deductible is up substantially from 2014 (14 percent). More than half of the MA-PD plans with a deductible set the level lower than the maximum of $320. Overall, 51 percent of all Part D enrollees are enrolled in plans with no deductible, and 33 percent are in plans with the maximum deductible. In contrast to Part D, only a small share of workers with employer sponsored drug coverage (12 percent) face a separate drug deductible, averaging $231 in 2015.2

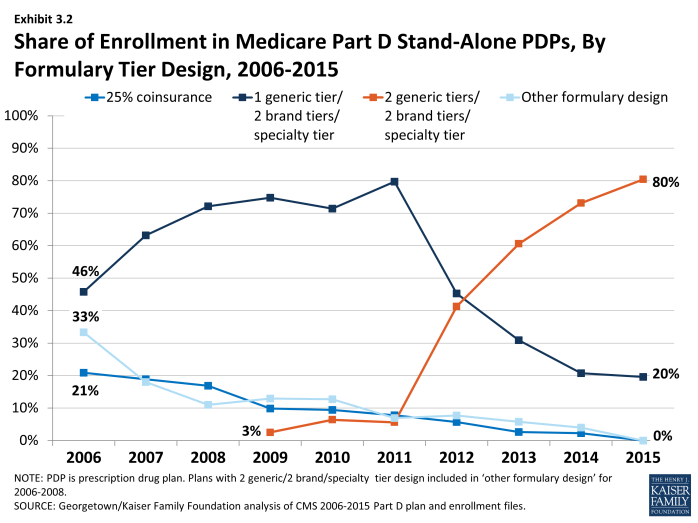

In 2015, the vast majority of all Part D enrollees (80 percent of PDP enrollees and 91 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees) are in plans that use five cost-sharing tiers: preferred and non-preferred tiers for generic drugs, preferred and non-preferred tiers for brand drugs, and a tier for high-cost specialty drugs (see section below, ‘Specialty Tiers’) (Exhibit 3.2). Overall, 84 percent of the combined enrollment in PDPs and MA-PDs are in plans with five tiers. In 2015, 90 percent of PDPs and 87 percent of MA-PD plans used five-tier designs. Most of the other Part D enrollees are in plans with four tiers: one generic tier, two brand tiers, and a specialty tier.3 By contrast, enrollees in 2006 were in PDPs with a greater variety of tier structures, including significant numbers in plans with three-tier and four-tier arrangements. Four-tier arrangements were most common until 2012 when plans began shifting toward the five-tier cost-sharing design.

Part D plans use more cost-sharing tiers than private-sector employer plans. Whereas all PDP enrollees and nearly all MA-PD enrollees are in plans with four or more tiers, only 23 percent of covered workers in employer-sponsored plans are in plans with that many tiers, while 13 percent are in plans with two tiers or no tiered cost sharing.4 The trend among employer plans has been to use more tiers, and some have gone to five tiers, but this design is used much less often than in Part D.

Part D Cost-Sharing Amounts

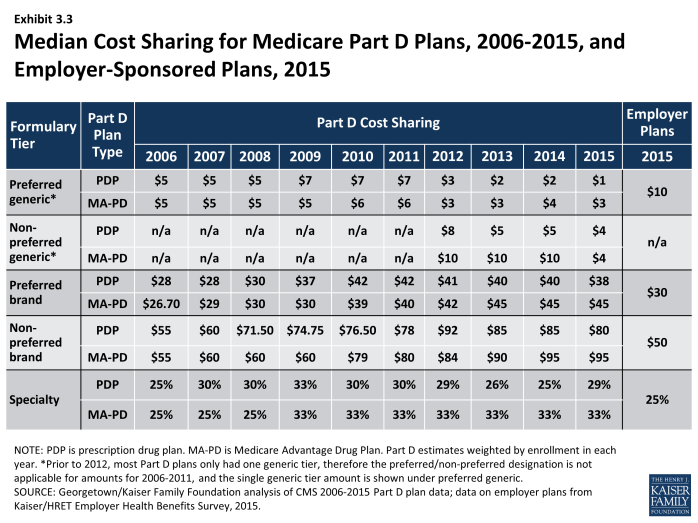

While cost sharing has been relatively stable in recent years, the median cost sharing for a 30-day supply of non-preferred brand-name drugs in stand-alone PDPs has increased by 45 percent since 2006, from $55 to $80, while cost sharing for preferred brand drugs increased by 36 percent, from $28 to $38 (Exhibit 3.3). Median cost sharing in PDPs for both brand tiers was modestly lower in 2015 compared to 2014. Cost-sharing amounts for brand-name drugs vary widely across Part D plans in 2015, as they have in previous years. For preferred brand tiers, PDPs charge copayments as low as $19 and as high as $45. About 80 percent of spending on brand drugs for Part D enrollees was for drugs on preferred brand tiers,5 so these are the cost-sharing levels encountered most often. For non-preferred brand tiers, copayments range from $35 to $95. These ranges are less than in some previous years because of CMS guidance that sets maximum allowable copayment levels.

