Medicaid Moving Ahead in Uncertain Times: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018

Executive Summary

Medicaid covers one in five Americans, accounts for one in six dollars spent on health care in the United States and more than half of all spending for long-term services and supports, and is a state budget driver as well as the largest source of federal revenues to states. Medicaid is constantly evolving as policymakers strive to improve program value and outcomes through delivery system reforms, respond to economic conditions or public health concerns (such as the opioid epidemic), or implement federal policy changes including those in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or other regulatory changes (like the recent Medicaid managed care rule). As states began state fiscal year (FY) 2018, Congress was debating major ACA repeal and replace legislation generating great uncertainty for states around Medicaid including the future of the ACA and financing for the Medicaid expansion as well as overall financing for the Medicaid program.

KFF #Medicaid budget survey has data on #opioids initiatives, provider rates, #managedcare & more

This report provides an in-depth examination of the changes taking place in Medicaid programs across the country during this time of uncertainty. The findings are drawn from the 17th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). This report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in FY 2017 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2018. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis.

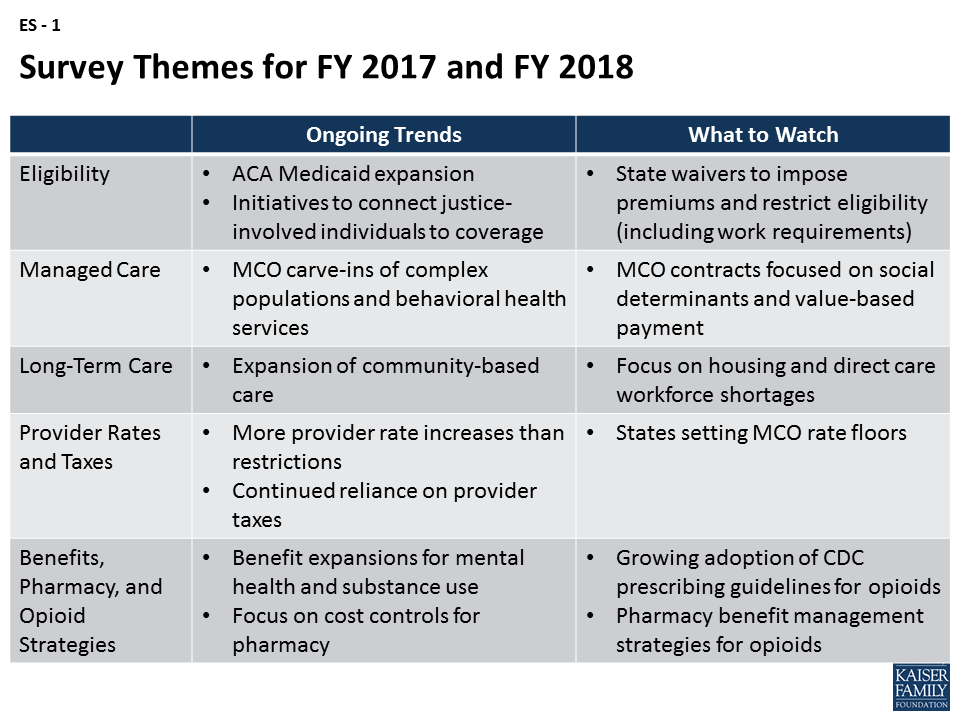

Key findings show that despite uncertainty about federal legislative changes, many states were continuing efforts to expand managed care, move ahead with payment and delivery system reforms, increase provider payment rates, and expand benefits as well as community-based long-term services and supports. Emerging trends include proposals to restrict eligibility (e.g., work requirements) and impose premiums through Section 1115 waivers, movement to include value-based purchasing requirements in MCO contracts, and efforts to combat the growing opioid epidemic. Key areas to watch include federal legislative efforts to restructure and limit federal Medicaid financing as well as Section 1115 waiver activity (state waiver proposals and CMS approvals). These issues will have implications for states, providers, and beneficiaries that could shape the future of the Medicaid program in FY 2018 and beyond (Figure ES – 1).

Eligibility Policies

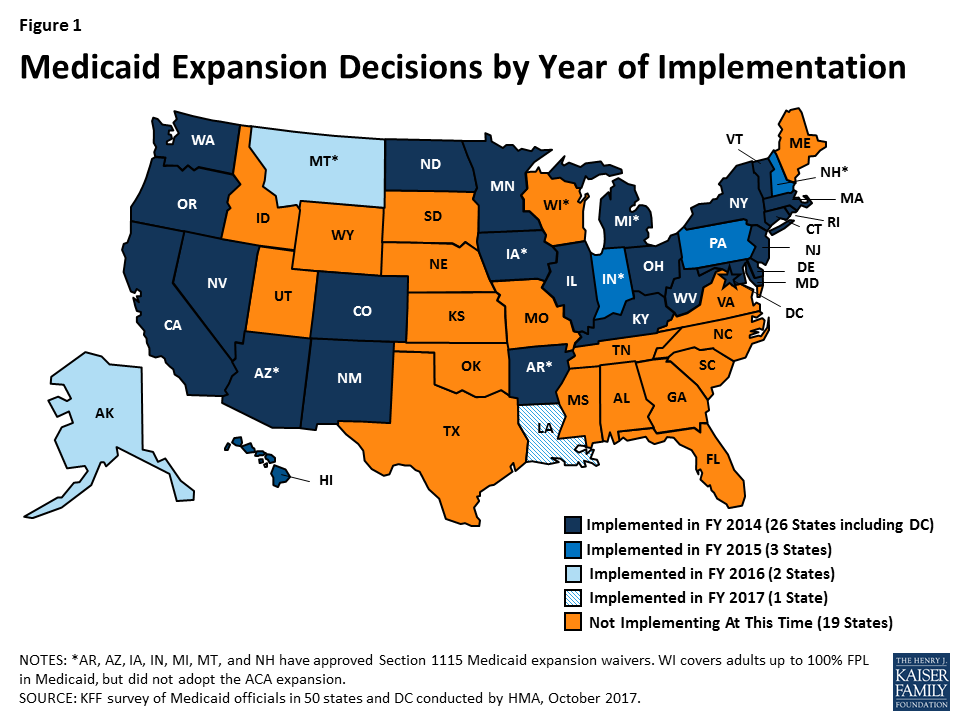

Since 2014, most major eligibility changes have been related to adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. To date, 32 states have implemented the expansion (Louisiana was the latest state to adopt the expansion in FY 2017). Largely because the Medicaid expansion made many individuals involved in the criminal justice system newly eligible for coverage (including childless adults who were not previously eligible in most states), many states have implemented policies to facilitate enrollment in Medicaid upon release and to suspend, rather than terminate, Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals. The majority of states also have policies in place to provide Medicaid coverage of inpatient care for those incarcerated in prisons or jails.

What to watch: Several non-expansion states (Idaho, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wyoming) reported this year that consideration of the Medicaid expansion was on hold due to uncertainty about the future of the Medicaid expansion option. For FY 2018, several states are seeking Medicaid eligibility restrictions through Section 1115 waivers, including conditioning eligibility on meeting work requirements,1 elimination of retroactive eligibility, and elimination of Medicaid expansion coverage for those with incomes above 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).2 Eligibility provisions in proposals in Arkansas and Indiana would apply to ACA Medicaid expansion populations and proposals in Iowa, Maine, and Utah would apply to non-expansion populations. Two states (Arkansas and Indiana) reported activity related to Medicaid premiums in FY 2017 or FY 2018, both through Section 1115 waivers.

