Medicaid Reforms to Expand Coverage, Control Costs and Improve Care: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2015 and 2016

Emerging Delivery System and Payment Reforms

| Key Section Findings |

Tables 11 and 12 contain more detailed information on emerging delivery system and payment reform initiatives in place in FY 2014, implemented in FY 2015 or planned for FY 2016. These tables are also available in a downloadable PDF. |

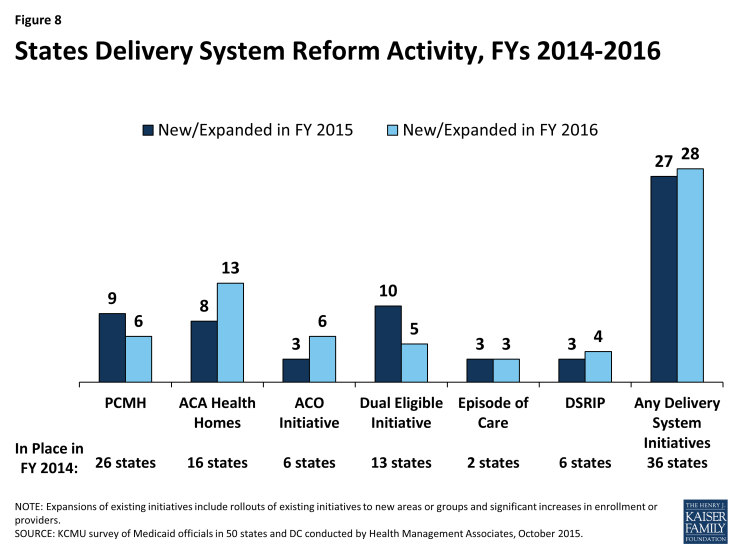

Interest in delivery system and payment reforms that hold the promise of improving health outcomes and constraining costs remains high among state Medicaid programs across the country. Twenty-seven (27) states in FY 2015 and 28 states in FY 2016 reported adopting or expanding one or more initiatives that seek to reward quality and encourage integrated care. Key initiatives include patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), Health Homes, and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). States are also implementing initiatives to coordinate care and financing for dual eligible beneficiaries. Episode of care and DSRIP initiatives are emerging delivery system reforms. This year’s survey asked states to identify which delivery system and payment reform models were in place in FY 2014, and whether they had adopted or were enhancing such models in FY 2015 or FY 2016. (Figure 8)

Patient-Centered Medicaid Homes (PCMHs)

Patient-centered medical home initiatives operated in half (26) of Medicaid programs in FY 2014. Under a PCMH model, a physician-led, multi-disciplinary care team holistically manages the patient’s ongoing care, including recommended preventive services, care for chronic conditions and access to social services and supports. Generally, providers or provider organizations that operate as a PCMH seek recognition from organizations like the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).1 PCMHs are often paid (by state Medicaid agencies directly or through MCO contracts) a PMPM fee in addition to regular FFS payments for their Medicaid patients.2

In this year’s survey, nine states reported having adopted or expanded PCMHs in FY 2015 and six states indicated plans to do so in FY 2016. Several of these states reported significant expansions. For example, Connecticut has made significant investments in recent years to help primary care practices obtain NCQA PCMH recognition. Over one-third of Connecticut’s Medicaid beneficiaries are served by PCMHs and the state is considering expanding the model beyond primary care. Wyoming, a state without MCO or PCCM programs, implemented PCMHs in FY 2015; the state is expanding the number of large practices participating. Idaho also reported expanding the number of practices participating in the state’s PCMH program, with the goal of covering 80 percent of the state’s population over the next four years. Other states with well-established managed care programs reported harmonizing PCMH requirements across their MCOs (Tennessee) and requiring MCOs to establish pilot medical homes for behavioral health, targeting adults with serious mental illness (Virginia).

In contrast, Massachusetts reported that its PCMH demonstration ended in March 2014, but was followed by the launch of the state’s three-year Primary Care Payment Reform Demonstration covering nearly 90,000 lives. Also, Pennsylvania reported that one of its MCOs participated in the CMMI Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice demonstration (that included Medicaid) that ended in 2014, but is considering expanding PCMH payments under future managed care contracts.

