Medicaid Managed Care Plans and Access to Care: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation 2017 Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans

Provider Networks and Access to Care

Though research indicates that, overall, most primary care providers and specialists accept Medicaid,1 provider participation in Medicaid is a subject of much debate. Providers are less likely to accept new Medicaid patients than new patients insured by other payers,2 and lower participation rates among some types of specialists remain an area of concern. In addition to provider participation, provider supply shortages in a particular state or region (especially rural areas) can affect enrollee access to care, as only 11 states currently meet at least two-thirds of their residents’ need for health professionals.3 Plan efforts to recruit and maintain their provider networks can play a crucial role in determining enrollees’ access to care through factors such as travel times, wait times, or choice of provider.

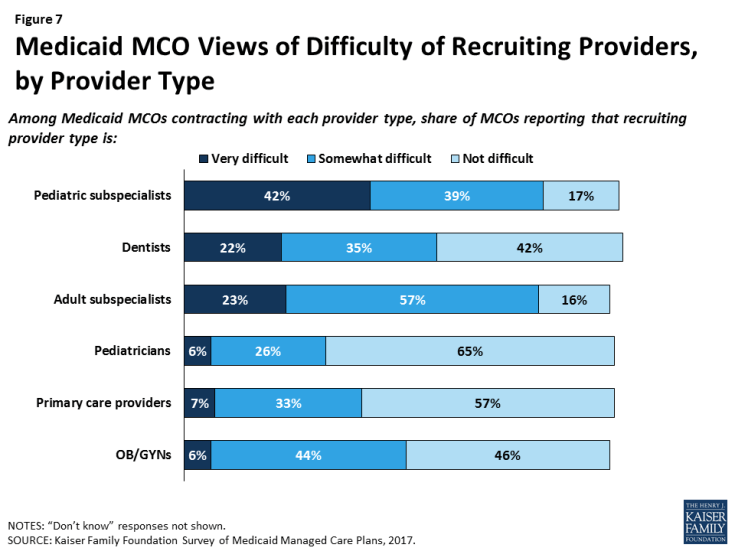

Plans report more challenges in recruiting specialty providers than primary care providers to their networks. Eight in ten plans that responded to the survey said that it is somewhat or very difficult to recruit adult (80%) or pediatric (81%) subspecialists to their networks, compared to 40% reporting such difficulty for primary care providers, 50% for obstetrician/gynecologists, and 32% for pediatricians (Figure 7). Among plans that contract with dentists, more than half reported difficulty in recruiting dentists.

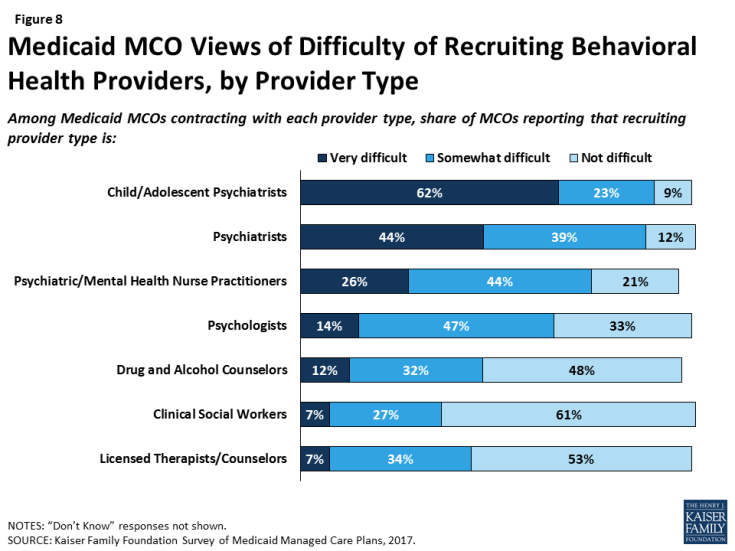

Plans also reported high rates of difficulty in recruiting physician behavioral health providers to their network. Specifically, 85% of responding plans that contract with child or adolescent psychiatrists reported difficulty in recruiting these providers, and 83% that contract with general psychiatrists reported difficulty in recruiting them (Figure 8). These findings align with broader challenges with recruiting psychiatrists that extend across all payers, as psychiatrists accept Medicaid, private insurance and Medicare at lower rates than other specialists.4 In the survey, plans reported less difficulty in recruiting non-physician behavioral health providers such as clinical social workers, licensed therapists, or drug and alcohol counselors.