Managed Care And Delivery System Reforms

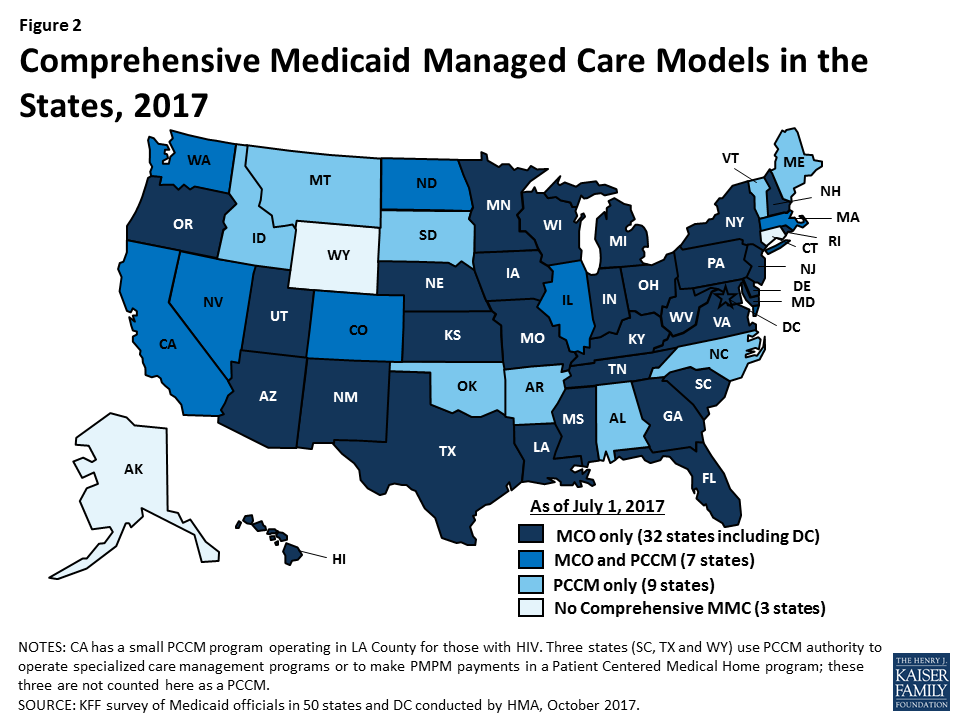

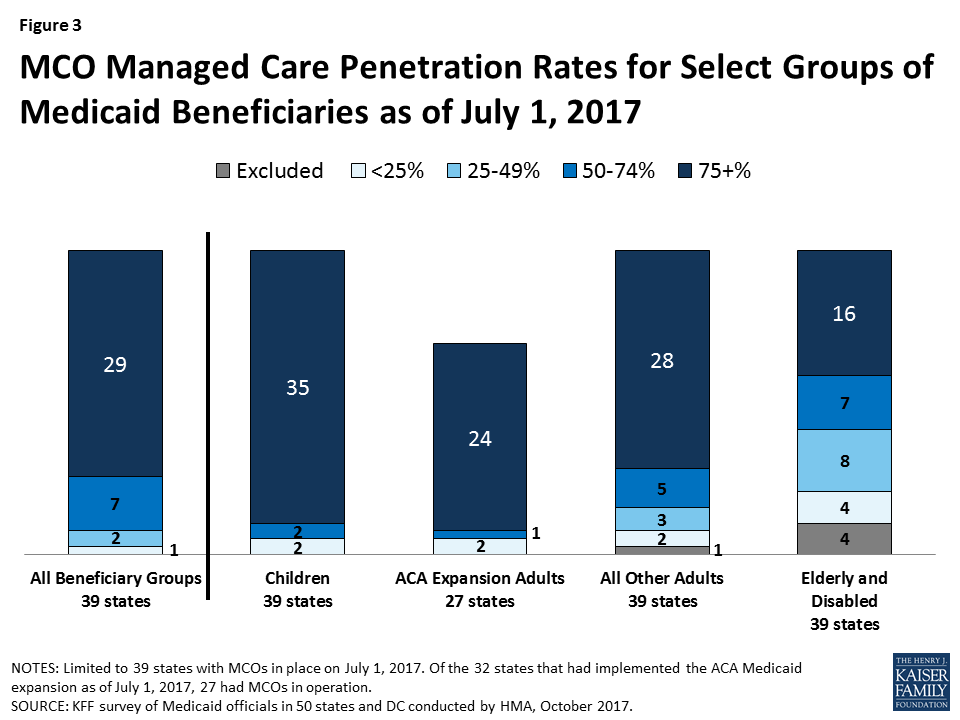

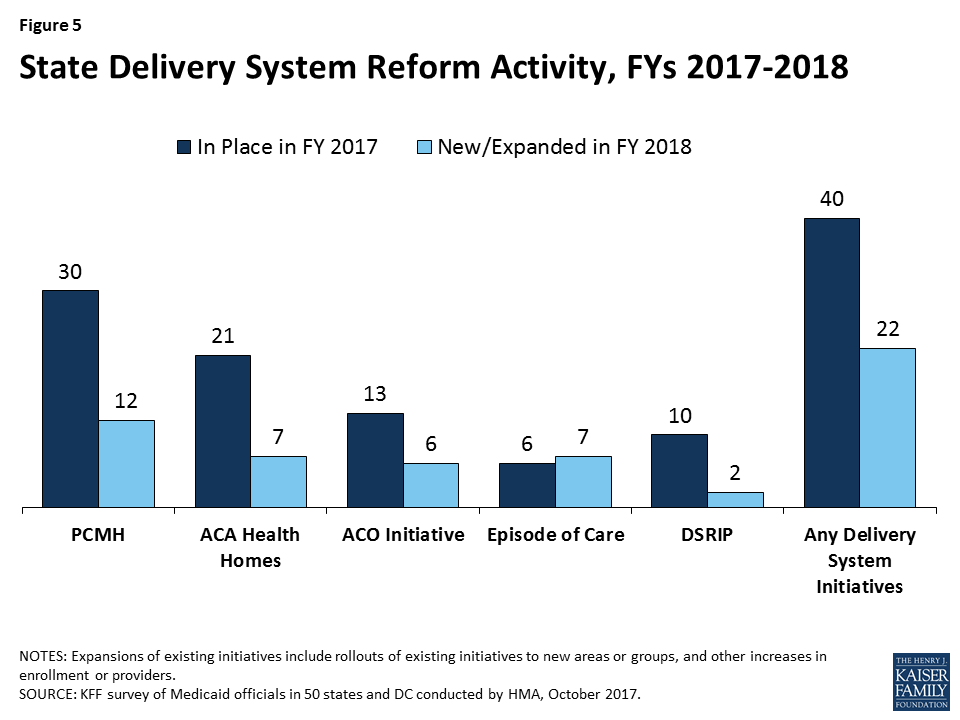

Managed care is the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. Among the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 29 states reported that 75 percent or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2017. More states continue to carve complex populations as well as behavioral health services into MCO contracts. Twenty-six of the 39 MCO states reported that they plan to use authority to receive federal matching funds for adults receiving inpatient psychiatric or substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in an institution for mental disease (IMD) for no more than 15 days a month included in the 2016 managed care regulations. Close to half of MCO states reported that the day limit is insufficient to meet acute inpatient or residential treatment needs for those with serious mental illness (SMI) or SUD.3 Nearly all states have managed care quality initiatives in place such as pay for performance or capitation withholds. Working in conjunction with or outside of MCO contracts, the majority of states (40) had one or more delivery system or payment reform initiative in place in FY 2017 (e.g., patient-centered medical home, ACA Health Home, accountable care organization, episode of care payment, or delivery system reform incentive program (DSRIP)).

What to watch: States are using MCO arrangements to increase attention to the social determinants of health and to promote value-based payment. States are increasingly requiring MCOs to: screen beneficiaries for social needs (19 states in FY 2017 and two additional states in FY 2018); provide care coordination pre-release to incarcerated individuals (six states in FY 2017 and one additional state in FY 2018); and use alternative payment models (APMs) to reimburse providers (13 states in FY 2017 set a target percentage of MCO provider payments that must be in APM and nine additional states plan to set a target in FY 2018). More than one in three states also have initiatives to expand dental access or improve oral health outcomes (for children and/or adults) and to expand the use of telehealth.

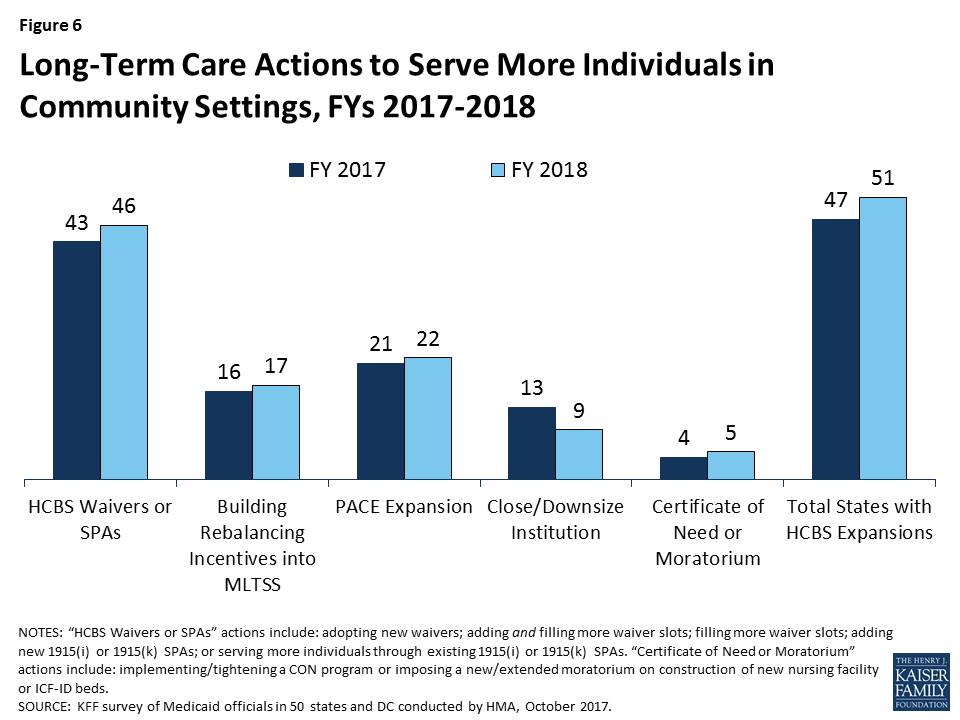

Long-Term Services And Supports (LTSS)

The vast majority of states in FY 2017 (47 states) and all states in FY 2018 are using a variety of tools and strategies to expand the number of people served in home and community-based settings. The most common strategies include using home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers or state plan options, serving more individuals through Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), and building rebalancing incentives into managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) contracts. Twenty-three states cover LTSS through one or more capitated managed care arrangements as of July 1, 2017.

What to watch: Housing supports are an increasingly important part of state LTSS benefits. Over half of states (27) reported that they implemented or expanded housing-related activities outlined in CMS’s June 2015 Informational Bulletin (e.g., housing transition services or housing and tenancy sustaining services) in FY 2017 or FY 2018 (up from 16 states reported last year). States are also focused on addressing LTSS direct care workforce shortages and turnover: 17 states reported efforts in FY 2017 or 2018 to increase wages for direct care workers and/or engage in targeted workforce development activities (recruiting, training, credentialing, etc.).

