Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2018: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Premiums and Cost Sharing

Given that Medicaid and CHIP enrollees have limited ability to pay out-of-pocket costs due to their modest incomes, federal rules establish parameters for premiums and cost sharing for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees (Box 2). Some states charge higher premiums for adults than otherwise allowed under federal rules through waivers, and additional states have proposed waivers to charge higher premiums and/or cost sharing.

| Box 2: Medicaid and CHIP Premium and Cost Sharing Rules |

| Premiums in Medicaid. States may charge premiums for children and adults with incomes above 150% FPL. Medicaid enrollees with incomes below 150% FPL may not be charged premiums.

Cost Sharing in Medicaid. States may charge cost sharing for adults in Medicaid, but allowable charges vary by income (Table 1). Cost sharing cannot be charged for emergency, family planning, pregnancy-related services in Medicaid, preventive services for children, or for preventive services in Alternative Benefit Plans in Medicaid, which have been defined as essential health benefits. In addition, children with incomes below 133% FPL generally cannot be charged cost sharing. Limit on Out-of-Pocket Costs. Overall, premium and cost sharing amounts for family members enrolled in Medicaid may not exceed 5% of household income. Premiums and Cost Sharing in CHIP. States have somewhat greater flexibility to charge premiums and cost sharing for children covered by CHIP, although there remain limits on the amounts that can be charged, including an overall cap of 5% of household income. |

| Table 1: Allowable Cost Sharing Amounts for Adults in Medicaid by Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 100% – 150% FPL | >150% FPL | |

| Outpatient Services | up to $4 | up to 10% of state cost | up to 20% of state cost |

| Non-Emergency use of ER | up to $8 | up to $8 | No limit |

| Prescription Drugs | Preferred: up to $4 Non-Preferred: up to $8 |

Preferred: up to $4 Non-Preferred: up to $8 |

Preferred: up to $4 Non-Preferred: up to 20% of state cost |

| Inpatient Services | up to $75 per stay | up to 10% of state cost | up to 20% of state cost |

Premiums and Cost Sharing for Children

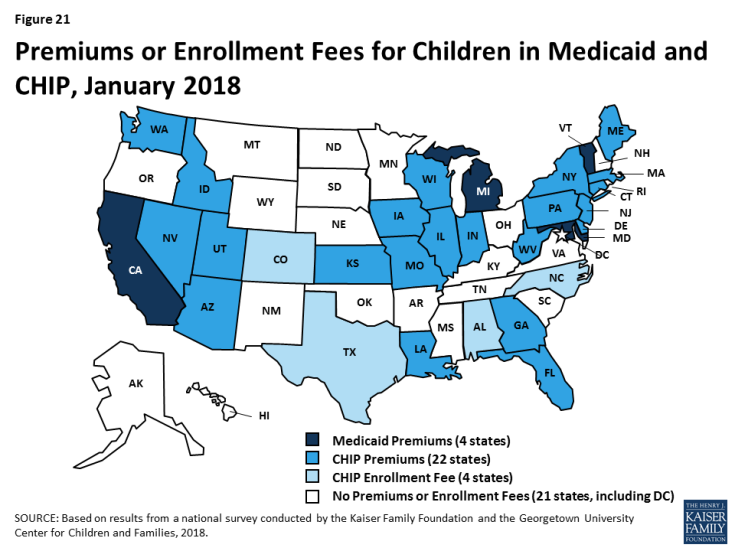

Some states have eliminated premiums for children since implementing the ACA, and the ACA protected children from premium increases. Prior to the ACA in 2013, five states charged premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid, and 30 of 38 states with separate CHIP programs charged premiums or enrollment fees. Under the ACA, states were required to move older children with incomes between 100%-138% FPL from CHIP to Medicaid, which does not allow premiums for children below 150% FPL. In eight states, children were no longer charged premiums due to this transition. The ACA MOE also protected children from new premiums or premium increases.1 Between 2013 and 2018, Minnesota and Rhode Island eliminated premiums for children in Medicaid, and Oregon eliminated premiums in CHIP. California, Michigan, and Vermont eliminated their separate CHIP programs and moved all children from CHIP to Medicaid, although they still charge premiums in Medicaid for higher-income children. Reflecting these changes, as of January 2018, four states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid, and 26 of 36 states with separate CHIP programs charge premiums or enrollment fees (Figure 21). Premiums begin for children with incomes between 133% and 150% in eight states, and for children with incomes at or above 150% FPL in 22 states. Of the total, 30 states that charge premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid and/or CHIP, 11 states charge premiums or fees that are family-based and 14 other states have a family maximum amount.

