Medicaid’s Role in Financing Behavioral Health Services for Low-Income Individuals

Issue Brief

Behavioral health conditions affect a substantial number of people in the U.S. and are especially common among people with low incomes.1 ,2 ,3 Behavioral health conditions include mental illnesses, such as anxiety disorders, major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as substance use disorders (SUD), such as opioid addiction. These conditions range in severity, with some being more disabling than others. People with behavioral health needs may require a range of services, from outpatient counseling or prescription drugs to inpatient treatment.

As a major source of insurance coverage for low-income Americans, and as the only source of funding for some specialized behavioral health services, Medicaid plays a key role in covering and financing behavioral health care. In 2015, Medicaid covered 21% of adults with mental illness, 26% of adults with serious mental illness (SMI), and 17% of adults with SUD.4 In comparison, Medicaid covered 14% of the general adult population.5 In total, approximately 9.1 million adults with Medicaid had a mental illness and over 3 million had an SUD in 2015. Nearly 1.8 million of these adults had both a mental illness and an SUD.6 ,7

Current Medicaid program financing guarantees federal financial support to states with no pre-set limit. The Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), as proposed by the Senate, restructures federal Medicaid financing by changing it to a per capita cap or block grant, which would likely impact states’ ability to provide coverage for and access to behavioral health services for people who need them. This issue brief provides an overview of Medicaid’s role for people with behavioral health needs, including eligibility, benefits, service delivery, access to care, spending, and the potential implications of the BCRA.

How do people with behavioral health needs qualify for Medicaid?

Many people with behavioral health needs are eligible for Medicaid, although there is no single pathway dedicated to covering them. Most beneficiaries with behavioral health conditions qualify for Medicaid because of their low incomes. For example, adults may be eligible for Medicaid if they live in a state that expanded its program under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and have incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($12,060/year for an individual). In states that did not expand their programs, coverage for non-disabled individuals is typically limited to parents, pregnant women, and children. In non-expansion states, the median income eligibility level for parents is 44% FPL in 2017, but eligibility for children and pregnant women is higher. As of 2017, most states provide Medicaid or CHIP to children (49 states) and pregnant women (34 states) at or above 200% FPL.8 In total, over one in five (21%) adults and one in 10 (11%) children eligible for Medicaid based on income have a behavioral health diagnosis as of 2011.9

People with behavioral health needs, especially those with serious mental illness, may also qualify for Medicaid based on having a disability. In most states, individuals who have a mental illness that makes them eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), the federal cash assistance program for low-income aged, blind, or disabled individuals, are automatically eligible for Medicaid.10 ,11 To be eligible for SSI, individuals must have low incomes, limited assets, and an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level as a result of old age or significant disability. However, SUD is not considered a disability for purposes of qualifying for SSI.

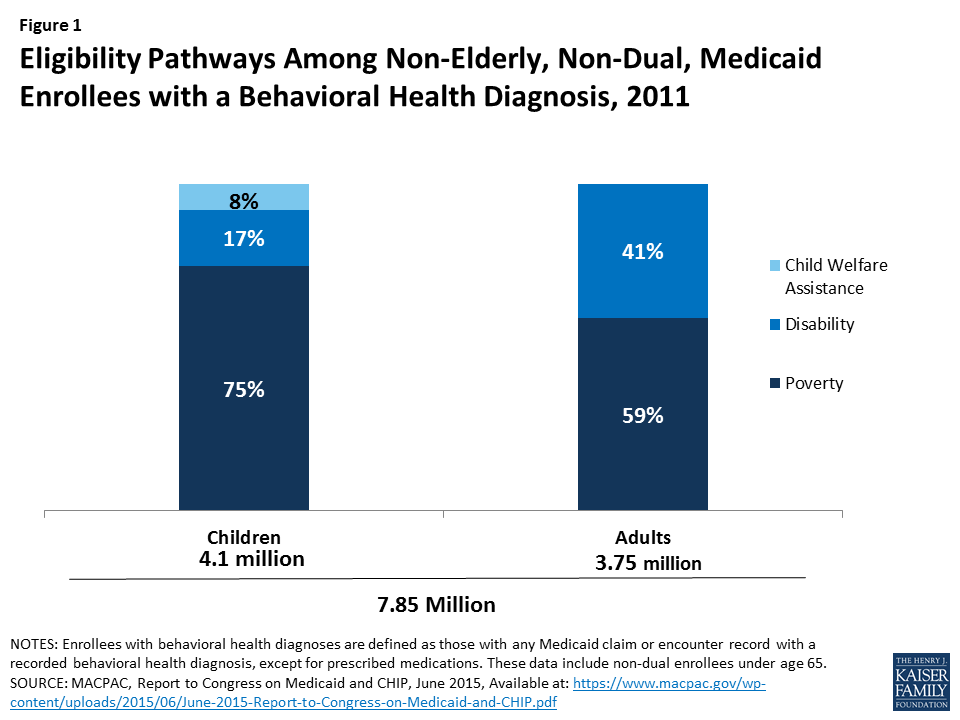

Fifty percent of adults and 47% of children eligible for Medicaid based on having a disability have a behavioral health diagnosis as of 2011.12 Additionally, among Medicaid beneficiaries with behavioral health conditions (excluding those who also qualify for Medicare), over four in 10 adults (41%) and one in six children (17%) are eligible for Medicaid based on having a disability (Figure 1).13