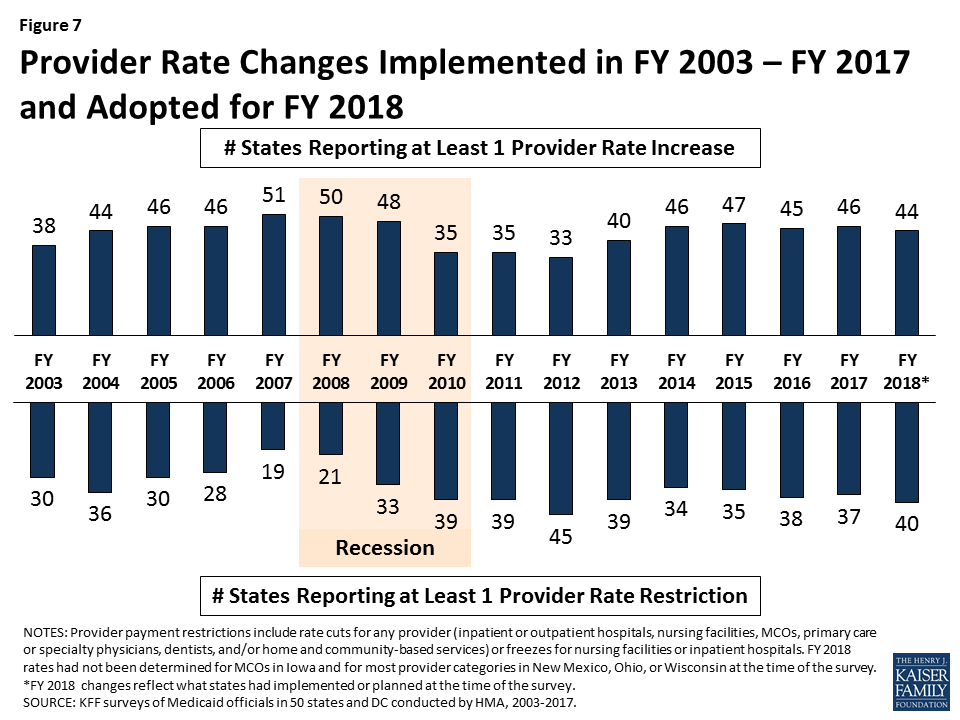

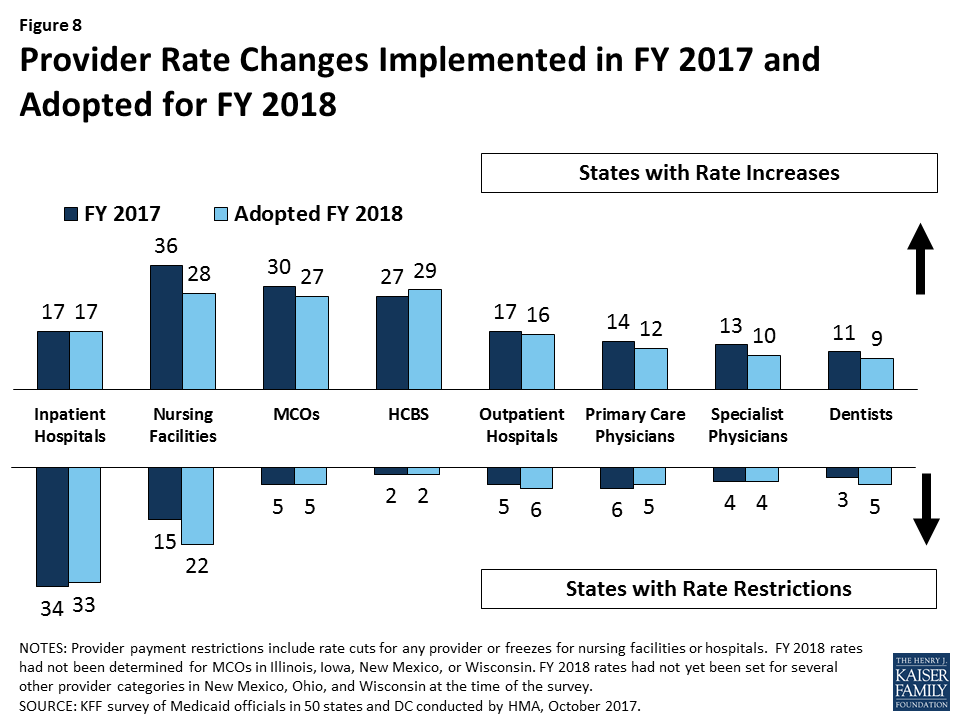

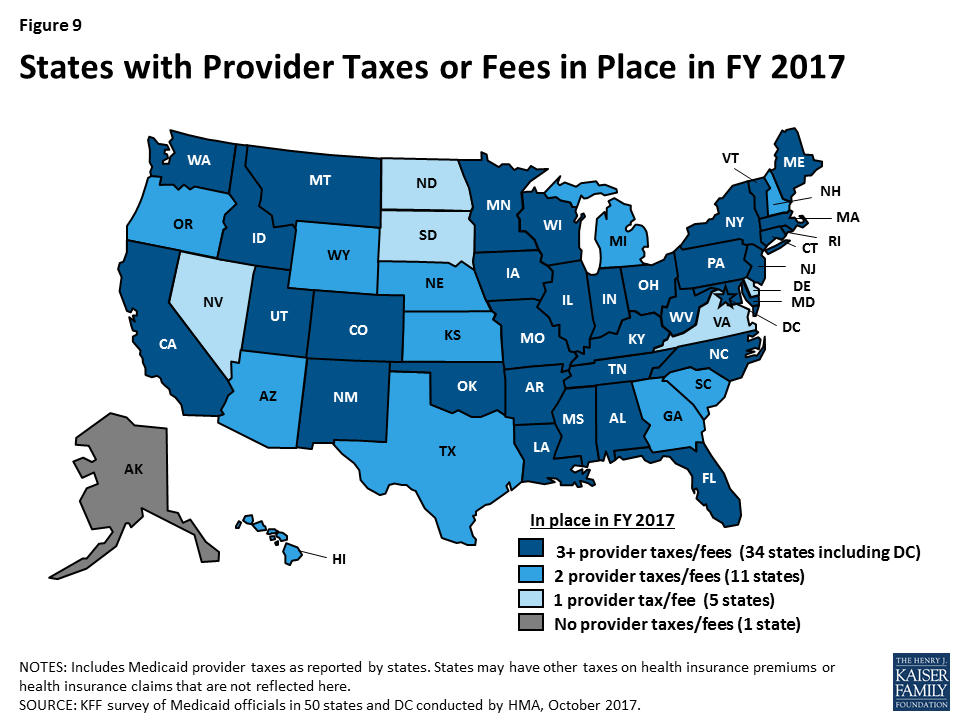

Provider Payment Rates And Taxes

In FY 2017 and FY 2018, more states made or are planning provider rate increases compared to restrictions across all provider types, except for inpatient hospital rates (hospital rate restrictions are primarily rate freezes, which are counted as restrictions in this report). All states except Alaska rely on provider taxes and fees to provide a portion of the non-federal share of the costs of Medicaid. Three states indicated plans for new provider taxes in FY 2018 and 13 states plan provider tax increases.

What to watch: Survey responses related to MCO rate setting show that 18 of 39 MCO states require MCO rates to follow fee-for-service (FFS) rate changes for some provider types, and two states require MCO rates to follow FFS rate changes for all provider types. Twenty-four states reported they had MCO rate floors for some provider types, and five states said they had rate floors for all types of Medicaid providers. Federal legislation considered in the Senate proposed limiting the use of provider taxes by lowering the “safe harbor threshold” from the current allowable level, 6.0 percent of net patient revenues, to 5.0 percent of net patient revenues by FY 2025 in one proposal and 4.0 percent by FY 2025 in another. The survey shows that 29 states reported having at least one provider tax exceeding 5.5 percent of net patient revenues and 46 states reported having at least one provider tax exceeding 3.5 percent as of July 1, 2017.

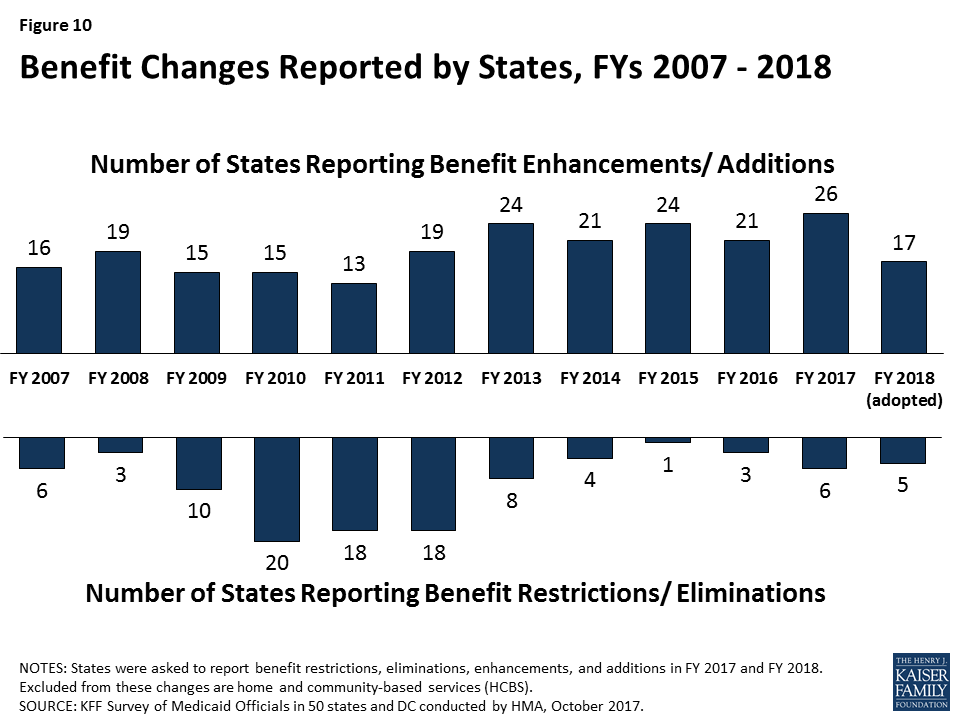

Benefits, Prescription Drugs, and Opioid Strategies

A total of 26 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in FY 2017 and 17 states plan to add or enhance benefits in FY 2018, most commonly for behavioral health/substance use disorder services and dental services. Thirteen states reported changes to copayment requirements in either FY 2017 or FY 2018, including new or increased copayments for enrollees with income above 100 percent FPL, for non-emergency use of a hospital emergency department, and pharmacy. Most states identified high cost and specialty drugs (including hepatitis C antivirals) as a significant cost driver for state Medicaid programs. The majority reported actions to refine and enhance their pharmacy programs, especially implementation of new utilization controls (e.g., prior authorization requirements, clinical edits, and quantity limits). Thirty-five of 39 MCO states reported that the pharmacy benefit was “generally carved-in.” Of these 35 states, the majority reported requirements that MCOs have uniform clinical protocols (31 states) or uniform preferred drug lists (PDLs) (19 states) that will be in place for one or more drugs as of the end of FY 2018.

What to watch: A growing number of states have chosen to adopt the CDC guidelines for the prescribing of opioid pain medications for adults in primary care settings (34 states as of the end of FY 2018). Nearly all states have various FFS pharmacy management strategies targeted at opioid harm reduction in place as of FY 2017, including quantity limits (48 states); clinical criteria claim system edits (46 states); step therapy (34 states); and other prior authorization requirements (32 states). Somewhat fewer states (28 states) reported requirements in place for Medicaid prescribers to check their states’ Prescription Drug Monitoring Program before prescribing opioids to a Medicaid patient. Among the 35 states that used MCOs to deliver pharmacy benefits, 24 reported that they required MCOs to follow some or all of their FFS pharmacy benefit management policies for opioids. For FY 2017, the vast majority of states (46 states) reported that naloxone (a prescription opioid overdose antidote) was available in at least one formulation without prior authorization (PA) and most states (42) also covered the naloxone nasal spray formulation without PA. The standard of care for opioid use disorder is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines psychosocial treatment with medication. All 49 states that responded to a new question about medication-assisted treatment (MAT) drugs reported coverage of buprenorphine and both oral and injectable naltrexone, but a somewhat smaller number (36 states) reported coverage of methadone in FY 2017.4

Looking Ahead

Medicaid is constantly evolving as policymakers strive to improve program value and outcomes through delivery system reforms, respond to economic conditions or public health concerns (such as the opioid epidemic), or implement federal policy changes including those in the ACA or other regulatory changes (like the recent Medicaid managed care rule). As states began FY 2018, Congress was debating major ACA repeal and replace legislation generating great uncertainty for states around Medicaid including the future of the ACA and financing for the Medicaid expansion as well as overall financing for the overall Medicaid program. On this year’s survey, Medicaid directors were asked to comment on state-specific implications of federal proposals. Most Medicaid directors from the 32 ACA Medicaid expansion states reported that they would not be able to continue covering the expansion population, or that coverage would be at substantial risk, if the ACA enhanced federal match for this population were terminated. Almost all Medicaid directors expressed concern about the likely negative fiscal consequences tied to proposed limits on federal Medicaid spending. Some directors mentioned that they welcomed potential new state policy flexibility under federal legislative proposals, but a greater number of Medicaid directors expressed concern that proposals to convert Medicaid to a per capita cap or block grant would not provide sufficient flexibility to enable states to make up for the reduction in federal funds.

