Medical Debt Among People With Health Insurance

Karen Pollitz, Cynthia Cox, Kevin Lucia, and Katie Keith

Published:

Introduction

An estimated 1 in 3 Americans report having difficulty paying their medical bills – that is, they have had problems affording medical bills within the past year, or they are gradually paying past bills over time, or they have bills they can’t afford to pay at all.1 Medical debt – and a host of related problems – can result when people can’t afford to pay their medical bills. While the chances of falling into medical debt are greater for people who are uninsured, most people who experience difficulty paying medical bills have health insurance. Medical debt can arise when people must pay out-of-pocket for care not covered by health insurance or to which cost-sharing (such as deductibles) applies. Medical debt might also result from health insurance premiums that individuals find difficult to afford.2 The consequences of medical debt can be severe. People with unaffordable medical bills report higher rates of other problems – including difficulty affording housing and other basic necessities, credit card debt, bankruptcy, and barriers accessing health care.

This report examines medical debt through case studies of nearly two dozen people who recently experienced such problems, and reviews their experiences in light of other studies and surveys about medical debt. It focuses primarily on problems of medical debt among insured individuals and families. Most of the case studies feature people who struggled with medical debt while covered under health plans that would be considered typical and mainstream today. The report concludes with a discussion of how provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) may influence the factors that contribute to medical debt.

Study Approach

In order to gain more detailed insights into the problems and causes of medical debt, we collaborated with a national, non-profit credit counseling agency to identify individuals struggling with medical bills and study their experiences. We partnered with ClearPoint Credit Counseling Services (ClearPoint),3 a non-profit consumer credit counseling agency based in Atlanta, Georgia, that provided counseling and debt management services to over 200,000 people nationwide in 2011. Most ClearPoint clients self-refer when they are in financial distress, for example, when they can no longer make minimum payments on loans and debts or when they’re contacted by debt collectors. Others are referred for recommended or required counseling, for example, when they apply for mortgage foreclosure relief or file for bankruptcy. In 2011, roughly 12 percent of ClearPoint clients identified medical bills as the first or second leading cause of their financial difficulties.

We developed an online screening survey to send to clients who had recent difficulty paying medical bills and for whom email addresses were available. The survey requested information not already collected by ClearPoint, such as insurance status and coverage changes, the total amount and types of medical bills, and whether illness triggered other problems, such as job loss or missed rent or mortgage payments. It was also used to identify individuals with medical debt who were willing to participate in in-depth interviews. Of the 129 respondents to the screener survey, 23 completed hour-long interviews providing detailed information about their medical bills, insurance coverage and financial status. While neither ClearPoint clients – nor survey respondents or interview subjects – can be considered representative of the broader population, their circumstances are consistent with findings of other studies of medical debt. This report examines the case studies in light of these other, broader studies.

A brief overview of each case study is displayed in Table 1. Stories of the 23 people interviewed appear in the Appendix. Several key characteristics of these individuals and their circumstances are summarized in Table 2.

| Table 1: Case Study Overview | |||||||

| Name * | Age | Occupation | Income (% FPL) | Insurance Source | Amount Bills | Bill Timeline | Whose Bills? |

| Ben | 59 | Trucker | $68,000 (590%) | Large employer | $5,000 | 2012 | Self |

| Kris | 56 | Construction | $38,000 (330%) | Large employer | $6,000 | 2011 | Self |

| Kieran | 43 | Car dealer | $75,000 (240%) | Large employer | $20,000 | 2007-2011 | Spouse, children |

| Sonya | 49 | Homemaker | $85,000 (360%) | Large employer | $60,000 | 1994-2011 | Self, son |

| Stuart | 48 | Sales manager | $74,000 (315%) | Large employer | $6,000 | 2010-2011 | Spouse |

| Duncan | 45 | Teacher | $50,000 (255%) | Large employer | $10,000 | 2010-present | Spouse |

| Maisy | 51 | Librarian | $66,000 (280%) | Large employer | $30,000 | 2004-2011 | Spouse |

| Richard | 36 | Financial adviser | $130,000 (550%) | Large employer | $30,000 | 2007-2011 | Self, daughter |

| Dorothy | 59 | Teacher | $34,000 (300%) | Large employer | $4,500 | 2011-2012 | Self |

| Gwen | 57 | Medical transcriptionist | $22,000 (140%) | Large employer | $40,000 | 2011 | Spouse |

| Dillon | 48 | Repairman | $59,000 (529%) | Large employer | $19,000 | 2003-2010 | Self |

| Jeanne | 64 | Retired | $24,000 (220%) | Large employer | $2,000 | 2010-2011 | Self |

| Safiya | 22 | Restaurant worker | $10,000 (90%) | Large employer | $5,000 | 2011 | Self |

| Connie | 47 | Nurse | $50,000 (210%) | Small employer | $36,000 | 1996-present | Spouse, children |

| Elsie | 37 | Writer | $60,000 (310%) | Small employer | $20,000 | 2007-2009 | Self, child |

| Katherine | 46 | Customer service rep | $19,200 (167%) | Small employer | $35,000 | 2006-2009 | Self |

| Morgan | 51 | Entertainer | $51,000 (220%) | Non-group | $35,000 | 2008-2012 | Self |

| Millie | 52 | Realtor | $65,000 (340%) | Non-group | $20,000 | 2007-present | Self |

| Louise | 58 | Unemployed | N/A | Interrupted | $50,000 | 2005 | Self |

| Gillian | 59 | Artist | $10,000 (90%) | Interrupted | $10,000 | 2009-2010 | Self |

| Claire | 44 | Unemployed | N/A | Uninsured | $50,000 | 2008-2011 | Self |

| Tanisha | 47 | Unemployed | N/A | Uninsured | $7,000 | 2008 | Self |

| Charlene | 51 | Teller | $38,000 (195%) | Uninsured | $23,000 | 2010-2011 | Self, daughter |

| * Names and certain other characteristics of individuals have been changed to protect their identity.* Names and certain other characteristics of individuals have been changed to protect their identity. | |||||||

| Table 2: Case Study Highlights | ||

| Characteristic | Number of Cases | |

| Age | < 30 | 1 |

| 31-40 | 2 | |

| 41-50 | 9 | |

| 51-64 | 11 | |

| Amount of medical bills/ medical debt | < $5,000 | 4 |

| $5,001 – $10,000 | 5 | |

| $10,001 – $20,000 | 4 | |

| $20,001 – $50,000 | 9 | |

| > $50,000 | 1 | |

| Time period bills incurred | < 1 year | 6 |

| 1-2 years | 4 | |

| > 2 years | 13 | |

| Whose bills? | Self or one family member | 17 |

| Multiple family members | 6 | |

| Household income | <$20,000 | 6 |

| $20,000 – $50,000 | 7 | |

| $51,000 – $75,000 | 8 | |

| $76,000 – $100,000 | 1 | |

| >$100,000 | 1 | |

| Illness triggered income loss? | Yes | 18 |

| No | 5 | |

| Health insurance source | Large employer | 13 |

| Small employer | 3 | |

| Non-group | 2 | |

| Uninsured | 3 | |

| Coverage interrupted | 2 | |

| Health plan deductible (per person)* | <$500 | 3 |

| $501 – $1,000 | 5 | |

| $1,001 – $2,500 | 3 | |

| >$2,500 | 6 | |

| Significant out-of-network costs* | Yes | 7 |

| No | 11 | |

| Other medical debt impacts | Damaged credit | 21 |

| Lost home/home equity | 6 | |

| Deplete retirement, other savings | 13 | |

| Other financial deprivation | 9 | |

| Bankruptcy | 15 | |

| Access to care barriers | 5 | |

| * Insured cases only | ||

Key Interview Themes

Together, these cases reveal cross cutting themes and insights into the problem of medical debt, its causes and potential solutions.

Medical debt can affect almost anyone. People we interviewed ranged in age from 20s to 60s and lived in various states. Some were single, others headed families. Their annual incomes ranged from less than $10,000 to more than $100,000. Most were insured continuously in job-based group plans; a few were covered in non-group policies. Two others were insured at the outset of illness, and then lost coverage. Three were uninsured the entire time. For most in our study, this instance of medical debt was the first time they had experienced serious financial or credit problems. The onset of an illness, accident, or pregnancy generated expenses that they did not anticipate and which they were unprepared to pay. Some faced tens of thousands of dollars in medical debt. For others, just a few thousand dollars of bills proved unaffordable, particularly when a chronic illness meant bills would continue year after year.