States can choose to offer other disability-related Medicaid eligibility pathways to people whose incomes exceed the SSI limit.14 For example, in 21 states, people with disabilities may be eligible for Medicaid up to 100% FPL, as of 2015.15 In 44 states, working individuals with disabilities whose incomes and/or assets exceed the limits for other pathways, may “buy-in” to Medicaid coverage. Over 400,000 people have been able to obtain coverage through the buy-in option as of 2015.16

In addition, children who are eligible for Medicaid because of their involvement with the foster care system may have behavioral health needs. Among children with Medicaid/CHIP who had behavioral health conditions in 2011, nearly one in ten (8%) entered the program through the child welfare assistance pathway (Figure 1).17

What behavioral health services does Medicaid cover?

People with behavioral health conditions may require a broad range of medical and long-term care services. These include outpatient services, such as individual therapy, group therapy, partial hospitalization, and case management; inpatient services, such as detoxification, hospital visits, and residential treatment; medications as part of psychiatric treatment for mental illness or medication-assisted treatment for SUD; and home and community-based services, such as supportive housing and supported employment.

Behavioral health services are not a specifically defined category of Medicaid benefits, but the program covers many behavioral health benefits. Some behavioral health benefits fall under mandatory Medicaid benefit categories that all states must cover by federal law. For example, psychiatrist services may be covered under the “physician services” category, and inpatient psychiatric treatment for individuals under age 21 or over age 65 may be covered under the “inpatient hospital services” category.18 Historically, federal law has prohibited federal Medicaid payments for services provided in “institutions for mental disease” (IMD) (generally defined as having more than 16 beds) to adults age 21-64. However, in April 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued final Medicaid managed care regulations that allow states to receive federal matching funds for managed care capitation payments for adults age 21-64 who receive psychiatric or SUD inpatient or residential services in an IMD for up to 15 days in a month as of 2016. States are able to receive these funds under the authority for health plans to cover services “in lieu of” those available under the Medicaid state plan.19 In addition, in July 2015, CMS provided guidance stating that states could request federal funding for services delivered to nonelderly adults residing in IMDs through Section 1115 demonstration waivers in order to be able to provide a full continuum of care.20

States also cover behavioral health benefits through optional benefit categories that they may choose to include in their Medicaid programs, such as case management services and prescription drugs. One important benefit category for behavioral health is rehabilitative services option, through which states commonly cover non-clinical behavioral health services such as peer support and community residential services.21 In addition, under waiver or state plan authority, states can provide home and community-based long-term care behavioral health services that support independent community living, such as day treatment, and psychosocial rehabilitation services.22 For examples of the types of behavioral health services covered by Medicaid, see Bill and Eric’s stories below.

Medicaid covers services that enable people with disabilities to work. In addition to providing personal care and transportation services that help people with disabilities get ready for the day and get to work, states also can cover supported employment services, such as job coaching, to help people with behavioral health conditions obtain and maintain employment.

Under the ACA Medicaid expansion, states must offer a set of benefits for those newly eligible for Medicaid, known as alternative benefit plans (ABP), and they may choose to offer ABPs to most other Medicaid adults.23 While the traditional Medicaid state plan benefit package does not include a minimum set of federal behavioral health benefits, ABPs must cover the ACA’s ten essential health benefits (EHB), which include both mental health and SUD benefits.24

Like most other insurers, Medicaid ABPs and MCOs that cover behavioral health services must do so at parity, or to the same extent and on the same terms that they cover physical health services.25 ,26 States are encouraged, but not required, to apply the parity rules to their traditional (non-ABP) Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) programs as well.

Medicaid coverage of behavioral health services is sometimes more comprehensive than private insurance coverage. While many insurance plans cover psychiatric hospital visits, in some states, Medicaid is more likely than many private insurance plans to cover additional services, such as case management, individual and group therapy, detoxification, and medication management, in addition to psychiatric hospital visits.27

Behavioral health services for children are particularly comprehensive due to Medicaid’s Early, Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit for children. EPSDT includes all medically necessary Medicaid services permitted under federal law and is required for children from birth to age 21. Under this benefit, states must provide access to behavioral health care, including screenings and assessments. Children diagnosed with behavioral health conditions receive any service available under federal Medicaid law necessary to correct or ameliorate the condition, even if the state does not cover the service for adults.28 ,29

How are behavioral health services delivered to Medicaid enrollees?