ACA Health Homes

Nearly one-third of states (16) had at least one Health Home initiative in place in FY 2014. This option, created under Section 2703 of the ACA, builds on the PCMH concept. It requires states to target beneficiaries who have at least two chronic conditions (or one and risk of a second, or a serious and persistent mental health condition), and provide a person-centered system of care that facilitates access to and coordination of the full array of primary and acute physical health services, behavioral health care, and long-term services and supports. This includes services such as comprehensive care management, referrals to community and social support services and the use of Health Information Technology (HIT) to link services, among others. States receive a 90 percent federal match rate for qualified Health Home service expenditures for eight quarters under each Health Home state plan amendment; states can (and have) created more than one Health Home program to target different populations.

In this survey, eight states reported having adopted or expanded Health Homes in FY 2015 and 13 states reported plans to do so in FY 2016. Nearly all states noted that they were focusing their Health Home programs on populations with behavioral health conditions. States are also incorporating Health Homes into larger reform efforts related to integrating physical and behavioral health. For example, Tennessee is planning to implement Health Homes statewide for individuals with severe and persistent mental illness in 2016; this is part of a larger effort to develop a multi-payer PCMH program that the state plans to expand statewide by 2018.

Two states reported that they ended their Health Homes during this period. Oregon ended its Health Home initiative on September 30, 2013, when the enhanced federal payments ended, but the state continues to expand the use of PCMHs. Washington’s Health Home program, which provided additional coordination and other Health Home services for those dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid as well as other Medicaid beneficiaries with at least one chronic condition and at risk of developing another, is ending December 31, 2015. The state is working with beneficiaries to transition them to other care management services.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

States continue to experiment with accountable care organizations as the concept evolves. Six states reported having ACO models in place for at least some of their Medicaid beneficiaries in FY 2014. While there is currently no uniform, commonly accepted federal definition of an ACO, an ACO generally refers to a group of health care providers or, in some cases, a regional entity that contracts with providers and/or health plans, that agrees to share responsibility for the health care delivery and outcomes for a defined population.3 An ACO that meets quality performance standards that have been set by the payer and achieves savings relative to a benchmark can share in the savings. The organizational structure of ACOs varies, but ACOs generally include primary and specialty care physicians and at least one hospital. Virtually all states with ACO initiatives built on existing care delivery programs (e.g., PCCM, medical homes, MCOs) that already involved some degree of coordination among providers and likely had key infrastructure to facilitate coordination among ACO providers (e.g., electronic medical records). States use different terminology in referring to their Medicaid ACO initiatives, such as Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) in Oregon and Regional Care Collaborative Organizations (RCCOs) in Colorado.4

In this survey, three states reported adopting or expanding ACOs in FY 2015 and six states reported such activity in FY 2016. This includes states like Maine, Massachusetts, and New Jersey that have implemented or are planning to implement new ACO models. Utah reported plans to expand their ACO model to new counties. Other states reported ACO activity spurred by MCO contract requirements (Iowa, New Mexico and Minnesota) or as part of larger Section 1115 waiver proposals (California).

| New Jersey ACO Demonstration |

| In July 2015, New Jersey kicked off the Medicaid ACO Demonstration Project, which focuses on improving health outcomes, quality and access to care through regional collaboration, and shared accountability while reducing costs. The Medicaid ACO Demonstration Project provides the New Jersey Medicaid program an opportunity to explore innovative system re-design including: testing the ACO as an alternative to managed care; evaluating how care management and care coordination could be delivered to high-risk, high-cost utilizers; stretching the role of Medicaid beyond medical services to integrate social services; and testing payment reform models including pay for performance metrics and incentives. |

Care Coordination and Integration of Care for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