Among insured individuals, unaffordable medical debts resulted primarily from cost-sharing for care covered by their insurance. Some insured people faced exceedingly high levels of health plan cost-sharing (e.g., $10,000 or more per person per year). For most, though, much smaller amounts proved unaffordable. Some with limited incomes and/or cash savings had trouble paying even a few thousand dollars. Others might have been able to handle a single year of cost-sharing liability for one person, but when treatment spanned two plan years or when more than one family member made significant claims, cost-sharing expenses multiplied and became unaffordable.

Out-of-network charges also proved burdensome. Typically health plan coverage is less for care rendered by non-network providers. Many people inadvertently received non-network care while hospitalized. Though they had selected a network facility, other hospital-based professionals whom they did not and could not select – such as anesthesiologists and emergency physicians – were not in network. As a result, patients owed much more out-of-pocket than expected.

Coverage limits and exclusions and unaffordable premiums also caused problems. In some cases, patients were left to pay bills for care their policy simply didn’t cover. Some also fell into debt trying to pay health insurance premiums they couldn’t afford.

Related problems can often exacerbate medical debt. Often significant health events triggered loss of income, rendering unaffordable bills that might otherwise have been manageable. For the vast majority of those interviewed, the medical event associated with the debt also left the patient unable to work or prompted a working family member to quit or reduce hours in order to become a caregiver. Significant health events can also compromise a person’s ability to manage the paperwork of medical bills. Nearly all those interviewed emphasized how the sheer volume of bills during a major health event was overwhelming. They had trouble tracking what had been paid, what was owed, and what had been transferred to collections. Their task was made more difficult by confusing provider bills and insurance company statements that lacked key information. Most didn’t know where to seek help, and the burdens of illness made it harder to resolve problems on their own.

Once it starts, medical debt can be hard to stop. Most of those interviewed struggled for years to climb out of medical debt, and for some, new debts arose even after prior ones had been resolved. This was the case for people with chronic health conditions as well as for people with high medical bills from a single health event. Fifteen of those interviewed used credit cards to pay at least some of their outstanding medical bills, and resulting finance charges increased their debt.

Medical debt can trigger other severe consequences. The economic and personal impact of medical debt can be devastating. Most of those interviewed ended up declaring bankruptcy as a direct result of high medical bills. Others depleted retirement or college savings, lost homes to foreclosure, or did without basics such as home heat. Almost all suffered damage to their credit rating. Some eventually bounced back from medical debt problems while others permanently reduced their standard of living. Some people experienced barriers to care. Nearly all expressed a strong ethic to pay their bills and deep regret, even shame, to be in medical debt.

Report

Incidence of Medical Debt

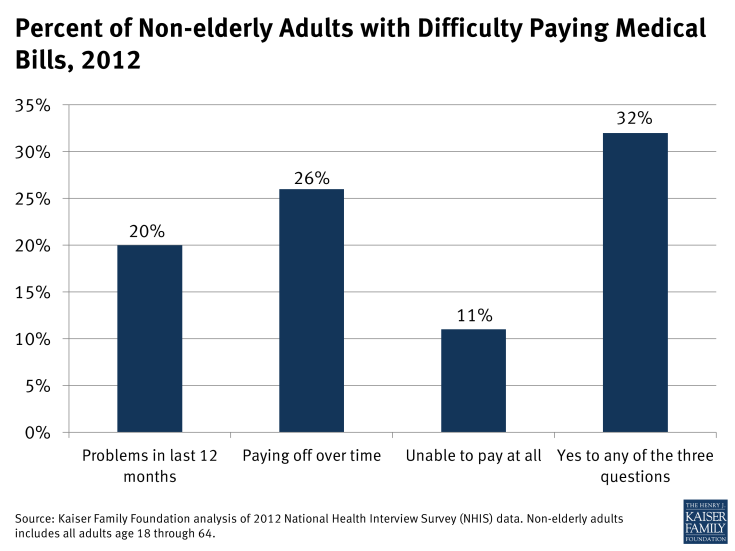

Our analysis of 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data, presented below as context for our case studies, finds the problem of medical debt is widespread. This survey finds that 20 percent of non-elderly adults reported difficulty paying medical bills in the previous year. When the question is broadened to include problems paying medical bills over a longer period of time, or inability to pay some medical bills at all, nearly one in three non-elderly adults (32 percent) report having medical bill problems.

In our survey of ClearPoint clients, we identified people who had faced unaffordable medical bills during the prior year. Many who answered yes, however, had incurred medical bills much longer ago and were still struggling to pay them, or had only recently paid them or discharged old debts through bankruptcy.

The total dollar amount of medical debt held in the U.S. is difficult to measure. Medical debt may be masked as other forms of debt, for example, when someone uses a credit card to pay a doctor bill, the amount reflected on a credit report will indicate credit card debt, not medical debt. Similarly, when a person skips a mortgage payment in order to pay a medical bill, the resulting bank debt typically would not be counted as medical debt.

Characteristics of people interviewed for our case studies fall within the range of what broader survey data tell us about medical debt. Our analysis of NHIS data finds that individuals and families across a range of household incomes, ages, employment, family, and insurance statuses report difficulty paying medical bills.

Income – Difficulties with medical bills are more pronounced among the poor and near poor – approximately 4 in 10 nonelderly adults with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level reported problems affording medical bills – but people with incomes at or above 400% of the federal poverty level also struggle with medical debt.1 People we interviewed had incomes ranging from 75% to over 560% of the federal poverty level.

Employment– People who are unemployed report somewhat higher rates of medical bill problems (35%) compared to people who work full time (30%). Twenty of the people we interviewed worked full time or their spouse worked full time.

Age and Family Size – Medical bill problems affect people regardless of age. Among the non-elderly, medical bill problems are more likely as family size increases; 37 percent of households with 4 or more members experienced medical bill problems in 2012, compared to 25 percent of single person households. People we interviewed ranged in age from their 20s to their 60s. Nine were non-married adults; four were in two-person households; ten were in households of three or more.

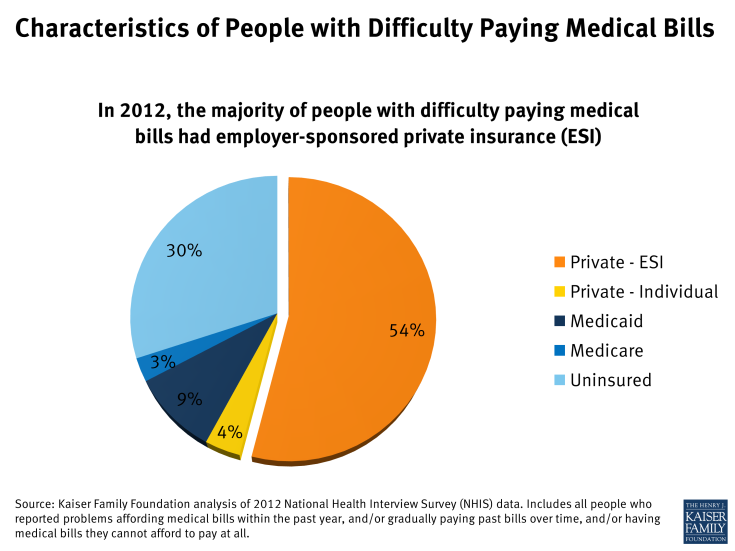

Health Insurance Status – Among non-elderly adults, nearly half (45%) of the uninsured report problems paying medical bills, compared to roughly one-in-four privately insured individuals. The vast majority of people with medical debt (70%) are insured. People with employer-sponsored coverage make up the bulk (54%) of medical debt cases. Of the people we interviewed, 16 were covered under job-based group health plans. Two were covered by individual policies. Five were uninsured for most or all of the time they were incurring unaffordable medical bills (including one who became uninsured when her individual policy was rescinded.)

How Does Medical Debt Become a Problem for People with Health Insurance?

Similar to the overall population, most of those we interviewed were insured as they incurred medical debt – most of them under job-based group health plans. All expected that health insurance would protect them from financial ruin if they would ever face a serious illness or injury, but that turned out not to be the case. Various features of their coverage contributed to medical debt problems, and are examined in more detail below.

In-Network Cost-Sharing

By far, the leading contributor to medical debt among people interviewed was cost-sharing for covered services received by in-network providers and facilities. Of the 23 people interviewed 17 reported high cost-sharing burdens. To some extent, “high” can be measured objectively, but affordability also depended on an individual’s income and other characteristics.