Despite the uncertain policy environment, many states continue efforts to expand managed care, move ahead with payment and delivery system reforms, increase provider payment rates, expand benefits, and expand community-based LTSS. Emerging trends from this year’s survey include proposals to restrict eligibility (e.g., work requirements) and impose premiums through Section 1115 waivers, movement to include value-based purchasing requirements in MCO contracts, and efforts to combat the growing opioid epidemic. Key areas to watch include federal legislative efforts to restructure and limit federal Medicaid financing as well as Section 1115 waiver activity (state waiver proposals and CMS approvals). These issues will have implications for states, providers, and beneficiaries that could shape the future of the Medicaid program in FY 2018 and beyond.

Report: Introduction

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage to more than one in five Americans, and accounting for over one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures.5 The Medicaid program constantly evolves, as policy makers in each state make changes to improve their programs, respond to economic conditions, come into compliance with new federal requirements, and implement other state budget and policy priorities. As fiscal year (FY) 2018 began in most states, legislative proposals to repeal major portions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), including the Marketplace and Medicaid coverage expansions, were under consideration in Congress. These proposals would also have fundamentally restructured federal Medicaid financing, converting the current open-ended entitlement to a federal block grant or per capita cap. It is within that context that this year’s survey was conducted.

This report examines the reforms, policy changes, and initiatives that occurred in FY 2017 and those adopted for implementation for FY 2018 (which began for most states on July 1, 20176 ). Report findings are drawn from the annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). This was the 17th annual survey, which has been conducted from FY 2002 through FY 2018. (Copies of previous reports are archived here.7 )

The KFF/HMA Medicaid survey on which this report is based was conducted from June through September 2017. The survey was sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2017. Directors and their staff provided data for this report in their written survey response and through a follow-up telephone interview. All 50 states and DC completed surveys and participated in telephone interview discussions between July and September 2017. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis. An acronym glossary and the survey instrument are included as appendices to this report.

The survey collects data about Medicaid policies in place or implemented in FY 2017, policy changes implemented at the beginning of FY 2018, or policy changes for which a definite decision has been made to implement in FY 2018. Some policies adopted for the upcoming year are occasionally delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems or political considerations, or due to delays in approval from CMS. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report; the counts of state policies or policy actions that are interspersed throughout this report include survey responses from the 51 “states” (including DC). Key findings of this survey, along with state-by-state tables providing more detailed information, are described in the following sections of this report:

Report: Eligibility And Premiums

Key Section Findings

Since 2014, most major eligibility changes have been related to adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. To date, 32 states have implemented the expansion (Louisiana was the latest state to adopt the expansion in FY 2017). Only a few states adopted other Medicaid eligibility expansions for FYs 2017 or 2018, and these changes were generally narrow in scope and targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. The majority of states have policies in place to provide Medicaid coverage of inpatient care for those incarcerated in prisons or jails, to facilitate enrollment in Medicaid upon release, and to suspend, rather than terminate, Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals.

What to watch:

- For FY 2018, several states are seeking Medicaid eligibility restrictions through Section 1115 waivers that apply to ACA Medicaid expansion and/or traditional Medicaid populations, including the addition of work requirements, elimination of retroactive eligibility, and elimination of Medicaid expansion coverage for those with income above 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).8 Several non-expansion states reported that consideration of the Medicaid expansion was on hold due to uncertainty about the future of the Medicaid expansion option.

- Two states reported activity related to premiums in FY 2017 or FY 2018, both through Section 1115 waivers.

Tables 1, 2, and 3 at the end of this section include additional details on eligibility and premium policy changes in FYs 2017 and 2018.

Changes to Eligibility Standards

The ACA Medicaid expansion was one of the most significant Medicaid eligibility changes in the history of the program. By FY 2017, 32 states had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion: 26 states in FY 2014; three states (Indiana, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania) in FY 2015; two states (Alaska and Montana) in FY 2016, and one state (Louisiana) on July 1, 2016 (FY 2017) (Figure 1).

Several non-expansion states (Idaho, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wyoming) reported that consideration of the Medicaid expansion was on hold due to uncertainty about the future of the Medicaid expansion option. North Carolina’s governor announced plans to adopt the expansion shortly after taking office in January 2017. These plans have been delayed, however, by a lawsuit brought by a group of legislators challenging the governor’s authority to expand without legislative approval.9 In Maine, voters will decide whether the state will adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in a referendum this November.10

Other Eligibility Expansions

Beyond the ACA Medicaid expansion, states have made very few changes to expand Medicaid eligibility since 2014, and states reported only a few narrow expansions targeting a limited number of beneficiaries implemented in FY 2017 or planned for FY 2018 (Tables 1 and 2).

In addition to the ACA Medicaid expansion in Louisiana, a total of six other states made changes that expanded Medicaid eligibility in FY 2017. For FY 2018, seven states plan to implement eligibility expansions. Notable expansions reported include the following:

- In FY 2017, both Florida and Utah implemented the option to eliminate the five-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children. Arkansas and Nevada both intend to implement this option in FY 2018 (pending CMS approval of their plans, which were adopted by both states’ legislatures during FY 2017).

- In FY 2018, a pending Section 1115 waiver in Utah proposes covering a new eligibility group: individuals with income below 5 percent of the FPL who are chronically homeless, justice-involved, or individuals in need of substance use and/or mental health treatment.

Eligibility Restrictions

Only one state reported implementing an eligibility restriction in FY 2017: Missouri suspended its family planning waiver11 in FY 2017 following legislative restrictions contained in the state’s FY 2017 appropriations bill.12 Although Missouri replaced the Medicaid family planning waiver with a state-funded family planning program, this change eliminated Medicaid coverage for family planning services and placed new restrictions on which providers are accessible to the population. (The new restrictions apply only to individuals eligible through the waiver, however, and do not affect coverage of family planning services for other Medicaid eligible individuals.)

Eight states reported eligibility restrictions for FY 2018 (six states through Section 1115 waivers and two states through state plan authority), some in response to a March 2017 Trump administration letter to state governors13 that signaled an openness to approve Section 1115 waivers that include work requirements and more expansive use of premiums and cost sharing. This year’s survey captured changes that states have implemented or plan to implement in FY 2018, even if these changes are included in Section 1115 Waiver proposals that are pending approval 14 at CMS. Waiver provisions (in approved or pending waivers) that states plan to implement in FY 2019 or after are described later in the “Challenges and Priorities” section of this report.15 A description of key eligibility restrictions included in pending Section 1115 waivers planned for FY 2018 implementation follows.

FY 2018 restrictions for ACA Medicaid expansion populations:16

- Arkansas 17 has proposed to amend its “Arkansas Works” Medicaid expansion waiver to: (1) eliminate coverage for persons with income above 100 percent of the FPL while still maintaining the enhanced federal matching rate for the remaining expansion population at or below 100 percent FPL, (2) include a work requirement for the remaining expansion population, and (3) eliminate the conditions CMS placed on the state’s waiver of retroactive eligibility for expansion enrollees (including the medically frail).18

- Indiana 19 plans to impose a three-month lock-out from coverage on individuals who fail to comply with redetermination requirements. Beneficiaries who fail to verify eligibility at renewal would be disenrolled but could re-enroll without a new application if they provide necessary documentation within 90 days. After 90 days, a three-month lock-out period would follow before individuals could re-enroll.20

FY 2018 restrictions for non-ACA expansion Medicaid populations:

- Iowa plans to eliminate retroactive Medicaid eligibility for all Medicaid enrollees with an October 1, 2017 target implementation date.21

- Maine 22 plans to: (1) waive retroactive eligibility so that coverage would begin no earlier than the first day of the month of application, (2) impose a work requirement for adults (ages 19 to 64), such as parents and former foster care youth, and a time limit on coverage for those who fail to comply with work requirement, (3) apply a $5,000 asset test to all coverage groups that currently do not have an asset test, and (4) eliminate hospital presumptive eligibility for all coverage groups. The state’s pending waiver application proposes to implement these initiatives within six months of demonstration approval (the state’s estimated start date is January 1, 2018).23

- Utah plans to impose a work requirement for its existing Primary Care Network (PCN) waiver adults,24 impose a 60-month time limit on eligibility for PCN adults, and end hospital presumptive eligibility for all current enrollees.

Utah’s Proposed Section 1115 Limited Medicaid Coverage Expansion

A pending Section 1115 waiver in Utah proposes covering a new eligibility group: individuals with income below 5 percent of the FPL who are chronically homeless, justice-involved, or individuals in need of substance use and/or mental health treatment. The state also plans to implement the following restrictive policies for this proposed new childless adults coverage group: 60-month time limit on coverage; no retroactive eligibility; and no hospital presumptive eligibility. Implementation is proposed for January 1, 2018.25

Premiums

The Medicaid statute generally does not allow states to charge premiums to Medicaid beneficiaries. Only two states reported activity related to Medicaid premiums in either FY 2017 or FY 2018.26 In FY 2017, Arkansas replaced the requirement that expansion enrollees make contributions to “Health Independence Accounts” with a new 2 percent of income premium requirement (up to $13/month) for expansion enrollees above 100 percent FPL. Indiana’s pending waiver includes requests to: (1) add a 1 percent premium surcharge for tobacco users beginning in the second year of enrollment, (2) require Transitional Medical Assistance parents with income up to 138 percent FPL to pay premiums like expansion adults, and (3) change to a tiered premium structure instead of a flat charge of 2 percent of income (this change is planned for FY 2018 and expected to have a neutral effect on beneficiaries) (Table 2).

Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population

In recent years, many states have implemented new policies to connect individuals involved with the criminal justice system to Medicaid given that the Medicaid expansion made many of these individuals newly eligible for coverage (including childless adults who were not previously eligible in most states). Connecting these individuals to health coverage27 can facilitate their integration back into the community. Individuals may be enrolled in Medicaid while they are incarcerated, but Medicaid cannot cover the cost of their care during their period of incarceration, except for inpatient services. Nearly all states have policies in place to cover inpatient care for individuals who are incarcerated under Medicaid. Most states are also working with corrections agencies and with local jails to facilitate enrolling individuals in Medicaid before they are released. In addition, half of the states (25) have enrollment initiatives to facilitate Medicaid enrollment for parolees. Some states train criminal justice employees to assist with Medicaid applications and other states have dedicated Medicaid staff to work with the corrections agencies to facilitate enrollment for inmates or payment for inpatient care of inmates. Finally, the majority of states suspend rather than terminate Medicaid coverage for enrollees who become incarcerated. When coverage is suspended, it can be reinstated more easily and quickly upon release from incarceration or when an inpatient hospital stay occurs.28

While both Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states have adopted these strategies to connect justice-involved individuals to Medicaid coverage, these initiatives affect many more people in expansion states because eligibility for adults remains restrictive in non-expansion states. In this year’s survey, one non-expansion state commented that the administrative costs of implementing Medicaid coverage policies for the criminal justice population would be excessive since the policies would apply to such a small number of people in the state.

Details on Medicaid coverage for individuals involved with the criminal justice system are included in Exhibit 1 and Table 3.

| Exhibit 1: Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population in FY 2017 and/or FY 2018 (# of States) | |||

| Select Medicaid Coverage Policies for the Criminal Justice Population | Jails | Prisons* | Parolees |

| Medicaid coverage for inpatient care provided to incarcerated individuals | 41 | 47 | N/A |

| Medicaid outreach/assistance strategies to facilitate enrollment prior to release from incarceration or for parolees | 33 | 40 | 25 |

| Eligibility suspended (rather than terminated) for Medicaid enrollees who become incarcerated^ | 36 | 37 | N/A |

| ^States that continue Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals but limit covered benefits to inpatient hospitalization are also included in the count of states that suspend eligibility. *The District of Columbia has jails but not a prison system. However, DC is counted under Medicaid outreach/assistance strategies because some individuals who serve prison terms outside of DC may be placed in residential re-entry centers upon returning to DC and may apply for Medicaid to access coverage for 24-hour inpatient care and to facilitate enrollment prior to release. | |||

Louisiana Medicaid and Corrections Policies

Louisiana has implemented several strategies to increase coverage and access to care for individuals released from incarceration, particularly those with high health care needs.Louisiana Medicaid shares data with the Louisiana Department of Corrections (LDOC), which adds incarceration and release dates to the Medicaid eligibility system. As a result of this data sharing, the state Medicaid agency can automatically identify individuals pre-release and begin planning nine months before the scheduled release date. Additionally, in FY 2017 the state began using a new system and streamlined application to enroll state prisoners in Medicaid prior to release and connect them to a health plan. As part of this process, the system also identifies high need individuals for discharge planning/case management. There are “high needs” markers for those with serious mental illness, substance use disorder, co-morbid medical conditions, or those who are “bed bound”. The Medicaid health plans are required to do pre-release care planning and ensure that there will be sufficient medications available at discharge for these high-need individuals.

Plans are underway to expand outreach/ enrollment assistance to local jails in FY 2018.

Table 1: Changes to Eligibility Standards in all 50 States and DC, FY 2017 and FY 2018

| Eligibility Standard Changes | ||||||

| States | FY 2017 | FY 2018 | ||||

| (+) | (-) | (#) | (+) | (-) | (#) | |

| Alabama | ||||||

| Alaska | ||||||

| Arizona | ||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | |||

| California | ||||||

| Colorado | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | ||||||

| Delaware | ||||||

| DC | ||||||

| Florida | X | |||||

| Georgia | ||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||

| Idaho | X | |||||

| Illinois | ||||||

| Indiana | X | X | ||||

| Iowa | X | |||||

| Kansas | ||||||

| Kentucky | ||||||

| Louisiana | X-Medicaid Expansion | |||||

| Maine | X | X | ||||

| Maryland | ||||||

| Massachusetts | X | |||||

| Michigan | ||||||

| Minnesota | X | |||||

| Mississippi | ||||||

| Missouri | X | X | ||||

| Montana | ||||||

| Nebraska | ||||||

| Nevada | X | |||||

| New Hampshire | ||||||

| New Jersey | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | |||||

| New York | ||||||

| North Carolina | ||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||

| Ohio | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | ||||||

| Oregon | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | ||||||

| Rhode Island | ||||||

| South Carolina | ||||||

| South Dakota | ||||||

| Tennessee | ||||||

| Texas | ||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | |||

| Vermont | ||||||

| Virginia | X | X | ||||

| Washington | ||||||

| West Virginia | ||||||

| Wisconsin | ||||||

| Wyoming | X | |||||

| Totals | 7 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| NOTES: From the beneficiary’s perspective, positive changes counted in this report are denoted with (+), negative changes are denoted with (-), and neutral changes are denoted with (#). This table captures eligibility changes that states have implemented or plan to implement in FY 2017 or 2018, including changes that are part of pending Section 1115 waivers. For pending waivers, only provisions planned for implementation before the end of FY 2018 (according to waiver application documents) are counted in this table. Waiver provisions in pending waivers that states plan to implement in FY 2019 or after are not counted here.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2017. | ||||||

Table 2: States Reporting Eligibility29 and Premium30 Changes in FY 2017 and FY 201831

| State | Fiscal Year | Eligibility Changes |

| Arkansas | 2017 | Premiums (New only for expansion population, under Sec. 1115 waiver): Arkansas Works program ended prior required contributions to “Health Independence Accounts” and replaced them with a 2% premium requirement for expansion populations with income 100-133% FPL (up to $13/month). Non-payment does not affect eligibility, but a debt to the state is accumulated (1/1/2017). |

| 2018 | Expansion Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate the conditions CMS placed on the state’s waiver of retroactive eligibility for expansion enrollees (including the medically frail), effective 1/1/2018 (60,000 individuals).32 Expansion Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate coverage for expansion population with income 100-133% FPL. (Implementation phased based on redetermination date.) Expansion Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Work requirement for “remaining” expansion adults (0-100% FPL), similar to SNAP program. Expansion Adults (#) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: End premium assistance program for employer sponsored insurance (40 individuals). Children (+): Implement the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children. | |

| Colorado | 2017 | Adults (+): Implementing annualized income for eligibility for MAGI populations (affects 3,000). |

| 2018 | Aged & Disabled (+) Planned Sec. 1115 Waiver: Medicaid buy-in option for individuals in support living services, spinal cord injury, & brain injury waivers. | |

| Florida | 2017 | Children (+): Implement the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children. |

| Idaho | 2018 | Children (+): Cover children with severe emotional disorder in families with income between 185 and 300% FPL (1,000 children). |

| Indiana | 2018 | Expansion Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Three-month lock-out of coverage following a 90-day period of disenrollment for failure to comply with redetermination requirements. Expansion Adults (#): End HIP Link premium assistance program for Employer Sponsored Insurance. (Enrollees will be moved to other HIP 2.0 coverage). Premiums (New) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Require Transitional Medical Assistance parents up to 138% FPL to pay premiums like expansion adults. Premiums (New) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add a 1% premium surcharge for tobacco users beginning in the second year of enrollment. Premiums (Neutral for Expansion Population) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Seeking a tiered contribution amount instead of flat 2% of income, effective February 1, 2018 for the HIP 2.0 program. |

| Iowa | 2018 | All Groups (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate retroactive eligibility, target effective date 10/1/17. |

| Louisiana | 2017 | Expansion Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion on July 1, 2016 (430,000 individuals). |

| Maine | 2017 | Adults (+): Increased eligibility under family planning pathway to 209% FPL. |

| 2018 | Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add a work requirement for many groups of adults ages 19-64: parents, former foster care youth, individuals receiving transitional medical assistance, medically needy parents/caretakers, individuals eligible for family planning services only, and individuals with HIV. Those who fail to comply with work requirement would be limited to no more than 3 months in a 36-month period. All Groups (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate retroactive eligibility. Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Apply a $5,000 asset test to all coverage groups that do not currently have an asset test (under current law there is no asset test for coverage groups based solely on low income (vs. old age/disability)). All Groups (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate hospital presumptive eligibility. | |

| Massachusetts | 2018 | Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate 90 day period of provisional eligibility for adults under age 65 without verified income who are not either pregnant or HIV positive (130,000).33 |

| Minnesota | 2017 | Aged & Disabled (+): Increased income standard for the medically needy from 75% FPL to 80% FPL on 7/1/2016. Adults (+): Added optional Medicaid eligibility group for family planning for those with income up to 278% FPL. |

| Missouri | 2017 | Adults (-): Family Planning Waiver ended and replaced with a state-only (non-Medicaid) program. |

| 2018 | Aged & Disabled (+): Asset limit doubled (10,005 individuals). | |

| Nevada | 2018 | Children (+): Implement the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children. |

| New Mexico | 2018 | Aged & Disabled (-): Home equity exclusion changed from the federal maximum of $840,000 to the federal minimum of $560,000 (Fewer than 5 individuals). |

| Ohio | 2017 | Aged & Disabled (#): Conversion from 209(b) to 1634 for SSI related groups. |

| Utah | 2017 | Children (+): Implementing the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children (Estimated to affect 750 children). |

| 2018 | Parents & Caretakers (+): Increased the Basic Maintenance Standard to 55% FPL (3,000 individuals). Adults (+) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: New eligibility group for chronically homeless, justice-involved individuals and those in need of substance abuse and/or mental health treatment, with income below 5% FPL. Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add a work requirement for Primary Care Network (PCN) group. Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate of retroactive eligibility for PCN adults. Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add 60-month limit on eligibility for PCN adults. Current Enrollees (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate hospital presumptive eligibility. | |

| Virginia | 2017 | Disabled (+) Under Sec. 1115 Waiver: Increased eligibility from 60% to 80% FPL for waiver services for people with serious mental illness (GAP waiver program). (Note: had been decreased from 100% FPL to 60% FPL in FY 2016.) |

| 2018 | Disabled (+) Under Sec. 1115 Waiver: Increase eligibility from 80% to 100% FPL for waiver services for people with serious mental illness (GAP waiver program) (2,000 adults with SMI). (Full restoration to pre-2016 level.) | |

| Wyoming | 2018 | Adults (-): Income level for Breast and Cervical Cancer program reduced to 100% FPL (fewer than 50 individuals). Aged & Disabled (-): Income level for Employed Persons with Disabilities program reduced to 100% FPL (163 individuals). |

