Medicaid Managed Care Plans and Access to Care: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation 2017 Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans

Provider Payment and Delivery System Reform

There is great interest among public and private payers alike in restructuring delivery systems to be more integrated and patient-centered, along with developing concomitant initiatives to adjust provider payment models to incentivize quality. Payment reforms often include “alternative payment models” (APMs). APMs lie along on a continuum, ranging from arrangements that involve limited or no provider financial risk (e.g., pay-for-performance (P4P) models) to arrangements that place providers at more financial risk (e.g., shared savings/risk arrangements or global capitation payments). APMs often go hand-in-hand with delivery system reform initiatives, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), ACA Health Homes, and physical and behavioral health integration activities. (See Appendix Box 1 for definitions of common payment and delivery system reform models.) States may encourage or require Medicaid MCOs to implement specific delivery system and/or payment reform initiatives. Alternatively, MCOs themselves may design and implement delivery system and payment reform initiatives. As of FY 2017, more than half of the 39 states that contract with comprehensive risk-based MCOs require (13 states) or plan to require in FY 2018 (9 states) that MCOs make a target percentage of provider payments through APMs.1 Fewer states require (8 states) or plan to require (4 states) that Medicaid MCOs adopt specific APMs (e.g., episodes of care, shared savings/shared risk etc.).2

Almost all plan respondents (93%) still make fee-for-service (FFS) payments to at least some providers, but most are paying at least some primary care providers (PCPs) through methods other than FFS (such as salary, prospective payment, or capitation), and many also pay at least some specialists through non-FFS methods. Within Medicaid, states pay Medicaid MCOs per-member-per-month capitation payments for Medicaid enrollees; however, plans generally have wide latitude to determine how to pay their contracted providers. Medicaid MCOs may pay the providers in their networks on a FFS basis, capitation basis, or on other terms. Sixty-three percent of plans reported using a method other than FFS to pay at least some PCPs, while only 44% of plans reported using a method other than FFS to pay at least some specialists.

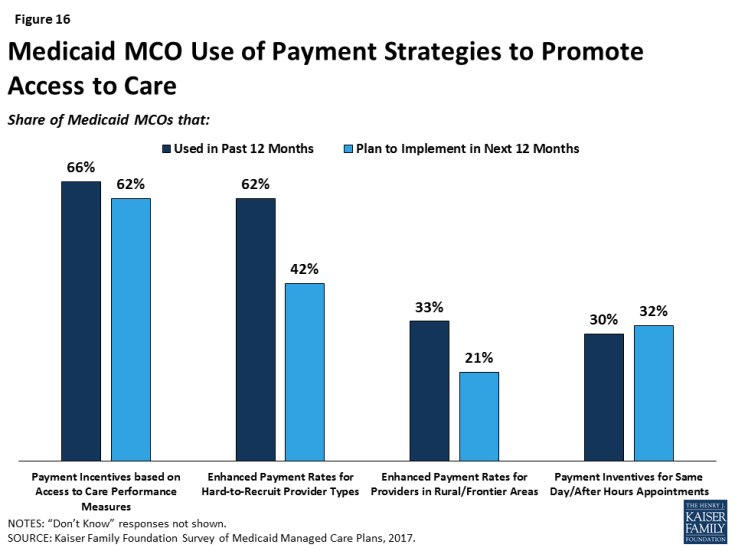

Plans are using provider payment as a policy lever to facilitate access to care. Two-thirds of plans in the survey reported that they currently use payment incentives related to access to care (Figure 16), and about an equal share plan to implement new or additional access-related payment incentives in the upcoming year. About a third of plans reported using payment incentives for providers to have same-day or after-hours appointments. A majority of plans (67%) said that they either already use (62%) or plan to use (42%) enhanced payment rates for hard-to-recruit provider types, and 34% reported using (33%) or planning to use (21%) enhanced payment for providers in rural or frontier areas.