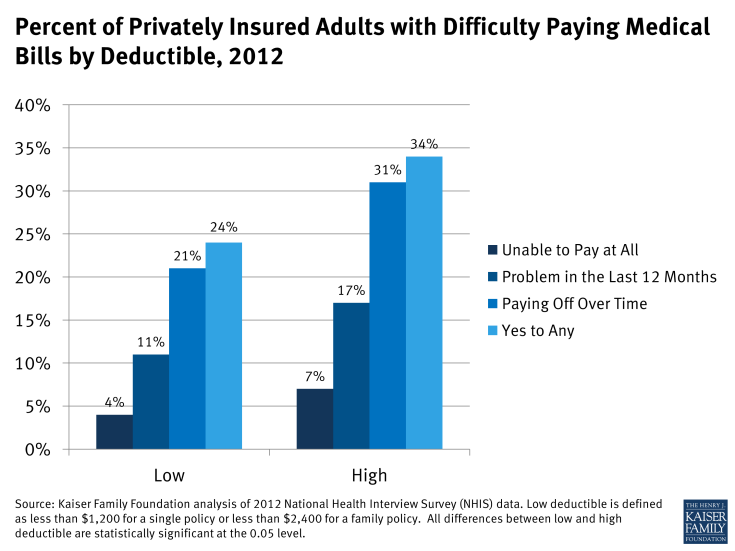

Case studies illustrated that cost-sharing need not be extremely high to be unaffordable. However, other research confirms that medical debt problems among the insured increase with higher levels of cost-sharing. For example, NHIS data show people in higher-deductible health plans are more likely (34%) to have difficulty paying medical bills compared to people in lower-deductible health plans (24%).

The amount of cost-sharing required under health insurance plans has risen steadily for years. As recently as 2006, only 10 percent of covered workers in group health plans faced an annual deductible $1,000 per person or more; today it 38 percent.1 For nine of our interviewees, the health plan annual deductible was $1,000 per person or less.

Figure 3: Percent of Privately Insured Adults with Difficulty Paying Medical Bills by Deductible, 2012

This trend in rising cost-sharing reflects a tradeoff in affordability of premiums and level of protection provided by a plan. However premium savings to an individual or family can be more than offset if they must satisfy the annual deductible or out-of-pocket limit on cost-sharing. Studies find that among people reporting problems paying medical bills, the average medical debt for the family was $6,500 in 2010.2 While many of the people we interviewed had medical bills in excess of that amount, six had unaffordable medical bills that totaled $5,200 or less. From their experiences, we observed several reasons why even a few thousand dollars in annual, in-network cost-sharing proved problematic:

Medical bills high relative to income and savings

Studies of medical bill burdens often use as a benchmark bills that exceed 10 percent of household income, though this level was selected somewhat arbitrarily.3 Twenty of the people we interviewed had medical bills exceeding this threshold. For those with limited incomes, even modest amounts of cost-sharing were unaffordable. Prescription drug copays were a struggle for Dorothy, for example. She earned $34,000 annually. The copays for her drugs totaled $150 each month, or more than five percent of her annual income. Then, when she was unexpectedly hospitalized and had to pay a $2,000 deductible in addition, the bills were simply more than she could manage.

None of the individuals interviewed had sufficient savings to pay their portion of covered, in-network medical bills. In this respect, they were similar to most Americans. According to the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, most U.S. households have very limited liquid assets (checking, savings, and money market account balances). See Table 3. The amount of liquid assets declines sharply as income declines. For those with incomes below 400% of the federal poverty level (two-thirds of the U.S. population), most have far less than $3,000 cash on hand. Taking into account other unsecured consumer debt (e.g., credit card and medical debt, but not mortgage or auto loans), most households with incomes below 400% of FPL have net negative financial assets. That is, their consumer debt exceeds their cash on hand. As a result, even modest deductibles and copays could pose affordability problems, particularly if cost-sharing expenses recur, as for chronic health conditions.

Among households with higher incomes – greater than 400% FPL – liquid assets are higher. The median amount of cash on hand for this income group is $12,000. Taking into account other unsecured consumer debt, however, most have net liquid assets of $5,200 or less.

|

Table 3. Median Household Liquid Assets and Net Financial Assets by Household Poverty Level

|

||

|

Income

(% Poverty Level)

|

Liquid Assets

|

Net Financial Assets

|

|

<100%

|

$100

|

$0

|

|

100% – 250%

|

$670

|

-$488

|

|

250% – 400%

|

$2,740

|

-$3,000

|

|

>400%

|

$12,000

|

$5,200

|

|

Source: KFF Analysis of Survey of Consumer Finances data, 2010.

|

||

Typical group health plan cost-sharing levels today exceed the amount of liquid cash balances most households have on hand. In group health plans, the average annual deductible in 2013 is $1,135 for single coverage; then additional cost-sharing expenses applied until the annual OOP maximum is reached. In 56% of group health plans today, the annual OOP maximum is less than $3,000 for a single person.4 Thus cost-sharing resulting from a single surgery could rapidly deplete liquid cash assets for most people. As high-deductible health plans become more prevalent, potential problems compound. In 2013 38% of workers have annual deductibles in excess of $1000 (single) and 43% have annual OOP maximums greater than $3,000. For many people covered under these plans, even with income above 400% FPL, an extended illness or chronic condition could easily result in unaffordable medical bills.

Cost-sharing “multipliers”

Many health plans are identified by the level of their annual deductible – for example, the “PPO 500.” The number signifies a single person’s potential deductible expense for a single plan year. In evaluating the protection offered by a policy, people may tend to focus on a single number – the annual deductible or annual limit on out-of-pocket cost-sharing (the OOP limit) – without realizing that this does not necessarily represent the extent of possible cost-sharing liability. In fact, individuals and families can incur multiples of these expense amounts, as several people we interviewed experienced.

Some examples of cost-sharing “multipliers” are listed below.

Treatments spanning two plan years – Several people interviewed had treatment that began toward the end of one plan year and continued into the next, effectively doubling their cost-sharing liability for a single treatment episode. George, for example, had surgery scheduled for the last month of a plan year; the following month he experienced post-operative complications, necessitating a second surgery. As a result he satisfied two annual deductibles and one and one-half annual OOP limits within a period of 4 months. Some health plans (though not George’s) include a carry-over feature that credits care received in the final months of a plan year toward the next plan year’s annual deductible.5

Family-level cost-sharing – Under family policies, cost-sharing expenses can also double if more than one person makes significant claims in a year. Elsie, for example, was covered by a health plan with $1,000 deductible per person. Once her son was born, his expenses were subject to a separate $1,000 deductible. Beyond the deductible, both mother and son were liable for additional cost-sharing expenses, up to an annual OOP limit. The year after giving birth, Elsie required surgery and her son was hospitalized twice before he turned three. By then, the family cost-sharing bills reached $20,000.

Cost-sharing for chronic conditions – Finally, it was common for cost-sharing bills to accumulate year after year when people had chronic conditions. While some could manage bills for a while, over time financial burdens compounded and became too great. Sonya, for example, struggled with repeated deductibles and copays over 16 years as she sought treatment for her child’s autism. Seventy-two million working age Americans have at least one chronic health condition.6 People with chronic conditions are much more likely to have high financial burdens for two consecutive years (29% to 56%, depending on the chronic condition) compared to those with no conditions or acute conditions (14% to 15%).7

Extremely high cost-sharing

Some people were covered by health plans that required very high cost-sharing for covered services, beyond what is required under typical health plans or what would be allowed under private plans starting in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act. For example, three of the people interviewed were covered by health plans with an annual out-of-pocket (OOP) limit on cost-sharing liability in network of $10,000 per person. One of these was a non-group plan; the other two were job-based group plans.