Median cost sharing for preferred generic drugs in PDPs (or for generic drugs among plans with a single generic tier) is $1 in 2015, lower than in any year since the program began. As a result of lower generic copays, the spread between brand and generic tiers widened modestly from 2011 to 2015. For PDPs with two generic tiers (most PDPs and PDP enrollment), the median cost sharing is $1 for the preferred generic tier and $4 for the non-preferred tier. These copay amounts are lower than in any previous year; in fact, the copay for non-preferred generics is lower than the copay for the single generic tier as recently as 2011. By contrast, however, one PDP charges a $28 copayment for its non-preferred generic tier in 2015, well above any other PDP.

Despite the trend to higher cost sharing, beneficiaries’ average total out-of-pocket costs have not increased. According to MedPAC, for the average Part D enrollee not receiving the LIS, monthly out-of-pocket spending declined from $59 to $47 from 2007 to 2012 (the most recent year available).6 The impact of partially closing the coverage gap and more use of generic drugs has generally balanced the impact of higher cost sharing for brands.

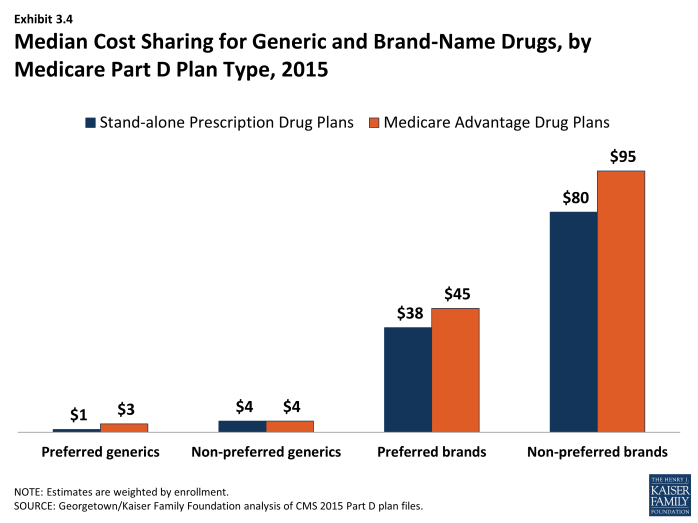

In 2015, median cost-sharing amounts are generally higher in MA-PD plans than in PDPs in all tiers. For example, the median cost sharing for preferred brands in MA-PD plans is $7 more than the median in PDPs ($45 versus $38) and $2 more for preferred generic drugs ($3 versus $1) (Exhibit 3.4). The comparisons for UnitedHealth, the sponsor with largest share of both PDP and MA-PD enrollment, illustrate the pattern. For preferred and non-preferred generic drugs, UnitedHealth’s median cost sharing, weighted by enrollment, is $2 and $5 in its PDPs and $2 and $8 in its MA-PD plans, respectively. The differences for brand drugs for UnitedHealth’s plans mirror the national differences. It is unclear why cost sharing is higher for MA-PD plans, especially since more of them offer enhanced benefits. Further work is needed to assess variations in copayments by Part D plan type, including for example, the extent to which these differences persist across all plan sponsors and within different geographic areas. Another question is whether there are differences in tier placement of specific drugs and whether some plans cover more drugs than others on specific tiers that may be factors in explaining differences in cost-sharing amounts between types of Part D plans.

Combined across PDPs and MA-PD plans in 2015, median cost-sharing amounts for generic drugs (weighted by enrollment) are $2 for preferred generics and $6 for non-preferred generics. For brand drugs, median copayments are $40 and $90 for preferred and non-preferred brands.