States use a combination of fee-for-service and managed care arrangements to deliver behavioral health care to Medicaid beneficiaries. Historically, Medicaid paid for services, including those for behavioral health conditions, on a FFS basis, through which providers are paid for each billable service they deliver. During the past several decades, Medicaid payment has shifted to managed care arrangements, through which providers are paid for some or all services at a prepaid rate. Behavioral health services are increasingly provided through managed care arrangements, but some states “carve out” behavioral health services from their managed care contracts, and these services are instead provided and financed under another contractual arrangement, such as a prepaid health plan, or on a FFS basis.30 However, many of these states are moving to “carve in” these services and deliver them through the same managed care contracts as physical health services.31 For example, in 2016, 20 states covered outpatient mental health services, 24 covered inpatient mental health services, and 24 covered SUD services through comprehensive managed care contracts.32

States and health plans have undertaken a range of reforms to delivering behavioral health services to Medicaid beneficiaries. Many state Medicaid agencies, health plans, and providers are implementing physical and behavioral health integration strategies in Medicaid to address longstanding fragmentation between these services.33 These strategies include universal screening for behavioral health conditions during medical appointments and vice versa, using patient navigators, co-locating services at a single site, sharing data and information, blending funding streams, and incentivizing providers to work together to coordinate care.34 ,35

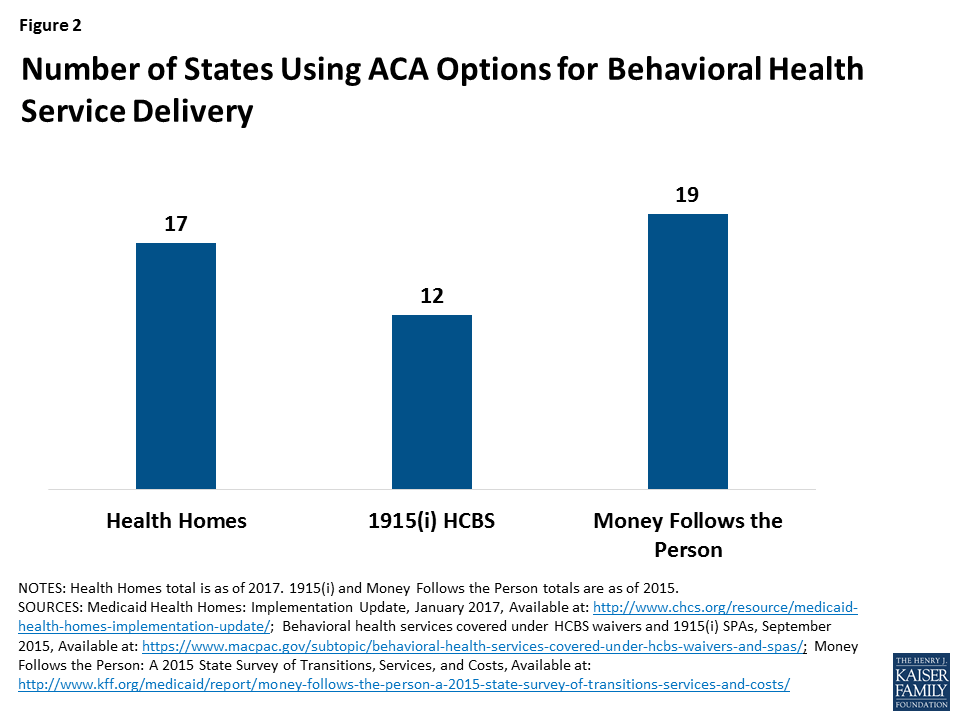

States are also using the health homes plan option, created under the ACA, to deliver care to beneficiaries with chronic physical or mental health conditions. Under this model, states cover care management and coordination services designed to integrate physical and behavioral health services, acute care and long-term services and supports, and referrals to community-based social services and supports. Of the 21 states that had implemented health homes as of January 2017, 17 included beneficiaries with behavioral health conditions, primarily serious mental illness (Figure 2).36

The ACA also expanded the Section 1915 (i) home and community-based services (HCBS) state plan option, which allows states to offer HCBS to beneficiaries who have some functional needs but who do not yet require an institutional level of care.37 This option enables states to provide HCBS as a preventive measure to avoid the need for more costly care in the future, such as institutional care, if beneficiaries’ conditions were to worsen without services.38 Under Section 1915 (i), states can target services to specific populations, including people with behavioral health needs. Twelve states have opted to operate Section 1915 (i) programs targeting people with behavioral health conditions as of 2015 (Figure 2).39

In addition, the Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration provided states with enhanced federal funding for 12 months for every beneficiary who transitioned from an institution to the community. Of the 44 states participating in the MFP demonstration, 19 focused on increasing the number of transitions for people with mental illness (Figure 2). These states used a number of strategies, such as conducting outreach at nursing facilities, working with MCOs to coordinate services, and adding new demonstration services such as SUD treatment and peer support. As a result of this program, there was a 77 percent increase in transitions for individuals with mental illness from 2013 to 2015.40 Although states can continue to spend their existing grant money until 2020, MFP funding expired in September 2016, and has not been reauthorized by Congress.