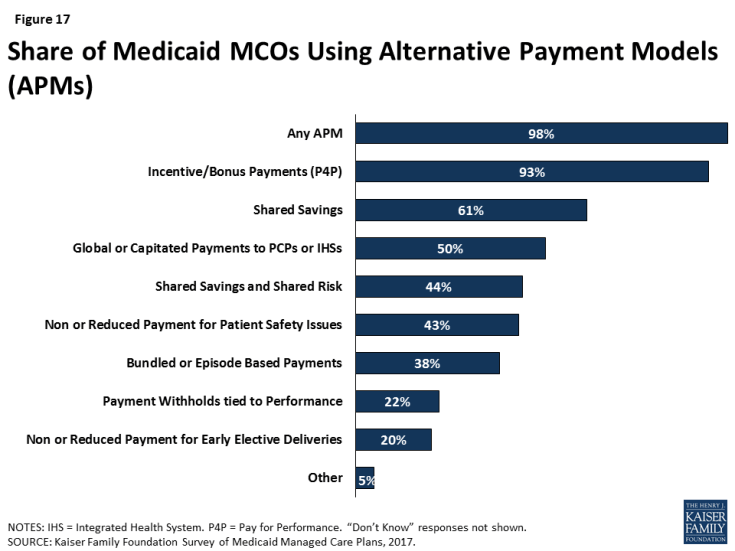

While most plans have continued paying providers through the traditional FFS method, nearly all plans have also adopted new systems of payment by using APMs to reward providers for meeting quality and, in some cases, cost-based benchmarks. These approaches are not mutually exclusive, as APMs can build on FFS payment, and multiple APMs can be utilized simultaneously. Ninety-eight percent of plans in the survey reported using at least one APM for at least some providers (Figure 17). The vast majority of plans (93%) reported using incentives and/or bonus payments tied to specific performance measures (so-called “pay-for-performance”), which involve limited or no provider financial risk. Fewer plans reported using APMs that typically transfer more risk to providers, such as bundled or episode-based payments (38%) and shared savings and risk arrangements (44%), which may be more resource-intensive to design and implement.

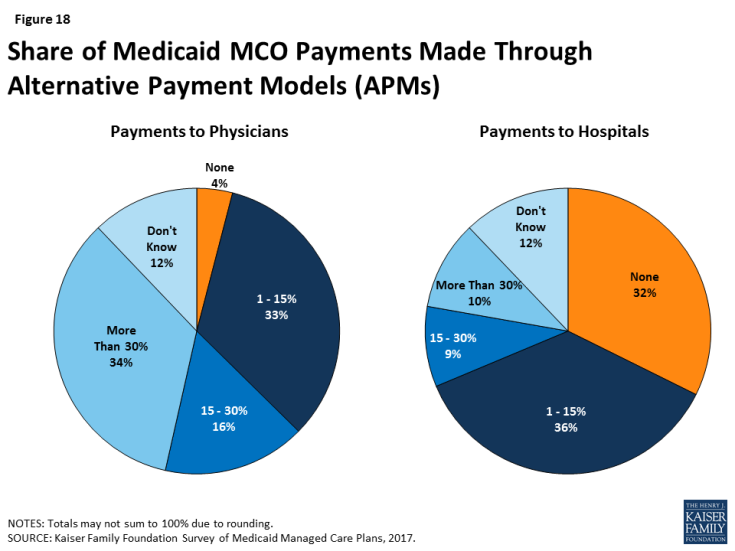

Although nearly all plans report using at least one APM, the overall share of payments made to providers through APMs is modest, especially for hospital payment (Figure 18). Plans may pay any type of provider through an APM. When asked about use of APMs among PCPs and hospitals, responding plans reported that they were less likely to use APMs for hospitals than for PCPs. Nearly a third of plans (32%) said that they make no payments through APMs to hospitals, while few plans (4%) reported making no APM payments to PCPs.3 While a similar share of plans reported making between 1% and 15% of payments through APMs to PCPs (33%) and hospitals (36%), more than a third of plans (34%) reported making more than 30% of payments to PCPs through APMs, while just 10% of plans reported making more than 30% of payments to hospitals through APMs.

Plans also reported interest in delivery system models that build on new payment models, such as ACOs and PCMHs. Both ACOs and PCMHs aim to create patient-centered and coordinated care delivery systems (see Box 1 for definitions) by increasing provider responsibility for quality, efficiency, and patient outcomes. Twenty-eight percent of plans in the survey reported contracting with an ACO, and roughly one-third of remaining plans are considering contracting with ACOs in the future.4 Not surprisingly, plans contracting with ACOs are more likely than plans overall (89% versus 73%) to be using shared savings and/or shared savings and risk arrangements, which are a core feature of ACOs, and are more likely to make a larger share of payments to hospitals through APMs (41% making at least 15% of hospital payments through APMs versus 19% of all plans, data not shown). Additionally, about a third of plans that do not contract with ACOs reported using shared savings and/or shared risk arrangements. These plans may be using shared savings or shared risk payment models with other provider types and/or other delivery system reform efforts, including PCMH models. Overall, 69% of plans reported offering their beneficiaries enrollment in PCMHs.5 It is unclear how many members are covered by these new payment and delivery system arrangements. For example, while a majority of plans offer PCMH to their members, only 26% of plan respondents reported that at least half of their Medicaid members are served through such arrangements.