Copayments in the form of a flat dollar payment amount remain the most common type of cost sharing; however, the share of PDPs using percentage-based coinsurance for non-specialty brand-name drug tiers has increased since 2006. In 2015, 68 percent of PDPs with a tier for non-preferred brand drugs charge a coinsurance rate for drugs on that tier, a large jump from 37 percent in 2014. Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of PDP enrollees are in plans with coinsurance for this tier. Of these plans, nearly all have a mixed pricing design. Typically they use a flat copayment for their generic drug tiers, and many also use a flat copayment for preferred brand drugs; 27 percent of PDPs (28 percent of enrollees) use coinsurance for preferred brand tiers, about the same as in 2014. The use of percentage coinsurance for drugs remains uncommon among MA-PD plans (13 percent for the non-preferred brand tier). In 2006, only a small share of PDPs with tiered cost sharing used coinsurance for their brand tiers (12 percent of enrollees for preferred brands and 14 percent of enrollees for non-preferred brands), but in addition nearly one-fourth of PDP enrollees were in standard plans with 25-percent coinsurance. Overall, 43 percent and 18 percent of Part D enrollees have coinsurance for non-preferred brands and preferred brands, respectively.

For plans that use percentage coinsurance instead of dollar copayments, the actual amount an enrollee pays depends on the retail price of the drug. The median coinsurance percentage for PDPs in 2015 for the preferred brand tier is 20 percent. For a brand-name drug with a typical cost of $250, the coinsurance would be $50, more than the median copay amount. For drugs on the non-preferred brand tier, the median coinsurance rate is 40 percent, a substantial share of the drug’s cost and more than the median copay for this tier. In fact, 132 PDPs (up from 29 in 2014) require beneficiaries to pay half the cost of drugs on the non-preferred brand tier, the maximum allowed under CMS guidance.

Cost sharing is generally higher in enhanced PDPs than in basic PDPs. Analysis of enhanced PDPs in earlier years sometimes revealed only small benefit differences compared to the same sponsor’s basic PDPs.7 In 2015, cost sharing in each tier is generally higher for enhanced PDPs than in basic PDPs. For generic drugs, median cost-sharing amounts (weighted by enrollment) are $3 and $5 (preferred and non-preferred tiers) for enrollees in enhanced PDPs, compared to $1 and $4 for those in basic PDPs. For brand drugs, they are $40 and $80 (preferred and non-preferred) versus $35 and $60. Enrollees in enhanced PDPs generally have no deductible, which may constitute the added actuarial value that characterizes enhanced plans. As noted in Section 2, average monthly premiums are about $20 higher for enhanced PDPs, raising questions about the value of these plans for Part D enrollees.

Medicare Part D plans generally charge more than private-sector employer plans do for preferred and non-preferred brand drugs, but less for generics. At the median, PDPs charge $38 per month for a preferred brand in 2015, higher than the median $30 charged by employer plans in 2015, (Exhibit 3.3).8 Cost-sharing differences are even greater for non-preferred brands ($80 for PDPs versus $50 for employer plans). On the other hand, only about one-fourth of workers are in employer plans that use coinsurance for brand tiers. Employer plans charge much higher copays for generic drugs than PDPs charge ($10 versus $1). Thus the spreads between cost sharing for brands and generics and between preferred and non-preferred brand drugs are greater in Medicare Part D plans. Compared to commercial health plans, the typical structure of cost sharing in Part D offers a greater incentive for plan enrollees to choose generics or preferred brand drugs. Furthermore, employer plans are much less likely to use two generic tiers.

Part D enrollees in some plans have the potential for savings if they obtain prescriptions by mail order; in other plans cost sharing is lower at retail pharmacies. Only 40 percent of PDPs (with about half of PDP enrollees) discount the cost sharing for a 90-day supply of a preferred brand drug obtained by mail order versus the same 90-day supply at retail. Among these PDPs, cost sharing is typically about 10 percent lower. About one-tenth of PDP (4 percent of enrollees) actually charge more; in most cases the cost sharing is equivalent to that charged for pharmacies not offering preferred cost sharing (see section on tiered pharmacy networks). Part D allows plans to offer mail order, but requires a level playing field in that at least one retail pharmacy must be able to dispense prescriptions with 90-day supplies. According to a recent study, mail order represented about 8 percent of prescriptions for 300 top drugs dispensed in Part D in 2010 and about 14 percent of spending on those drugs. The study found that Part D plan sponsors do not achieve savings when patients use mail order, because total mail order pharmacies may charge more for drug than retail pharmacies in Part D.9

About one-fifth of Part D PDP enrollees are in plans that offer discounted cost sharing for a 90-day supply at retail pharmacies. In 2015, 11 percent of PDPs with 19 percent of PDP enrollees have discounted cost sharing for a 90-day supply of a drug on a preferred brand tier. Most PDPs offering this discount charge the equivalent of 2.5 monthly copays for a 90-day supply, amounting to about a 17 percent discount. A handful of PDPs charge two monthly copays. All other PDPs have no discount for a 90-day supply.