The health plan OOP maximum generally limits the amount of cost-sharing a person is responsible for in a year for in-network care. However, in at least two cases, the OOP limit was not, in fact, the maximum amount of cost-sharing that could apply. Under Gwen’s plan, for example, the OOP limit was in addition to her $3,000 annual deductible, not inclusive of that amount. Under Richard’s plan, the OOP limit did not apply to outpatient copays. His $40-per-visit-copay for physical therapy (three times per week for an extended period) added almost another $500 per month ($6,000 per year) to his medical bills.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation 2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey, most employer sponsored health plans have an annual OOP maximum on cost-sharing. For most plans, the annual OOP maximum is less than $3,000 per person; only 4 percent of covered workers are in plans with an OOP maximum of $6,000 or more. Under job-based plans today, however, most OOP limits are not all-inclusive. For about one-in-three workers enrolled in PPO plans with an OOP limit, the annual deductible does not count toward the OOP limit. And for most workers in plans with OOP limits today, cost-sharing for prescription drugs does not count toward the OOP limit.8

Out-of-Network Care

Another common problem observed in the case studies involved medical bills arising from care received out-of-network. Seven of those interviewed had unaffordable medical bills for out-of-network care. These bills proved particularly problematic for several reasons:

Fewer cost-sharing protections

Some health plans – usually HMOs – require all care to be received by network providers in order to be covered. Most others will cover out-of-network care, but at a lower level. Gwen and George’s case offered an example: Under their plan, a $3,000 annual deductible and $10,000 OOP maximum (in addition to the deductible) applied for in-network care; but amounts doubled for out-of-network care. With these high limits, George incurred $26,000 in out-of-network cost-sharing in less than one year.

“Inadvertent” out-of-network care

Often people received out-of-network medical bills from providers whom they never met or did not choose. This happened frequently among those who were hospitalized. Ben, for example, incurred unexpectedly high medical bills from a surgery, and almost one-third of what he owed was to the anesthesiologist, whom he met for the first time the day of the operation. Ben had been careful to select a surgeon and a hospital in his plan network; it didn’t occur to him that other doctors practicing within the hospital might not also be in network. “I found out one thing. Anesthesiologists are not part of the medical group. They’re not with anybody’s network. I guess they figured out if you need surgery, hey, you’re stuck with us! That was a surprising thing to me. It was only later I realized they’re not in any network.” Kris was another person who chose an in-network facility, but was billed by doctors working in the hospital who weren’t in the same network. “Most of what I owe is to doctors who treated me while I was hospitalized and I never saw them again out of the hospital. One allergist’s bill was close to $1,200 – that was my portion. I wish I knew why he was so expensive. He just came in the room twice and gave me a sheet saying what I should and shouldn’t do – he didn’t even write me a prescription. The doctor who was treating me in the hospital wanted to consult with this allergist. I didn’t contact him directly or select him.”

Gwen and George faced a somewhat different situation. Following surgery, George was so frail his doctor recommended recovery in the inpatient rehabilitation unit of the hospital. However, that unit was independently owned and operated by a separate company that did not participate in the plan network. Gwen was told the unit was out-of-network, but in light of her husband’s frail condition (and in light of substandard care they believed he had received previously from another in-network rehab facility) she felt she had no other choice. George’s share of the inpatient rehab bill alone was $23,000.

In general, hospitals do not require physicians to participate in the same plan networks as a condition of receiving hospital privileges, and health plans do not require hospitals to have such agreements with hospital-based physicians, though most plans acknowledge these specialties are critical to an adequate network precisely because patients have no choice in selecting them.9 Health plans report difficulty negotiating network agreements with hospital-based physicians (such as anesthesiologists, radiologists, and emergency physicians) and note these specialties are the most aggressive in seeking higher fees and typically have exclusive agreements with one or more hospitals in an area.10

Balance billing

In addition to Ben and Kris, Kieran had difficulty paying unexpected high medical bills that included balance billing. His wife, Jenna, experienced complications during her pregnancy and was hospitalized several times. Several doctors who treated her and the baby were out-of-network and billed the family more than insurance determined was reasonable. Out-of-network providers are not required to limit charges to the amount allowed by a health plan. When they don’t, patients can be liable for the balance of the charge above what their health plan allows in addition to higher cost-sharing. U.S. consumers pay an estimated $1 billion annually in balance billing charges.11 A study of Californians covered under job-based group plans found 11 percent experienced balance billing; among those who were hospitalized, 17% received at least some out-of-network care.12

Interestingly, though George owed thousands of dollars for his non-network care, he incurred very few balance billing charges. The couple’s health plan participated in a “Multiplan” agreement – essentially an independently organized provider network that supplemented the regular plan network. Nearly all of the non-network providers who cared for George participated in the Multiplan network. As a result, George’s health plan agreed to reimburse based on that network’s fee schedule and the providers agreed to refrain from billing above that amount.13

Another interviewee, Morgan, also escaped balance billing from non-participating providers. Morgan also chose an in-network hospital for his surgery, and then inadvertently received out-of-network care from doctors who practiced in that hospital. However, Morgan’s insurance policy included a feature that protected him from balance billing from non-network providers while in a network hospital. His insurance simply paid the entire billed charge of the non-network doctors. Morgan didn’t realize his policy included this feature until the bills arrived, though was thankful for it. Health insurers generally are not required to include such coverage of non-network balance billing.

Health Plan Coverage Limits or Exclusions

For several people interviewed, medical debt arose when health insurance simply did not cover the care they needed. Dillon, for example, was hit by an uninsured motorist in 2003. The accident totaled his truck and left him with chronic back pain and depression. His insurance, through a large employer health plan, didn’t cover the extensive physical therapy he needed; nor did it cover dental care needs – which, although unrelated to the accident, were also extensive. Dillon estimates his unpaid medical bills over several years reached $10,000-$20,000.

Maisy’s medical debt related to her husband’s mental health conditions. He suffered from panic attacks, depression and addiction, requiring extensive inpatient treatment and rehab over a period of six years starting in 2002. Claims following a suicide attempt weren’t covered by her large employer health plan, which excluded treatment for self-inflicted injuries. Maisy also expressed concern that under her policy, other inpatient stays were subject to strict utilization review and her husband was rarely allowed to remain inpatient for more than a few days. She worried this limited the effectiveness of treatment, prolonging his illnesses. By 2010 his medical bills reached nearly $30,000 and Maisy had to declare bankruptcy. Mental health parity regulations issued in 2010 prohibited separate day and visit limits on mental health care different from those applied to other covered benefits. Final regulations issued in 2013 also prohibit exclusions for treatment related to mental illness, such as attempted suicide.14

Safiya’s medical debt resulted when she reached the annual limit of coverage under her job-based health plan. Her employer, a fast food chain, provided a so-called “mini med” plan that limited coverage to just a few thousand dollars per year. When she found a breast lump and needed a biopsy, she quickly reached her plan limits and was left to pay $5,200 out-of-pocket. Another woman, Katherine, reached the lifetime limit on her policy in 2006 after she had been in extensive treatment for breast cancer. She spent several years trying to pay the non-covered medical bills, which totaled $35,000, but ultimately had to file for bankruptcy.

Sonya’s child was diagnosed with autism at age four. She said her family has “lived medical bills ever since.” She sought care from various specialists, speech therapists, and alternative medicine practitioners. In a number of cases treatments were simply not covered by her health plan provided through her husband’s large employer. Her medical bills for the autism treatment, in addition to those incurred by other family members, reached $60,000 over 16 years, leading her to file for bankruptcy.

Unaffordable Premiums

Two people we interviewed amassed substantial medical debt as a result of their non-group health insurance premiums.

One was Morgan, 51, a self-employed artist in Tennessee. Since 2005, he has been covered by a non-group policy he purchased for himself and his family. Initially he found both the premiums and cost-sharing affordable. But over the years, premiums increased steeply and Morgan tried to offset increases by raising the annual deductible. By 2009 his monthly premium for family coverage had reached $1,200 and his annual deductible was up to $5,000 per person. That year Morgan learned he had prostate cancer. Surgery was scheduled late in the year, so he had to satisfy two annual deductibles within a few months. He used credit card cash advances to pay the insurance premiums, but finance charges quickly inflated what he owed. They used nearly all of his retirement savings (about $10,000) to catch up, and then fell behind again. In mid-2010, he made the difficult decision to drop his wife from the policy, which cut the premium in half. By that time, though, their debts had reached $35,000. A few months later, the family filed for bankruptcy. Morgan describes his situation this way,

“Some people just drop coverage and go to the ER and pay nothing. But I was trying to do the right thing and stay insured. It’s so frustrating that I came close to ruining myself financially to do that. I spent thousands keeping my family insured. I have friends in Canada. They’re shocked to hear I pay more for health insurance than for my mortgage. It’s unnerving at times to look at the numbers. When I do my taxes and enter my health insurance costs, my tax software says ‘Are you sure? This seems high.’ Like a slap in the face. One year my health expenses were over $20,000 and my adjusted gross income was $25,000.”