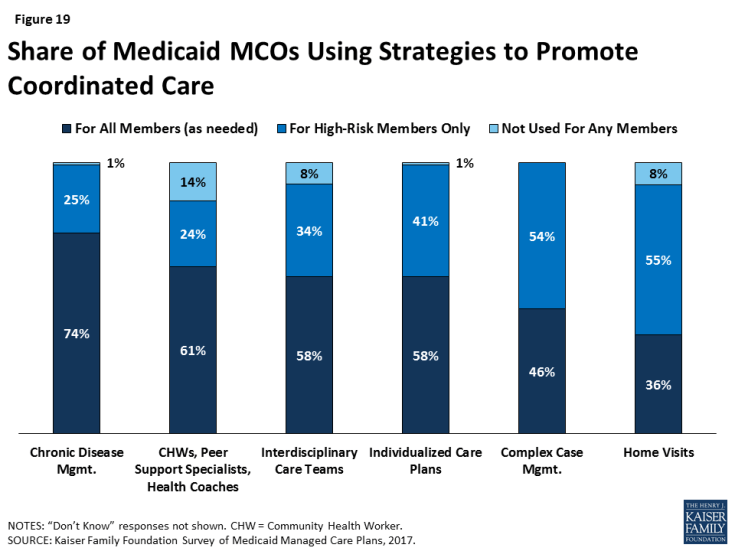

In addition to contracting with ACOs and PCMHs, plans are using a variety of other strategies to coordinate care for beneficiaries (Figure 19). Plans reported wide usage of these strategies, with most plans using chronic disease management, peer support or health coaches, interdisciplinary care teams, or individualized care plans for all members on an as-needed basis. Other strategies, such as complex case management and home visits, are more likely to be offered to high-risk members only (54% and 55% of plans, respectively). In their efforts to target high-risk members, plans also offer population-specific services (data not shown). For example, more than 80% of plans reported offering case management or care coordination to homeless individuals, and approximately three-quarters of respondents reported conducting outreach to members or potential members who are homeless to assist with health care access.

Plans are also active in promoting the integration of physical and behavioral health (Table 5). Integration of physical and behavioral health ranks as the top priority for health plans in ensuring access to care for members, with nearly half (49%) of respondents ranking it as a top three priority (Table 2). Nearly all plans (94%) reported at least one strategy to promote provider-level physical and behavioral health integration. Plans are currently more likely to pursue such integration through organizational/administrative methods, such as contracting with health systems with co-located providers (77%), offering provider training/education (64%), or facilitating medical record sharing (55%), than through payment strategies such as offering payment incentives for colocation of physical and behavioral health providers (28%) or for PCPs to screen or refer for behavioral health needs (26%). When asked about barriers to integration, no single issue was most commonly cited by plans; rather, plans gave a variety of answers for the greatest challenge to integration, indicating that such efforts may be unique to the specific circumstances and location of a plan.

| Table 5: Plan Activities to Integrate Physical and Behavioral Health Care | |

| Share of Plans Reporting | |

| Any strategy | 94% |

| Organizational/Administrative Strategies | |

| Establish care management/coordination teams with both physical and behavioral health providers | 85% |

| Contract with practices or health systems that provide co-located or integrated care | 77% |

| Offer provider training/education | 64% |

| Facilitate sharing of medical records | 55% |

| Operate or contract with Medicaid health homes for individuals with SMI and/or SUD | 46% |

| Other | 8% |

| None | 2% |

| Payment Strategies | |

| Payment incentives/financial support for co-location of physical and behavioral health providers | 28% |

| Payment incentives for PCPs to screen/refer for behavioral health needs | 26% |

| Payment incentives for behavioral health providers to screen/refer for chronic health care needs | 16% |

| Other | 8% |

| None | 45% |

| NOTES: SMI = Serious Mental Illness. SUD = Substance Use Disorder. Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. |

|