Specialty Tiers

Nearly all Part D plans use a specialty tier for high-cost medications in 2015. In 2015, all PDP enrollees and 99 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with a specialty tier. Across the two enrollee populations, 99.5 percent are in plans with a specialty tier. Specialty tiers are used by Medicare drug plans for relatively expensive drugs (at least $600 per month in 2015—a threshold that has been unchanged since 2008).

Use of specialty drugs has increased rapidly in recent years (46 percent in 2014 and 15 percent in 2013), driven by growth in the average unit cost, rather than utilization.10 The introduction of new drugs to treat hepatitis C was a large driver of the increase in 2014. Although the trend is up, specialty drugs represented only 16 percent of Part D drug spending in 2014, up from 11 percent in 2014.11 Only 2 percent of Part D enrollees used a specialty drug in 2014.

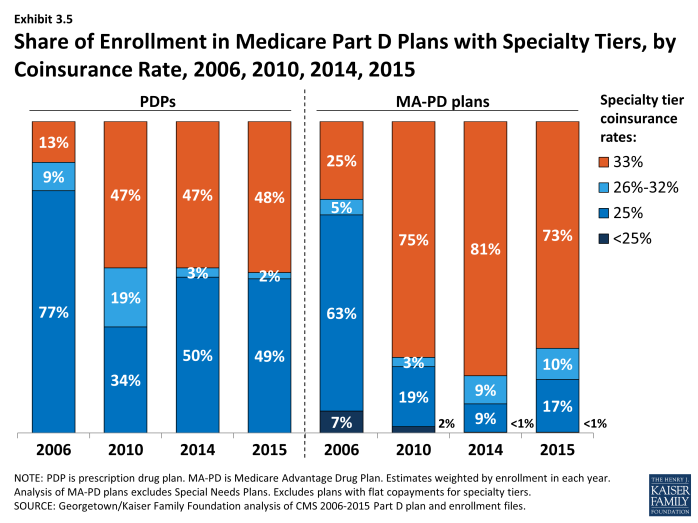

About half of PDP enrollees and most MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with a 33 percent coinsurance rate for specialty tier drugs. While CMS limits the coinsurance rate for drugs placed on a specialty tier to 25 percent, plans are allowed to impose higher cost sharing (up to 33 percent) for specialty tier drugs if offset by a lower deductible.12 In 2015, 48 percent of PDP enrollees with a specialty tier and 73 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees in a plan with a specialty tier are in plans charging the maximum 33 percent coinsurance for specialty drugs in the initial coverage period (Exhibit 3.5). By contrast, in 2006 only 13 percent of beneficiaries in PDPs and 25 percent of enrollees in MA-PD plans with specialty tiers faced a 33 percent coinsurance rate. Overall, 57 percent of PDP and MA-PD plan enrollees are liable for 33 percent coinsurance for specialty tier drugs in 2015—up from 16 percent in 2006.

Placing a drug on the specialty tier or on a non-preferred brand tier with high coinsurance can have significant cost implications for plan enrollees, at least before they reach the catastrophic coverage phase of the Part D benefit. A specialty drug priced at the $600 threshold will cost the beneficiary between $150 and $200 per month during the initial coverage period prior to the coverage gap. But monthly cost sharing for other common specialty drugs, such as Copaxone (for multiple sclerosis), Enbrel (for rheumatoid arthritis), Gleevec (for certain cancers), and Truvada (for HIV) can range from $300 to $2,000, before a beneficiary reaches the coverage gap or qualifies for catastrophic coverage. The cost for the first month of Sovaldi, a newly approved drug for hepatitis C, can exceed $5,000.13 For beneficiaries who exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold, the cost sharing is lowered to 5 percent of the drug cost for the remainder of the year.