Other Factors Unrelated to Insurance

Case studies revealed other factors that contributed significantly to medical debt. Serious illness can often be associated with a decline in income, making it harder for people to afford medical bills. In addition, people faced with serious illness were hampered in their ability to track medical expenses, challenge denials and correct mistakes, adding to what they owed. Finally, provider collections practices, as well as patients’ personal desire to pay their providers, led many people to rely on credit card financing or other drastic financial measures that had the effect of compounding their debt problems.

Income loss due to illness

In 18 of the 23 case studies, a significant reduction in household income resulted when the patient was too sick to work or a working family member had to quit or reduce hours to care for the patient. This frequently happens when a serious illness or injury occurs. For example, research finds that between 40 and 85 percent of cancer patients stop work during initial treatment, with absences ranging from 45 days to six months.15 Another study found that breast cancer survivors’ income fell on average by $3,600 five years after diagnosis; by contrast, a typical worker’s earnings increase over a five-year period, on average by $1,800.16 People interviewed for this report cited income loss as a key factor making it harder to afford the sudden onset of medical bills.

Kieran and Jenna’s struggled to pay more than $20,000 in medical bills from her illness and complicated pregnancy, and struggled even more when she had to quit her job due to illness. That cut the income for this family of six from $90,000 to $70,000 annually. Kieran emphasized what the loss of that second income meant. “With four kids, there’s always something – lunch money, something – and we couldn’t make it without her pay. Then when the medical bills started, things got out of control.” He took a part time job at CarMax and he and his son mowed lawns on weekends, but they had to cut back on a lot. “When my son broke his glasses, he had to wait a year before we could afford to get new ones. None of us went to the dentist for two years. We let one of the cars go.” Eventually Kieran and Jenna had to declare bankruptcy.

For Richard and his family, the income drop wasn’t as great, but the end result was similar. Richard suffered a traumatic leg fracture during a sporting event in 2007. At the time his $130,000 annual income provided a comfortable living for his family of four. But the leg injury required repeated surgeries, some with complications, and extensive physical therapy over the next four years. During extended treatments Richard had to go on short term disability, reducing his income to just $500 per week. He estimates he lost $12,000 in earnings in 2007, $6,000 in 2010, and almost $5,000 in 2012. Over those years, his medical bills reached $30,000, and he had to file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy. Under the court order, Richard must pay $1,000 per month to his creditors for five years.

Challenges to effective self-advocacy

Nearly all of those interviewed commented on the difficulty of managing medical bills. Most described the sheer number and frequency of bills and statements they received as “overwhelming.” Most also found bills and insurance statements were confusing or failed to provide sufficient information to describe a claim, what had been paid, what was still owed, and why. Several commented on how difficult it was to distinguish between new bills and repeated invoices for older, unpaid bills. Others observed that while the initial provider invoice would list and describe each billed service, subsequent invoices for unpaid balances usually didn’t itemize, instead just showing the total dollar amount owed.

Of those we interviewed, Stuart was one of the most meticulous in managing medical bills. His wife required several specialized surgeries over two years that had to be performed at a university hospital, 60 miles from their home. Between worrying about his wife and money and driving 120 miles per day, Stuart said managing the bills was a struggle. He described receiving multiple bills from the same provider. One bill, from a radiologist for a scan, appeared to be a duplicate of one Stuart had already paid so he set it aside. Only when he heard from a collections agent several months later did he realize the bill was for a separate scan. During that period, Stuart also needed a screening colonoscopy for himself. The ACA requires this screening service to be covered in full, but when the insurance statement came, the deductible had been incorrectly applied.17 When he called the insurer he was told it was his responsibility to work with his doctor to resubmit the claim with additional documentation in order for cost-sharing to be waived. Eventually Stuart got this sorted out, too, but with everything else going on it took effort. As he put it, “I’m a pretty easy going person, but I can understand how some people go postal over this stuff.” Stuart’s state operates a Consumer Assistance Program that will help residents resolve disputes and appeal denied claims, but he was not aware of this program.

Most others interviewed were not able to effectively track bills and resolve mistakes, including Gwen, who works in the health care industry and considers herself knowledgeable about health claims. But between caring for her frail husband and working full time as the sole breadwinner, she simply couldn’t manage. According to records Gwen provided, she received 125 different bills over a four-month period. Two claims were for ambulance transportation, one of which was denied. Gwen doesn’t know why. The insurance statement says non-emergency ambulance services are not covered, though an earlier ambulance claim was covered; it would appear the second claim was coded differently, but the statement doesn’t provide sufficient information to know for sure. Gwen could have appealed this denial, but didn’t pursue the matter. She also could have appealed her health plan’s decision to cover George’s inpatient rehab care out-of-network on the grounds that no other in-network facility was able to provide the level of care George needed, but she simply lacked the time and energy.

Studies show that consumers often don’t – or can’t – effectively resolve disputes with health plans or other payment errors. A Kaiser Family Foundation national survey of consumer experiences with health plans found a majority (51%) of insured, non-elderly adults reported some type of problem with their health plan, such as claims denials or difficulty obtaining referrals. Most consumers experiencing a problem had to try for a month or longer to fix it or they couldn’t satisfactorily resolve it at all.18 Especially when people are sick, managing insurance problems can be a challenge and many give up. Another study found that even when problems generated out-of-pocket costs to the patient of more than $1,000 or led to a serious decline in health, fewer than 40 percent of individuals complained to their health plan, and only rarely (3%) did they file complaints with state regulators.19 Consumers report they want and need help, but many don’t know where to turn. In the Kaiser survey, 89% of consumers didn’t know the agency that regulates health insurance in their state; 84% wanted an independent entity where they could seek help.

Medical debt collections

Most of the people we interviewed ended up in debt collections. Typically hospitals and other health care providers expected to be paid within 90 days of invoice. After that, it is common for unpaid bills to be referred to collections.20 Of the 23 people interviewed, 21 reported that at least some providers referred their debt to collections. Medical bills account for the majority of debts that are referred to third-party collection agents21 and for 17 percent of debts that are re-sold in the debt buying industry.22

Some bills may be referred to collections mistakenly. One study estimates that in 2010, 9.2 million Americans were contacted by a collections agency due to a billing mistake.23 Stuart was amazed at how quickly and automatically providers sent debts to collections. Though he had negotiated a payment plan with the hospital and had paid every installment on time, after 90 days the balance due was nonetheless referred to a collections agency. When he called the hospital to ask why, he was told it was an automatic practice and advised to ignore the collections notices and continue making payments directly to the hospital. Another bill that Stuart had paid in full was mistakenly sent to collections. It was up to Stuart to document the mistake in order to clear up this dispute.

For most we interviewed, being contacted by a debt collector was a new and unpleasant experience. A few people reported aggressive and harassing practices, such as late-night calls. Collections actions prompted many to take drastic steps to pay; sometimes these actions compounded their problems.

Credit card financing of medical debt

Most of those interviewed used credit cards to finance at least a portion of their medical debt. A 2007 study indicates that among low- and middle-income households with credit card debt, 29% report that medical expenses contribute to that debt. These so-called “medically indebted” individuals generally have much higher levels of credit card debt compared to consumers who have no medical bills on their credit card balances (“non-medically indebted.”) They are also twice as likely to have been called by bill collectors.

Charlene’s family became uninsured in 2009 when her husband lost his vision, job, and health benefits. The following year, their teenage daughter was hospitalized after an accident and in 2011, Charlene needed surgery. Hospital bills totaled $23,000. Though the hospital’s web site notes a charity care program, the only relief offered Charlene was a two-year payment plan with $800 monthly installments. When she said she couldn’t afford payments, the billing office urged her to pay with a credit card. She put several thousand dollars on the card, but then stopped when she saw how finance charges were adding to the total. Finally, Charlene took most of her retirement savings and emptied her daughter’s college fund to pay some of her debts.

Several others were encouraged to use special medical credit cards that can be used to pay bills for participating providers and that waive finance charges if bills are paid off within a specified period, such as 6-18 months.24 Other people elected to use credit cards on their own out of a sense of duty to pay providers who were caring for them. Still others relied on credit cards to finance day-to-day household expenses in order to free up cash to pay medical bills. In the end, however, most expressed regret over credit card financing because interest charges and late fees added significantly to what they owed.