The ACA limited lockout periods in CHIP to minimize gaps in coverage for children. In Medicaid, states must provide enrollees a minimum 60-day grace period before cancelling coverage for non-payment of premiums, and states cannot delay re-enrollment or require enrollees to repay outstanding premiums as a condition of reenrollment. In contrast, CHIP programs must provide a minimum 30-day grace period and may impose a “lockout period” during which a child who has been disenrolled is not allowed to reenroll. Prior to the ACA, CHIP lockout periods ranged from one to six months in the 12 states that imposed them. The ACA limited lockout periods to no more than 90 days; 15 states have a lock out period in CHIP as of January 2018.

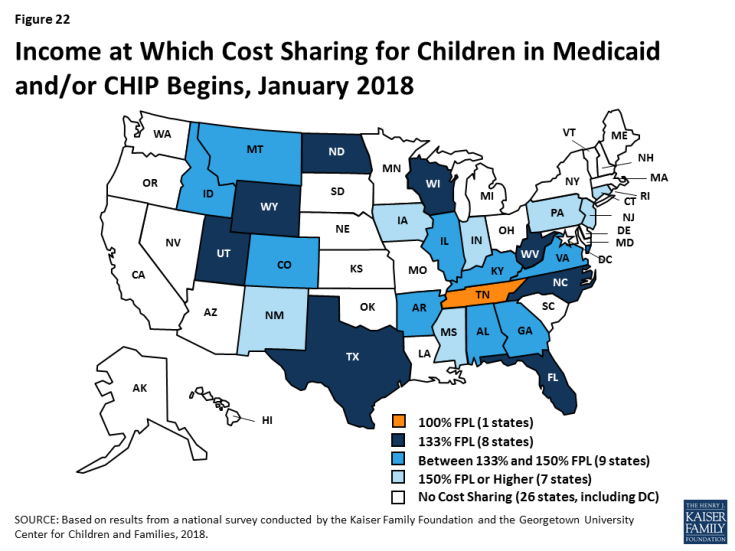

Cost sharing for children remains more prevalent in CHIP compared to Medicaid. Between 2013 and 2018, four states (California, Delaware, Louisiana and Oregon) eliminated copayments for children. As of 2018, three states charge cost sharing for children in Medicaid, and 24 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs charge cost sharing. In eight states, cost sharing begins at the federal minimum level of 133% FPL, while 16 states begin cost sharing at a higher income (Figure 22). Tennessee has a longstanding waiver that allows it to begin cost sharing at 100% FPL. The number of states charging cost sharing varies by income and service.

Premiums and Cost Sharing for Parents and Other Adults

Most states do not charge premiums for parents and other adults, but some states charge higher premiums than otherwise allowed under federal rules through waivers. In most states, eligibility levels for parents and other adults are below the levels at which states can charge premiums or cost sharing. However, as of January 2018, five states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana) charged premiums or monthly contributions that are not otherwise allowed under federal rules through waivers.

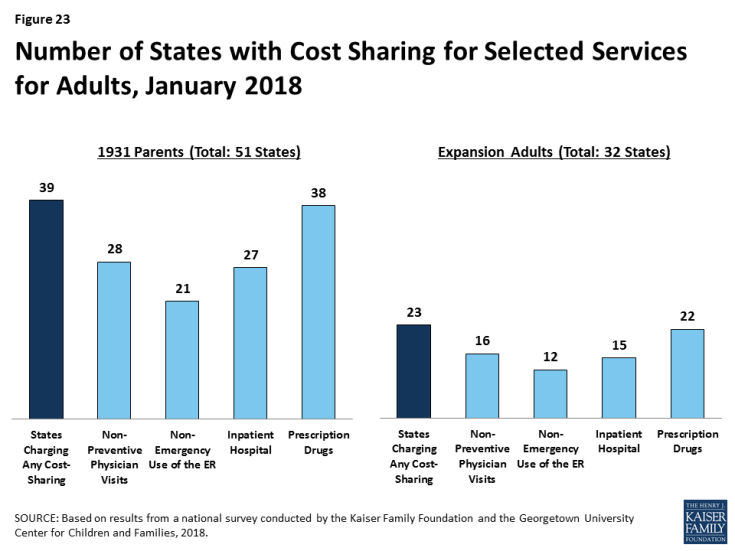

Most states charge cost sharing for parents and other adults in Medicaid. A total of 39 states charge cost sharing for parents and 22 of the 32 Medicaid expansion states charge cost sharing for expansion adults (Figure 23). Most cost sharing amounts remain nominal consistent with federal law. Indiana had received waiver approval to charge a higher copayment for non-emergent use of the emergency room, which was in place as of January 2018. However, the state subsequently removed this copayment when it renewed its waiver. As noted below, other states are seeking to charge higher copayments through waivers.