Tiered Pharmacy Networks

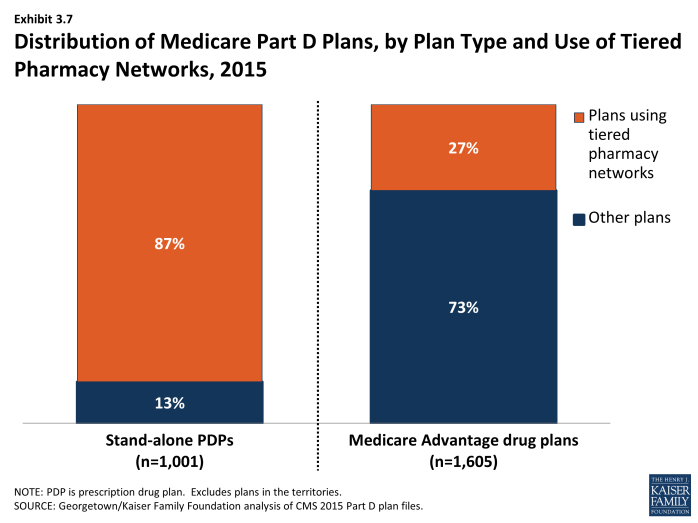

In 2015, 87 percent of all PDPs—representing 81 percent of all enrollees—have a tiered pharmacy network. By contrast, only 7 percent of PDPs (6 percent of enrollees) had a tiered pharmacy network in 2011 (Exhibit 3.6). Enrollees in these plans pay lower cost sharing for their prescriptions if they use pharmacies that offer preferred cost sharing.14 This approach to plan design started in 2011 with the market entry of co-branded PDPs featuring relationships with specific pharmacy chains, such as the Humana Walmart-Preferred Rx PDP (new in 2011) and the Aetna CVS/Pharmacy PDP (new in 2012). Many other plan sponsors designated a tiered network in 2013 or 2014, mostly without a co-branded relationship. The idea behind these arrangements is that Part D plans are able to negotiate discounted prices at certain pharmacies in exchange for higher volume of sales. The lower cost sharing creates an incentive for enrollees to use the designated pharmacies. CMS guidelines allow plans to assume use of preferred cost sharing in calculating whether cost sharing is actuarially equivalent to the defined standard benefit.

Tiered pharmacy networks have been employed much less often in Medicare Advantage. In 2015, only 27 percent of MA-PD plans (21 percent of enrollees) used tiered pharmacy networks (Exhibit 3.7). This lower rate may seem surprising given that Medicare Advantage plans generally limit networks for other types of providers. The faster adoption of this approach among PDPs compared to MA-PD plans may reflect the efforts of PDP sponsors to match practices of their competitors who were early adopters of this change.

Proportionally, the discounts in cost sharing for filling a monthly prescription in a pharmacy using preferred cost sharing is greater for generic drugs. The median discount (weighted by enrollment) is $3 for preferred generics and $5 for non-preferred generics, which represents a discount of more than half for these tiers. For brand drugs, the differential is much more modest in percentage terms but greater in dollars. The discount is $5 for the preferred tier and $10 for the non-preferred tier (5 percentage points and 13 percentage points, respectively, for plans that use coinsurance instead of copays). There are no differentials for the specialty tier.

For example, in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP sponsored by UnitedHealth, the copayment for a preferred brand drug is $20 in a designated pharmacy and $45 in another network pharmacy ($35 versus $60 for other brand drugs). Copayments in the Humana Walmart Rx PDP at a designated pharmacy are $1 for drugs on the preferred generic tier and $4 for drugs on the non-preferred generic tier, compared to $10 and $33, respectively, at other network pharmacies. Coinsurance differences for this Humana PDP are 20 percent versus 25 percent for a preferred brand drug and 35 percent versus 50 percent for a non-preferred brand drug.

Although the difference in cost for filling a single prescription is modest, the financial consequences for non-LIS Part D plan enrollees if they do not use pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing can add up for beneficiaries taking multiple brand-name drugs.15 An enrollee in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP who fills two brand drugs and one generic drug per month might pay an extra $624 over the year if she does not use one of the designated pharmacies; an enrollee in Humana Walmart Rx PDP might pay an extra $228.

In 2014 (the most recent available data), PDPs with tiered pharmacy networks designated only about 24 percent of their network pharmacies as offering preferred cost sharing.16 But the size of the preferred cost sharing networks varied enormously from 1 percent to 99 percent of plans’ overall networks. Overall, access to pharmacies is high. Most PDPs contract with at least 95 percent of all available pharmacies in their full pharmacy network.17 But generally plan sponsors do not offer the preferred terms to all pharmacies in their networks.