Are Medicaid enrollees able to access behavioral health care?

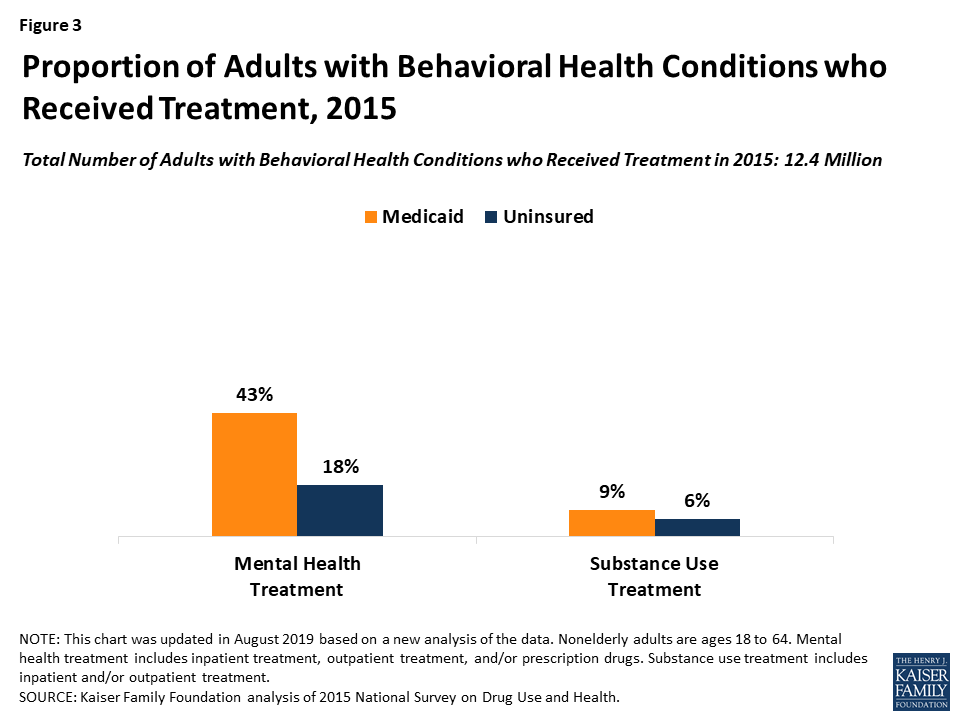

Compared to people who are uninsured, individuals who are covered by Medicaid have better access to behavioral health services. Among adults with behavioral health conditions in 2015, those with Medicaid were more likely than those without coverage to receive mental health treatment (43 percent versus 18 percent) and SUD treatment (9 percent versus 6 percent) (Figure 3).41 Research has also demonstrated that adults with Medicaid who had mental health conditions were significantly less likely than those who were uninsured to report unmet need for health care.42 Additionally, increased availability of Medicaid coverage has been associated with a decreased likelihood of having an unmet need for behavioral health care43 and an improvement in mental health status.44 One study found that, among adults with mental illness, those with Medicaid were over two and a half times as likely as those without insurance to have received treatment in the previous year, even after accounting for demographic differences between the two groups.45

However, some gaps remain in access to behavioral health care for many people, including those with Medicaid. In 2015, approximately 2.5 million people with Medicaid reported an unmet need for mental health treatment.46 Some of the barriers to accessing behavioral health treatment in Medicaid reflect larger system-wide access problems. Many individuals with behavioral health conditions, with and without Medicaid, report not receiving treatment for their conditions. The overall shortage of behavioral health providers in the United States,47 and the relatively small number of psychiatrists who accept insurance,48 both present barriers to accessing behavioral health care. Additional barriers may exist for individuals with SUD because SUD coverage has traditionally been even more limited than that of mental health in both private insurance and Medicaid.49 Social stigma associated with mental illness and SUD as well as individuals’ perception that they do not need treatment may also pose barriers to accessing care.50 ,51

How much does Medicaid spend on behavioral health services?