Consequences of Medical Debt

Across the board, medical debt triggered other hardships and financial instability among every one of the individuals interviewed. Studies of the broader population also find that medical debt can have devastating consequences. People who have difficulty paying medical bills are more likely to forego needed care, for example, by cancelling routine doctor’s appointments, delaying recommended follow-up care, or failing to fill prescriptions.1 In addition, they are significantly more vulnerable to other financial hardship and are also more likely to deplete savings, borrow from relatives, suffer damaged credit, or file for bankruptcy.2

Through case studies, we observed people experienced severe consequences when medical bills became unmanageable:

Damaged credit

Virtually everyone interviewed had experienced substantial damage to their credit rating as a result of medical debt. Generally, when bills are referred for collections, this action can be reported to credit rating agencies. According to industry experts, “If you have an account go into collections and reported on your credit, your credit score will drop by a substantial amount.”3

Most of those interviewed had not experienced credit problems before the medical bills. Once damaged, though, they learned it can take years to restore one’s credit rating. With poor credit, people face difficulty qualifying for mortgages, auto loans, and other consumer credit, or faced higher interest rates. Bad credit can also complicate transactions with new employers, utility companies, insurers, even cell phone companies, who commonly run credit checks on applicants.4

|

Table 4. Description and Implications of Credit Rating Scores

|

||

|

FICO Score

|

Score Description

|

# Case studies*

|

|

850-740

|

Excellent

Insurance companies are more likely to give you absolutely the best deals, because you are less likely to commit fraud. Thanks to your amazing credit responsibility, you are attractive to prospective employers, too.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: 3.034%

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 3.321%

|

0

|

|

740-700

|

Good

The majority of credit cards (including those with rewards) are available to you. Rates will be very low or close to zero. Getting an insurance policy should be an easy task, too. Your monthly insurance premiums will be somewhat higher than for those with top scores, however, you should have no problems with getting an insurance policy for literally anything you want.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: 3.256%

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 4.754%

|

1

|

|

699-641

|

Average

This score is an absolute minimum to get a fair mortgage and auto loan terms. Insurance policies will be up by a significant amount for people in this range due to the potential risk for non-payment of premiums.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: 3.647%

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 6.795%

|

2

|

|

640-500

|

Bad

You represent a very high credit risk to the lenders and you won’t be able to get a mortgage at all (in most cases). You will be able to get an auto loan, but your interest rates will be around 15%. Insurance policy and car insurance will be very limited for you and cost significantly more than for those with good scores. Also, your choice of credit card is very limited if you fall in this range. However, if you still want a credit card, consider choosing a secured credit card.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: very hard or impossible

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 15.608%

|

14

|

|

500-300

|

Very Bad

Getting a mortgage with this score is almost impossible. You still may get an auto loan, but expect almost double interest rates. Many banks may not even let you open a checking account with this score. Unfortunately, most insurance companies will refuse to work with you, based on the risks you pose.

– Average Mortgage Interest Rates: very hard or impossible

– Average Auto Loan Interest Rates: 17% or impossible

|

6

|

|

Source: http://creditscoreranger.org/

* Case study credit scores reflect status at time they sought counseling from ClearPoint. Many clients experience further decline in scores before debt problems are resolved.

|

||

Emotional distress

Virtually everyone interviewed expressed feeling shame or embarrassment to be in medical debt. Most had not had any serious financial difficulties or debt problems before medical bills began. Most voiced a strong personal ethic to always pay their bills and were distressed to find themselves in debt. Sonya talked about how juggling bills made her feel “way outside my comfort zone.” She described being in debt as a “nightmare” and filing for bankruptcy was a blow to her pride. Retelling her experiences, she said, was like “opening up a wound.” One person ended up divorced at the end of her ordeal, and said the stress of medical debt was a contributing factor. Another couple stayed together, though debt problems strained their marriage for months.

Economic deprivation

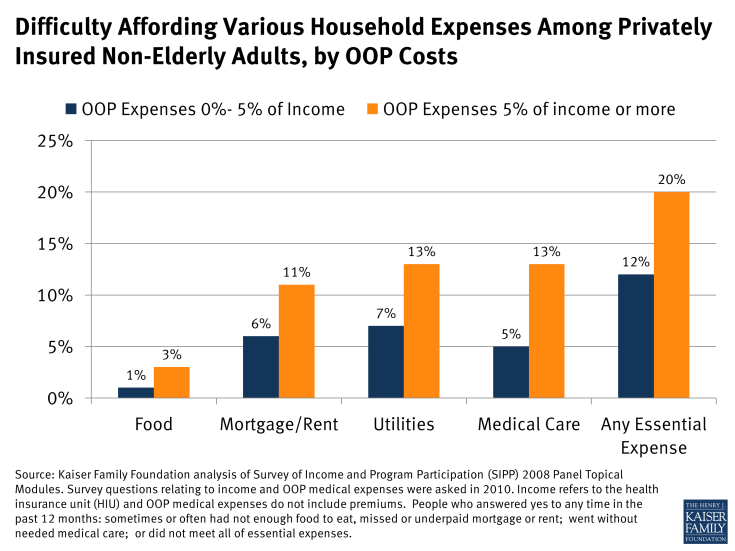

Our analysis of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) finds that privately insured people with out-of-pocket medical expenses that exceed five percent of their income are about twice as likely to have difficulties paying their rent and utilities, affording food, and to face barriers accessing medical care, compared to those with OOP costs less than five percent of their income.

Most people we interviewed drastically reined in household spending in the face of medical debt. They did without heating oil, groceries, even glasses for their children. A few sold their cars; others took on second part time jobs. Maisy noted, “I’m a pretty notorious penny pincher, and we haven’t bought anything that wasn’t from a thrift store in years, but those sorts of medical debts you just can’t penny-pinch your way out of.” Several people we interviewed were able to consolidate their bills through debt management programs (DMPs) that ClearPoint helped arrange. Stuart expects to pay off all the bills eventually – he’s been paying creditors $1,000 per month under his DMP for the past two years and has one more year to go. Duncan is also paying $1,000 under his DMP to clear up bills from his wife’s cancer treatment that date back to 2010. The DMP installment takes one-third of his take home pay, the mortgage takes another $1000, leaving the family of three just $1,000 per month for everything else. For some, austerity measures were temporary, for others it became their new way of life. As Dorothy put it, “once I thought I was headed toward being middle class, but not now.”

Figure 4: Difficulty Affording Various Household Expenses Among Privately Insured Non-Elderly Adults, by OOP Costs

Depleted long term assets

Eight people we interviewed severely depleted long term assets to pay medical bills. Gwen, 57, took $10,000 out of her 401(k) – one-fifth of the balance – to pay some of the medical bills she owes. She doesn’t expect to retire anytime soon. Charlene, 52, took $23,000 out of retirement savings – it had taken her 14 years to put away that amount – and also cashed out her daughter’s $5,000 college fund to pay medical bills. Stuart didn’t have to tap retirement savings, but, during the period when he incurred large medical bills, he had to reduce what he was paying toward his two sons’ college expenses by several hundred dollars per month. The boys made up the difference by taking out student loans. Kris took out a home equity line of credit to pay about $5,000 in medical bills. His medical bills are paid, but now his mortgage payment is much higher.

Medical bills often trigger such difficult decisions. According to one study, 11 percent of Americans have taken money out of retirement savings to pay medical bills. Described as a “retirement derailer,” such action can significantly delay retirement plans or lead to financial insecurity during retirement.5 Derailers can be particularly problematic for people over age 40, who won’t have as many years to make up for early withdrawals and lost contributions. Another study found that among medically indebted individuals, one fifth used retirement funds and nearly one-quarter withdrew equity from their homes to pay debts.6

Housing instability

Medical debt has also been shown to contribute to housing instability, including missed mortgage or rent payments, property tax liens, difficulty qualifying for loans, eviction, disruptive moves to less expensive housing, rental applications denied and in extreme circumstances, homelessness. According to one study, 27 percent of people with medical debt also experienced such housing-related problems.7

Several whom we interviewed found their homes threatened by medical bills. Some fell behind on rent or mortgage payments for a few months, then were able to get caught up; others never recovered and lost their homes. Gwen was determined to pay the $40,000 in her husband’s medical bills that insurance wouldn’t cover. When she asked her mortgage company if they would revise her loan and lower the monthly payment, she was told such programs were only for clients who were in arrears, so she skipped a few payments. The bank still refused to modify her loan, however, and a few months later started foreclosure proceedings. Gwen decided she would be better able to pay past debts, as well as new bills for her husband’s ongoing care, if she didn’t pay the mortgage so, as she put it, “I let them take the house.” A friend found a less expensive, smaller place that Gwen and George now rent. Connie and her family of four lost their home to foreclosure, as well. Her husband was injured in an auto accident and for several years she tried to juggle bills, including the mortgage, to keep pace with medical bills. The bank foreclosed in 2010, and Connie and her family moved back to Oklahoma to live in a relative’s home.