Limited information is available on the share of plan enrollees who fill prescriptions at pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing. A CMS analysis of 2012 claims data found that the share of retail claims in pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing ranged from 19 percent to 79 percent across 13 plans. For 7 of the 13 plans, the share of claims in pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing was 37 percent or less.18

For some PDPs, access to pharmacies with preferred cost sharing is limited. For some plans, there are few or no designated pharmacies within a reasonable travel distance.19 Medicare law requires that retail pharmacy networks as an entirety meet standards whereby certain shares of beneficiaries must have access to a network pharmacy close to their residence, with separate tests for urban, suburban, and rural areas.20 For example, 90 percent of beneficiaries in urban areas must have a network pharmacy within two miles of their home (90 percent within 5 miles for suburban areas and 70 percent within 15 miles in rural areas). CMS ensures that all plans meet these standards for their full pharmacy networks. But CMS found that 46 percent of PDPs or MA-PD plans would have failed if the test was applied just to the pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing.21 Plans were more likely to fail in urban area, whereas most plans would have met the standard in suburban and rural areas. If the urban access standard were widened from two miles to 4.5 miles, 90 percent of plans would have met the standard.

Plans sponsored by Humana illustrate the trend. In 2014, Humana’s PDPs on average designated only 10 percent of their network pharmacies as preferred, a lower rate than other national plan sponsors.22 Because Humana’s PDPs rely solely on Walmart pharmacies, access is lacking in urban areas where Walmart has no market presence.

In the call letter issued in April 2015, CMS indicated that it will monitor pharmacy networks and encourage plans to take action if they have too little meaningful access to the pharmacies that offer preferred cost sharing.23 Effective in 2016, the Medicare program intends to improve transparency by publishing information on plans’ access levels for the designated pharmacies. The agency will also require a sponsor to disclose in marketing materials if its network is an outlier on access standards. But the agency has not established specific access standards for tiered pharmacy networks offering preferred cost sharing, beyond the statutory standards that already apply to the overall networks.

Formularies and Utilization Management

In 2015, the average PDP enrollee is in a plan where the formulary lists 83 percent of all eligible drugs, the same as in 2013 and 2014 but slightly below the average in prior years. The scope of formulary coverage, however, continues to vary widely across PDPs in 2015. Some plans list all drugs from the CMS drug reference file on their formularies, while other PDPs list as few as 66 percent of these drugs.24 Even the most limited formularies, however, exceed the formulary requirements established under law and CMS program guidance.25 The seven largest PDPs range in formulary coverage from 74 percent to 89 percent of drugs in the reference file.26 The average MA-PD plan enrollee is in a plan with slightly more drugs on formulary (87 percent) than PDPs. Beneficiaries retain the option of requesting an exception to have the plan cover an off-formulary drug, or they can obtain the drug by paying the full purchase price out of pocket.

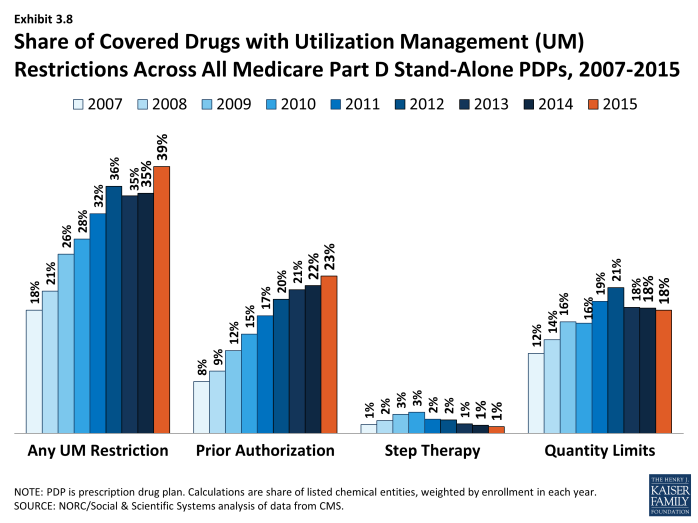

Since 2007, PDPs have applied utilization management (UM) restrictions to an increasing share of on-formulary drugs, increasing from 18 percent in 2007 to 39 percent in 2015 (Exhibit 3.8). Even if a drug is listed on a plan’s formulary, utilization management rules, including step therapy, prior authorization, and quality limits, may restrict a beneficiary’s access to the drug.27 In 2015, more drugs are subject to prior authorization than to other UM tools. On average across all PDPs (weighted for enrollment), prior authorization is applied to 23 percent of formulary drugs, about three times the use in 2007. Quantity limits (e.g., limiting a prescription to 30 pills for 30 days) are applied to 18 percent of drugs in 2015, whereas only 1 percent of drugs are subject to step therapy. MA-PD plans tend to apply UM restrictions to about the same share of drugs as PDPs.