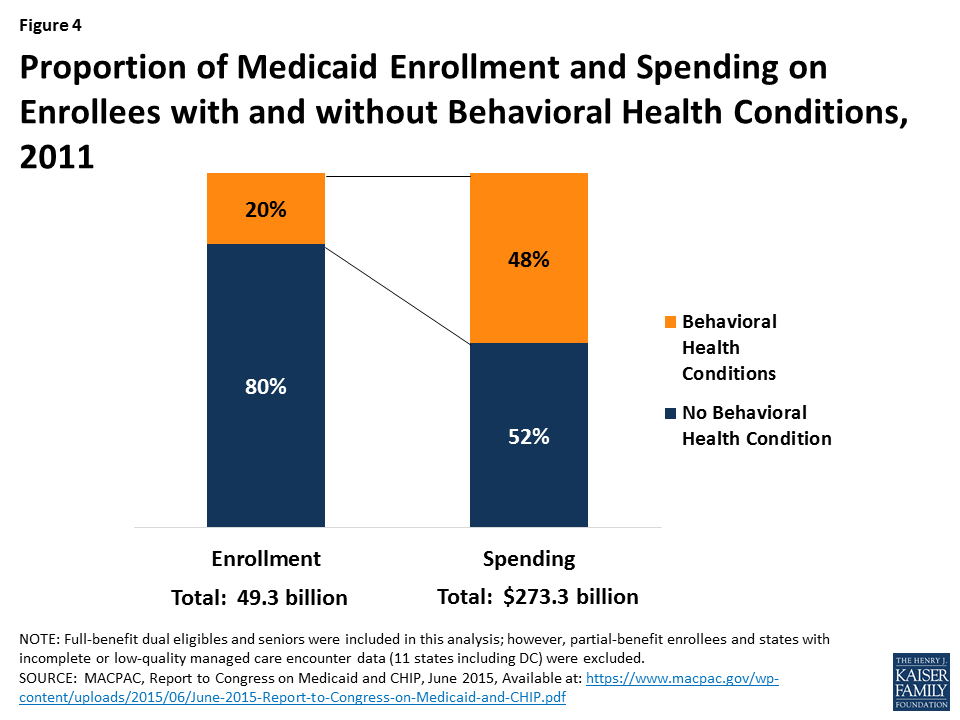

Medicaid expenditures for enrollees with behavioral health conditions are relatively high due to this group’s substantial health needs. Compared to enrollees without behavioral health conditions, Medicaid beneficiaries with these needs are more likely to have comorbid chronic physical conditions and to rate their overall health as fair or poor.52 As a result, they have more intensive service use than other beneficiaries, including office visits, inpatient stays, emergency visits, and prescription drugs.53 Though enrollees with behavioral health conditions accounted for just 20 percent of enrollees in 2011, this population accounted for almost half (48%) of Medicaid spending (Figure 4).

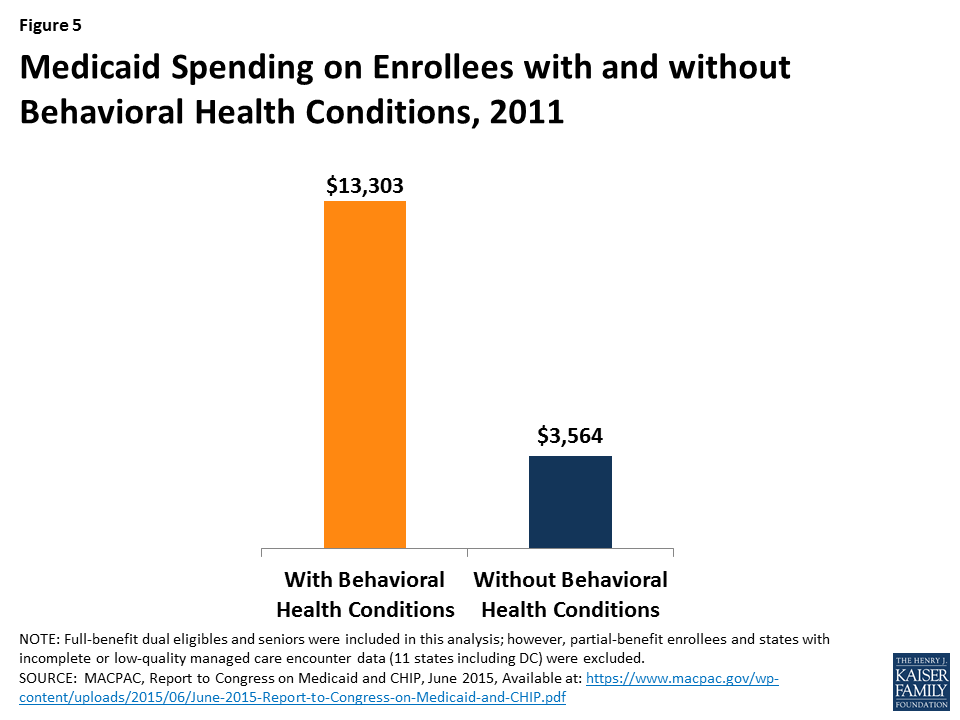

On a per enrollee basis, average Medicaid spending for people with behavioral health diagnoses was nearly four times what it was for enrollees without these diagnoses ($13,303 vs. $3,564). (Figure 5). This includes both behavioral and physical health care as well as long-term care, reflecting enrollees’ greater needs in a variety of areas.54 ,55