TABLE 3: CORRECTIONS-RELATED ENROLLMENT POLICIES IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, FY 2017 AND FY 2018

| States | Medicaid Coverage For Inpatient Care Provided to Incarcerated Individuals | Medicaid Outreach/Assistance Strategies to Facilitate Enrollment Prior to Release* | Medicaid Eligibility Suspended Rather Than Terminated For Enrollees Who Become Incarcerated* | |||||||||

| Jails | Prisons | Jails | Prisons | Jails | Prisons | |||||||

| In place FY 2017 | New or Expanded FY 2018 | In place FY 2017 | New or Expanded FY 2018 | In place FY 2017 | New or Expanded FY 2018 | In place FY 2017 | New or Expanded FY 2018 | In place FY 2017 | New or Expanded FY 2018 | In place FY 2017 | New or Expanded FY 2018 | |

| Alabama | X* | X* | X* | X* | X* | X* | ||||||

| Alaska | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | ||||||

| DC | X | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Florida | X | X | ||||||||||

| Georgia | X | X | ||||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | ||||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Kansas | X | X | ||||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| North Carolina | X | X | ||||||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Oklahoma | X | |||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||||

| Totals | 40 | 2 | 46 | 2 | 31 | 9 | 39 | 9 | 33 | 6 | 34 | 4 |

NOTES: ^States with “Medicaid outreach assistance strategies to facilitate enrollment prior to release” include those implementing a variety of strategies. In many cases, staff of the prison or jail provide most of the assistance in collaboration with the Medicaid agency. ^States that continue Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals but limit covered benefits to inpatient hospitalization are also included in the count of states that suspend eligibility. “*” indicates that a policy was newly adopted in FY 2018, meaning that the state did not have any policy in that category/column in place in FY 2017. N/A: The District of Columbia has jails but no prisons. However, DC is counted under Medicaid outreach/assistance strategies because some individuals who serve prison terms outside of DC may be placed in residential re-entry centers upon returning to DC and may apply for Medicaid to access coverage for 24-hour inpatient care and to facilitate enrollment prior to release.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2017. | ||||||||||||

Report: Managed Care Initiatives

Key Section Findings

Managed care is the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. Among the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 29 states reported that 75 percent or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2017. Because of nearly full MCO saturation in most MCO states, only a few states reported actions to increase MCO enrollment. Although many states still carve-out behavioral health services from MCO contracts, movement to carve-in these services continues. Nearly all states have managed care quality initiatives in place such as pay for performance or capitation withholds.–What to watch:

- Twenty-six of the 39 MCO states reported that they plan to use authority to receive federal matching funds for adults receiving inpatient psychiatric or substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in an institution for mental disease (IMD) for no more than 15 days a month included in the 2016 managed care regulations. Close to half of MCO states reported that the day limit is insufficient to meet acute inpatient or residential treatment needs for those with serious mental illness (SMI) or SUD.34

- States are using MCO arrangements to increase attention to the social determinants of health and to promote value-based payment. States are increasingly requiring MCOs to screen beneficiaries for social needs (19 states in FY 2017 and 2 additional states in FY 2018); to provide care coordination pre-release to incarcerated individuals (6 states in FY 2017 and 1 additional state in FY 2018); and to use alternative payment models (APMs) to reimburse providers (13 states in FY 2017 set a target percentage of MCO provider payments that must be in an APM and 9 additional states plan to set targets in FY 2018).

Tables 4 through 8 include more detail on the populations covered under managed care (Tables 4 and 5), behavioral health services covered under MCOs (Table 6), managed care quality initiatives (Table 7), and minimum Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) policies (Table 8).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a final rule on managed care in Medicaid and CHIP in April 2016. The new rule represents a major revision and modernization of federal regulations in this area.35 36 On June 30, 2017, CMS released an Informational Bulletin37 indicating they would use “enforcement discretion” to work with states on achieving compliance with the new managed care regulations, except for specific areas that “have significant federal fiscal implications.”

Managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 2017, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut,38 and Wyoming– had some form of managed care in place, unchanged from July 2016. The number of states contracting with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) (39 states) or operating a Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) program (16 states) as of July 2017 also remained unchanged from the prior year. PCCM is a managed fee-for-service (FFS) based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care.

Of the 48 states that operate some form of managed care, seven operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 32 states operate MCOs only and nine states operate PCCM programs only39 (Figure 2). Wyoming, one of the three states without any managed care (i.e., without either MCOs or a PCCM program), does operate a limited-benefit risk-based prepaid health plan (PHP). In total, 25 states (including Wyoming) contracted with one or more PHPs to provide Medicaid benefits including, behavioral health care, dental care, vision care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), or long-term services and supports (LTSS).

Populations Covered by Risk-Based Managed Care

The share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs or PCCM programs or remaining in FFS for their acute care varies widely by state. However, the share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs has steadily increased as states have expanded their managed care programs to new regions and new populations and made MCO enrollment mandatory for additional eligibility groups. This year’s survey showed continued modest growth. The survey asked states to indicate the approximate share of specific Medicaid populations who receive their acute care in MCOs, PCCM programs, and FFS. As shown in Figure 3, among the 39 states with MCOs, 29 states reported that 75 percent or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2017 (up from 28 states in last year’s survey), including four of the five states with the largest total Medicaid enrollment. These four states (California, New York, Texas, and Florida) account for nearly four out of every 10 Medicaid beneficiaries across the country (Figure 3 and Table 4).40

Consistent with past survey results, this year’s survey found that children and adults (particularly those enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion) are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly Medicaid beneficiaries or those with disabilities. Thirty-five of the 39 MCO states covered 75 percent or more of all children through MCOs. Twenty-eight of the 39 MCO states covered 75 percent or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g., parents, pregnant women) through MCOs. The elderly and people with disabilities were the group least likely to be covered through managed care contracts, with only 16 of the 39 MCO states covering 75 percent or more such enrollees through MCOs (Figure 3).

Of the 32 states that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2017, 27 were using MCOs to cover newly eligible adults. (The five Medicaid expansion states without risk-based managed care were Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Montana, and Vermont.) The large majority (24) of these 27 states covered more than 75 percent of beneficiaries in this group through risk-based managed care. New Hampshire, however, reported that approximately 80 percent of its ACA expansion adults receive premium assistance to enroll in Qualified Health Plans in the state’s Marketplace and that only 13.5 percent were enrolled in MCOs. The other two states reporting less than 75 percent MCO penetration for this group were Colorado and Illinois.

Seven of the 16 states with PCCM programs also contract with MCOs. In most of these states, MCOs cover a larger share of beneficiaries than PCCM programs. However, Colorado and North Dakota are exceptions. As of July 1, 2017, a majority of Colorado’s enrollees were in the PCCM program, which is the foundation of the state’s Accountable Care Collaboratives, and 40 percent of enrollees in North Dakota were enrolled in the PCCM program (compared to 25 percent in the MCO program).

Only two states reported policies implemented in FY 2017 or planned for FY 2018 that reduced or will reduce the states’ reliance on the MCO model of managed care: Colorado reported that a small MCO pilot initiated on July 1, 2016 terminated on June 30, 2017, and Massachusetts reported that the implementation of its Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program in FY 2018 will result in the transition of MCO enrollees to ACOs.

Populations with Special Needs

For geographic areas where MCOs operate, this year’s survey asked MCO states whether, as of July 1, 2017, certain subpopulations with special needs were enrolled in MCOs for their acute care services on a mandatory or voluntary basis or were always excluded. On the survey, states selected from “always mandatory,” “always voluntary,” “varies,” or “always excluded” for the following populations: pregnant women, foster children, persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/DD), children with special health care needs (CSHCNs), persons with a serious mental illness (SMI) or serious emotional disorder (SED), and adults with physical disabilities. This year’s survey found an increase in the number of states reporting that enrollment for these populations is always mandatory (Exhibit 2).

As shown in Exhibit 2 and Table 5, and consistent with results in last year’s survey, pregnant women were the group most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis while persons with ID/DD were least likely to be enrolled on mandatory basis and also most likely to be excluded from MCO enrollment. Foster children were the group most likely to be enrolled on a voluntary basis, although they were enrolled on a mandatory basis in a larger number of states. Among states indicating that the enrollment approach for a given group or groups varied, LTSS eligibility was the most frequently cited basis of variation.

| Exhibit 2: MCO Enrollment of Populations with Special Needs, July 1, 2017 (# of States) | ||||||

| Pregnant women | Foster children | Persons with ID/DD | CSHCNs | Persons with SMI/SED | Adults w/ physical disabilities | |

| Always mandatory41 | 32 | 20 | 11 | 20 | 18 | 19 |

| Always voluntary | 2 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Varies | 4 | 8 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 11 |

| Always excluded | 1 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

Acute Care Managed Care Population Changes

In both FY 2017 and FY 2018, only a few states reported actions to increase enrollment in acute care managed care, reflecting full or nearly full MCO saturation in most MCO states. Of the 39 states with MCOs, a total of 14 states indicated that they made specific policy changes in either FY 2017 (7 states) or FY 2018 (8 states) to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs through geographic expansion, voluntary or mandatory enrollment of new groups into MCOs, or mandatory enrollment of specific eligibility groups that were formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis (Exhibit 3). Thirty-six states reported that acute care MCOs were operating statewide as of July 2017 and Illinois reported plans to expand MCOs statewide in FY 2018. The remaining two states without statewide MCO programs (Colorado and Nevada) did not report a geographic expansion planned for FY 2018.

| Exhibit 3: Medicaid Acute Care Managed Care Population Expansions, FY 2017 and FY 2018 | ||

| FY 2017 | FY 2018 | |

| Geographic Expansions | MO | IL |

| New Population Groups Added | LA, NE, OH, TX, WV | IL, NY, PA, TX |

| Voluntary to Mandatory Enrollment | WA | NY, OR, SC, VA, WI |

Some of the notable acute care MCO expansions include:

- West Virginia transitioned its SSI population from FFS to mandatory MCO enrollment in July 2016.

- Missouri extended its MCO program geographically statewide on May 1, 2017 for children, pregnant women, refugees, and custodial parents.