Coordinating care for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligible beneficiaries) is a significant issue for Medicaid programs. These individuals tend to have significant health needs, a high prevalence of chronic conditions and substantial need for long-term services and supports. Prior to the ACA, coordination of care for individuals with dual enrollment in Medicaid and Medicare had been difficult to pursue for states in part because of misalignment between Medicare and Medicaid laws. In addition, when states did develop approaches to better coordinate care, any resulting savings from improvements in acute care (such as reduced inpatient admissions, readmissions and emergency room visits) accrued to Medicare and were not shared with state Medicaid programs. Under Section 2602 of the ACA, CMS established the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office (MMCO) and initiated Financial Alignment Demonstrations (FADs) with interested states seeking to coordinate and improve care and control costs for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

In this survey, 13 states indicated that initiatives to coordinate care for dual eligible beneficiaries were in place in FY 2014, including seven with CMS FADs and seven with initiatives outside the CMS FAD that centered on enrolling this population in comprehensive MCOs or managed long-term care plans (one state had both a FAD and a non-FAD initiative). Ten states reported implementing or expanding an initiative to coordinate care for dual eligible beneficiaries in FY 2015, including six states with FADs, two of which (California and Texas) implemented or expanded other initiatives such as MLTSS outside of the FAD initiative. For FY 2016, five states are planning to implement or expand an initiative including one state planning a FAD. Initiatives outside of the FADs included alignment of Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans for dual eligible beneficiaries (D-SNPs) with Medicaid MCOs and enrollment of dual eligible beneficiaries in comprehensive Medicaid MCOs (for acute care services) or managed long-term care.

| Selected Dual Eligible Care Coordination Initiatives (Outside of Financial Alignment Demonstrations) |

| Arizona is working to increase alignment and improve service delivery for dual eligible beneficiaries by contractually requiring its health plans to also serve as Medicare Dual Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs) and promoting enrollment of dual eligible beneficiaries into the same health plan for both Medicaid and Medicare to the greatest extent possible. Enrolling in specialized duals-only Medicare plans allows individuals to receive all of their health care, including the payment for prescriptions and benefits, from a single, integrated source.

Florida reported contracting with a specialty Medicaid managed care plan beginning in FY 2015 that caters to dual eligible beneficiaries with chronic conditions. |

Episode-of-Care Initiatives

Unlike fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement where providers are paid separately for each service, or capitation where a health plan receives a per member per month (PMPM) payment intended to cover the costs for all covered services, an episode-of-care payment is linked to the care that a patient receives for a defined condition or health event (e.g., pregnancy and delivery, heart attack, or knee replacement). Episode-based payments usually involve payment for multiple services and providers and therefore create a financial incentive for physicians, hospitals and other providers to work together to improve patient care and manage costs. In this survey, two states (Arkansas and Tennessee) noted that an episode-of-care initiative was in place in FY 2014. Both states indicated that they continued to expand these initiatives in FY 2015 and FY 2016. New Mexico reported that a small pilot is being operated by some of the state’s MCOs in FY 2015 and Louisiana reported that one MCO planned a demonstration in partnership with a birthing hospital in FY 2016. Additionally, Ohio is currently in an episode-of-care reporting year; gain-sharing payments will begin in calendar year 2017.

Hospital Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) programs are another piece of the dynamic and evolving Medicaid delivery system reform landscape. DSRIP initiatives, which are part of broader Section 1115 demonstration waiver programs, provide states with significant funding to support hospitals and other providers in changing how they provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries. DSRIP waivers are not grant programs – they are performance-based incentive programs. Originally, DSRIP initiatives were more narrowly focused on funding for safety-net hospitals and often grew out of negotiations between states and HHS over the appropriate way to finance hospital care. Now, however, they are used to promote far more sweeping payment and delivery system reforms.

The first DSRIP initiatives were approved and implemented in California and Texas in 2010 and 2011, followed by New Jersey, Kansas and Massachusetts in 2012 and 2013. In this year’s survey, Massachusetts reported expanding its DSRIP program and New Mexico and New York reported implementing DSRIP programs in FY 2015. For FY 2016, California and New Mexico reported DSRIP enhancements while New Hampshire and Washington reported plans to seek approval for new DSRIP initiatives.