Figure 8: Medicaid MCO Views of Difficulty of Recruiting Behavioral Health Providers, by Provider Type

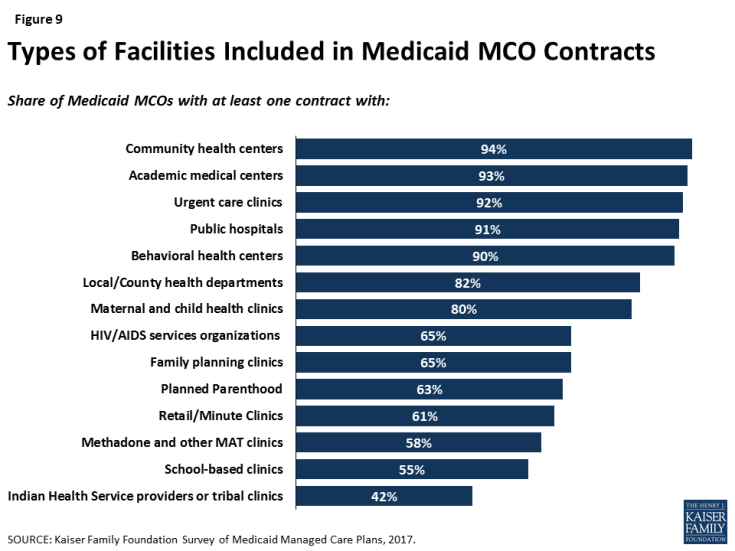

Similarly, plans reported contracting with a range of facility types, but some specialty facilities are less likely to be included in plan networks than general facilities. For example, at least nine out of ten responding plans reported contracting with general service facilities such as community health centers, academic medical centers, urgent care clinics, public hospitals, and behavioral health centers. Smaller shares — though still a majority — reported contracting with specialty facilities such as HIV/AIDS service organizations, family planning clinics or Planned Parenthood, or methadone clinics (Figure 9). While these differences may reflect plan focus or specialty to some extent, patterns remain similar when looking only at plans that provide a specialty service or serve a specialty population. For example, only two-thirds of plans that provide outpatient substance use disorder services reported contracting with methadone clinics and/or medication assistance treatment (MAT) facilities, and only 68% of plans that serve people with HIV/AIDS contract with HIV/AIDS service organizations (data not shown). It is not clear from survey results why certain facility types may not be included in plan networks; plans may exclude certain facilities or facilities may decline to contract with Medicaid MCOs.

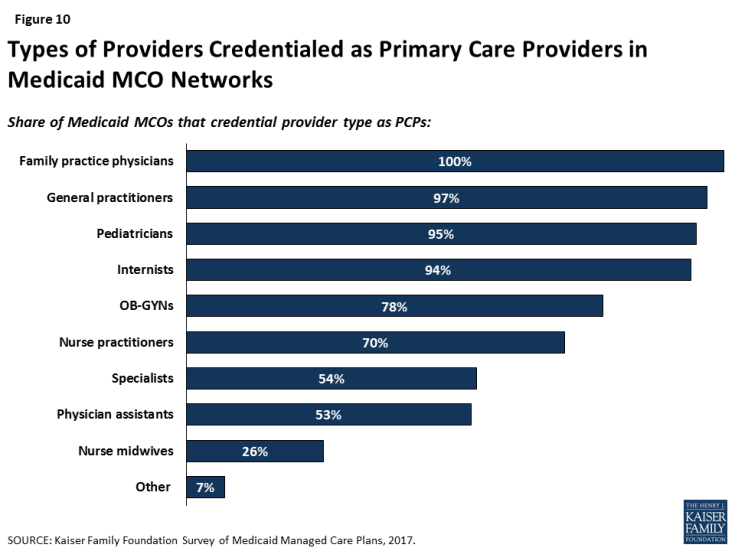

Perhaps reflecting state licensing rules, plans reported mixed use of physician extenders as primary care providers. Seven in ten plans that responded to the survey credential nurse practitioners as primary care providers, but fewer plans credential physician assistants (53%) or nurse midwives (26%) as primary care providers (Figure 10). These differences may reflect state laws about scope of practice guidelines or state Medicaid agency policy more than plan preferences. Research indicates that physician extenders may play an important role in meeting the need for primary care, particularly in areas with provider shortages. The Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) has projected a shortage of 20,400 primary care physicians in 2020, and nurse practitioners are more likely than primary care physicians to practice in underserved areas.5