- In January 2018, Pennsylvania will begin to phase-in its Community HealthChoices program which will provide both physical health and long-term services and supports through newly contracted MCOs. CHC enrollees will include individuals in nursing facilities (currently carved out of managed care after 30 days), full benefit dually-eligible individuals, and individuals receiving home and community-based services.

In FY 2017 and FY 2018, states expanded MCO enrollment (either voluntary or mandatory) to additional groups. Some states added multiple groups. Some groups that states added or are planning to add include: foster care or adoption assistance children (New York, Ohio, and Texas); persons eligible for LTSS (Nebraska, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas); ACA expansion, newly eligible adult group and enrollees in the state’s Health Insurance Premium Payment Program (Louisiana); Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program group (Ohio and Texas); children with special health care needs or SSI (Illinois, Ohio, and Texas); SSI population (West Virginia); and persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Nebraska and Ohio).

One state in FY 2017 and five in FY 2018 made enrollment mandatory for a specific eligibility group that was formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis: Washington (clients with Third Party Liability (TPL)/other insurance, excluding Medicare); New York (children with special health care needs in 1915(c) waiver programs); Oregon (Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibles); South Carolina (former foster care adults); Virginia (aged, blind, and disabled enrollees); and Wisconsin (SSI adults that do not have LTSS needs).

Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Behavioral Health Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Although MCOs are at risk financially for providing a comprehensive set of acute care services, nearly all states exclude or “carve-out” certain services from their MCO contracts, most commonly behavioral health services. In this year’s survey, states with acute care MCOs were asked to indicate whether specialty outpatient mental health (MH) services, inpatient mental health services, and outpatient and inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) services are always carved-in (i.e., virtually all services are covered by the MCO), always carved-out (to PHP or FFS), or carve-in status varies by geographic or other factors.

For purposes of this survey, “specialty outpatient mental health” services mean services used by adults with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) and/or youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED), commonly provided by specialty providers such as community mental health centers. Depending on the service, more than half of the 39 MCO states reported that specific behavioral health service types were carved into their MCO contracts, with specialty outpatient mental health services somewhat less likely to be carved in (Exhibit 4 and Table 6). Also, with the exception of inpatient SUD services, the number of states reporting that the other services were always carved-in increased modestly from last year.

| Exhibit 4: MCO Coverage of Behavioral Health, July 1, 2017 (# of States) | ||||

| Specialty Outpatient MH | Inpatient MH | Outpatient SUD | Inpatient SUD | |

| Always carved-in | 23 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Always carved-out | 11 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Varies | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

States reporting actions in FY 2017 to carve in behavioral health services into their MCO contracts (in at least some regions/contracts) included six states (Minnesota, Nebraska, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington). In FY 2018, ten states (Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, South Carolina, Washington, and West Virginia) report new/continued actions to carve in behavioral health services.

Institutions for Mental Diseases (IMD) Rule Change

The 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule42 allows states (under the authority for health plans to cover services “in lieu of” those available under the Medicaid state plan), to receive federal matching funds for capitation payments on behalf of adults who receive inpatient psychiatric or substance use disorder treatment or crisis residential services in an IMD for no more than 15 days in a month.43 States were asked in the survey whether they planned to use this new authority. Of the 39 states with MCOs, 26 states answered “yes” for FY 2017, FY 2018, or both FYs 2017 and 2018, five states answered “no,” and eight states answered “undetermined.”

States were also asked whether they believed the Final Rule allows MCOs sufficient flexibility to provide cost-effective “in lieu of” IMD services to meet acute inpatient or residential treatment needs for members with severe mental illness (SMI) or substance use disorders (SUDs). Only a small number of states (9 for SMI and 8 for SUD) answered “yes.” The remaining MCO states answered “no” (19 for SMI and 19 for SUD) or “don’t know” (11 for SMI and 12 for SUD). Many states commented that the 15-day limit was too restrictive, especially for SUD services, and a number of states indicated plans to seek a Section 1115 waiver to cover more than 15 days per month.44

Additional Services

States with MCO contracts reported that plans in their states may offer a range of services beyond those described in the state plan or waivers. Eleven states reported that MCOs provide limited or enhanced adult dental services beyond contractually required state plan benefits, and nine states reported enhanced vision services for adults. Several states noted that MCOs offer cell phones for reminder services or other technology supports from scales to telemedicine. Half of MCO states reported that MCOs provide a wide variety of non-clinical supports as value added services, including infant car seats and cribs, nominal gift cards for healthy behavior, air conditioners for asthma treatment, weight management classes or memberships, and even support for obtaining a GED. Health education, wellness supports, and non-traditional therapies were also noted by some states.

Managed Care (Acute and LTSS) Quality, Contract Requirements, and Administration

Quality Initiatives

Over time, the expansion of comprehensive risk-based managed care in Medicaid has been accompanied by greater attention to measuring quality and plan performance and, increasingly, to measuring health outcomes. After years of comprehensive risk-based managed care experience within the Medicaid program, many states now incorporate quality into the procurement process, as well as into ongoing program monitoring.

States procure MCO contracts using different approaches; however, most states use competitive bidding, in part because the dollar value is so large. Under these procurements, states can specify requirements and criteria that go beyond price, and may expect plans to compete on the basis of value-based payment arrangements with network providers, specific policy priorities such as improving birth outcomes, or strategies to address social determinants of health, and/or other specific performance and quality criteria. In this year’s survey, states were asked if they used, or planned to use, National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA’s) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) scores as criteria for selecting MCOs. Of the 39 states with MCOs, 18 indicated that they used or plan to use HEDIS scores as criteria for selecting MCOs.

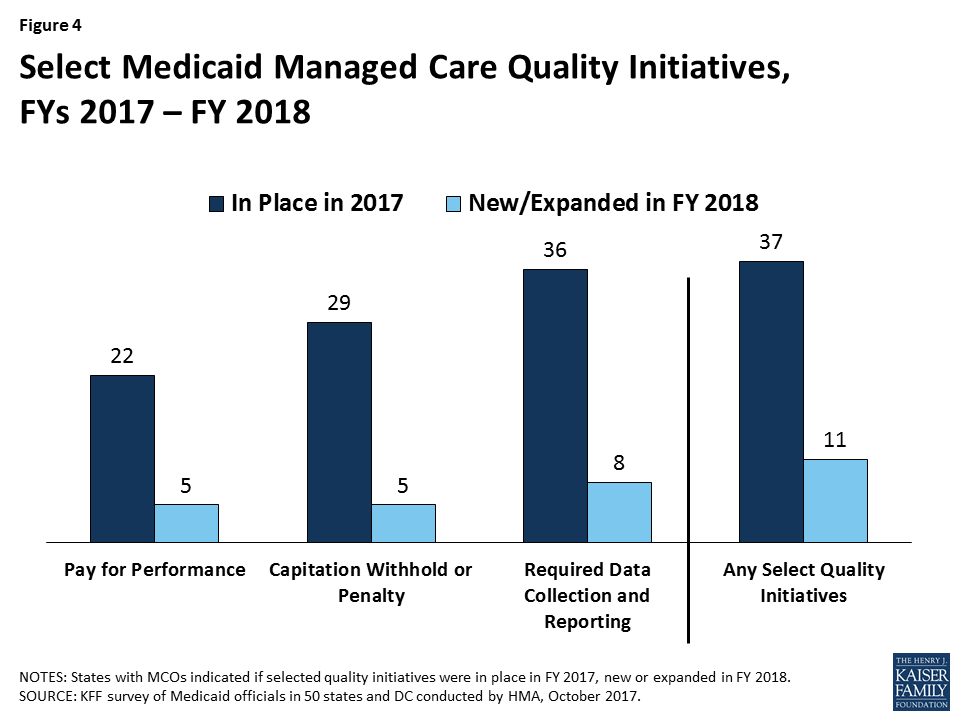

States were asked to indicate whether they had select quality strategies in place in FY 2017 and to indicate newly added or expanded initiatives for FY 2018. Thirty-seven MCO states reported one or more select MCO quality initiatives in place in FY 2017 (Figure 4 and Table 7). The most common strategies were requirements for data collection and reporting (often public reporting) on quality measures and the use of quality-based capitation withholds or penalties. Withhold amounts for acute care services typically ranged from 1 percent (Michigan, Oregon, and Washington) to 5 percent (Minnesota and Missouri); managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) withhold amounts typically ranged from 0.5 percent (Iowa and Wisconsin) to 3 percent (California and Ohio). Over half the 39 states with managed care contracts reported the use of pay for performance strategies. In addition, several states reported “other” quality initiatives, including the use of liquidated damages for poor performance and the required operation of and reporting on performance improvement projects (PIPs).

In FY 2018, 11 states expect to implement new or expanded quality initiatives (Figure 4). The most common new quality initiatives are pay for performance initiatives while the most common expanded initiatives are data collection and reporting initiatives (Table 7).

Contract Requirements

Alternative [Provider] Payment Models within MCO Contracts

Value-based purchasing (VBP) strategies are important tools for states pursuing improved quality and outcomes and reduced costs of care within Medicaid and across payers. Generally speaking, VBP strategies include activities that hold a provider or MCO accountable for cost and quality of care.45 This often includes efforts to implement alternative payment models (APMs). APMs replace FFS/volume-driven provider payments with payment models that incentivize quality, coordination, and value (e.g., shared savings/shared risk arrangements and episode-based payments). Many states have included a focus on adopting and promoting APMs as part of their federally supported State Innovation Models (SIM) projects and as part of delivery system reform efforts approved under Section 1115 Medicaid waivers.46 States are increasingly encouraging or requiring Medicaid MCOs to adopt APMs to advance VBP in Medicaid. The survey found that:

- Thirteen states (Arizona, California, Delaware, Hawaii, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Washington) identified a specific target in their MCO contracts for the percentage of provider payments, network providers, or plan members that plans must cover via alternative provider payment models in FY 2017 (compared to five states in FY 2016); and

- Nine additional states (District of Columbia, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, Oregon, Texas, and West Virginia) will include a target percentage in their contracts for FY 2018.

State APM Targets for Medicaid MCOs

- California’s Medi-Cal 2020 Waiver includes a requirement that MCOs must have VBP arrangements for 50-60 percent of all managed care lives assigned to receive care through a Designated Public Hospital participating in the PRIME program.47

- Delaware will require that 80 percent of all MCO members receive services from a provider under an alternative payment model by 2019.

- Iowa has a target of 40 percent for the share of an MCO’s membership to be covered by a VBP arrangement by FY 2018 and requires use of a common quality measurement tool.