Other Initiatives

In addition to the initiatives discussed already, states reported other delivery system and payment reform initiatives. For example, some states reported including value-based purchasing requirements in their managed care contracts (Arizona, Iowa, Michigan, and Texas). Pennsylvania reported plans to include a “health-home like” program in its 2016 MCO contracts. Other states reported expanding telehealth services and use of community health workers (New Mexico), creating a coordinated point of entry for substance abuse disorder treatment services (New Jersey) and offering subsidies to enable ambulatory practices to access health information exchange services and achieve Meaningful Use (North Carolina).

| All-Payer Claims Database |

| All-payer claims database (APCD) systems are large-scale databases that systematically collect medical claims, pharmacy claims, dental claims (typically, but not always), and eligibility and provider files from both private and public payers. They can be a valuable tool for identifying areas to focus reform efforts and for other purposes. Ten states (Colorado, Massachusetts, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee and Virginia) reported having APCDs in place while two states (California and Washington) planned to implement APCDs in FY 2016. |

Table 11: Delivery System and Payment Reform Initiatives in Place in all 50 States and DC in FY 2014

| States | Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) |

ACA Health Homes | Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) | Dual Eligible Initiatives | Episode of Care Payments | Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Program (DSRIP) | Other Initiatives | Any of these Initiatives in Place in FY 2014 |

| Alabama | X | X | X | |||||

| Alaska | ||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | |||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | |||||

| California | X* | X | X | |||||

| Colorado | X | X | X* | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | X | ||||||

| Delaware | ||||||||

| DC | ||||||||

| Florida | ||||||||

| Georgia | ||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | ||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Illinois | X* | X | ||||||

| Indiana | ||||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | |||||

| Kansas | X | X | X | |||||

| Kentucky | ||||||||

| Louisiana | ||||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | |||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | |||||

| Massachusetts | X | X* | X | X | ||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | |||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Mississippi | ||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | ||||||

| Montana | ||||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | ||||||

| Nevada | ||||||||

| New Hampshire | ||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New York | X | X | X | |||||

| North Carolina | X | X | ||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||||

| Ohio | X | X* | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | ||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | ||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | X | ||||||

| South Dakota | X | X | ||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | |||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Utah | X | X | ||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Virginia | X | X* | X | |||||

| Washington | X | X* | X | |||||

| West Virginia | ||||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | |||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||

| Totals | 26 | 16 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 36 |

| NOTES: Dually Eligible Initiatives: X* = State is pursuing a Financial Alignment Demonstration. CA reported another dual initiative in place outside of the demonstration.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2015. |

||||||||

Table 12: Delivery System and Payment Reform Actions Taken in all 50 States and DC, FY 2015 and 2016

| States | Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) |

ACA Health Homes | Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) | Dual Eligible Initiatives | Episode of Care Payments | Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Program (DSRIP) |

Other Initiatives | Any New or Expanded Initiative | ||||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Alabama | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Alaska | ||||||||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| California | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Colorado | ||||||||||||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| DC | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Florida | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Georgia | ||||||||||||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||||||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Indiana | ||||||||||||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Kansas | ||||||||||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Maryland | ||||||||||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Mississippi | ||||||||||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Nebraska | ||||||||||||||||

| Nevada | ||||||||||||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New York | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| North Carolina | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||||||||||||

| Ohio | X* | X | ||||||||||||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Rhode Island | X* | X | ||||||||||||||

| South Carolina | X* | X | ||||||||||||||

| South Dakota | ||||||||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Texas | X* | X | ||||||||||||||

| Utah | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Vermont | ||||||||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Washington | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Wisconsin | ||||||||||||||||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Totals | 9 | 6 | 8 | 13 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 27 | 28 |

| NOTES: Expansions of existing initiatives include rollouts of existing initiatives to new areas or groups and significant increases in enrollment or providers. Dually Eligible Intiatives: X* = State is pursuing a Financial Alignment Demonstration. CA and TX reported other FY 2015 initiatives outside of the demonstration.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2015. |

||||||||||||||||