Bankruptcy

Medical bills are a leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the U.S., contributing to 62 percent of personal bankruptcies in 2007. Most who filed for medical bankruptcy that year were well educated, owned homes, and had middle-class occupations. Three quarters had health insurance.8

Of the 23 persons interviewed for this report, 15 had filed for bankruptcy. Most filed under Chapter 7 – meaning their debts were discharged. A few filed under Chapter 13, and so agreed to pay most or all of their unsecured debts over a period of time, typically three to five years, under a court-ordered payment plan. While these individuals expressed some relief at the protection afforded them; most did not want to resort to bankruptcy and many resisted filing as long as they could. Seven filed only after tapping retirement or college savings to pay medical bills or losing their home to foreclosure – assets that would have been protected under a bankruptcy filing. Two others either lost their home or borrowed against their home in lieu of filing for bankruptcy. And, though bankruptcy is considered a last-resort solution, nine of those who filed for bankruptcy have since incurred significant new medical bills and worry what will happen if they can’t pay those since they won’t be allowed to file for bankruptcy protection again for many years.

Difficulty accessing care

Finally, many studies have documented that that people with unaffordable medical bills also tend to experience difficulties accessing care.9 In some cases, providers may refuse to treat patients who cannot pay their bills. Kieran, for example, reported that one hospital to which he owed money refused to pre-register his wife for a hospitalization until overdue bills were paid. More often, people we interviewed decided to forego care in order to avoid incurring even more bills they could not afford. Dillon, for example, put off needed dental care because he already was struggling to pay thousands of dollars in medical debts to other providers. Jeanne, a cancer survivor, delayed recommended follow up visits until she could assemble the cash to pay for them.

Discussion

People rely on health insurance to protect against catastrophic medical expenses. When insurance protection falls short, medical debt can result. The high prevalence of medical debt is an indication that health insurance does not always shield people from an unaffordable level of expenses. Most insured people have cost-sharing liability that puts them at risk for medical debt. The median household income in the U.S. in 2012 was $51,017.1 When medical bills exceed five percent of income (roughly $2,500 or less for most households), people are twice as likely to have trouble making ends meet. Cost-sharing liability under most private health insurance plans today exceeds this level. Most Americans don’t have sufficient cash on hand to pay bills of this level and are just one hospitalization away from the bill collector.

The Affordable Care Act will bring about significant improvements in the health coverage system that may prevent or lessen some of the medical debt problems experienced by our interviewees and others:

Subsidies and Market Reforms for Non-group Coverage – The ACA changes market rules for non-group coverage, prohibiting insurers from turning people down or charging them more based on health status. The ACA also limits premium age adjustments to 3:1. And, importantly, under the ACA, sliding scale tax credit subsidies will be available to individuals with incomes between 100% and 400% of FPL. For people who buy non-group coverage today, on average, tax credit subsidies will finance about one-third of the premium.2 As a result, people like Morgan won’t be stranded in policies whose premiums spiral once they get sick and can no longer pass medical underwriting. In addition, under the ACA, Morgan (whose income is only about 220% of the FPL for a family of four) and his family will be eligible for both premium and cost-sharing subsidies. His premium contribution will likely be less than $300 per month for a family policy – one-quarter of what he had been paying. At this income level, Morgan would also qualify for modest cost-sharing subsidies, which will be offered to people with incomes between 100% and 250% FPL.3

Cost-Sharing Limits under Private Health Plans – Starting in 2014, the ACA requires that a $6,350 annual limit per person will apply to all types of cost-sharing for in-network care under all non-grandfathered private health plans – both group and non-group. This change could prove beneficial to people like Gwen and Richard whose deductibles and copays did not count toward their annual OOP limits.

End of Annual Dollar Limits – Starting in 2014, the ACA requires that all health plans remove annual dollar limits on covered benefits. As a result, people like Safiya will not encounter dollar limits under so-called “mini-med” policies that leave them effectively uninsured when coverage runs out.

Essential Health Benefit Standards – Starting in 2014, health insurance policies sold in the small group and non-group markets must cover ten categories of essential health benefits (EHB) – including hospitalization, ambulatory care, rehabilitative and habilitative services, mental health care, and prescription drugs. Mental health parity rules will apply to these and large group health plans as well, so higher cost-sharing or stricter visit limits will not be permitted for these services and exclusions based on self-inflicted injury, as happened to Maisy’s husband, will not be allowed.

Consumer Assistance – Under the ACA, Consumer Assistance Programs (CAP) can be established in states to help all residents – regardless of the source of coverage – answer questions, resolve disputes and appeal claims denials. In the first year of operation, 35 state programs were established. In that year CAPs provided assistance to more than 200,000 consumers, and helped more than 25,000 consumers appeal insurer denials and recover $18 million in reimbursements.4

>

These changes notwithstanding, the ACA will not address all of the underlying causes of medical debt. For example:

High Cost-Sharing will Persist under Many Plans – The ACA establishes an affordability standard for health insurance premiums, but not for out-of-pocket medical expenses.5 Even with limits on cost-sharing established under the ACA, deductibles and other cost-sharing will continue at a level above what many people could afford if a significant illness or injury strikes. In the Exchanges, people with incomes between 250% and 400% FPL will likely face deductibles of up to $2,000 or more in silver plans – much higher levels under bronze plans – and OOP limits of $6,350, so would be at risk for having cost-sharing expenses in excess of 10 percent of gross income. People will have the option of enrolling in Gold plans with lower cost-sharing, but with higher premiums.

Some people in large group plans may face cost-sharing in excess of $6,350 next year. The federal government announced it will delay enforcement of the maximum OOP limit for group health plans until 2015. As a result next year, group health plans may require people to satisfy more than one $6,350 OOP limit if the plan uses multiple claims administrators – for example, a pharmacy benefit manager that just administers the prescription drug benefit, separate from other covered medical benefits.6

Limited Protections for Out-of-Network Care – When patients do receive non-emergency care out-of-network, the ACA does not limit the cost-sharing that plans can apply. Nor does the ACA limit balance billing that non-network providers can charge. When people inadvertently receive out-of-network care, such as from an anesthesiologist who doesn’t participate in the same plan network as the hospital and surgeon, some health plans voluntarily undertake measures to limit the consumer’s cost exposure – by covering the non-network service at the in-network level, and/or by basing reimbursement levels on the provider’s billed charge to limit balance billing. The ACA does not require plans to adopt such measures, however.

The ACA does require all health plans to cover emergency services as though they were provided in network, even when patients can’t get to an in-network facility for such care. The ACA also requires health plans to offer an adequate provider network. Another provision of the ACA gives the Secretary authority to require plans to report data on out-of-network cost-sharing so this requirement can be monitored. This data reporting provision has not yet been implemented.

Limits on Essential Health Benefit Standards – The ACA requirement to cover essential health benefits applies only to non-group health plans and fully-insured small group health plans. As a result, Dillon’s large group health plan may continue to not cover the physical therapy that he needs. In plans that are subject to the EHB, federal standards do not precisely define EHB services and leave some flexibility for insurers to substitute services within categories. As a result, for example, autism treatments like those that Sonya’s child received might continue to be uncovered under qualified health plans in many states. In addition, federal standards rely on existing “benchmark” plans that may, today, include non-dollar limits on covered services. Many state benchmark plans, for example, limit the number of covered inpatient days or outpatient visits for rehabilitative care, such as the extended physical therapy that Richard needed. Such benefit limits can continue after 2014.

Lack of Resources for Consumer Assistance – Consumer assistance programs authorized under the ACA have struggled with limited resources. The law authorizes “such sums as may be necessary” to support CAPs, but only appropriated $30 million. The last funding opportunity for CAPs took place in 2012, and no further funding has been announced since then. CAPs are the only entities required, by federal law, to help privately insured people resolve health plan complaints and claims disputes and file appeals. Absent this help, as case studies illustrate, some people may continue to be overwhelmed by insurance paperwork they cannot understand and even incur debt for bills insurance should have paid.