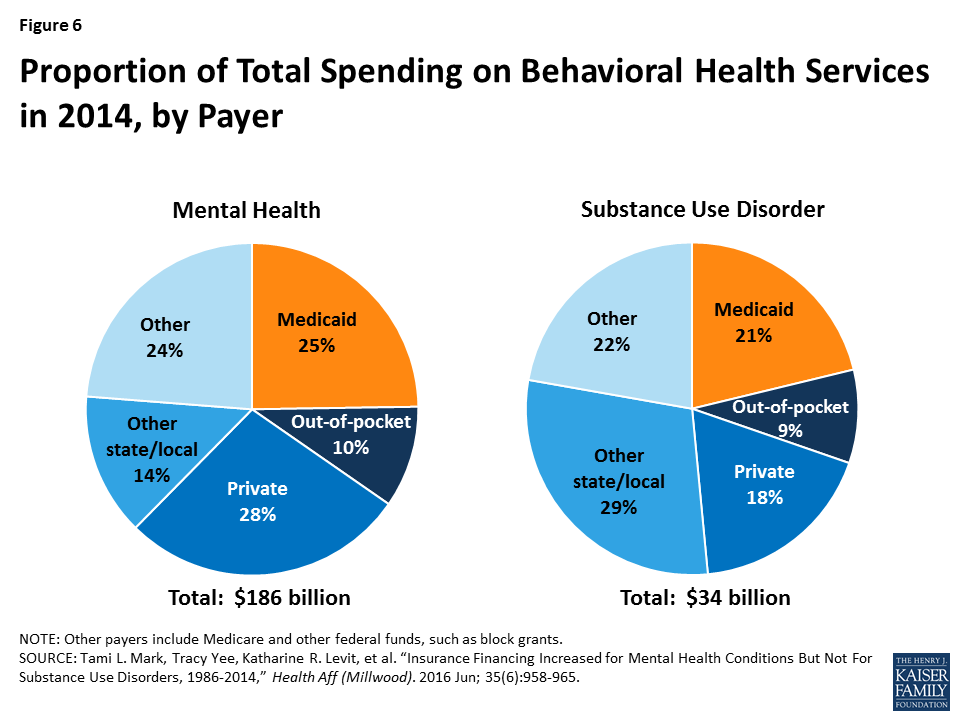

Medicaid accounted for 25% of all spending on mental health services and 21% of all spending on SUD services in 2014, making it one of the largest financing sources (Figure 6). Private insurance accounted for 28% of mental health spending and 18% of SUD spending, and state and local funds accounted for 14% and 29%, respectively.56

Medicaid spending on behavioral health grew substantially following the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. In 2014, spending on mental health was approximately $46.5 billion, a 23% increase from 2009. During the same period, spending on SUD increased 43%, totaling $7.1 billion in 2014.57 Many adults who gained coverage under the ACA’s expansion were previously uninsured and, through Medicaid, they were able to access treatment for behavioral health needs.

States are able to use Medicaid as a platform to support changing patterns of care for behavioral health over time. For example, Medicaid has supported the shift from institutional to community-based care, the adoption of new psychotropic drugs, and the use of assertive community treatment (ACT) and other rehabilitative programs. Medicaid financing has also enabled states to provide a full continuum of care, including prevention, screening, evidence-based treatment, and recovery support. As a result, Medicaid is now a crucial component of state behavioral health systems.

Looking Ahead

Individuals with behavioral health conditions often require costly medical and long-term services. As a result, although they make up only 20% of the Medicaid population, they account for 48% of Medicaid spending. Medicaid facilitates access to a broad range of mandatory and optional behavioral health services, including psychiatric care, counseling, prescription medications, inpatient treatment, case management, and supportive housing. The ACA has played an important role in increasing access to behavioral services among Medicaid enrollees by expanding eligibility. Many states have also taken advantage of newer HCBS service delivery options in recent years, which have enabled beneficiaries with behavioral health conditions to live in the community while they receive care. States also are exploring new models to better integrate physical and behavioral health care.

Medicaid’s financing structure currently guarantees federal financial support to states with no pre-set limit and allows federal spending to increase as state spending increases. The BCRA would fundamentally change the Medicaid program’s federal financing structure and substantially decrease the amount federal funds available to states through a per capita cap or block grant, which has implications for enrollees with behavioral health conditions. The BCRA would also eliminate the enhanced federal financing for the ACA’s expansion, which could lead expansion adults to lose coverage. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the BCRA would result in 15 million fewer Medicaid enrollees and a $772 billion reduction in federal Medicaid spending from 2017 to 2016 as a result of the elimination of the enhanced federal funding for the ACA’s expansion and the creation of a per capita cap or block grant.58

In response to the BCRA’s changes, states may restrict Medicaid eligibility and may be incentivized to limit coverage for enrollees with behavioral health conditions, who are especially costly. States may also trim benefit packages and remove optional services that are particularly valuable to enrollees with behavioral health conditions. In addition, states may decrease provider payment rates, which may lead to decreased provider participation in Medicaid and further limit access to behavioral health services. Finally, states currently benefit from the guarantee of federal Medicaid financing with no pre-set limit, which allows them to respond to emerging issues, such as the opioid epidemic. Faced with increased pressure to limit costs, states will likely struggle to address these issues. States with certain risk factors, such as a high share of the population reporting poor mental health and a high opioid death rate, may be especially challenged to respond to federal Medicaid cuts and caps.