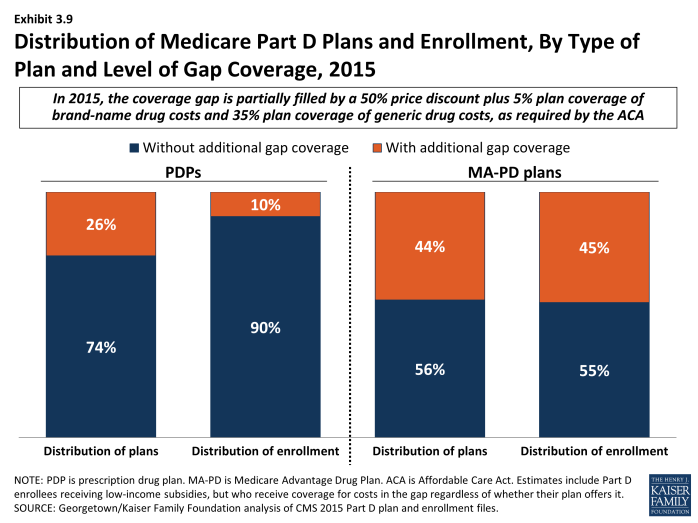

The Coverage Gap

In 2015, most PDPs (74 percent) offer no gap coverage beyond what is required by law; PDPs offering extra gap coverage cost more and have attracted fewer enrollees (Exhibit 3.9). In 2015, beneficiaries reaching the gap pay 45 percent of the full price for brand-name drugs in the gap (after a manufacturer price discount of 50 percent; plans pay the remaining 5 percent), and 65 percent of the cost for generics (plans pay the remaining 35 percent). Under current law, beneficiaries will face average cost sharing of only 25 percent for all drugs in the gap by 2020—the same as in the initial coverage period—effectively eliminating the coverage gap.

Plans offering gap coverage typically cover only a subset of drugs when enrollees are in the coverage gap. In past years, CMS has differentiated gap coverage by shares of drugs covered in the gap (few, some, many, or all). The agency terminated these descriptions starting in 2015 on the basis that they are no longer relevant as a result of phasing out of the coverage gap. In our analysis for past years, we classified plans labeled by CMS as covering few brands or few generics (defined as less than 10 percent of drugs in a particular category) as having “little or no coverage.” Because those distinctions are no longer available, some plans labeled as having gap coverage may have additional coverage for only a minimal share of drugs.

In 2015, 90 percent of all PDP enrollees are in plans without additional gap coverage beyond what is required by law (Exhibit 3.9). Overall, however, only 49 percent of PDP enrollees are potentially exposed to the gap in coverage if their spending exceeds the initial coverage limit. This lower percentage reflects the fact that LIS enrollees pay the same modest cost-sharing amounts in the gap as in the initial coverage period. In 2015, the vast majority of non-LIS Part D enrollees (84 percent) are enrolled in PDPs with no gap coverage beyond what is required by the ACA.

A larger share of MA-PD plans (44 percent) than PDPs (26 percent) offer additional gap coverage in 2015, and a much larger share of MA-PD plan enrollees than PDP enrollees are in such plans. Nearly half (45 percent) of MA-PD plan enrollees have at least some additional gap coverage beyond what the ACA requires, well above the 10 percent for PDP enrollees (Exhibit 3.9). The higher level of additional gap coverage among enrollees in MA-PD plans occurs largely because Medicare Advantage plans are able to use payments received from the government for providing benefits covered under Parts A and B to reduce cost sharing and premiums under Part D.28 Furthermore, because Medicare Advantage plans cover hospital and physician services and other Medicare benefits, they have stronger incentives than PDPs to offer at least some gap coverage to forestall the negative health and cost consequences that could arise if enrollees do not take their medications when they reach the gap. Despite these incentives, a majority of MA-PD plans offer no additional gap coverage. Overall, 77 percent of enrollees in PDPs or MA-PD plans are in plans with no gap coverage.