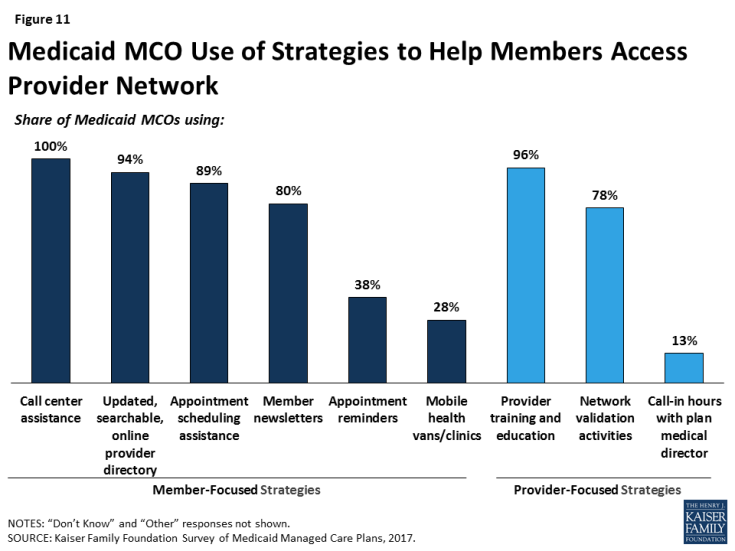

Proactive actions to identify gaps in network capacity are less common than ongoing monitoring. Currently, the most common activities plans that reported for monitoring network capacity are member/provider complaints or call center reports, feedback from regular member survey data such as CAHPS, or monitoring out-of-network visits (Table 1). Similarly, when asked about steps taken to help members access care from network providers, responding plans were more likely to report member-initiated efforts such as call center assistance (100%), searchable online directories (94%), or appointment scheduling assistance (89%) than plan-initiated strategies such as mobile vans (28%) or appointment reminders (38%) (Figure 11). Most plans also reported undertaking network validation activities and provider training.

| Table 1: Plan Activities to Monitor Network Capacity | |

| Strategy | Share of Plans Reporting |

| Member complaint and/or grievance reports | 88% |

| Provider complaints | 77% |

| CAHPS/member survey data | 72% |

| Out-of-network utilization monitoring | 67% |

| Call center reports | 56% |

| Site visits to provider offices | 53% |

| Secret shopper calls | 52% |

| Encounter data analysis to identify under-utilization | 49% |

| Emergency room utilization rate analysis | 47% |

| Inpatient admission/readmission rate analysis | 36% |

| Other | 17% |

| None | 1% |

| NOTES: CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. |

|

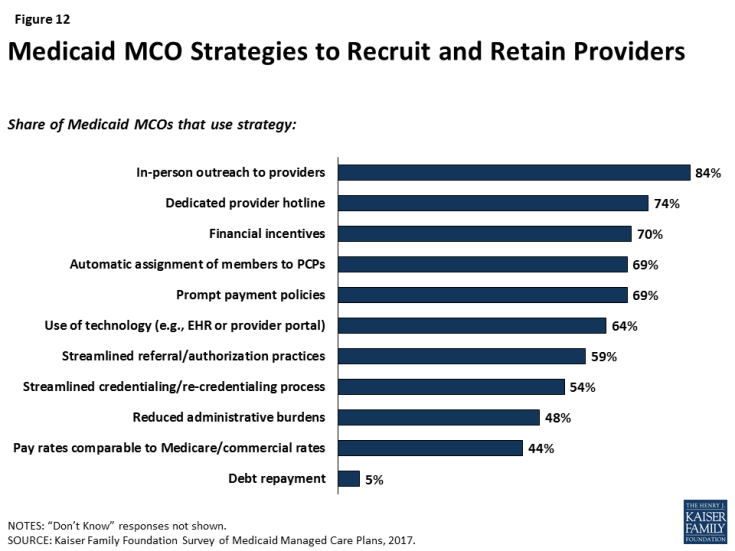

Responding plans reported a variety of strategies to address provider network issues. Among the strategies that plans use to recruit and retain providers, responding plans most frequently reported using direct outreach to providers (84%) and provider hotlines (74%), and more than half of responding plans reported using improved administrative actions (e.g., auto-assignment of enrollees, streamlined reporting or credentialing systems, or streamlined referral practices) to recruit and retain providers (Figure 12). Plans also reported using payment or financial strategies, such as sign-on bonuses (70%), prompt payment policies (69%), or payment rates comparable to Medicare or commercial insurance (44%), as incentives to recruit and retain providers. As discussed in more detail below, a majority of plans said that they either already use or plan to use enhanced payment rates for hard-to-recruit provider types, and about a third reported using or planning to use enhanced payment for providers in rural or frontier areas. Though it was not clear based on survey results whether plans are using payment levels more broadly as an incentive for provider participation, about four in ten plans reported that they directly negotiate rates with providers rather than set them based on existing Medicaid or Medicare fee schedules (data not shown).