Decreases in eligibility, coverage, provider payment rates, and, ultimately, access could result in high levels of unmet need for behavioral health services among Medicaid enrollees. In addition to impacting health outcomes, untreated behavioral health conditions are associated with many societal costs, resulting from increased emergency department utilization, criminal justice involvement, and loss of productivity.59 ,60 ,61 ,62

Individuals with behavioral health conditions have a unique and complex set of needs, and Medicaid plays a large role in facilitating access to necessary treatment. As the debate about fundamentally restructuring Medicaid program financing continues, the unique needs of these enrollees warrant consideration.

Endnotes

- Committee to Evaluate the Supplemental Security Income Disability Program for Children with Mental Disorders; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children, ed. Boat TF and Wu JT, (Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); October 2015), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26632628. ↩︎

- Jitender Sareen, et al., “Relationship Between Household Income and Mental Disorders: Findings From a Population-Based Longitudinal Study,” Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 4(2011):419-27. ↩︎

- Bridget F. Grant, et al., “Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III,” JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 8(2015):757-66. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. ↩︎

- [v] Ibid. ↩︎

- [vi] Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, September 2016), https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ↩︎

- Tricia Brooks et al., Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2017: Findings from a 50-State Survey (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2017-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: MACPAC, June 2015), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/June-2015-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf. ↩︎

- [x] States that elect the § 209 (b) option are permitted to use definitions of disability or financial eligibility standards that are more restrictive than the federal SSI rules, so long as the state’s rules are not more restrictive than those in effect in January 1972. Section 209 (b) states must allow SSI beneficiaries to establish Medicaid eligibility through a spend-down by deducting unreimbursed out-of-pocket medical expenses from their countable income. Section 209 (b) states also must provide Medicaid to children who receive SSI and who meet the state’s financial eligibility rules for the AFDC program as of July 16, 1996. ↩︎

- Molly O’Malley Watts, et al., Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities in 2015 (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2016), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-financial-eligibility-for-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-in-2015/. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: MACPAC, June 2015), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/June-2015-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: MACPAC, June 2015), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/June-2015-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf. ↩︎

- [xiv] Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Medicaid Handbook: Interface with Behavioral Health Services (Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2013), http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA13-4773/SMA13-4773.pdf. ↩︎

- Julia Paradise and MaryBeth Musumeci, CMS’s Final Rule on Medicaid Managed Care: A Summary of Major Provisions (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2016), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/cmss-final-rule-on-medicaid-managed-care-a-summary-of-major-provisions/. ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, New Service Delivery Opportunities for Individuals with a Substance Use Disorder (Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, July 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/SMD15003.pdf. ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Medicaid Handbook: Interface with Behavioral Health Services (Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2013), http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA13-4773/SMA13-4773.pdf. ↩︎

- [xxii] MaryBeth Musumeci and Henry Claypool, Olmstead’s Role in Community Integration for People with Disabilities Under Medicaid: 15 Years After the Supreme Court’s Olmstead Decision (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation , June 2014), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/olmsteads-role-in-community-integration-for-people-with-disabilities-under-medicaid-15-years-after-the-supreme-courts-olmstead-decision/. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396u-7; 42 U.S.C. § 1396a (k) (1); 42 C.F.R. § § 440.300-440.390. Beneficiaries who are “medically frail” cannot be required to receive an ABP and instead must have access to the state plan benefit package. 42 U.S.C. § 1396u-7 (a) (2) (vi); 42 C.F.R. § 440.315 (f). ↩︎

- States that expanded Medicaid can choose to align their ABP for expansion adults with their Medicaid state plan benefit package. However, in states that do not align the two benefit packages, adult beneficiaries may have access to different behavioral health and other services based on their eligibility pathway. In these states, people who qualify for Medicaid both through a disability-related pathway and based on their low income can choose their coverage group and, therefore, their benefit package. ↩︎

- [xxv] MaryBeth Musumeci, Behavioral Health Parity and Medicaid (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2015), http://modern.kff.org/report-section/behavioral-health-parity-and-medicaid-issue-brief/. ↩︎

- [xxvi] CMS has published a final rule that applies federal mental health parity requirements to all Medicaid services provided to MCO enrollees, whether those services are delivered on a capitated or FFS basis. ↩︎

- [xxvii] Ken Cannon, Jenna Burton, and MaryBeth Musumeci, Adult Behavioral Health Benefits in Medicaid and the Marketplace (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/adult-behavioral-health-benefits-in-medicaid-and-the-marketplace/. ↩︎

- [xxviii] 42 U.S.C. § § 1396a (a) (43), 1396d (r) (5). ↩︎

- [xxix] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Medicaid Handbook: Interface with Behavioral Health Services (Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2013), http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA13-4773/SMA13-4773.pdf. ↩︎

- Vernon K. Smith, et al., Implementing Coverage and Payment Initiatives: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017 (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2016), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/implementing-coverage-and-payment-initiatives-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2016-and-2017/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- [xxxiii] Mike Nardone, Sherry Snyder, and Julia Paradise, Integrating Physical and Behavioral Health Care: Promising Medicaid Models (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2014) https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/integrating-physical-and-behavioral-health-care-promising-medicaid-models/. ↩︎