- Washington requires MCOs to negotiate value-based contracts for at least 30 percent of capitated payments in FY 2017.

Further, in FY 2017, eight states had contracts that required Medicaid MCOs to adopt specific alternative provider payment models (e.g., episode of care payments, shared savings/shared risk, etc.), while eight states had contracts that encouraged MCOs to adopt specific APMs. In FY 2018, four additional states plan to require the use of specific APMs while five additional states plan to encourage use of specific APMs. The box below provides state examples of APM requirements.

State-Specific APM Requirements

- Minnesota MCOs are required to participate in the state’s ACO program, known as the Integrated Health Partnership. MCOs and the state share risk (gains and losses).

- Ohio requires MCOs to participate in Ohio’s retrospective episode-based payment model (with both positive and negative incentive payments) and the Ohio Comprehensive Primary Care program, Ohio’s patient-centered medical home (PCMH) program (with prospective, quarterly per-member per-month (PMPM) payments as well as retrospective total cost of care shared savings).

- Pennsylvania requires MCOs to make PCMH payments.

Social Determinants of Health

In April 2017, the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation selected 32 organizations to implement and test models to support local communities in addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, aiming to bridge the gap between clinical and community service providers. This “Accountable Health Communities” model represents the first CMS innovation model that focuses on social determinants of health. The goal of the five-year program is to encourage innovation to deliver local solutions that improve access to community-based services.48 This development reflects growing awareness and interest on the part of CMS to address other issues, such as housing and food insecurity, by linking beneficiaries to social services and supports, ultimately to improve health and health outcomes. States have also focused on addressing social determinants of health, so federal and state activity are occurring simultaneously.

The survey found that, of the 39 MCO states, 19 states required while 12 states encouraged MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs and provide referrals to other services in FY 2017. Two additional states plan to require and two plan to encourage MCOs to screen/refer enrollees for social needs in FY 2018.

Strategies to Address Social Determinants of Health

- Arizona requires coordination of community resources like housing and utility assistance under its MLTSS contract. The state provides state-only funding in conjunction with its managed behavioral health contract to provide housing assistance. The state also encourages health plans to coordinate with the Veterans’ Administration and other programs to meet members’ social support needs.

- The District of Columbia encourages MCOs to refer beneficiaries with three or more chronic conditions to the “My Health GPS” Health Home program for care coordination and case management services, including a biopsychosocial needs assessment and referral to community and social support services.

- Louisiana requires screening for problem gaming and tobacco usage and requires referrals to Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and the Louisiana Permanent Supportive Housing program when appropriate.

- Nebraska requires MCOs to have staff trained on social determinants of health and be familiar with community resources; plans are also required to have policies to address members with multiple biopsychosocial needs.

- New Jersey requires MLTSS plans to have a dedicated housing specialist and to provide assistance with attaining or maintaining housing as an “in lieu of” service.

Criminal Justice-Involved Populations

Engaging Medicaid MCOs in efforts to improve continuity of care for individuals released from correctional facilities into the community is important to ensure that individuals with complex or chronic health conditions, including behavioral health needs, have an effective transition to treatment in the community. In FY 2017, of the 39 states that contract with MCOs, six states (Arizona, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Ohio, and Virginia) require MCOs to provide care coordination services to enrollees prior to release from incarceration, while two states (Kentucky and New Mexico) encourage MCOs to provide care coordination services prior to release. Five states intend to use contracts to encourage or require such care coordination in FY 2018. The following are examples of pre-release state requirements: Louisiana requires plans to offer care management at least 30 days prior to scheduled release; Kansas requires pre-release care management for LTSS populations, and new legislation in Washington will require care coordination pre-release and post-incarceration in FY 2018. New Mexico, a state that encourages but does not require pre-release activity, reported that one health plan is piloting a care coordination model through collaboration with a metropolitan detention center to test and learn effective methods to impact recidivism and improve public health and safety.

Administrative Policies

Minimum Medical Loss Ratios

The Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) is the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement. CMS published a final rule in 2016 that requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid to achieve an MLR of at least 85 percent in the rate year, for rating periods and contracts starting on or after July 1, 2017.49 This 85 percent minimum MLR is the same standard that applies in Medicare Advantage and private large group plans. There is no federal requirement that Medicaid plans must pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard, but states have discretion to require remittances.

As of July 1, 2017, 25 of the 39 states that contract with comprehensive risk-based MCOs specified a minimum MLR in Medicaid MCO contracts. Twenty of these 25 states applied the MLR requirement to all MCO contracts, while five states applied it on a limited basis. Seventeen of the 25 states with minimum MLR requirements always require remittance payments to the state if the minimum MLR is not achieved; one state (Ohio) requires remittance under some circumstances.50

Medicaid MLRs vary by state but are most commonly set at 85 percent or higher. A few states noted that their minimum MLRs varied by type of plan or population. For example, in New Jersey, the MLR is calculated separately for each population covered, with an MLR of 85 percent set for acute care contracts and an MLR of 90 percent set for MLTSS contracts.

Table 8 provides state-specific information regarding the use of a minimum MLR.

Auto-Enrollment

Generally, beneficiaries who are required to enroll in MCOs must be offered a choice of at least two plans. Those who do not select a plan are auto-enrolled in a plan by the state. The proportion of MCO beneficiaries who are auto-enrolled varies widely across states. State auto-enrollment algorithms also vary, but usually take into consideration variables like previous plan or provider relationships, beneficiary geographic location, and/or plan enrollments of other family members. States may also aim to balance enrollment among plans. As of July 1, 2017, 11 states took plan quality or performance rankings into consideration in the auto-enrollment algorithm (Arizona, California, Hawaii, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington).

PCCM and PHP Program Changes

Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) Program Changes

Of the 16 states with PCCM programs, two reported enacting policies to increase PCCM enrollment in FY 2017 or FY 2018: Colorado reported continued growth in its PCCM-based Accountable Care Collaboratives in both FY 2017 and FY 2018, and Arkansas reported implementing new billing software that would auto-assign beneficiaries to a primary care physician. Two other states reported new PCCM programs: Alaska – one of only three states without either an MCO or PCCM program as of July 1, 2017 – reported plans to implement a PCCM program in FY 2018, and Arizona reported plans to implement an American Indian Medical Home effective October 1, 2017 using PCCM authority.

Three states51 (California, Illinois, and Massachusetts) reported actions to decrease enrollment in a PCCM program in FY 2017 or FY 2018. California plans to transition its one-county HIV PCCM program to a full-risk MCO model in CY 2018; Illinois reported that its Integrated Health Homes would move to managed care under new MCO contracts that would begin in FY 2018, and Massachusetts reported that implementation of its Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program in FY 2018 will include the transition of PCCM members to ACO Plans.

Limited-Benefit Prepaid Health Plans (PHP) Changes

In this year’s survey, the 25 states contracting with at least one PHP as of July 1, 2017, were asked to indicate whether certain services (listed in Exhibit 5 below) were provided under these arrangements. The most frequently cited services provided (of those included in the question) were outpatient mental health services (14 states), followed by non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) (12 states) and inpatient mental health and outpatient substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services (11 states each).

| Exhibit 5: Services Covered Under PHP Contracts, July 1, 2017 | ||

| # of States | States52 | |

| Outpatient Mental Health | 14 | CA, CO, HI, ID, MA, MI, NC, OR, PA, TN, UT, WA, WI, WY |

| Inpatient Mental Health | 11 | CA, CO, HI, MA, MI, NC, PA, TN, UT, WA, WI |

| Outpatient Substance Use Disorder Treatment | 11 | CO, ID, MA, MI, NC, OR, PA, TN, UT, WA, WI |

| Inpatient Substance Use Disorder Treatment | 9 | CO, MA, MI, NC, PA, TN, UT, WA, WI |

| Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT) | 12 | FL, IA, KY, ME, MI, NJ, OK, RI, TN, TX, UT, WI |

| Dental | 9 | CA, IA, ID, LA, MI, RI, TN, TX, UT |

| Long-Term Services and Supports | 6 | ID, MI, NC, NY, TN, WI |

| Vision | 1 | TN |

Nine states reported implementing policies to increase PHP enrollment in FY 2017 or FY 2018. Five states (Arkansas, Iowa, Idaho, Nebraska, and Nevada) reported new or expanded dental PHPs in FY 2018, Indiana reported plans for an NEMT PHP contract in FY 2018, California reported adding inpatient SUD treatment to its PHP program in FY 2018, Louisiana will add “Coordinated System of Care” PHPs in FY 2018 (serving youth with behavioral health challenges and their families), and New York reported increased enrollment in its LTSS PHPs in both FY 2017 an FY 2018.

Four states also reported actions to decrease PHP enrollment in FY 2017 or FY 2018. Nebraska and Texas reported ending a behavioral health PHP and folding the covered services into MCO contracts in FY 2017. Washington reported that PHP enrollment decreased in FY 2017 and will decrease further in FY 2018 when the state converts behavioral health PHPs to fully integrated MCO contracts in additional geographic areas. Massachusetts reported that implementation of its Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program in FY 2018 will reduce enrollments in its behavioral health PHP program.

TABLE 4: SHARE OF THE MEDICAID POPULATION COVERED UNDER DIFFERENT DELIVERY SYSTEMS IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, AS OF JULY 1, 2017

| States | Type(s) of Managed Care In Place | Share of Medicaid Population in Different Managed Care Systems | ||

| MCO | PCCM | FFS / Other | ||

| Alabama | PCCM | — | 86.4% | 13.6% |

| Alaska | FFS | — | — | 100.0% |

| Arizona | MCO | 93.1% | — | 6.9% |

| Arkansas* | PCCM | — | NR | NR |

| California | MCO and PCCM* | 78.9% | — | 21.1% |

| Colorado | MCO and PCCM* | 10.5% | 72.6% | 16.9% |

| Connecticut | FFS* | — | — | 100.0% |

| DC | MCO | 78.0% | — | 22.0% |

| Delaware | MCO | 94.2% | — | 5.8% |

| Florida | MCO | 92.0% | — | 8.0% |

| Georgia | MCO | 73.0% | — | 27.0% |

| Hawaii | MCO | 99.9% | — | <0.1% |

| Idaho* | PCCM | — | 95.0% | 5.0% |

| Illinois | MCO and PCCM | 63.4% | 10.4% | 26.2% |

| Indiana | MCO | 80.0% | — | 20.0% |

| Iowa | MCO | 92.6% | — | 7.4% |