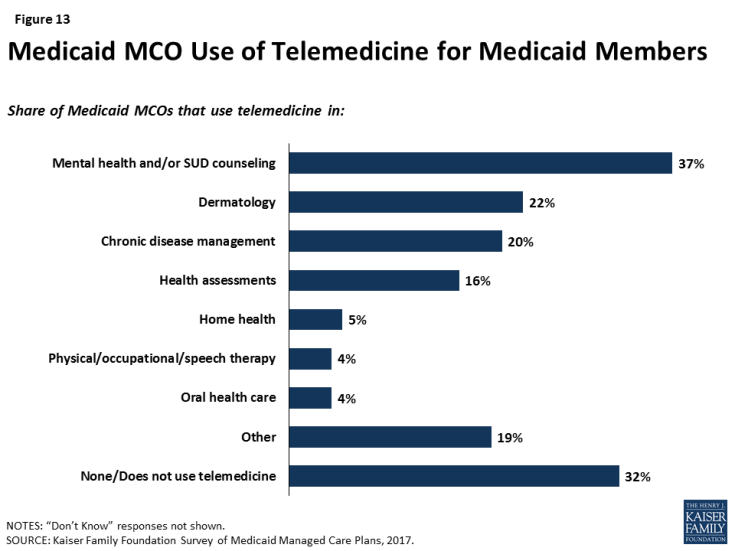

Another strategy to address network issues is the use of telemedicine. More than two-thirds (68%) of responding plans reported using telemedicine in at least one area (Figure 13), with plans most likely to use telemedicine in mental health or substance use disorder counseling. This focus could reflect particular difficulty in recruiting psychiatrists to plan networks. Under the 2016 managed care rule, CMS has noted that plans may use telemedicine to meet network adequacy requirements, though plans may be subject to state requirements related to the use of telehealth as well as state-defined (within federal parameters) network adequacy standards.6

The expansion of Medicaid under the ACA led to some concern about strains on provider capacity due to increased health coverage. Among responding plans operating in states that expanded Medicaid, more than seven in ten reported that they expanded their provider networks between January 2014 and December 2016 to serve the newly-eligible population. Plans were more likely to report adding primary care providers (59%) and specialists (56%) than mental health (48%) or substance use disorder treatment (35%) providers.7

Plans were more likely to cite provider supply shortages than low provider participation in Medicaid as a top challenge in ensuring access to care. When asked broadly about top challenges in ensuring access to care for members, provider issues were among the top issues ranked by plans (Table 2). However, plans responding to the survey were more than six times more likely to cite issues with provider supply than issues with provider participation in Medicaid, suggesting that challenges in recruitment and network adequacy are linked to broader market trends. Similarly, when asked about overall priorities, plans were much less likely to rank network-related activities (such as provider recruitment) than other issues.

| Table 2: Top Challenges and Priorities in Ensuring Access to Care | ||

| Share of Plans Reporting as One of Top Three | ||

| Challenges: | ||

| Provider supply shortages in certain specialties | 65% | |

| Provider supply shortages in certain geographic areas | 62% | |

| Capitation rate paid by the state is too low | 48% | |

| Lack of continuous eligibility for Medicaid members (i.e., “churn”) | 46% | |

| Member education about how to access care | 38% | |

| Caps on providers’ Medicaid patient panels | 11% | |

| Low physician participation in Medicaid | 10% | |

| Other | 11% | |

| Priorities: | ||

| Improve integration of physical and behavioral health | 49% | |

| Implement or expand intensive care management strategies for high-risk members | 43% | |

| Improve coordination with community-based social services organizations | 39% | |

| Improve Medicaid MCO data and information systems | 37% | |

| Implement new delivery models such as PCMHs | 26% | |

| Incentivize current network providers to accept more new Medicaid patients | 23% | |

| Contract with more mental health providers | 15% | |

| Contract with more primary care providers | 14% | |

| Contract with more specialists | 14% | |

| Expand use of non-physician providers | 13% | |

| Improve member education | 6% | |

| Contract with more substance use disorder providers | 5% | |

| Other | 10% | |

| NOTES: Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. |

||