- [xxxiv] David Mechanic and Mark Olfson, “The Relevance of the Affordable Care Act for Improving Mental Health Care.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 12 (2016):515-42. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: MACPAC, March 2016), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/March-2016-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf. ↩︎

- Center for Health Care Strategies, Medicaid Health Homes: Implementation Update, (Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., January 2017), http://www.chcs.org/media/Health_Homes_FactSheet-01-18-17.pdf. ↩︎

- Molly O’Malley Watts, et al., Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities in 2015 (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2016), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-financial-eligibility-for-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-in-2015/. ↩︎

- MaryBeth Musumeci and Henry Claypool, Olmstead’s Role in Community Integration for People with Disabilities Under Medicaid: 15 Years After the Supreme Court’s Olmstead Decision (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation , June 2014), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/olmsteads-role-in-community-integration-for-people-with-disabilities-under-medicaid-15-years-after-the-supreme-courts-olmstead-decision/. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Behavioral health services covered under HCBS waivers and 1915(i) SPAs (Washington, DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, September 2015), https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/behavioral-health-services-covered-under-hcbs-waivers-and-spas/. ↩︎

- Molly O’Malley Watts, Erica L. Reaves, and MaryBeth Musumeci, Money Follows the Person: A 2015 State Survey of Transitions, Services, and Costs (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/money-follows-the-person-a-2015-state-survey-of-transitions-services-and-costs/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation Analysis of 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. ↩︎

- [xlii] Lisa Clemans-Cope, et al, “The Expansion of Medicaid Coverage under the ACA: Implications for Health Care Access, Use, and Spending for Vulnerable Low-income Adults,” Inquiry 50, 2(2013):135-49. ↩︎

- Hefei Wen, Benjamin G. Druss, and Janet R. Cummings, “Effect of Medicaid Expansions on Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care among Low-Income Adults with Behavioral Health Conditions,” Health Services Research 50, 6(2015):1787-809. ↩︎

- [xliv] Katherine Baicker, et al., “The Oregon Experiment – Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes,” New England Journal of Medicine. 368, 18(2013):1713-22. ↩︎

- [xlv] Elizabeth Reisinger Walker, et al., “Insurance Status, Use of Mental Health Services, and Unmet Need for Mental Health Care in the United States,” Psychiatric Services, 66, 6(2015):578-84. ↩︎

- [xlvi] Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, September 2016), https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Report to Congress on the Nation’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Workforce Issues (Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, January 2013), https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/PEP13-RTC-BHWORK/PEP13-RTC-BHWORK.pdf. ↩︎

- Tara F. Bishop, et al., “Acceptance of Insurance by Psychiatrists and the Implications for Access to Mental Health Care,” JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 2(2014):176-81. ↩︎

- Richard G. Frank, Kirsten Beronio, and Sherry A. Glied, “Behavioral Health Parity and the Affordable Care Act,” Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 13, 1-2(2014):31-43. ↩︎

- Ramin Mojtabai, Mark Olfson, Nancy Sampson, et al., “Barriers to Mental Health Treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication,” Psychological Medicine, 41, 8(2011):1751-61. ↩︎

- Ramin Mojtabai, Lian Yu Chen, Christopher Kaufmann, et al., “Comparing Barriers to Mental Health Treatment and Substance Use Disorder Treatment Among Individuals with Comorbid Major Depression and Substance Use Disorders,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46, 2(2014)268-73. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, The Role of Medicaid for People with Behavioral Health Conditions (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2012), https://modern.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8383_bhc.pdf. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Full-benefit dual eligibles and seniors were included; however, partial-benefit enrollees and states with incomplete or low-quality managed care encounter data (11 states including DC) were excluded from the analysis. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: MACPAC, June 2015), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/June-2015-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf. ↩︎

- Tami L. Mark, Tracy Yee, Katharine R. Levit, et al. “Insurance Financing Increased for Mental Health Conditions But Not For Substance Use Disorders, 1986-2014,” Health Affairs (Millwood) 35, 6(2016):958-965. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office, H.R. 1628 American Health Care Act of 2017 Cost Estimate (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, May 2017), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr1628aspassed.pdf. ↩︎

- Ronald C. Kessler, et al., “Depression in the Workplace: Effects on Short-Term Disability,” Health Affairs, 18, 5(1999):163-71. ↩︎

- Neil Jordan, et al., “Economic Benefit of Chemical Dependency Treatment to Employers,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34, 3(2008):311-319. ↩︎

- Doris J. James and Lauren E. Glaze. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, December 2006), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. ↩︎

- Cheryl J. Cherpitel and Yu Ye, “Drug Use and Problem Drinking Associated with Primary Care and Emergency Room Utilization in the US General Population: Data from the 2005 National Alcohol Survey,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 97, 3(2008):226-230. ↩︎