The ACA will provide health insurance to millions of Americans who are currently uninsured, which may also improve access to health care and lower their out-of-pocket expenses and exposure to medical debt. People who are insured will also see improvements in the protection that health coverage offers. However, in light of the limited assets many people have, the problem of medical debt is likely to persist and lead to continued debate over the tradeoffs inherent in providing more comprehensive coverage and limiting federal costs for premium and cost-sharing subsidies.

Appendices

Appendix

Summary of Medical Debt Case Studies

Ben, 59, Trucker

Income: $68,000 (590% FPL)

Medical bills: $5,000

Bills incurred by: Self

Timing of bills: 2012 (2nd time in medical debt)

Insurance status during bills: Employer Sponsored Insurance (ESI)

Ben has good health insurance through his job with a trucking firm. The policy has a $250 deductible, with 20% coinsurance to an OOP limit of $3,000 annually per person. He and his wife are covered under the plan. She takes medications and requires regular physician visits for a chronic condition. He has diabetes and suffers chronic back pain following a fall. Last year he needed surgery, with a brief readmission following a complication. His share of expenses came to more than $5,000 – mostly from in-network cost-sharing, but a significant amount of balance billing.

Ben was surprised at the “truckload” of bills, not only from the hospital and surgeon, but anesthesiologist, radiologist, labs, imaging facilities, and other providers, many of whom he did not select and were not in his plan’s network. “I found out one thing. Anesthesiologists aren’t with anyone’s network. That was a surprising thing to me. I only learned this after the bills came.” Ben’s share of the anesthesia bill alone came to $900. This was Ben’s second bout with medical debt. Ten years ago, his wife was seriously ill and needed surgery. Bills from that event were much higher, eventually causing the couple to file for bankruptcy.

Charlene, 51, Teller

Income: $38,000 (195% FPL)

Medical bills: $23,000

Bills incurred by: Self and daughter

Timing of bills: 2010-2011

Insurance status during bills: Uninsured

Charlene, her husband Craig, and their teenage daughter had health insurance until 2009, when Craig lost his sight, job, and health benefits. Before they lost coverage, the family had accumulated about $8,000 in unpaid medical bills from Craig’s treatments, mostly due to cost-sharing. Then after losing coverage, Charlene’s daughter was hospitalized in 2010 after an accident, and Charlene needed surgery in 2011.

The hospital bills, alone, totaled $23,000. Though the hospital web site notes a charity care program, the only relief offered to Charlene was a payment plan with monthly installments of $800, which she could not afford. The billing office recommended she take out a loan or use credit cards. Charlene charged about $5,000 in bills to a credit card, and then stopped when she realized how finance charges increased the debt.

The debt was turned over to collections; Charlene described the calls as harassing, often early morning or late at night. She took $20,000 out of retirement savings to pay some of the bills, as well as living expenses – it had taken her 14 years to save that much – and also cashed in her daughter’s college savings of $5,000. With more bills to pay, she finally filed for bankruptcy, and all remaining debts were discharged in 2012. Charlene has a new job with health insurance and her daughter is in college on a scholarship. For now the family feels okay.

Dorothy, 59, Teacher

Income: $34,000 (300% FPL)

Medical bills: $4,500

Bills incurred by: Self

Timing of bills: 2011-12, and ongoing

Insurance status during bills: ESI

Dorothy has worked for the public schools for 20 years and has been covered under her job-based plan. Her premium contribution of $190 is deducted from her monthly paycheck. Originally, she was offered an HMO plan with very comprehensive coverage; in 2000, she was diagnosed with cancer and recalls paying almost nothing out-of-pocket for her care. Since then, the school district changed to a PPO plan with a $2,000 deductible with 20% coinsurance to an OOP limit and tiered copays for prescription drugs that range from $17 to $100 for the drugs Dorothy takes for several chronic conditions. Her monthly drug copays come to $150 each month and on her income and crowd out other expenses. She needs to replace her furnace but can’t afford it, so uses a space heater during the winter instead. She used to work a second part time job at a department store, earning an additional $600-700 per month, but had to quit when her condition worsened.

In 2011 she was hospitalized for a few days with an infection. Her share of the bills came to $4,500 of which she still owes $3,000. The hospital offered a $250 monthly payment plan, which Dorothy couldn’t afford, then reduced the monthly payment to $50. Dorothy also owes money to the doctors who treated her while in the hospital. She was surprised to receive so many doctor bills from that brief stay. Initially she tried to pay them with credit cards, but realized this just increased what she owed. The doctors turned unpaid bills over to collections. Dorothy says those calls (though polite) are overwhelming, as are the bills. She’s determined to pay and avoid bankruptcy at all costs, but the best she can do is “stack up the bills and just pay what I can when I can.”

Recently Dorothy went for her annual mammogram; the deductible applied so she owes another $208 for that. She wasn’t aware that preventive mammograms are supposed to be covered 100% or that she could appeal the plan’s decision to apply the deductible. She did not know her state has a Consumer Assistance Program that would help her file an appeal.

Dorothy is stunned to be in this position, even though she works full time and has health insurance. She assumed her coverage would keep care affordable. Now she’s worried to owe so much in medical bills that she just can’t afford to pay. “Once I thought I was headed toward being middle class,” she said, but not now. She gets up at 5:00 each morning to get to school by 7:00 and most days works another three hours after the kids are dismissed to prepare for the following day. She said that’s just what’s expected of teachers, and she doesn’t really mind, but notes “when I call the bank or the hospital and tell them I’m a teacher, I still have to pay just like anybody else.”

Gwen, 57, Medical Transcriptionist

Income: $22,000 (140% FPL)

Medical bills: $40,000

Bills incurred by: Husband

Timing of bills: 2011

Insurance status during bills: ESI

Gwen and her husband, George (64) have health coverage through her full time job. It’s a high cost-sharing plan with a $3,000 deductible per person, then 30% coinsurance to an annual OOP limit of $10,000, not including the deductible. For out-of-network coverage the deductible and OOP limit are twice as high. Their plan year begins in June. George suffers from diabetes and other chronic conditions, and was laid off a few years ago. In May 2011, he had a cardiac emergency requiring surgery. He lost eligibility for his unemployment benefits while sick because he was no longer actively working.

Because his hospitalization occurred at the end of the plan year, he had to satisfy two in-network deductibles and one in-network OOP within just a few months. In addition, there were extensive non-network claims from hospital based physicians, none of whom George chose. Even worse, George received poor care in an in-network rehab facility following his initial surgery. Complications led to re-hospitalization and second surgery. Following that his doctor recommended rehab within the hospital. The rehab unit was independently owned and not in plan network, but Gwen agreed because George was too fragile to move. George’s share of the cost of his 3-week stay was $23,000. By August 2011, they owed $40,000 in medical bills. Interestingly, almost no balance billing charges arose from the nonparticipating providers. Most were party to a “MultiPlan agreement” with an independently established fee schedule. Gwen’s insurance paid based on that fee schedule amount and providers agreed to not bill in excess of that amount.

Another ambulance claim for $1,000 was denied. Gwen wasn’t sure why; an earlier ambulance claim had been covered. The “explanation of benefits” did not provide a clear reason, though an earlier ambulance claim had been covered. It did not occur to Gwen to appeal the denial or out-of-network charges, and in any case, she doesn’t know where she would have found the time. As the sole breadwinner, she must continue to work full time to maintain income and insurance, plus she must care for her sick husband.

Gwen said as the bills streamed in, she just “set them aside” because she had no money to pay them. The nonprofit hospital offered to cut what they owed by 40% as part of the charity care program, but other providers, including the independent rehab unit within the hospital, just turned them over to collections. Gwen took $10k out of retirement to pay some of the bills. Without George’s income, she also fell behind on the mortgage. The bank would not agree to modify the loan, and Gwen needed to keep up with George’s ongoing care needs as well as basics like groceries, so “I let them take the house.”

Once the house went into foreclosure, Gwen was able to pay down more of the medical debt, though she still owes about $9,000. Fortunately a friend helped them find a less expensive house to rent. This year George turns 65 and will enroll in Medicare, further reducing the couple’s insurance premiums and cost-sharing expenses.

Kieran, 43, Car Dealer

Income: $75,000 (240% FPL)

Medical bills: $20,000

Bills incurred by: Spouse, children

Timing of bills: 2007-2011

Insurance status during bills: ESI